|

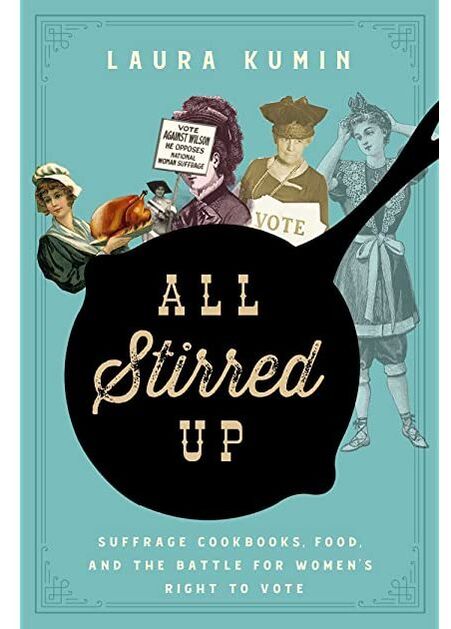

This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women’s Right to Vote, Laura Kumin. New York: Pegasus Books, 2020. 357 pp., $28.95, hardcover, ISBN 978-1-64313-452-9. ,I first learned about cookbooks associated with women’s suffrage thanks to this Atlas Obscura article and I was instantly fascinated. Feminism in the 20th century was often more interested in throwing off the chains of household drudgery than with enticing converts through snacks. But that is precisely the premise of All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women's Right to Vote, which is why I was so excited that I put it on my Christmas wish list. I was expecting a thorough examination of the suffrage cookbooks, the women who created them, and their place in the movement. Sadly, as a book, All Stirred Up is like an underdone cake – it looks perfect on the outside, but the inside is doughy and disappointing and could have used another 30 minutes in the oven. Laura Kumin is a former lawyer turned cooking educator and food writer. She does not have a historical background, and, as is the case with many non-historians who write food history, it shows. All Stirred Up begins, even before the introduction, with a lengthy timeline. While I find timelines to be incredibly useful, especially when dealing with complex chronology, starting the book with one was not a choice I would have made. It is confusing to the reader, who is presented lengthy and disparate facts without context or introduction. A lack of context is a theme for the book. Kumin’s introduction is part explanation of her interest in suffrage cookbooks and part layout of her main argument. She makes a compelling case that modern takes on suffrage history have largely ignored the role of cookbooks in converting skeptics to the cause. Unfortunately, this argument is not often revisited in the subsequent chapters. Most of the chapters are quite brief, some as few as eight pages, and while historical overviews abound, actual analysis is lacking. Taking up the most space are the recipe sections that follow each chapter, organized by type. Although these recipes are directly taken from the suffrage cookbooks, with modern adaptations designed by Kumin, there is no context for any of the recipes and no dates listed. Most recipe sections draw from multiple suffrage cookbooks without differentiating between them, beyond noting where the originals came from. We do not know why Kumin chose these particular recipes, how they reflected the cookbooks and times from whence they came, or even what, if any, relevance they had to the suffrage movement. For many chapters, the number of pages devoted to recipes outweigh the pages devoted to history. As for the history itself, most of it is shallow summaries meant to orient the reader to the basics of suffrage history, home economics and food science, and basic culture of the period. While this context is useful for non-historians, it seems to come at the expense of historical analysis. In addition, the chronology of the book is all over the place. The book begins in 1848, with an exercise in “time travel” in which Kumin writes in the present tense. Then zooms ahead to the Progressive Era and back again several times. At the end of Chapter 3, we’re already at the 19th Amendment in 1920, an achievement which is not really revisited for the rest of the book. Throughout the book, the suffrage movement in one decade is conflated with the same movement decades later. Little attention is paid to the context of national culture on the way in which the women's suffrage movement was operated, despite the fact that it was under operation, in one way or another, for over 70 years. Missed opportunities to make connections to other major movements, including abolitionism, Temperance (which is dismissed as detrimental to the cause, p. 78-79), Progressive reform, government regulation, etc., abound. Chapters 3, 4, and 6 are the strongest, content- and argument-wise. In Chapter 3, “From Seneca Falls to the Ballot Box,” Kumin examines the suffragists themselves and the post-Civil War resurgence of the movement. To her credit, she makes a point of mentioning African American suffragists and their shameful treatment by mainstream white suffragists, as well as male allies and the “antis” – anti-suffragists. However, points that needed more analysis were often presented as literal sidebars in the text. For instance, noted suffrage ally Frederick Douglass, instead of being included in the main text, receives a short summary in a gray box. The Beecher family get similar treatment in a sidebar about how the movement split families. Catharine Beecher, a fervent anti-suffragist, was a cookbook author and young women’s educator of some renown and who, despite conflicting ideas about suffrage, nonetheless co-wrote The American Woman’s Home with her suffragist sister. Cookbook author, fervent abolitionist, and Native American rights activist Lydia Maria Child is mentioned in a quotation, but otherwise ignored. These are just a few of many missed opportunities to engage with the subject matter more deeply – discussing how both suffragists and “antis” used women’s work and the home in their arguments for and against suffrage. Chapter 4, “We Can Peel Potatoes and Fight for the Vote, Too! Suffrage Strategies and Battle Tactics” is the strongest chapter in the book, and one of the few that cites primary sources in the endnotes. Discussing the divergent tactics between “mainstream” and “militant” suffragists, Kumin compares the mainstream work of the cookbooks, cafeterias, the “doughnut campaign,” a “Pure Food” storefront, and cooperating with agricultural extension, to the militant tactics of parades, protests, arrests, and hunger strikes. Unfortunately, she does not define who exactly is “mainstream” and who is “militant,” except to note differing tactics. Kumin argues that the more mainstream feminists were more successful in changing hearts and minds, but presents little evidence to back up this claim. In addition, despite covering the bulk of the Progressive Era, the chapter mentions, but gives little context to agricultural extension, the Temperance movement, home economics, World War I, and women’s clubs. An overview of home economics and food science comes in the following chapter, “Revolution in the Kitchen.” Chapter 6 finally addresses the cookbooks themselves, with an overview of how they were financed, celebrity contributors, and how the recipes included were reflective of the periods in which they were published. The cookbooks are still dealt with in generalizations, however, and their individuality is lost in the mix. The section on celebrities, although interesting contains another missed opportunity, as Kumin mentions one recipe contribution from noted feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, but not her dislike of cooking. In the section on funding, Kumin clearly notes that the cookbooks were usually designed as fundraisers for the organizations, a fact that belies her argument that cookbooks were meant to convert, though she does note they were sometimes also used as enticing premiums for subscriptions. Chapter 7 is a brief discussion of how suffragists used dinners and entertaining to support the cause. All Stirred Up ends without a clear conclusion, instead relying on Chapter 8, “What Suffrage Means for Us,” an eight-page summary of women in American politics since 1920. This final chapter makes no clear reference to the influence of the cookbooks that purportedly drove the suffrage movement and does not sum up the arguments outlined in the introduction. It is followed by 28 pages of dessert recipes. There is no explanatory postscript, only Kumin’s acknowledgements. In all, All Stirred Up does make a good point about the role of suffrage cookbooks in the movement, but it fails to back up its few arguments convincingly, particularly in light of the use of community cookbooks as fundraising tools, rather than modes of conversion to the cause. Instead of concentrating the bulk of her argument into Chapter 4, Kumin would have had a much more compelling book had she spread that argument throughout all the chapters, addressing the role of domesticity from the perspectives of both the suffragists and the antis. More primary source analysis would have enriched the narrative. Looking at the writing of major suffrage leaders to determine their personal opinions on cooking and domesticity would have added depth to her arguments. Examining the cookbooks themselves, their recipes, and the organizations and women that produced them as a chronological accounting of the movement, would have added greatly to the coherence and context of the book. Had the recipe sections been introduced by era, with headnotes and historical context for each recipe, their inclusion would have made the book both stronger and appealing to the general public. Ultimately, the book feels as though it was rushed to print, possibly to coincide with the centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 2020. If you are unfamiliar with basic suffrage and food history, this may provide some good historical summaries and Kumin’s research on the 1909 Washington Women’s Cook Book is particularly strong. But, if you were hoping for a well-written, well-organized examination of the role of food in the suffrage movement and the influence of suffrage cookbooks, as I was, you’ll be sorely disappointed. I can only hope that future historians can expand on Kumin’s work. If you'd like more food history book reviews, check out the Book Review category of this blog. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

0 Comments

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. Thanks to everyone who joined me on Friday for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week we discussed the role of riots and boycotts in history and food history, touching primarily on the food boycotts and riots and high cost of living protests of 1916/1917 which occurred around the globe. We also talked about women's suffrage and farmerettes, midnight suppers, Frank Meier, inventor of the bees' knees cocktail and his role in WWII, poison candy and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, food and riots or protests, including the role of food and cooking in the Civil Rights movement, Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Little House Cookbook, L. M. Montgomery, requests for next week, and a brief introduction to the history of gelatin, beaten biscuits, and other formerly upper-crust foods which became inexpensive convenience foods. If you want to watch back episodes you can check them out on right here on the blog or I am hoping to upload full episodes to YouTube now that my channel is officially verified! Bees' Knees Cocktail (1936)In 1936 Frank Meier published "The Artistry of Mixing Drinks," a beautifully designed little bartender's guide based on his time as the head bartender at the Hotel Ritz Carlton's Cafe Parisian, which opened in 1921. Frank had purportedly trained at the Hoffman House in New York City before taking on his new role at the Ritz. He served as head bartender and host for over twenty years and even played a role in the French Resistance during WWII, when the Ritz became German headquarters. Meier was a well-known originator of cocktails, including the famous "Bees' Knees," which he invented sometime in the 1920s. It became popular in the United States during Prohibition, likely because the honey and lemon masked the taste of bathtub gin. Frank's original recipe reads: "In shaker: the juice of one-quarter Lemon, a teaspoon of Honey, one-half glass of Gin, shake well and serve." A more modern recipe might be: Juice of 1/4 lemon (or half a tablespoon) 1 or 2 teaspoons of honey 1 or 1 1/2 ounce gin Shake over ice and serve in a cocktail glass. One teaspoon of honey definitely wasn't enough for me - I couldn't taste the honey at all! Perhaps "a dollop" might be a better descriptor. Here are some resources on some of the topics we discussed tonight:

Next week we'll be discussing Easy Bake Ovens, Jello and aspic, foods of the 1950s and '60s, and all sorts of other fun stuff. See you then! If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed