|

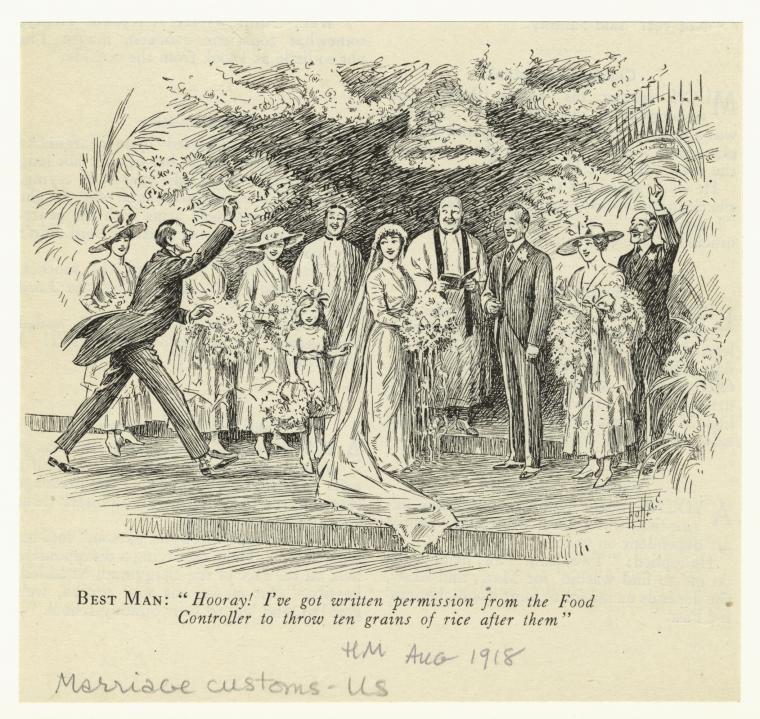

I ran across this little political cartoon when researching for my book Preserve or Perish, which is about food in New York during the First World War. I also study wedding food traditions, so of course when I saw this, I cracked up.

A wedding party is gathered at the altar, and everyone is turning to look at the best man, who is rushing up to the altar waving a piece of paper. The caption reads, "BEST MAN: 'Hooray! I've got written permission from the Food Controller to throw ten grains of rice after them.'" Although the New York Public Library doesn't list what newspaper or magazine it is from, it is dated as August, 1918. The cartoon is hilarious for a number of reasons, but the primary one is that it is a gross exaggeration of the level of food control in the United States during the First World War. With the exception of sugar toward the end of the war, mandatory rationing was never put into place for ordinary Americans. Only food producers and retailers had restrictions placed on them. On potential exemption from that (besides sugar) was the requirement that all customers had to buy two units of non-wheat grains or flours for every one unit of wheat they purchased. For example, by purchasing one pound white wheat flour, a shopper would be required to purchase an additional two pounds of some other grain (they could mix and match) such as cornmeal, rye flour, barley flour, rice, or oatmeal. Rice, however, was never rationed. In fact, although it was not as widely available as cornmeal, it was touted as a wheat substitute. But political cartoons are all about taking things to extremes, so the joke is that food is so heavily "controlled" that even a few grains of rice must have permission to be thrown away. Which also fits into the propaganda around wasting food that was prevalent at the time. The other interesting, although not particularly hilarious, commentary of this cartoon is that this is clearly a fairly wealthy family. Then men are wearing morning coats with tails and spats on their shoes. The bridesmaids are in matching outfits. The bride has a very long veil and there are flowers and greenery galore. It indicates that even the wealthiest Americans could not escape the reach of the "Food Controller" - a.k.a. Herbert Hoover, Federal Food Administrator (a term he vastly preferred to "controller" or even the popular-in-the-press "dictator," which did not have quite the same meaning then as it does now). The early 20th century was when marriage traditions were starting to solidify as weddings became more formal, public affairs. Throwing rice at the couple at the end of the wedding was one of those "traditions" at this point. Along with a white dress, flower bouquet, white bride's cake to eat at the breakfast (yeah, they were still breakfasts at this point, although luncheons and teas were becoming more common) and spice/fruitcake groom's cake to take some as a favor. In all, it's a cute-but-biting commentary on food control during the First World War. And it made me laugh, so I had to share. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more!

0 Comments

"Henry Browne, Farmer" - film produced in 1942 by the United States Department of Agriculture, digitized by the Prelinger Archive of archive.org.

Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1943, "Henry Browne, Farmer" was a propaganda film produced by the United States Department of Agriculture in 1942. It is also one of the few major propaganda pieces (there were many thousand smaller efforts) directed specifically at African Americans.

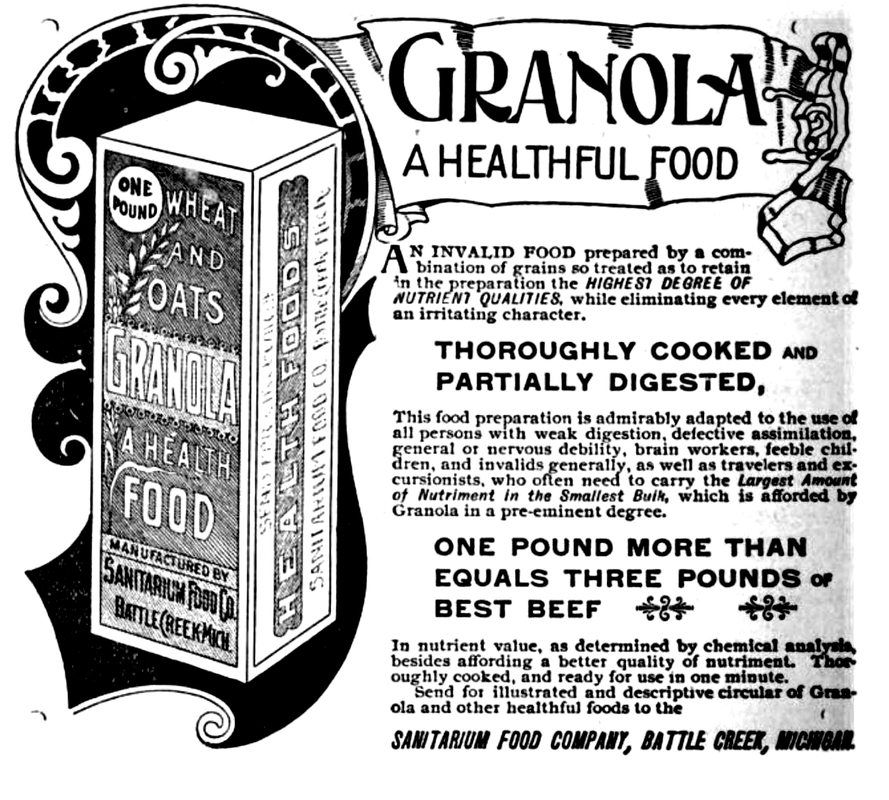

In it are many hallmarks of post-Reconstruction life for African Americans in a white supremacist country. References to using only mules instead of a tractor. Eating cornbread and fatback last year, but having a cow and chickens, meaning milk and eggs for breakfast this year. Specific programs are not mentioned, but it is clear that by cooperating with the federal government to grow peanuts, that the Browne family is also participating in other endeavors, like raising chickens and keeping a victory garden. Children, in particular, were encouraged in rural areas to raise chickens (like "sister" in the film), dairy cows ("brother's job), and help with Victory gardening and around the farm. Similar programs around pig clubs and tomato canning clubs were in use during World War I as well. The film, which sadly does not record any of their voices (just the voiceover), ends with the family going to visit their oldest son, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen. This is both a call to service for all Americans and "proof" that the family is just as patriotic as any white American. This film was groundbreaking in that it put African American farmers on equal footing with other Americans joining the war effort. It emphasized Henry Browne's good agricultural techniques, like saving burlap bags instead of throwing them away, and greasing and covering farm equipment, which meant that it was likely to "last the duration" in a time when steel was in short supply and new farm equipment was likely to be expensive or impossible to get. It also did not have too many hallmarks of racism, which is surprising for the time. Unlike during the First World War, the United States propaganda machine during WWII was broadening the definition of who "counted" as an American, to give a little more credence to the idea that Americans were fighting to preserve democracy and freedom abroad. Unfortunately, the message was ultimately still hypocritical as many Black people in the south were being terrorized by Jim Crow laws, police, incarceration, and the Ku Klux Klan. However, a Civil Rights movement, which had been borne out of the returning Black soldiers of World War I and which broadened during World War II, was underway, as African Americans sought to free themselves from terror, discrimination, and disenfranchisement. World War II would mark the end of an era for many Black farmers in the rural south. Industrial work in northern and coastal cities, long a draw for those escaping sharecropping and other slave-like conditions in the South, became a bigger draw during the total war mobilization of the nation's industries. Thanks to protests from African American unions like the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the NAACP, Franklin D. Roosevelt was forced to create the Fair Employment Practices Committee in 1941, which banned discriminatory hiring in federal agencies and for companies employed in defense work, which for the first time allowed many African Americans to receive fair wages and work conditions for the first time. In addition to this draw off of the farms, there is evidence that the USDA engaged in discriminatory practices which helped drive African American farmers off of their land and caused nearly 90% of black farmers to lose their land in the years following World War II. Pete Daniel's book Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights explores this topic in more detail, and in fact, until very recently, the USDA continued their discriminatory practices. In all, "Henry Browne, Farmer" is one of the better propaganda films to come out of the Second World War. With quiet assurance and emphasis on the important work of ordinary Americans to do their part, it lacks the overly patronizing tone and bombast of other "documentaries" from the period. It's one of my favorites, and I hope you enjoy it as well. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! "The Food That Built America" just finished up last night, and I also reached over 200 likes on Facebook! So as a reward to my new friends and faithful followers, I thought I'd take a look at the Kellogg Brothers, who show up in all three episodes. Granola was the cereal that started it all. In the late 1870s, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg used it as part of his health regimen for his sanitarium patients. Based on a twice-baked unleavened bread made of wheat and oat flour, the cereal was then hammered into chunks and soaked in milk before serving. He initially called it "Granula." There was just one problem - there already was a "Granula." This was not covered in the History Channel series, but Kellogg was actually threatened with a lawsuit in 1881 by James Caleb Jackson, of upstate New York. Like Kellogg, Jackson was influenced by Seventh Day Adventist Ellen G. White, who advocated for vegetarianism and other health reforms. But at his hygenic water cure spa in upstate New York, Jackson developed "Granula," based on a twice-baked plain graham flour biscuit (graham flour is un-separated ground whole wheat). He rolled the flour-and-water mixture into sheets, which were baked, then broken into pieces and baked again, and then broken into smaller pieces, similar to the Grape-Nuts that C.W. Post would eventually develop. He invented "Granula" in 1863 - fifteen years before Kellogg. In response to the threat of lawsuit, Kellogg simply changed the name to "Granola." Both Jackson and Kellogg were likely inspired by simple rusks or zwieback or even hardtack. Dating back to ancient times, twice-baked breads were shelf-stable, durable, and long lasting. Hardtack (sometimes called a "cracker" or "ship's biscuit") was a common sight on merchant vessels and naval ships alike and was common soldier fare from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War. Made of just flour, water, and salt, hardtack was, well, hard. It was meant to be softened in coffee, stew, or water before it could be eaten. But its hardness made it the ideal, stable staple for long voyages without refrigeration. Rusks, on the other hand, were more likely to be made with sugar, butter, and eggs and were much closer to our most familiar modern incarnation - biscotti. Some rusks, like zwieback, were even yeast-leavened sweet breads that were twice baked. It stands to reason then, that Kellogg's original "Granola" was a mixture of whole grain wheat flour (graham) and oat flour, mixed with water (no salt or sugar), and twice-baked before crumbling into what would become "cereal." Having made hardtack myself, I can inform you that the trick is in the kneading - as you develop the gluten in the flour it smooths out and becomes easier to work and shape (and roll!). While no known recipe for Kellogg's original "Granola" exists, I did dig up a recipe for "Granula" from the 1906 Inglenook Cookbook, published by the Church of the Brethren, a non-demoninational Christian sect. Apparently hard-baked plain cereals continued their trend of association with religious organizations. You can find more about the Inglenook Cookbook in all its incarnations here. In true, early 20th century style (and like many community-based cookbooks from this time period), the instructions are written in paragraph form. Granula Get good graham flour, take pure spring or soft water, nothing else, and knead to a stiff dough. Roll and mould as for biscuit (not as thick). Bake thoroughly in a hot oven. When well done, or over done, remove and cool, then cut each piece in halves and put back in a warm baker and dry to a crisp, not brown or burnt. A yellow brown will not hurt. Now crush or break in small bits and grind them as you would coffee. You now have one of the best health foods known. It can be served in various ways. Soaked in good, rich milk is the best way to eat it. Some like to add a little sugar, some a little salt (but don't add salt when you bake it, it spoils the flavor). Some eat it with fruit. It makes a nice cold Sunday dish and is always ready. It can be used in puddings and mixed with bread for dressings. We have made and used this hygienic food for 23 years, and know its merits. The biscuits, or graham crackers, warm from the oven, well baked, with crispy crust, make a delightful bread. We have a small hand mill to grind them. If you cannot get good graham flour, if it is too rough with bran, add a little white flour, or sift the coarsest bran out. Graham made of white wheat is best. - Sister Amanda Witmore, McPherson, Kans. While granula and similar incarnations continued to be eaten into the twentieth century, what we know as Granola today is not really a direct descendant of Kellogg's granola (or Jackson's granula). In 1900 a Swiss physician named Dr. Maximillian Bircher-Benner developed another type of grain cereal called Bircher-muesli (later shortened to muesli). Adhering to Bircher-Benner's beliefs that raw foods were the most healthful, muesli primarily contains uncooked rolled oats, with nuts, seeds, and fruits added in. Served plain or with milk, it was originally intended as an accompaniment to meals or a light supper, not breakfast. In 1946, Hollywood health guru Gaylord Hauser published several recipes for "The Bircher-Muesli Breakfast" in his Gaylord Hauser Cookbook. Hauser had studied in Switzerland and was likely heavily influenced by Bircher-Brunner in his own health style, as he often emphasized fresh fruits and vegetables and even juicing. Muesli started to become known among health food enthusiasts after the Second World War, in part thanks to Hauser and others like him who visited Switzerland. Health guru Adelle Davis, however, is credited with introducing what we know today as "granola" to the masses in the 1960s. Although the Adelle Davis Foundation credits her 1947 book Let's Cook It Right with first mentioning granola, I can't find any reference in my copy. In fact, her short chapter on cereals makes no mention of cold, crunchy cereals like granola and contains just one recipe - for how to cook hot cereals (p. 427-439). Adelle is purported to have introduced granola as a snack, but her section on snacks in her introduction to Let's Cook It Right makes no mention of granola - instead suggesting fruit, milk, cheese and crackers, or nuts as good "midmeal" options (p. 17-22). Regardless of how she introduced it, Adelle is likely one of several people to discover that by combining rolled oats with nuts, dried fruit, oil and honey, you get a delicious crunchy baked snack. Her "grandaddy" recipe is below: Adelle Davis’ Grandaddy of Granolas 5 cups rolled oats 1 cup each of chopped almonds, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, shredded coconut, soy flour, powdered milk (preferably non-instant), and wheat germ. 1 cup warmed honey 1 cup oil, any kind Preheat the oven to 300 degrees. Combine dry ingredients. Combine honey and oil and drizzle over the dry ingredients tossing and coating. Spread the mixture on 2 cookie sheets and bake for 30 to 45 minutes until golden. Makes up to 12 cups, depending what you add or leave out. Eventually, people stopped eating granola out of hand and started pouring milk on top and eating in the morning. Of course, these days, modern granola is far more like Adelle's than Kellogg's (or Jackson's) in that it is heavily sweetened and usually quite fattening. But because of its health guru and sanitarium past and its association with hiking and other outdoor pursuits in the 1960s and '70s, we tend to associate it with healthy food, even though it is anything but. If you'd like to learn more about Gaylord Hauser and Adelle Davis, take a listen to my podcast, History Bites: Full of Pep, the Controversial Quest for a Vitamin-Enriched America, Part 2. So that's the end of my reward post for making it to 200+ likes on Facebook. MaryAnn - are you satisfied? :) I hope you enjoyed this post. If you did, please consider becoming a patron on Patreon to support this and other food history blog posts, podcasts, videos, and more. This week's #WorldWarWednesday post comes from Food Historian fan and First World War researcher and food conservation reenactor Sandra Dunlap, who sent me this gem of a recipe. I thought it would be a good follow-up to last week's post on conserving wheat.

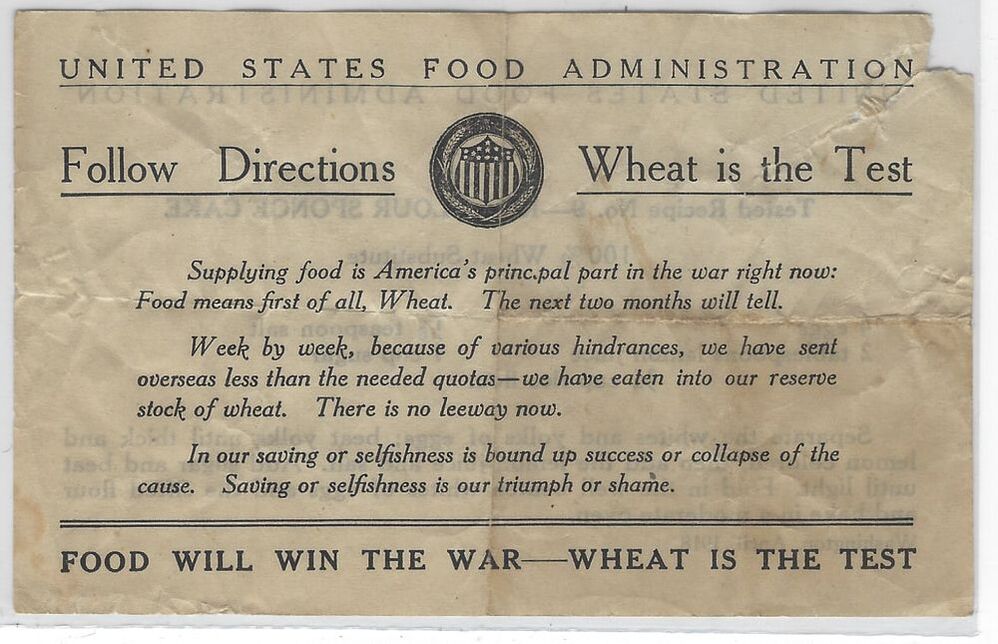

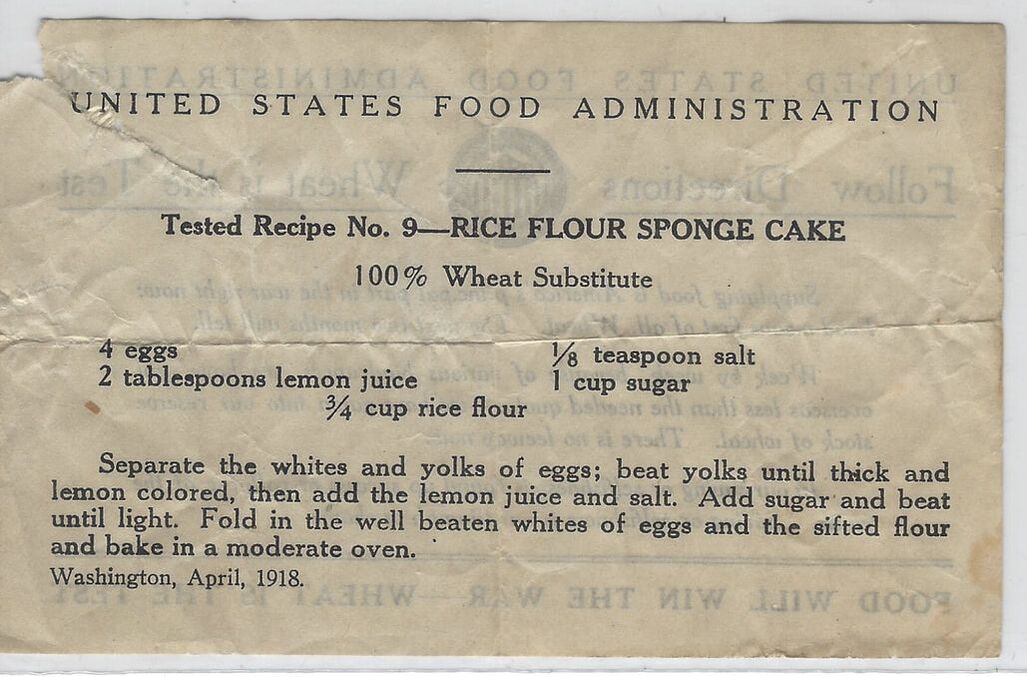

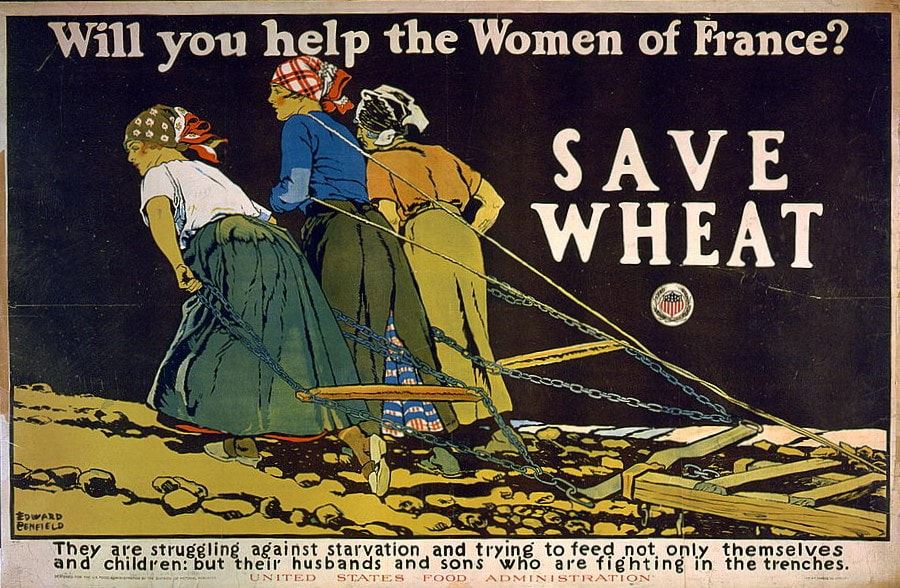

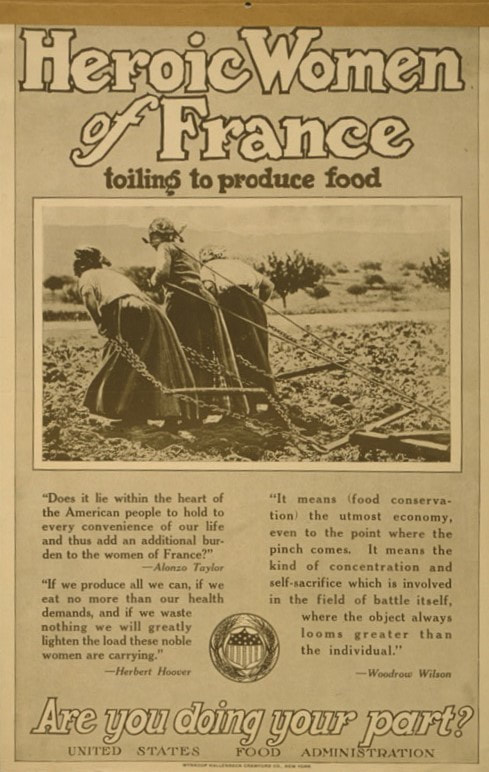

Tested Recipe No. 9 - Rice Flour Sponge Cake 100% Wheat Substitute 4 eggs 2 tablespoons lemon juice 1/8 teaspoon salt 1 cup sugar 3/4 cup rice flour Separate the whites and yolks of the eggs; beat yolks until thick and lemon colored, then add the lemon juice and salt. Add sugar and beat until light. Fold in the well beaten whites of eggs and the sifted flour and bake in a moderate oven. Washington, April, 1918. If you'd like to replicate it yourself, and Sandra and her daughter did, you'll need a few extra instructions. A "moderate oven" is 350 F, and Sandra and her daughter used an 8" round cake pan. And those egg whites will likely need to be beaten into stiff peaks. As for the unmentioned baking time? As Sandra recalls, it took about 45 minutes. These sorts of recipe cards and recipe booklets were extremely common during the First World War as a way for ordinary people to try to conserve wheat, which was in short supply and needed to be sent overseas to feed the Allies and American soldiers. Rice flour was not a common ingredient in American kitchens in 1918, but sponge cake certainly was. American housewives would have been very familiar with the basics of making a sponge cake and these simple cakes would either be served with just cream and fruit or might be cut up to make a trifle or other, fancier dessert. During wartime, because sugar was to be avoided, perhaps the cream would be sweetened with honey or maple sugar. Granulated sugar was necessary to make a sponge cake, however, which is why it is not omitted from this recipe. Any frosting was more likely to be a glaze or made with vegetable shortening than butter, which is also not needed for sponge cake. Conveniently for those who are gluten intolerant or who have celiac, this cake is not only 100% wheat free, it's also 100% gluten free! Although it's not in the title, Sandra called this a lemon sponge cake, and given that lemon is the most prominent flavor, it stands to reason that the cake would taste a little of lemon, too. I can imagine this being very nice with raspberry jam and a little whipped cream. Happy historic eating! If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! I was so pleased to be featured in the History Channel miniseries, The Food That Built America. It's a great mix of history and drama, with talking heads like me interspersed with quite wonderful reenactments of the famous personalities featured in the show. But a Facebook comment made me realize, that most people don't know these stories at all! The History Channel has featured some of them as articles on their website, but I thought, why not put together a bibliography for folks who wanted a deeper dive? Here are some of the books by authors featured in the show, as well as a couple of others that give great context to the period. (Please note that I am an Amazon Affiliate and will receive a small commission from any books published from these links.) The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek by Howard Markel (featured talking head). For God, Country, and Coca-Cola by Mark Pendergrast (featured talking head). The Emperors of Chocolate: Inside the Secret World of Hershey and Mars by Joël Glenn Brenner (featured talking head). H is for Hershey by Heather Paterno (featured talking head). Selling 'em by the Sack: White Castle and the Creation of American Food by David G. Hogan (featured talking head). Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet by Harvey Levenstein. Essential reading for understanding American food at the turn of the 20th century. Swindled: The Dark History of Food Fraud, from Poisoned Candy to Counterfeit Coffee by Bee Swinson. An eye-opening look at food before regulation. Birdseye: The Adventures of a Curious Man by Mark Kurlansky. Hershey: Milton S. Hershey's Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams Paperback by Michael D'Antonio American Empress: The Life and Times of Marjorie Merriweather Post by Nancy Rubin Stuart This is by no means a comprehensive list, but I thought it would be fun to compile a few "further reading" options for those who loved the show. Enjoy! Hello everyone and welcome to the very first post of World War Wednesdays. I'm aiming to get up to once a week on these, but I might not always make it, just to warn you. I decided I wanted to post on this blog more regularly, and a weekly posting is fairly doable and I LOVE the propaganda posters of both World War I and II, so here we are. I'll also include photographs, cookbooks or recipes, and maybe even WWII radio spots or films (whenever I can find them). I'll post the photos or other primary sources (with links, whenever possible, and caption citations always) and give you a little context to the whys and wherefores of the background of the image. Today, we're starting with one of my favorite and most interesting propaganda posters from the First World War: It reads, "Will you help the Women of France? SAVE WHEAT. They are struggling against starvation and trying to feed not only themselves and children: but their husbands and sons who are fighting in the trenches." Designed by Edward Penfield and published by the United States Food Administration, this propaganda poster was released sometime in 1918, after the United States was well into the War (we joined on April 6, 1917). In it, three French peasant women, in skirts and kerchiefs, have hooked themselves to a plow in lieu of horses. It is a striking image and one that was effective in tugging at American heartstrings, where white Anglo-Saxon women rarely engaged in this kind of brute manual labor. But why wheat? The wheat harvests in the United States in 1915 and 1916 were poor ones, after several years of bumper crops. Geographically, the United States was the closest source of wheat to continental Europe. Canada was of course committed to Britain and other wheat-producing countries like the Ukraine were either engaged in the war themselves or like India were unable to ship to Europe due to the prevalence of German U-Boats. However, since the United States joined the war in April, it was too late to influence farmers to plant more in the spring of 1917. In addition, the United States did not have and would not nationalize agriculture, and could therefore only make recommendations to independent farmers as to what to grow. For most Midwestern farmers, the skyrocketing demand for wheat was driving up prices for their limited supply, and life was good for the first time in many years. They were reluctant to tank those high prices by overproducing. So, it fell to the United States Government, through the United States Food Administration, headed by Herbert Hoover, to persuade ordinary Americans to eat less wheat, along with meat, butter, and sugar, so as to free up these high-calorie, shelf-stable products for consumption by American soldiers and the Allied Forces. Meatless Mondays were a product of the First World War, as were "Wheatless Wednesdays." Although the first poster is more famous, this earlier one features a photograph of the women from which the propaganda poster was made. Here, the poster reads in large letters, "Heroic Women of France toiling to produce food. Are you doing your part?" The interior holds quotes from several notable individuals. "Does it lie within the heart of the American people to hold every convenience of our life and thus add an additional burden to the women of France?" - Alonzo Taylor "If we produce all we can, if we eat no more than our health demands, and if we waste nothing we will greatly lighten the load these noble women are carrying." - Herbert Hoover "It means (food conservation) utmost economy, even to the point where the pinch comes. It means the kind of concentration and self-sacrifice which is involved in the field of battle itself, where the object always looms greater than the individual." - Woodrow Wilson. Produced by the United States Food Administration sometime in 1917, this poster takes a slightly different tack. Still guilt-tripping ordinary Americans, it uses quotes from Food Administration expert Alonzo Taylor, the Food Administrator himself, Herbert Hoover, and President Woodrow Wilson to appeal to Americans' better natures of self-sacrifice. In Progressive Era America, people generally trusted the authority of experts, making this tactic more effective than it perhaps would be today. This striking photograph from sometime in 1916 is the iconic image from which these propaganda posters were derived. The caption reads, "Peasants in the re-taken Somme District work hard without horses or cattle. The Germans in retreat have taken all live stock." Without cattle or horses, these French women, having survived the battles of the infamous Somme, are trying to return to some semblance of normal life, hitching themselves to the plow to ensure a harvest for winter.

Or so it seems. It is unclear whether or not this photo is staged for effect. It is entirely possible that it is legitimate, but it is just as possible that it has been staged as propaganda. The women do appear to be pulling, however - the lines are fairly taut, and they appear to be wearing everyday clothing, not costumes. Regardless of whether or not the photo is true to life or staged, this image had a striking impact on Americans (and Canadians) in helping the United States Food Administration convince them to reduce consumption of wheat for the duration of the war. Remember my post about George Washington and cherries in February? It's been one of my most popular. And while yes, you can totally still make walnut pie or have pickled walnuts with cheese and Madeira in February, you can also take the time right now to make yourself some Cherry Bounce.

What is cherry bounce, you ask? It's basically brandy, cherries, and sugar, and it was a favored 18th century drink. My in-laws have a now quite grown up sour cherry tree (Montmorency, I think) that was just LOADED with sour cherries when we were up the other weekend. Sour cherries, also known as sour pie cherries, are not as sour as, say, rhubarb, but definitely need a little sugar as they are nowhere near as sweet as the sweet black or Queen Anne cherries you often find in grocery stores this time of year. They're also far more delicate, so if you're going to pick them, please pick them with the stem on, unless you plan to process them right away. Martha Washington's recipe is available thanks to the Mount Vernon estate, but I didn't have 10 pounds of cherries, and while mine probably weren't Morellos, Montmorencies are a sub-genus of Morellos. I also thought 3 cups of sugar to 4 cups of brandy was pretty high. That's borderline syrup territory, for my taste. Considering I wanted to use this cherry bounce as a sipping liquor or in cocktails, I reduced the sugar. I also wanted to taste some of that summer flavor, so I left out the spices. Here's what I used: 1 colander sour cherries (a little more than 1 quart, pitted and stemmed - feel free to use more) a little more than 1 cup sugar 1 liter smooth brandy (not the expensive kind, but not the cheapest either) Place 1/2 cup sugar in each of two quart jars. Pit the cherries and divide equally between the jars (you'll get about a pint for each). The easiest way to do this, since sour cherries are so soft, is just to squeeze the pits out over the jars, to make sure you catch all the juice. Discard the pits. This is also easier if you use a canning funnel for each jar, which helps with the splatters. Because Montmorency cherries have yellow flesh, if you wear dark clothing, the spattering won't stain. Once the cherries are done, add 2 cups of brandy to each jar. You'll have a little left over, so just divide the remainder between the two jars. I added another couple of tablespoons of sugar to each, because I had room. Screw the mason jar lids on and shake every hour or so until the sugar is dissolved. Then let rest in a cool dark place, shaking occasionally, until February. I left the cherries in, and intend to either serve one with each glass, or strain them out and cook them in more sugar and serve over vanilla ice cream (Thomas Jefferson's favorite). Funnily enough, although the mixture was brown last night, by morning it was bright red and the cherries were already starting to lose their color. We'll see how it turns out. I might regret not adding more sugar or cherries, as sugar tends to mellow out alcohol, but then again, I might not! I'll give an update for President's Day 2020, when I'll invite some friends over for cherry bounce, walnuts, and ice cream! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed