|

Thanks to everyone who joined me for Food History Happy Hour tonight! We talked about the history of diets, dieting, and diet culture, with forays into 19th century religious diets (including Sylvester Graham, Ellen H. White, and John Harvey Kellogg), raw food diets, veganism, changes in fashion influencing ideas about body types, the role of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and WWI in informing modern ideas about dieting, willpower, and health, the invention of the calorie, the development of dieting and diet fads in the 1930s and '40s, including juicing and the Hollywood diet, we talked about Dr. Norman W. Walker, Gaylord Hauser, Dr. Weston Price, Adele Davis, the role of animal fats in heart disease research, the history of artificial sweeteners, environmental factors in fatness and obesity, and that diet culture is super toxic! I probably could have talked for another hour on this subject, so we can revisit it, if you want to! Let me know in the comments.

We also made a (red) wine spritzer (I thought it was a bottle of white wine, it wasn't) and the history of wine spritzers. Wine Spritzer (19th century)

White wine spritzers are the classically low-calorie bar favorite in the late 20th century United States, but they date back to the early 19th century and are likely associated with the health and spa culture surrounding sparkling mineral waters, but may have also been simply an attempt to make an artificially sparkling wine!

Take your favorite wine - red or white - chilled, and cold club soda or seltzer or sparkling mineral water, also chilled. You can combine them in any ratio, but I think half and half is probably best. Further Reading:

Obviously, I had a blast doing this episode and I think I need to now do some biography blog posts about fad diets and nutritionism and their proponents. Did you know Gaylord Hauser had a TV show? You can alsowatch an interview with Adelle Davis!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

0 Comments

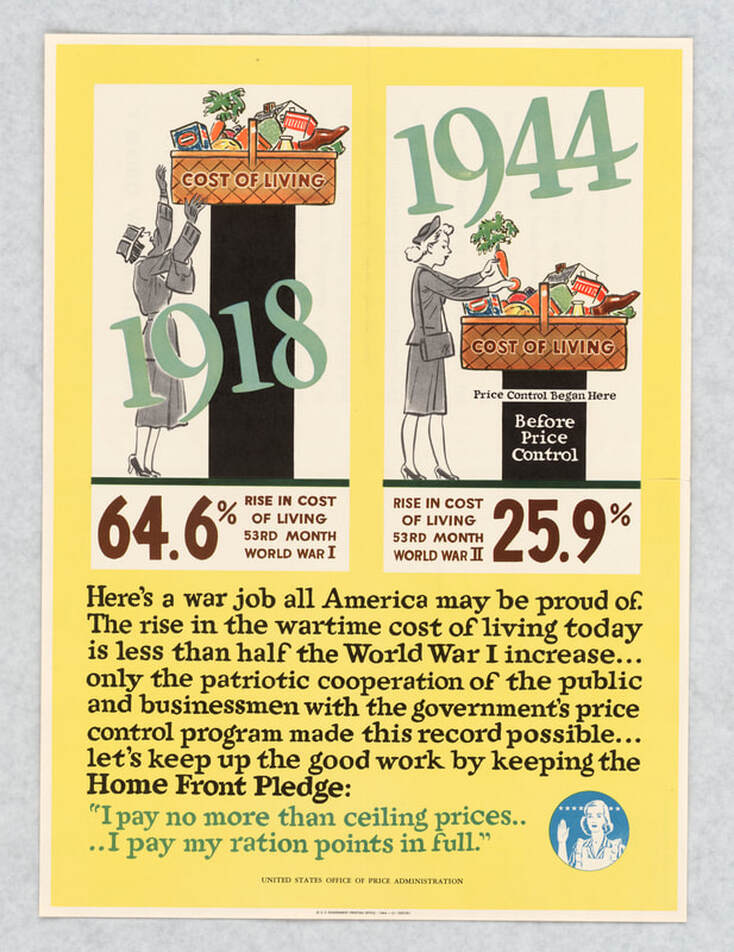

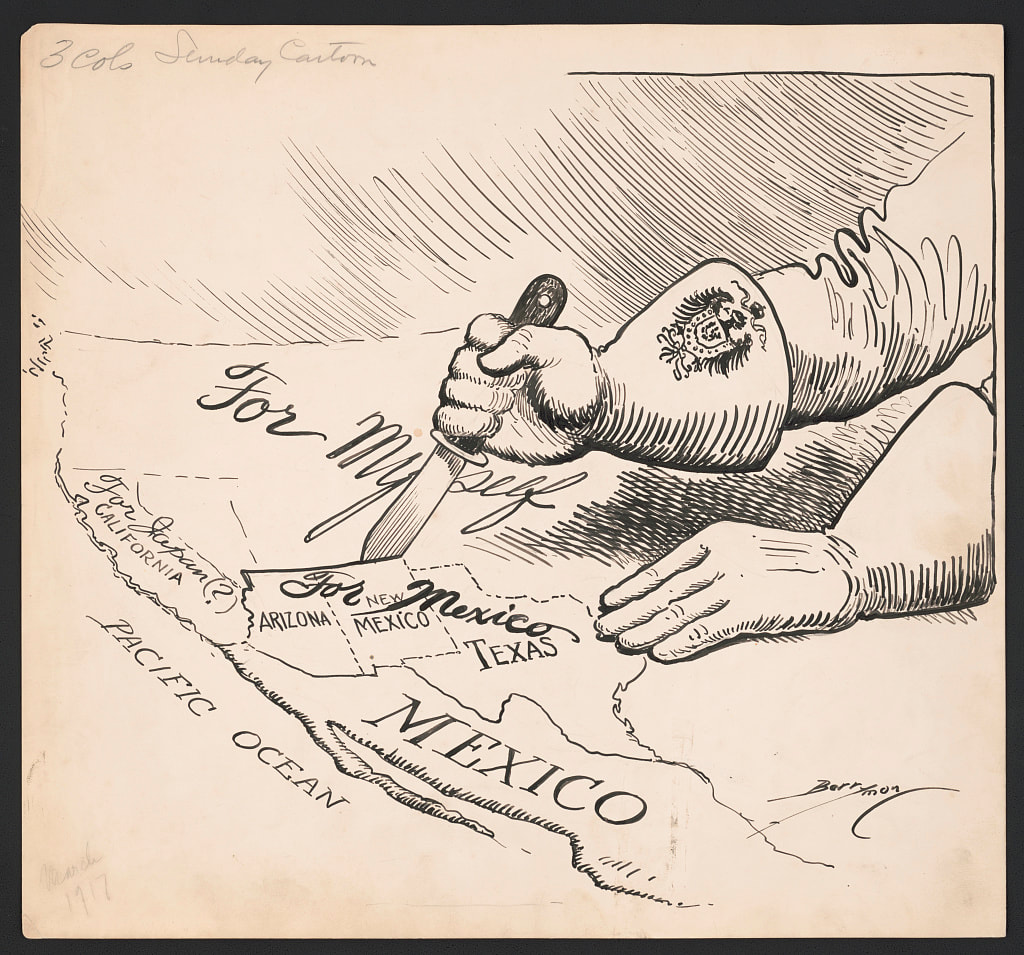

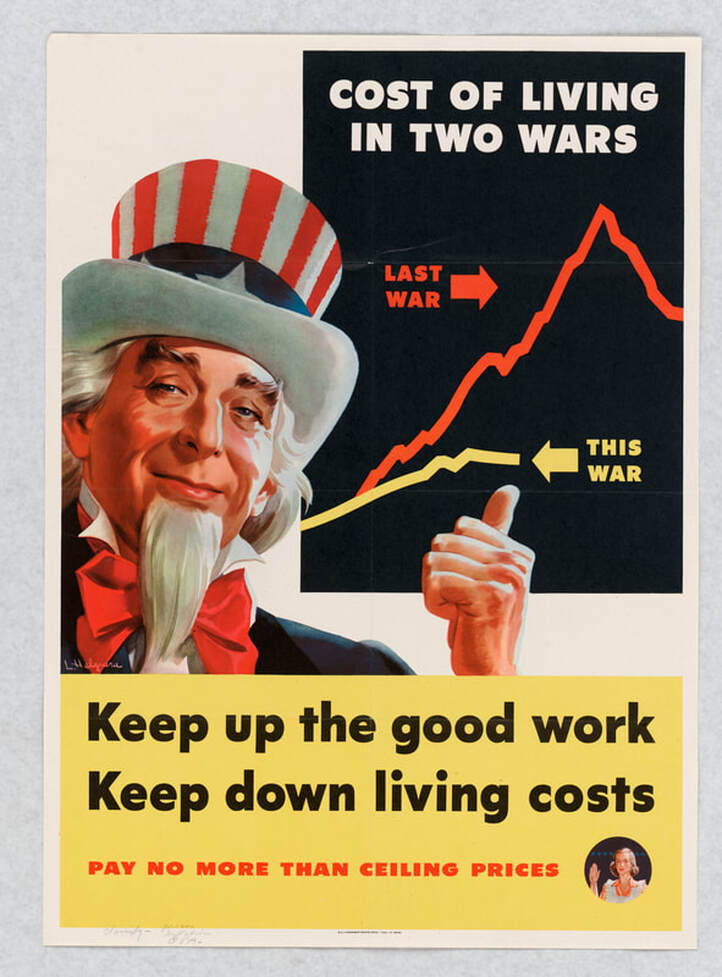

Last week we talked about the High Cost of Living in the First World War. Those memories were close at hand during the Second World War. During World War I, the federal government did little to control prices at the consumer level, and rationing was voluntary. The U.S. Food Administration did control whether or not retail establishments and manufacturers complied with rationing and other rules through a complicated system of licensing and oversight, but individual consumers were technically allowed to make their own food choices. During World War II, things were different. Rationing was mandatory, even if the stamps were often confusing, and black markets definitely existed. But the creation of the Office of Price Administration froze the official prices of a whole host of goods, including food, to try to offset wartime inflation. Once again retailers were being regulated by the government, but this time the OPA relied on consumers to help report violators. By enlisting housewives to help enforce "ceiling prices" by refusing to purchase goods at that exceeded the published price lists, the OPA got a free labor source, and the housewives ensured that their retailers were not cheating them. Black women, in particular, benefitted from this practice, as discrimination meant they were subject to being cheated.  "Here's a war job all America may be proud of. The rise in wartime cost of living today is less than half the World War I increase... only the patriotic cooperation of the public and businessmen with the government's price control program made this record possible... let's keep up the good work by keeping the Home Front Pledge: "I pay no more than ceiling prices... I pay my ration points in full."" Office of Price Administration, National Archives. This pair of posters, comparing the inflation of food from WWI to WWII, was designed to prove the effectiveness of the Office of Price Administration and its price control efforts. In the first one, Uncle Sam points to a chart that compares the rise of inflation over the course of both World Wars. In the second, two bar charts on inflation are compared. In the first, labeled 1918, a (suspiciously-1930s-attired) housewife tries and fails to reach a basket of food labeled "Cost of Living" as it rises on a bar chart of 64.6% inflation. Whereas the 1944 housewife can easily reach her basket at 25.9% inflation. Interestingly, her bar chart has a white line 3/4 of the way up which reads "Price control began here." The black bar below reads "Before Price Control," implying that inflation could have been much worse without the intervention of the OPA. Both statistics are attributed to the 53rd month of the war, which seems to indicate that the inflation statistics for World War I start in 1914, not 1917, when the U.S. officially joined the war, which tracks with the cost of living increases that began long before April 7, 1917. These two posters indicate just one of the ways in which the lessons of the First World War were applied to the Second. Some lessons, however, remained hard to swallow. During WWI, the United States Food Administration, although formed by executive order in May of 1917, received no funding from Congress until August, 1917, because a number of congressmen objected to the sweeping powers and controls it gave the executive branch. In an effort to avoid a bloated post-war bureaucracy, it was quickly dismantled in early 1919, despite the fact that the cost of living rose precipitously after the war. Similar sentiments about the power of the Office of Price Administration were debated during WWII, and numerous attempts by organized retail and manufacturing organizations to weaken it started as early as 1944. The OPA was allowed to temporarily expire in 1945, and prices jumped almost instantly. It was hastily reinstated, but in a weaker form, and was fully abolished in 1947. Some price control functions for sugar, rice, and a few other products were shifted to other agencies. In her article, "'How About Some Meat?': The Office of Price Administration, Consumption Politics, and State Building from the Bottom Up, 1941-1946," historian Meg Jacobs talks about how the Office of Price Administration helped Americans determine that high standards and low cost of living was their reward, nay birthright, for surviving two World Wars and a Great Depression. Caught between empowered consumers and producers and retailers anxious to throw off the yoke of government regulation, the OPA was at the center of post-war discussions about the future of the American economy. Given today's cost of living problems, I find it fascinating to study the economics of the first half of the 20th century, and how societal reactions and government policies continue to shape today's discussions about the future of our economy - whether people realize it or not. Today, economists are studying the impact of the Great Recession and COVID-19 on our economic future, just like historians and economists in the 1920s and 1940s did when they were looking back at the two World Wars. Further Reading

If you enjoyed this blog post, consider supporting The Food Historian on Patreon! Patrons get special perks, including members-only content, access to digitized cookbooks, and occasional snail mail. Patrons also help keep this blog free for everyone. Join today! Rice is one of the world's oldest cultivated crops. Domesticated in China as many as 15,000 years ago, trade routes helped spread this grain across the ancient world. Rice has many different uses, but porridge-y things, from congee to rice pudding, seem common in cultures around the world. Although Americans may be most familiar with Asian "white rice" and "brown rice," there are actually hundreds of different varieties. In fact, the first rice to be cultivated in the United States was actually an African variety. The development of rice plantations in the American South is a direct result of skilled labor and knowledge by enslaved Africans exploited by the people who enslaved them. South Carolina and Georgia in particular were some of the few places in North America where rice was grown commercially until the later 19th century, when rice spread to Louisiana and Texas. In the early 20th century, Arkansas and California followed suit. Today, Southern states still grow Carolina varieties of African rice, while California focuses more on japonica varieties of Asian rice, likely influenced by Chinese immigration during the Gold Rush of the 1840s and after. Early recipes for rice pudding included cooking it in a pie crust, baking it with just butter and milk, or in a custard. In the U.K., a short-grained "pudding rice" is most often used to make rice pudding. In the U.S., Americans tend to use long grain white rice varieties. You don't find rice pudding too often these days. Usually relegated to nursing homes and hospitals, you'll occasionally find it on restaurant (or especially New York deli) menus. But I think rice pudding deserves a revival. When life has you down, nothing tastes more comforting and nourishing than homemade rice pudding. But rice pudding can be finicky stuff to make. I don't know when I discovered the idea for this genius recipe, but I'm sure it was somewhere on the internet about ten years ago. This recipe couldn't be easier, and it's the only one I ever use. No eggs, no custard, no baking, one pot and done. So simple. As a Scandinavian, rice pudding is in my blood. This one is a cross between the traditional Norwegian kind, served hot and cinnamon-y at Christmas, with a lucky almond in someone's bowl resulting in a marzipan pig, and the Swedish kind I grew up eating at midsommar - cold, creamy, and with raspberries on top. It's good hot or cold, with or without milk or cream or whipped cream. It's one of my favorite comfort recipes, and I hope you enjoy it, too. Easy Rice PuddingThe genius of this recipe comes from the substitution of arborio or risotto rice for regular white rice. The arborio rice thickens the milk as it cooks, creating a creamy, sweet deliciousness that's in the rice to the core. I can't take credit for discovering it, and the American who came up with it was probably inspired by the "pudding rice" of the U.K., but it's too easy and delicious not to share. This recipe does bear a little watching, as milk is quick to boil over, but make it while you're doing dishes, baking something, or otherwise puttering around in the kitchen. 1 cup arborio rice 5-6 cups whole milk (or milk of your choice) 1/2 cup sugar 1 cinnamon stick about 1 cup raisins (I used half Thompson and half golden) Place all ingredients in a 4 or 5 quart stock pot and cook over medium to medium-high heat until the milk comes to a boil (watch it so it doesn't boil over!). Then reduce the heat to medium low and cook, stirring frequently, until most of the milk is absorbed. When it's still a bit soupy, turn the heat off and let the rice rest. It will absorb more milk as it sits. Serve hot for breakfast or warm or cold for dessert. It keeps well in the fridge, but the rice will absorb milk, so if it gets too thick, add a little milk to thin. If you don't have a cinnamon stick, a sprinkling of ground cinnamon is fine. If you'd rather leave out the raisins, feel free! Add dried cranberries, blueberries, or serve with fresh or frozen strawberries or raspberries. You could also flavor with orange or lemon zest, nutmeg, almond or vanilla extract, or any other flavorings you enjoy. Do you have a favorite creamy dessert? A favorite way to eat rice pudding? I must admit that while this recipe is very good, it's not quite as good as the Swedish rice pudding I grew up eating, which was VERY creamy, sweet, and served cold with thawed frozen sweetened raspberries with their juice. I would stir it to turn the rice pudding purple and make sure I got raspberries in every bite. Alas, the only recipe I have for that makes gallons, so I've never tried it.

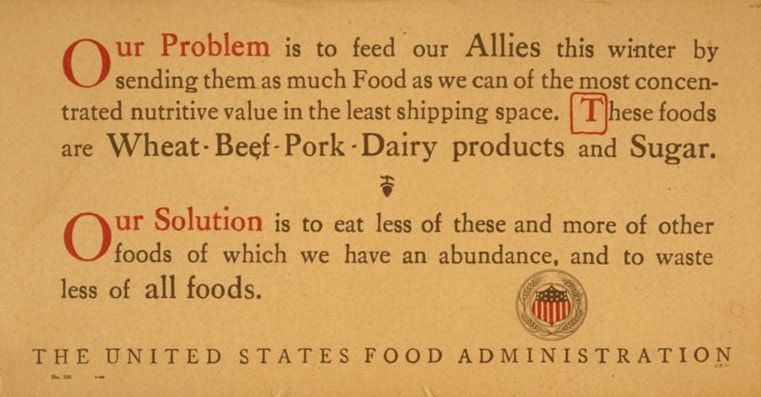

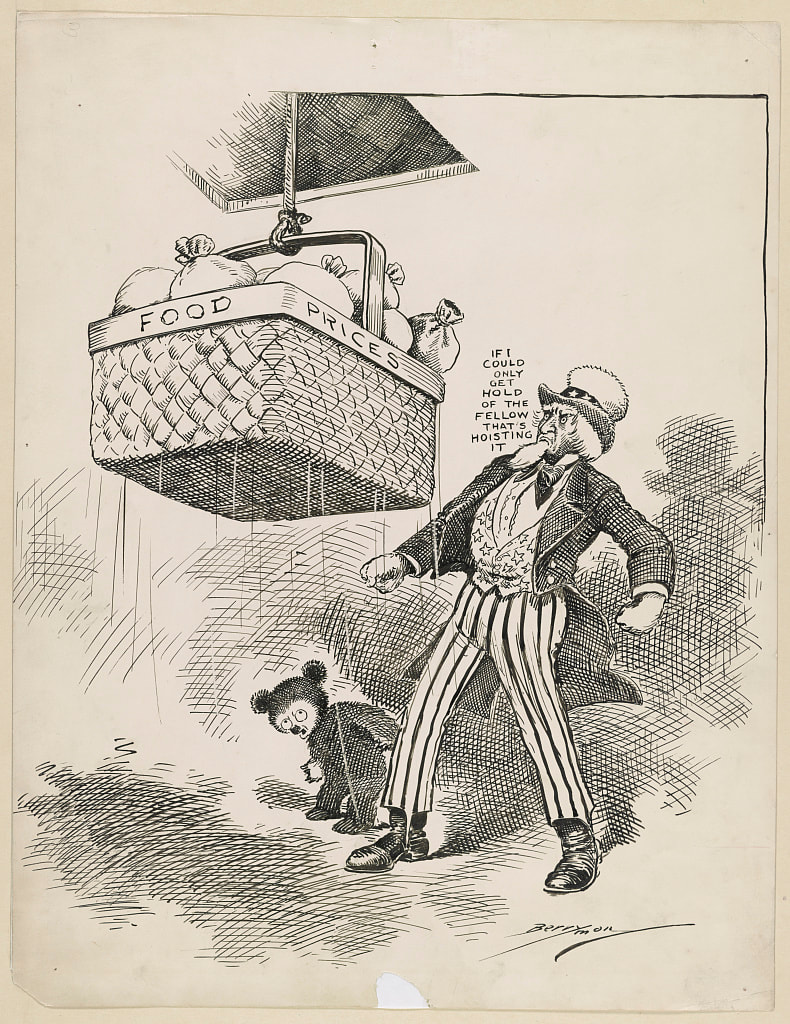

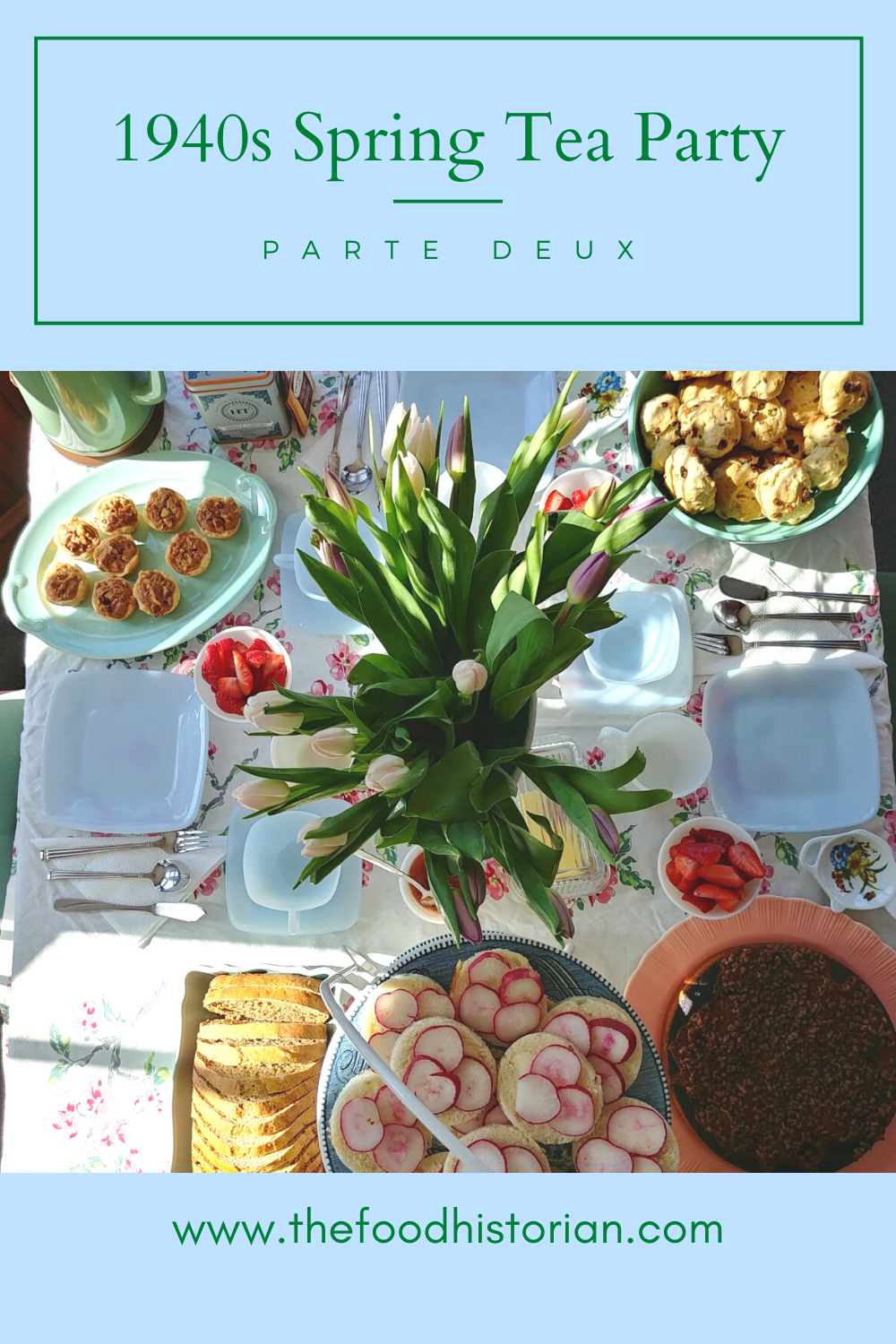

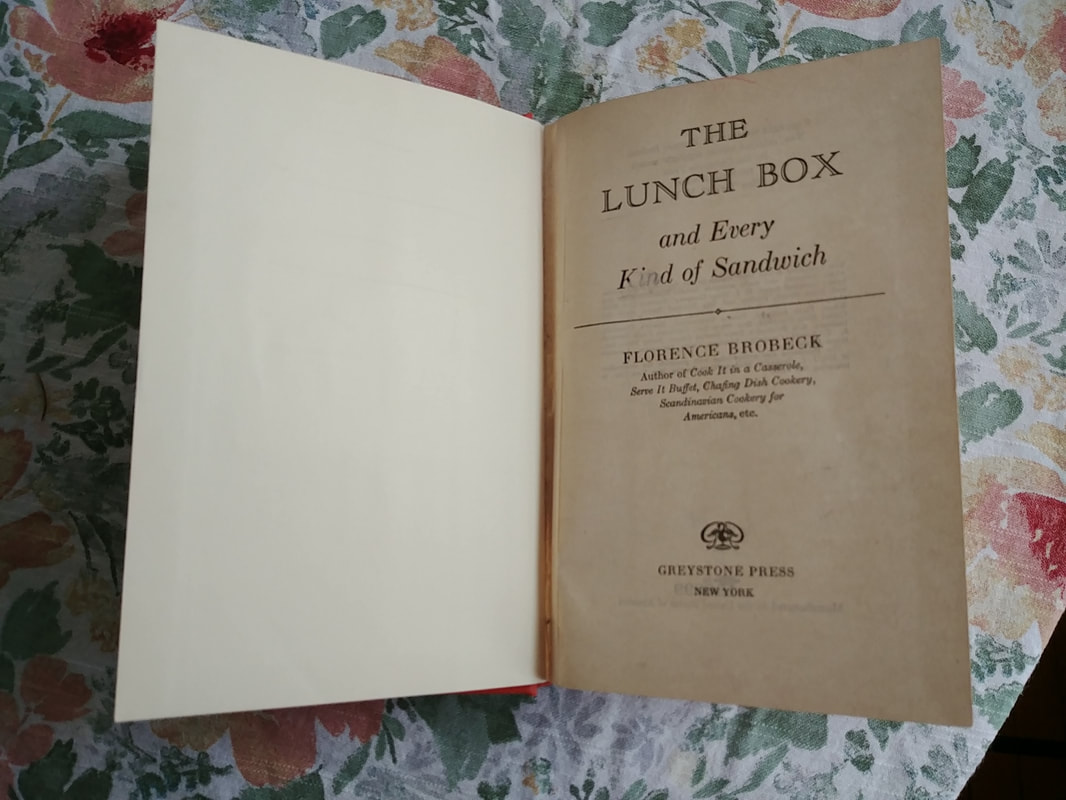

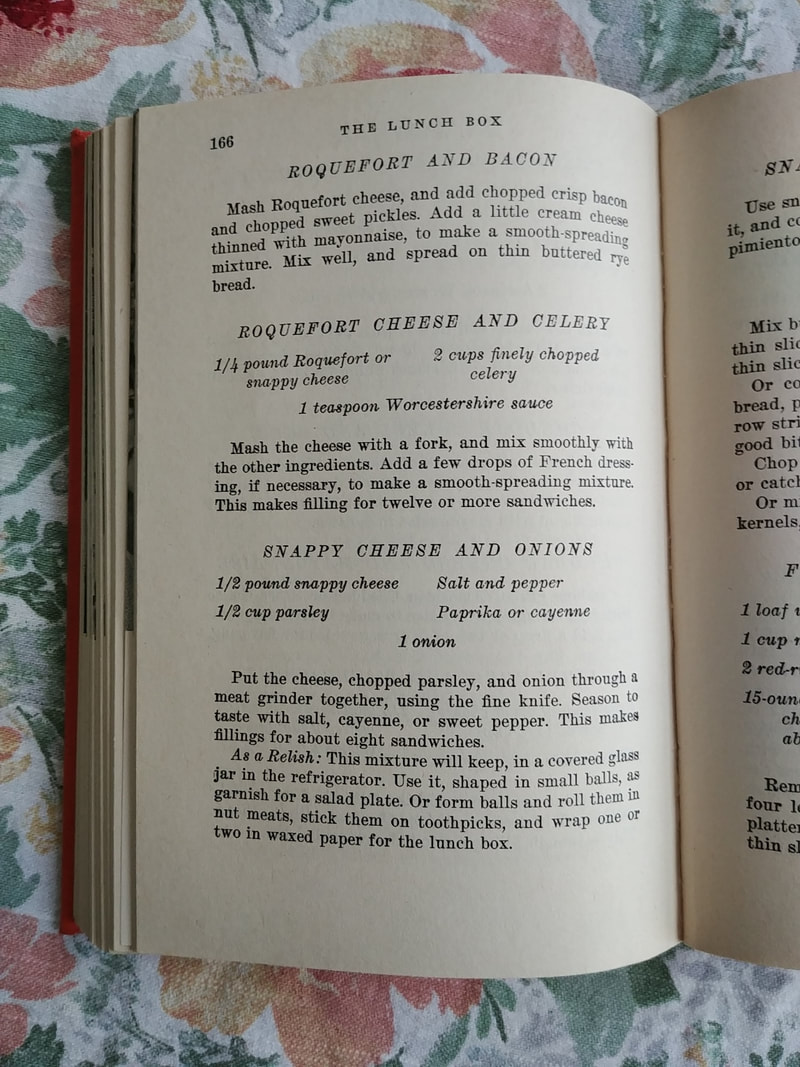

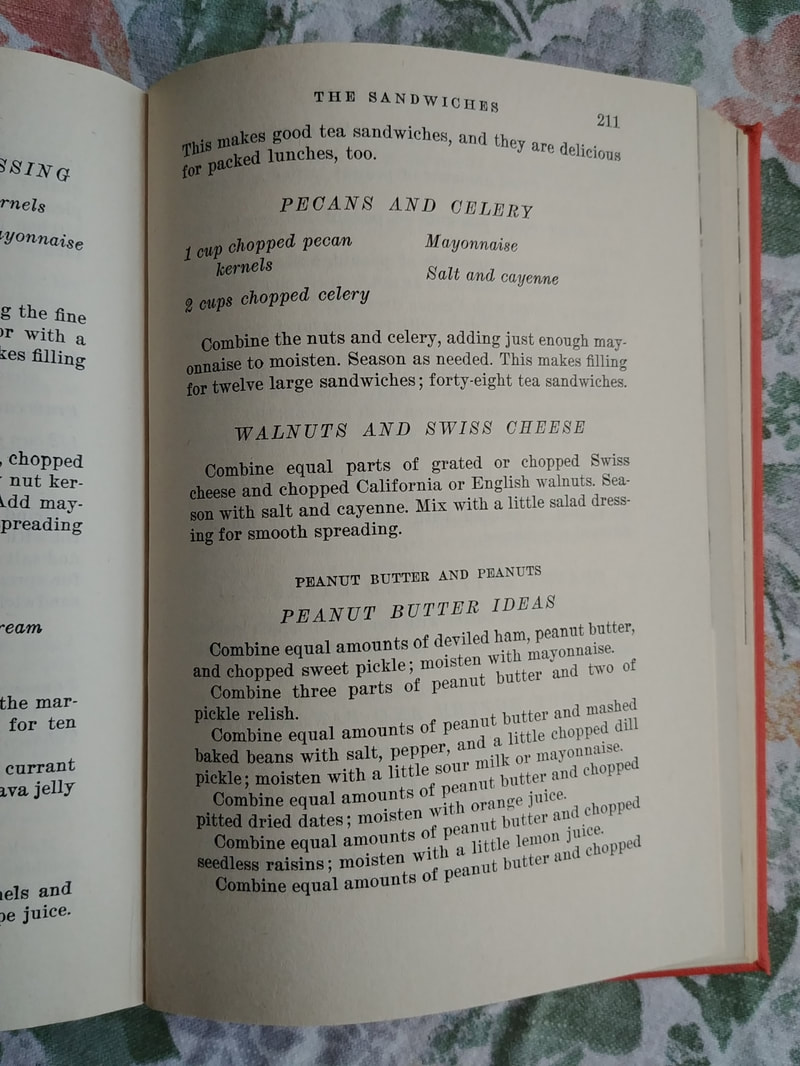

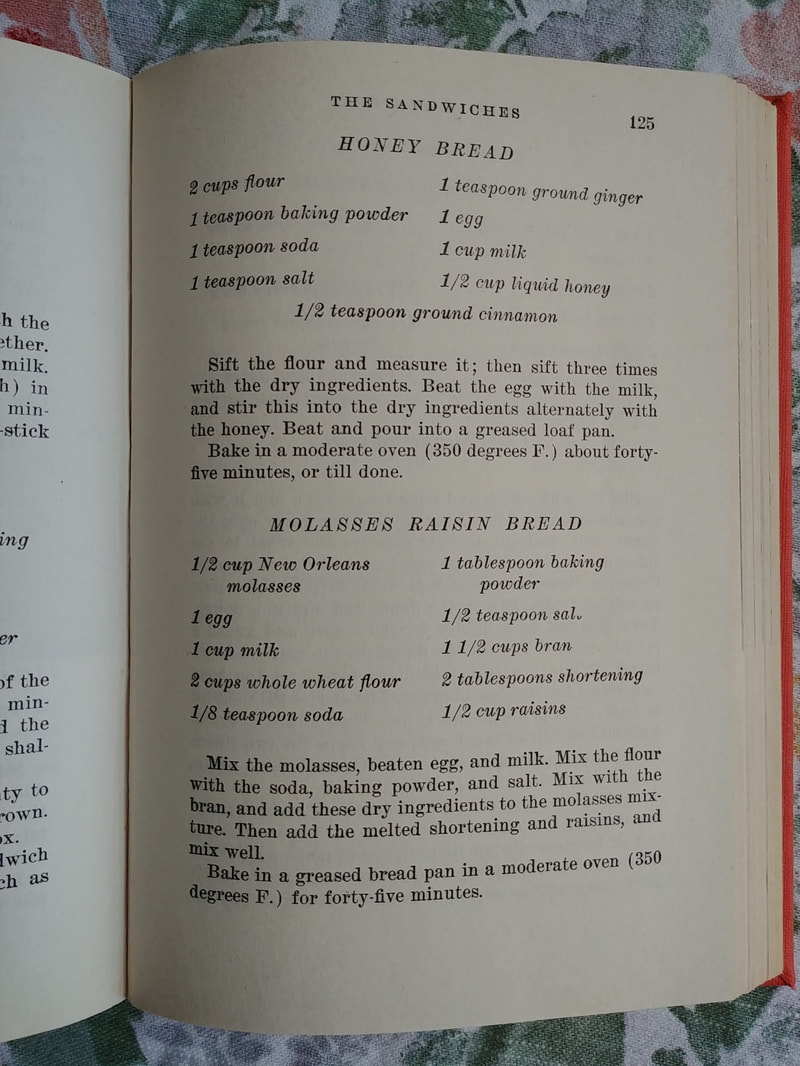

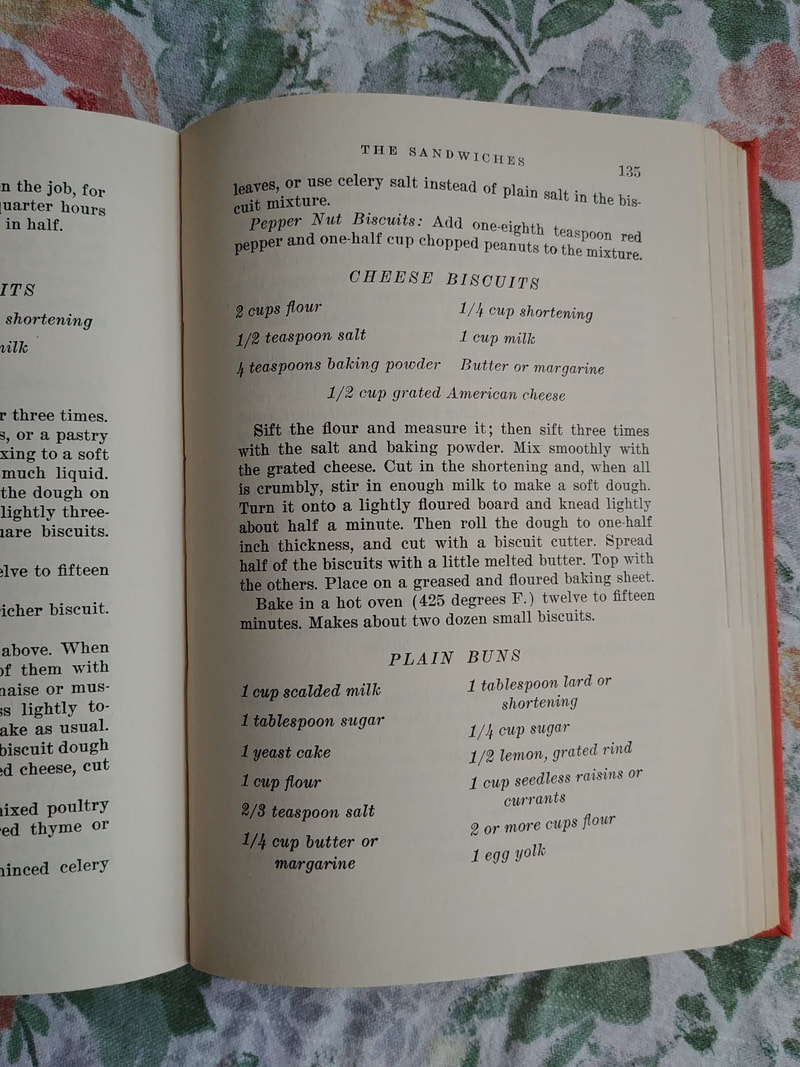

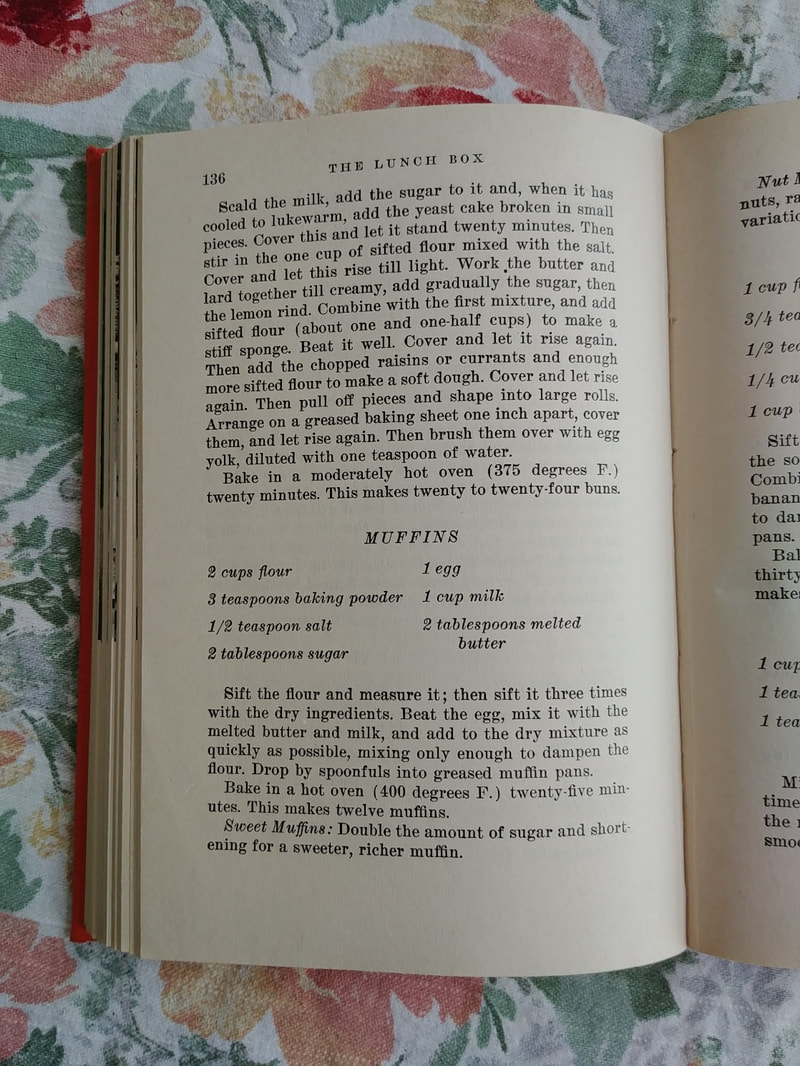

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Even though the United States didn't officially join the war until April 7, 1917, the U.S. had long supported the Allies and neutral nations through the sale of agricultural products. But the 1910s was a time of little government regulation and increasingly global commerce. The Allied European nations all leaned heavily on their colonial holdings to produce food and war materiel, what goods they could get through German U-boat blockades. Part of the reason for German expansionism in Europe was a lack of colonial holdings (also the reason for the Second World War, as ably argued by Lizzie Collingham in The Taste of War), and therefore a lack of agricultural capacity. As an independent nation rich in natural resources (through their own brutal colonization of the continent), the United States was able to meet the increasing European demand. Midwestern wheat farmers in particular were very happy, as the increased demand increased prices. But while farmers were happy to have good return on their crops, the increased demand from abroad was increasing food prices at home. The High Cost of Living or "H.C.L." as it was often referred to in the press, was the topic of much discussion throughout the Progressive Era. Kosher meat riots in 1902 and again in 1910 in New York City were only the beginning. Exacerbated by the war, by 1917 rising food prices led women around the world to riot against food prices that increased sometimes 200% in a matter of weeks. You can read more about the food riots of New York City in a previous blog post. In this image (hard to tell if it was used as a political cartoon or a poster), Uncle Sam looks at a picnic basket labeled "Food Prices" being hauled up through the ceiling. He mutters to himself, "If only I could get hold of the fellow that's hoisting it." His fists are at his side, impotently, while a small teddy bear (whose significance is unclear, but may have been a reference to Teddy Roosevelt --- see the update below!) looks on in dismay. The image reinforced the idea that the federal government had little or no control over food prices. Ultimately, the food price question was never really settled. Boycotts temporarily created surpluses, which lowered prices. But only the increased wartime production when the U.S. entered the war in 1917 seemed to raise wages and increase agricultural supply enough to address rising food prices. And when the war ended in late 1918, food prices increased again as regulating government agencies like the United States Food Administration were dismantled, but relief efforts abroad continued, along with the supply of the American Expeditionary Forces, many of whom did not return until the end of 1919 or even later. Increased production encouraged during the war years resulted in an agricultural depression in the 1920s, as European nations recovered their own agricultural production and demand for American exports fell. The agricultural depression was an early harbinger of the Great Depression. Stay tuned next week for propaganda about the High Cost of Living during the Second World War. UPDATE: Many thanks to Food Historian reader Peter K. for giving us some more context about the teddy bear! Apparently artist Clifford Berryman was the originator of the Teddy Bear, which was indeed inspired by Theodore Roosevelt. Adding the teddy bear to various political cartoons was one of Berryman's signatures, although the bear was often the star of the show. Once Teddy Roosevelt left office, Berryman also used the bear to represent his own opinions in political cartoons. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! I've spent the last several weeks packing up one room after another in my house, having it painted, and then unpacking. It's been quite a tedious chore, and I must admit, I left the worst for last - my office/guest bedroom which houses my cookbook library! So a friend came over to help me pack up my fragile historic cookbooks and move bookshelves (among other things), so we started our day with a little tea party lunch. We had deviled eggs, spring pea "hummus" sandwiches, oatmeal nutmeg scones with butter and strawberry jam, and plenty of tea with sugar and milk. You can find my favorite deviled egg recipe and oatmeal nutmeg scone recipe here, but the spring pea "hummus" is new, so I thought I would share it as a nice, springy, Meatless Monday recipe. It's not historic in the least - it's my own creation - although it does FEEL like someone in the 1940s would have thought of this as a sandwich spread. Spring Pea HummusIf you want to keep the green color, you need an acid to prevent the peas from turning olive green. Yogurt, buttermilk, lemon juice, or vinegar will all help keep that vibrant green. Fair warning - this makes a lot! Close to a quart. So cut the recipe in half if you live in a small household. 1 bag frozen peas 1/4 cup salted, roasted almonds 3 scallions 1/2 cup cottage cheese 1 tablespoon (or more) lemon juice salt & pepper to taste Bring about about an inch of water to boil in a 2 quart saucepan with a lid, then add the peas and steam, covered for 2 or 3 minutes, until they are tender and bright green. Drain and rinse in several changes of cold water to stop the cooking (and preserve the color). In a food processor or chopper, add all the ingredients, with the scallions and almonds in the bottom, so they blend first and best. Pulse until well-blended. Add a little water or more lemon juice to taste. This is a very forgiving recipe, and will take substitutions easily, provided the peas stay. Substitute walnuts or pumpkin seeds for the almonds, or leave the nuts out altogether (they do give some body). Substitute yogurt or sour cream or even a little buttermilk, or even avocado for the cottage cheese. Use vinegar instead of lemon juice, garlic or raw onion or chives instead of scallions. Add spinach or fresh parsley or dill for extra color and flavor. I served this spread on toasted rye bread, but you can serve it on any kind of bread, or crackers, or flatbread, or potato chips, or with vegetables, or roll it up inside thinly sliced salami, or a piece of cheese. Use it as an addition to a BLT (you can leave out the T, if you're so inclined), or a ham or turkey sandwich. Put pickled onions on top or dollop it on a baked potato, or both. Stir it into hot pasta with some chicken and roasted spring vegetables for a yummy pasta primavera. The possibilities are endless! Let's be honest, the scones and deviled eggs are just about gone, but the spring pea hummus will be making several showings this week for lunch. It's a nice way to get an extra, and yummy, serving of vegetables in. I hope you enjoy it! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!  “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf, not the farmer of the United States who works and sacrifices to fill the holds of victory ships…,” says the narrator as an oversized silhouetted farmer pours grain into the hold of a ship. Still from the film "Food Will Win the War" (1942). Courtesy Cartoonresearch.com Previously, we met Jack Sprat and his wife in a fairytale cartoon propaganda poster. This week, we go all out total war with Walt Disney. Produced by Disney in 1942, "Food Will Win the War" was a propaganda film of the Agricultural Marketing Administration, under the auspices of the United States Department of Agriculture. Narrated like a newsreel, the cartoon illustrates the might of American agriculture, in brilliant technicolor. The cartoon illustrations of the overwhelming productivity of American agriculture compare mind-boggling production numbers to well-known landmarks and other Very Large Things. Flour to blizzards, bread to the Egyptian pyramids, tomatoes to the Rock of Gibraltar, cheese to the moon, etc. When getting to meat production, we get to see the Disney's Three Little Pigs, leading a parade of hundreds of hogs, playing "Who's Afraid of the Big, Bad Wolf?" on fife and drum. Periodically, we are reminded that the size of several of these items could crush Berlin, including a very plump blonde representing American fat and oil production. One scene compares American agriculture to a giant bowling ball, which is depicted rolling through Nazi headquarters (tattering the Nazi flag in the process), and bowling over pins caricaturing Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Emperor Hirohito. The film closes with a grim montage of the challenges faced by shipping and a call to the Four Freedoms outlined by FDR - Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. Like many propaganda films and newsreels from World War II, this one has plenty of bombast, with good and evil portrayed in stark black and white terms (even though the animation is in color). Released to American audiences on July 21, 1942, it had several goals. One was to buoy American confidence in food supplies. There were concerns that the U.S. was shipping too much produce overseas and that there would be shortages at home. These concerns were not unfounded, but wartime production increased enough that even though rationing eventually grew tight, everyone had enough to eat. Another was to impress upon foreign audiences that American production capacity was overwhelming and would strengthen the Allies, who had been at war for over two years already. In 1941, Disney was suffering major financial losses from Fantasia - it was a box office flop and made just a fraction of what it cost to produce. You can see the economy of animation in many of the scenes of this film - where largely still images move across the frame or zoom in or out - achieved by layering cells. But the success of Disney's animated films for the war effort helped keep the studio afloat during the war. They became well-known in particular for training films, as Disney animators were able to illustrate in fine detail mechanical operations and theoretical scenarios that would be difficult or impossible to film in real life. Some speculate that without World War II, Disney Studios might have gone under after only a few films. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Some of you may have looked askance at the last episode of Food History Happy Hour where I made (or rather, botched) the 1902 Irish Cocktail. In my defense, it has been a long and rather sleep-deprived spring, and so I let my determination to do the cocktail outweigh my lack of alcohol knowledge, to rather disastrous results. The lesson? You can probably substitute one ingredient in a cocktail, but two or three is a bridge too far. However, Food Historian friend (and Patreon patron!) Anna Katherine is actually an oenologist (that is, a wine scientist) and knows a great deal more about alcohol than I do. She clearly also has a much better stocked liquor cabinet. So she revisited the original recipe much more faithfully, and found the results much better. Here's what she has to say: [A]s a general rule I don't criticize another scholar's work, but after that...er... creation you produced Friday I had Questions. (And a healthy dose of Professional Curiosity.) So- substituting only Pernod for Absinthe, I made the Irish Cocktail. I agree with your estimation of 2oz for a small wine glass, and a dash is a scant 1/4th tsp. I also shook instead of pouring over shaved ice, because I didn't have any- but I compensated by shaking a bit longer than usual to get some melt into the drink, as would happen as you sipped something over shaved ice. The result was perfectly pleasant- a bit boozy, yes, but the dashes of Pernod, curaçao and maraschino added a touch of sweetness that brought out the vanilla notes in the curacao and whiskey, and added some subtle, complex spice around the edges of an otherwise straightforward drink. The lemon peel brought pulled the balance back in so it was focused instead of fat and sweet. Whiskey (made from malt and aged in old barrels) is more subtle and less oaky than bourbon (made from corn and aged in new barrels), so I suspect I had a softer, more integrated, and more balanced tipple than your alcoholic anise Shirley Temple. (I forgot the olive. Dammit.) I never shirk from constructive criticism! Although it must be noted that Anna Katherine did technically substitute Cointreau for curaçao, even though some argue that Cointreau is just a version of curaçao, it is not generally labeled as such in liquor stores, so poor novices like me can't be blamed for buying the blue stuff, okay? ;) Thankfully, we both agreed that the addition of an olive (the original recipe does not indicate ripe, Spanish, or pimento-stuffed) was a strange addition, anyway. You can check the original post for the historic recipe, but Anna Katherine followed it pretty faithfully, except for the substitution of Pernod for the absinthe, which is much-maligned in history, as this excellent article outlines, but which is now "legal" again in the United States, although difficult to find on liquor store shelves. Absinthe, of course, is chartreuse in color, but the recipe contains so little of it one wonders if it would have affected the color of the cocktail at all. Certainly the curaçao would not have been blue at that time, as the best guesses are it was tinted blue starting in the 1920s. Many thanks again to Anna Katherine for taking on the task of trying a more accurate version of the recipe and reporting back the results! Is your liquor cabinet well-stocked enough to try the Irish Cocktail? Do you think the olive would add anything? Let us know in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!  This World War I cartoon shows a hand in a gauntlet (decorated with the imperial German eagle) carving up a map of the Southwestern United States. Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas are labeled "For Mexico." California is labeled "For Japan(?)" The rest of the country is labeled "For Myself." In the spring of 1917, the British government intercepted and turned over to the United States a message from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmerman to the Government of Mexico, urging Mexico to join with Japan and declare war on the United States. Zimmerman suggested that this would be a way for Mexico to reclaim the Southwestern states lost during the Mexican War. American outrage following the publication of the Zimmerman Telegram was one of the factors causing the U.S. to declare war on Germany. Berryman follows the popular notion that the German Kaiser was the force behind German aggression. Illustration by Clifford Kennedy Berryman, March 4, 1917. Library of Congress. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson, the man who had won his 1916 presidential reelection by running on the phrase, "He Kept Us Out of War," went before Congress and gave a speech. It was a speech a long time coming. Since Europe had devolved into war in August of 1914, the United States had officially remained neutral. On May 7, 1915, the Lusitania was sunk, the victim of German U-Boats, taking 123 American citizens with it. Despite this attack on innocent civilians, the U.S. remained staunchly neutral. In February, 1917, the Zimmerman Telegram was revealed - an appeal by Germany to Mexico to form an alliance against the United States, should the U.S. enter the war. Sent in January and decrypted by British Intelligence, it was sent just before Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, a tactic they feared would result in the end of American neutrality. And indeed, it did. Unrestricted submarine warfare resumed on February 1, 1917. Wilson gave a speech before Congress on February 3rd, and then again on February 26th regarding U-boats and merchant shipping. On April 2nd, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. I have called the Congress into extraordinary session because there are serious, very serious, choices of policy to be made, and made immediately, which it was neither right nor constitutionally permissible that I should assume the responsibility of making. On the 3rd of February last, I officially laid before you the extraordinary announcement of the Imperial German government that on and after the 1st day of February it was its purpose to put aside all restraints of law or of humanity and use its submarines to sink every vessel that sought to approach either the ports of Great Britain and Ireland or the western coasts of Europe or any of the ports controlled by the enemies of Germany within the Mediterranean. That had seemed to be the object of the German submarine warfare earlier in the war, but since April of last year the Imperial government had somewhat restrained the commanders of its undersea craft in conformity with its promise then given to us that passenger boats should not be sunk and that due warning would be given to all other vessels which its submarines might seek to destroy, when no resistance was offered or escape attempted, and care taken that their crews were given at least a fair chance to save their lives in their open boats. The precautions taken were meager and haphazard enough, as was proved in distressing instance after instance in the progress of the cruel and unmanly business, but a certain degree of restraint was observed. The new policy has swept every restriction aside. Vessels of every kind, whatever their flag, their character, their cargo, their destination, their errand, have been ruthlessly sent to the bottom without warning and without thought of help or mercy for those on board, the vessels of friendly neutrals along with those of belligerents. Even hospital ships and ships carrying relief to the sorely bereaved and stricken people of Belgium, though the latter were provided with safe conduct through the proscribed areas by the German government itself and were distinguished by unmistakable marks of identity, have been sunk with the same reckless lack of compassion or of principle. (read the whole speech) On April 4, 1917, the Senate voted to declare war. On April 6, the House of Representatives followed suit. The U.S. was now officially at war with Germany.  "Our Problem is to feed our Allies this winter by sending them as much Food as we can of the most concentrated nutritive value in the least shipping space. These foods are Wheat - Beef - Pork - Dairy products and Sugar. Our Solution is to eat less of these and more of other foods which we have in abundance, and to waste less of all foods. The United States Food Administration." c. 1917, Library of Congress. On April 17, 1917, Wilson addressed the nation: I take the liberty, therefore, of addressing this word to the farmers of the country and to all who work on the farms: The supreme need of our own nation and of the nations with which we are coordinating is an abundance of supplies, and especially of food-stuffs. The importance of an adequate food supply, especially for the present year, is superlative. Without abundant food, alike for the armies and the peoples now at war, the whole great enterprise upon which we have embarked will break down and fail. The world's food reserves are low. Not only during the present emergency but for some time after peace shall have come both our own people and a large proportion of the people of Europe must rely upon the harvests in America. Upon the farmers of this country, therefore, in large measure, rests the fate of the war and the fate of the nations. May the nation not count upon them to omit no step that will increase the production of their land or that will bring about the most effectual coordination in the sale and distribution of their products? The time is short. It is of the most imperative importance that everything possible be done and done immediately to make sure of large harvests. I call upon young men and old alike and upon the able-bodied boys of the land to accept and act upon this duty to turn in hosts to the farms and make certain that no pains and no labor is lacking in this great matter. I particularly appeal to the farmers of the South to plant abundant food-stuffs as well as cotton. They can show their patriotism in no better or more convincing way than by resisting the great temptation of the present price of cotton and helping, helping upon a great scale, to feed the nation and the peoples everywhere who are fighting for their liberties and for our own. The variety of their crops will be the visible measure of their comprehension of their national duty. The Government of the United States and the governments of the several States stand ready to coordinate. They will do everything possible to assist farmers in securing an adequate supply of seed, an adequate force of laborers when they are most needed, at harvest time, and the means of expediting shipments of fertilizers and farm machinery, as well as of the crops themselves when harvested. The course of trade shall be as unhampered as it is possible to make it and there shall be no unwarranted manipulation of the nation's food supply by those who handle it on its way to the consumer. This is our opportunity to demonstrate the efficiency of a great Democracy and we shall not fall short of it! This let me say to the middlemen of every sort, whether they are handling our food-stuffs or our raw materials of manufacture or the products of our mills and factories: The eyes of the country will be especially upon you. This is your opportunity for signal service, efficient and disinterested. The country expects you, as it expects all others, to forego unusual profits, to organize and expedite shipments of supplies of every kind, but especially of food, with an eye to the service you are rendering and in the spirit of those who enlist in the ranks, for their people, not for themselves. I shall confidently expect you to deserve and win the confidence of people of every sort and station. (read the entire speech) Wilson's emphasis on food was not without warrant. The U.S. and Argentina, the two major wheat-exporting countries in the Western hemisphere (excepting Canada), had both experienced poor harvests in 1916, after bumper crops in 1914 and 1915. In short, when the U.S. entered the war in April of 1917, it had only enough wheat for domestic consumption. Although the initial rollout of food regulation was uneven, in large part due to the fact that Congress blocked funding of the United States Food Administration until August of 1917, calls for voluntary reduction in consumption of certain foods, like those listed in the poster above, were almost immediate, as were calls to reduce food waste and increase food production. Wilson knew that defeating German aggression meant putting the United States' abundant resources to work - agricultural land, people, and industry. As with all wars, he who controls the food supply, controls the outcome of the war, something that proved true with the First World War as much as any war, and one in which the United States made a huge difference. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Spring has sprung, with daffodils nodding in the frosty air and trees starting to bud out. So it seemed apt to celebrate with another tea party! Once again, our tiny tea party with just one friend featured all-vegetarian recipes, since said friend is a vegetarian. And also because chicken salad, while delicious, seems lazy when you're looking for something new and interesting to try. This one featured recipes from a new cookbook acquisition, The Lunch Box and Every Kind of Sandwich by Florence Brobeck. My edition was published in 1949, although I believe the original was published sometime in the 1930s. It's also a bright orange library binding without the original dust jacket. So no pretty cover to show off this time! Unlike last time, my ambitious list didn't go QUITE as planned. Adapting historic recipes can be like that. 1940s Spring Tea Party MenuOpen-Faced Radish and Butter Sandwiches on White Open-Faced Cucumber and Cream Cheese Sandwiches on Rye Blue Cheese, Pecan, and Celery Sandwiches on Whole Grain 1940s Whole Wheat Honey Quick Loaf 1940s "Plain Buns" with Butter and Jam Fresh Sugared Strawberries Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake Walnut Tassies Hot Cocoa Tea with Cream and Sugar The SandwichesRadish and butter sandwiches just scream spring to me, and they're very easy to put together. To make things extra fancy, cut sliced bakery bread (not the squishy kind from the bread aisle - hit the bakery and get peasant, sourdough, brioche, or in a pinch, French or Italian bread) with a cookie or biscuit cutter into rounds. Spread with soft butter, top with thinly sliced radishes, and a sprinkling of salt (I used pink Himalayan). The salt is what makes the radishes look wet, but adds a nice flavor. Open-faced cucumber sandwiches are equally easy. Make a cream cheese spread with softened cream cheese (15 seconds in the microwave does the trick), and thinly sliced scallions and dried dill. You can use jarred garlic or minced sweet onion instead of scallions. Spread it on any kind of rye bread. Top with English (a.k.a. seedless - even though they're not - or burpless) cucumbers. If you're hungry, top with another slice of bread spread with the cream cheese mixture, otherwise serve open-faced (which is prettier and more Scandinavian). If you're going really fancy, use fresh dill in the cream cheese and top each sandwich with a sprig of fresh dill. The little square sandwiches were a mashup of two recipes from the The Lunch Box - "Roquefort Cheese and Celery" and "Pecan and Celery" fillings. I decided to mash them up - literally - into one, slightly more interesting filling. I mixed a quarter pound of very soft blue cheese with about a cup each of diced pecans and finely minced celery, with a splash of Worcestershire sauce. It was a curious mixture. Next time I would probably add cream cheese to temper the blue cheese a little, and maybe add some scallions and/or smoked paprika. But otherwise it was quite nice on squares of thinly sliced whole grain bakery bread. Half the fun of tea sandwiches is the fun and dainty shapes you create. I always find it easier to slice the bread first, and then fill, but some people do it the other way around. Whole Wheat Honey Quick LoafWhen one encounters a recipe entitled "Honey Bread," one expects it to taste of, well, honey. Instead, the spicing of this little quick bread leaves the impression of gingerbread more than honey. Curiously, the recipe also contains no fat. I was skeptical, but aside from an accidental overbaking (which I think dried it out), it turned out fairly decently, if scarcely tasting of honey. I followed this recipe pretty much to the letter. It makes a tall loaf with a springy crumb - not at all the crumbly, moist, cake-like texture we come to associate with most quick breads today. Much more like true bread texture than cake. Here's the original recipe: 2 cups flour (I used white whole wheat) 1 teaspoon baking powder 1 teaspoon soda 1 teaspoon salt 1 teaspoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon 1 egg 1 cup milk 1/2 cup liquid honey Sift the flour and measure it; then sift three times with the dry ingredients (or if you're lazy, just whisk everything together). Beat the egg with the milk, and stir this into the dry ingredients alternately with the honey. Beat and pour into a greased loaf pan. Bake in a moderate oven (350 degrees F.) about forty-five minutes or until done. Tip out of the pan and cool on a rack. Serve with salted butter, honey butter, and/or jam. 1940s "Plain Buns"This recipe is deceptive. The title, "Plain Buns" is not accurate - flavored with lemon zest and currants (I used golden raisins), the flavor was surprisingly strong and delicious. Designed to be used with cake yeast, all I had was rapid rise yeast, so I think they got a little overproofed. I'm going to try making them with active dry yeast again, so I won't comment too much on what I did, and just give you the original recipe: 1 cup scalded milk 1 tablespoon sugar 1 yeast cake 1 cup flour 2/3 teaspoon salt 1/4 cup butter or margarine 1 tablespoon lard or shortening 1/4 cup sugar 1/2 lemon, grated rind 1 cup seedless raisins or currants (I used golden raisins) 2 or more cups flour 1 egg yolk Scald the milk, add the sugar to it and, when it has cooled to lukewarm, add the yeast cake broken into small pieces. Cover this and let it stand twenty minutes. Then stir in one cup of sifted flour mixed with the salt. Cover and let this rise until light. Work the butter and lard together until creamy, add gradually the sugar, then the lemon rind. Combine with the first mixture, add the sifted flour (about one and one-half cups) to make a stiff sponge. Beat it well. Cover and let it rise again. Then add chopped raisins or currants and enough more sifted flour to make a soft dough. Cover and let rise again. Then pull off pieces and shape into large rolls. Arrange on a greased baking sheet one inch apart, cover them, and let rise again. Then brush them over with egg yolk, diluted with one teaspoon of water. Bake in a moderately hot oven (375 degrees F.) twenty minutes. This makes twenty to twenty-four buns. Obviously I didn't let rapid rise yeast go through fours separate rises! But I think it still overproofed a bit. I also forgot the egg wash! Which meant the buns looked a bit more like rocks. But they sure tasted good, and that's what mattered. If you enjoy the citrusy flavor of hot crossed buns, you'll love these. Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake & Walnut TassiesI've made Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake before, but this time I was somehow out of coconut, so I used chopped pecans for the topping as chopped nuts are the other traditional topping ingredient. Not QUITE as good as the coconut, but still yummy. Sadly for you, I did not make the walnut tassies (my friend did), and thus cannot share the recipe. However, she, like I did, had to make some substitutions! For Walnut Tassies are supposed to be Pecan Tassies, but my friend was out of pecans, so walnuts it was. The original recipe is supposed to be like tiny pecan pies, but tiny walnut pies were equally good. One of the primary joys of tea parties, of course, is in the dishes. I've got my vintage Fire King Azurite Charm teacups and saucers, with newly acquired luncheon plates, some milk glass compotes with sugared strawberries in them, milk glass D ring mugs for cocoa, and assortment of vintage servingware in springy shades, on a vintage floral tablecloth. With tulips in the middle, of course. If you missed the last spring tea party, you can check it out here, with a promise of more to come! Have you had a tea party recently? What favorite food did you feature? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed