|

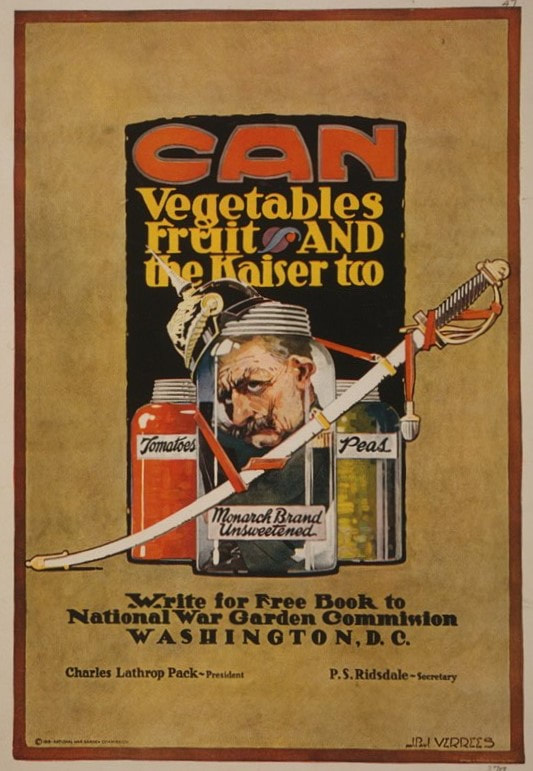

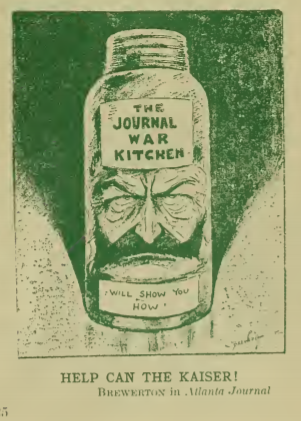

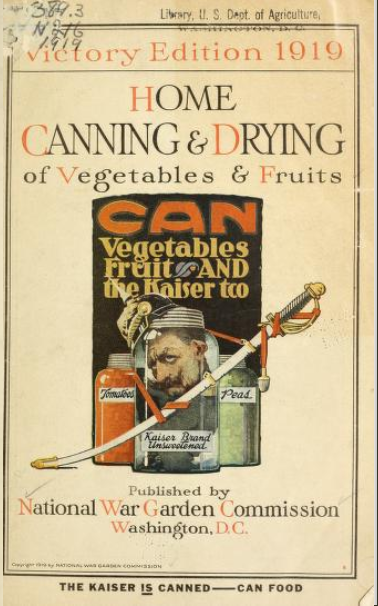

"Can Vegetables, Fruit, and the Kaiser, Too. Write for Free Book to National War Garden Commission, Washington, D.C." September is still preserving time, so I thought the next few World War Wednesdays would be about canning. This is another of my favorite World War I propaganda posters. Developed by the National War Garden Commission, the poster shows glass jars with zinc tops. Tomatoes at left, peas at right, and front and center, the profile of Kaiser Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia. His spiky German helmet and saber hang on the jar, which is labeled "Monarch Brand, Unsweetened." Eminently clever, the poster implies that home preserving has the power to defeat the might of the German Empire and the Kaiser himself. The First World War was one of the first times that ordinary Americans were called upon to preserve food in their homes. Many Americans, especially those in rural areas, were already canning and preserving the bounties of their home gardens. But as commercial canning became increasingly widespread, inexpensive, and safer, people with easy access to food retailers found it much easier to simply purchase canned goods, instead of going through the bother of putting up their own. Many people were still using the tried-and-true, but not necessarily safe, methods of their forebears. And while water bath canning was increasingly outpacing the traditional food preservation methods of fermentation, drying, and sealing jam with paraffin wax, water bath canning low acid vegetables still was not 100% safe. But as the government encouraged food conservation and food preservation, the National War Garden Commission stepped up to the plate. Founded (and funded) by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, the National War Garden Commission published a series of food preservation pamphlets that were used all over the country by home economists and women's groups to encourage home canning. The National War Garden Commission was also behind the school garden movement, but that's another post. The Commission would go on to produce a number of pamphlets on war gardening (renamed "Victory Gardening" post-war, a term that would be revived during the Second World War), including one pamphlet entitled "The War Garden Guyed," published in 1918. A clever play on words ("to guy" someone was to make fun of them, or ridicule), the "Guyed" contained cartoons, poems, and slogans both promoting and making fun of the gardening and food conservation movements. Submitted by newspaper editors, soldiers in the trenches, magazines, and ordinary people, the collection is quite a fun read, and not the only version the National War Garden created. "Raking the Gardener and Canning the Canner" predated "The War Garden Guyed" by one year - published in 1917, a quick turnaround indeed and indicates how quickly ordinary people adjusted to the idea of home gardening and canning. You can view almost all of the National War Garden Commission pamphlets on archive.org. In 1919, the National War Garden Commission used the "Can the Kaiser" poster image again, this time on their revamped "Home Canning & Drying of Vegetables and Fruits," rebranded "Victory Edition" post-war. At the bottom of the cover, it reads, "The Kaiser IS Canned." Although the fervor for home canning, thrift, and self-sufficiency continued into 1919 and 1920, by the time economic prosperity had returned full-force to give us the Roaring Twenties, most ordinary people who took up canning for the war effort abandoned it in victory. But I like to think that many of the food preservation lessons learned during the First World War would be revived and put to good use by the time the Second World War rolled around. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more!

1 Comment

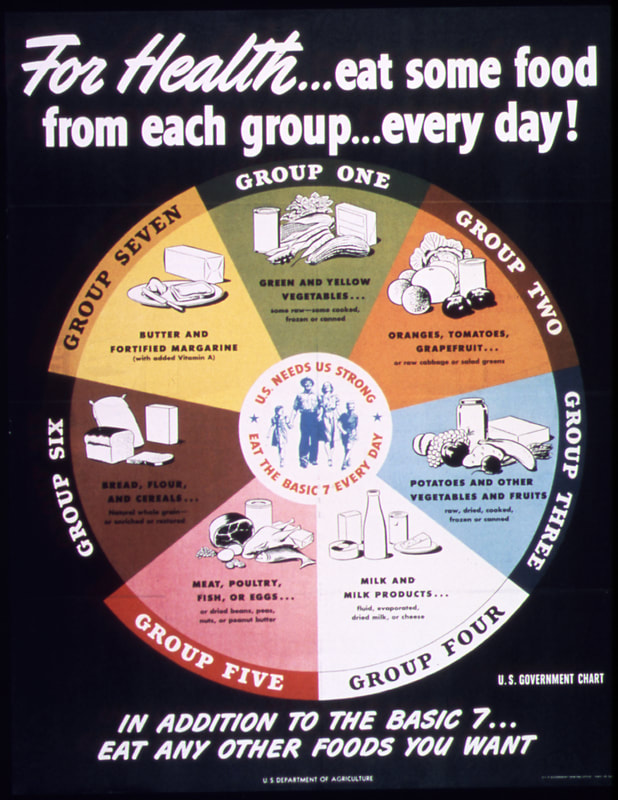

During the Second World War, new research into nutrition science and the importance of vitamins meant that scientists and government officials alike were looking to increase public awareness about these new discoveries. In particular, emphasis was placed on the importance of keeping the populace healthy, strong, and able to keep up the punishing pace of total war. The Basic 7 was a precursor to the food pyramid and "MyPlate" interpretations of an easy way for Americans to know what healthful foods to eat. In effect from 1943 to 1956, the Basic 7 were replaced with a consolidated Basic 4, and later the food pyramid. Group One: Green and Yellow Vegetables Designed to encourage Vitamin A intake, this group emphasized dark leafy greens and other green and yellow vegetables. These vegetables were recommended to be eaten raw, canned, cooked, or frozen. Although I'm guessing you were supposed to heat the frozen ones first. Night blindness and poor eyesight was a real fear for both soldiers and industrial workers alike and Vitamin A was touted as a preventative against poor eye health. Group Two: Oranges, Tomatoes, Grapefruit This group also included raw cabbage and salad greens, both good sources of Vitamin C, along with oranges, tomatoes, and grapefruit. Vitamin C deficiency was by the 1940s long known as the cause of scurvy. Canned tomatoes and oranges in particular were popular sources, but as this group points out, other foods like raw cabbage and salad greens, especially spinach, also have very high levels of Vitamin C. Group Three: Potatoes and Other Vegetables and Fruits This group was meant largely to round out the vegetables with fiber and carbohydrates. If you haven't noticed by now, the first three groups are all made of fruits and vegetables, as they were plentiful and not rationed during the war. Potatoes in particular were touted during both World Wars as an alternative to bread. Group Four: Milk and Milk Products Long considered the "perfect food," - a balance of fats, protein, and sugars, by the 1940s milk and other dairy products were also recognized as excellent sources of calcium. With the exception of cheese, most dairy products were not rationed during the war and cottage cheese in particular was promoted as a high-protein meat substitute. Group Five: Meat, Poultry, Fish, or Eggs This group also included dried beans, peas, nuts, and peanut butter, and emphasized protein. Meat was quite heavily rationed during the war, so fish, beans, and nuts were often suggested as meat substitutes. Soybeans (called "soya" in the period) were a "new" miracle protein source that never really caught on. At least, not until West Coast hippies were introduced to tofu by Japanese Americans in the 1960s. Group Six: Bread, Flour, and Cereals In the 1940s bread and other cereal products were still the backbone of many American meals. Cold or hot cereal, toast, or pancakes for breakfast, sandwiches for lunch, bread with every dinner - these were the typical meals of most Americans. But while the simple carbohydrates of refined white bread were vaunted before the First World War, by the Second World War nutritionists realized that white flour had been stripped of most of its nutrition with the elimination of the wheat germ. So whole grains, flour, and cereal products were touted for their nutritive value. But, because white flour was so very popular, "enriched" or "restored" cereal products were also allowed. This gave rise to foods like Wonder Bread - so-called because it was "enriched" with a half a dozen vitamins and minerals - something allowed thanks to technological advances in artificial vitamin production. Group Seven: Butter and Fortified Margarine Yes, you read that correctly. Butter was it's own food group during WWII. Seems crazy these days, but this group was also focused on getting Americans adequate supplies of Vitamin A. Today, the Vitamin A found in animal-based foods is called Vitamin A1, or retinol. Vitamin A deficiency includes dry eyes and eventual blindness. So it was an important vitamin to keep people in top working condition. Ironically, a tablespoon of butter only gives you about 11% of your daily recommended intake of Vitamin A, whereas other common WWII ration-relievers like beef liver and the oft-dreaded cod liver oil, provide more than enough Vitamin A per serving. But perhaps because rationing limited fats, officials felt that by putting butter on the Basic 7, they would be relieving some of the monotony of rationed diets. In addition, the more detailed poster below, indicates that eating butter or margarine helps you feel more satisfied or fuller after a meal. Conventional wisdom that has stood the test of time, as fat helps you feel more satiated than just about any other food. By equating butter with fortified margarine, officials also helped remove some of the stigma from margarine, which still held some stigma as poverty food with a whiff of slaughterhouse about it, as originally margarine was made from scrap meat fats, as opposed to the supposedly more wholesome vegetable oils that were common by the 1940s. Of course, we know now that the hydrogenating process to solidify vegetable oils creates trans fats, one of the most harmful fats you can eat. But, like the effects of the atomic bomb, no one really knew that in the 1940s. Altogether, the Basic 7 emphasized nutrients, rather than calories, as later version would come to embrace. The Basic 7 focused on bodily performance, rather than weight loss. "Eat a Lunch That Packs a Punch!" was a common motto from the war and was designed to keep up health, strength, and stamina during mobilization. All images in this blog post are from the National Archives and Records Administration.

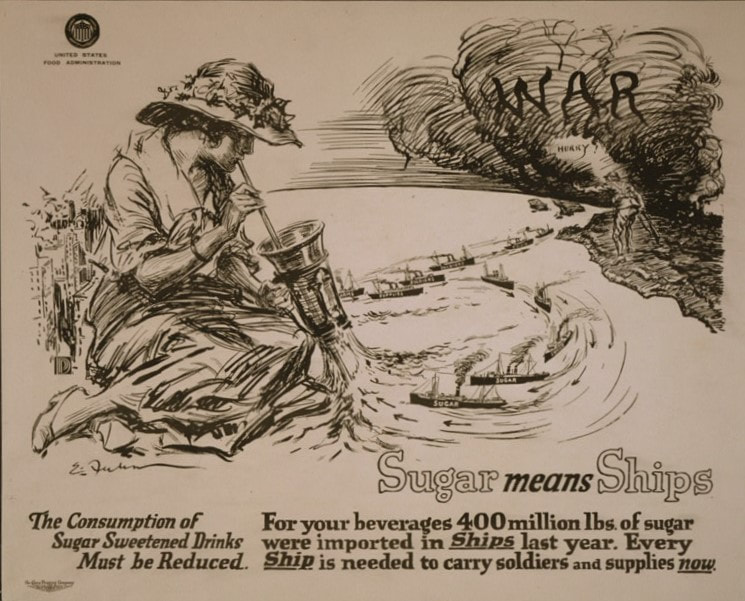

If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! "Sugar means Ships. Consumption of Sugar Sweetened Drinks Must be Reduced. For your beverages 400 million lbs. of sugar were imported in Ships last year. Every Ship is needed to carry soldiers and supplies now."

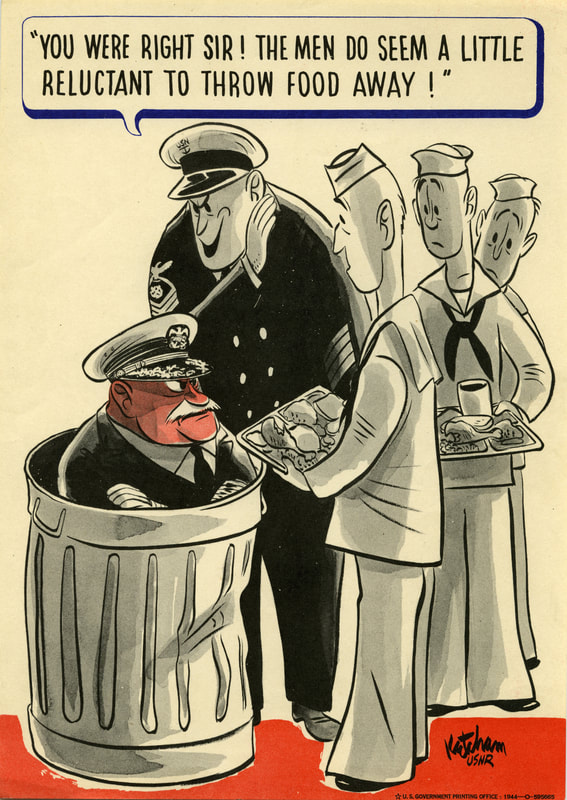

This unobtrusive but nonetheless striking propaganda poster from the First World War was produced by artist Ernest Fuhr in 1917 for the United States Food Administration. In it, a soldier stands on the shores of Europe, rifle in hand, beckoning and shouting "Hurry!" to steamships carrying supplies from the United States as he heads toward the dark clouds of War. At left, in the foreground, a fashionable young woman drinks from a giant soda fountain cup. By sucking on the straw, she diverts more than half of the steamships, these labeled "sugar," back to the United States and into her cup. Although sugar was not rationed for civilians until the fall of 1918, a number of factors are at play here. First, is that unlike during World War II, the United States had poor mobilization of industry. In the short year and a half that the United States was in the war, not a single merchant ship was completed in time for war service, though 122 were started and completed after the war. In addition, even when the United States was a neutral country, German U Boats were always a risk (see: the sinking of the Lusitania). When it came time to ship millions of troops and supplies overseas, every ship possible was pressed into service. At this time, although the United States did produce its own sugar, largely through sugar cane plantations in Louisiana, it also purchased a great deal of sugar from the Caribbean, particularly Cuba. With railroads also tied up as goods and people moved east, ships were among the most efficient ways to ship shelf-stable staples like sugar. Leading up the U.S. entrance into the First World War, the United States had the highest per-capita sugar consumption in the world, consuming 85 pounds of sugar per person annually, compared to just 40 pounds in England. This extremely high sugar consumption was tied in part to the Temperance movement. Under the conventional wisdom of white, middle- and upper-class Protestants, alcohol was a social evil, and the basement saloons and bars that dotted urban neighborhoods throughout the country, with their free lunches to entice customers inside to drink more beer and other liquor, were dens of iniquity, tempting working class men to drink up their wages, to the detriment of their families. Nevermind that for many immigrant communities, social drinking was a convivial community event that often involved women and children (the Yankee reformers would be horrified). Soda fountains and tea rooms were a growing alternative. Soda fountains in particular were attractive to young people. And the reputation of fizzy "mineral" waters and "tonics" like Coca-Cola (which contained cola leaves - the main ingredient in cocaine) gave a veneer of health to what was otherwise sugar water. Ice cream was another extremely popular dessert turned snack in the Progressive Era and commercial production skyrocketed in the years leading up to the war. Tea rooms served fancy iced tea cakes and cookies, sweetened tea, and "dainties" like creamy fruit salads made with Jell-O - and plenty of sugar. The conventional nutrition wisdom of the time was that sugar was a carbohydrate, and carbohydrates gave you energy, therefore, sugar was good for you. Although sugar was not rationed for civilians during the war, it was for commercial enterprises. The production of ice cream and soda were both restricted during the war starting in the fall of 1917, and restaurants, hotels, and railroad dining cars were banned from leaving sugar bowls on the tables, as had previously been the norm. Civilians were encouraged to give up their sugar addictions, or at least transfer them to other sweeteners like honey, corn syrup, molasses, and maple syrup. Recipes for cakes, cookies, and preserving with these sugar alternatives were released to the public as part of the war effort. Although it's not clear if these efforts did have an effect on American sugar consumption during the war, the popularity of soda fountains, ice cream, gelatin fruit salads, and candies continued to be an American obsession. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! During the Second World War, Americans were under mandatory rationing to free up food supply for the American military and Allied nations. But for the men and women abroad, particularly aboard Naval ships where the war came and went as ships stalked each other across oceans, food was plentiful. Naval ships in particular were famous for carrying ice cream on board at all times. For many enlisted men, life in the military provided some of the best meals of their young lives. The draft had revealed just how deep the deprivations of the Great Depression went. 45% of American men were deemed unfit for military service in 1942. Standards had increased, but bad teeth, poor eyesight, and other defects were blamed at least in part on malnutrition. Faced with abundant, well-prepared food, many young people went whole hog in the mess hall. But military brass were keenly aware of the sacrifices being made at home, and did their best to prevent food waste. The Navy produced a series of propaganda posters discouraging food waste. The above poster is among my favorite. In it, a red-faced, mustachioed Naval Captain sits in a dented trash can, arms crossed, glowering. The Chief Petty Officer says, "You were right, Sir! The men do seem a little reluctant to throw food away!" While worried-looking sailors with full mess trays (including chicken legs with just a bite or two out of them) hover by the trash, unsure how to proceed. The message was clear - troops were not to waste what ordinary Americans had sacrificed to provide for them. For more from the National Museum of Health BUMED collection, all by the same artist in the same engaging style, see the gallery below. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed