|

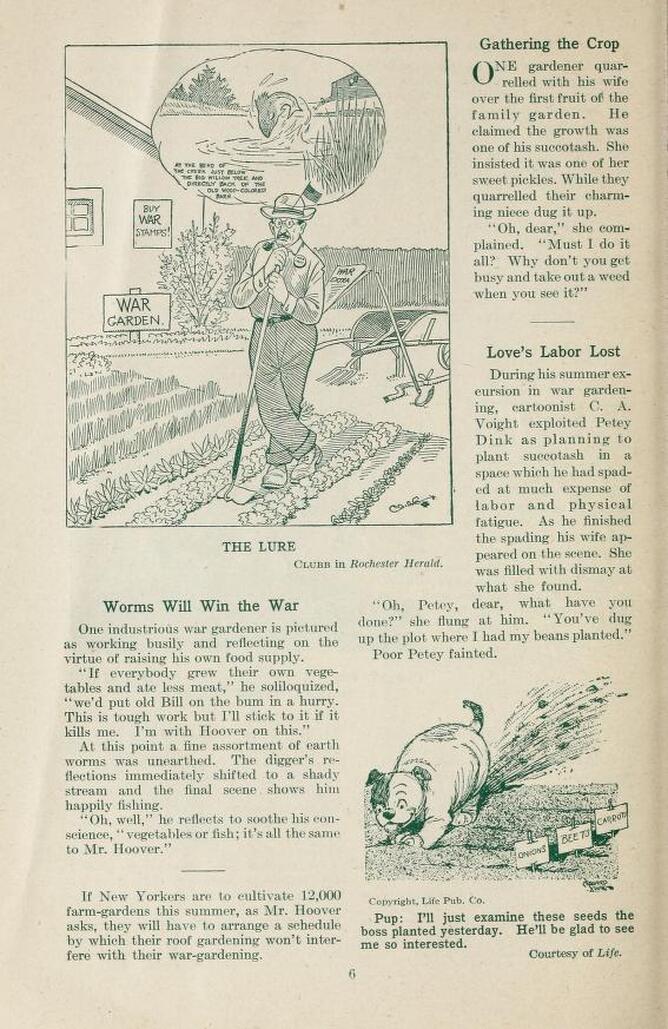

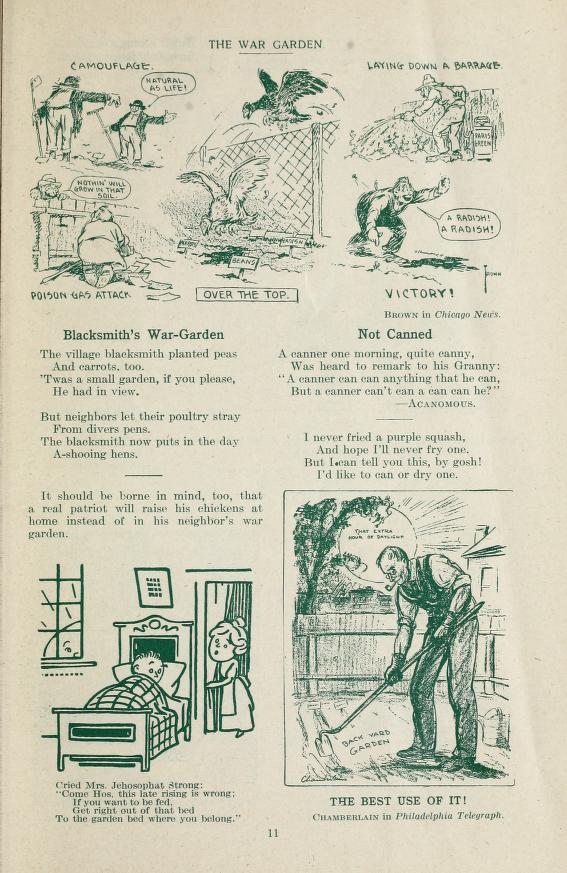

Although literal tons of snow have fallen across the United States in the past week or so, it's still beginning to feel like spring, which for many of us means our thoughts turn to gardening. If you know anything about World War II, you've probably heard of Victory Gardens. But did you know they got their start in the First World War? And the popularity of "war gardens" as they were initially called, is largely thanks to a man named Charles Lathrop Pack. Pack was the heir to a forestry and lumber fortune, and pumped lots of his own money into creating the National War Garden Commission, which promoted war gardening across the country, along with food preservation. They published a number of propaganda posters and instructional pamphlets. Today's World War Wednesday feature is another pamphlet, but its primary audience was not the general public, but rather newspaper and magazine publishers! Full of snippets of poetry, jokes, cartoons, and articles published by newspapers and magazines around the country, even the title was a bit of a joke. "The War Garden Guyed" is a play on the words "guide" and the verb "guy" which means to make fun of, or ridicule. So "The War Garden Guyed" is both a manual to war gardens and also a way to make fun of them. In the introduction, the National War Garden Commission (likely Charles Lathrop Pack himself), writes: "This publication treats of the lighter side of the war garden movement and the canning and drying campaign. Fortunately a national sense of humor makes it possible for the cartoonist and the humorist to weave their gentle laughter into the fabric of food emergency. That they have winged their shafts at the war gardener and the home canner serves only to emphasize the vital value of these activities." Each page of the "guyed" has at least one image and a few bits of either prose or poetry. The below page is one of my favorites. In the upper cartoon, an older man leans on his hoe in a very orderly war garden. His house in the background features a large "War Garden" sign and a poster saying "Buy War Stamps!" In his pocket is a folded newspaper with the headline "War Extra." But he is dreaming of a lake with jumping fish and the caption - indicating the location of the best fishing spot. The cartoon is called "The Lure" and demonstrates how people ordinarily would have been spending their summers. In the lower right hand corner, a roly poly little dog digs frantically in fresh soil. Little signs read "Onions, Beets, Carrots." The caption says "Pup: I'll just examine these seeds the boss planted yesterday. He'll be glad to see me so interested." Another article on the page is titled "Love's Labor Lost." It reads: "During his summer excursion in war gardening, cartoonist C. A. Voight exploited Petey Dink as planning to plant succotash in a space which had had spaded at much expense of labor and physical fatigue. As he finished the spading his wife appeared on the scene. She was filled with dismay at what she found. 'Oh Petey, dear, what have you done?' she flung at him. 'You've dug up the plot where I had my beans planted.' Poor Petey fainted." Many of the bits of doggerel and cartoons poked fun at inexperienced gardeners like Petey Dink. Pests, animals, digging up backyards and hauling water, the difficulty in telling weeds from seedlings, and finally the joy at the first crop. This page has a comic at the top that illustrates these trials and tribulations perfectly, through the lens of war. In the upper left hand corner, a sketch entitled "Camouflage" depicts a man who has just finished putting up a scarecrow who crows, "Natural as life!" as he poses exactly the same as his creation. Below, another called "Poison Gas Attack" depicts a neighbor leaning over the fence to comment "Nothin will grow in that soil" at a man kneeling in the dirt, a bowl of seed packets and a hoe on either side of him. The title implies that the neighbor is full of hot air and poison. The center scene, titled "Over the Top," shows a pair of chickens gleefully flying over a fence to attack a plot marked "Carrots," "Beans," and "Radishes." In the top right-hand corner, in a sketch titled "Laying Down a Barrage," a man with a pump cannister labeled "Paris Green" is spraying his plants. Paris Green was an arsenical pesticide. And finally, in one labeled "Victory!" a man gleefully points to a small seedling in an otherwise empty row and cries, "A radish! A radish!" In a bit of verse called "Not Canned" reads: A canner one morning, quite canny, Was heard to remark to his Granny: "A canner can can anything that he can, But a canner can't can a can can he?" And finally, apt for this past weekend's Daylight Savings Time "spring forward" is an evocative sketch depicts a man hoeing up his back yard garden while a large sun shines brightly and reads "That extra hour of daylight." The sketch is captioned, "The best use of it!" "The War Garden Guyed" has 32 pages of verse, doggerel, short articles, and cartoons. Charles Lathrop Pack was correct when he said the newspapers evoked "gentle laughter" as none of the satirical sheets actually discourage gardening. Indeed, most of the text is directly in line with the propaganda of the day promoting the development of household war gardens and the movement to "put up" produce through home canning and drying. Many of the cartoons directly connect to the war itself, comparing fighting pests to fighting Huns, pesticides to ammunition and "trench gas," and equating canning and food preservation efforts with vanquishing generals. What the booklet does do is poke fun at all of the hardships and difficulties first-time or inexperience gardeners would face. Stray chickens, cabbage worms and potato beetles, dogs and children, competing spouses, naysaying neighbors, post-vacation forests of weeds, and trying desperately to impress coworkers and neighbors with first efforts. War gardens were no easy task, and there were plenty of people who felt that they were a waste of good seed. But Pack and the National War Garden Commission persisted. They believed that inspiring ordinary people to participate in gardening would not only increase the food supply, but also free up railroads for transporting war materiel instead of extra food, get white collar workers some exercise and sunshine, and provide fresh foods in a time of war emergency. How successful the gardens of first-year gardeners were is certainly debatable. But in many ways, war gardens were more about participating than food. After the war, Pack rebranded his "war gardens" as "victory gardens," asking people to continue planting them even in 1919. The idea struck such a chord that when the Second World War rolled around two decades after the first had ended, "victory gardens" and home canning again became a clarion call for ordinary people to participate in the war on the home front. The full "War Garden Guyed" has been digitized and is available online at archive.org. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

This is one of the more famous food-related posters of the First World War. Created by famous illustrator and artist James Montgomery Flagg, "Sow the Seeds of Victory," and its sister poster (below) "Will you have a part in Victory?" were both produced by the National War Garden Commission, headed by Charles Lathrop Pack. The bottom of each poster reads "Every Garden a Munition Plant" with instructions in the lower right-hand corners reading "Write to the National War Garden Commission - Washington, D.C. for free books on gardening, canning, & drying." The posters both feature the same image - the United States embodied as Columbia, striding boldly, sandaled feet marching through a freshly plowed field, and broadcasting seed from a round basket. Columbia wears her Classical-style dress in the colors of the American flag - red, white, and blue - and wears a Phyrgian cap on her head, a symbol of freedom and liberty. The poster implies that by planting gardens, ordinary Americans could "Sow the seeds of Victory" and "plant and raise your own vegetables" - helping the war effort both literally and symbolically. Although "Every Garden a Munitions Plant" is a bit on the nose, the martial language helped reinforce the importance of growing vegetables at home, rather than consuming fuel and war materiel by purchasing vegetables grown far away, or canned commercially. The phrasing of the first poster is more in line with the sentiment of the image, and was likely the first produced. "Will you have a part in Victory" implies that the viewers may have already seen the first poster and understand its original intent. The Library of Congress estimates that these posters were produced in 1918, which is entirely possible, but the National War Garden Commission had instructional booklets on gardening, canning, and drying all published in 1917. Given that the NWGC was one of the first organizations to advocate for war gardens, even before the outbreak of war, so it is possible these are from 1917. Ironically, James Montgomery Flagg helped hasten the demise of Columbia as a symbol of the United States. His depiction of Uncle Sam, first featured on the July 6, 1916 cover of Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper asking "What are YOU doing for Preparedness?" - he later repurposed the image, inspired by Britain's Lord Kitchener, into the infamous "I Want YOU" Army recruitment poster, which was so effective it was recycled for the Second World War. By the 1930s, Uncle Sam (and his feminine counterpart, Aunt Sammy) had completely superseded Columbia as a symbol of the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! As I delve deeper into research on the farm labor shortage for my book, I'm starting to realize that the main theme of the home front in the First World War is that there were a whole bunch of people doing largely the same thing at the same time, and it wasn't until really the end of 1917 into 1918 that government agencies figured things out enough to actually get everyone properly organized. This poster is just one example of that. "We Eat Because We Work," a poster featuring cherubic White children digging and watering what are presumably radishes (judging by the contents of the basket) on a sunny hillside overlooking a flag flying not the American flag, but one of the United States School Garden Army, reads a little more ominously in the context of say, Nazi Germany, or Orwell's 1984. But when the U.S. School Garden Army was founded, and likely when this poster was produced, terms like "dictator" and "propaganda" had far more innocent meanings. Still, this poster does seem to imply, consciously or not, that children who do NOT work, will NOT get to eat. I doubt it was meant that way. Instead, like many propaganda posters of the First World War, it was meant to inspire people to participate. This poster sent me down the rabbit hole a bit, in part because the online history of The United States School Garden Army was so vague, and I'm a stickler for exact dates. Rose Hayden-Smith has written about the United States School Garden Army, but even she isn't super clear on when exactly the "army" was founded. The Farm Cadet program, which literally "enlisted" high school-aged boys into farm work on military-style camps, was founded in New York State in April of 1917, just days after the United States entered the war. A May 5, 1917 article in the New York Times mentions the "National School Children's Garden League," but only to mention a fundraiser for the league. It's the only reference I've been able to find of that organization. By June, 1917, Port Jervis, NY is discussing school gardens in conjunction with the Farm Cadet program, but school gardens as pedagogy had been popular throughout the Progressive Era. It seems that despite claims online that the United States School Garden Army was founded in 1917, it wasn't until March of 1918 that the USSGA was official. The Newburgh, NY Daily News published "Millions of Children to Enlist in Nation's School Garden Army" on March 20, 1918. The article suggests that this is a brand new endeavor, mentioning several times that this "new army" and "plans" "will begin soon." The "draft" age for the United States School Garden Army was 9-16 years old, both boys and girls. The cut-off age of 16 was so that boys aged 16 and older could participate in the Farm Cadet program. This poster features children who look younger than nine years old, but perhaps young cherubs were more attractive models than gangly pre-teens. As Hayden-Smith argues, the United States School Garden Army was designed to turn children from consumers into producers, at least temporarily. Critiques of the use of child labor were assuaged by assurances that the work would be for no more than a few hours a day, and always supervised by teachers or other staff. The work of the USSGA continued for several years after the war, still going strong in 1919 and 1920, likely because the High Cost of Living was keeping food prices up, and school gardens raised produce to be consumed by students on site, thus lowering school cafeteria costs. In fact, most of the articles from late 1919 and early 1920 talk about the financial benefits of the school gardens, in addition to the social and emotional benefits. In today's context, the discussion of the financial benefits of child labor seems mercenary, at best, but the school garden movement did have social and emotional benefits as well - being out-of-doors, the "stick-with-it-ness" of tending living things, and the rewards of getting to eat the results of your hard work. School garden programs that help provide for school cafeterias have been revived in recent years as a way to engage students with "real" food and create affordable access to fresh, local fruits and vegetables, especially in areas of food deserts. But growing school gardens isn't cheap, nor is it easy. In much of the nation, the best garden growing months are when school is not in session. In World War I, teachers and students gave up part or all of their summers for the war effort. In today's world, the garden manager usually does the bulk of the work over the summer. Regardless, the work of school gardens during the First World War does seem to have been a relative success. As I research more, I'll delve deeper into school gardens, so stay tuned! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! When it comes to modern ideas about Victory Gardens, there's a lot of romanticism and rose-colored glasses. Hearkening back to a kinder, gentler time when everyone pulled together toward a common goal and had delicious, organic vegetables in their backyards while they did it. But the reality was often much different from our modern perceptions. This propaganda poster is a good example of that. "Shoot to kill!" it says - "Protect Your Victory Garden!" In it, a woman wearing blue coveralls and a wide-brimmed hat, a trowel in her back pocket, sprays pesticide on a large, green insect (a grasshopper?) taking a bite out of an enormous and perfectly red tomato. She is protecting her victory garden from the "fifth column" of insect predation. "The Fifth Column" was a term used in the United States to describe sabotage and rumor-mongering by foreign spies. In this instance, insects become the "fifth column" because the act of eating crops threatens wartime food supplies, and is therefore sabotage by a foreign enemy. The food supply had to be protected and maximized at all costs. Anxieties around food supplies, especially in the winter when commercially produced foods might be scarce, meant that victory gardens took on special urgency. For the first time in at least a generation, Americans were having to put up their own food to help them get through the winter. And making every quart count was only possible if the garden did well. Lots of militarized language was used in propaganda concerning food, but none as war-like as the battle against pests in the victory garden. The idea that gardening before the 1950s was all organic is a common misconception. Even prior to the First World War, farmers and even some gardeners were dusting their crops with Paris Green and London Purple. Paris Green was a bright green toxic crystalline salt made of copper and arsenic. London Purple was calcium arsenate - normally white, but also a byproduct of the aniline dye industry, and was therefore sometimes tinged purple. Along with arsenate of lead, another salt, these three were termed arsenical pesticides and were used often in agriculture. The arsenic in rice scare from a few years ago was likely due to elevated levels of arsenical pesticide residue in the soil. Especially since rice from California, which first began to be commercial produced in 1912, but was not widely available across the country until the 1960s. That late adoption of rice agriculture meant that production was not as exposed to arsenical pesticides as elsewhere in the U.S. In 1944, the USDA published "A Victory Gardener's Handbook of Insects and Diseases" that identified common pests and suggested remedies. Calcium arsenate and Paris green were recommended (albeit with warnings about arsenic residue), along with:

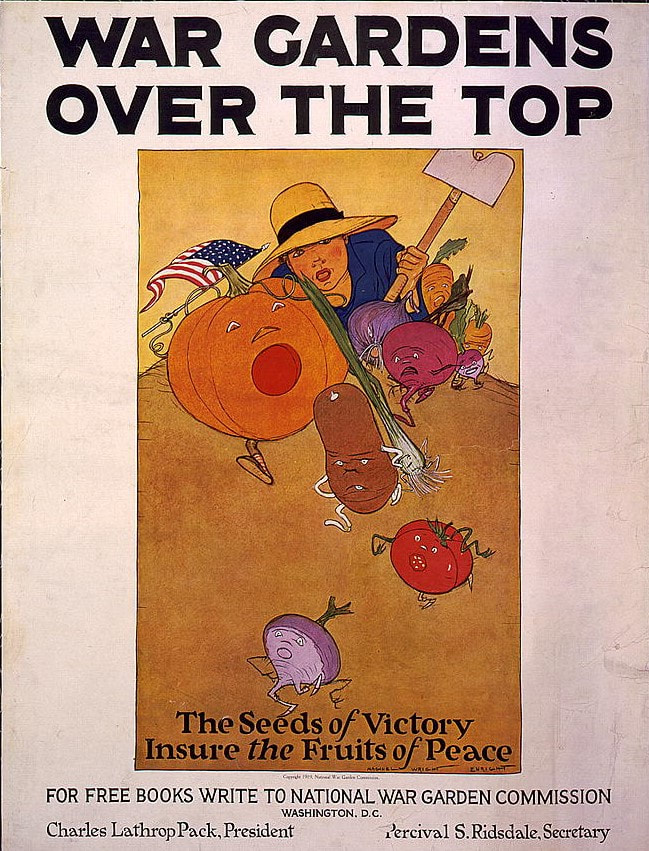

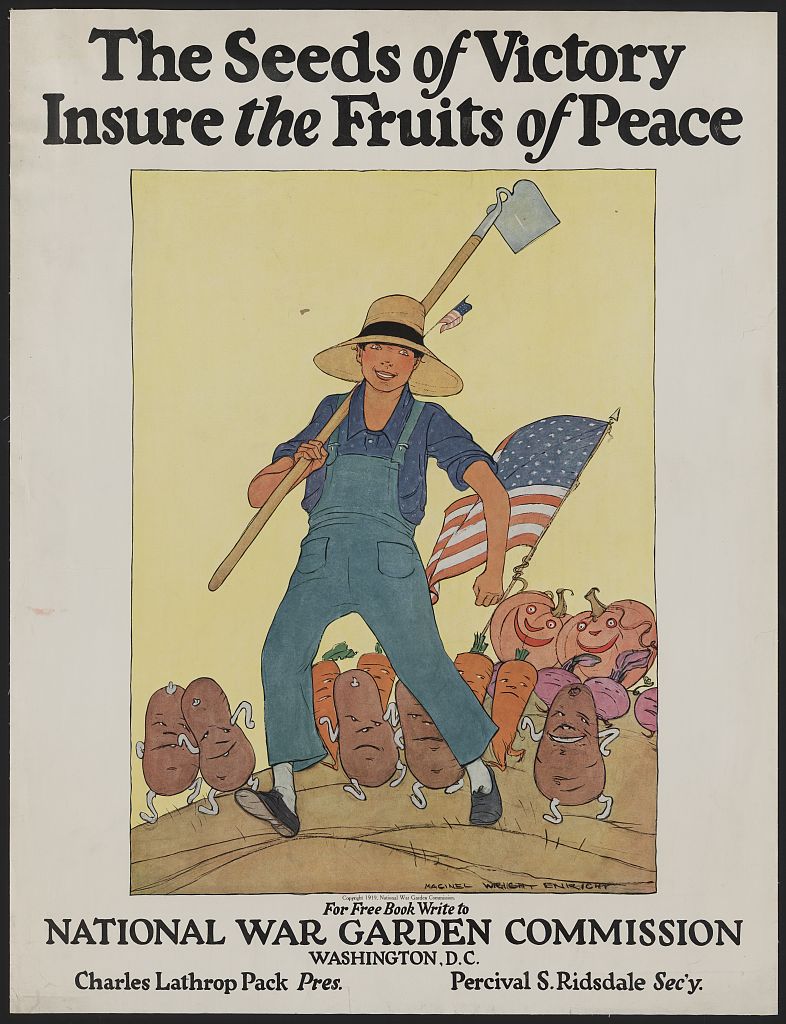

Although some people may have chosen not to purchase pesticides, likely due to expense more than concerns about poisoning, the emphasis on the danger pests posed to the general food supply continued. Hand atomizers, which is what the hand sprayer in the propaganda poster is called, were frequently depicted in print and even on film. Despite USDA warnings about application safety, no one is ever seen applying the highly toxic, aerosolized liquid pesticides with protective equipment. However, the science of the effects of exposure to toxic chemicals was not yet well-studied. DDT, invented in 1939, was deemed a miracle chemical and helped dramatically reduce diseases like malaria and water-borne bacteria that in previous wars had sometimes killed more soldiers than the conflict itself. Because soldiers faced no immediate effects, the chemical was deemed safe, and used everywhere from farms to a treatment for lice in children. But like the arsenical pesticides, the effect was cumulative, and it wasn't until Rachel Carson's 1962 Silent Spring that Americans began to wake up to the dangers of pesticides. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! The National War Garden Commission, a private organization funded by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, was one of the most prolific sources of wartime propaganda posters outside the federal government. One of the major proponents of civilian garden programs, even before the U.S. entered the First World War, the National War Garden Commission gave away free booklets on gardening, canning, and food preservation. The above poster features a boy with a spade and straw hat climbing over a mound of dirt. In the lead are series of anthropomorphic vegetables, including a pumpkin carrying the American flag, and all appear to be yelling or screaming as they run down the hill. Reading "War Gardens Over the Top," and "The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace," the poster brings to mind the "boys" going "over the top" of the trenches in battle. This use of military language in propaganda posters was not uncommon, but this particular phrase likely did not have the full impact in the period that it does now. Today, we realize how horrific the charges of men "over the top" and across no-man's land between the trenches on the front really were. But in the period, it's likely people had only sanitized newspaper articles and perhaps a propagandized newsreel or two to give them a frame of reference for the term. In this second poster, which also reads "The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace," our military allusions are a little more innocent. Here our same overall-ed and straw-hatted boy marches in a parade, hoe over his shoulder, accompanied by more anthropomorphized vegetables. These vegetables look less than thrilled to be marching, but the sentiment is the same. Both posters were published in 1919, technically AFTER the war was over. But as with most wars, the end of conflict does not mean that everything goes back to normal. There were numerous attempts by a number of organizations, including the federal government, to get Americans to continue to conform to wartime measures, including voluntary rationing and war gardens, which were termed victory gardens after the cessation of hostilities, well in to 1919 and even 1920. Here, the National War Garden Commission makes the argument that the "seeds of victory insure the fruits of peace," meaning that by continuing to plant vegetable gardens and free up domestic food supply for shipment overseas, Americans could help stabilize and rebuild Europe in the wake of the war. Illustrated by Maginel Wright Enright, primarily known as a children's book illustrator, the posters have a luminous clarity, even if Enright was not particularly good at giving vegetables convincing facial expressions. Lots of folks are starting year two of pandemic gardens - are you one of them? I am! Raised beds are going in this year and I already have my seeds and a plan. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

George Washington Carver is a historical figure you may have heard of. Perhaps you grew up learning in elementary school that he invented peanut butter (he didn't), or perhaps you know his work in popularizing sweet potatoes. You might know he was born into slavery, and through his pioneering efforts at plant science, helped found the agricultural college at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

But the bulk of his accomplishments have been glossed over in popular culture, until now. Grist recently published an excellent overview of the real contributions Carver made, and why they have largely been ignored. George Washington Carver died on January 5, 1943. Just a few months before his death, he published Nature's Garden for Victory and Peace, his contribution to the victory garden conversation during the Second World War.

Many people wrongly attribute Carver's booklet as a guide to victory gardens. In fact, it is a guide to foraging, and in line with Carver's ideas about food sovereignty that were decades ahead of their time.

Carver knew that access to land meant access to food, and even if Black families were denied access to land to grow gardens, they could forage in the wild public spaces or unclaimed verges of roads, edges of fields, etc. Still coming out of the Great Depression in 1941, people were eager to supplement often meager food supplies however they could. Free food was worth the labor to collect and process it. Nature's Garden lays out not only the common and botanical names of many wild-growing and native greens and herbs, some with accompanying line drawings, but also advice for harvesting and processing, recipe suggestions, and advice on drying garden produce for long-term storage - cheaper and easier than canning, which required expensive equipment and jars. Carver also includes references to Indigenous food uses, such as the use of sumac in making "lemonade," and directions for how to make "Lye Hominy," using the nixtamalizing process invented by Indigenous peoples in Mexico to hull corn and make the naturally-occurring niacin in the corn absorbable by the human body. The booklet was given away free - one copy per person. Additional copies could be acquired at the cost of printing. A Simple, Plain, and Appetizing Salad

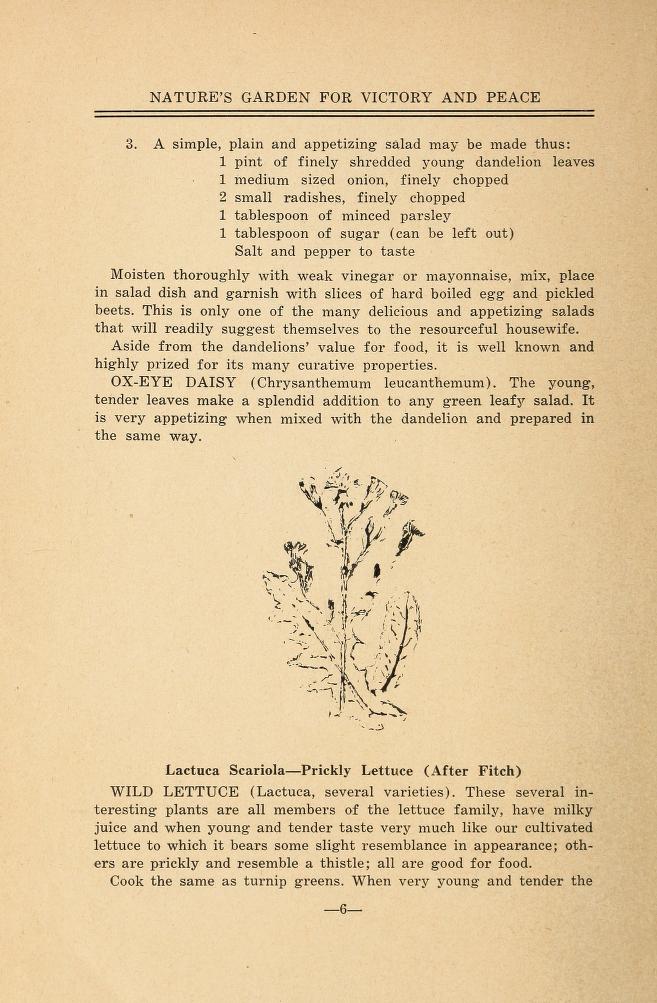

One of the few recipes Carver actually outlines in Nature's Garden is also one of the first - a recipe for dandelion salad.

It reads: "A simple, plain and appetizing salad made be made thus: 1 pint of finely shredded young dandelion leaves 1 medium sized onion, finely chopped 2 small radishes, finely chopped 1 tablespoon of minced parsley 1 tablespoon of sugar (can be left out) Salt and pepper to taste "Moisten thoroughly with weak vinegar or mayonnaise, mix, place in salad dish and garnish with slices of hard boiled egg and pickled beets. This is only one of the many delicious and appetizing salads that will readily suggest themselves to the resourceful housewife." A modern incarnation might be made with arugula, instead of dandelion leaves, if you are unable to forage your own safely.

Today, other foragers are trying to reclaim foraging for BIPOC communities. Alexis Nikole Nelson, also known as Black Forager, is one of those people. Like Carver, she reminds everyone that foraging has been the purview of BIPOC communities for as long or longer than the white male foragers who often get all the attention these days.

I love Alexis' near-daily posts and how she cooks the food she forages - the most important information and often left out of the foraging equation. She's been profiled by TheKitchn, and Civil Eats, but you can learn the most by just following her on Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, or Facebook. You can also support her work by becoming a patron on Patreon! Further Reading

To learn more about George Washington Carver, check out these excellent resources.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

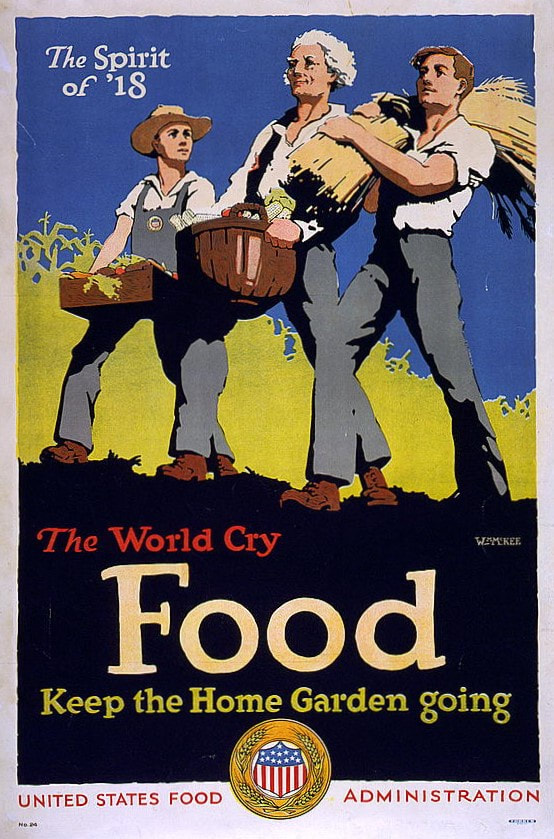

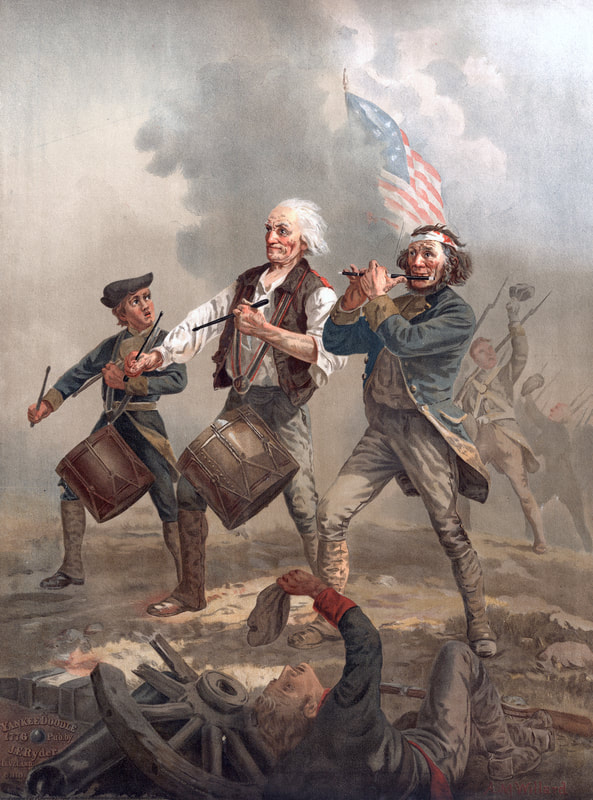

Last week we featured a propaganda poster from World War II that hearkened back to Valley Forge. This week we're featuring a propaganda poster from World War I that also hearkened back to the American Revolution - "The Spirit of '18." During the First World War, the United States Food Administration, along with private organizations like the National War Garden Commission, encouraged ordinary Americans to plant war gardens (later termed "victory gardens," a name that stuck when revived in the Second World War). War gardens were needed to free up commercial agricultural products to send overseas to American Allies, many of whom were suffering after three years of privations, and to feed American troops abroad. In particular, the 1915 and 1916 wheat harvests had been poor, leaving little to export. In order to free up domestic supplies for shipment overseas, the government encouraged Americans to grow and preserve more of their own food, alleviating the domestic strain on food supplies and freeing up commercial foods for government use. This was a tactic which was revisited during World War II. In this poster, a young boy wearing overalls bearing the US Food Administration seal, carries a wooden crate of vegetables. He looks on at the older man in the center, whose haircut brings to mind George Washington, and who carries a larger basket of produce. At the far right, a young man carries a sheaf of wheat on his shoulder. All are marching in step, a stylized cornfield and a brilliant blue sky behind them. "Spirit of '18," the poster reads at the top. Below, it says, "The World Cry Food - Keep the Home Garden Going," with the United States Food Administration title and seal at the bottom. Although it doesn't seem like it on the surface, this poster references the American Revolution. It is based on a very famous image which would have been familiar to Americans at the time. Painted by Archibald MacNeil Willard in 1875 for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the painting which became known as "Spirit of '76" was revealed to little critical acclaim, but great popularity among ordinary people. Willard reproduced it several times. The original was enormous - eight feet by ten feet. The above image of "Spirit of '76" is a chromolithograph produced by J. E. Ryder for the Centennial Exposition and sold to tourists as a souvenir (see the original here). This helped its popularity greatly, as it was widely panned by critics as too dark. The painting illustrates two drummers - one elderly and one a young boy, accompanied by a wounded man playing fife - behind them flies the American flag (or perhaps the Cowpens battle flag) and more troops waving their tricorn hats - evoking perhaps that the resolute fife and drum corps are leading a column of relief troops, bringing victory to the battle that wounded the artilleryman in the foreground with his cannon on the ground, its carriage broken. You can see how closely William McKee mirrored the work of Archibald Willard - the three figures in both images are nearly identical - a young boy, an elderly man, and a young man, although in the World War I poster the young man is considerably younger and more Adonis-looking than Willard's figure. The figures represent the three generations - youth, adulthood, and old age, as well as the breadth of men participating in the American Revolution and World War I. During the Revolutionary War, musicians were usually boys too young and men too old to enlist as regular soldiers. Old men and young boys were also "drafted" during the First World War for home front duties, including gardening and farm labor. In both images, the figures are marching forward, bringing victory behind them. Archibald Willard died on October 11, 1918, exactly one month short of the end of World War I. So it is possible he saw his work replicated in this poster. "Spirit of '76" was his most popular and enduring work, but it did not bring fame or fortune. For other Americans who saw the "Spirit of '18" poster, it surely would have instantly brought to mind the "Spirit of '76," and the sacrifices and courage of the American Revolution, inspiring similar levels of patriotism and sacrifice by Progressive Era Americans during the First World War to "do their bit" and contribute to the war effort through war gardens. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed