|

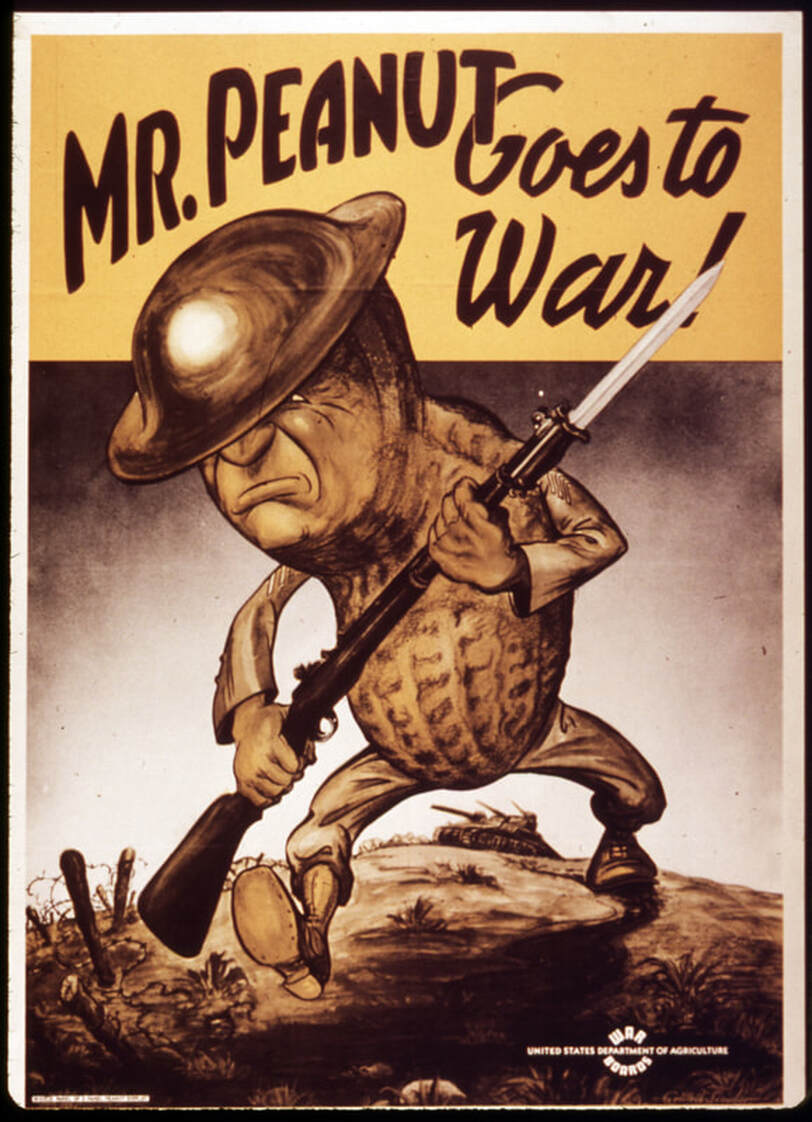

When you think of rationing in World War II, you may not think of peanuts, but they played an outsized role in acting as a substitute for a lot of otherwise tough-to-find foodstuffs, mainly other vegetable fats. When the United States entered the war in December, 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the dynamic of trade in the Pacific changed dramatically. The United States had come to rely on cocoanut oil from the then-American colonial territory of the Philippines and palm oil from Southeast Asia for everything from cooking and the production of foods like margarine to the manufacture of nitroglycerine and soap. Vegetable oils like coconut, palm, and cottonseed were considered cleaner and more sanitary than animal fats, which had previously been the primary ingredient in soap, shortening, and margarine. But when the Pacific Ocean became a theater of war, all but domestic vegetable oils were cut off. Cottonseed was still viable, but it was considered a byproduct of the cotton industry, not an product in and of itself, and therefore difficult to expand production. Soy was growing in importance, but in 1941 production was low. That left a distinctly American legume - the peanut. Peanuts are neither a pea nor a nut, although like peas they are a legume. Unlike peas, the seed pods grow underground, in tough papery shells. Native to the eastern Andes Mountains of South America, they were likely introduced to Europe by the Spanish. European colonizers then also introduced them to Africa and Southeast Asia. In West Africa, peanuts largely replaced a native groundnut in local diets. They were likely imported to North America by enslaved people from West Africa (where peanut production may have prolonged the slave trade). Peanuts became a staple crop in the American South largely as a foodstuff for enslaved people and livestock, but the privations of White middle and upper classes during the American Civil War expanded the consumption of peanuts to all levels of society. Union soldiers encountered peanuts during the war and liked the taste. The association of hot roasted peanuts with traveling circuses in the latter half of the 19th century and their use in candies like peanut brittle also helped improve their reputation. Peanuts are high in protein and fats, and were often used as a meat substitute by vegetarians in the late 19th century. Peanut loaf, peanut soup, and peanut breads were common suggestions, although grains and other legumes still held ultimate sway. George Washington Carver helped popularize peanuts as a crop in the early 20th century. Peanuts are legumes and thus fix nitrogen to the soil. With the cultivation of sweet potatoes, Carver saw peanuts as a way to restore soil depleted by decades of cotton farming, giving Black farmers a way to restore the health of their land while also providing nutritious food for their families and a viable cash crop. During the First World War, peanut production expanded as peanut oil was used to make munitions and peanuts were a recommended ration-friendly food. But it was consumer's love of the flavor and crunch of roasted peanuts that really drove post-war production. By the 1930s, the sale of peanuts had skyrocketed. No longer the niche boiled snack food of Southerners or ground into meal for livestock, peanuts were everywhere. Peanut butter and jelly (and peanut butter and mayonnaise) became popular sandwich fillings during the Great Depression. Roasted peanuts gave popcorn a run for its money at baseball games and other sporting events. Peanut-based candy bars like Baby Ruth and Snickers were skyrocketing in sales. And roasted, salted, shelled peanuts were replacing the more expensive salted almonds at dinner parties and weddings. Peanuts were even included as a "basic crop" in attempts by the federal government to address agricultural price control. They were included in the 1929 Agricultural Marketing Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, and an April, 1941 amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. Peanuts were included in farm loan support and programs to ensure farmers got a share of defense contracts. By the U.S. entry into World War II, most peanuts were being used in the production of peanut butter. And while Americans enjoyed them as a treat, their savory applications were ultimately less popular as an everyday food. But their use as source of high-quality oil was their main selling point during the Second World War. Peanut oil was the primary fuel in Rudolf Diesel's first engine, which debuted in 1900 at the Paris World's Fair. Its very high smoke point has made it a favorite of cooks around the world. During the Second World War peanut oil was used to produce margarine, used in salad dressings and as a butter and lard substitute in cooking and frying. But like other fats, its most important role was in the production of glycerin and nitroglycerine - a primary component in explosives. Which brings us to our imagery in the above propaganda poster. "Mr. Peanut Goes to War!" the poster cries. Produced by the United States Department of Agriculture, it features an anthropomorphized peanut in helmet and fatigues, carrying a rifle, bayonet fixed, marching determinedly across a battlefield, with a tank in the background. Likely aimed at farmers instead of ordinary households, Mr. Peanut of the USDA was nothing like the monocled, top-hatted suave character Planter's introduced in 1916. This Mr. Peanut was tough, determined to do his part, and aid in the war effort. The USDA expected farmers (including African American farmers) to do the same. Further Reading: Note: Amazon purchases from these links help support The Food Historian.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

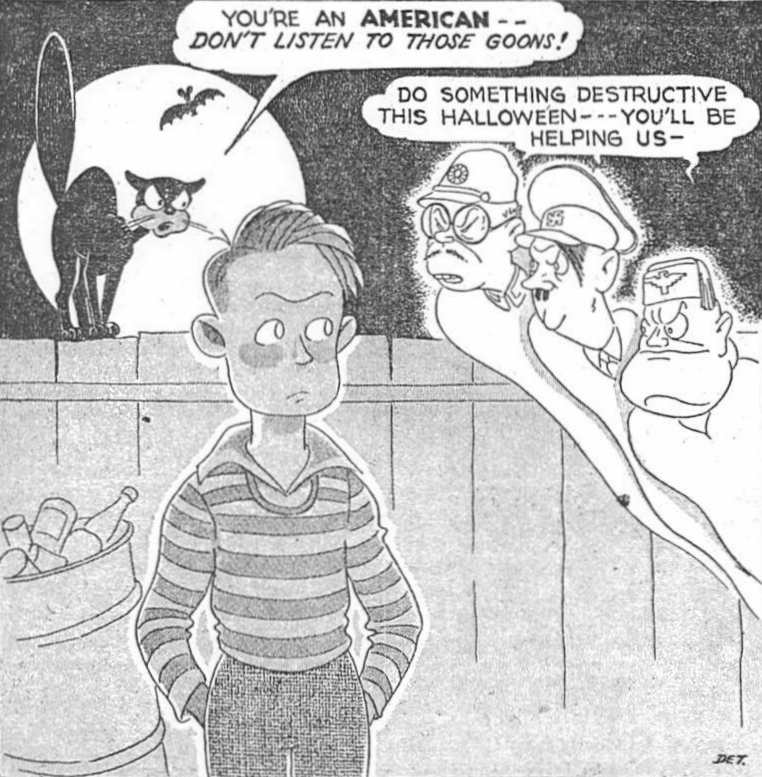

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month!  Cartoon published in the "San Diego Union," October 25, 1942. Ghosts of Emperor Hirohito of Japan, Adolph Hitler of Germany, and Benito Mussolini say in unison, "Do something destructive this Halloween - you'll be helping us -" to a teenaged boy in an alley. A black cat on the fence behind him says, "You're an AMERICAN - don't listen to those goons!" Trick or treating today is usually about young children, costumes, and lots of candy. In many communities, it's over by 8 or 9 pm. But historically, trick or treating was more about the tricks than the treats. Going door to door threatening tricks if treats were not offered instead is very old, but has deeper roots in association with Christmas than with Halloween. Despite the tradition's age, going door to door for treats on Halloween was not widely practiced in the United States until the 20th century. The pranks, however, were popular among teenaged boys. From the relatively harmless pranks like soaping car windows and placing furniture on porch roofs to the destructive ones like slashing tires, breaking windows, egging houses, and starting fires in the streets, pranks were common in communities across the country. The war changed all that. Halloween, 1942 was the first since the United States entered the war in December, 1941. Across the nation, newspapers published warnings to would-be prankers that destructive acts of the past would no longer be tolerated. This one, published on October 30, 1942 in The Corning Daily Observer in Corning, California, was typical of other messages other newspapers: "Hallowe'en Pranks Are Out For the Duration" "The destructive Hallowe'en pranks of breaking fences, stealing gates, deflating auto tires, ringing door bells to disturb sleepers, soaping windows, and all other forms of the removal or destruction of buildings or property are definitely out and forbidden on Hallowe'en night, according to word from Corning city officials. "Supplies are needed for national defense and are too scarce to permit misuse. "Word comes from Washington that individuals committing such offense shall be prosecuted as saboteurs and be treated accordingly. "Corning officials state that there will be no fooling about this matter this year and anyone contemplating 'having fun' will be treated with severely." The newspaper cartoon above, published in the San Francisco Union on October 25, 1942, illustrates just this sentiment. In it, the ghosts of Japanese Emperor Hirohito, German Chancellor Adolph Hitler, and Italian fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini egg on a young boy hanging out in a dark back alleyway. "Do something destructive this Halloween - - - You'll be helping us - " they tell him. On the high fence behind the boy stands a black cat, back arched in anger, silhouetted by a full moon. He says to the boy, "You're an American - - Don't listen to those goons!" Conflating Halloween pranks with sabotage and aiding the Axis powers was no joke. The November, 1942 newspapers feature stories of pranksters waking sleeping war workers, scaring their neighbors by setting off air raid bells, and causing car accidents by leaving debris in the roads. Several ended up in court, and some got buckshot wounds from angry homeowners for their efforts. Wartime propaganda like this was common - caricatures of the Axis leaders showed up frequently in newspapers, cartoons, and propaganda posters. For Halloween, they made convenient bogeymen. World War II was the beginning of the end of Halloween tricks. Although more innocuous pranks like egging houses and cars and toilet-papering trees and porches continued to be hallmarks of Halloween mischief, the days of fires in the streets, broken windows, and other real crimes were largely in the past. Communities that had previously celebrated Halloween with private parties at home, shifted to more public events like parades, community dances, and trick-or-treating geared toward small children getting treats rather than teenagers engaging in tricks. Further Reading If you'd like to learn more about Halloween during World War II, check out these additional resources:

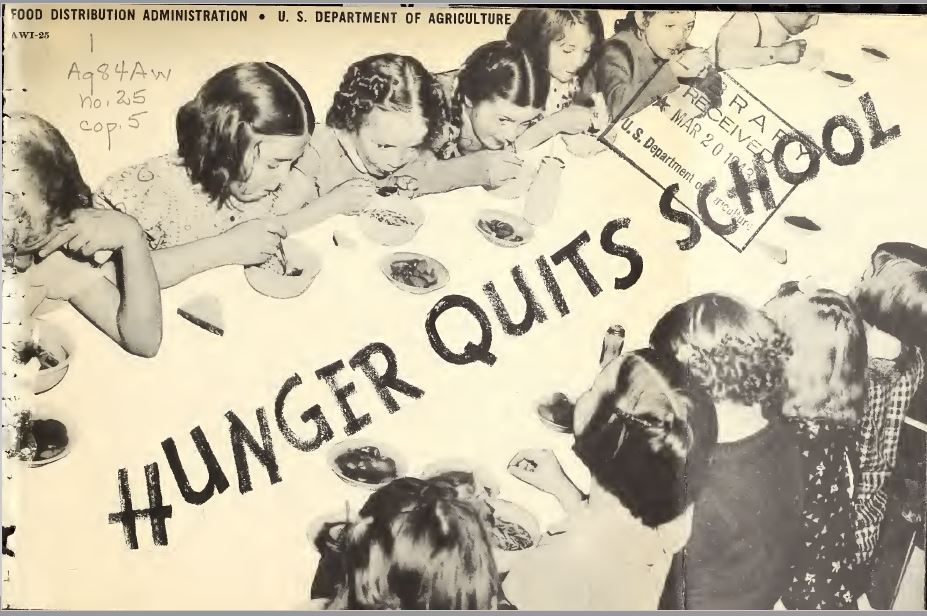

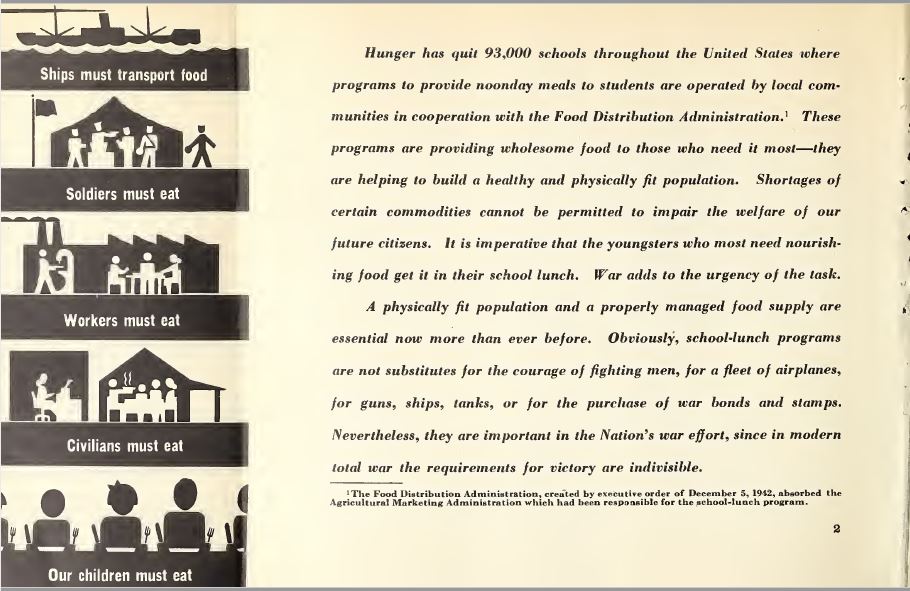

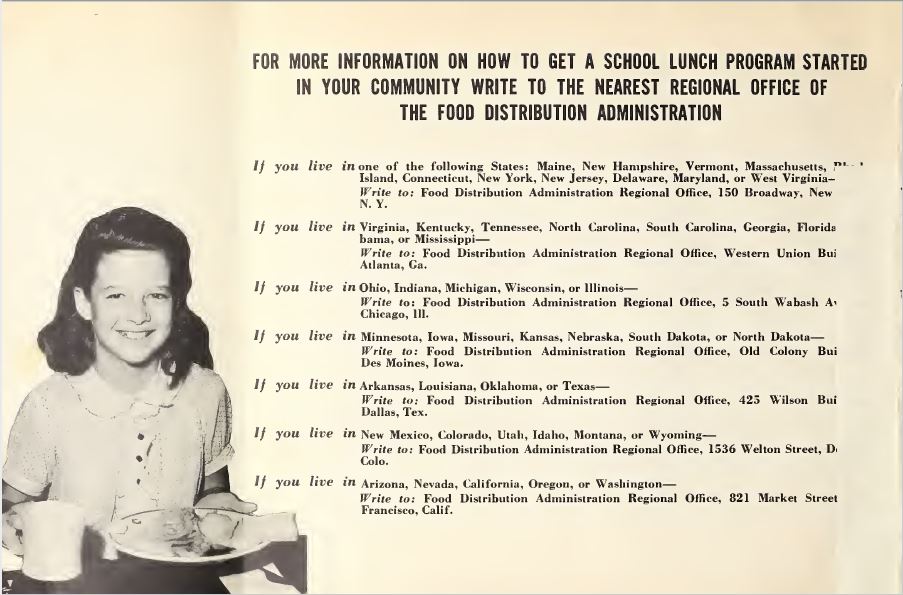

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! In 1943, the USDA published the informational booklet Hunger Quits School. On December 5, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the Food Distribution Administration, which oversaw, among other things, the school-lunch program. School lunch was influenced in part by the military draft. As many as a quarter of recruits were rejected for military service due to malnutrition. The panic around military readiness lead to many advancements in nutrition science and education of ordinary Americans about nutrition, including the development of the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations and yes, even school lunch. I've transcribed and shown the booklet in its entirety for your reading pleasure and edification. As you read you'll see how clearly school lunch programs were tied to military readiness even in the period, as well as how their execution differed in various communities. If you'd like to learn more about the history of school lunch, scroll to the bottom for reading recommendations. "Hunger has quit 93,000 schools throughout the United States where programs to provide noonday meals to students are operated by local communities in cooperation with the Food Distribution Administration. These programs are providing wholesome food to those who need it most - they are helping to build a healthy and physically fit population. Shortages of certain commodities cannot be permitted to impair the welfare of our future citizens. It is imperative that the youngsters who most need nourishing food get it in their school lunch. War adds to the urgency of the task. "A physically fit population and properly managed food supply are essential now more than ever before. Obviously, school-lunch programs are not substitutes for the courage of fighting men, for a fleet of airplanes, for guns, ships, tanks, or for the purchase of war bonds and stamps. Nevertheless, they are important in the Nation's War effort, since in modern total war the requirements for victory are indivisible." Images to left of text: Stylized black and white warship "Ships must transport food," stylized soldiers in a mess tent "Soldiers must eat," stylized workers in a factory with lunch room "Workers must eat," stylized woman typing and separate building with family in kitchen "Civilians must eat," stylized children sitting at table with knives and forks "Our children must eat." "WHY COMMUNITY SCHOOL-LUNCH PROGRAMS? "From the standpoint of the local community the reasons for operating lunch programs in the schools are immediate and easy to understand. Mothers and fathers, teachers and school administrators, doctors and health officers, and others in the community know the importance of having children eat properly. Since most children are away at school during lunch time for most of the year, the school lunch is an important part of the total diet of the individual. "Because parents, teachers, and others know the importance of proper food, that doesn't necessarily mean that all school children get the right kind of lunch or any lunch at all for that matter. In many cases, parents don't have enough money to put the right kinds of food in their children's lunch pails. In some cases - and this is increasingly true as more women go into war work - parents just don't have the time to put up the right kind of lunch for their children. In other cases, parents aren't well enough informed about nutrition to prepare an adequate lunch for their children. "All these and other factors have prompted local people to establish school-lunch programs as community enterprises. Programs are currently in operation to provide noonday meals to children in schools in every State and the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Thousands of persons - parents, teachers, volunteer workers, and well as paid workers - are giving their time and effort to carry on these projects, and millions of children are benefiting. "Although the Food Distribution Administration of the United States Department of Agriculture cooperated in school lunch programs in 93,000 schools during the 1941-42 school year by furnishing various foods without charge, the major responsibility for initiation of each program and for its successful operation is a community responsibility." Images to the right of text: Above, photo of young white boy outside a school eating a sandwich "The Cold Sandwich is no substitute." Below, photo of white children eating soup at a long table, caption continues ". . . For a Well-Balanced Hot Lunch." "METHODS OF ORGANIZATION DIFFER Just as there are tremendous variations in the types of communities, so are there considerable differences in the types of school-lunch programs. The complex organization of city life may find a parallel in the organization of the school lunch program in a large metropolitan area. In one large city, food for the lunch program is prepared in a big central kitchen. Hundreds of workers are engaged in such jobs as meal planning, food preparation, and dishwashing. From this central kitchen the food is delivered in heat-retaining containers by truck to the individual schools, where it is served to the children in lunchrooms. The children who can afford to pay for their meals do so with coupons which they buy at the school; those who cannot afford to pay are given coupons without charge. "The less complex pattern of life in rural areas may likewise be reflected in the organization of the school-lunch program. In one rural one-room school - and there are many of them in the United States - the children of the school bring various foods, such as potatoes and other vegetables, and seasonings from home. The teacher, with the assistance of the older students, prepares a single hot dish, usually a soup, a stew, or a boiled dinner. This hot dish is supplemented with foods which lend balance to the meal and can be eaten without cooking, such as citrus fruits or apples. The children set the tables and wash the dishes when the meal is finished. "These are but two of the many ways in which school-lunch programs are carried on. In operation they look easy. The routine is like clockwork. Each participant knows his job and does it. But even the most simple school-lunch project requires careful planning and hard work. Its successful operation depends on the continuing active interest of the local community." Images to left of text: Top, black and white photo of white adult women helping white students at lunch table, "The teacher, with the assistance of volunteers in the community, prepares the lunch." Bottom, black and white photo of open kitchen with white women cafeteria workers and line of white children, "Full-time workers prepare the food in a central kitchen from which it is delivered to the individual schools." "HOW TO GET STARTED IN YOUR COMMUNITY "Suppose the school in your community does not have a lunch program and you would like to see one in operation. How do you go about getting it started? "The first thing to keep in mind is that this is a job for your local people - yourself and your neighbors. Various agencies of the Government may lend you technical assistance, but the primary responsibility is yours. "If you have the interest and the willingness and the perseverance to follow through on a community lunch program, the thing to do is to get together with your neighbors, the parents of other school children, and see how much interest you can arouse and how much support you can get for the proposal. You will need much support if your plan is to be a success. "What you do next depends on what kind of community you live in. The procedure in a city of 100,000 population is different from that in a rural area. The steps to take are different in a city of 20,000 from those in a village of 2,000. But the procedure that has been followed in these different types of communities will give you an idea of what lies ahead in your effort to get started. "In one city of more than 100,000 population a group of mothers presented their proposal for a school-lunch program to the teachers and the principal of their neighborhood school. They were given a sympathetic hearing and arrangements were made to present the plan to the city superintendent of schools and the board of education. The meetings resulted in a survey to ascertain what facilities were available in the various schools for the operation of a lunch program on a city-wide basis, what additional facilities would have to be provided, and what would be needed in the way of financing. "The survey completed, plans were laid to put the school-lunch program into operation. Some of the needed facilities were provided from public funds, and" [. . . continued on next page] Image to right of text: Black and white photo of seated white adults as at a public meeting, "This is a job for local people . . . yourself and your neighbors." [continued from previous page] "the remainder was purchased by a number of civic and fraternal organizations which took an interest in the project. A permanent staff of paid workers was hired, and their work was supplemented by the work of volunteers. Much of the food was purchased locally, but some was provided without cost by the Food Distribution Administration. Those children who could pay a nominal sum for their lunch did so, and those who could not afford to pay were fed without charge. "Teachers took the initiative in serving lunches at school in one village of 2,000. They had seen some children sitting out in the cold eating sandwiches and others having nothing at all to eat. Investigating the possibilities of doing something about it, they learned that a school-lunch project was in operation in a nearby community. At the next meeting of the parent-teacher association they brought up the idea of a school-lunch program. The result was the appointment of a committee to visit the neighboring village and see how the program operated there. The committee made an enthusiastic report at the next meeting, and it was decided to present the whole matter to the local school board. "After a number of conferences with representatives of the State welfare department, the FDA, and other interested groups, the school board agreed to formally sponsor the lunch program. A lunchroom was set up in part of the school basement which was not in use. The county home demonstration agent provided technical assistance in meal planning. Two full-time paid workers were hired, and the rest of the labor forced was made up of volunteers. "The entire community, in one rural area, pooled its efforts to get a lunch program going in its one-room school. It was a real job, as the school lacked" [. . . continued on next page]. Images to left of text: Top photo, white adults gather around a table looking at papers "Parents and school authorities discuss a proposed school-lunch program." Bottom photo, white adults sit in auditorium, "Civic and fraternal organizations play an important part in the success of many school-lunch programs." [continued from previous page] "everything in the way of facilities and had no available space for cooking or serving. The men of the community solved the problem by getting together enough salvaged lumber and building a lean-to addition to the school, also tables and benches. The women of the community meanwhile organized a shower to collect the necessary pots, pans, and other cooking utensils. A merchant in the nearby town donated a second-hand stove. Each child brought his dishes and "silver" from home. Each family provided foods, and the mothers took turns going to the school to do the cooking. The school board, of course, approved the undertaking and formally sponsored the program to make it eligible for FDA assistance. "Should you contact anyone else for help in getting a school-lunch program going in your community? There is no one answer. In many counties there are home-demonstration agents, home-economics teachers, and home supervisors of the Farm Security Administration who can supply technical advice and assistance. Parent-teacher organizations, civic organizations, chambers of commerce, veterans' organizations and auxiliaries, State and local education departments, State and local health organizations, State and local welfare agencies, and the WPA are among the groups which have helped in other communities. In many cities there are representatives of the Food Distribution Administration who can supply information and advice regarding procedure for obtaining reimbursement from the FDA for the purchase of specified foods. "Your first objective in getting a school lunch program started is, of course, better meals for the children in school. This, too, was the main objective in the thousands of communities which are now operating the programs. These communities have found that many benefits to the children in school have stemmed from better nutrition." Images to right of text: top photo, white women stand next to table of plates of food, actively plating, "Teachers took the initiative in serving school lunches in a small community. Bottom photo, two white women stand in kitchen cooking, "Lunches like this mean more adequate diets for millions of children every day." "BETTER NUTRITION NOT THE ONLY BENEFIT "Records kept in many schools show that attendance is better after a school-lunch program is put in operation than it was before. One school reports 11 percent fewer absent than before the lunch program was started, another 8 percent; and still another 15 percent. Investigation shows that in many cases the better attendance is the result of less illness. Proper food does much to prevent illness, especially in growing children. "Thousands of doctors and dentists have gone into the armed forces. War needs have taxed our health facilities all along the line. It is more important than ever that as much illness as possible be prevented. To the extent that school lunches keep children healthy they are making a direct contribution to the welfare of the Nation at war. "There are many striking reports of children who have been built up physically as a result of eating school lunches. In one midwestern community an undernourished boy gained 25 pounds during a single school year. Many examples like this could be cited. Not only such run-down children, but in many cases the entire class of a school reports better physical fitness as a result of school lunches. "Many prominent health authorities have pointed out that it is a waste of the taxpayers' money to try properly to educate children who are malnourished. They simply cannot do good work when they are hungry. Such records as have been kept show that in almost every school where adequate lunches are provided the students are making better progress in their studies than formerly. "Teachers report that students are better behaved when they are properly nourished. Eating together in groups improves the table manners and the per-" [. . . continued on next page] Images to left of text: Top photo of white men administering vaccinations to other white men, "Thousands of doctors and dentists have gone into the armed forces." Bottom, young white children play on equipment outside, "Keeping children healthy is a direct contribution to the welfare of the Nation at war." [continued from previous page] "[per]sonal habits of many youngsters. Through the example of watching their schoolmates eat certain foods, children come to like foods previously unfamiliar. They eat what is put on the table. "In many communities the benefits of the lunch program are carried into the home. Children have reported back to their mothers the things that they learn about diet and better nutrition, with the result that the meals of whole families frequently have improved. "It is apparent that these benefits to children are all good reasons for parents, teachers, and local communities to be interested in school-lunch programs. How about the Federal Government and the Food Distribution Administration? "FDA'S PART IN SCHOOL-LUNCH PROGRAMS "One of the important jobs of the FDA is to assist in the management of the Nation's wartime food supply through the stimulation of increased production, the maintenance of machinery for orderly marketing, and the prevention of waste. School lunches, in addition to feeding those who most need proper nourishment, are one of the devices used in helping to do these jobs. "In recent months the war effort has made it necessary not only to maintain existing levels of food production but to increase these levels greatly. Although there has been a tremendous expansion in food production during the past year, some production goals have been revised upward. Under these conditions, when concerted efforts are being made to increase food production, it is important that farmers be able to market all they grow. Market stability is thus an important factor in stimulating increased production. "Not only is market stability important as an incentive to ever increasing output, but it is important in guarding against waste of food already produced." Images to right of text: top, a white farmer stands in the furrows of a field with sacks of potatoes, "It is important that good use be made of all that farmers produce." Bottom, two white men shake hands outdoors, "Sponsors buy from local producers and are reimbursed by the Food Distribution Administration." "In the past unstable markets sometimes made it impossible for farmers to harvest their entire crop and sell it at a price that would cover their costs. The result, when such conditions prevailed, was that part of the crop was not harvested but was left in the fields or in the orchards to rot. Such conditions might arise again for some commodities, even though supplies of certain other foods may be short, and if they do the school-lunch programs are a mechanism to prevent possible waste. "Sometimes food purchased originally for shipment abroad under the lend-lease program could not be used for this purpose because of changed requirements of our allies, lack of shipping space, or other uncontrollable factors. In such cases the school-lunch program provided a desirable outlet for the commodities. "In the past, the FDA's job in connection with school-lunch programs was to buy up foods and to channel them to schools for use by the youngsters who needed them most. Purchases were sent in carlots to the welfare departments of the various States. The State welfare department distributed foods to county warehouses which in turn distributed part of the supply for use in lunch programs in eligible schools. "Shortages born of the war - transportation, equipment, manpower - necessitated a revision of this distribution plan. In some large communities, commodities are still distributed to schools from warehouses operated by State welfare departments, but in most communities the program is now carried on under a local purchase plan. "Under this new local purchase plan, the FDA reimburses the sponsors for the purchase price of specified commodities for the lunches. The commodities eligible for purchase under the plan are given in a School Lunch Foods List which is issued from time to time. Products in regional abundance and those high in nutritional value have first consideration in compiling the lists. Sponsors buy from producers or associations of producers, or from wholesalers or retailers. They are reimbursed for the cost of the commodities up to a specified amount" [. . . continued on next page]. Images to left of text: top, two men load stack barrels, "A few foods are still available from the FDA for delivery to schools in some areas." Bottom, box trucks lined up outside a building as a man loads a box, "Sponsors arrange for the delivery of foods to the schools where they are used." [continued from previous page . . .] "which is based on the number of children participating, the type of lunch served, the financial resources of the sponsor, and the cost of food in the locality. "In addition to those foods for which the FDA provides reimbursement of the purchase price, local sponsors buy with their own funds such additional commodities as are needed to round out the meals. What better use can be made of some of our food supplies than to make them available to growing children who otherwise may not get enough to eat? "WHAT SCHOOLS ARE ELIGIBLE? "Schools eligible to participate in the program must be of a nonprofit-making character and must serve lunches to children who need them. Schools receiving FDA assistance must permit no discrimination between children who pay for their lunches and those unable to pay. A formal sponsor, representing the school, must enter into an agreement with the FDA that the conditions governing the program will be complied with. Nonprofit-making nursery schools and child-care centers are eligible for participation in the program. "From the standpoint of our national welfare it is important that all school children be properly nourished, and that all food produced be properly utilized. This explains the interest of the Federal Government in the community school-lunch program, since the Government represents all the people acting in concert. "Although the school-lunch programs alone have not succeeded in reaching all children who need more adequate nourishment, they have been instrumental in bringing food to a substantial number of them. During the peak month of March 1942 the lunch programs in which the FDA was cooperating fed 6,000,000 children. Nor have the lunch programs alone succeeded in making possible the most effective utilization of all foods produced. But they have been one means of working toward these two objectives. "The lunch programs have been a means of forcing hunger out of a great many schools in the United States." Images to right of text: Top: young white girls at play on a see-saw. Middle: a school building. Bottom: a white nun gives a sandwich and bottle of milk to a young white boy. "FOR MORE INFORMATION ON HOW TO GET A SCHOOL LUNCH PROGRAM STARTED IN YOUR COMMUNITY WRITE TO THE NEAREST REGIONAL OFFICE OF THE FOOD DISTRIBUTION ADMINISTRATION "If you live in one of the following States: Main, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, or West Virginia - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 150 Broadway, New York, N.Y. "If you live in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, or Mississippi - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, Western Union Building, Atlanta, Ga. "If you live in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, or Illinois - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 5 South Wabash Ave., Chicago, Ill. "If you live in Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, or North Dakota - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, Old Colony Building, Des Moines, Iowa. "If you live in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, or Texas - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 425 Wilson Building, Dallas, Tex. "If you live in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Montana, or Wyoming - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 1536 Welton Street, Denver, Colo. "If you live in Arizona, Nevada, California, Oregon, or Washington - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 821 Market Street, San Francisco, Calif." And that is the end of the transcription! What did you think? Were there any surprises in there for you? I had known for a long time that the school lunch program was a way to use up agricultural surpluses AFTER the war, but hadn't realized that using up wartime surpluses was a factor since the beginning. I also liked the emphasis on treating children who couldn't afford to pay no differently than those who could. FURTHER READING: If you'd like to learn more about the history of school lunch, check out these additional resources. (Purchases made from Amazon links help support The Food Historian):

Happy reading! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

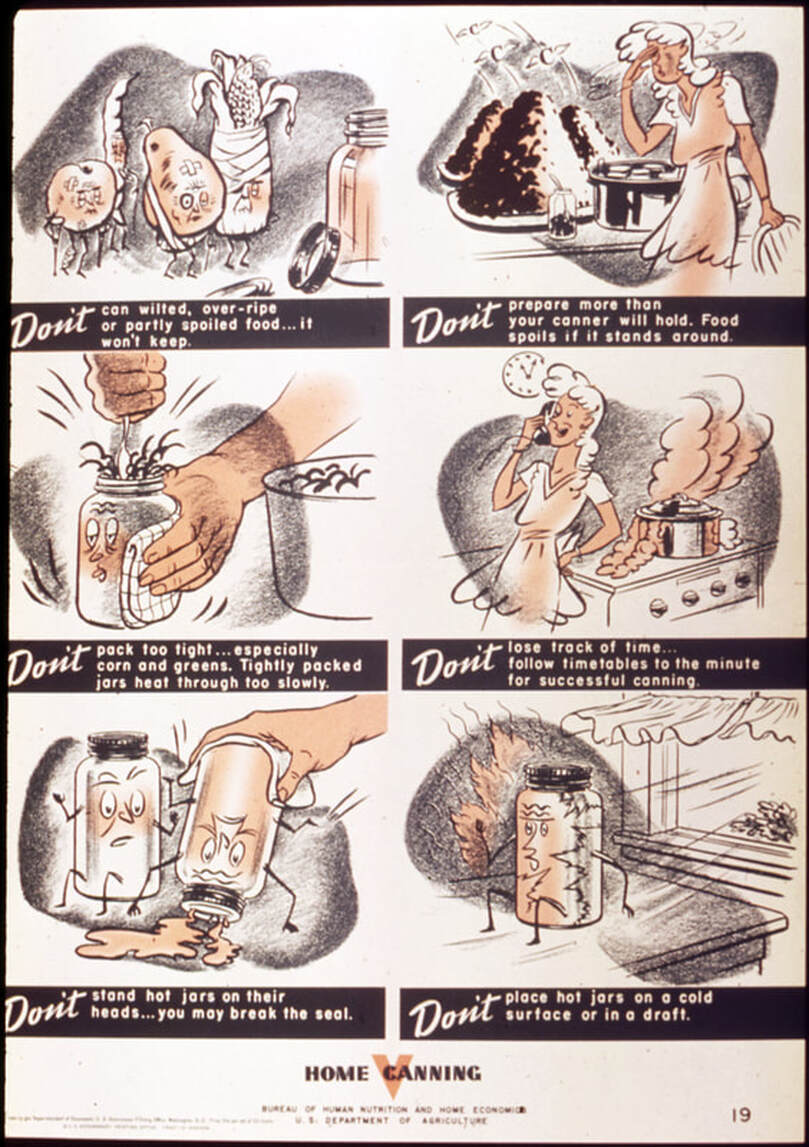

It's prime canning season! If you're facing a glut of tomatoes or more than ready for apple picking so you can make your own sauce, this post is for you. During both World Wars, home food preservation was vital to freeing up supplies of commercially canned goods for feeding soldiers and the Allies. But not everyone was used to canning at home, and even those who were experienced sometimes relied on unreliable or dangerous methods. For instance, my great-grandmother oven canned, which is no longer considered safe. And some folks still try to turn their jars upside down for a seal, which is not recommended. All canned foods work by creating a sterile vacuum seal. High-acid foods like fruit, tomatoes, and vinegar pickled foods can be canned in a water bath, where boiling water (212 F) kills bacteria and seals the jars. Low-acid foods like non-pickled vegetables and meats need to be pressure canned. The pressure canner increases the pressure inside the chamber, which allows water to boil at a much higher temperature. This kills all bacteria, including deadly botulism, and makes the low-acid foods safe to can. One of the ways home economists and the federal government tried to educate people about canning and food safety was through propaganda posters like this one. Here's the advice from the poster: "Don't can wilted, over-ripe or partly spoiled food... it won't keep." If you wouldn't eat it fresh, you shouldn't can it. Although lots of rhetoric during the war was about saving food and preventing waste, canning can only preserve, not restore the quality of food. Poor-quality ingredients makes for poor-quality canned goods, wasting time and effort. "Don't prepare more than your canner will hold. Food spoils if it stands around." Canning takes time, and leaving cut fruits or vegetables lying around waiting to be put into jars makes them more susceptible to collecting bacteria or spoiling. Canning depends on sterile jars and fresh ingredients. Although it can be tempting to work ahead, time your work carefully to avoid waiting. "Don't pack too tight... especially corn and greens. Tightly packed jars heat through too slowly." Canned goods need to be heated through entirely to create a proper vacuum seal and prevent the growth of bacteria. Especially for low-acid foods like corn and greens, proper heating is essential to successful canning. Tightly packed jars not only risked spoilage, they also wasted fuel as it would take them longer to heat through, if at all. "Don't lose track of time... follow timetables to the minute for successful canning." We've all been there. That's what kitchen timers are for. While over-cooking doesn't usually hurt, under-cooking can result in improper seals. Better to use the timer and be sure. Test kitchens and home economists and scientists developed the time tables to ensure a minimum amount of time in the boiling water bath or pressure cooker to ensure adequate seal and food safety. "Don't stand hot jars on their heads... you may break the seal." Although some people still do this to "ensure a good seal," a heat seal is not the same as a vacuum seal, and liquids touching the tops of the cans before they are fully cooled may break the seal and allow air and bacteria in, leading to spoilage. "Don't place hot jars on a cold surface or in a draft." They may break or explode. Seriously. This is also why canning jars need to be heated before filling - not only for sterilization, but also to prevent shock and cracks or breakage. Canning can be intimidating, and certainly time-consuming, but the push to get Americans to participate in home food preservation was a hard one. Although it can be difficult to balance the effort of canning with modern lives, the urgency of food preservation during World War II meant people carved out the time to make the effort. Do you can at home? I usually don't have the time, although nothing beats home canned applesauce (at least, my mom's style) and jam. A friend of mine keeps me supplied with amazing homemade jams. They're worth every penny. Especially since then I don't have to do the canning myself! Share your canning memories and stories (or horror stories) in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

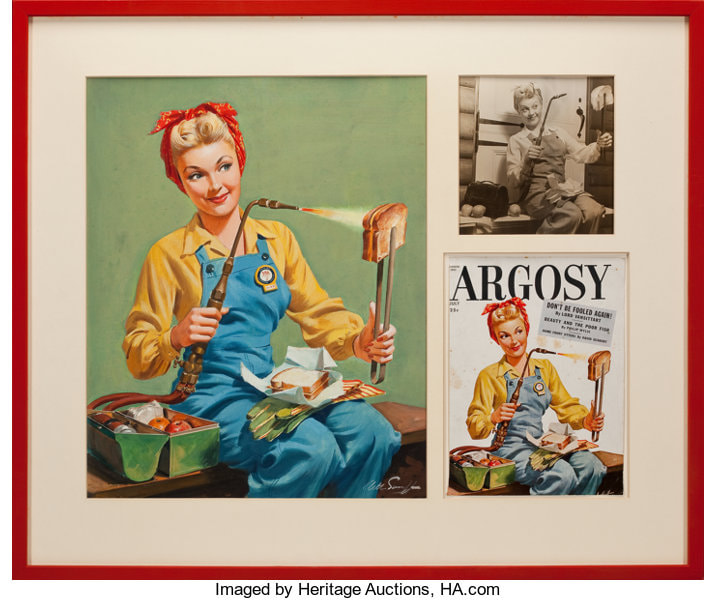

This image was making the rounds in some of my social media art groups, so I thought I would dig into the story behind it for World War Wednesday! Titled, "Lunch Break," and painted by commercial artist Arthur Sarnoff, the painting features a beautiful blonde woman in a red headscarf (a la Rosie the Riveter), a yellow blouse, and blue overalls using her welding torch and tongs to toast what appears to be a cheese sandwich. Another lays in her lap in a white paper wrapper, on top of her welding gloves. A green metal lunch box featuring a thermos, an apple, and orange, and another paper wrapped bundle of what appears to be more sandwiches sits on the bench before her. Although not quite done in pinup style, the painting is far more romanticized than, say, Norman Rockwell's "Rosie the Riveter," with her smudged face, dirty attire, and muscley arms. Sarnoff painted "Lunch Break" for Argosy magazine. Founded in the 1880s as a pulp short fiction magazine, by the Second World War it was shifting more towards a men's magazine, with some fiction interspersed with "true tales" of men doing heroic things. The style of art reflects that shift, with a pretty, dainty blonde using her blowtorch to make cheese sandwiches on her lunch break, rather than depicting her doing actual work. Her makeup, hair, and red-painted shaped fingernails are pristine, and the gloves in her lap look scarcely used, clean and with sharp creases still on the cuffs. I was not able to find a full-size image of the Argosy cover, so I don't know the date it was published. And while the badge on her overalls is large in the painting, the "words" are just gibberish brush strokes. I can only guess at its meaning. Although Rosie gets most of the attention, "Winnie the Welder" (sometimes also "Wendy the Welder") was in many ways more important than riveters. Women welders during the Second World War made up as much as 65% of welders in the country and were crucial to shipbuilding efforts for both warships and cargo and freight vessels. Women of all ages were thrown into welding with some cursory training, but for the most part their dedication and skill allowed them to adapt quickly to the new, often dangerous environment. As for the toasted cheese sandwich - although aged cheese like cheddar was officially rationed, cheese was often touted as a meat substitute during the Second World War. That bread doesn't precisely look like a whole wheat Victory loaf, though! And even holding it that far away, you'd have to be quick about toasting with an oxy-acetylene torch - they can get up to temperatures of 5,600 F. The fantasy depicted in "Lunch Break" is mostly just that - fantasy. But regardless of its historical accuracy, it's a striking image of concepts about women, work, and food during the Second World War. Further Reading:

To see some women at work (albeit in steal manufacturing, with just a glimpse of riveting and welding), you can watch the short documentary film below, "Women of Steel" (1943). The film is an odd mix of feminism and can-do attitude mixed with patriarchal ideas of what happens "when the boys come home." What a mixed message for women to be receiving during the war! Interestingly, however, it does depict the women using a factory's cafeteria, which was probably preferable to bringing your lunch from home. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! We've all had those days. Days where we forgot to bring lunch to work and can't get away to buy it, or when we bring a sad, cobbled-together lunch, or when we pick up fast food or something with empty calories. For many of us, a slow-moving afternoon or the distraction of a rumbling stomach isn't the end of the world. But during the Second World War, people didn't have the luxury of distraction of fatigue. This bold propaganda poster from c. 1943 features a yawning male worker leaning on the surface of what appears to be a stamping or hammering machine. He says, "Ho hum," feet crossed, leaning on his elbows, as a heavy block of metal descends toward his head. The poster reads, "Avoid fatigue! Eat a lunch that packs a punch!" During WWII, the United States engaged in total war. That meant that nearly every aspect of American society shifted toward the war effort. Nowhere was this more clear than in the everyday work of people in manufacturing. Men who weren't drafted for the war or working on farms often worked in factory settings. Factories that previously made machinery for consumer use - automobiles, refrigerators, washing machines, etc. - now found themselves manufacturing warplanes and Army jeeps and munitions. Factories worked on round-the-clock schedules, with three shifts a day. Some people worked much longer than 8 hours at a time. Although great strides had been made in ergonomics in factory work during the 1940s, the pressure of keeping up with military contracts and quotas was great. People often got too little sleep, and rationing made food supplies tight. During the war the U.S. federal government issued the Basic 7 - the first national nutrition guidelines ever issued. Based around the idea of balancing vitamin intake with protein, carbohydrates, and fats, the Basic 7 helped ordinary Americans better understand nutrition. Which is exactly what this poster is alluding to. "Eat a lunch that packs a punch" was a slogan also showed up in other posters, and alluded to calcium to keep bones strong, protein to build muscles, and Vitamin A to improve eyesight, among others. But this poster focuses on fatigue, which was a very real threat to the war machine. Tired workers made mistakes, hurt themselves, and could hurt or kill others. Operating flat out didn't leave room for mistakes, and a labor shortage thanks to the draft made skilled workers difficult to replace. Unbalanced meals, or not enough to eat, did not give war workers the energy they needed to perform at the highest levels at all times. The pressure of wartime work must have seemed unbearable at times. And with women increasingly joining the workforce and/or managing victory gardens and food preservation at home, not to mention coping with rationing, the idea of packing a large and nutritionally balanced lunch must have seemed like a lot of extra work for people. But while cafeterias were sometimes available, most people in factory work still packed their lunches. And while working at high speeds with dangerous equipment, it was worth it to make sure you weren't going to be too tired to do your job. There was no room for slacking off at work during the war, and getting proper nutrition to keep in peak physical health was so important the federal government spent a great deal of money advertising basic nutrition concepts (along with lots of posters about workplace safety) to ordinary Americans. Total war meant total commitment, total effort, and total focus. Staying healthy and well-fed was all part of total war. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

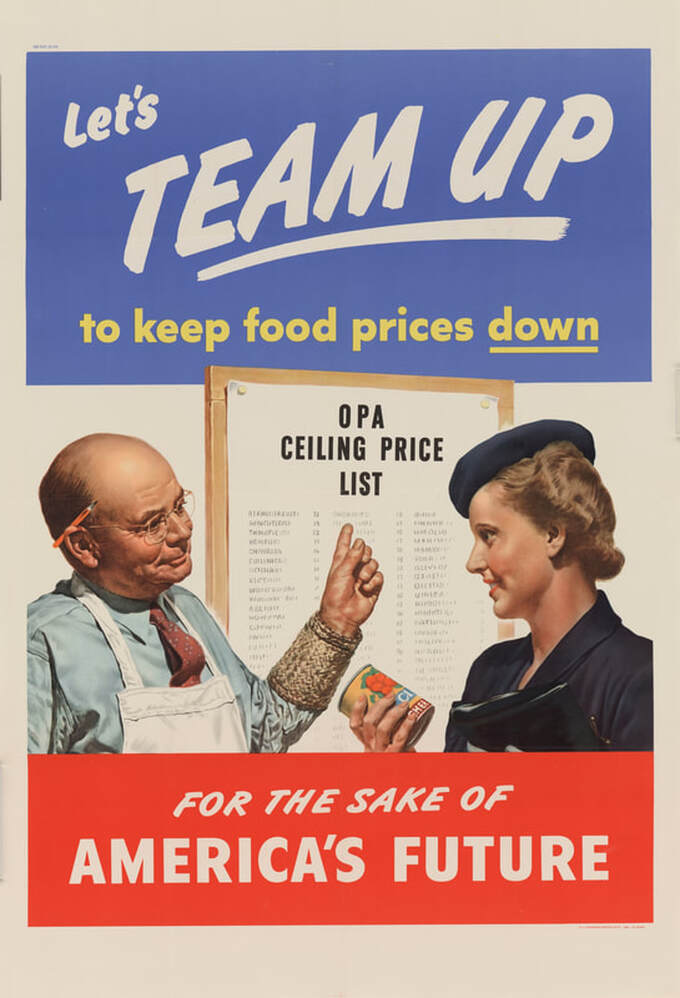

With all the talk of price increases and inflation these days, it's interesting to look to how these things were handled in the past. On a previous World War Wednesday, I talked about the differences between World War I and II and the "high cost of living," as it was called at the time. A big part of keeping prices affordable during the Second World War was not only mandatory rationing (it was voluntary in WWI), but also the Office of Price Administration (OPA) was able to freeze or set prices nationally for all consumer goods. Agricultural commodities were exempted from OPA control. Although the OPA was founded in 1941, it wasn't until 1943 that it settled on direct price control as the most effective means of regulation of consumer prices (The Oregon State Archives has a great overview of the OPA and price controls as part of an online exhibit on WWII). Although direct price control - "ceiling prices" they were called at the time - were extremely popular with the general public, retailers and especially manufacturers were constantly looking for ways around the regulations or to weaken them. The OPA used peer pressure and enlisted an army of housewives to report on those not adhering to regulations. This propaganda poster, one of many produced by the OPA, features a well-coiffed housewife holding a can of what appear to be tomatoes (or maybe cherries) smiling at a balding grocer, who in turn points rather wryly to a posted placard reading "OPA Price Ceiling List." The text of the poster read "Let's TEAM UP to keep food prices down for the sake of America's Future." Ceiling prices were published by the OPA and required to be posted in retail spaces, especially food, which was among the most price-controlled area of American life. Although small businesses could charge slightly higher prices than regional chains, the prices often differed by only a few cents, and were designed to help out the small businesses by giving them slightly higher profit margins. Much of the propaganda around price control and rationing both calls for cooperation between retailers and consumers, and this poster is no exception. Retailers were expected to follow regulations and consumers were expected to only patronize retailers who were following the rules. That didn't stop a huge black market from developing, especially around meat. Despite massive quantities of meat being used to feed the armed forces and sent overseas to support the Allies, ranchers and meatpackers were unhappy with price controls and in the aftermath of the war some actively withheld meat from the market in an effort to create false scarcity and anger voters, who would oppose the price controls. By the fall of 1946, meat production had fallen by 80%. Angry voters blamed the party in power - the Democrats - rather than the ranchers and packers who were colluding to manipulate the market, and delivered a Republican win in the election of 1946 - the first since 1930. The tension between food producers and food consumers has a long history. In the "free" market, farmers and ranchers are rewarded for low yields and production because prices go up. Getting producers to produce enough to feed people affordably while still ensuring they make a fair profit is a dilemma that plagued the early 20th century. Finally, during FDR's New Deal, government funds were used to subsidize farmers through low-interest farm loans and also direct payments to steady the supply on the market and protect farmland from the Dust Bowl. These were revoked in the 1970s under Nixon's Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz of "get big or get out" fame. Instead, the government maintained an agricultural price floor - if the market price fell below the floor, the government would make up the difference to the farmer. So what happened? Of course prices instantly fell below the floor - because they could. Food manufacturers benefitted from purchasing commodity crops for less than they cost to produce, our modern processed food production flourished (to the detriment of our health), and taxpayers footed the bill. In the modern era, many economists (including at NPR) have used the jump in post-war inflation as the OPA was dissolved wholesale (instead of gradually increasing prices as economists of the period recommended) as proof that the OPA was always a bad idea, doomed to failure. But the people who hated the OPA the most seemed to be the people who stood to profit the most from inflation - the manufacturers, packers, and retailers who could pad their bottom lines with price increases in the name of "scarcity." Sound familiar? It seems to me as though the OPA, behemoth bureaucracy though it was, was more the victim of those determined to see if fail, at all costs, than a violation of the "natural order." Because although economists like to talk about scarcity driving up prices, they have very little to say about price increases that are not caused by scarcity, and even less to say about price increases on goods that people cannot afford to do without - like food and housing and healthcare. The tension between pro-business forces who oppose regulation and pro-consumer forces who support regulation date back to the 19th century in the United States. The conflict was present in the fallout from the Panic (and subsequent 7 year Depression) of 1893, in the industrial recessions of the early 20th century, and especially in the handling of the Crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression. FDR's New Deal and a dramatic increase in government regulation of business and the economy helped pull us out of the Depression (wartime defense spending didn't hurt either). But the OPA caused a strong negative reaction among the pro-business, anti-regulation groups that shifted politics back toward the myth of the "free" market. But while inflation did increase by as much as 20% after the OPA was dissolved, strong postwar wages helped mitigate the effects. Whereas wages in the modern era have largely stagnated for over a decade, especially for workers on the lower end of the economic spectrum. A few economists have discussed the morality of price gouging, but should we rely on the morals of businesses in a capitalist society? The tensions between pro- and anti-regulation forces are still at play in modern politics. After decades of deregulation, the Biden Administration has begun re-regulating or executing new orders on the environment, consumer protections, and immigration, but has yet to address the modern "high cost of living," although it is trying to reduce meat monopolies. But corporate consolidation has continued unchecked for decades, belying the "free market" and hurting consumers. It's a problem that won't be solved overnight. As prices for housing, food, healthcare, and other essential goods continue to rise, will we return to the lessons of the Office of Price Administration? That remains to be seen. I, for one, wouldn't mind a return to the "fair price" lists published in WWI. If politicians can't stomach a return to government regulations, maybe we can at least shame food corporations into sacrificing some of their record profits to ensure Americans have enough to eat. What do you think? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!  “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf, not the farmer of the United States who works and sacrifices to fill the holds of victory ships…,” says the narrator as an oversized silhouetted farmer pours grain into the hold of a ship. Still from the film "Food Will Win the War" (1942). Courtesy Cartoonresearch.com Previously, we met Jack Sprat and his wife in a fairytale cartoon propaganda poster. This week, we go all out total war with Walt Disney. Produced by Disney in 1942, "Food Will Win the War" was a propaganda film of the Agricultural Marketing Administration, under the auspices of the United States Department of Agriculture. Narrated like a newsreel, the cartoon illustrates the might of American agriculture, in brilliant technicolor. The cartoon illustrations of the overwhelming productivity of American agriculture compare mind-boggling production numbers to well-known landmarks and other Very Large Things. Flour to blizzards, bread to the Egyptian pyramids, tomatoes to the Rock of Gibraltar, cheese to the moon, etc. When getting to meat production, we get to see the Disney's Three Little Pigs, leading a parade of hundreds of hogs, playing "Who's Afraid of the Big, Bad Wolf?" on fife and drum. Periodically, we are reminded that the size of several of these items could crush Berlin, including a very plump blonde representing American fat and oil production. One scene compares American agriculture to a giant bowling ball, which is depicted rolling through Nazi headquarters (tattering the Nazi flag in the process), and bowling over pins caricaturing Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Emperor Hirohito. The film closes with a grim montage of the challenges faced by shipping and a call to the Four Freedoms outlined by FDR - Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. Like many propaganda films and newsreels from World War II, this one has plenty of bombast, with good and evil portrayed in stark black and white terms (even though the animation is in color). Released to American audiences on July 21, 1942, it had several goals. One was to buoy American confidence in food supplies. There were concerns that the U.S. was shipping too much produce overseas and that there would be shortages at home. These concerns were not unfounded, but wartime production increased enough that even though rationing eventually grew tight, everyone had enough to eat. Another was to impress upon foreign audiences that American production capacity was overwhelming and would strengthen the Allies, who had been at war for over two years already. In 1941, Disney was suffering major financial losses from Fantasia - it was a box office flop and made just a fraction of what it cost to produce. You can see the economy of animation in many of the scenes of this film - where largely still images move across the frame or zoom in or out - achieved by layering cells. But the success of Disney's animated films for the war effort helped keep the studio afloat during the war. They became well-known in particular for training films, as Disney animators were able to illustrate in fine detail mechanical operations and theoretical scenarios that would be difficult or impossible to film in real life. Some speculate that without World War II, Disney Studios might have gone under after only a few films. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

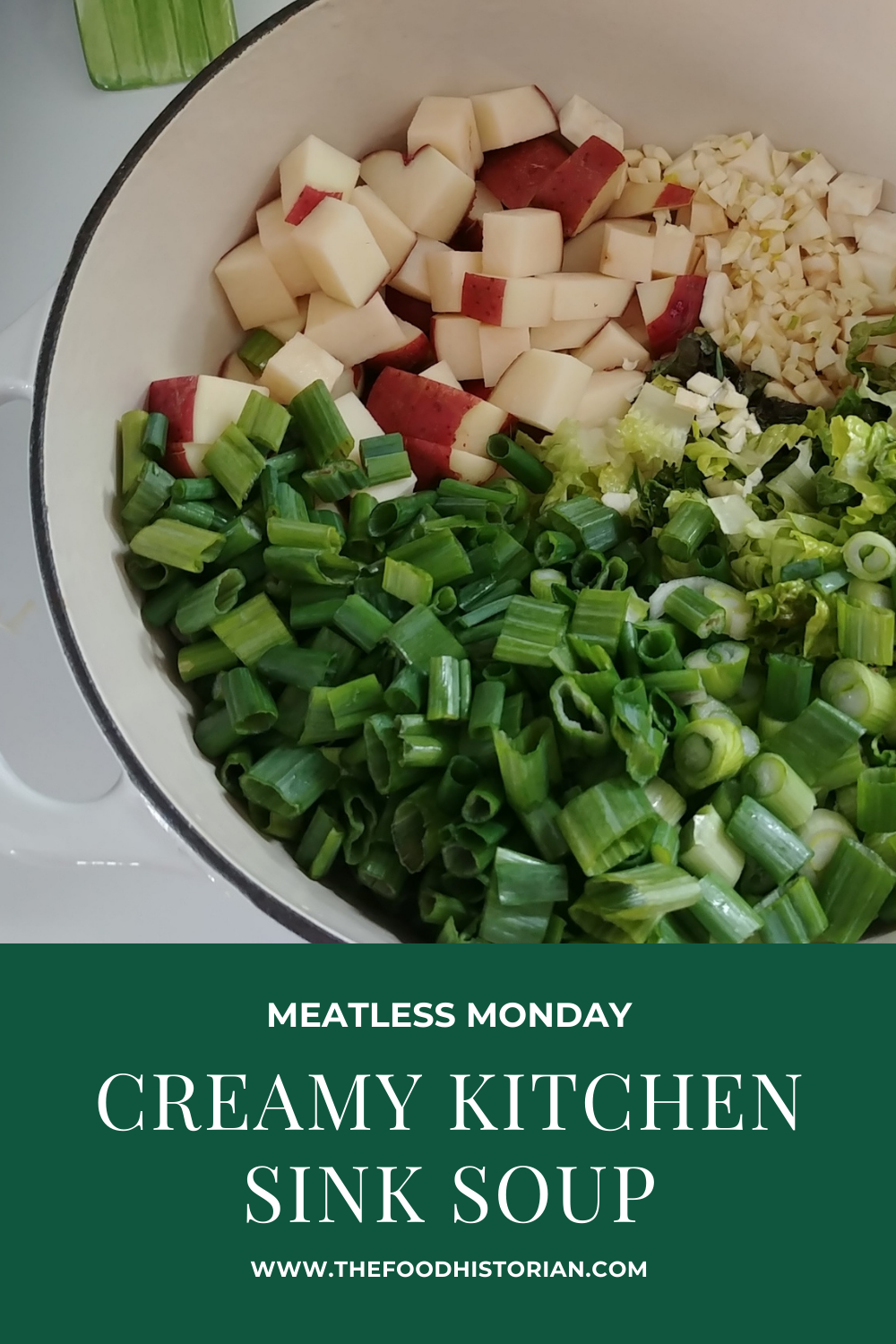

It's been cold and snowy lately here in the northeast, and sometimes you just have to have soup. But going to the grocery store in a snowstorm is ill-advised. This recipe lets you use up all kinds of bits and ends that might be languishing in your refrigerator.

This particular recipe is my own creation, based on what was in my kitchen, but is entirely inspired by history. Several parts of history, in fact. The first is reducing food waste. Historical peoples did not throw out potatoes just because they were starting to sprout, or lettuce because it was a bit wilted, and neither should you. Putting lettuce in soup is also extraordinarily historic, and a practice that should be revived. Another is that this recipe is based on one of my favorites, "Green Onion Soup," from Rae Katherine Eighmey's Hearts & Homes: How Creative Cooks Fed the Soul and Spirit of America's Heartland, 1895-1939 (2002). Eighmey read hundreds of agricultural magazines and gleaned recipes and wisdom from the farm home sections. Found in the December 26, 1924 issue of Wallace's Farmer, Green Onion Soup is a unique recipe. A combination of simply green onions and potatoes, the soup is cooked in a small amount of water, and then partially mashed right in the pot without draining. Cream and milk are added to thin the soup and add richness. The soup is comforting and nourishing and retains all of the vitamins and minerals that might otherwise be lost by draining away the cooking water. Which brings me to the final inspiration - vitamin retention in the style of recipes from World War II. By cooking the vegetables in the water that becomes the broth, you lose far fewer nutrients and flavor. Plus, other aspects of the soup are also quite appropriate to WWII - it's meatless, in line with rationing, and makes good use of milk, a favorite 1940s ingredient. Creamy Kitchen Sink Soup Recipe

I had a number of foods that needed using up that made their way into this soup: a few red potatoes, a head of wilted red lettuce, the fresh bits of baby spinach out of a box that was on the verge of getting slimy, a whole celery root starting to go a bit soft, some garlic starting to go green in the middle, and the tail end of a gallon of milk. The only fresh addition was two bunches of green onions. You could modify it pretty much however you want - any kind of greens, any kind of onion, any kind of root vegetable.

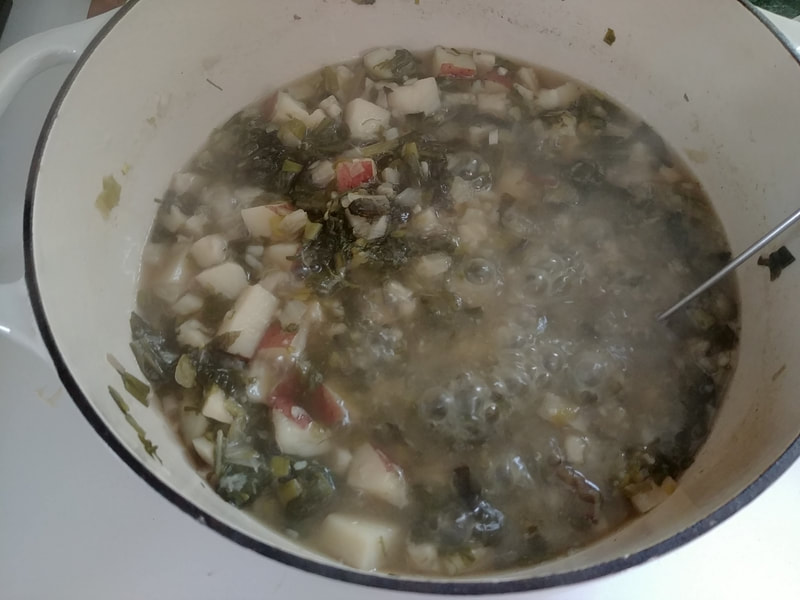

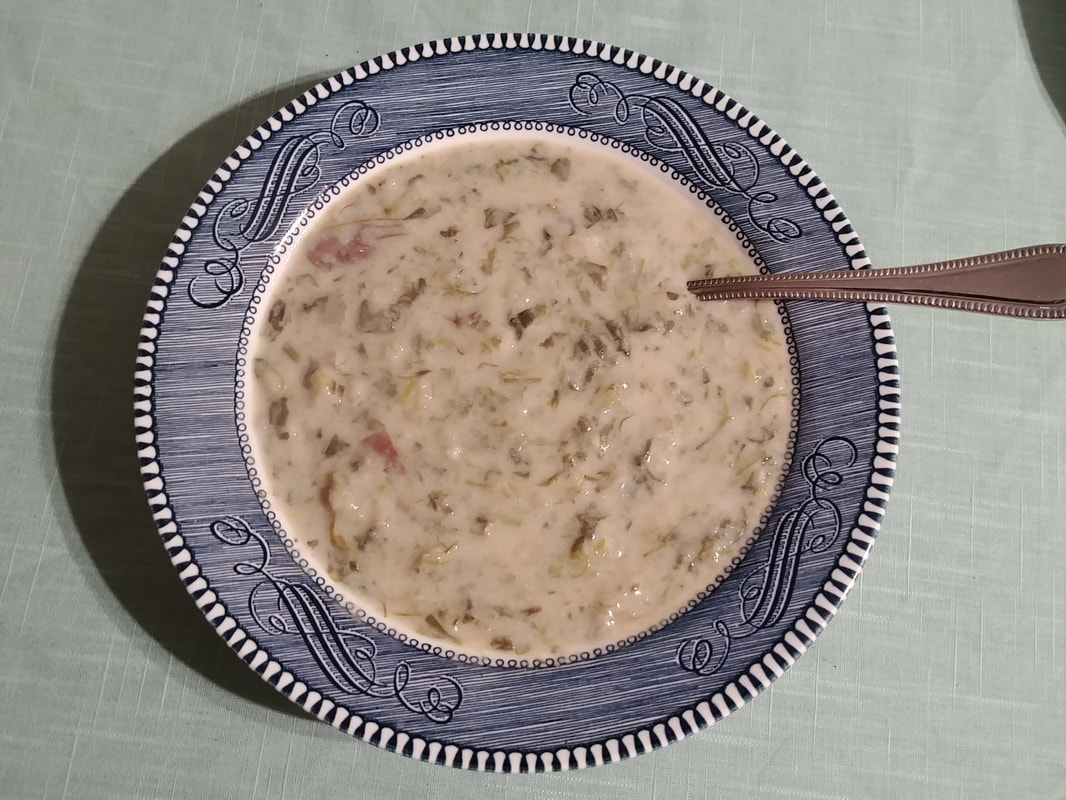

4 red potatoes 2 bunches green onions (scallions) 1 celery root 3 cloves garlic 1 head red lettuce 1-2 cups baby spinach water salt pepper 1/2 cup half and half 1 cup buttermilk whole milk Scrub and dice the potatoes, cutting away any eyes or bad parts, but leave the skin on. Slice the green onions, white and green parts. Cut away the knobbly skin from the celery root, then cut into small dice. Mince the garlic, wash and chop the whole head of lettuce. Add it all, with the spinach to a large stock pot and add water not quite to cover. Add at least 1 teaspoon salt (I used wild garlic flavored crystal salt languishing in a drawer) and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer hard until all vegetables are very tender and potatoes fall apart when pierced with a fork. Do not drain. Using a potato masher or sauce whisk, mash vegetables in the pot until blended with the water, leaving some chunks. Add a the half and half and buttermilk (or you could use part heavy cream, or leave out the buttermilk, or just use milk) then add milk to thin out the soup and to taste. Taste for salt and add more if necessary, along with pepper and whatever other herbs and spices you like. Serve nice and hot with buttered bread or toast. The buttermilk does add a nice, distinctive tang. If you don't have any, add a dollop of sour cream, or some plain yogurt, or a splash of lemon juice. You could make this vegan with plant-based milk and butter. For a different flavor, add whatever fresh herbs you have lying around - dill, parsley, basil, and cilantro would all be good here. Add vegetable broth and some lemon juice instead of milk for a bright, brothy soup instead of something creamy. Use sweet potatoes or squash and tomato broth with the greens. The possibilities are really endless.

If you'd like more interesting recipes, you can purchase Eighmey's book from Bookshop or Amazon - either way, if you do, your purchase will support The Food Historian!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

White Christmas (1954) is probably one of my favorite holiday films. I did not grow up watching it. In fact, my husband was the one who introduced me to it, but I fell in love. It's got everything - WWII, great relationships, music, dancing, everything wonderful and awful about putting on a show (former theater nerd, here), and of course, a heartwarming tale in a beautiful setting. Not to mention Bing Crosby's velvet voice. So when a friend, who had never seen White Christmas, suggested I make a dinner menu to go along with the film, I couldn't resist. She knew I'd done similar menus before (Star Wars and The Hobbit, respectively, both birthday parties I threw myself), but this one was fun because I could delve into all my vintage cookbooks for ideas. Now, there are a few foods mentioned or shown in the film. One of the first (and best) is the scene in the club car on the way to Vermont. Mentioned or shown foods include:

The other major scene is after hours, when sandwiches and buttermilk are the order of the day. Mentioned or pictured in this scene are:

Other foods shown include hotdogs by the fire and, of course, the General's enormous birthday cake. Clearly dinner is served in that scene, but it's difficult to see what. There was an added hiccup in all this menu planning - the friend in question is vegetarian. So guess what? A lot of that list is out the window! But I relish a good challenge, so I took to my cookbooks and got thinking. And here's what I came up with: I based my recipes largely on the foods of the late 1940s, focusing on New England recipes. Because although White Christmas was released in 1954, and clearly takes place in the 1950s, it was influenced by the earlier (and slightly more racist) Holiday Inn, which came out in 1942. In addition, the WWII connection between Bob and Phil (a.k.a. Wallace & Davis), made me think this menu needed a little bit of a 1940s flavor. Here's the menu:

No, those aren't typos - "lentilwurst" is what I call vegetarian liverwurst and while everything was good, that was the surprise hit of the night. I wish I had made a double batch because it was gone almost instantly. Maple Sirup (also not a typo - that's how they spelled it in the cookbook) Gingerbread was another delightful (if rather expensive) hit. Thankfully, we did not eat the whole cake in one sitting, although two days later we're down to the last piece. In an effort to spare you from the world's longest blog post, I'm going to be posting the recipes each day this week (probably more than one per day) as their own blog posts. Don't worry - I'll link them back here as they're posted so you can always find everything in one spot. You should get the whole menu before the weekend - just in time to plan a White Christmas Dinner and a Movie of your own! Happy eating! Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! As always, The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed