|

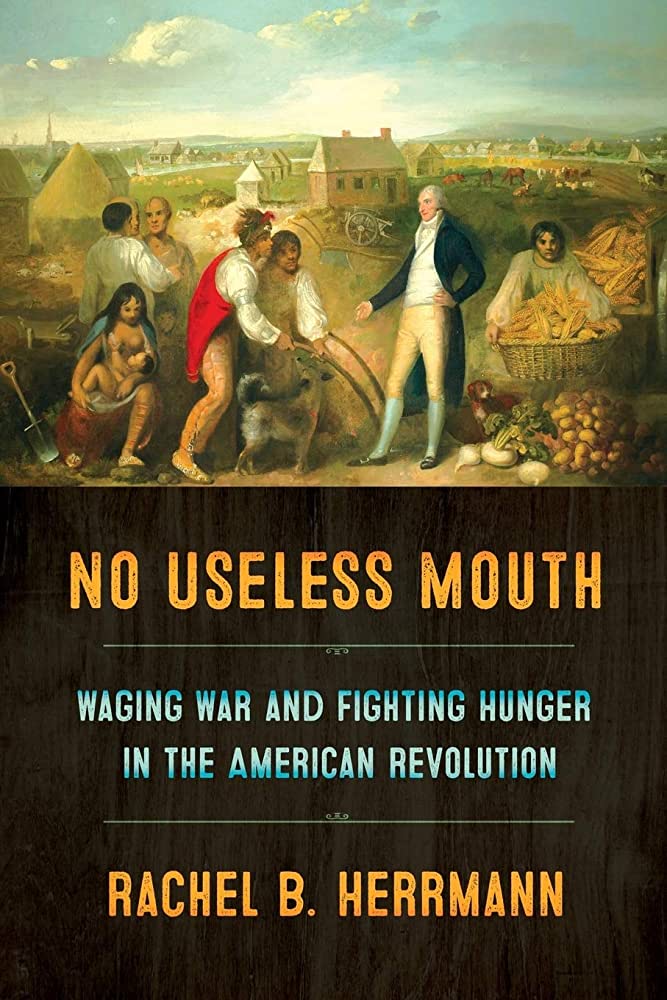

This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. This may be the longest I have ever taken to write a book review. I first received this book and the invitation to review it for the Hudson Valley Review in the fall of 2021. As many of you know, 2022 was a rough year for me, for many reasons, but I finally turned in the review in February of 2023. A few days ago, I received my copy of the Review and now that my book review is in print, I feel I can share it here! This edition of the Review is great, with several excellent articles and other book reviews, so if you manage to find a copy, please check it out! Back issues are often posted digitally. Without further ado, the review: In the historiography of the American Revolution, one can be forgiven for thinking every possible topic has been covered. But Rachel B. Herrmann’s new book No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution brings new nuance to the period. In it, Herrmann argues that food played a decisive role in the shifting power dynamics between White Europeans, Indigenous Americans, and enslaved and free Africans and people of African descent. She looks at the American Revolution through an international lens, covering from 1775 in the various colonies through to the dawning of the 19th century in Sierra Leone. The book is divided into eight chapters and three parts. Part I, “Power Rising,” introduces us to the ideas of “food diplomacy,” “victual warfare,” and “victual imperialism” within the context of the American Revolution. Contrasting the roles of the Iroquois Confederacy in the north and the Creeks and Cherokees in the South, Herrmann brings additional support to the idea that U.S. treaties with Indigenous groups should join the pantheon of diplomacy history, while centering food and food diplomacy within the context of those treaties. She also addresses how Indian Affairs agents communicated with various Indigenous groups – with varying success. Part II, “Power in Flux,” addresses the roles of people of African descent in the American Revolution, focusing primarily on Black Loyalists as they gained freedom through Dunmore’s Proclamation and the Philipsburg Proclamation. Black Loyalists fought on behalf of the British as soldiers, spies, and foraging groups, and escaped post-war to Nova Scotia with White Loyalists. Part III, “Power Waning,” summarizes what happened to Indigenous and Black groups post-war, focusing on the nascent U.S. imperialism of Indian policy and assimilation and the role food and agriculture played in attempts to control Native populations. It also argues that Black Loyalists adopted the imperialism of their British compatriots in attempts to control food in Sierra Leone, ultimately losing their power to White colonists. Part III also includes Herrmann’s conclusion chapter. No Useless Mouth is most useful to scholars of the American Revolution, providing good references to food diplomacy while also highlighting under-studied groups like Native Americans and Black Loyalists. However, lay readers may find the text difficult to process. Herrmann often makes references to groups and events with little to no context, assuming her readers are as knowledgeable as she. In addition, the author appears to conflate Indigenous groups with one another, making generalizations about food consumption patterns and agricultural practices without the context of cultural differences. In focusing on the Iroquois Confederacy and the Creeks/Cherokee, Herrmann also ignores other Native groups, despite sometimes using evidence from other Indigenous nations to support her arguments. For instance, when discussing postwar assimilation practices with the Iroquois in the north and the Creeks and Cherokee in the south (often jumping from one to another in quick succession), she cites Hendrick Aupaumut’s advice to Europeans for dealing successfully with Indigenous groups. But she fails to note that Aupaumut was neither Iroquois, Creek, nor Cherokee, but was in fact Stockbridge Mohican. The Stockbridge Mohicans were a group from Stockbridge, Massachusetts that was already Christianized prior to the outbreak of the American Revolution. They fought on the Patriot side of the war, with disastrous consequences to the Stockbridge Munsee population, and ultimately lost their lands to the people they fought to defend. Without knowledge of this nuance, readers would accept the author’s evidence at face-value. Herrmann’s strongest chapters are on the Black Loyalists, and her research into the role of food control in both Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone is groundbreaking, but even those chapters have a few curious omissions. In discussing Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, which was issued in 1775 in Virginia and targeted enslaved people held in bondage by rebels, freeing those who were willing to join the British Army. The chapter then focuses primarily on the roles of enslaved people from the American South. But Herrmann also mentions briefly the Philipsburg Proclamation, issued in 1779 in Westchester County, NY, which freed all people held in bondage by rebel enslavers who could make it to British lines. That proclamation arguably had a much larger impact on the Black Loyalist population, as it also included women, children, and those above military age, thousands of whom streamed into New York City, the primary point of evacuation to Nova Scotia. And yet, Herrmann does not mention at all enslaved people in New York and New Jersey, where slavery was still very active throughout the American Revolution and well into the 19th century. In the chapter on Nova Scotia, Herrmann also mentions that White Loyalists brought enslaved people with them, still held in bondage. Neither Dunmore’s nor the Philipsburg proclamations freed people held in bondage by Loyalists, and yet they get only a brief mention. Her chapters on Indigenous-European relations are extremely useful for other historians researching the period, but would have been improved with additional context on land use in relation to food. Herrmann often references famine, food diplomacy, and victual warfare in these chapters, without addressing the impact of land grabs and disease on the ability of Indigenous groups to feed themselves. She references, but does not fully address the need of European settlers to expand settlement into Indian Country as a motivating factor in war and postwar diplomacy. Finally, while the focus of the book is specifically on the roles of Indigenous and Black groups in the context of food and warfare, the omission of victual warfare by British and American troops and militias, especially in “foraging” and destroying foodstuffs of White civilian populations throughout the colonies seems like a missed opportunity to compare and contrast with policies and long-term impacts of victual warfare toward Indigenous groups. In all, this book is a worthy addition to the bookshelves of serious scholars of the American Revolution, especially those interested in Indigenous and Black history of this time period, but it also leaves room for future scholars to examine more closely the issues Herrmann raises. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

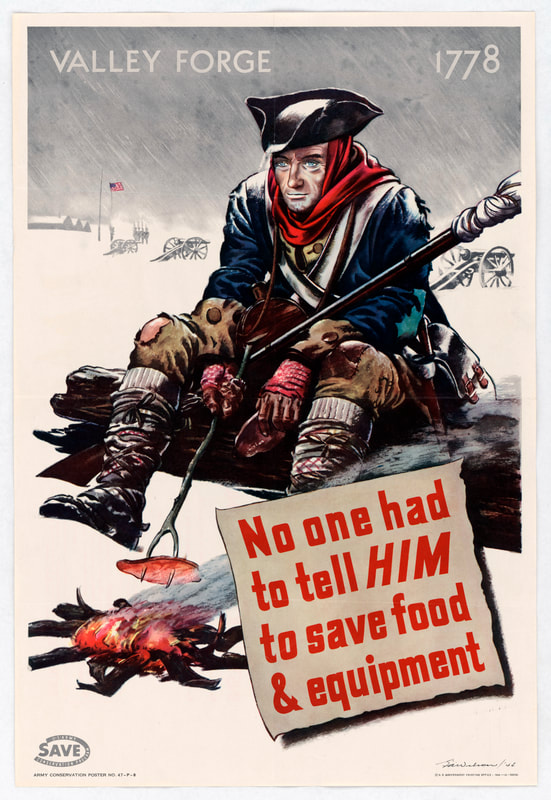

Hearkening back to the Revolutionary War was a common propaganda tactic in both World Wars. In this propaganda poster from World War II, soldiers were exhorted to save food and equipment by reminding them of Valley Forge - the winter cantonment of the Continental forces during the winter of 1777-78 which was famously (or infamously) difficult for the enlisted men, as clothing, housing, and food supplies were all very short. Despite the harsh conditions coming hard on the heels of a season of defeat against the British, General George Washington and Baron von Steuben rallied the men, beginning the formal training that would turn them into an effective force against the world's best military. In the poster image, a soldier with piercing blue eyes sits on a log next to a small campfire, enduring the falling snow. The shoulders of his blue regimental are torn, he has no greatcoat, one knee of his breeches is torn out, the other is patched. He wears a red scarf around his head and neck under his tricorned hat. The barrel of his musket is wrapped in fabric, probably to keep the snow out, and a knife or bayonet is in a sheath at his hip, next to his cartridge box. What appears to be a wooden canteen is around his neck. And on a forked stick he grills a thin piece of something over the fire - I suspect it is meant to be shoe leather, as he holds another piece in his hand, although it could simply be thin cuts of meat. The men famously boiled the leather of their shoes in an attempt to stave off starvation. What food was available was usually just meat and flour - no vegetables, no bread. These stories would have been well-known in the 1940s, part of the American mythology education that passed for history at the time. By comparing the soldiers of the American Revolution to the soldiers of the Second World War, this propaganda poster is reminding the men of the privileges they have in provisioning, and encouraging them to avoid waste, while hearkening back to the stamina and bravery of the men at the time. Other propaganda posters, like these, encouraged troops to conserve food because the folks back home were going without so they could have enough. While the nation today continues to recover from an enormous winter storm, with widespread power outages, it seemed apt to revisit Valley Forge. Read more about the food situation at Valley Forge in 1777-78. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed