|

Our 30th episode! Hard to believe we started in March, 2019 at episode 1! In this episode of Food History Happy Hour, we made the Pink Garter cocktail from 1946 and discussed all things wedding food! We started off with WWII rationing and wedding cakes, moved into 19th century wedding breakfasts, why they were called "breakfasts," and the types of food served, including the Medieval origins of wedding cakes, which were originally (and sometimes still are) fruitcake! Then we moved onto trends in cake design, the influence of Queen Victoria on fashionable weddings, and launched into a discussion of famous literary weddings (including Laura Ingalls Wilder and Meg March from Little Women) which then devolved into an (attempted) discussion of what was served at Miss Havisham's wedding breakfast.

In earnest pursuit of Anna Katherine's request to know what was at Miss Havisham's wedding breakfast, I could find no official reference. The original text only refers to the bride's cake and an epergne filled with something cobwebby and rotting. Almost certainly fruit if, like Elizabeth theorized, Miss Havisham's wedding had taken place in the 1810s.

I did, however, find an etiquette book from 1834 that had this to say about weddings: "The breakfast should be supplied by a first rate confectioner and the table should be as beautiful as flowers plate glass and china can make it. The ordinary menu of a wedding breakfast is as follows. Tea, coffee, wines, cold game and poultry, lobster salads, chicken and fish à la Mayonnaise, hams, tongues, potted meats, game pies, savory jellies, Italian creams, ices, and cold sweets of every description." So lots of meat, seafood, and sweets, all served cold. I can only imagine what rotting lobster or fish smelled like in Miss Havisham's house. Yuck. And while I wasn't able to find an actual menu from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert's wedding, I did find a clip from the show Anna Katherine was referring to! The Pink Garter (1946)

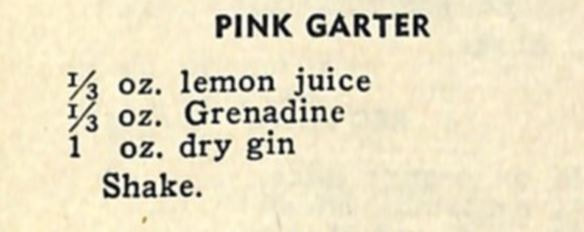

Tonight's cocktail came from perennial favorite The Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly, published in 1946. This was a very straightforward, very delicious drink. Super simple, but surprisingly complex-tasting. If you like raspberry lemonade, this drink will be right up your alley. If sweet drinks are not your thing, cut down on the grenadine, or up the gin ratio. It calls for:

1/3 ounce lemon juice 1/3 ounce grenadine 1 ounce dry gin Shake with ice and strain into a martini glass. I garnished mine with a maraschino cherry for extra pizazz. Still looking for more wedding food history? You can watch my illustrated talk as recorded recently for a library lecture!

That's all for this month's Food History Happy Hour! I've got a TON of talks coming up in June, so be sure to check out the events calendar, and we'll see you at the next Food History Happy Hour on June 18th!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

Don't want to join Patreon? Use our new Tip Jar instead! You can make a one-time donation any time, not strings attached.

0 Comments

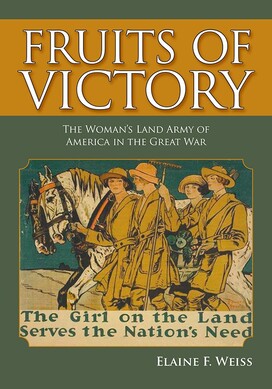

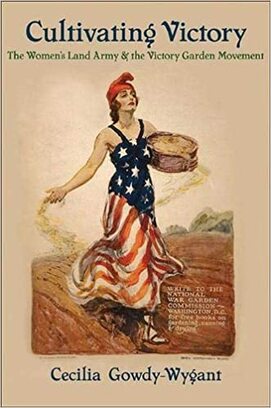

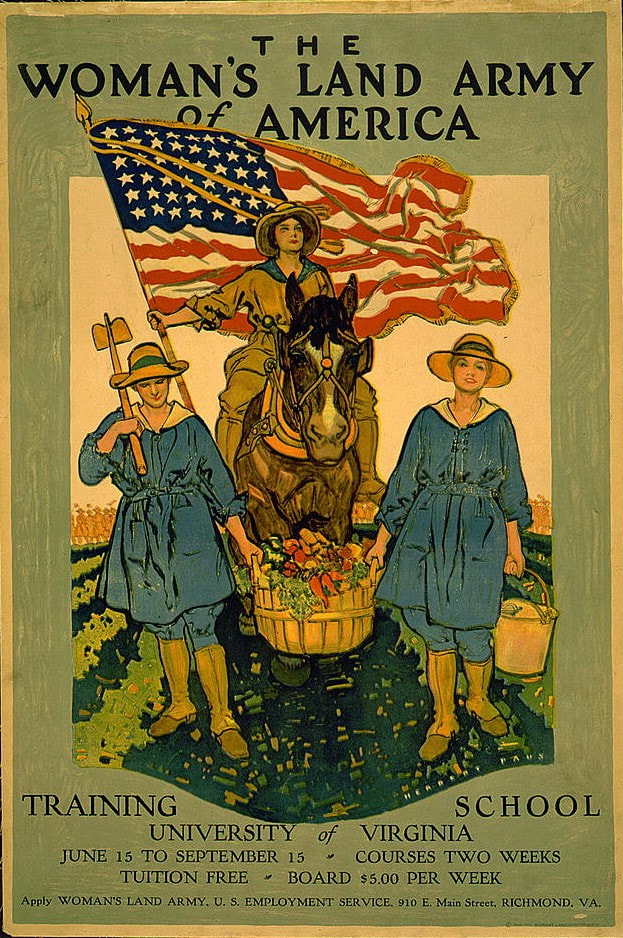

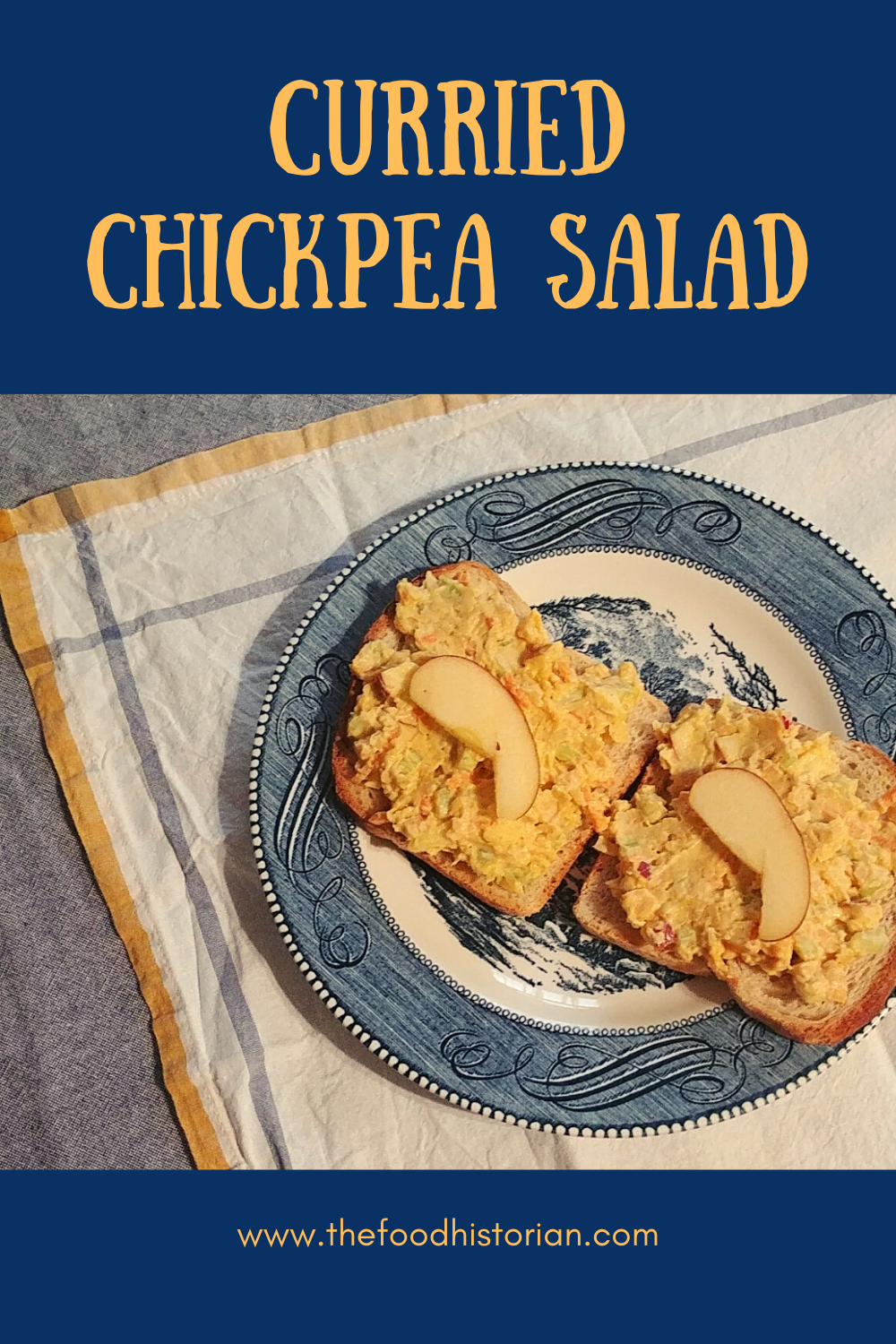

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase something from a link, you'll be supporting The Food Historian! The Woman's Land Army of America came out of the women's suffrage movement as a way for young, largely college-educated women to prove their worth during wartime by providing agricultural labor to make up labor shortages thanks to the draft, better wages in industrial work, and the need to increase agricultural production. The movement started in New York State, and has been ably chronicled by Elaine Weiss' book The Fruits of Victory. This beautiful propaganda poster from the University of Virginia Training School for the Woman's Land Army of America is just delightful. The imagery is evocative. A young woman holding an American flag, which billows out behind her, is dressed in a khaki uniform and riding a plow horse through a green agricultural field, simultaneously calling to mind a mounted standard bearer, Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders, and Army cavalry. In the foreground, two young women in matching blue uniforms share the load of a bushel basket laden with vegetables. The woman at left has a hoe over her shoulder, reminiscent of how a soldier might carry a rifle. The woman at right carries what appears to be a milk pail. Far in the background, what appears at first glance to be a field of ripe wheat is in fact a golden line of uniformed women with agricultural implements on their shoulders, marching behind the leading three. The costumes were among the official Woman's Land Army costume - in khaki and blue chambray. A loose tunic with full sleeves (rolled up) and a cinched waist falls to the knee, covering military-style jodhpurs and puttees over sensible shoes. A broad-brimmed hat and a kerchief around the neck complete the sensible outfit, which somehow still scandalized some members of the public at a time when women's skirts rarely rose above the ankle. The poster is advertising the Woman's Land Army's Training School at the University of Virginia. Designed to give young women basic agricultural skills, and sometimes specialized skills like the use of tractors, the schools were generally free, but required payment for room and board, as this one does at $5.00 per week for a two week course. Sometimes called "farmerettes," likely a combination of the terms "farmer" and "suffragette," and one which not every member of the Woman's Land Army enjoyed. But then, not every farmerette was a member of the Woman's Land Army, and the term actually predated the U.S. entrance into the war. The women saw some success in the adoption of their labor in agriculture, but it created no sea change of labor distribution post-war. Most farmers outside orchards and truck farmers mechanized in the face of labor shortages, rather than using farmerettes or farm cadets (teenaged boys released from school to work on farms). And increasing specialization of crops and livestock meant that mechanization was easier and more profitable than hiring young women at good wages for just 8 hour days (pre-war farm laborers had no such protections). The Land Army would be revived during World War II, this time divorced from its suffragist origins and encouraging young people of both sexes to assist with farm labor. But that's a post for another day. Woman's Land Army Books Fruits of Victory: The Woman's Land Army of America in the Great War by Elaine F. Weiss Weiss tracks the evolution of the Woman's Land Army in America, focused primarily on New York State, which was where the WLA officially began in the U.S. In intimate detail, she introduces us to a whole host of historic characters, including leading lights of the women's suffrage movement, and how they tried to prove women's agricultural labor was the future.  Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement by Cecilia Gowdy-Wygant Cultivating Victory examines the interrelationships between the British and American Woman's Land Armies, as well as their connections to the war garden and victory garden movements. Covering both the First and Second World Wars, Gowdy-Wygant compares and contrasts the efforts in both nations and the differences and similarities between both wars. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! I made curried chickpea salad last week, and it was so delicious, I thought I would share it for Meatless Monday. Although it is not a historic recipe, clearly it's a riff on curried chicken salad, which had its heyday in the mid-20th century, although you still see it on restaurant menus, especially tea rooms and bakeries and small cafes. It's not super clear when precisely curried chicken salad was invented, but there are lots of references throughout 19th century American cookbooks to all sorts of curried dishes - eggs, oysters, veal, cucumbers, shrimp, okra, and yes, chicken, although not in a salad until the 20th century. Country Captain is one of the first curry dishes in the United States, and may have inspired curried chicken salad in the 20th century. Made with browned chicken, onions, curry powder, tomatoes or tomato sauce, and golden raisins or currants, it was meant to be served over rice and likely originated in the Carolinas, where rice cultivation (fueled by slave labor) was common. It is called "country captain" because it was apocryphally introduced via a sea captain returning from India and/or involved in the spice trade. This savory, sweet, and mildly spicy flavor combination has been deemed by some historians to be the first fusion food in U.S. history. But it is unclear where curried chicken salad as made in the United States draws its roots. It may very well be from the flavor profile of Country Captain, and mayonnaise-based salads were exceedingly common by the turn of the 20th century. Some enterprising soul may have come up with the idea independently. However, in 1935, King George V of Britain celebrated his silver jubilee, and although I cannot find an original menu from the event, everyone swears a cold chicken dish with curried mayonnaise was part of the dinner (which some people thought was an unnecessary extravagance during the Great Depression). The dish was recycled (perhaps inadvertently) for Queen Elizabeth's coronation in 1953, this time with some fancier additions of tomato, pureed apricot, red wine, and whipping cream (try the original recipe). Jubilee chicken and coronation chicken, as the recipes have come to be known, are still quite popular in Britain, although they rarely show up on American shores under that name. At the same time, prior to Queen Elizabeth's coronation, we do have recipes in the United States calling simply for cooked diced chicken, mayonnaise, curry powder, and diced celery (like this one). Basically, plain jane chicken salad with some curry powder thrown in for flavor. This 1930 cookbook has a recipe for chicken salad with grapes or raisins, and a recipe for curry salad dressing (curry powder, vinegar, and mayonnaise), but the two aren't put together. So again, the official origins are unclear. But suffice to say, a curried chicken salad with celery and some variation of either golden raisins, currants, diced apple, and/or grapes has become an alternative to the more traditional (and boring) basic chicken salad. I chose to replace the chicken with canned chickpeas in part because poaching chicken is a drag and I hate the canned stuff. But also because not only are canned chickpeas easier and more accessible than poached chicken, they're a little healthier for the gut, too. Vegetarians and vegans often use chickpeas as a substitute for chicken or tuna. It turned out even better than I remembered from the last time I made it, and it seems appropriately vintage, even if it isn't actually historic. Curried Chickpea SaladA quick weeknight supper perfect for when it's too hot to cook, but equally at home at a tea party. To make this vegan, substitute all vegan mayonnaise for the yogurt and mayo. 2 cans (16 oz.) chickpeas, or 3 cups cooked from dried 3 ribs celery, minced 1/2 cup shredded carrots (I use the bagged kind) 1 small, sweet, crisp apple, minced 1/2 cup Greek yogurt 1/2 to 1 cup mayonnaise 1/2 to 1 tablespoon high quality curry powder salt & pepper to taste Drain and rinse the chickpeas, then mash roughly with a fork. I don't like any whole chickpeas in mine, but neither do I want a puree. Add the celery, carrots, and apple and mix well with a fork to combine. Add the yogurt and curry powder and mix, then add the 1/2 cup of mayo and mix. If too dry, add more mayo. Taste and add more curry powder, salt, and pepper if necessary. The warm spices of the curry powder set off the creaminess of the mayo and yogurt and the sweetness of the apple nicely, and the celery and carrots add crunch and texture. I like mine served open-faced on whole grain toast. The hubby prefers his sandwich closed on untoasted bread. You can also eat it with crackers, in a wrap, or frankly, with a spoon. If you want to try something more country captain style, add golden raisins and a little tomato paste. For something more coronation-style, try diced dried apricots or a few tablespoons of mango chutney. Add lemon or lime juice for tang, or leave it out. But whatever you do, don't use that little jar of curry powder that's been in the back of your spice cabinet for years. Get yourself a new jar or better yet, go to a store with a bulk spices section and get some fresh stuff that way. Have you ever had curried chicken salad? Or chickpea salad? Tell us your favorite quick weeknight dishes in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

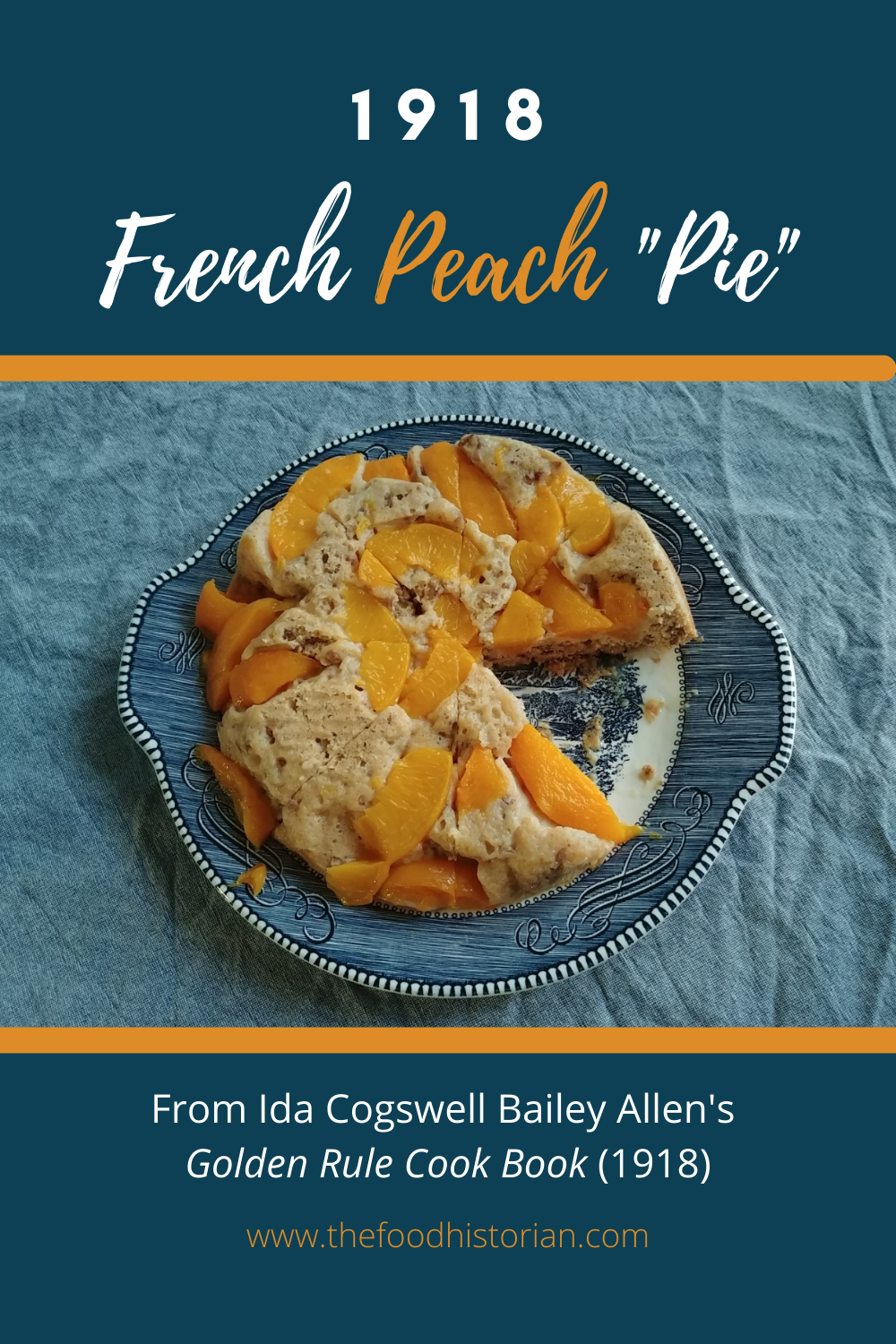

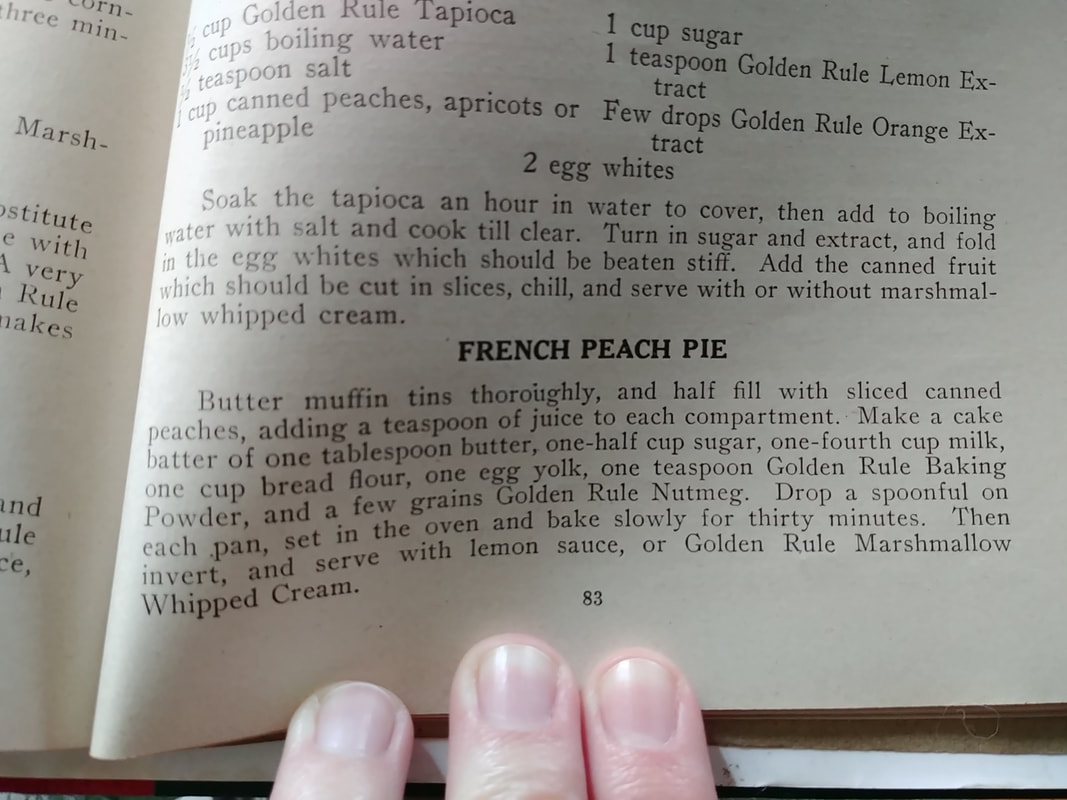

We get to visit Disney in World War II again this week! In this charming little film, "Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Firing Line," first released in July of 1942, we see familiar characters Minnie Mouse and Pluto learning about the role of kitchen fats in munitions manufacturing.

The little films opens with Minnie frying up a pound of bacon on the stove, and then offering to pour the hot grease over Pluto's bowl of dog biscuits, much to his delight. But an authoritative voice from over the radio interrupts, telling of the value of saving kitchen fats for use in the manufacture of glycerin, a primary ingredient in explosives.

Although Pluto starts out angry at being denied the delicious bacon grease, a reminder that waste fats give soldiers more ammunition, with a quick pan over to the photo of Mickey Mouse in his soldier's uniform, convinces him otherwise. A quick salute to Mickey and Pluto is ready to help Minnie save the fats. He even brings the can of fat to the butcher in exchange for a string of hot dogs. This adorable little film, which was likely geared towards children as well as adults, helped convince Americans to alter their usual behaviors in the home and contribute to the war effort by saving every scrape of waste fats possible. To learn more about Disney in World War II, check out our previous post.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

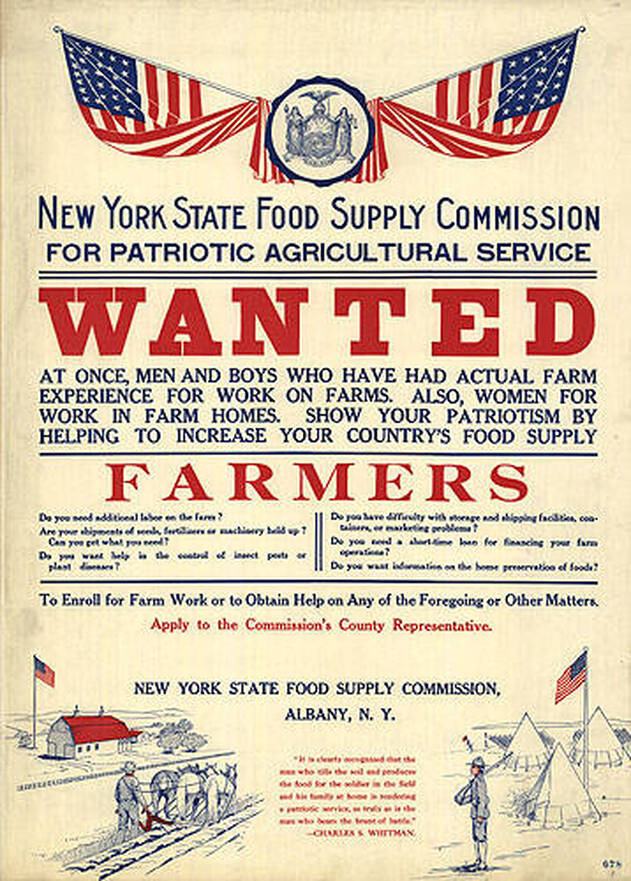

"New York State Food Supply Commission for Patriotic Agricultural Service. Wanted at once, men and boys who have had actual farm experience for work on farms. Also, women for work in farm homes. Show your patriotism by helping increase your country's food supply. Farmers - Do you need additional labor on the farm? Are your shipments of seeds, fertilizers or machinery held up? Can you get what you need? Do you want help in the control of insect pests or plant diseases? Do you have difficulty with storage and shipping facilities, containers, or marketing problems? Do you need a short-term loan for financing your farm operations? Do you want information on the home preservation of foods? To Enroll for Farm Work or to Obtain Help on Any of the Foregoing or Other Matters. Apply to the Commission's County Representative. New York State Food Supply Commission, Albany, N.Y." 1917, Temple University. The United States entered the First World War on April 6, 1917. On April 13, New York State Governor Charles S. Whitman appointed a Patriotic Agricultural Service Committee. On April 17, an Act of the New York State legislature created the New York State Food Supply Commission. This propaganda poster is likely from the spring of 1917 for several reasons. First, by the fall of 1917, the commission had changed its name to the New York State Food Commission, Second, the emphasis on laborers with farming experience, rather than the inexperienced, was a hallmark of early efforts to increase agricultural production. The poster reads: "New York State Food Supply Commission for Patriotic Agricultural Service. Wanted at once, men and boys who have had actual farm experience for work on farms. Also, women for work in farm homes. Show your patriotism by helping increase your country's food supply. Farmers - Do you need additional labor on the farm? Are your shipments of seeds, fertilizers or machinery held up? Can you get what you need? Do you want help in the control of insect pests or plant diseases? Do you have difficulty with storage and shipping facilities, containers, or marketing problems? Do you need a short-term loan for financing your farm operations? Do you want information on the home preservation of foods? To Enroll for Farm Work or to Obtain Help on Any of the Foregoing or Other Matters. Apply to the Commission's County Representative. New York State Food Supply Commission, Albany, N.Y." Interestingly, this poster not only focuses on farm labor, seed acquisition, farm loans, etc., but also on securing women's labor "for work in farm homes." The general idea was that women could help relieve some of the household burden on farm wives, and assist with food preservation, so that farm wives, who were often more experienced in farm management than most farm laborers, could assist their husbands. Neither plan really worked out well. The few women who were interested in farm labor wanted to do the agricultural work - not housework. And while experienced farm hands were in high demand, that drove wages up considerably - not every farmer was able to afford them. The Food Supply Commission coped by helping some farms modernize. They purchased a series of tractors - then still a rarity in the Northeast - and helped farmers acquire seed potatoes, beans, and more. But it took until the end of 1917 for the Commission to find its footing. By then, it became a partner of the United States Food Administration, working hand-in-hand with Hoover. You can read more about the New York State Food Supply Commission and its early work in its annual report for 1917, published in 1918. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! As you may know, I am a huge fan of Ida Cogswell Bailey Allen. A PROLIFIC cookbook author with over fifty titles to her name, I'm not sure anyone has ever done a comprehensive bibliography of her work. So when I saw this little cookbook on Etsy, I squealed. I squealed in part because, as far as I can tell, this is one of her first cookbooks! And I also got excited because she is listed as an "endorsed lecturer" for the United States Food Administration! The cookbook does have a few ration-friendly recipes in the very back - basically for wheatless baking recipes. But the majority are regular ol' recipes designed for The Citizens' Wholesale Supply Company from Columbus, Ohio. There's not a lot out there on this company, but from what I can tell it started out as a co-op, and then morphed into a company focused on food products - the Golden Rule brand. The Golden Rule Cook Book, (not to be confused with THIS Golden Rule Cook Book of meatless and vegetarian recipes), doesn't appear to be digitized anywhere, nor are there many versions for sale online. Which makes it all the more interesting! It was likely designed as an advertising cookbooklet, which were a common advertising device for food products and companies from the 1890s until quite recently. As you can see, the recipes all call for at least one Golden Rule brand ingredient, often a flavoring extract. This "French Peach Pie," however, caught my eye. It appeared to be an upside down cake, albeit baked in muffin tins. Ida Bailey Allen probably called it "French" because it loosely resembles tarte tatin. I wasn't sure exactly how many muffin tins, as I knew some historic tins were only 6 muffins big, and I had only a 1 dozen pan. So I decided to make a few changes. First, I made it in a round cake pan, instead of individual cakes in a muffin tin. I also added chopped pecans, because I had some and that sounded good with peaches. I added a pinch of salt, because Ida never does and baked goods taste flat without it. More commentary with the recipe. French Peach "Pie"I put the "pie" in quotes because this is really an upside down cake. If I make this again, and I think I will, I am going to make a few more changes, mainly using regular all-purpose flour and using the full egg, instead of just the yolk, as the batter was a bit dry and needed an infusion of extra milk. I even added a little of the leftover peach juice! Here's the verbatim recipe: Butter muffin tins thoroughly, and half fill with sliced canned peaches, adding a teaspoon of juice to each compartment. Make a cake batter of one tablespoon butter, one-half cup sugar, one-fourth cup milk, one cup bread flour, one egg yolk, one teaspoon Golden Rule Baking Powder, and a few grains Golden Rule Nutmeg. Drop a spoonful on each pan, set in the oven, and bake slowly for thirty minutes. Then invert, and serve with lemon sauce, or Golden Rule Marshmallow Whipped Cream. Here's my translation: 1 quart canned peaches 1 tablespoon butter, softened 1/2 cup sugar 1 egg yolk 1/4 to 1/2 cup milk Leftover peach juice 1 cup bread flour 1 teaspoon baking powder pinch of salt (1/4 teaspoon at least) 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon 1/4 cup chopped pecans (optional) Well-butter a 9 inch round cake pan. Add the peach slices to the bottom of the pan (I was missing a few from my quart from an earlier snack), and a few tablespoons of the juice. In a large bowl, cream the butter and sugar (it WILL work, just takes a minute), then mix in the egg yolk. At this point I dithered between adding the milk or adding the flour, or alternating. I ended up adding the milk and blending well before adding the flour, baking powder, cinnamon, and chopped pecans. This was VERY thick and did not even absorb all the flour, so I added another a little more milk and the remaining peach juice (about 1/4 cup) to make something more closely resembling a thick batter. I dolloped spoonfuls into the pan and tried to spread it out as best I could. I then baked it at 350 F (a "slow" oven is usually between 300 and 350 F), and 30 minutes wasn't quite long enough, as it was a larger pan, so I baked it for probably 40ish minutes, or until the cake was starting to turn golden brown at the edges. I then used a knife to loosen the edges of the cake, placed a cake plate on top of the pan, and flipped to release. Only a little of the cake stuck to the bottom - likely because I added a smidge too much milk. The cake was oddly firm-textured, I think because of the use of bread flour, and a bit dense. Next time I make it I am definitely using all-purpose flour and a whole egg and we'll see how that turns out. And I'll add a little more salt next time. And more peaches! There were insufficient peaches. Lol. And I think this recipe would be much better with fresh peaches, but canned were perfectly fine. The Golden Rule Marshmallow Whipped Cream I did not try, but it is simply whipped cream stabilized with a tablespoon or so of marshmallow creme. Liquid cream is much better, in my opinion! Especially since this cake was quite sweet. Interestingly, although this dessert is not in the World War I section of wheat-saving recipes, it calls for just one tablespoon of butter and one egg yolk, at a time when butter was rationed and eggs were often scarce. It would also be easy to shift this recipe to all barley flour or all or part rye flour to substitute for the wheat. The sugar could also probably be substituted in part or all for honey or maple syrup, which would give added moisture to the batter as well. What do you think? Would you try French Peach "Pie?" Maybe next time I'll be brave enough to try it in the muffin tin! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed