|

In an effort to cope with COVID-19 and all the shelter in place orders out there across America, I decided to host a Food History Happy Hour, live on Facebook! I'll be hosting these each Friday evening at 8 PM eastern standard time for anyone who wants to join.

I'll make a historic cocktail - alcoholic or non-alcoholic - live on the air, and then take questions related to food history! I can't always promise I'll know the answer every time, but that's what my trusty phone is for - googling.

This week I made a Hoffman House Fizz, from the Hoffman House Bartender's Guide, published in 1912.

Hoffman House Fizz Recipe Juice of half a lemon 1/2 teaspoonful powdered sugar 1 jigger Plymouth gin 1 teaspoonful cream Shake well. Pour into glass simultaneously with seltzer (I used lemon-lime) and drink while effervescent. This was a surprisingly refreshing beverage. Please note that Plymouth gin is sweeter and mellower than the typical London Dry Gin. I used American gin, Bluecoat brand, which is similarly sweeter and mellower. I did feel it needed a bit more cream to temper the acidity of the lemon juice - I would add a tablespoon or more next time. A smidge more sugar (a full teaspoon) would probably also temper the lemon juice a bit. In all, I would probably drink this again. Thanks again to everyone who joined for the livestream and I hope to see more of you next week, when I'll be doing a historic beverage based on cranberry juice and we'll talk about cranberry scandals! See you then!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

0 Comments

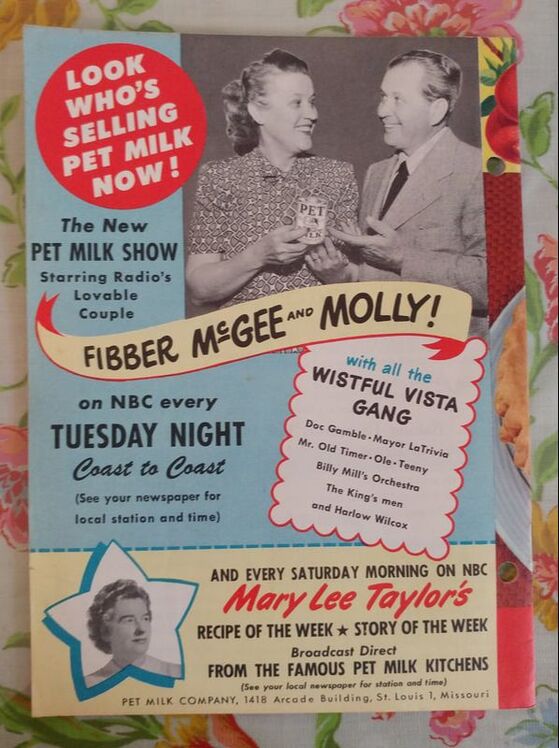

One of the wonderful things about being a food historian is not only tracking down and finding wonderful historic and vintage cookbooks for my personal collection, but people also give me vintage cookbooks! This was part of one such gift: a rather large selection of Mary Lee Taylor PET cookbooklets. For those of you not familiar with it, PET is a brand of evaporated milk. First produced in Illinois in the 1880s, PET milk made a name for itself supplying soldiers during the Spanish American War and again in World War I. But following the war, production ratcheted down, and PET was known to be in trouble.

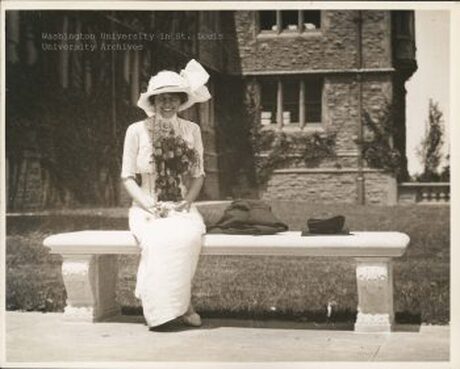

The 1920s and '30s were a time of advertising innovation and one woman stood out amongst the crowd. Erma Perham Proetz was born in Denver, Coloradio in 1891. After graduating from Washington University and marrying Dr. Arthur Proetz, the couple settled in Saint Louis, MO, where Erma started working in the advertising business, as a copy editor for the Gardner Advertising Company. In 1923 she was assigned to the PET Milk Company account. The company had been foundering after World War I. In 1924 she won the Harvard Advertising Award for distinguished individual advertisements, with its accompanying $1,000 award. In 1925 she took the award again, this time for the best use of both text AND illustration for the PET milk campaign. In 1927 she received the $2,000 Edward W. Bok prize by the Harvard Award Jury for the best planned and executed national advertising campaign for a single product - PET milk. She was the first person to ever win the Harvard Advertising Award three times. In 1930, she was made a director of the Gardner Advertising Company - just seven years after starting as a lowly copy editor.

Erma's true brilliance, however, was the idea of Mary Lee Taylor.

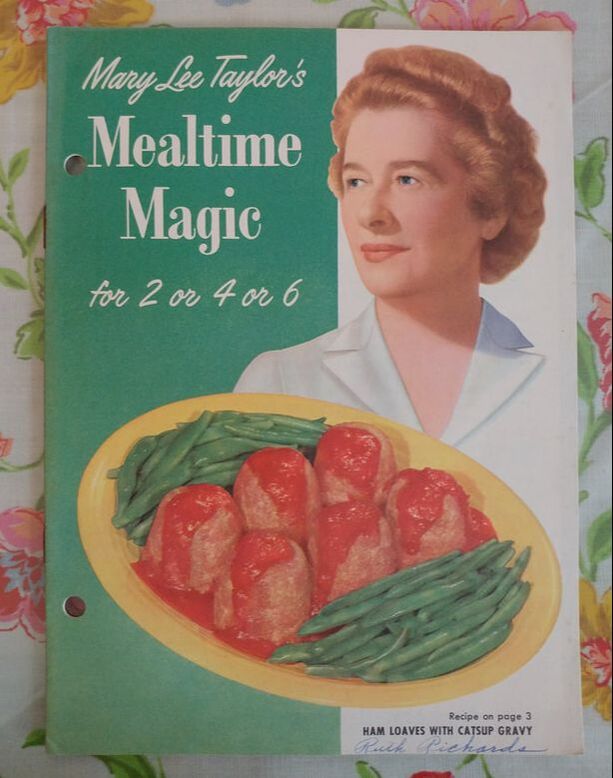

Mary Lee Taylor was a pseudonym for Erma (although whether or not they were one and the same is debated). Although Erma remained at the Gardner Advertising Company and eventually became an executive, she wrote for/as Mary Lee Taylor for the rest of her career. Taylor embodied the kind, chatty, experienced home economists that housewives had come to trust by the late 1920s. Combining all of the best advertising opportunities at the time, Erma put Mary Lee Taylor to work in print, including newspapers, magazines, and cookbooklets. Dozens of Mary Lee Taylor cookbooklets were published over the years, and I am lucky enough to have a good chunk of them.

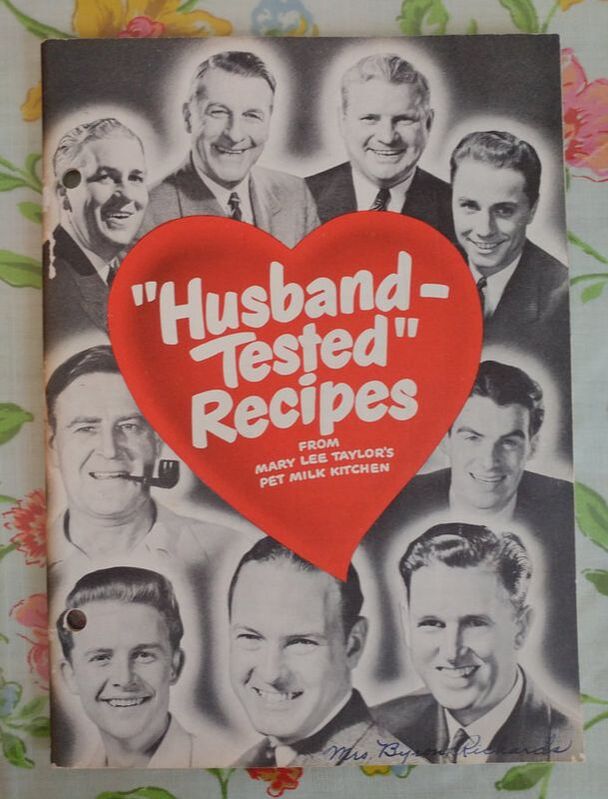

Unfortunately, particularly with the summer themed ones, there is a fair amount of recipe repetition. And, of course, every single recipe uses PET evaporated milk! But there are some particularly fun favorites, including "'Husband-Tested' Recipes."

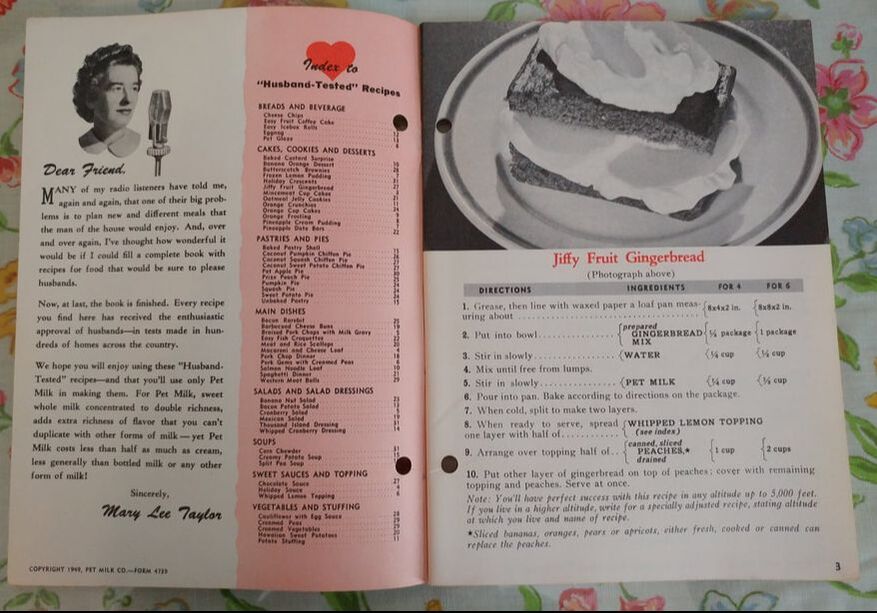

But as you can see from her little "Dear Friend" letter above, Mary Lee Taylor was probably best known for her radio show.

In the 1920s radio was still a fairly new medium, but mass production made radio sets more accessible to a wide range of Americans. It was a popular way for companies to advertise and product placement and corporate-sponsored shows soon became commonplace. Begun in 1933, the Mary Lee Taylor Show first aired on CBS and was one of the longest running cooking shows ever, ending in 1954. On CBS the show was just 15 minutes long, and featured a weekly recipe from Proetz as well as household tips, all using PET milk.

Erma was a member and leader of many women's and advertising groups, including the Women's Advertising Club of St. Louis, the St. Louis Branch of the Fashion Group, and the Council of Women's Clubs of the Advertising Federation of America. In 1935, Fortune Magazine named her one of 16 Outstanding Women in Business. In 1938, she attended the 34th annual convention of the Advertising Federation of America in Detroit, MI. An Associated Press article quoted her in a discussion about women in advertising. They wrote, "Ms. Erma Perham Proetz of St. Louis, a member of the Federation board, advised women hoping to enter advertising to take a home economics course, and to obtain some training in writing. 'The field is limitless,' she said."

And for Erma, it was limitless. She died on August 7, 1944 "after a long illness," and although her obituary is quite short, she had been executive vice president of the Gardner Advertising Company at the time of her death. That same year, the St. Louis Fashion Group, of which she had been regional director, announced the establishment of an Erma Proetz Memorial Scholarship at her alma mater - the Washington University School of Fine Arts "in recognition of her great interest in students and the wide help and encouragement she gave many young girls starting out on their careers."

In 1945, the Women’s Advertising Club of St. Louis established an annual Erma Proetz Award for the most outstanding creative work done by women in advertising. This award was dedicated Erma's memory as she "stood for the highest standards of advertising and whose faith in the ability of women in advertising was well known throughout the country."

In 1948 the Mary Lee Taylor Show moved to NBC, known as "Mary Lee on NBC" and was expanded to 30 minutes, with a serial drama between "Sally and Jim," a young couple. The show ended with the long-running recipe of the week and the creative addition of "Today's Recipe for Happiness," which included warm wisdom about family and life from Mary Lee herself.

Although Mary Lee Taylor did survive Erma by several years, but she couldn't quite make the transition from radio to the new medium of television. In 1954, Mary Lee Taylor went off the air. Despite that fact, Mary Lee Taylor and Erma Perham Proetz both left a lasting legacy. In 1952, Erma was posthumously inducted into the Advertising Hall of Fame - one of only a very few women to ever receive that honor. And Mary Lee Taylor lives on in the remaining radio shows and cookbooklets that people like me love to collect.

If you'd like to listen to more of the surviving Mary Lee Taylor radio shows, you can do so, thanks to the kind people of the Old Time Radio Researcher's Group on the Internet Archive. Listen to the Mary Lee Taylor Show now.

Bibliography

Erma's Advertising Hall of Fame listing.

Washington University Archives and an online exhibit 6 Copywriting Takeaways From a Real Life Mad Woman "Advertising Prize Won By D.C. Man," Evening Star, February 23, 1926. "Advertising Men Open Convention," Evening Star, June 13, 1938. "Mrs. Erma P. Proetz Dies; Advertising Executive," Evening Star, August 8, 1944.

And, as always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

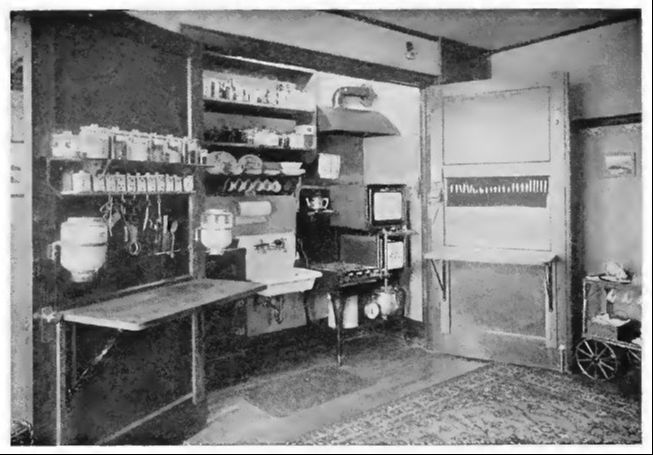

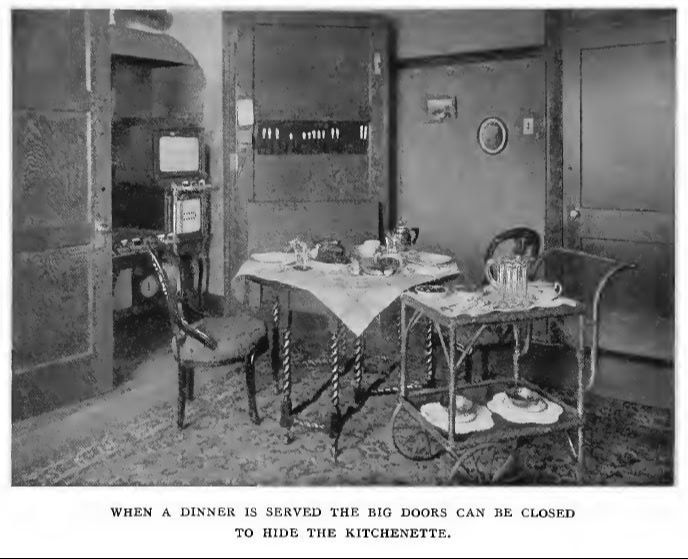

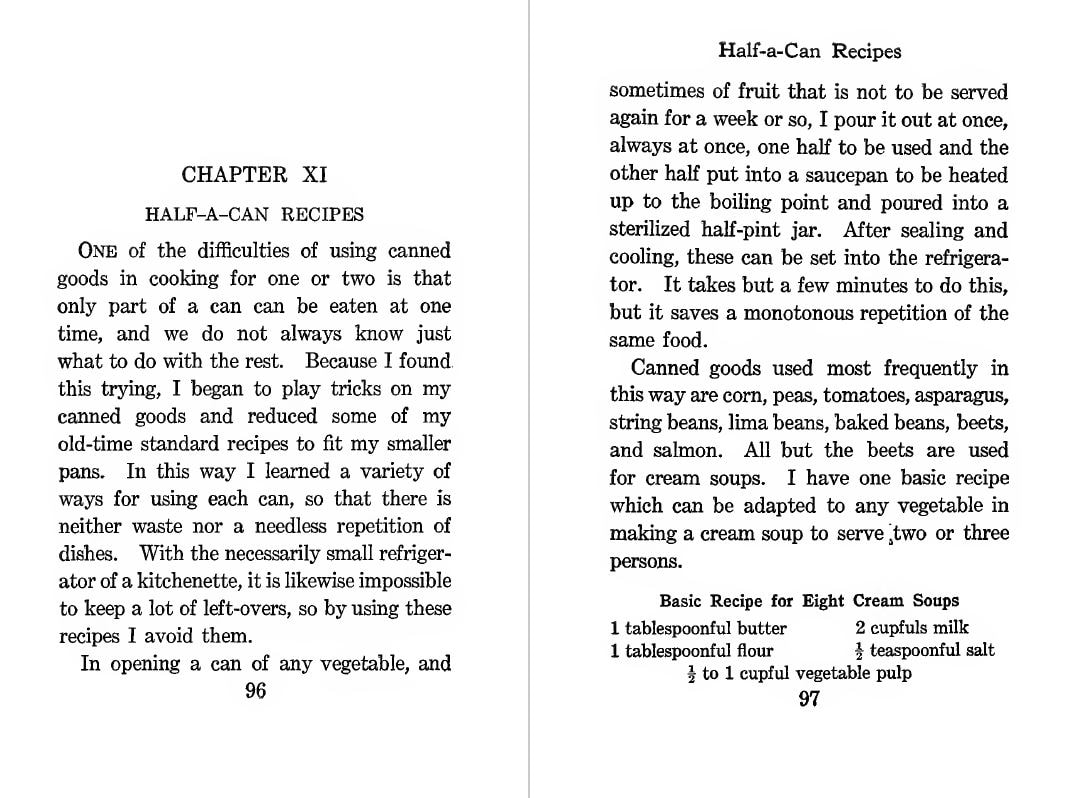

Friend and Patreon patron Anna Katherine posted the most fascinating article the other day. Architectural historian Sarah Archer (so many Sarahs in history work!) has written a great history of the Frankfurt Kitchen. What is the Frankfurt Kitchen, you may ask? Well, you'd be better off just reading the article, but to summarize briefly, it was invented by Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (1897–2000), who was helping to redesign apartment living in European nations recovering from bombing. Her kitchen was a model of efficiency based on the galley kitchens of railroad cars (although, it should be noted that the term "galley kitchen" was first used on ships). So why am I writing about this now? Because I've long had a fascination with the time of transition in American history when ordinary middle-class Americans had to shift from having live-in servants to doing their own work. And when "young brides" were thrown to the winds of married life with a high school or college education, but little idea of how to manage things on their own. Enter, "Kitchenette Cookery," by Anna Merritt East, originally published in May, 1917. I stumbled across Kitchenette Cookery on the Internet Archive (bless it forever), and it's a delightful snippet of life at the start of World War I (for the US, anyway). Anna Merritt East graduated from the University of Nebraska in 1912 and was, for a time, the "New Housekeeping Editor" for the Ladies' Home Journal. Unfortunately that's about all I can find out about her and "Kitchenette Cookery." The book really is designed for young women setting up a household for the first time, probably on a tight budget. Not only are the first chapters about setting up and kitting out the kitchenette, there are also two whole chapters on shopping and budgeting. But the recipe chapters are my favorites. "Breakfast on a Time Limit" talks about using the apartment building's hot water system to help hurry up coffee percolating and how to get a hot breakfast on the table in time for the husband to catch the "bus" to work. "High-Pressure Dinners" is a great deal about Anna's beloved pressure-cooker, with which she happily entertains guests who, of course, watch her cook in her tiny kitchen. The book itself is delightful from a historical standpoint, although sadly it has some rather poor reviews on Goodreads and elsewhere. Unlike many other books from the period, it has no real introduction to speak of, so sadly we get no real idea of where Anna's kitchen is, or if this is her real, everyday kitchen, although it appears so. Her kitchen, pictured above, is really just a closet with two very large doors. The door on the left serves as a sort of Hoosier cupboard, with flour storage/sifter, a folding wooden cutting board/work surface, and narrow shelves holding spices and what appear to be other baking supplies. Another folding wooden shelf lines the other door, with what appears to be an ingenious fabric pocket for silverware. Within the closet it an open shelf for dishes above the small sink, with what appears to be a roll of paper towels above. The tiny gas stove is at right and tucked into the corner by the front door (off frame at right) is a rolling tea cart. Here we see one door closed to illustrate how the kitchen can be closed off completely when time to dine at the tiny table, also folding. The tea cart is also in use for service. Although ingenious, this really is a "kitchenette" in the truest sense of the word - a kitchen in almost miniature, designed to provide the most basic functions. Although there is no floor plan for the whole apartment, it really must be either a one bedroom or studio. Apartments in large Eastern cities (this one is presumably in Boston) were often carved up out of former mansions or multi-level apartments (as they still are today), and thus were often cramped into small spaces not designed to be whole living quarters. This is another favorite chapter, in which Anna discusses the awful occurrence of having half a can of whatever - usually a vegetable - left over from making dinner for just two. Anna writes, "One of the difficulties of using canned goods in cooking for one or two is that only part of a can can be eaten at one time, and we do not always know just what to do with the rest. Because I found this trying, I began to play tricks on my canned goods and reduced some of my old-time standard recipes to fit my smaller pans. In this way I learned a variety of ways for using each can, so that there is neither waste nor a needless repetition of dishes. With the necessarily small refrigerator of a kitchenette, it is likewise impossible to keep a lot of left-overs, so by using these recipes I avoid them." My other favorite chapter (technically second-to-last, but seeming more apropos to be the end to this little blog post), is "A Bite to Eat at Bedtime," because who doesn't want a midnight snack these days? Her recipes mostly involve a lot of canned seafood, but I thought this fascinating little onion and cream cheese sandwich might actually be delicious, although serving with coffee is dubious - I think a cold beer or cider might be better. Of course, Anna was probably a good Prohibitionist, because as far as I can tell, there's nary a mention of wine or spirits in this little book. If you liked "Kitchenette Cookery" as much as I do, you can download the whole book from the Internet Archive. Funnily enough, my little kitchen (although MUCH bigger than Anna's) is a roomy galley kitchen. My little house was built about 1941 and out of bits of older houses (narrowboard floors and Victorian glass doorknobs, plus old-fashioned paned wooden windows, and a bluestone fireplace on a side porch), so the galley kitchen may have been inspired by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and her Frankfurt Kitchen! What is your kitchen like? Do you have an enormous roomy one? Or a tiny kitchenette like Annas? Let me know in the comments! And, as always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

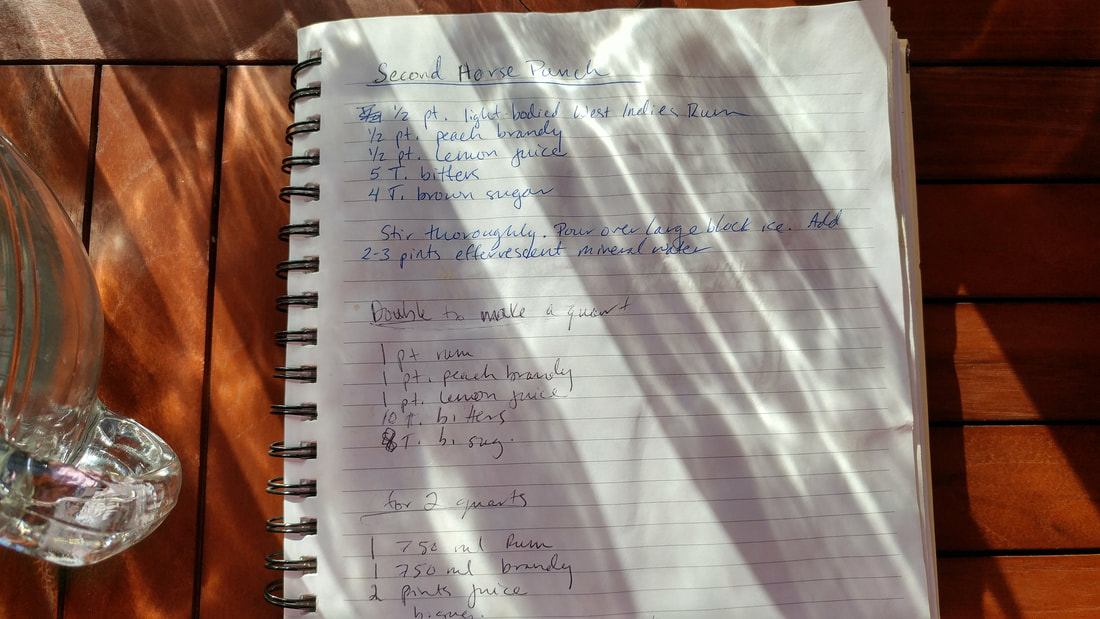

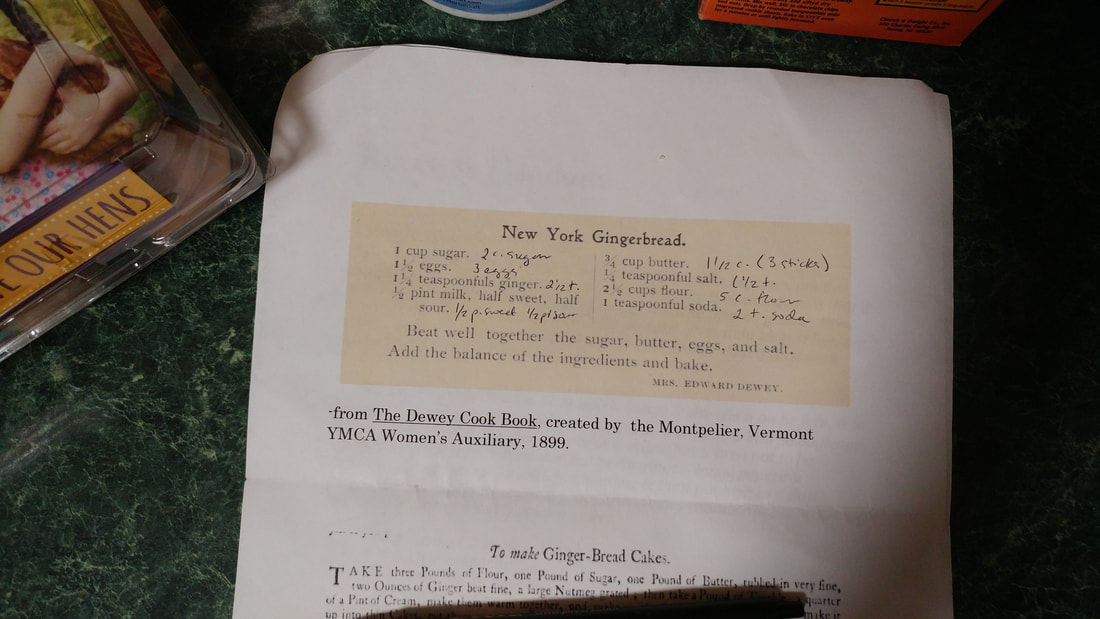

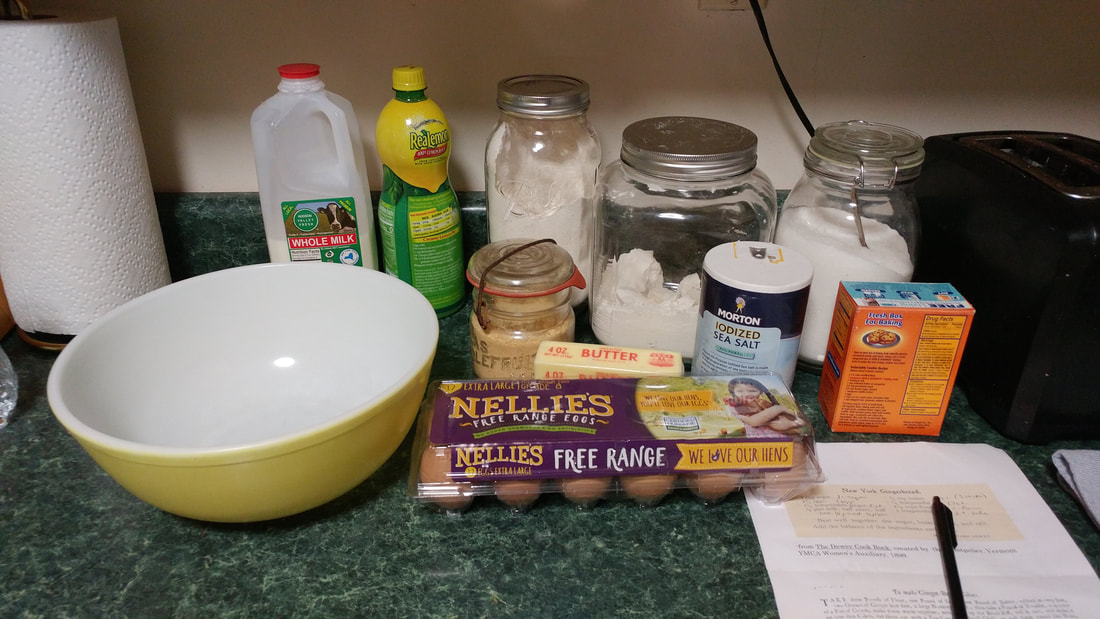

The more I learn about food history, the more I realize that our modern concept of seasonal eating is a big wrong-headed. I've often prided myself on my delight in seasonal eats and trying to stick to what is available seasonally in my cooking. Meaning, no strawberries in December or tomatoes in March or pumpkin in June. And this in-the-moment feeling certainly was quite historic, particularly in spring and summer as waves of produce came to be eaten. However, historic cooks did a great deal of preserving throughout the year, especially in preparation for the winter holiday season. From pickling young walnuts in June, making cherry bounce in July, and starting the holiday fruit cake in August or September, canning and drying weren't the only food preservation activities going on, and many happened year-round. Of course, I'm not much of a canner or jammer, and I find the easiest way to preserve involves alcohol. Even though (ironically) we don't do a great deal of drinking in our house, having something other than beer and wine at a party is delightful, and punch is one of the best ways to showcase an interesting beverage for a crowd. As some of you may be aware, we plan a huge holiday party every year (hosting between 20 and 40 people), and Second Horse Punch has been a staple since the beginning, starting 10 years ago. We got the recipe from a friend, who works at another 18th century historic site. The original recipe reads thusly: ½ pint light-bodied West Indies Rum (a.k.a. light Puerto Rican or Cuban) ½ pint peach brandy ½ pint lemon juice 5 tablespoons bitters (Angostura is about the only kind left and this recipe uses about half a bottle) 4 tabelspoons brown sugar Stir thoroughly. Pour over a large block of ice. Add 2-3 pints effervescent mineral water. So what's with the name? It was supposedly invented by the Second Lighthorse Brigade and a rusty stirrup added to the punch purportedly improved the flavor. We are ginger ale addicts in our house, and the added sweetness is very nice - I think if you used mineral water (or sparkling wine) as the original called for, you would taste the alcohol too much. And to be honest, the best Second Horse Punch goes down so smoothly you don't realize how much you've downed. Although our ratio is 1:2 Second Horse Punch to ginger ale, the gentleman who gave us the recipe does a 1:1 ratio. That's a bit too strong for us! The key to a good Second Horse Punch is to let it age. The longer, the better. At minimum three months, preferably up two years. The longer it ages, the smoother it becomes. But, if you're going to let it age for that long, be sure to store it in glass. Quart mason jars are fine, if you don't have bottles. Our first big batch is actually in an old green glass wine jug. Second Horse PunchHere is our quadrupled recipe, which makes 3 quarts (not two, like my handwritten recipe says - I've since corrected it). 1 quart white rum 1 quart peach brandy 1 quart lemon juice 16 tablespoons brown sugar 2 bottles angostura bitters (which is actually only 16 tablespoons, not 20, but that's okay) Mix well - I recommend adding the brown sugar first - and pour into glass jars for storage. Label with the date so you know when best to mix it up for a delicious, not-too-sweet, spicy, delicious party punch. If you don't want to make 3 quarts, you can cut the recipe in half and use a pint mason jar for your measuring (which I did, but twice, because I didn't have a big enough pouring bowl). To make the finished punch, mix one part Second Horse Punch with two parts ginger ale and serve in a big punch bowl over ice. But only after you've let it age in a dark, cool place for at least 3 months! If you make some now, it should be quite nice by Christmas. And, as always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. A few weeks ago my fellow food historian Niel De Marino gave a wonderful talk on Christopher Ludwick, an 18th century German immigrant to Philadelphia who ended up not only extremely successful, but also the baker general for the entire Continental Army. Niel also operates The Georgian Kitchen and is well-known for his impeccable attention to detail when he recreates historical recipes. Niel also teaches 18th century cooking at Historic Eastfield. For this talk, he baked not only give different gingerbreads, dating from the 1400s to the very late 19th century, he also baked stunning examples of molded gingerbreads. Although they were all delicious, my favorite was New York Gingerbread, and Niel was kind enough to share the recipes with everyone. So, when it came time to bake for a friend's housewarming gift (a very charming idea my husband came up with - salt, a broom, and bread), I immediately wanted to try my hand at the New York Gingerbread. Of course, I've recently been watching quite a bit of the Great British Baking Show, and this recipe felt a bit like one of their technical challenges - a classic, but with VERY sparse ingredients. The original recipe, which was published in the Dewey Cookbook in 1899, reads: 1 cup sugar 1 1/2 eggs 1 1/4 teaspoonfuls ginger 1/2 pint milk, half sweet, half sour 3/4 cup butter 1/4 teaspoonful salt 2 1/2 cups flour 1 teaspoonful soda Beat well together the sugar, butter, eggs, and salt. Add the balance of the ingredients and bake. New York Gingerbread (1899)I assembled my ingredients, but because who on earth knows how to add a half an egg, I doubled the recipe thusly AND added instructions, just for you lay-bakers. You'll also notice, that unlike typical gingerbread recipes, this one contains neither molasses nor spices other than ginger. It gives it a gentle heat and a nice purity of flavor. And despite 2 cups of sugar, it's not overly sweet. 2 cups sugar 1 1/2 cups butter (three sticks) 3 eggs 5 cups flour 1/2 teaspoon salt 2 1/2 teaspoons ground ginger 1 teaspoon baking soda 1 cup milk 1 cup buttermilk OR 1 tablespoon lemon juice topped off by milk to make 1 cup sour milk Preheat your oven to 350 F and lightly grease two standard loaf pans. Cream butter and sugar together until smooth, then beat in eggs. Add flour, salt, ginger, and baking soda and start to stir into the butter mixture. Then add the sweet milk and stir a little more, then the sour milk or buttermilk. Work quickly to stir everything together - the batter will be quite thick. Spoon into each loaf pan until the batter looks equal, then place in the hot oven and bake approximately 65 minutes or until the loaves are cooked through. Let cool in the pans for a few minutes, then tip out onto a cooling rack to finish cooling. Serve warm or room temperature plain or with with whipped cream. For a great deal of guesstimating, I think this turned out quite well! A couple of notes: one is that I didn't have enough white all-purpose flour to do the double bake, so I used about half spelt flour. Which likely accounts for the darker color than Niel's. In addition, my baking soda was over a year past its expiration date. Between the heavier flour and the slightly flat soda, I think that accounts for the denser texture than Niel's, which were quite fluffy, but still chewy. That being said, the flavor was almost identical, although you can taste the spelt flour a bit in mine. Final verdict? I would totally make this again. It's addictively subtle - just spicy and sweet enough that you want to keep eating it. The crust is a bit crunchy right now, which I like, but as it sits (I'm storing it in a gallon ziplock bag), the crust will get tender and a bit sticky. Much like banana bread, which this strongly resembles. Niel says he bakes this in loaf pans (like I did) and does two things: either he double bakes it to make rusks, or he makes a trifle with custard and (get this) LEMON CURD. He's such a genius, and I'm so grateful he shared this recipe! Also grateful I was able to make a pretty good version of my own. And, as always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. A while ago I made cherry bounce. It's a very old-fashioned drink that was apparently much-beloved by George Washington. I speculated about George and cherries even longer ago, in a post that remains today one of my top-viewed posts. You see, cherries are not even remotely in season in February, and George was a lover of walnuts. Although he preferred English walnuts, black walnuts were easier and cheaper to get. I live nearby where George was stationed during the end of the Revolutionary War. And there are black walnut trees a-plenty in my area. I've thought about harvesting them, but they're so fussy and difficult, and my days so busy, that I've never bothered. I leave them to the squirrels, who seem to cleverly leave them in our driveway so our cars will crack them for them. They then carry them to a shallow stone in our lawn to finish cracking them open. This President's Day weekend I worked on the Saturday, went to a friend's birthday party (she got her own quart of bounce and a pair of tiny brandy glasses for a present), had errands to run on Sunday, and worked on the holiday Monday. So it was just the other day that I got to enjoy a small (and very 18th century looking) glass of the cherry bounce. I even lit a candle for George, Abe, and all my other favorite presidents (including Teddy Roosevelt, of course). My husband thinks it tastes like cherry cough medicine, and I'll admit the brandy is a bit strong. Gives you a lovely warm feeling if you're cold, that's for sure. But you do get just a slight sweetness (I used much less sugar than the historic recipe) and a nice bright sour cherry taste. The color is also absolutely beautiful and comes just from the fruit - no artificial colors here! Next time, I think I'll pack the jar right full of sour cherries for a stronger cherry taste. And maybe spend just a smidge more money on the brandy. :D Cheers, all. If you liked this recipe and want to see more, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian or supporting us on Patreon. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed