|

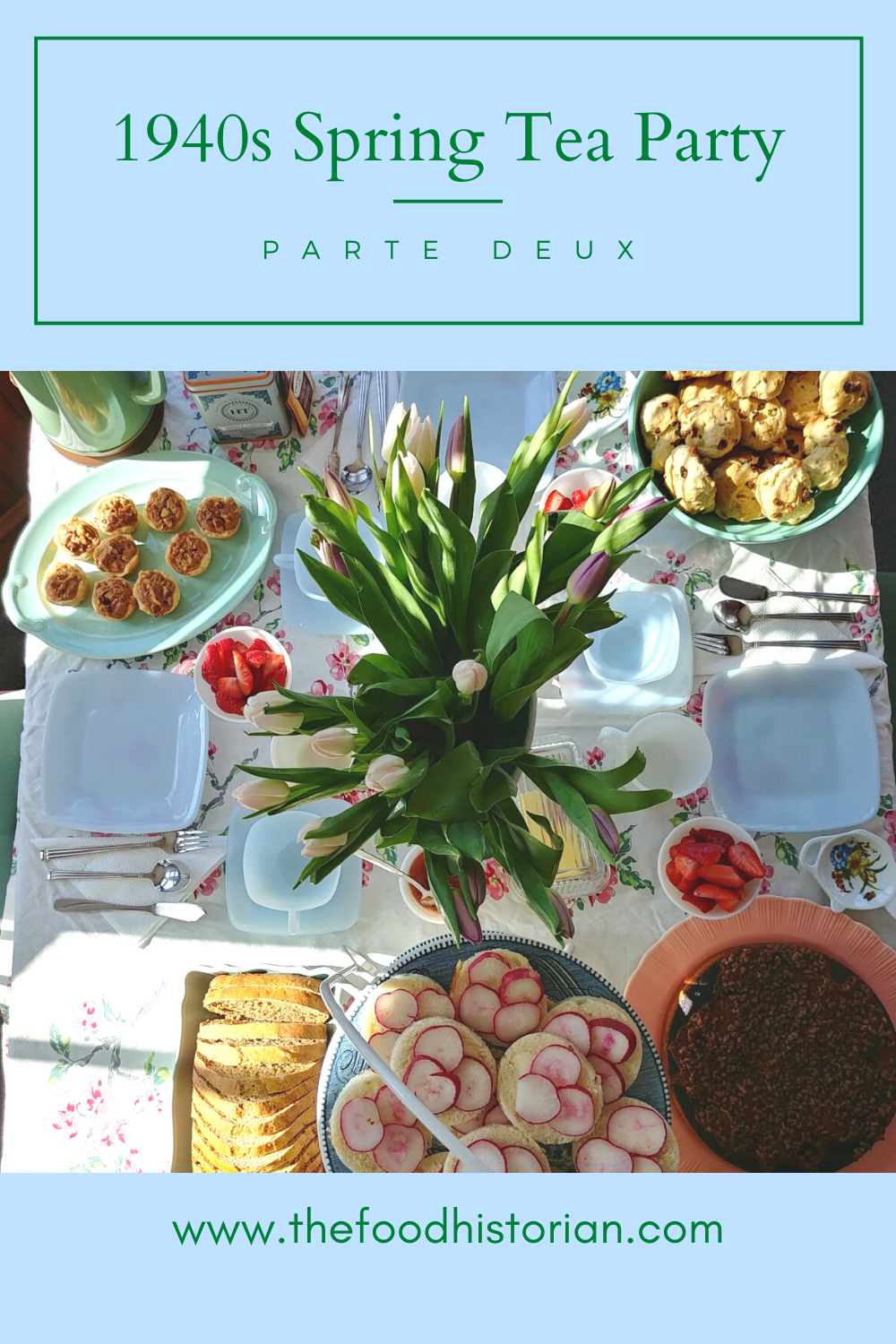

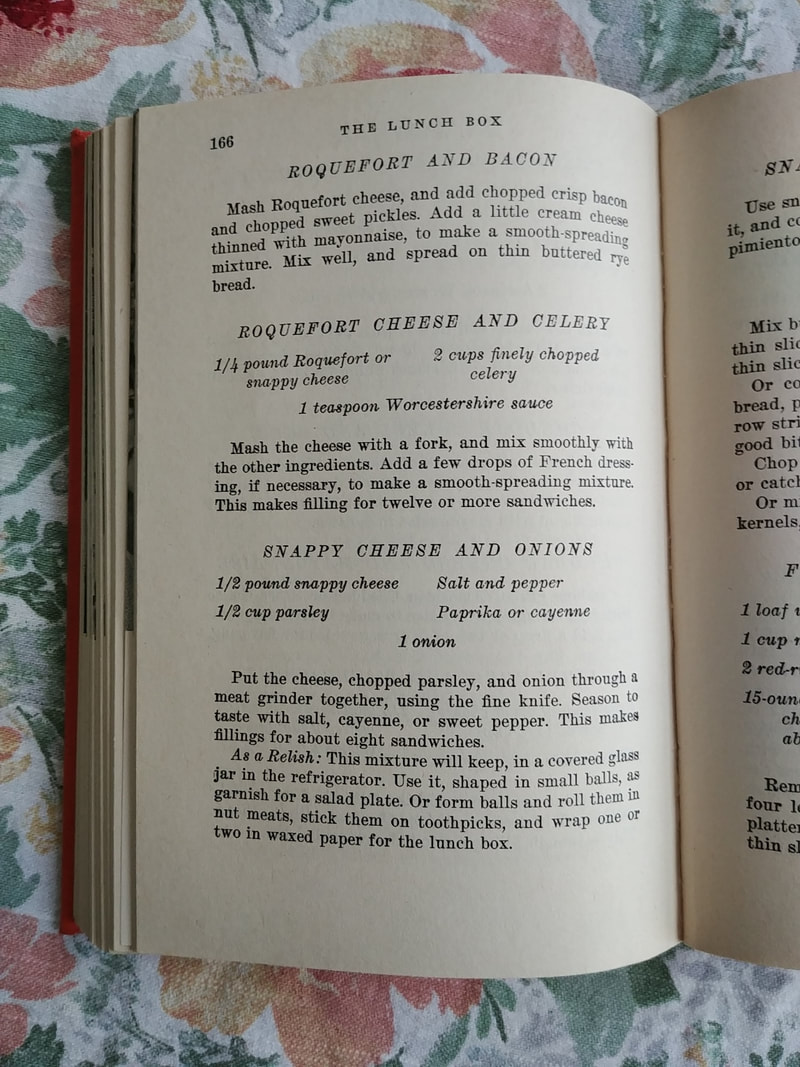

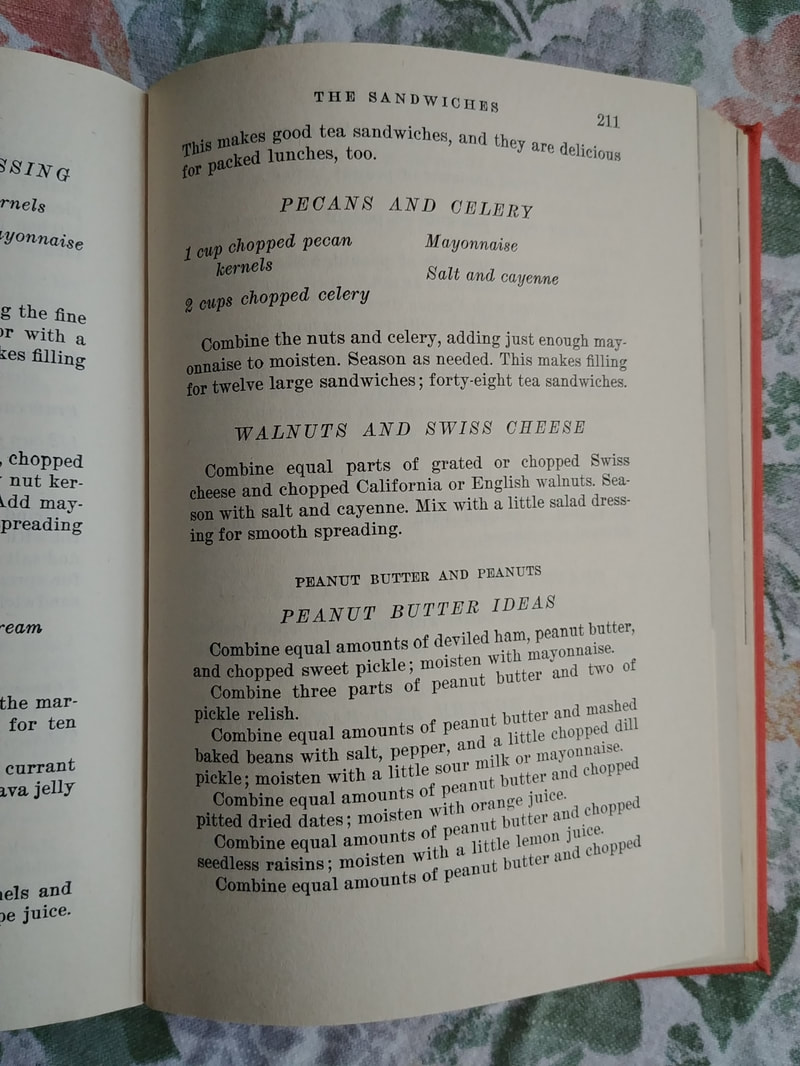

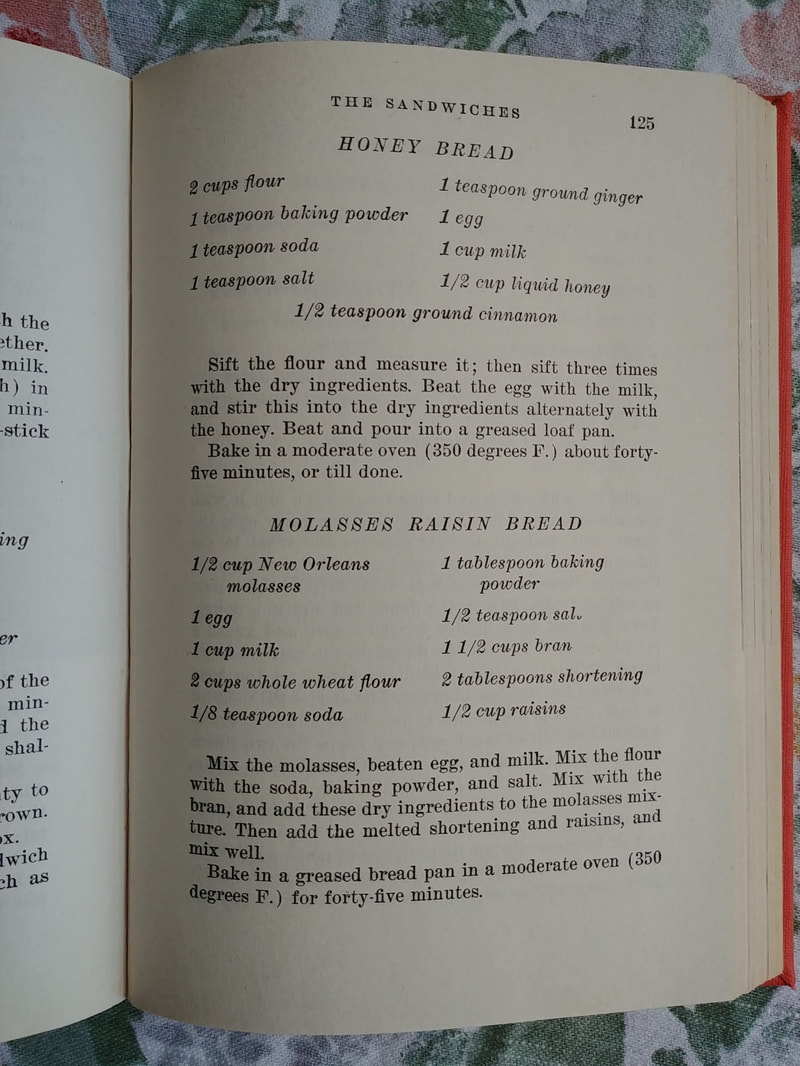

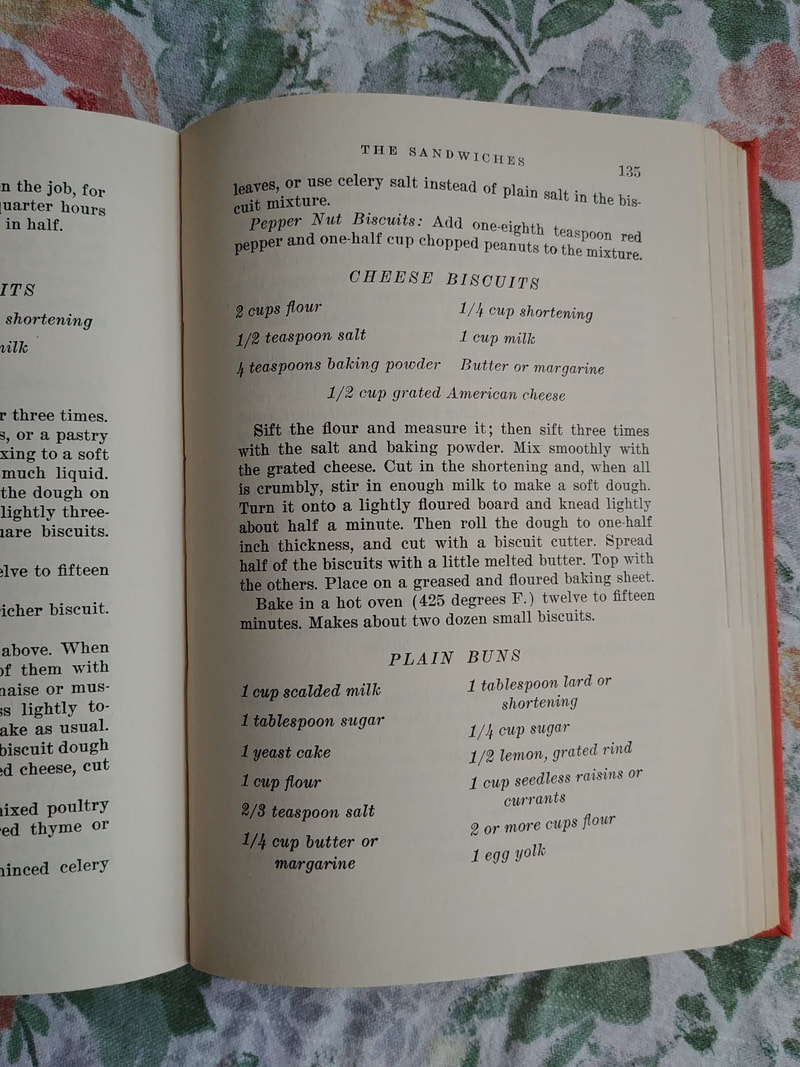

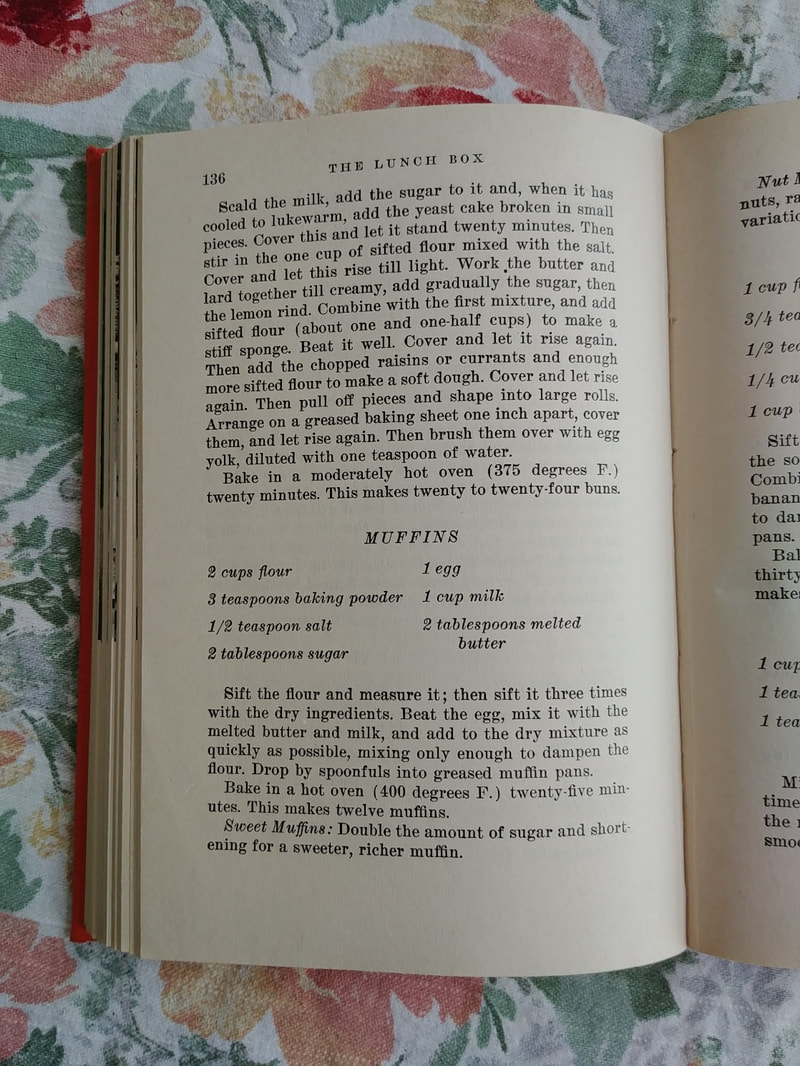

Spring has sprung, with daffodils nodding in the frosty air and trees starting to bud out. So it seemed apt to celebrate with another tea party! Once again, our tiny tea party with just one friend featured all-vegetarian recipes, since said friend is a vegetarian. And also because chicken salad, while delicious, seems lazy when you're looking for something new and interesting to try. This one featured recipes from a new cookbook acquisition, The Lunch Box and Every Kind of Sandwich by Florence Brobeck. My edition was published in 1949, although I believe the original was published sometime in the 1930s. It's also a bright orange library binding without the original dust jacket. So no pretty cover to show off this time! Unlike last time, my ambitious list didn't go QUITE as planned. Adapting historic recipes can be like that. 1940s Spring Tea Party MenuOpen-Faced Radish and Butter Sandwiches on White Open-Faced Cucumber and Cream Cheese Sandwiches on Rye Blue Cheese, Pecan, and Celery Sandwiches on Whole Grain 1940s Whole Wheat Honey Quick Loaf 1940s "Plain Buns" with Butter and Jam Fresh Sugared Strawberries Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake Walnut Tassies Hot Cocoa Tea with Cream and Sugar The SandwichesRadish and butter sandwiches just scream spring to me, and they're very easy to put together. To make things extra fancy, cut sliced bakery bread (not the squishy kind from the bread aisle - hit the bakery and get peasant, sourdough, brioche, or in a pinch, French or Italian bread) with a cookie or biscuit cutter into rounds. Spread with soft butter, top with thinly sliced radishes, and a sprinkling of salt (I used pink Himalayan). The salt is what makes the radishes look wet, but adds a nice flavor. Open-faced cucumber sandwiches are equally easy. Make a cream cheese spread with softened cream cheese (15 seconds in the microwave does the trick), and thinly sliced scallions and dried dill. You can use jarred garlic or minced sweet onion instead of scallions. Spread it on any kind of rye bread. Top with English (a.k.a. seedless - even though they're not - or burpless) cucumbers. If you're hungry, top with another slice of bread spread with the cream cheese mixture, otherwise serve open-faced (which is prettier and more Scandinavian). If you're going really fancy, use fresh dill in the cream cheese and top each sandwich with a sprig of fresh dill. The little square sandwiches were a mashup of two recipes from the The Lunch Box - "Roquefort Cheese and Celery" and "Pecan and Celery" fillings. I decided to mash them up - literally - into one, slightly more interesting filling. I mixed a quarter pound of very soft blue cheese with about a cup each of diced pecans and finely minced celery, with a splash of Worcestershire sauce. It was a curious mixture. Next time I would probably add cream cheese to temper the blue cheese a little, and maybe add some scallions and/or smoked paprika. But otherwise it was quite nice on squares of thinly sliced whole grain bakery bread. Half the fun of tea sandwiches is the fun and dainty shapes you create. I always find it easier to slice the bread first, and then fill, but some people do it the other way around. Whole Wheat Honey Quick LoafWhen one encounters a recipe entitled "Honey Bread," one expects it to taste of, well, honey. Instead, the spicing of this little quick bread leaves the impression of gingerbread more than honey. Curiously, the recipe also contains no fat. I was skeptical, but aside from an accidental overbaking (which I think dried it out), it turned out fairly decently, if scarcely tasting of honey. I followed this recipe pretty much to the letter. It makes a tall loaf with a springy crumb - not at all the crumbly, moist, cake-like texture we come to associate with most quick breads today. Much more like true bread texture than cake. Here's the original recipe: 2 cups flour (I used white whole wheat) 1 teaspoon baking powder 1 teaspoon soda 1 teaspoon salt 1 teaspoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon 1 egg 1 cup milk 1/2 cup liquid honey Sift the flour and measure it; then sift three times with the dry ingredients (or if you're lazy, just whisk everything together). Beat the egg with the milk, and stir this into the dry ingredients alternately with the honey. Beat and pour into a greased loaf pan. Bake in a moderate oven (350 degrees F.) about forty-five minutes or until done. Tip out of the pan and cool on a rack. Serve with salted butter, honey butter, and/or jam. 1940s "Plain Buns"This recipe is deceptive. The title, "Plain Buns" is not accurate - flavored with lemon zest and currants (I used golden raisins), the flavor was surprisingly strong and delicious. Designed to be used with cake yeast, all I had was rapid rise yeast, so I think they got a little overproofed. I'm going to try making them with active dry yeast again, so I won't comment too much on what I did, and just give you the original recipe: 1 cup scalded milk 1 tablespoon sugar 1 yeast cake 1 cup flour 2/3 teaspoon salt 1/4 cup butter or margarine 1 tablespoon lard or shortening 1/4 cup sugar 1/2 lemon, grated rind 1 cup seedless raisins or currants (I used golden raisins) 2 or more cups flour 1 egg yolk Scald the milk, add the sugar to it and, when it has cooled to lukewarm, add the yeast cake broken into small pieces. Cover this and let it stand twenty minutes. Then stir in one cup of sifted flour mixed with the salt. Cover and let this rise until light. Work the butter and lard together until creamy, add gradually the sugar, then the lemon rind. Combine with the first mixture, add the sifted flour (about one and one-half cups) to make a stiff sponge. Beat it well. Cover and let it rise again. Then add chopped raisins or currants and enough more sifted flour to make a soft dough. Cover and let rise again. Then pull off pieces and shape into large rolls. Arrange on a greased baking sheet one inch apart, cover them, and let rise again. Then brush them over with egg yolk, diluted with one teaspoon of water. Bake in a moderately hot oven (375 degrees F.) twenty minutes. This makes twenty to twenty-four buns. Obviously I didn't let rapid rise yeast go through fours separate rises! But I think it still overproofed a bit. I also forgot the egg wash! Which meant the buns looked a bit more like rocks. But they sure tasted good, and that's what mattered. If you enjoy the citrusy flavor of hot crossed buns, you'll love these. Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake & Walnut TassiesI've made Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake before, but this time I was somehow out of coconut, so I used chopped pecans for the topping as chopped nuts are the other traditional topping ingredient. Not QUITE as good as the coconut, but still yummy. Sadly for you, I did not make the walnut tassies (my friend did), and thus cannot share the recipe. However, she, like I did, had to make some substitutions! For Walnut Tassies are supposed to be Pecan Tassies, but my friend was out of pecans, so walnuts it was. The original recipe is supposed to be like tiny pecan pies, but tiny walnut pies were equally good. One of the primary joys of tea parties, of course, is in the dishes. I've got my vintage Fire King Azurite Charm teacups and saucers, with newly acquired luncheon plates, some milk glass compotes with sugared strawberries in them, milk glass D ring mugs for cocoa, and assortment of vintage servingware in springy shades, on a vintage floral tablecloth. With tulips in the middle, of course. If you missed the last spring tea party, you can check it out here, with a promise of more to come! Have you had a tea party recently? What favorite food did you feature? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

1 Comment

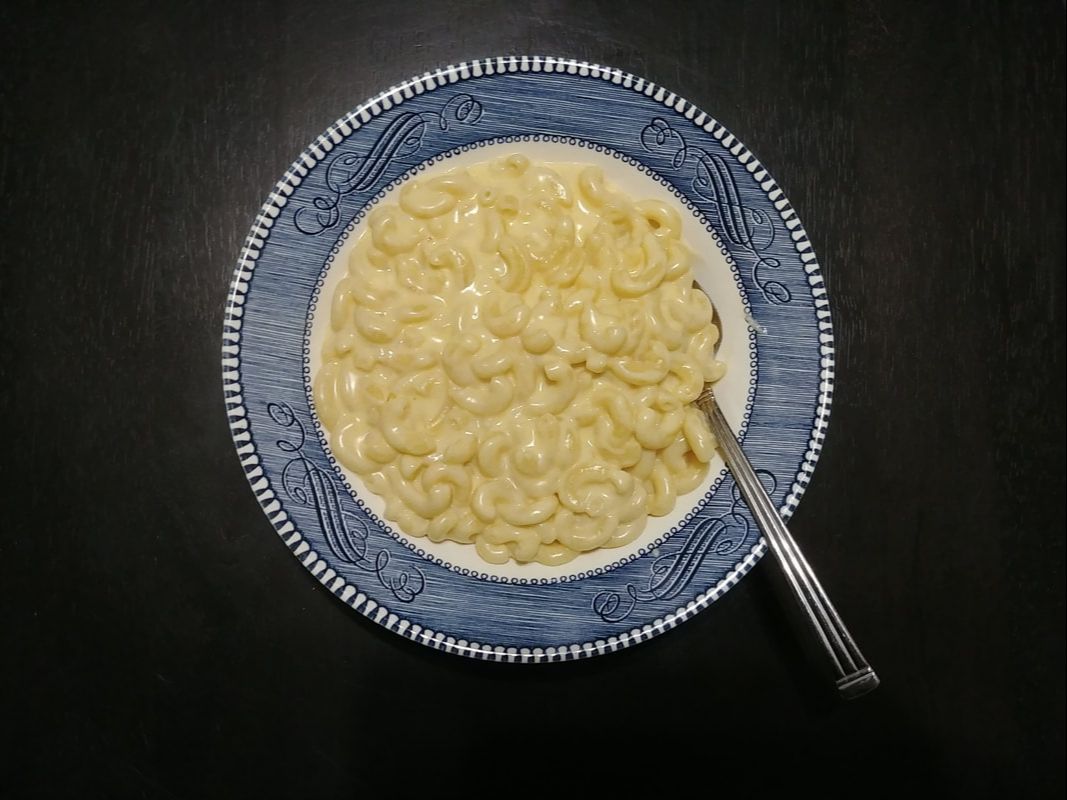

I've given a couple of talks on the history of macaroni and cheese now, and invariably someone brings up how homemade macaroni and cheese is so much better than Kraft. And I agree! While Kraft Dinner, invented in 1937, is definitely an important part of American history, you don't have to like it to appreciate it.

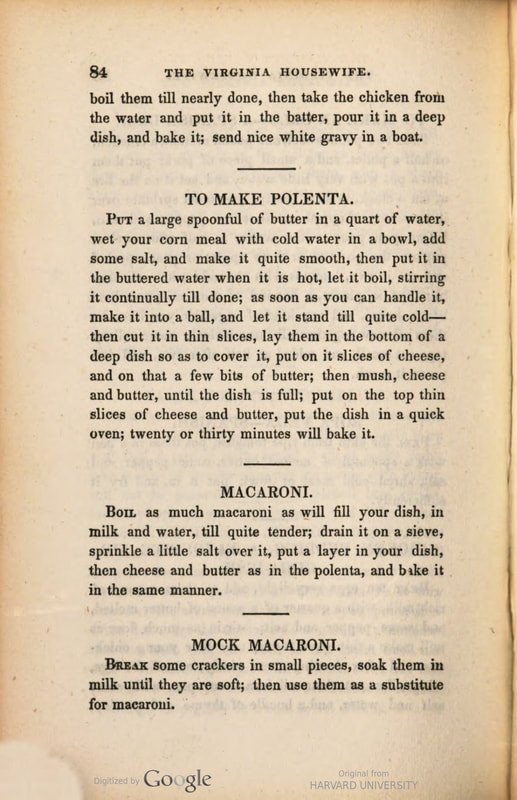

Macaroni and cheese dates back quite far in Western history. I think macaroni and cheese has its origins in ancient Roman shepherding and cacio e pepe - dried pasta, a little pasta water, very finely grated (fluffy!) pecorino romano cheese, and plenty of black pepper. But I like lots of black pepper on my macaroni and cheese, so perhaps I'm biased. By the 18th century, it's popular in Europe and James Hemings, enslaved chef to Thomas Jefferson, famously brings it back from his time in France. In fact, his recipe may have influenced cookbook author Mary Randolph, who was related to Jefferson, and whose macaroni and cheese recipe is one of the first to appear in an American cookbook. Macaroni and cheese is not particularly difficult to make. You can go super old-school and just layer butter and cheese, like Mary Randolph in The Virginia Housewife, one of the earliest references to macaroni and cheese in American cookbooks.

Or, you could emulate the later 19th century with a mornay sauce - that's bechamel maigre with some shredded cheese mixed in.

I'm firmly in the cheese sauce category, although I'm tempted to try the butter-and-cheese baked version, just to see how it measures up. Regardless, over the course of the 19th century, macaroni and cheese underwent a bit of a revolution, from expensive imported dish of the wealthy, to affordable railroad dining car, hotel, and cafeteria staple. For some, notably Black Americans, it also became an essential part of Thanksgiving and holiday tables - with recipes as varied as the cooks who made them. By the time we got halfway through the 20th century, it had also become a Depression-proof comfort food, beloved by children and people of all ages. Whether you're weathering a global pandemic, a bad day at work (or school), or just want to relive your childhood a bit, it's hard to go wrong with a steaming hot bowl of creamy, comforting, delicious macaroni and cheese. Better Than Kraft Macaroni & Cheese Recipe

There's not a lot of measuring in my kitchen, but the butter-to-flour ratio must always hold true - equal parts. You can increase or decrease the cheese to your preference, you can even mix cheeses. If you want something that tastes vaguely like Kraft, be sure to go with plenty of mild cheddar. Otherwise any kind of cheese, from smoked gouda to swiss to blue to cream cheese, are all fair game. You can halve this recipe if need be, but just make the whole pound of pasta. It makes decent leftovers. Here's what you'll need.

1 pound semolina pasta, any kind (I like elbows or medium shells) 1/2 cup butter (1 stick, salted or unsalted) 1/2 cup white flour at least 1 quart whole milk, maybe more 1-2 cups shredded cheese 1 tablespoon Dijon mustard (secret ingredient, optional) 1-2 teaspoons salt Your equipment needs are also basic. You'll need a 4 or 5 quart stockpot to boil the pasta, and a 2 quart pot to make the sauce, preferably one with a heavy bottom. Oh, and life will be a lot easier if you have one of these:

Okay, on to the instructions. First, grate your cheese. Don't use the pre-packaged store-bought shredded cheese - it's got anti-clumping agents (usually cellulose) that also prevent it from melting well.

Then, fill your 4 or 5 quart stockpot with at least 3 quarts of water and bring to a boil over high heat. Once boiling, add the pasta, a tablespoon of salt, give it a good stir to make sure it doesn't stick, and let it come back to a boil. Next, add your butter to the smaller saucepan and cook over medium heat until the butter is melted and bubbling. When the butter makes a sizzling noise, quickly whisk in the flour, making sure there are no lumps. And then, the important part, let the butter and flour mixture cook for at least 30 seconds, stirring occasionally. If you don't cook your flour, your sauce will be pasty. Yuck. There's a fine balance between golden cooked mixture and browned roux, though, so just keep an eye on it. Once your roux is cooked, start adding whole milk, a cup or so at a time. Whisk and allow to thicken between additions. After you've added a few cups of milk and the sauce is thickening up again, add your shredded cheese and Dijon mustard, and whisk thoroughly until the cheese is melted into the now very thick sauce. Then add more milk and whisk vigorously again. Keep adding milk until your saucepan is at least 2/3 if not 3/4 full. Meanwhile, your pasta has been boiling. You should check it occasionally to test doneness - the pasta should be soft but not soggy. Taste a piece each time. When done, drain and return to the cooking pot. Once your cheese sauce is thickened up enough to nicely coat a spoon, taste for salt and add, 1 teaspoon at a time. You want your sauce to be quite salty, as the pasta will be bland and absorb flavor. Once you're satisfied (always better to undersalt - you can add more at the table), pour the cheese sauce into the stockpot with the pasta and stir well. If the sauce seems a little liquidy, let it rest on the pasta for a few minutes. The pasta will absorb much of the liquid and thicken the sauce. Serve hot with extra salt for those who like it very salty (like me), and plenty of black pepper. Feel free to also top it with more cheese, chopped tomatoes, sliced scallions, caramelized onions, crumbled bacon, sausage, steamed broccoli, or anything else that strikes your fancy.

If making the cheese sauce and boiling the pasta at the same time seems tricksy and too much multi-tasking, boil and drain your pasta first, and then make the sauce. You'll feel better if you can give it your full attention, without getting distracted.

And there you have it - a macaroni and cheese recipe that is tastier than Kraft, nearly the same speed (start to finish is about 30 minutes), and almost as cheap. Do you have a favorite way you like your macaroni and cheese?

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

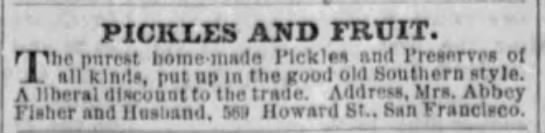

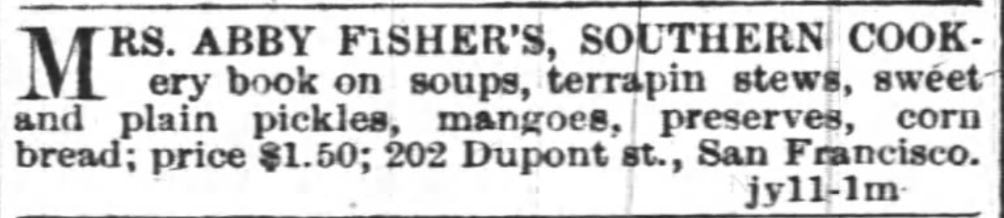

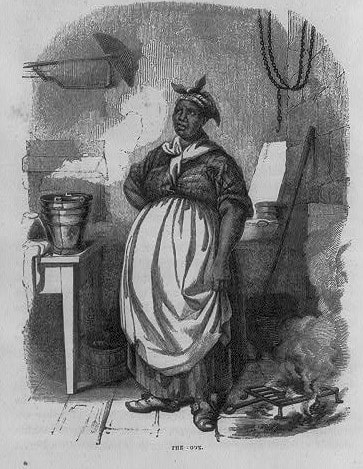

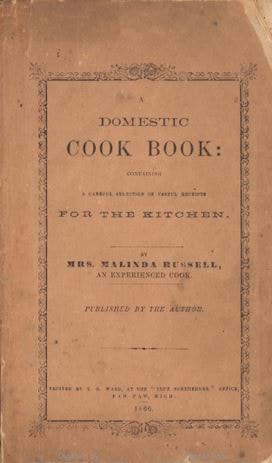

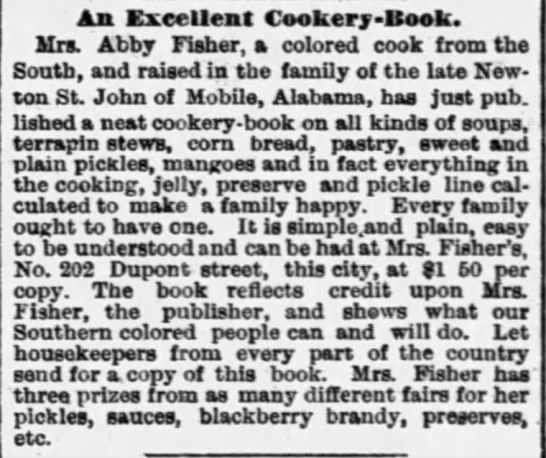

Throughout the 19th century, white women used their domestic assets to pick up the slack left by disabled or deceased husbands - homes became boarding houses and tea rooms and domestic skills were translated into magazine articles and cookbooks. But free Black women in the 19th century did not have as many assets. And even when they did, these assets were often taken from them, and a racist and sexist judicial system gave them little recourse to recover property. Enslaved women freed by the Emancipation Proclamation had their freedom, but little else. The promised 40 acres and a mule never materialized. Despite these often difficult starts, many free and formerly enslaved women of color used their wits and skills to make their own way in the world. Often relegated to service jobs in households, many women created their own small businesses to avoid working for wages - tea rooms, boarding houses, laundries, seamstress and millinery shops, catering, etc. Most of these jobs had low startup costs and could be done from home, allowing for the care of children and family members. Many women also worked as professional cooks for taverns and hotels, a job that held more promise of profit and respect than working in a private household. The vast majority of women working in these fields remain hidden from history - unnamed and un-written-about. But some women of color have managed to make their mark on food history. Here are a few of their stories. Anne Northup - Twelve Years AloneAnne Northup was my first real encounter with the stories of adversity and perseverance many Black women faced throughout the 19th century. I attended a special program at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City with a historic dinner recreated by The Food Griot - Tonya Hopkins. Anne Hampton was born in 1808 in upstate New York. A free woman of color, she married Solomon Northup in the 1820s and in 1834 they sold their farm and moved to Saratoga. Solomon often worked as a fiddler and Anne worked as a cook and kitchen manager at hotels in the spa resort town. She was working at the Pavilion Hotel in Saratoga when she met wealthy white New Yorker Eliza Jumel in 1841. Divorcee/widow of Aaron Burr, Madame Jumel convinced Anne to come south and serve as a cook in her household. Anne sent her eldest daughter Elizabeth to Manhattan with Jumel, but waited until later in the year to come south herself, likely finishing out the busy tourist season. Earlier that summer of 1841, Anne's husband Solomon had answered an advertisement looking for musicians for a job in Virginia. An accomplished violinist, Solomon had answered the advertisement and traveled south. He was captured and sold into slavery, spending the next twelve years enduring brutal conditions on a Louisiana sugar plantation. Anne was left to fend on her own. After a year in Eliza Jumel's household, Anne and some (but not all) of her children returned to Saratoga, where they stayed until 1850, when they moved to Glens Falls and Anne continued her hotel work. They were not reunited with Solomon until 1853. He wrote a book about his experiences - Twelve Years a Slave. We lose track of Solomon Northup in the 1860s and his death date is unknown, although Anne and her children continue to live in New York. To learn more about the Northup family, read this excellent account by historian David Fiske. Anne Northup died on August 8, 1876 in Moreau, New York. Although she leaves behind no documentation of the food she cooked, given her positions in fashionable resort town hotels and wealthy households, she was likely very skilled in a variety of foodways. To me, she represents how many free women of color made their way in the world on the strength of their cooking skills, even in the face of extraordinary adversity. Malinda Russell & Her Union PrinciplesIn 2000, Jan Longone ran across a slim, crumbling cookbook wrapped in brown paper at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where she is curator of American culinary history. That cookbook, A Domestic Cookbook, published in 1866 by a woman named Malinda Russell, turned out to be the earliest known cookbook published by an African American woman. The cookbook has since been digitized, and when I read it for the first time the other day, I was struck by the incredible hardship Russell had to overcome in her life. In the autobiographical account that explains why she wrote the cookbook, Russell recounted the many setbacks in her life. Born free in Tennessee, at age 19 she set out to emigrate to Liberia, a promise of life free from the racism and oppression that continued to plague free Black communities in the North. But along the way, she was robbed by someone from her party, and was forced to stay in Virginia, where she made a living as a cook and a nurse. There, she married Anderson Vaughn, and they had a son together, but Vaughn died just four years later, leaving Russell a widow with a handicapped son. She moved back to Tennessee and opened a boarding house in a town that featured springs as a tourist attraction. She later opened a pastry shop in that same down and had saved up a sum of money to support herself and her son. But in early 1864, she was attacked and robbed by a "guerrilla party," likely Confederate soldiers. She and her son fled Tennessee during the height of the Civil War. Although Tennessee was a Union state, its proximity to the border meant it was not safe for Russell. She made her way to Michigan, enduring several attacks along the way, and went on to start over, again, in a new state. In May, 1866, she published A Domestic Cookbook. She closed her introduction stating that she hoped the sale of the cookbook would help her raise funds to return to Tennessee and reclaim some of her lost property when peace was restored. We do not know if she ever made it home to Tennessee, or really much else about her at all, although Jan Longone has worked to find more about her. According to Russell herself, "I have learned my trade of Fanny Steward, a colored cook, of Virginia, and have since learned many new things in cooking." She also indicated her cookbook was organized along the lines of Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife (1824). Malinda Russell reset much of the conventional wisdom about Black cooking heritage at the time it was rediscovered. But her cookbook is not much different from any other cookbook of the period - reflecting her experience as a boarding house owner and cook, cooking for the public and likely for audiences diverse in race and socioeconomic status. It also knows its audience, consisting largely of dessert and preserves recipes. These were commonly featured in published cookbooks because they were more complex than the everyday cooking of meat and vegetables and less likely to be familiar to ordinary cooks. Her cookbook contains everything from the humble "Baked Indian Meal Pudding" and 'Sliced Sweet Potato Pie," to the exquisite "Floating Islands" and "Charlotte Russe." For me, the most striking thing about Russell is not the content of her cookbook, but rather the fact that it exists at all - a testament to her difficult life and the grit she used to persevere. What Abby Fisher Knew "Pickles and Fruit. The purest home-made Pickles and Preserves of all kinds, put up in the good old Southern style. A liberal discount to the trade. Address, Mrs. Abbey Fisher and Husband, 569 Howard St. San Francisco." Advertisement from the December 13, 1879 issue of "The Placer Herald," published in Rocklin, CA. Unlike Anne Northup and Malinda Russell, Abby Clifton was born into slavery in 1831 in South Carolina to a white father and an enslaved mother. It is unclear when gained her freedom, but by 1860 she had moved to Alabama and married Albert Fisher. In 1877, they emigrated to California and by 1880, Abby and Albert were in San Francisco, where the 1880 Census listed Abby as a "cook" and Albert as a pickle and preserve manufacturer. But this attribution was likely due to sexism common among census takers. In reality, it was Abby who was manufacturing pickles and preserves - as listed in an 1882 San Francisco directory. Albert was listed as a porter. Abby leveraged her expertise in pickles and preserves to reach the highest echelons of San Francisco society. She was awarded a diploma at 1879 Sacramento State Fair. At the 1880 San Francisco Mechanics Institute Fair, she won a bronze medal for her pickles and preserves. Although she and Albert could not read or write, in 1881 she published the cookbook, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. with assistance from white friends who helped her translate and transcribe her memorized recipes into cookbook format. The book does not contain just pickles and preserves, although they and her famous blackberry cordial certainly make a showing. The title inclusion of "Old Southern Cooking" is certainly apt, given recipes for "Maryland Beat Biscuit," "Plantation Corn Bread," "Ochra Gumbo," "Creole Chow Chow," "Sweet Potato Pie," and "Peach Cobbler." But it also includes typical British-American foods popular in the Northeast and throughout the United States, including "Sally Lund" bread, "Jumble" cookies, "Sauce for Suet Pudding," "Rhubarb Pie," (rhubarb grows poorly in the South, needing below freezing temperatures), three different kinds of "Sherbet," "Yorkshire Pudding," and "Terrapin Soup." In short, her cooking is more representative of broad American style cooking of the period, with some Southern flavor, rather than stereotypically "Southern" (i.e. Black) cooking. The interest in Southern cooking, as evidenced by the marketing of her book, was likely part of a reaction to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Historian Megan Elias has written about "Lost Cause cookbooks" in which white Americans romanticized the "good old days" of slavery and subservient Black folks with "magic" cooking skills. It is possible that Abby Fisher's cookbook was swept up in the wave of racist nostalgia. But it is also possible that Abby's cookbook was simply a reflection of the interest in California residents in the cuisines of many newly arrived emigrants of all cultures and backgrounds. This seems to be the case in one announcement, published in the San Francisco Examiner on July 11, 1881. It reads: "An Excellent Cookery-Book. "Mrs. Abby Fisher, a colored cook from the south, and raised in the family of the late Newton St. John of Mobile, Alabamaa, has just published a neat cookery-book on all kinds of soups, terrapin stews, corn bread, pastry, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes and in fact everything in the cooking, jelly, preserve and pickle line calculated to make a family happy. Every family ought to have one. It is simple and plain, easy to be understood and can be had at Mrs. Fisher's, No. 202 Dupont street, this city, at $1.50 per copy. The book reflects credit upon Mrs. Fisher, the publisher, and shows what our Southern colored people can and will do. Let housekeepers from every part of the country send for a copy of this book. Mrs. Fisher has three prizes from as many different fairs for her pickles, sauces, blackberry brandy, preserves, etc." Although we may never know how many copies Abby sold, the cookbook seemed to garner positive reviews. For several weeks in 1881, she (or the publisher) advertised it in the Oakland Tribune (see below).  "Mrs. Abby Fisher's, Southern Cookery book on soups, terrapin stews, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes, preserves, corn bread; price $1.50; 202 Dupont st., San Francisco. jy11-1m." Advertisement for Mrs. Fisher's cookbook in the "Oakland Tribune," published July 11, 1881, but running for several weeks prior and after. In the 1890 San Francisco directory, "Mrs. Abbie Fisher" was still listed as "mnfr. pickles and preserves," but it is unclear what happened after that. Her exact death date is also unknown. No known obituary was published. After the Great San Francisco Fire of 1907, reference to Abby and her cookbook all but disappeared until a copy surfaced in 1984 at a Sotheby's auction in New York City. The Schlesinger Library purchased it and at the time it was thought to be the first cookbook published in the United States by a Black woman, until Malinda Russell toppled Abby from her throne in 2000. Like Malinda and Anne, Abby used her cooking skills to make her own way in the world - supporting her family and showcasing her talents. Ghosts in the KitchenOf course, we know about these women because they left a written record. We know about Anne through her husband Solomon and his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave and the records of Eliza Jumel. We know about Malinda because of her cookbook and the autobiography she includes in it. And we know about Abby because of her cookbook and her existence in newspapers and city directories. But there were tens of thousands of women of color making their own way on the strength of their culinary skills, just like these women, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Ashbell McElveen called James Hemings the "ghost in America's kitchen," but he wasn't the only one. Enslaved women and men shaped American food profoundly. And women of color - enslaved, freed, and born free - left their mark as well. Because I know how history works, I am hopeful that more records and cookbooks of cooks of color - published or not - will continue to show up in the coming decades. And when they do, I know they'll help us better understand how our food got to be the way it is, and where it can go in the future. Further ReadingAnne Northup:

Malinda Russell:

Abby Fisher:

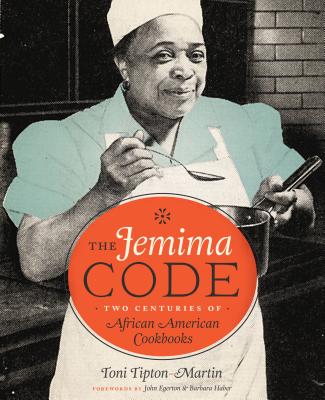

The Jemima CodeThe Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, Toni Tipton Martin. University of Texas Press, 2015. ISBN 0292745486. This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. If you want to know more about African American cookbooks, I recommend Toni Tipton Martin's The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. Although the information for each entry is sadly quite brief, it is nonetheless an important, enlightening, and beautifully produced catalog of all the known cookbooks authored by African Americans (real and fictional) in the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed