|

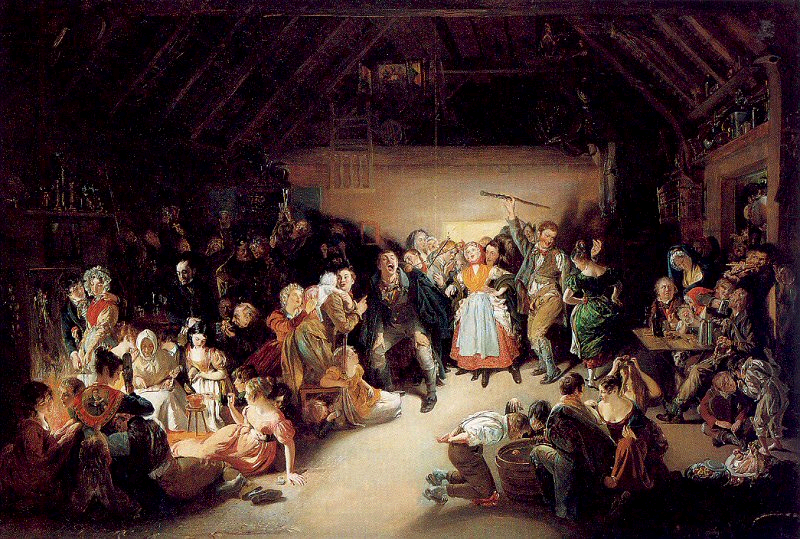

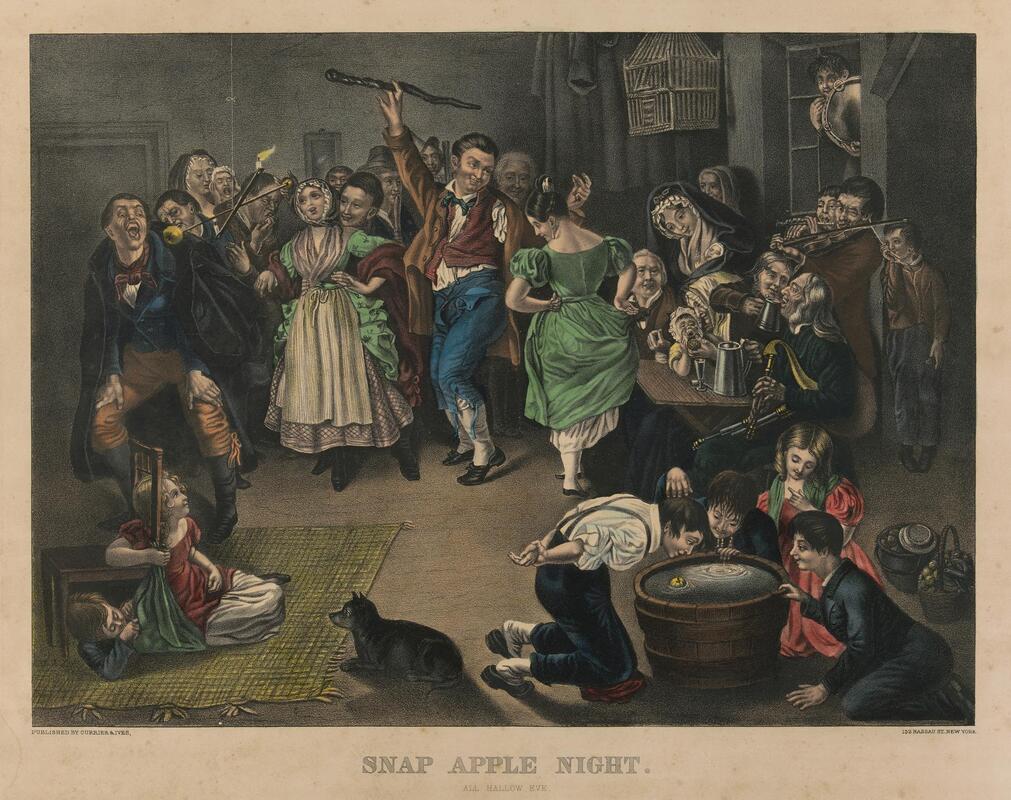

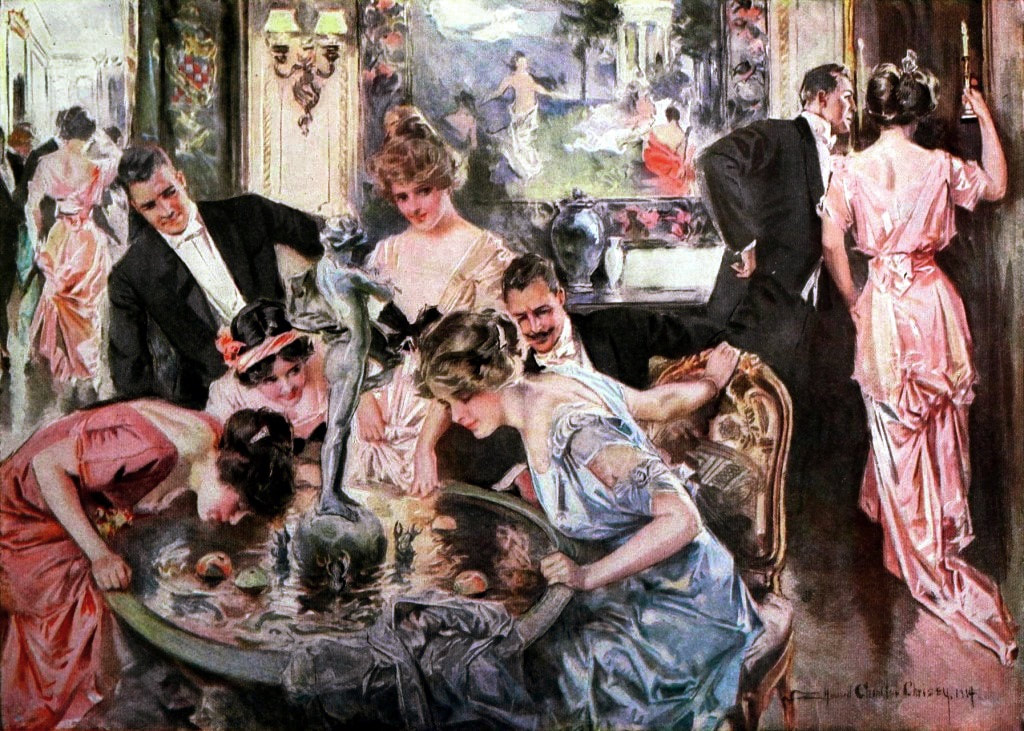

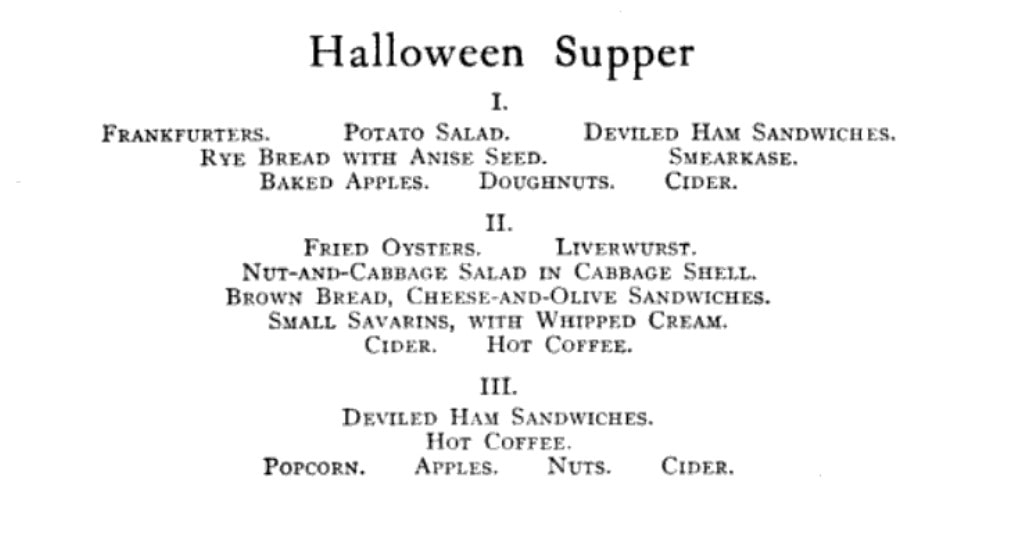

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Happy Halloween, everyone! When it comes to Halloween, pumpkins get all the love. But Halloween's REAL favorite fruit is apples. Let me explain. The origins of Halloween date back to ancient Ireland and Scotland - a place where the now-ubiquitous pumpkin was not available until the 16th century at the earliest, and not really in practice until the 19th century. But apples? Apples were everywhere. They were the best fruit for storing over the long winters. Certain varieties kept better than others, but unlike soft berries or less sweet root vegetables, apples were a reliable source of sugar at a time when calories were all-important. 19th and early 20th century historians often attributed the apple celebrations of the British Isles to Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit orchards, including apples, which in Romance languages share the Latin root word "pomum," meaning fruit. "Apple" was also originally meant to describe all kinds of fruits, not just the Malus domestica, much like "corn" historically referred to all types of grain (and which is why most of the rest of the world refers to it as "maize.") I'm skeptical of the direct connection to Pomona. More likely was simply the fact that apples were in season at this time of year. Apple harvest generally lasts from August through the end of October, depending on the breadth of your apple varieties. Apples were eaten fresh, put up as sauce or apple butter, dried, and processed into apple cider, hard cider, scrumpy, applejack, and apple cider vinegar. But for Halloween, fresh apples were still very common, and a LOT of Halloween traditions involve fresh apples. Snap Apple NightIn Ireland, Halloween was often referred to as "Snap Apple Night," as is illustrated by the classic painting above by Irish artist Daniel Maclise. Maclise based it on a real Halloween party he visited in Ireland in 1832. He illustrates many of the classic traditions. At left, a courting couple burns nuts on the hearth grate to see how their relationship will fare and girls drip molten lead into water to read their fates in the shapes. At right, boys bob for apples and others play pranks on the musicians. And the center, namesake of the painting, is snap apple - a rather precarious and hilarious game. A pair of wooden sticks are fastened together into a cross. On two opposing ends, the sticks were sharpened and apples stuck on. On the opposite ends, burning candles were affixed. The whole thing was hung from the ceiling on a string, and set spinning. The goal was to catch and remove the apple using only your mouth - no hands allowed - without getting hit in the face by a burning candle, or the hot wax. Upon exhibition, Maclise's painting was accompanied by the following poem: There Peggy was dancing with Dan While Maureen the lead was melting, To prove how their fortunes ran With the Cards could Nancy dealt in; There was Kate, and her sweet-heart Will, In nuts their true-love burning, And poor Norah, though smiling still She'd missed the snap-apple turning. As Irish immigrants came to the United States following the great potato famine of the 1840s, they brought their Halloween traditions with them. This rather poorly rendered lithograph by Currier & Ives is a copy of a copy of Daniel Maclise's original painting. Printed in 1853, it reflected the adoption of Halloween by Americans. Missing the divination happening hearthside, this lithograph focuses on the game of snap apple, the dancing and music, and in the foreground, bobbing for apples. This image from the frontispiece of The Book of Hallowe'en, published in 1919 by Ruth E. Kelley, shows the staying power of Maclise's painting, and the power of the mysterious history of Halloween. In this illustration, ("from an Old English print"), we have bobbing for apples and a well-lit game of snap apple. The clothing of the people in the illustration evokes somewhere between the turn of the 19th century and the 1840s - the fuzziness of the time period part of the mystique of the book, which purports to trace the history of Halloween and yes, does link it to the Roman festivals for Pomona. Kelley's book was part of a resurgence of interest in Halloween throughout the United states, and one of a number of books published on the subject, including more serious histories like hers, and more commercial publications like Dennison's Bogie Books. Snap apple remained a popular game, although later versions were slightly safer. As the century wore on and we turned to the 20th century, alternatives went from attaching the apples with strings, to replacing the candles with small sacks of flour (far less dangerous than flame and hot wax, but no less humiliating to get hit in the face with a puff of flour), and eventually simply hanging apples from a string. An even easier later variation even replaced the apples with donuts! As Halloween traditions shifted from at home parties to public events like costume parades and community trick or treating, snap apple faded into obscurity. History of Bobbing for ApplesThe above painting is one of my favorites from the time period. Howard Christy's "Halloween" depicts a very fancy Progressive Era Halloween party that still smacks of the Gilded Age. The decadent mansion, with enormous Classical paintings, gilded furniture, and elaborate gaslights is filled with men in tuxedoes and sleek haircuts and women in glistening silks and satins - nary a fancy dress costume in sight. In the foreground a fancy Classical style fountain has a few apples floating in it, and one young lady bends close - contemplating bobbing, perchance? - while others look on. In the background, a young woman and a man gaze into a mirror - the woman holds a lit taper candle, which evokes the Halloween divination tradition of gazing into a dark mirror by candlelight at midnight. Supposedly your future husband would appear. It's a slightly ridiculous take on the historically very messy and hilarious tradition of bobbing for apples. Like snap apple, bobbing for apples (sometimes known as dunking or ducking for apples), was a game of hilarity, skill, and danger. A large basin - often the wooden laundry basin - was filled with water and apples floated on top. The object of the game was to retrieve them with only your mouth - hands behind your back. There were a number of tricks to retrieve them. Some tried to grab the stem in their teeth. Others used their lips to suction the side of the apple. Still others shoved their entire heads under water, trying to trap the apple between their mouth and the bottom of the basin. Like with snap apple, courting couples could cooperate to sandwich an apple between them. And like snap apple, bobbing for apples drifted into obscurity as the 20th century wore on, although it remained more firmly in the American cultural consciousness than snap apple.  This undated postcard, likely from the turn of the 20th century, features two girls and a boy bobbing for apples. It's one of the few images of the period showing a girl actually doing the bobbing while the other two watch. A smoking jack o'lantern typical of the period sits in the foreground. Toronto Public Library collection. Apple Divination In this 1909 Halloween postcard by illustrator Bernhardt Wall, a young woman is tossing a long apple peel over her shoulder, believing that the peel will fall to the floor in the shape of a letter that will reveal the first letter of her future husband's name. Posted by collector Alan Mays to Flickr. Like May Day and Midsummer, Halloween was chock full of divination opportunities, and apples were at the center of several. The more famous is apple peel divination. A young girl would peel an apple in a long strand - sources vary over whether she had to do the whole apple in one unbroken peel - and toss the peel over her shoulder. Supposedly, the peel would land in the shape of the initial of the man she was to marry. In practice it seems like there would be a lot of S's, C's, L's, and O's, and not too many T's or H's. Another romantic divination game involved the apple seeds. Pressing fresh seeds to your forehead you would assign to each one a crush or romantic interest. The one that stayed on the longest was destined to be yours. Still other apple seed games involved squeezing them in your fingers. The direction they shot out of your fingers was where your true love would approach from. Candy and Caramel Apple HistoryAlthough apples were consumed regularly in the autumn months in northern climes all over the world, it wasn't until the late 19th century that the modern apple as we know it today developed. Starting post-Civil War, fruit orchardists like the Stark Brothers and agricultural college experimental stations began developing specific varieties of fruit, grafted for taste, disease resistance, ripening time, etc. With these scientific developments came the emergence of the modern dessert apple. Designed for eating, rather than for producing cider, these apples were sweeter than their predecessors. Apples, through improvements in orchard husbandry, were also getting larger, more standardized, and shipped better. People in cities were able to access fresh apples on an increasing basis. Which led to innovations in eating. Candying fruits in sugar or honey syrup is ancient. But the idea of dipping fresh apples in a candy coating was relatively new. Candy apples are coated in a shiny red candy glaze, whereas caramel apples are dipped in sticky brown caramel. Taffy apples are somewhere in between. Toffee apples, as they are called in England, are similar to both. Although candy apples are widely attributed to William Kolb of New Jersey in 1908, but toffee apples and caramel apples have newspaper references in England and France in the 1890s. Also in 1908, one newspaper article for "Caramel Apples" went viral - appearing in 62 newspapers across the country. It is not quite the same as the caramel apples we associate with today, which are more similar to British toffee apples of a sour apple dipped in soft caramel. These were more like a combination of the medieval candied apples and modern caramel apples, with nary a stick in sight. Here's the article in its entirety: CARAMEL APPLES ARE GOOD. As you can see from the recipe, these apples must have been incredibly sweet as they were both cooked in syrup and then also covered in caramel and more syrup and served with whipped cream. No wonder the sugar addicts of 1908 made this recipe go viral! Caramel and candy apple associations with Halloween come a bit later, coinciding with the apple harvest season. Most Americans connect them to county fairs and old-fashioned trick-or-treating, when people still made homemade treats to distribute before the candy scares of the 1970s. Today, they're found everywhere from pick-your-own apple orchards to places like Coldstone Creamery, although most are now dipped in chocolate, rather than caramel or candy, as getting a candied coating that is thick enough to stick and soft enough not to break your teeth is a bit of a lost art. Chocolate is far easier to handle. Apple Cider For Halloween MenusAlthough the Pumpkin Spice latte may have taken over fall in today's world, in my opinion apple cider is a much better companion. And historic cooks and party planners agreed. Apple cider was often featured in Halloween menus like the ones above from the late Victorian period on. This would have been sweet cider, of course, because even before Prohibition most home economists and domestic scientists were advocates of the Temperance movement. Whether served cold or spiced, cider was often associated with other more casual foods like doughnuts, popcorn, frankfurters (aka hotdogs), pickles, and nuts. Outdoor events like bonfires, hay rides, and outdoor parties along with public events where children or teenagers were present were also commonly associated with simpler foods like outlined in the menus above. The prevalence of cider reveals its more industrial origins. Apple orchards growing dessert apples were more prevalent, as older heirloom cider apples fell out of use. Commercial bottling in the mid-19th century allowed companies like Martinelli's to produce hard cider and sodas. The growing popularity of the Temperance movement shifted companies away from hard cider and toward unfermented sweet cider, which remains the focus of Martinelli's today. Companies like Mott's also started out making hard cider, and then shifted to sweet in the 20th century as bottling sanitation improved and the demand for non-alcoholic beverages increased. Today, most commercially-sold apple juice is filtered and pasteurized, making for a thinner-bodied, sweeter, and less acidic product. Apple cider is generally not filtered and is sometimes sold unpasteurized, as the acidity level gives it anti-microbial properties. This, along with the sugar content, is generally also what allows apple cider to ferment, rather than spoil. Today, most hard cider is inoculated with champagne yeast, but historically wild yeast would naturally gather in the sugary liquid. Sweet cider is available most places where apples are grown, and New York is the second-largest apple-producing state in the country, so I'm lucky to have ample access to it. I've even made my own with a historic cider press! (Just a small, household sized one, not one of the giant presses.) In all, apples take the cake (sometimes literally) in Halloween eats in large part because they were a readily available source of sugar a time when refined cane sugar was largely the purview of the wealthy. And besides which, although pumpkin pie was also associated with Halloween, there's only so much of it you can eat before you get sick of it. Apples - whether candied and carameled or turned into pie, salads, cakes, muffins, crisps, dumplings, sauce, butter, cider, or even candy - are tough to get sick of, especially after a long, hot summer. What do you thing - do apples beat out pumpkins for ideal Halloween eats? Or should we be celebrating other fruits altogether, like pears or blackberries? Edwardian HalloweenAs I was working on this post, I was watching BBC's Edwardian Farm (which is also available on Amazon Prime - using the link helps support The Food Historian). Episode 2 is great to watch in its entirety (lime burning, apple cider pressing, and egg preservation, oh my!), but I've started the YouTube video below at the beginning of the Halloween party, where you'll see a variation of snap apple, an apple divination game involving sticking apple seeds to your forehead, and of course, fermented apple cider. Enjoy, and have a happy, apple-ish Halloween! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

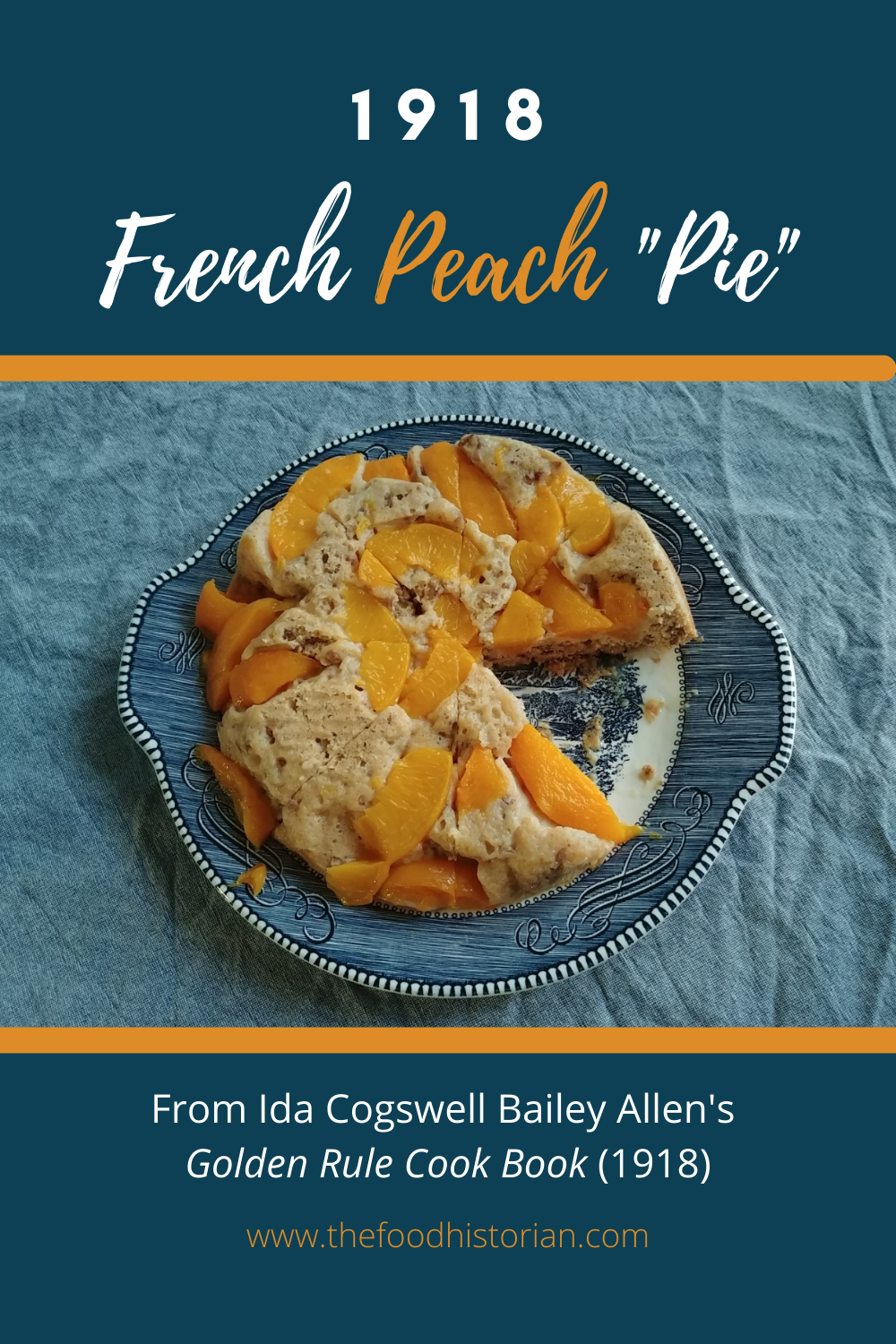

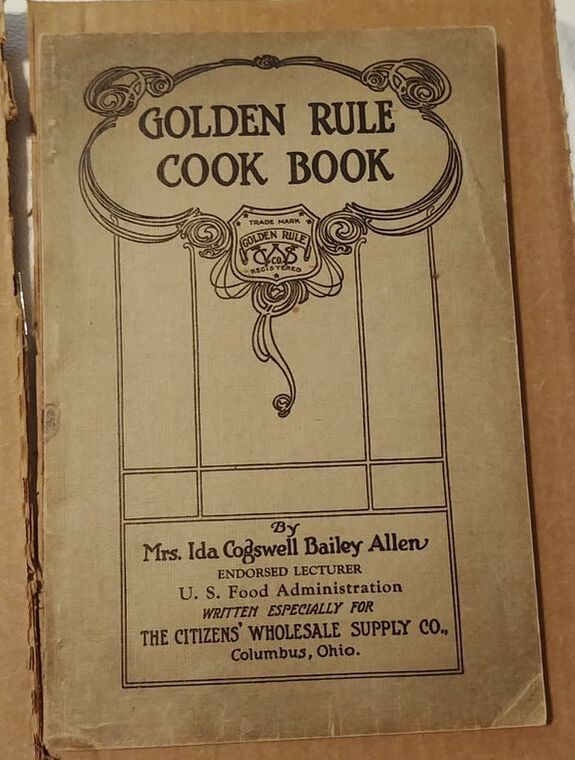

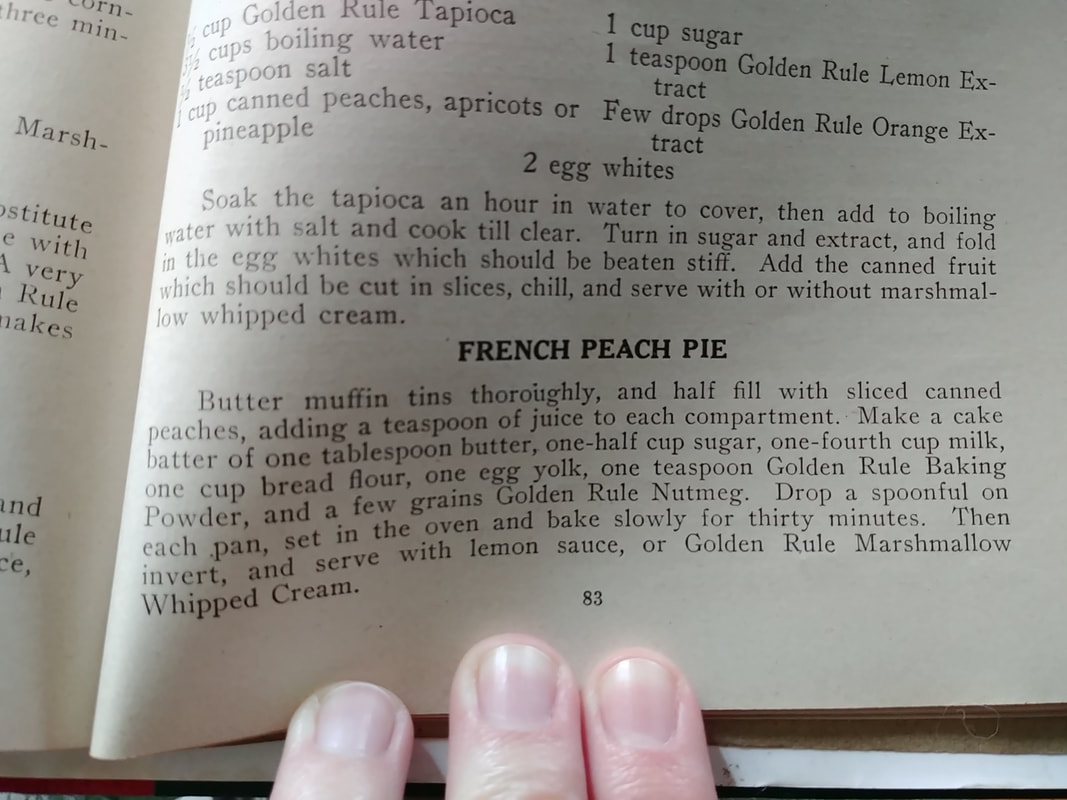

As you may know, I am a huge fan of Ida Cogswell Bailey Allen. A PROLIFIC cookbook author with over fifty titles to her name, I'm not sure anyone has ever done a comprehensive bibliography of her work. So when I saw this little cookbook on Etsy, I squealed. I squealed in part because, as far as I can tell, this is one of her first cookbooks! And I also got excited because she is listed as an "endorsed lecturer" for the United States Food Administration! The cookbook does have a few ration-friendly recipes in the very back - basically for wheatless baking recipes. But the majority are regular ol' recipes designed for The Citizens' Wholesale Supply Company from Columbus, Ohio. There's not a lot out there on this company, but from what I can tell it started out as a co-op, and then morphed into a company focused on food products - the Golden Rule brand. The Golden Rule Cook Book, (not to be confused with THIS Golden Rule Cook Book of meatless and vegetarian recipes), doesn't appear to be digitized anywhere, nor are there many versions for sale online. Which makes it all the more interesting! It was likely designed as an advertising cookbooklet, which were a common advertising device for food products and companies from the 1890s until quite recently. As you can see, the recipes all call for at least one Golden Rule brand ingredient, often a flavoring extract. This "French Peach Pie," however, caught my eye. It appeared to be an upside down cake, albeit baked in muffin tins. Ida Bailey Allen probably called it "French" because it loosely resembles tarte tatin. I wasn't sure exactly how many muffin tins, as I knew some historic tins were only 6 muffins big, and I had only a 1 dozen pan. So I decided to make a few changes. First, I made it in a round cake pan, instead of individual cakes in a muffin tin. I also added chopped pecans, because I had some and that sounded good with peaches. I added a pinch of salt, because Ida never does and baked goods taste flat without it. More commentary with the recipe. French Peach "Pie"I put the "pie" in quotes because this is really an upside down cake. If I make this again, and I think I will, I am going to make a few more changes, mainly using regular all-purpose flour and using the full egg, instead of just the yolk, as the batter was a bit dry and needed an infusion of extra milk. I even added a little of the leftover peach juice! Here's the verbatim recipe: Butter muffin tins thoroughly, and half fill with sliced canned peaches, adding a teaspoon of juice to each compartment. Make a cake batter of one tablespoon butter, one-half cup sugar, one-fourth cup milk, one cup bread flour, one egg yolk, one teaspoon Golden Rule Baking Powder, and a few grains Golden Rule Nutmeg. Drop a spoonful on each pan, set in the oven, and bake slowly for thirty minutes. Then invert, and serve with lemon sauce, or Golden Rule Marshmallow Whipped Cream. Here's my translation: 1 quart canned peaches 1 tablespoon butter, softened 1/2 cup sugar 1 egg yolk 1/4 to 1/2 cup milk Leftover peach juice 1 cup bread flour 1 teaspoon baking powder pinch of salt (1/4 teaspoon at least) 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon 1/4 cup chopped pecans (optional) Well-butter a 9 inch round cake pan. Add the peach slices to the bottom of the pan (I was missing a few from my quart from an earlier snack), and a few tablespoons of the juice. In a large bowl, cream the butter and sugar (it WILL work, just takes a minute), then mix in the egg yolk. At this point I dithered between adding the milk or adding the flour, or alternating. I ended up adding the milk and blending well before adding the flour, baking powder, cinnamon, and chopped pecans. This was VERY thick and did not even absorb all the flour, so I added another a little more milk and the remaining peach juice (about 1/4 cup) to make something more closely resembling a thick batter. I dolloped spoonfuls into the pan and tried to spread it out as best I could. I then baked it at 350 F (a "slow" oven is usually between 300 and 350 F), and 30 minutes wasn't quite long enough, as it was a larger pan, so I baked it for probably 40ish minutes, or until the cake was starting to turn golden brown at the edges. I then used a knife to loosen the edges of the cake, placed a cake plate on top of the pan, and flipped to release. Only a little of the cake stuck to the bottom - likely because I added a smidge too much milk. The cake was oddly firm-textured, I think because of the use of bread flour, and a bit dense. Next time I make it I am definitely using all-purpose flour and a whole egg and we'll see how that turns out. And I'll add a little more salt next time. And more peaches! There were insufficient peaches. Lol. And I think this recipe would be much better with fresh peaches, but canned were perfectly fine. The Golden Rule Marshmallow Whipped Cream I did not try, but it is simply whipped cream stabilized with a tablespoon or so of marshmallow creme. Liquid cream is much better, in my opinion! Especially since this cake was quite sweet. Interestingly, although this dessert is not in the World War I section of wheat-saving recipes, it calls for just one tablespoon of butter and one egg yolk, at a time when butter was rationed and eggs were often scarce. It would also be easy to shift this recipe to all barley flour or all or part rye flour to substitute for the wheat. The sugar could also probably be substituted in part or all for honey or maple syrup, which would give added moisture to the batter as well. What do you think? Would you try French Peach "Pie?" Maybe next time I'll be brave enough to try it in the muffin tin! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Thanks to everyone who joined me for Food History Happy Hour tonight! We talked about the history of diets, dieting, and diet culture, with forays into 19th century religious diets (including Sylvester Graham, Ellen H. White, and John Harvey Kellogg), raw food diets, veganism, changes in fashion influencing ideas about body types, the role of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and WWI in informing modern ideas about dieting, willpower, and health, the invention of the calorie, the development of dieting and diet fads in the 1930s and '40s, including juicing and the Hollywood diet, we talked about Dr. Norman W. Walker, Gaylord Hauser, Dr. Weston Price, Adele Davis, the role of animal fats in heart disease research, the history of artificial sweeteners, environmental factors in fatness and obesity, and that diet culture is super toxic! I probably could have talked for another hour on this subject, so we can revisit it, if you want to! Let me know in the comments.

We also made a (red) wine spritzer (I thought it was a bottle of white wine, it wasn't) and the history of wine spritzers. Wine Spritzer (19th century)

White wine spritzers are the classically low-calorie bar favorite in the late 20th century United States, but they date back to the early 19th century and are likely associated with the health and spa culture surrounding sparkling mineral waters, but may have also been simply an attempt to make an artificially sparkling wine!

Take your favorite wine - red or white - chilled, and cold club soda or seltzer or sparkling mineral water, also chilled. You can combine them in any ratio, but I think half and half is probably best. Further Reading:

Obviously, I had a blast doing this episode and I think I need to now do some biography blog posts about fad diets and nutritionism and their proponents. Did you know Gaylord Hauser had a TV show? You can alsowatch an interview with Adelle Davis!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

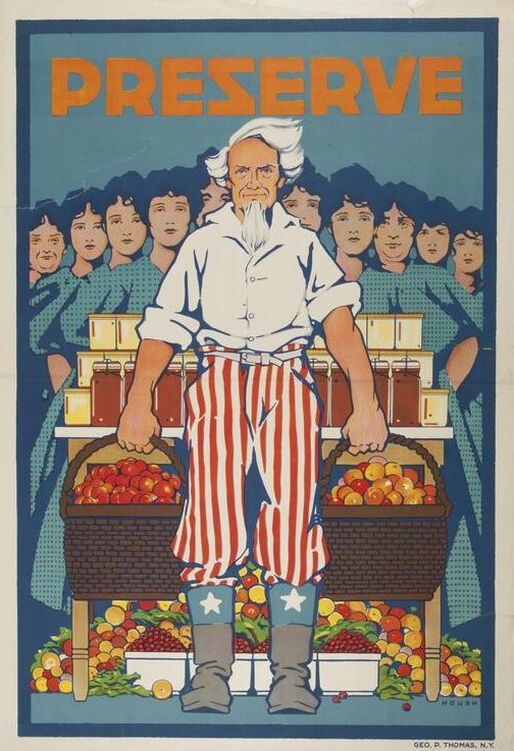

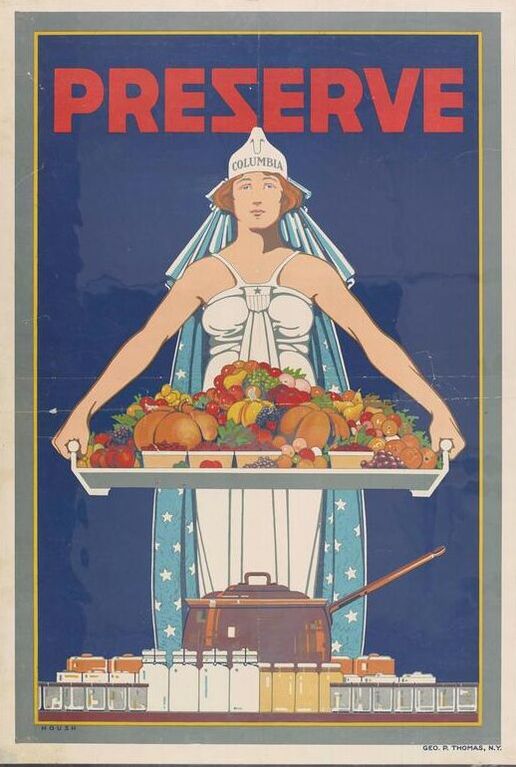

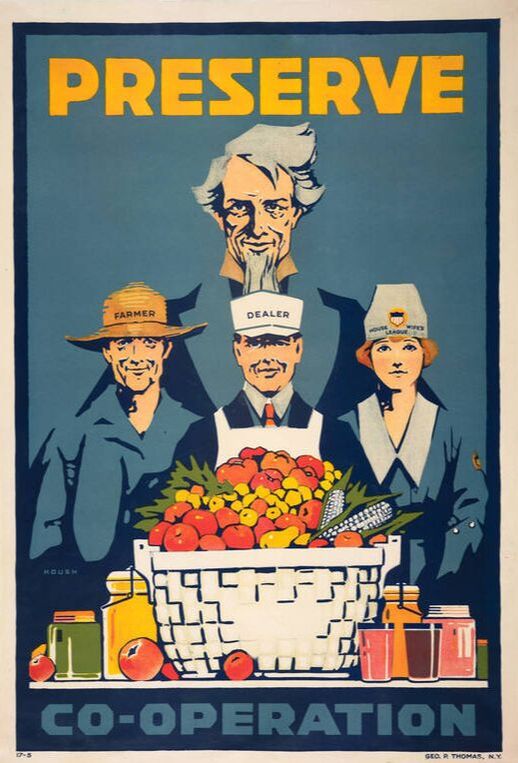

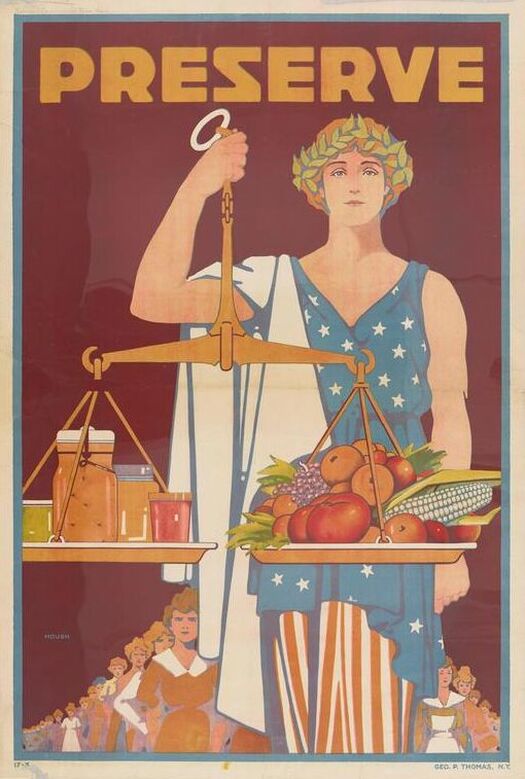

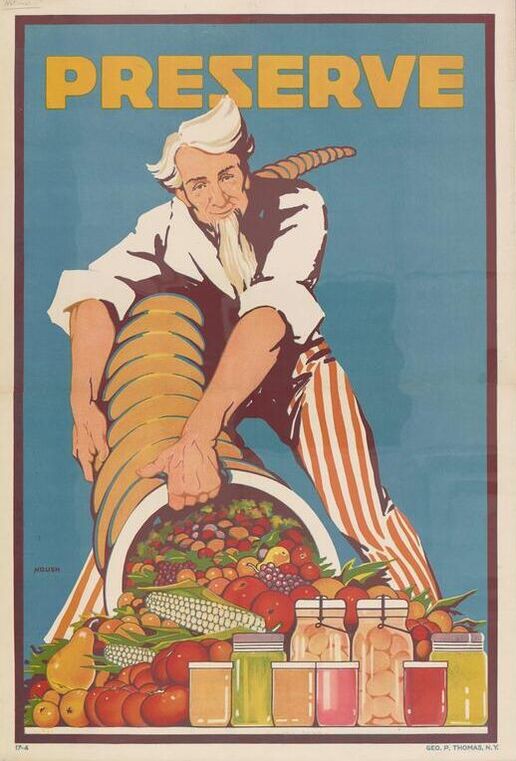

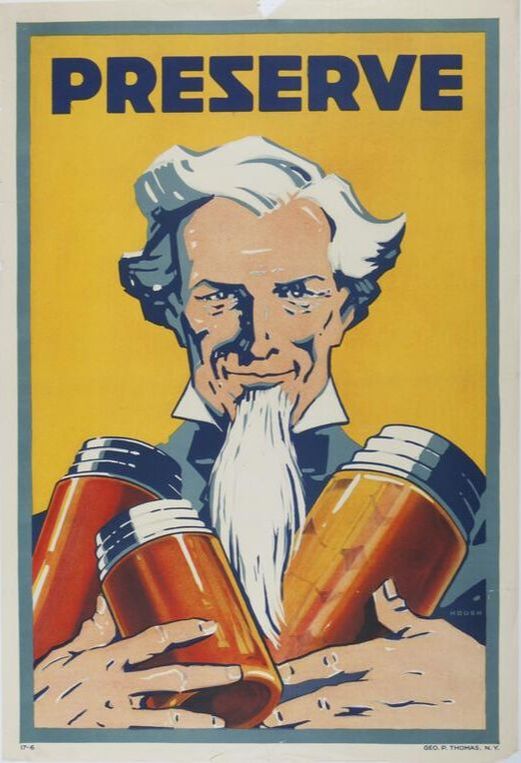

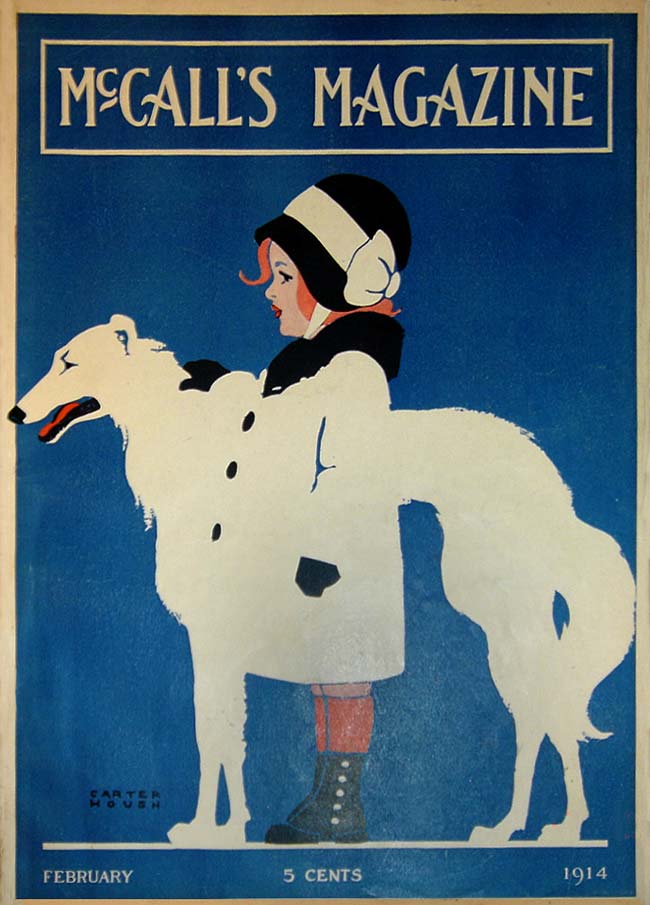

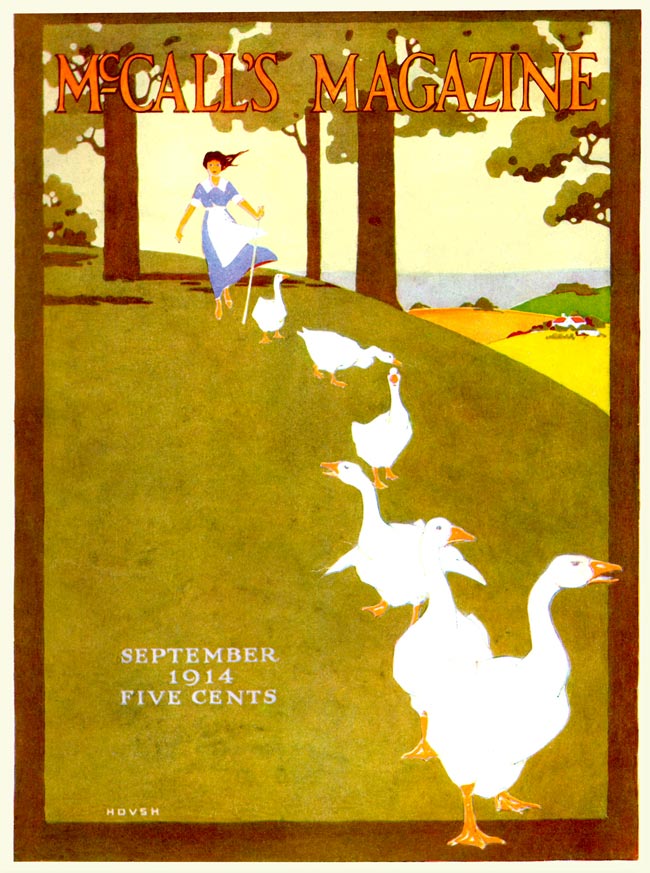

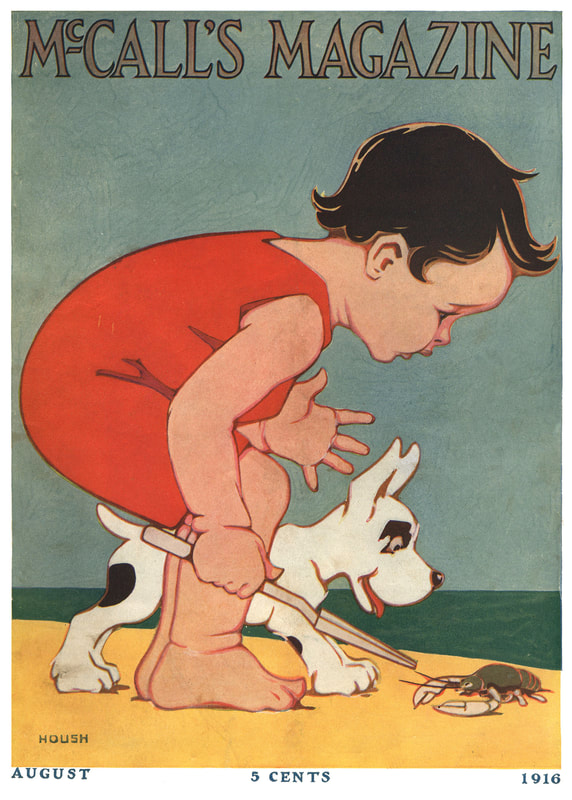

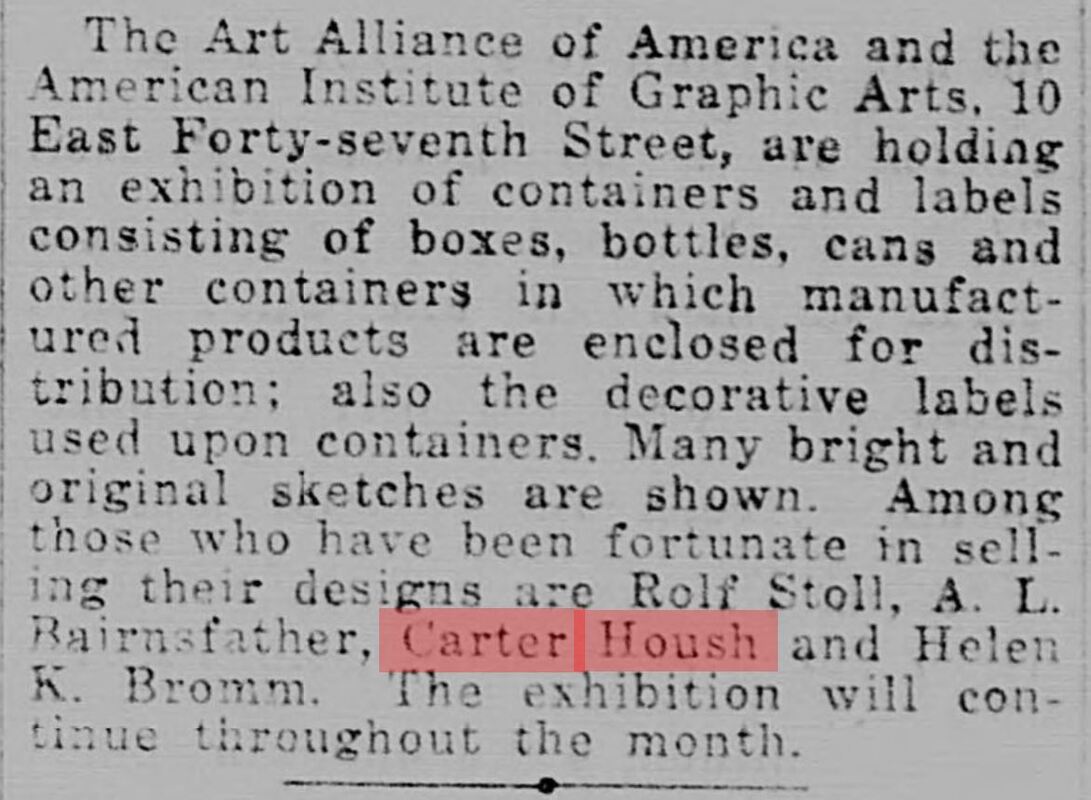

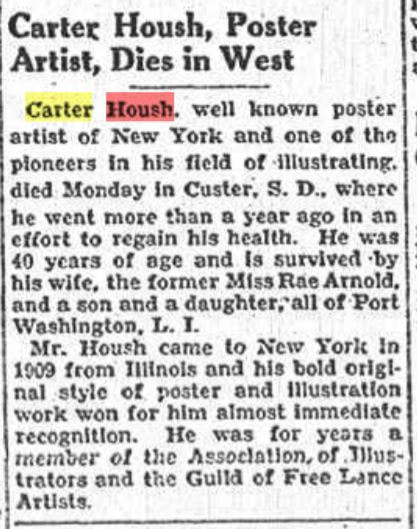

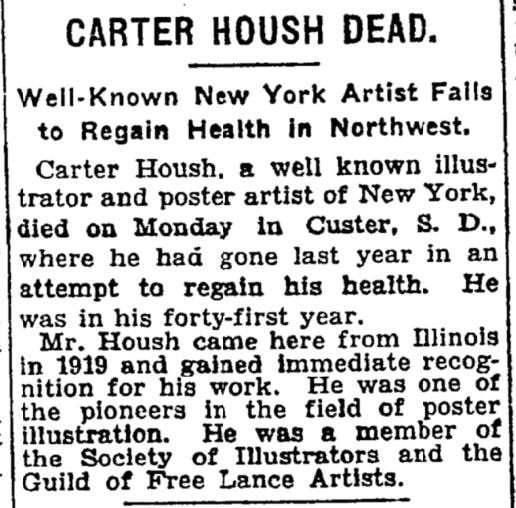

Note: This article was originally published on February 12, 2020 and has been updated with new information! If you haven't figured it out by now, I really love propaganda posters. Especially those from World War I. But my absolute favorite poster artist is one no one seems to know anything about.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, Uncle Sam, in his trademarked striped trousers but without his blue frock coat stands in his shirtsleeves, rolled up to the elbow, holding baskets full of fruit. Behind him is a table laden with full canning jars, with fruit and vegetables overflowing a pile beneath the table and behind that an army of women all dressed in blue. Missouri Historical Society. Carter Housh was apparently born in 1887 and died in 1928. And aside from an illustration or two for McCall's magazine, he is known ONLY for these six propaganda posters, encouraging Americans to preserve food during the First World War.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, a white-clad Columbia, goddess of America, with her French liberty cap and a star-spangled cape holds a massive tray laden with fresh fruits and vegetables. Below, an enormous handled saucepan and empty jars lined up before her, ready for filling. USDA Library Archive. As far as I can tell, nowhere else on the internet are all six of these posters displayed together. In fact, three of them were new to me! I discovered them as I was doing research on Housh, so that was delightful.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, Uncle Sam, again in his blue frock coat, looms behind three figures - a farmer in a straw hat, a "dealer" or greengrocer in white cap and apron, and a woman dressed in the official food preservation uniform with a white cap that reads "House Wife's League" stand before him. An enormous white basket of fresh produce, flanked by filled canning jars, sets on the table before them. Underneath reads "Co-operation," implying that preservation needs the cooperation of the farmer, the retailer, and the housewife, all under Uncle Sam's watchful gaze. Missouri Historical Society. Housh's work has been called "modern" before, but aside from the font with it's rather Z-looking S, the imagery and style seems very typical of the period. I love Housh's use of shadow and color-blocking and his depictions of produce are simply divine - perfect, gleaming, and blemish-free. Quite unlike the real world, alas. I particularly enjoy Housh's depictions of people and Uncle Sam is no exception. Uncle Sam was long used to represent the United States, but during the War James Montgomery Flagg's depiction in his famous "I Want YOU!" poster helped lead to a resurgence in use of Uncle Sam to represent the U.S. I'm particularly fond of Housh's version because he's less scrawny and stern looking than other incarnations. Plus, when he's hard at work, shirtsleeves rolled up, his hair gets a particularly nice wild swoop to it. One that isn't present in his more sedate depictions, like the poster below. One interesting thing about this time period is that both Uncle Sam and Columbia were used to represent the United States. The First World War is one of the last times the Greek-inspired secular goddess would be broadly used to represent America.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. In this image, a different incarnation of Columbia, in a gown of star-spangled blue, red and white stripes, with a white draped sleeve and a crown of laurel, holds enormous scales depicting canned goods and fresh produce in balance. Lined up behind her stretching out into the distance is a variety of American housewives in varying dress. USDA Library Archives. As much as I love Uncle Sam, of course I prefer Columbia because she is just so Progressive Era - an inspiring mix of Greco-Roman, feminist, Romantic representation that doesn't exist anymore. Of course, today's American goddess would look quite a bit different, and probably would not be named after Columbus, and that's equally as wonderful. If you want to know more about Columbia, check out this overview from the Atlantic. Which of these beautiful posters is your favorite? And if anyone happens to find anything on Carter Housh (or his printer, George P. Thomas of New York), please send me the info! Update - more about Carter Housh!Apparently Susan Jackson took my request to heart! Here's what she has to say about Carter Housh, her grandfather! Carter Housh was my mother's father. He was married to Rae (Arnold) Housh Enright. He died when my mother, Barbara Belle (Housh) Gibson, was 13. He left due to illness and went out to South Dakota where he died. He also had a son, David Paine Housh, my mother's younger brother. His wife, Rae, remarried another artist, a political cartoonist and author of children's books, Walter J. Enright. I do not have much information on Carter otherwise, sadly, nor do I have a good picture of him (so far.) Thank you, Susan, for sharing this great biographical info! I did do a little more digging to see what else I could find and I did find a few more references, although fewer than you might expect. In 1910 he appeared to work as an illustrator for the Sunday edition of the Buffalo Times based out of Buffalo, New York. He also worked for several years for McCall's magazine between 1910 and 1916, leaving evidence of several magazine covers, courtesy Flickr and Magazineart.org, a delightful website mentioned in one of the Flickr postings. We see no further known references to Carter Housh until 1918, the height of the U.S. involvement in World War I, when he is mentioned in an exhibition of artists as one of the few people who sold designs. 1918 is also the date attributed to his stunningly beautiful "PRESERVE" poster series. The Art Alliance of America and the American Institute of Graphic Arts, 10 East Forty-seventh Street, are holding an exhibition of containers and labels consisting of boxes, bottles, cans and other containers in which manufactured products are enclosed for distribution; also the decorative labels used upon containers. Many bright and original sketches are show. Among those who have been fortunate in selling their designs are Rolf Stoll, A. L. Bairnsfather, Carter Housh, and Helen K. Bromm. The exhibition will continue throughout the month. Carter Housh died on Monday, May 14, 1928 in Custer, South Dakota. Two obituaries in New York newspapers were published, likely due to his connections to New York City and Buffalo, NY when he was an illustrator. One, "Carter Housh, Poster Artist, Dies in West," published in the New York Sun on May 16, 1928 reads: Carter Housh, Poster Artist, Dies in West Another obituary, "Carter Housh Dead," was published in the New York Times, also on May 16, 1928. Carter Housh Dead Clearly the New York Times was less interested in accuracy than the Sun. It is sad to learn his life was cut so short and one wonders what illness he died of. Still, he leaves a legacy of stunning art and his posters remain my favorites of the entire war. If anyone finds any more breadcrumbs, send them my way and I'll update again! And, as always, if you enjoyed this post, please consider becoming a member of The Food Historian. You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

George Washington Carver is a historical figure you may have heard of. Perhaps you grew up learning in elementary school that he invented peanut butter (he didn't), or perhaps you know his work in popularizing sweet potatoes. You might know he was born into slavery, and through his pioneering efforts at plant science, helped found the agricultural college at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

But the bulk of his accomplishments have been glossed over in popular culture, until now. Grist recently published an excellent overview of the real contributions Carver made, and why they have largely been ignored. George Washington Carver died on January 5, 1943. Just a few months before his death, he published Nature's Garden for Victory and Peace, his contribution to the victory garden conversation during the Second World War.

Many people wrongly attribute Carver's booklet as a guide to victory gardens. In fact, it is a guide to foraging, and in line with Carver's ideas about food sovereignty that were decades ahead of their time.

Carver knew that access to land meant access to food, and even if Black families were denied access to land to grow gardens, they could forage in the wild public spaces or unclaimed verges of roads, edges of fields, etc. Still coming out of the Great Depression in 1941, people were eager to supplement often meager food supplies however they could. Free food was worth the labor to collect and process it. Nature's Garden lays out not only the common and botanical names of many wild-growing and native greens and herbs, some with accompanying line drawings, but also advice for harvesting and processing, recipe suggestions, and advice on drying garden produce for long-term storage - cheaper and easier than canning, which required expensive equipment and jars. Carver also includes references to Indigenous food uses, such as the use of sumac in making "lemonade," and directions for how to make "Lye Hominy," using the nixtamalizing process invented by Indigenous peoples in Mexico to hull corn and make the naturally-occurring niacin in the corn absorbable by the human body. The booklet was given away free - one copy per person. Additional copies could be acquired at the cost of printing. A Simple, Plain, and Appetizing Salad

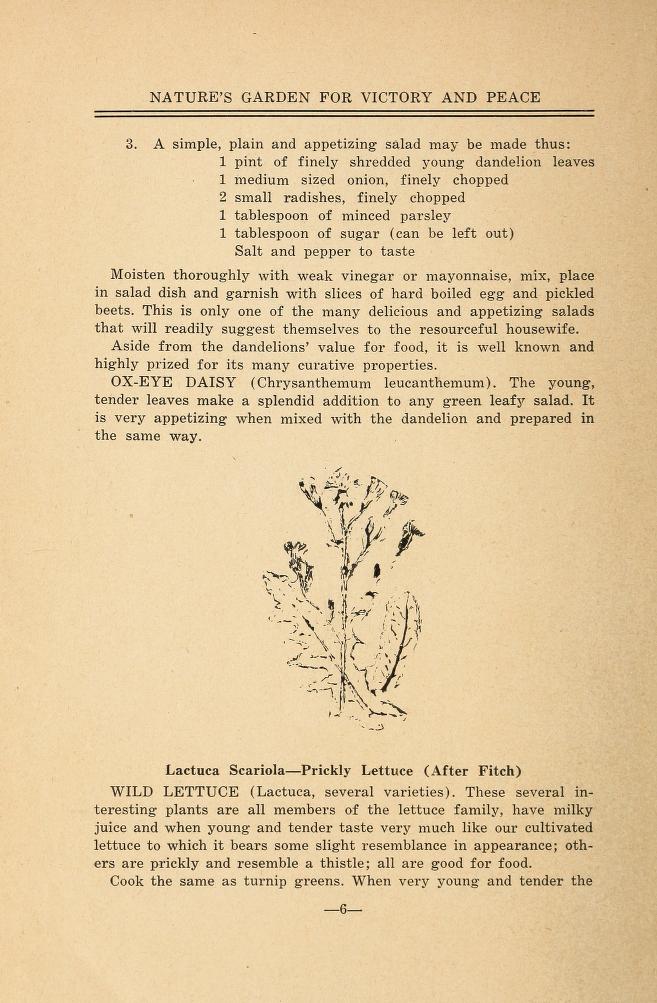

One of the few recipes Carver actually outlines in Nature's Garden is also one of the first - a recipe for dandelion salad.

It reads: "A simple, plain and appetizing salad made be made thus: 1 pint of finely shredded young dandelion leaves 1 medium sized onion, finely chopped 2 small radishes, finely chopped 1 tablespoon of minced parsley 1 tablespoon of sugar (can be left out) Salt and pepper to taste "Moisten thoroughly with weak vinegar or mayonnaise, mix, place in salad dish and garnish with slices of hard boiled egg and pickled beets. This is only one of the many delicious and appetizing salads that will readily suggest themselves to the resourceful housewife." A modern incarnation might be made with arugula, instead of dandelion leaves, if you are unable to forage your own safely.

Today, other foragers are trying to reclaim foraging for BIPOC communities. Alexis Nikole Nelson, also known as Black Forager, is one of those people. Like Carver, she reminds everyone that foraging has been the purview of BIPOC communities for as long or longer than the white male foragers who often get all the attention these days.

I love Alexis' near-daily posts and how she cooks the food she forages - the most important information and often left out of the foraging equation. She's been profiled by TheKitchn, and Civil Eats, but you can learn the most by just following her on Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, or Facebook. You can also support her work by becoming a patron on Patreon! Further Reading

To learn more about George Washington Carver, check out these excellent resources.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

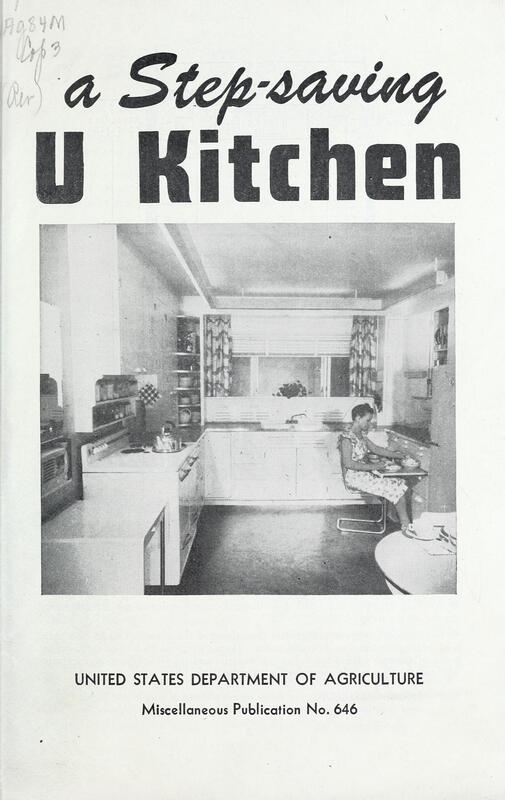

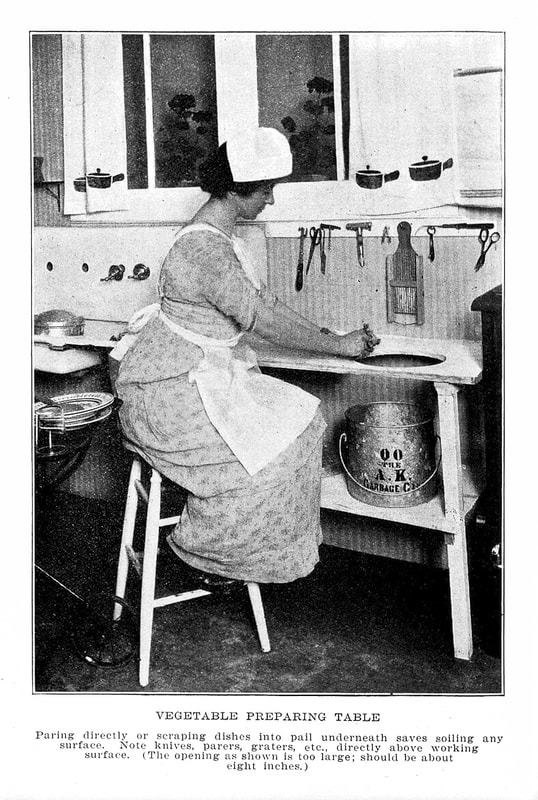

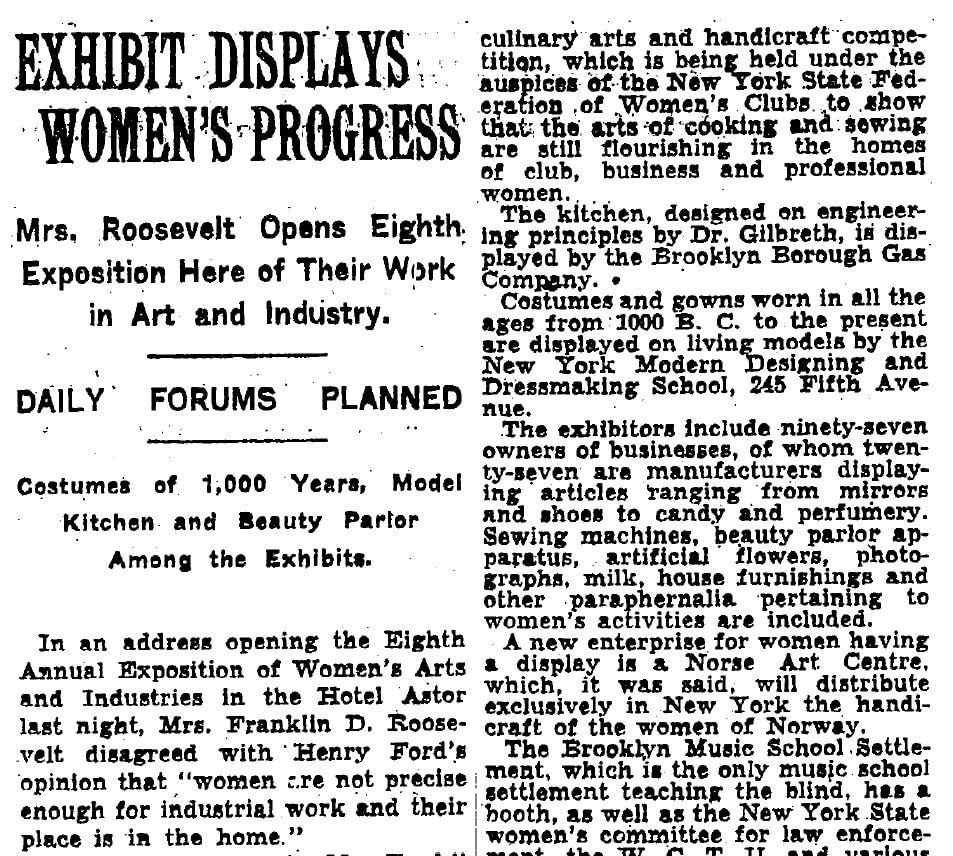

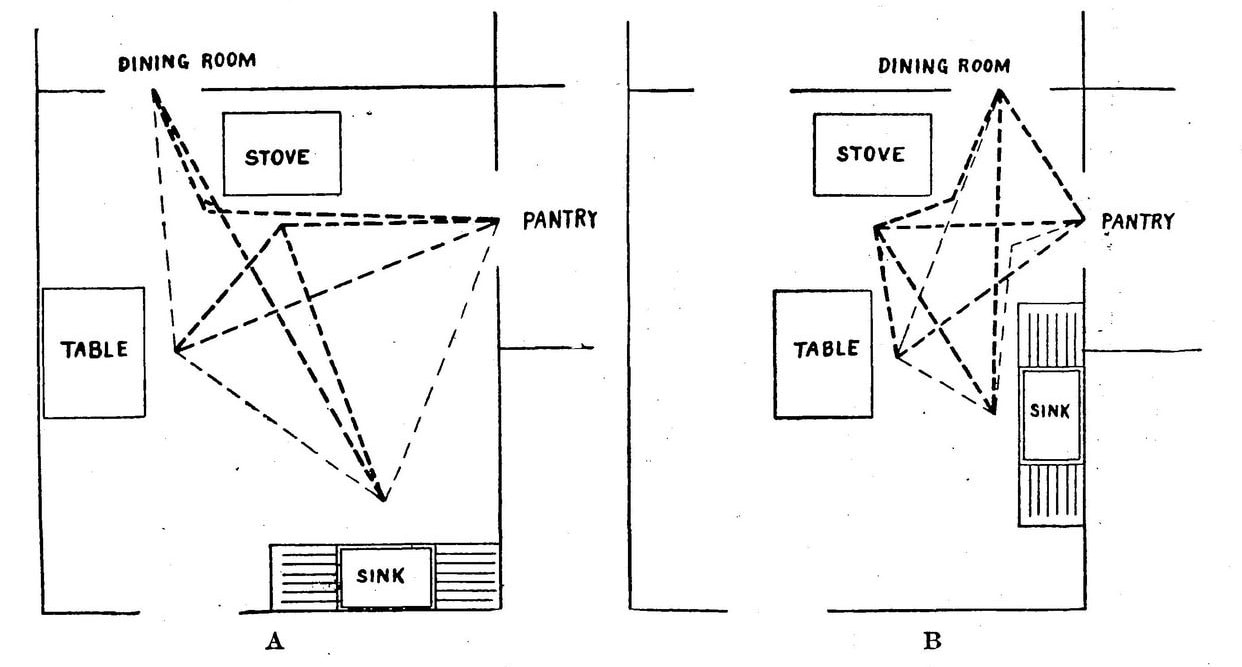

The other night I introduced a friend to one of my favorite YouTube videos ever. It’s a 1949 film put out by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Home Economics. You can watch the whole thing below: I love this film for a variety of reasons, but the primary one is how incredibly FUNCTIONAL this kitchen is. Not everything is perfect. The “messaging center” is too close to the stove for me – too able to collect splatters and grease from cooking. And the table, while nice, I think would have been better served by a more efficient built-in breakfast nook. But everything else? I LOVE IT. The storage is incredible. Everything is built with thought to use and efficiency. From the cooking and cleaning activities to the storage. And while the cabinets aren’t the prettiest, keep in mind that the design is meant to be built by farmers and handy homeowners – not professional contractors. Learn more about the film and the pamphlet for the Step-Saving Kitchen. This kitchen design is the culmination of several decades of work studies. During the Progressive Era, American interest in science began to increase, and scientific theories were applied to everything from factories to households. The Efficiency Movement was part of this application of scientific principles to everyday life. Led by mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor, the movement posited that everyday life, from industry to government to households, were plagued by inefficiencies, which wasted time, energy, and money. It also influenced the ecological conservation movement, a reaction to overuse of natural resources, and President Teddy Roosevelt was a known proponent. The movement, which became known as “Taylorism,” was hugely influential and spurred Progressive Era trust in experts and authorities that continued until the 1960s. Nowhere was Taylorism probably more influential than in the home economics movement, which advocated for efficiency in everything from nutrition to childrearing to household design. And that was thanks in part to the work of Christine Frederick, who in 1912 took Taylor’s principles and applied them to the household with a series of articles on “New Housekeeping” she wrote for the Ladies’ Home Journal. She started a Taylor-style efficiency laboratory in her own home kitchen and went on to publish several more books on the subject, including the 1919 Household Engineering: Scientific Management in the Home. Another influential advocate of household efficiency was psychologist Lillian Gilbreth. With her husband Frank Gilbreth, the two created a partnership to take Taylor’s ideas and apply them to industrial spaces, developing time-and-motion studies. Today, you might know them best as the parents who starred in the book (and subsequent films) Cheaper by the Dozen. After Frank’s untimely death in 1924, Lillian encountered discrimination in the engineering field, and began to turn her talents toward the domestic sphere. Partnering with Mary E. Dillon, president of the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company (and the first female utility president in America), Gilbreth and Dillon developed the kitchen work triangle, which advocated for a step-saving triangle between sink, stove, and refrigerator. Part of Gilbreth’s Practical Kitchen, the new design was revealed at the Eighth Annual Exposition of Women’s Arts and Industries on October 1, 1929. Eleanor Roosevelt was one of the speakers. Many of these principles were adopted by government organizations like the USDA. As early as the 1909, with the federal government’s Country Life studies, the plight of farm women and their poorly designed, technology-lacking kitchens came to light. The USDA’s Farmer’s Bulletin No. 607, “The Farm Kitchen as Workshop,” published in 1921 by Anna Barrows, outlined some of the concerns about kitchen efficiency and how to correct them. Page 10 of the bulletin illustrated the difference in closing the distances between workspaces – a star shape similar to the kitchen work triangle resulted. Several Congressional Acts brought federal funding to these studies. The Smith-Lever Act of 1914 mandated home economics instruction at land grant colleges. The Purnell Act of 1925 allocated federal funding into vitamin research and research of rural home management. These types of studies flourished under the federal funding and in my opinion placed overdue emphasis on the safety, sanitation, comfort, and efficiency of the home. All of these efficiency studies contributed to the result of the 1949 kitchen I love so much. But what happened? Why do modern kitchens seem to ignore the best research of the past? Today, there is far less government investment in domestic study – either from the USDA or public universities. The USDA’s Bureau of Home Economics was shuttered in 1962. Some of its personnel were shifted to the Nutrition and Consumer-Use Research department under the auspices of the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. Some consumer-based research regarding food was absorbed by the FDA. But the kitchen research seems to have largely been abandoned. Some universities, like at Cornell, have continued to offer household design programs as subsets of architectural programs. But the federal funding is gone. Which is a shame, because our household lives seem to have suffered for it. One rule that has been adopted most widely is the kitchen work triangle. But not always. For instance, my kitchen doesn’t have one – the refrigerator, stove, and sink are all in a line. The only triangle is that my primary work surface is on the other side of my galley kitchen. And don’t even get me started on the ergonomics of storage. Those seem to have been discarded wholesale. One ray of light has been the resurgence of roll-out shelves. But even these are few and far between, likely because they are more expensive than traditional fixed shelving. And yes, dear reader, here, I think, is the rub – efficient kitchens must be custom designed. And in our cookie-cutter, prefab world, both design and customization are expensive. In addition, many of today’s kitchens are designed more for show, or occasional entertaining, rather than daily life. Which is an unfortunate reflection of how many Americans cook (or don’t). Case in point: the disappearance of the pantry – the one final thing that 1949 kitchen doesn’t have (it’s presumably in the cellar in the film) that I’d want. At any rate, if I ever win the lottery, you know what kind of kitchen I’ll be building. What aspects of the 1949 Step-Saving Kitchen did you like best? What would your dream kitchen look like? Sources & Further Reading

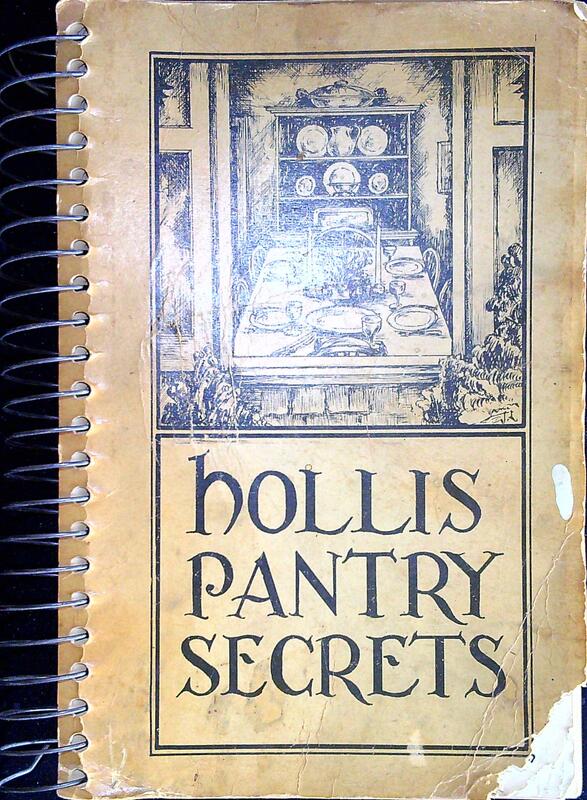

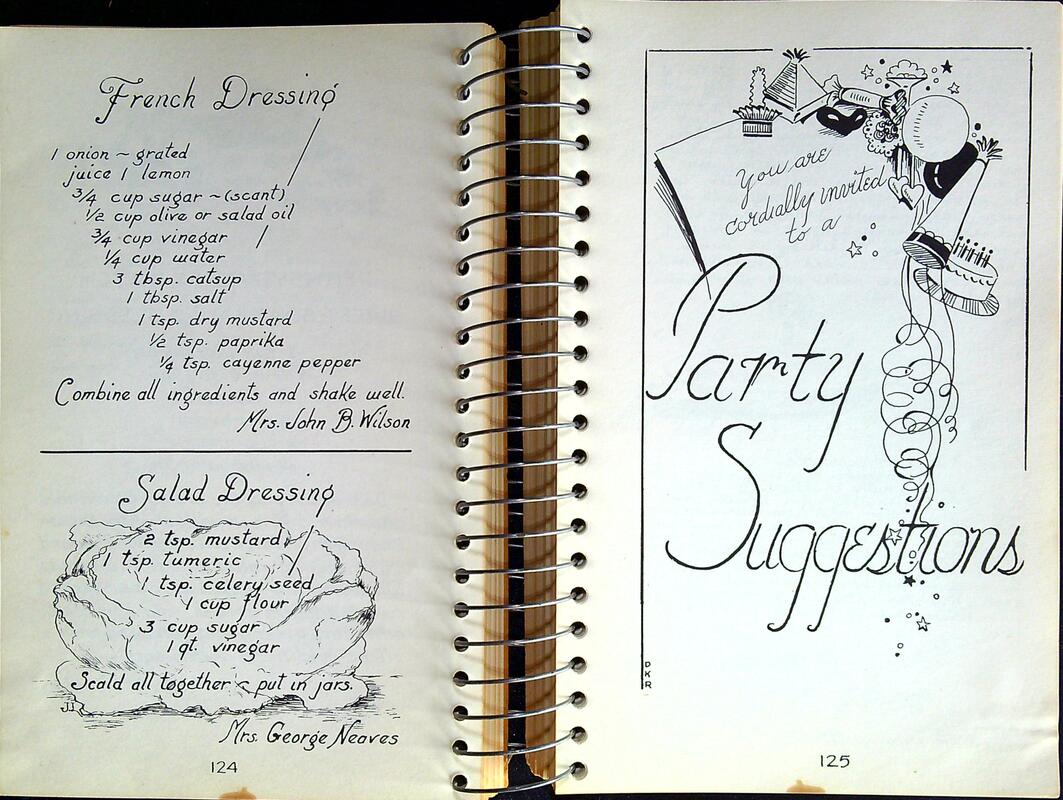

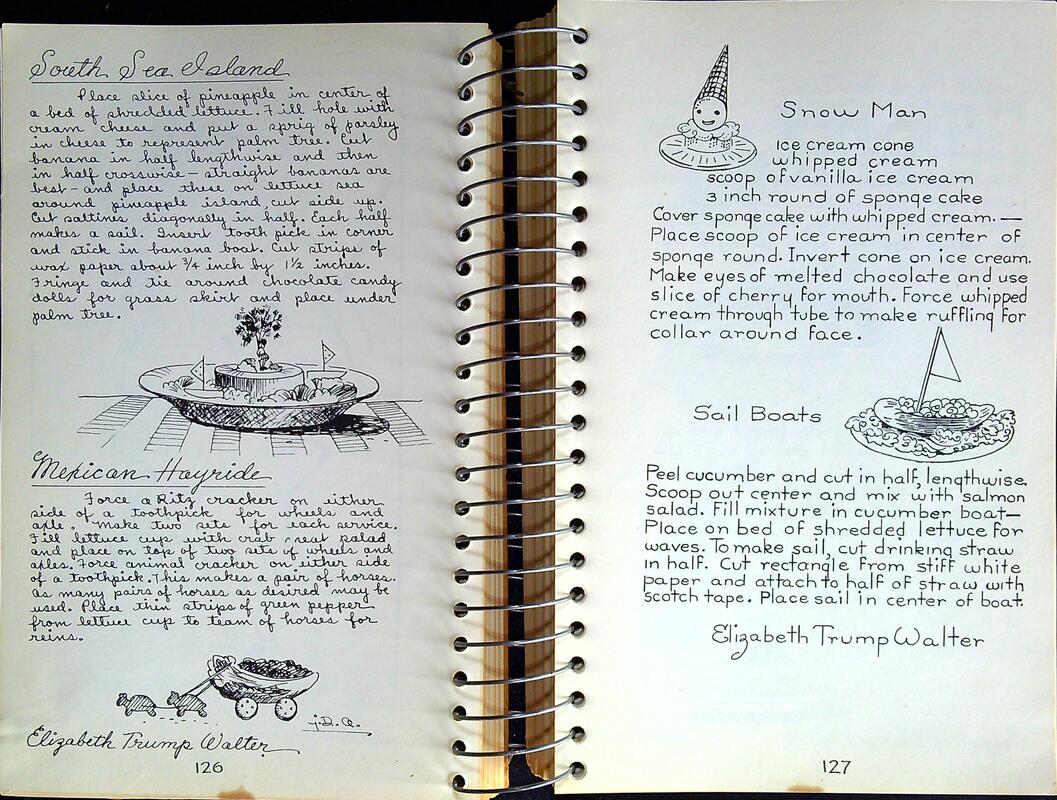

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! In 1946 the Women's League of the Hollis Presbyterian Church in Hollis, NY published this community cookbook, Hollis Pantry Secrets. Hollis is a neighborhood in Queens County, NY and in the 1940s was a relatively new development of single-family homes that had only been part of New York City since 1898, when it was developed from rural farmland. I was in the process of digitizing the cookbook when I ran across a somewhat familiar name. "Elizabeth Trump Walter." Could it be? Was she related to President Donald Trump? I started digging, but sadly, there wasn't much to find. Elizabeth was born in 1904 to Elizabeth Christ and Frederick Trump (Sr.), German emigrants to the United States. Frederick (sometimes spelled Friedrich) had made his fortune during the Gold Rush with a hotel specializing in alcohol and suites for prostitutes. He returned to Germany in sometime before 1902, only to run into trouble with the authorities, who deemed his emigration illegal because he had not completed his military service. He met and married Elizabeth Christ in 1902 and they moved to New York City. In 1904, homesick Elizabeth convinced him to return to Germany, but due to Frederick's trouble with the authorities over his lack of military service, they could not stay, and returned to New York City in 1905. It is unclear if Elizabeth the younger was born in Germany or not. Her younger brother Frederick Jr. was born in 1905 and John in 1907. Frederick Trump Sr. died of Spanish Influenza in 1918, and the family was soon in trouble financially. Elizabeth Christ Trump decided to continue her husband's work in real estate development, and that her children would be her primary employees. Elizabeth the younger was also the eldest child - she left high school to attend secretarial school so that she could be the accountant for the newly formed E. Trump and Son company. Her youngest brother John was to be the company architect. Fred Jr. the builder. John left the company early on and Fred Jr., with his mother, built E. Trump and Son into a real estate empire. Derailed by the stock market crash of 1929, when E. Trump and Son officially went out of business, by 1934 Fred Jr. managed to finagle his way into a mortgage-servicing contract, and the Trumps were back in the real estate business. The rest is fairly well-known history, including Trump's housing discrimination. But what about Elizabeth? Her history is almost non-existent. She has no Wikipedia page. She isn't even mentioned on her mother's Wikipedia page, despite the fact that Fred Jr. is noted as the "second child" and John the "third." She is mentioned on the Trump family page. We know she married William Walter, who was training to work in a bank, in June of 1929. According to William's 1959 obituary, he was a veteran of World War I who had worked in banks starting as a page boy in 1910. The year he and Elizabeth were married, he was made assistant secretary of the newly formed Manufacturer's Trust. Elizabeth apparently continued in her accounting role after marrying William, but it is unclear whether she left in late 1929 when E. Trump and Son went under, and whether she continued to work under Fred Jr. Elizabeth and William Walter had two children - William Trump Walter, born in 1931, and John Whitney Walter, born in 1934. Both Elizabeth and William Sr. were highly involved in the Hollis Presbyterian Church. He was an elder, she, a member of the Women's League. So it makes sense that Elizabeth would submit recipes for the 1946 cookbook. Here are her recipes: The "Party Suggestions" that start on page 125 is a small section that only contains recipes from Elizabeth Trump Walter! All variations on starter salads (with one exception), probably for ladies' luncheons, but possibly also for themed dinner parties, or even children's parties. South Sea Island Place slice of pineapple in center of a bed of shredded lettuce. Fill hole with cream cheese and put a spring of parsley in cheese to represent palm tree. Cut banana in half lengthwise and then in half crosswise – straight bananas are best – and place these on lettuce sea around pineapple island, cut side up. Cut saltines diagonally in half. Each half makes a sail. Insert tooth pick in corner and stick in banan boat. Cut strips of wax paper about ¾ inch by 1 ½ inches. Fringe and tie around chocolate candy dolls for grass skirt and place under palm tree. Mexican Hayride Force a Ritz cracker on either side of a toothpick for wheels and axle. Make two sets for each service. Fill lettuce cups with crab meat salad and place on top of two sets of wheels and axles. Force animal crackers on either side of a toothpick. This kames a pair of horses. As many pairs of horses as desired may be used. Place thin strips of green pepper from lettuce cups to team of horses for reins. Snow Man Ice cream cone Whipped cream Scoop of vanilla ice cream 3 inch round of sponge cake Cover sponge cake with whipped cream. – Place scoop of ice cream in center of sponge round. Invert cone on ice cream. Make eyes of melted chocolate and use slice of cherry for mouth. Force whipping cream through tube to make ruffling for collar around face. Sail Boats Peel cucumber and cut in half, lengthwise. Scoop out center and mix with salmon salad. Fill mixture in cucumber boat – Place on bed of shredded lettuce for waves. To make sail, cut drinking straw in half. Cut rectangle from stiff white paper and attach to half of straw with scotch tape. Place sail in center of boat. Easter Eggs in Nests Place slice of pineapple on small bed of shredded lettuce. Divide cream cheese into five parts. Color each part a different pastel shade, leaving one white. Form cream cheese into small eggs, the size of a robins egg and place in center of pineapple slice. Circus Salad Cut a five inch circle from a piece of stiff paper with pinking shears. Cut a slit to center from one side and then put together to form a dome shaped piece for top of tent. Place tuna fish salad in center of plate. Around salad sprinkle Cornflakes or Rice Krispies to represent sawdust. Insert five pretzel sticks around salad and place tent on top of these sticks. Her six party suggestions make up the entire "Party Suggestions" chapter. I, personally, would have a hard time cutting saltines in half or forcing toothpicks into crackers, so clearly this sort of thing took a great deal of finesse. Elizabeth Trump Walter died on December 4, 1961, at the age of 57, "after a long illness," just two years after her husband William. Her obituary is on page 37 of that day's New York Times, towards the bottom. She pre-deceased her mother Elizabeth Christ Trump by five years. Ironically, Elizabeth Christ Trump does not have an obituary in the New York Times, she is only listed among the deaths recorded on June 9, 1966 - her notice submitted by the Federation of Jewish Philanthropics. According to Elizabeth's son John Walter's 2018 obituary, the Walters moved to Manhasset, NY toward the end of their lives. They lived in a retirement home built by the Walters and likely Fred Trump, Jr., but died just a few years later. John begun attending the Congregational Church of Manhasset at his mother's behest. Elizabeth Trump Walter was memorialized with a restored organ at the Congregational Church of Manhassett, NY sometime in recent years. Elizabeth Trump Walter rarely shows up in Trump family histories, probably because of her early death compared with the Trump family fortunes. But it was a fascinating project to track down what I could about her. The Hollis Pantry Cook Book has more secrets and famous recipe authors to share, so stay tuned for future blog posts. Have you ever found a famous person's name in a community cookbook? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 24 of the Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made eggnog and talked about all things Christmas, including Medieval beverages, the origins of fruitcake, plum pudding, and mincemeat. Full list of historic Christmas beverages below, and here's a little more history on the Eggnog Riot of 1826 at West Point! We also talked briefly about Charles Dickens (hence the Fezziwig image!) and the 2017 movie "The Man Who Invented Christmas," which I recommend!

(Apologies for the fuzzy audio - not sure what happened!)

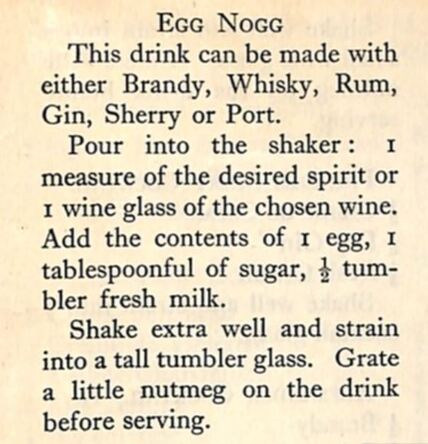

A LOT of historic recipes for eggnog call for party-sized portions. But there are lots of single-serve versions in vintage bartender's guides through the ages. I thought we would use this one, Practical Bar Management, by Eddie Clark, published in 1954, which, co-incidentally, is also the same year the movie White Christmas came out. If you'd like to catch up with the menu I put together to go along with White Christmas, you can see all the blog posts and recipes here.

Eggnog (1954)

As you can tell, this recipe isn't exactly exact! Not even the spelling. Here's the original text:

"This drink can be made with either Brandy, Whisky, Rum, Gin, Sherry, or Port. "Pour into the shaker: 1 measure of the desired spirit or 1 wine glass of the chosen wine. Add the contents of 1 egg, 1 tablespoonful of sugar, 1/2 tumbler fresh milk. "Shake extra well and strain into a tall tumbler glass. Grate a little nutmeg on the drink before serving." Here's my adaptation, which I shook over ice to make it cold, which I think watered things down a smidge. Still very good. 1 jigger spiced rum 1 pony bourbon 1 large egg, well-washed 1/2 cup whole milk 1 tablespoon sugar Shake very well until cold and frothy. Grate some fresh nutmeg on top and serve cold. I am not generally a fan of prepared eggnog you can buy in stores. It's usually thickened with carageenan, VERY sweet, and very strongly flavored. This homemade version was much nicer - not as thick (although you could use half and half or light cream instead of milk for a richer product and skip the ice), not nearly as sweet, and although the alcohol was very forward (you could cut back a bit if you want), it was quite nice - creamy with a frothy head and didn't taste much like eggs at all, surprisingly. I'm a fan! Holiday Beverage Glossary

A LOT of different holiday beverages came up in the comments, so I thought I'd list a few with approximate ages and places of origin.

So what do you think? Did I miss any historic holiday beverages? At our house, we always serve an 18th century punch called Second Horse Punch. Which, like most Christmas classics, needs to be made in advance! Do you have any special or traditional holiday beverages? Share in the comments!

Food History Happy Hour and the Food Historian blog are supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

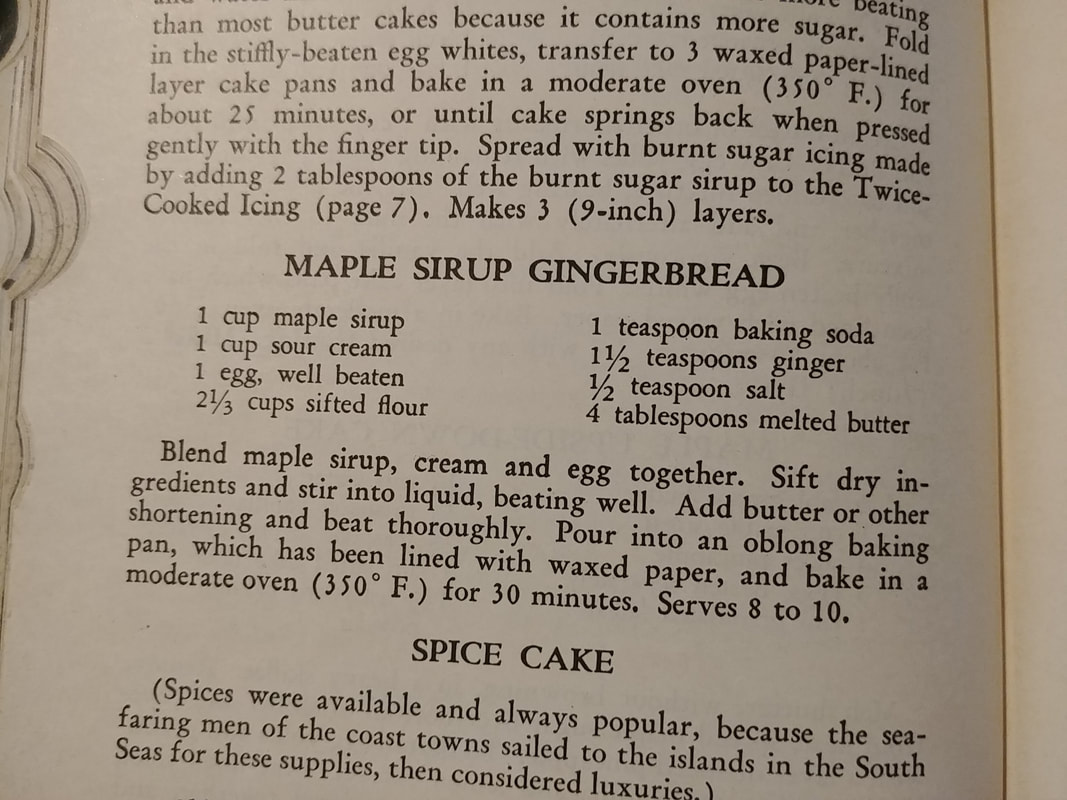

I really debated what dessert would go best with White Christmas. Aside from the malted milkshake, and the General's birthday cake, none are mentioned in the movie. I thought about going the fruitcake route, but I didn't exactly have time for it to soak. And then, when flipping through The United States Regional Cook Book (1947), I ran across a recipe I'd found and wanted to try earlier in the year - "Maple Sirup Gingerbread." Gingerbread is a traditional Christmas food dating back to the Medieval period, and the use of maple syrup (or, in 1940s spelling, "sirup") made the recipe appropriately Vermont-y. During World War II, maple syrup was touted as a sugar alternative and throughout history it has generally been less expensive than refined white sugar. Not so today, when a quart of maple syrup ranges in price from $15-$25, depending on where you are (which means a cup averages about $5). If you'd rather not "waste" a whole cup of maple syrup on a cake, feel free to use a different gingerbread recipe (may I recommend New York Gingerbread?). Maple Sirup Gingerbread (1947)It occurred to me after I started making this that the "sour cream" in the recipe was probably SOURED liquid cream, instead of the thick, dairy sour cream we're used to these days. But I went with it anyway. If you want to try something closer to the original, split the difference and use a half cup of heavy cream and a half cup of sour cream. Aside from that, I made no changes to this recipe, except to make an executive decision about "oblong baking pans" and just do a round one instead. I also don't recommend lining the pan with waxed paper, unless you want the wax to melt into your cake and onto your pans. Parchment is fine, but unnecessary. Just grease the pan well. 1 cup maple syrup 1 cup sour cream 1 egg, well beaten (you don't actually have to beat the egg in advance) 2 1/3 cups sifted flour (ditto sifting) 1 teaspoon baking soda 1 1/2 teaspoons ginger 1/2 teaspoon salt 4 tablespoons melted butter (1/2 a stick) Blend maple syrup, sour cream, and egg together until smooth. Add dry ingredients and whisk into the liquid ingredients, making sure to stir well. Add butter and beat thoroughly. Pour into greased ROUND cake pan and bake at 350 F for 30-40 minutes, or until the center of the cake springs back to the touch. Loosen the edges and tip out the pan to cool on a rack. Serve warm or cold with plenty of whipped cream. A word to the wise, you'll note that this recipe ONLY contains ginger, no other spices. But it contains quite a bit of ground ginger, which means the ginger flavor is very forward and in my opinion masks the flavor of the maple syrup, though my husband swore he could taste it. You might want to dial back the ginger a bit if you make it. Either way, it's very good - dense and moist with lots of good gingery flavor and feeling appropriately Christmassy. If you're trying to be healthier, I recommend subbing half of the all-purpose flour with a whole grain one. Spelt or rye would both be nice. So what do you think? Does Maple Sirup Gingerbread go with White Christmas (1954)? Let me know in the comments! And be sure to follow the White Christmas tag or visit the original menu post for the rest of the White Christmas Dinner and a Movie menu. Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! White Christmas has a famous scene about sandwiches. In it, Bing Crosby (playing Bob Wallace) waxes lyrical on the types of women he dreams about when he eats various sandwiches as a bedtime snack. Rosemary Clooney (playing Betty Haynes) teasingly asks him what he dreams about when he eats liverwurst. Bob shudders in response. I'll be honest - I've never had liverwurst. Some people love it, some people hate it. Maybe someday I'll try it, but my vegetarian friend saved the day. The phrase "lentilwurst" popped into my mind and I decided to run with it. This recipe is the only one that isn't based on a historical recipe (for obvious reasons), but lentils were around in the 1950s and were used as a vegetarian substitute for meat. This recipe also takes after slightly the infamous vegetarian bean loaves and nut loaves of the late 19th and early 20th century. In fact, one of the recipes I considered for the menu was "Boston Roast," which is a take on meat loaf, only made with beans (hence Boston) instead. I based my recipe loosely on this one, but with a few tweaks of my own. Here's my version, which you could easily make vegan by using olive oil or butter substitute, and vegan mayonnaise. Lentilwurst (a.k.a. Vegetarian Liverwurst)1 cup red lentils 1 1/2 cups water 1/4 cup butter (half a stick) 1 pint baby bella mushrooms 1 teaspoon dried sage (not ground - use 1/2 teaspoon if using ground) 1 teaspoon smoked paprika 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon ground mace (can use nutmeg instead) 1/2 teaspoon black pepper 1/2 teaspoon onion salt 2 heaping tablespoons mayonnaise Rye bread Dijon mustard In a 2 quart saucepan, bring lentils and water to a boil, then reduce heat and cook until lentils are very soft and have absorbed all water (watch out for boiling over and stir occasionally). Meanwhile, clean and finely mince mushrooms. When the lentils are done, remove to a glass dish to cool. Wash the same saucepan and add the butter and spices. When butter is melted, add mushrooms and cook over medium to medium-low heat until the juices and butter are largely reduced. Mix mushrooms, lentils, and mayonnaise until well combined. Chill in a glass container in the fridge. When ready to serve, slice or spread onto rye bread that has been thinly spread with mustard. Eat open faced or closed. The lentilwurst sandwiches were the surprise hit of the evening. Everything on the menu was good, but this was so good I was very sad I hadn't made a double batch, and have since gone out and bought more mushrooms precisely so I can make more. The mushrooms and lentils gave it a meaty texture, and the salty, spicy flavors of the seasonings went very well with the rye bread and mustard (traditional liverwurst sandwich ingredients). I did not add onions or pickled onions to the sandwiches as I had considered, but that would be another lovely addition. We gobbled this right up with no regrets. Do you think lentilwurst goes with White Christmas (1954)? Let me know in the comments! And be sure to follow the White Christmas tag or visit the original menu post for the rest of the White Christmas Dinner and a Movie menu. Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed