|

During the Second World War, food preservation became a national mandate. I've featured canning-related propaganda posters before, but I thought now would be a good time to feature a few of the lesser-known posters. The above poster is from fairly late in the war. It reads "Grow More, Can More... In '44 - Get your canning supplies now! Jars, Caps and Rings." A special seal featuring a hand (presumably Uncle Sam's) holds a basket containing the words, "Food Fights for Freedom" with "Produce and Conserve" and "Share and Play Square" above. It features a rosy-cheeked young woman in an overtly feminized take on the Women's Land Army overalls, a straw hat tilted fashionably far back on her head, and wearing spotless white work gloves. With a hoe tucked in one elbow and a thumb in her overall strap, she gestures with her free hand at an enormous set of glossy clear glass canning jars, expertly filled with whole tomatoes, halved peaches, green beans, sliced red beets, and what might be whole apricots, yellow plums, or yellow cherries, it's tough to tell. The jars feature a variety of lids, including the new aluminum screw-tops, a glass-topped wire bail with a rubber seal, and a zinc screw top with a rubber seal, illustrating the range of canning technologies still in use. The poster is photorealistic and is probably a literal cut-and-paste of actual photographs - a new technique in an era still dominated by illustrations. It's not clear exactly when this poster was released, but it's likely it was early in the season. The poster exhorts the reader to "grow more" in addition to canning more in 1944, which seems to indicate a spring release, despite the prominence of the large glass canning jars. In addition, the poster warns to stock up on canning supplies now, instead of later in the season. When aluminum was short and factories that made glass were used to produce war materiel, it was easier to make smaller quantities over a longer period of time. By planning ahead, home gardeners and canners could also make sure they had enough supplies on hand to handle an increase in garden produce. Things were getting a bit desperate in 1944 - the war was not going well and the prospect of another long year of war was troubling to ordinary Americans. Rationing had ramped up fully in 1943, and as the war dragged on home canned foods took on more importance in everyday nutrition. For many, especially children, the war must have seemed unending. Little did they know that on June 6, 1944, the United States would launch Operation Overlord - also known as the invasion of Normandy - which would become known as D-Day. D-Day would turn the tide of the war in favor of the Allies, but it would still take another fifteen months for the war to end entirely. Until then, rationing continued and Americans were urged to grow and preserve as much food as they could to supplement their rations. The war finally ended in September of 1945, and by December, rationing of every food except sugar had ended. Foods canned in 1944 would have been important support for rations, but foods canned in 1945 would have been less crucial. One wonders how many home canned foods made it to the end of 1946? We may never know. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join now for as little as $1/month.

Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

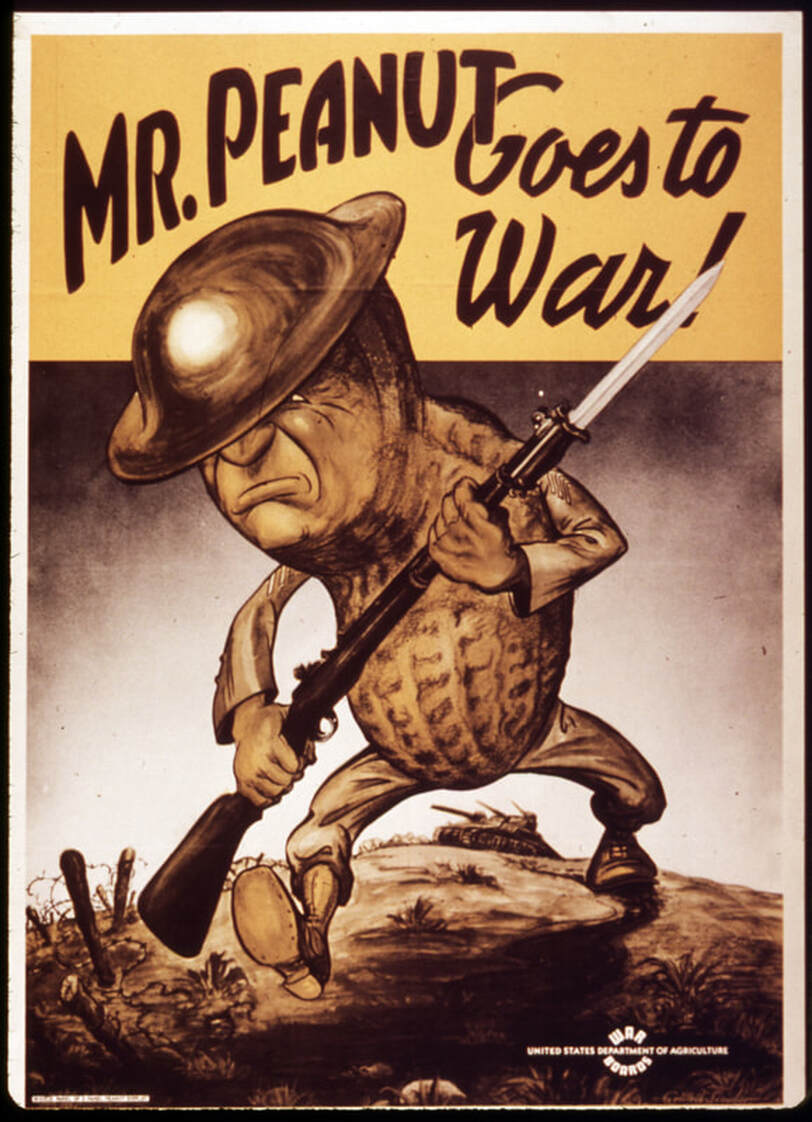

When you think of rationing in World War II, you may not think of peanuts, but they played an outsized role in acting as a substitute for a lot of otherwise tough-to-find foodstuffs, mainly other vegetable fats. When the United States entered the war in December, 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the dynamic of trade in the Pacific changed dramatically. The United States had come to rely on cocoanut oil from the then-American colonial territory of the Philippines and palm oil from Southeast Asia for everything from cooking and the production of foods like margarine to the manufacture of nitroglycerine and soap. Vegetable oils like coconut, palm, and cottonseed were considered cleaner and more sanitary than animal fats, which had previously been the primary ingredient in soap, shortening, and margarine. But when the Pacific Ocean became a theater of war, all but domestic vegetable oils were cut off. Cottonseed was still viable, but it was considered a byproduct of the cotton industry, not an product in and of itself, and therefore difficult to expand production. Soy was growing in importance, but in 1941 production was low. That left a distinctly American legume - the peanut. Peanuts are neither a pea nor a nut, although like peas they are a legume. Unlike peas, the seed pods grow underground, in tough papery shells. Native to the eastern Andes Mountains of South America, they were likely introduced to Europe by the Spanish. European colonizers then also introduced them to Africa and Southeast Asia. In West Africa, peanuts largely replaced a native groundnut in local diets. They were likely imported to North America by enslaved people from West Africa (where peanut production may have prolonged the slave trade). Peanuts became a staple crop in the American South largely as a foodstuff for enslaved people and livestock, but the privations of White middle and upper classes during the American Civil War expanded the consumption of peanuts to all levels of society. Union soldiers encountered peanuts during the war and liked the taste. The association of hot roasted peanuts with traveling circuses in the latter half of the 19th century and their use in candies like peanut brittle also helped improve their reputation. Peanuts are high in protein and fats, and were often used as a meat substitute by vegetarians in the late 19th century. Peanut loaf, peanut soup, and peanut breads were common suggestions, although grains and other legumes still held ultimate sway. George Washington Carver helped popularize peanuts as a crop in the early 20th century. Peanuts are legumes and thus fix nitrogen to the soil. With the cultivation of sweet potatoes, Carver saw peanuts as a way to restore soil depleted by decades of cotton farming, giving Black farmers a way to restore the health of their land while also providing nutritious food for their families and a viable cash crop. During the First World War, peanut production expanded as peanut oil was used to make munitions and peanuts were a recommended ration-friendly food. But it was consumer's love of the flavor and crunch of roasted peanuts that really drove post-war production. By the 1930s, the sale of peanuts had skyrocketed. No longer the niche boiled snack food of Southerners or ground into meal for livestock, peanuts were everywhere. Peanut butter and jelly (and peanut butter and mayonnaise) became popular sandwich fillings during the Great Depression. Roasted peanuts gave popcorn a run for its money at baseball games and other sporting events. Peanut-based candy bars like Baby Ruth and Snickers were skyrocketing in sales. And roasted, salted, shelled peanuts were replacing the more expensive salted almonds at dinner parties and weddings. Peanuts were even included as a "basic crop" in attempts by the federal government to address agricultural price control. They were included in the 1929 Agricultural Marketing Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, and an April, 1941 amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. Peanuts were included in farm loan support and programs to ensure farmers got a share of defense contracts. By the U.S. entry into World War II, most peanuts were being used in the production of peanut butter. And while Americans enjoyed them as a treat, their savory applications were ultimately less popular as an everyday food. But their use as source of high-quality oil was their main selling point during the Second World War. Peanut oil was the primary fuel in Rudolf Diesel's first engine, which debuted in 1900 at the Paris World's Fair. Its very high smoke point has made it a favorite of cooks around the world. During the Second World War peanut oil was used to produce margarine, used in salad dressings and as a butter and lard substitute in cooking and frying. But like other fats, its most important role was in the production of glycerin and nitroglycerine - a primary component in explosives. Which brings us to our imagery in the above propaganda poster. "Mr. Peanut Goes to War!" the poster cries. Produced by the United States Department of Agriculture, it features an anthropomorphized peanut in helmet and fatigues, carrying a rifle, bayonet fixed, marching determinedly across a battlefield, with a tank in the background. Likely aimed at farmers instead of ordinary households, Mr. Peanut of the USDA was nothing like the monocled, top-hatted suave character Planter's introduced in 1916. This Mr. Peanut was tough, determined to do his part, and aid in the war effort. The USDA expected farmers (including African American farmers) to do the same. Further Reading: Note: Amazon purchases from these links help support The Food Historian.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

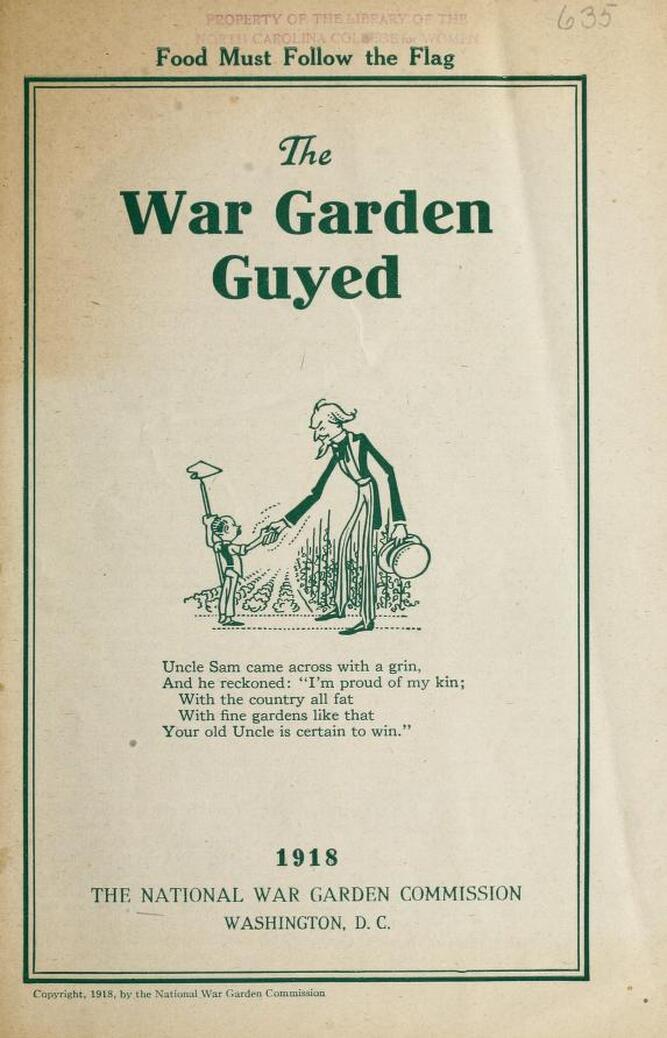

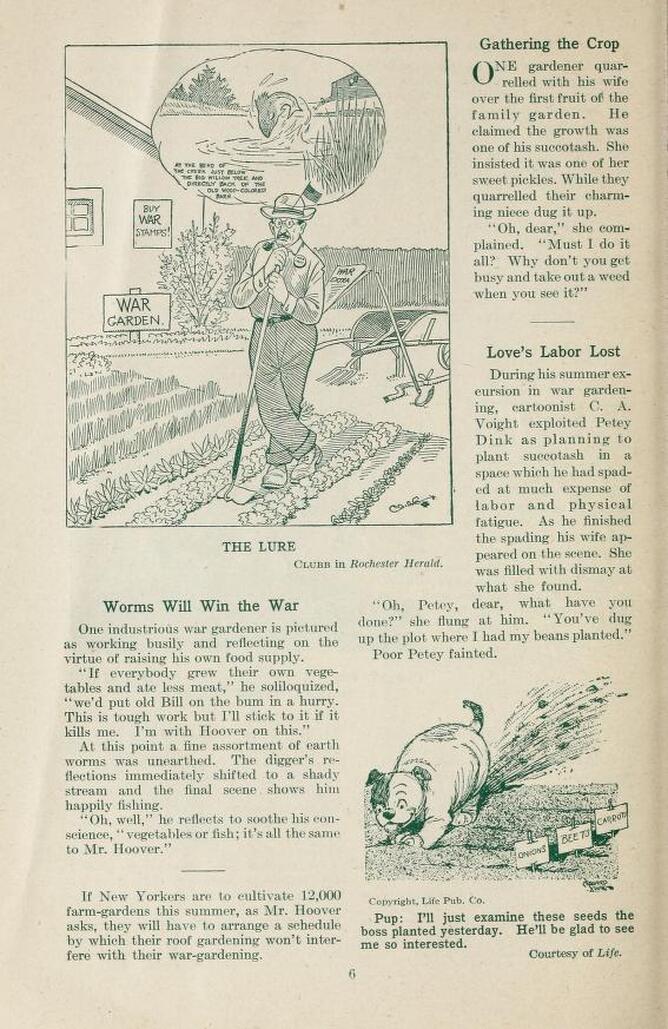

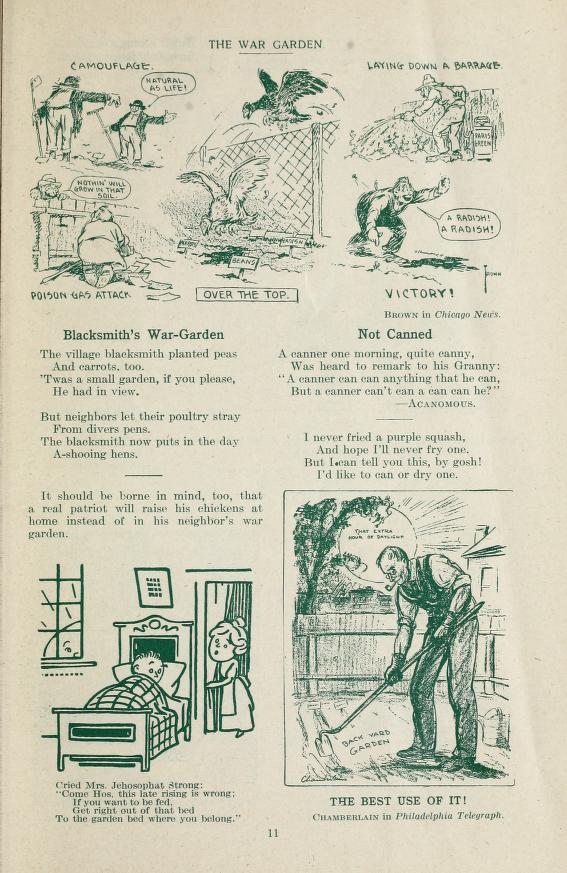

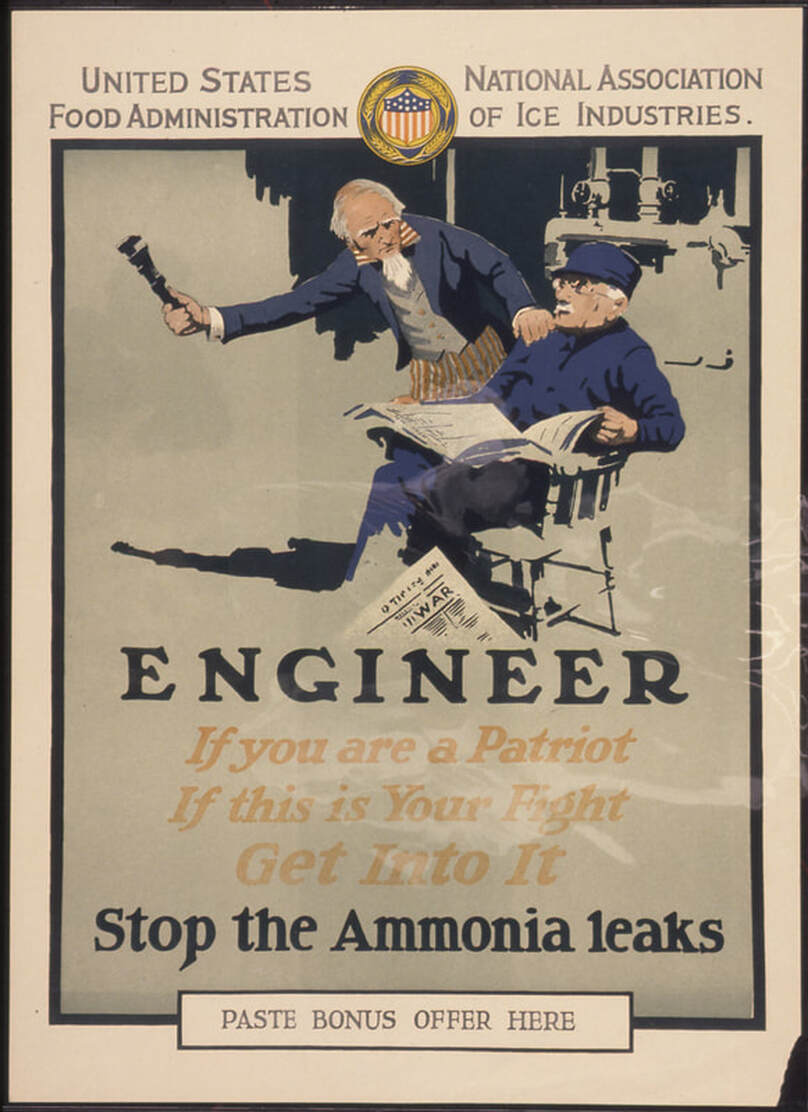

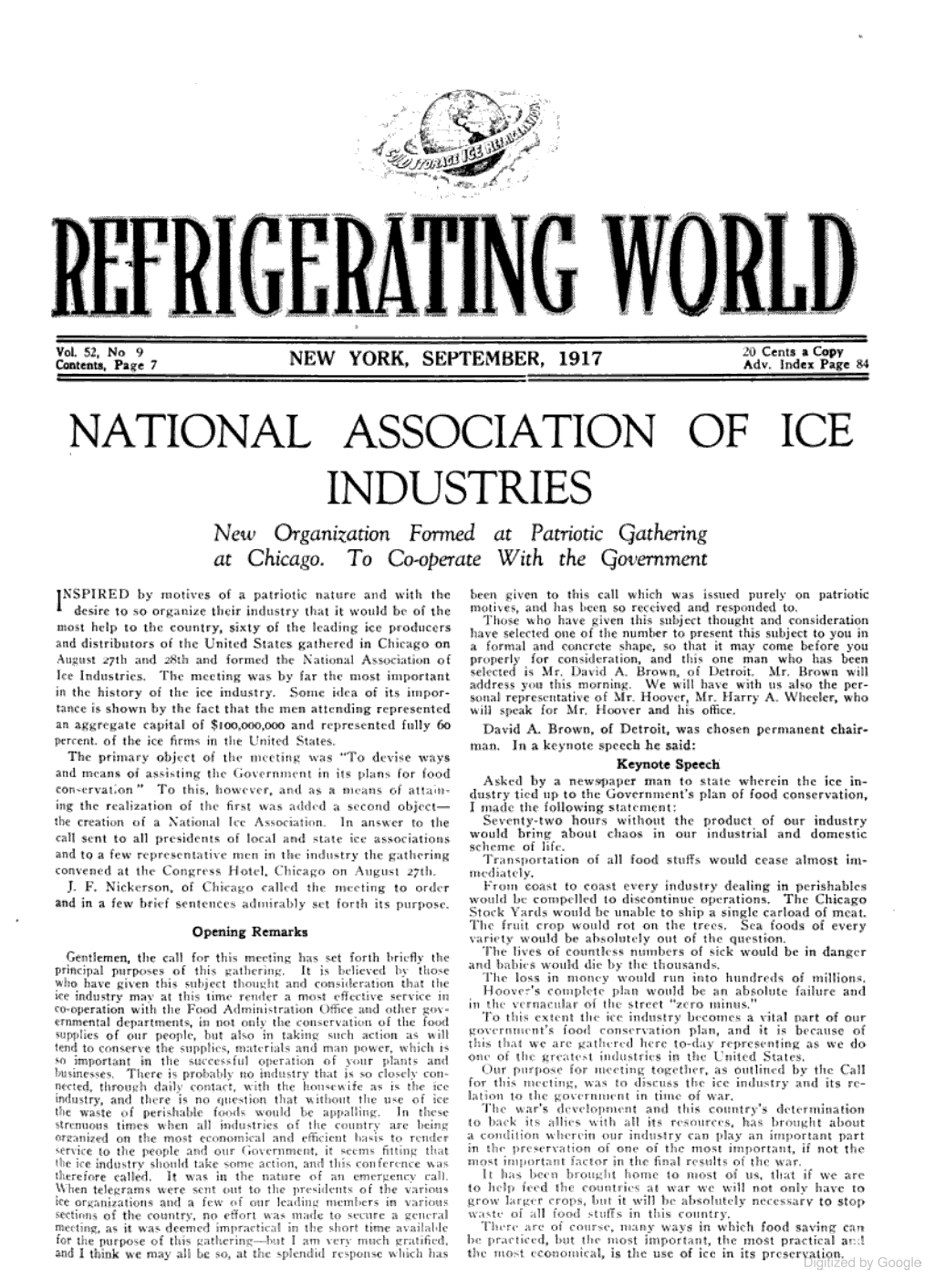

Although literal tons of snow have fallen across the United States in the past week or so, it's still beginning to feel like spring, which for many of us means our thoughts turn to gardening. If you know anything about World War II, you've probably heard of Victory Gardens. But did you know they got their start in the First World War? And the popularity of "war gardens" as they were initially called, is largely thanks to a man named Charles Lathrop Pack. Pack was the heir to a forestry and lumber fortune, and pumped lots of his own money into creating the National War Garden Commission, which promoted war gardening across the country, along with food preservation. They published a number of propaganda posters and instructional pamphlets. Today's World War Wednesday feature is another pamphlet, but its primary audience was not the general public, but rather newspaper and magazine publishers! Full of snippets of poetry, jokes, cartoons, and articles published by newspapers and magazines around the country, even the title was a bit of a joke. "The War Garden Guyed" is a play on the words "guide" and the verb "guy" which means to make fun of, or ridicule. So "The War Garden Guyed" is both a manual to war gardens and also a way to make fun of them. In the introduction, the National War Garden Commission (likely Charles Lathrop Pack himself), writes: "This publication treats of the lighter side of the war garden movement and the canning and drying campaign. Fortunately a national sense of humor makes it possible for the cartoonist and the humorist to weave their gentle laughter into the fabric of food emergency. That they have winged their shafts at the war gardener and the home canner serves only to emphasize the vital value of these activities." Each page of the "guyed" has at least one image and a few bits of either prose or poetry. The below page is one of my favorites. In the upper cartoon, an older man leans on his hoe in a very orderly war garden. His house in the background features a large "War Garden" sign and a poster saying "Buy War Stamps!" In his pocket is a folded newspaper with the headline "War Extra." But he is dreaming of a lake with jumping fish and the caption - indicating the location of the best fishing spot. The cartoon is called "The Lure" and demonstrates how people ordinarily would have been spending their summers. In the lower right hand corner, a roly poly little dog digs frantically in fresh soil. Little signs read "Onions, Beets, Carrots." The caption says "Pup: I'll just examine these seeds the boss planted yesterday. He'll be glad to see me so interested." Another article on the page is titled "Love's Labor Lost." It reads: "During his summer excursion in war gardening, cartoonist C. A. Voight exploited Petey Dink as planning to plant succotash in a space which had had spaded at much expense of labor and physical fatigue. As he finished the spading his wife appeared on the scene. She was filled with dismay at what she found. 'Oh Petey, dear, what have you done?' she flung at him. 'You've dug up the plot where I had my beans planted.' Poor Petey fainted." Many of the bits of doggerel and cartoons poked fun at inexperienced gardeners like Petey Dink. Pests, animals, digging up backyards and hauling water, the difficulty in telling weeds from seedlings, and finally the joy at the first crop. This page has a comic at the top that illustrates these trials and tribulations perfectly, through the lens of war. In the upper left hand corner, a sketch entitled "Camouflage" depicts a man who has just finished putting up a scarecrow who crows, "Natural as life!" as he poses exactly the same as his creation. Below, another called "Poison Gas Attack" depicts a neighbor leaning over the fence to comment "Nothin will grow in that soil" at a man kneeling in the dirt, a bowl of seed packets and a hoe on either side of him. The title implies that the neighbor is full of hot air and poison. The center scene, titled "Over the Top," shows a pair of chickens gleefully flying over a fence to attack a plot marked "Carrots," "Beans," and "Radishes." In the top right-hand corner, in a sketch titled "Laying Down a Barrage," a man with a pump cannister labeled "Paris Green" is spraying his plants. Paris Green was an arsenical pesticide. And finally, in one labeled "Victory!" a man gleefully points to a small seedling in an otherwise empty row and cries, "A radish! A radish!" In a bit of verse called "Not Canned" reads: A canner one morning, quite canny, Was heard to remark to his Granny: "A canner can can anything that he can, But a canner can't can a can can he?" And finally, apt for this past weekend's Daylight Savings Time "spring forward" is an evocative sketch depicts a man hoeing up his back yard garden while a large sun shines brightly and reads "That extra hour of daylight." The sketch is captioned, "The best use of it!" "The War Garden Guyed" has 32 pages of verse, doggerel, short articles, and cartoons. Charles Lathrop Pack was correct when he said the newspapers evoked "gentle laughter" as none of the satirical sheets actually discourage gardening. Indeed, most of the text is directly in line with the propaganda of the day promoting the development of household war gardens and the movement to "put up" produce through home canning and drying. Many of the cartoons directly connect to the war itself, comparing fighting pests to fighting Huns, pesticides to ammunition and "trench gas," and equating canning and food preservation efforts with vanquishing generals. What the booklet does do is poke fun at all of the hardships and difficulties first-time or inexperience gardeners would face. Stray chickens, cabbage worms and potato beetles, dogs and children, competing spouses, naysaying neighbors, post-vacation forests of weeds, and trying desperately to impress coworkers and neighbors with first efforts. War gardens were no easy task, and there were plenty of people who felt that they were a waste of good seed. But Pack and the National War Garden Commission persisted. They believed that inspiring ordinary people to participate in gardening would not only increase the food supply, but also free up railroads for transporting war materiel instead of extra food, get white collar workers some exercise and sunshine, and provide fresh foods in a time of war emergency. How successful the gardens of first-year gardeners were is certainly debatable. But in many ways, war gardens were more about participating than food. After the war, Pack rebranded his "war gardens" as "victory gardens," asking people to continue planting them even in 1919. The idea struck such a chord that when the Second World War rolled around two decades after the first had ended, "victory gardens" and home canning again became a clarion call for ordinary people to participate in the war on the home front. The full "War Garden Guyed" has been digitized and is available online at archive.org. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! You may be wondering, what on earth do ammonia and engineers have to do with food history? Well, ammonia was one of the primary ingredients in creating artificial ice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The poster above shows Uncle Sam brandishing a wrench, hand on the shoulder of an older engineer, who reclines in a chair reading the newspaper. One sheet of the newspaper has fallen to the floor, and we can make out "War" in the headline. In the background we can see the outlines of pipes and valves. The poster reads "ENGINEER - If you are a patriot, If this is your fight, Get Into It - Stop the Ammonia Leaks." The top of the poster indicates it was sponsored by both the United States Food Administration and the National Association of Ice Industries. Refrigeration was changing rapidly in the 1900s. Most of the country still refrigerated with "natural ice," or ice harvested in winter from freshwater sources like lakes and rivers. But "artificial ice," that is water frozen mechanically, was gaining ground. Artificial ice making factories had been around since the 1870s, but they were costly and inefficient, used primarily in warmer climes where shipping natural ice was too inefficient. The primary refrigerant in these factories was ammonia, which has explosive properties. In fact, ammonia is a primary component in making gunpowder and explosives, and obviously demand for its use went up exponentially when the U.S. joined the First World War in April of 1917. Ammonia cools through compression. Jonathan Reese in Before the Refrigerator: How We Used to Get Ice (Amazon affiliate link) explains the process: The compression refrigeration cycle depends on the compressor forcing a refrigerant around a system of coils. A refrigerant is any substance that can be used to draw heat away from an adjoining space, but some refrigerants worked much better than others. During the late nineteenth century, most American refrigerating machines used ammonia as their refrigerant. The main advantage of ammonia was that it was very efficient. In other words, it has a very low vaporizing temperature (or boiling point) at which it will turn from a liquid into a gas. This means that it required less energy to propel it through the cycle and remove heat from whatever space or substance that the operator needed to become cold. If ammonia leaked through the pipes of these early machines (which it was prone to do), under certain circumstances it could even explode, as the New York packing house example described above illustrates.¹⁰ Most American refrigerating equipment manufacturers didn’t realize that until ammonia compression refrigeration systems had become extremely popular.¹¹ Cold storage also increased in use during the First World War, and refrigerated railroad cars, which helped drive agricultural specialization in fruits and vegetables around the country (Georgia peaches, Florida oranges, Michigan cherries, New York apples, and California's salad bowl), depended on ice for refrigeration and cooling. Ice was the invisible ingredient in the nation's food system. The National Association of Ice Industries was founded in August, 1917 in Chicago, IL as ice harvesters, producers, and distributors gathered at a conference. Realizing the importance of the ice trade in food preservation and conservation, the association vowed to cooperate with the government as part of the war effort. The conference proceedings were reported in Refrigerating World, the industry's trade journal, in the September, 1917 issue. In addition to forming the National Association of Ice Industries on the second day of the conference, the attendees also discussed convincing farmers of the benefits of cold storage and encouraging them to construct ice houses on their farms, of convincing the public that using ice and refrigeration would reduce food waste and save money, and finally of reducing inefficiencies in delivery, including advocating for one delivery service making one delivery per day to prevent competing delivery companies from wasting manpower, horsepower, and ice. Wartime not only necessitated the conservation of ammonia, but also gave the natural ice industry a boost. Already in decline due to concerns about polluted waterways, the natural ice industry was encouraged to revive as another way to conserve ammonia and the fuel that powered the steam engines and electric motors that powered the refrigerating process. The revival would ultimately be short-lived. The end of the First World War all but ended the natural ice industry. As refrigerants became abundant again and energy prices came back down, the demand for artificial ice went up. The advent of electric home refrigerators in the 1920s ultimately signaled the end of the household ice box, and the deliveries that went with it. Read More: The Amazon affiliate links below help support The Food Historian

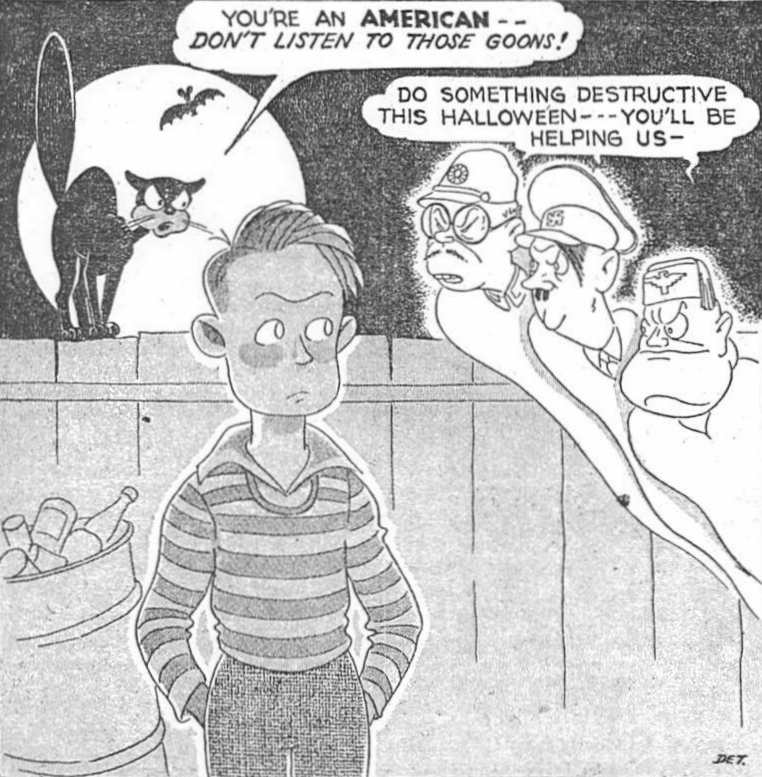

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month!  Cartoon published in the "San Diego Union," October 25, 1942. Ghosts of Emperor Hirohito of Japan, Adolph Hitler of Germany, and Benito Mussolini say in unison, "Do something destructive this Halloween - you'll be helping us -" to a teenaged boy in an alley. A black cat on the fence behind him says, "You're an AMERICAN - don't listen to those goons!" Trick or treating today is usually about young children, costumes, and lots of candy. In many communities, it's over by 8 or 9 pm. But historically, trick or treating was more about the tricks than the treats. Going door to door threatening tricks if treats were not offered instead is very old, but has deeper roots in association with Christmas than with Halloween. Despite the tradition's age, going door to door for treats on Halloween was not widely practiced in the United States until the 20th century. The pranks, however, were popular among teenaged boys. From the relatively harmless pranks like soaping car windows and placing furniture on porch roofs to the destructive ones like slashing tires, breaking windows, egging houses, and starting fires in the streets, pranks were common in communities across the country. The war changed all that. Halloween, 1942 was the first since the United States entered the war in December, 1941. Across the nation, newspapers published warnings to would-be prankers that destructive acts of the past would no longer be tolerated. This one, published on October 30, 1942 in The Corning Daily Observer in Corning, California, was typical of other messages other newspapers: "Hallowe'en Pranks Are Out For the Duration" "The destructive Hallowe'en pranks of breaking fences, stealing gates, deflating auto tires, ringing door bells to disturb sleepers, soaping windows, and all other forms of the removal or destruction of buildings or property are definitely out and forbidden on Hallowe'en night, according to word from Corning city officials. "Supplies are needed for national defense and are too scarce to permit misuse. "Word comes from Washington that individuals committing such offense shall be prosecuted as saboteurs and be treated accordingly. "Corning officials state that there will be no fooling about this matter this year and anyone contemplating 'having fun' will be treated with severely." The newspaper cartoon above, published in the San Francisco Union on October 25, 1942, illustrates just this sentiment. In it, the ghosts of Japanese Emperor Hirohito, German Chancellor Adolph Hitler, and Italian fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini egg on a young boy hanging out in a dark back alleyway. "Do something destructive this Halloween - - - You'll be helping us - " they tell him. On the high fence behind the boy stands a black cat, back arched in anger, silhouetted by a full moon. He says to the boy, "You're an American - - Don't listen to those goons!" Conflating Halloween pranks with sabotage and aiding the Axis powers was no joke. The November, 1942 newspapers feature stories of pranksters waking sleeping war workers, scaring their neighbors by setting off air raid bells, and causing car accidents by leaving debris in the roads. Several ended up in court, and some got buckshot wounds from angry homeowners for their efforts. Wartime propaganda like this was common - caricatures of the Axis leaders showed up frequently in newspapers, cartoons, and propaganda posters. For Halloween, they made convenient bogeymen. World War II was the beginning of the end of Halloween tricks. Although more innocuous pranks like egging houses and cars and toilet-papering trees and porches continued to be hallmarks of Halloween mischief, the days of fires in the streets, broken windows, and other real crimes were largely in the past. Communities that had previously celebrated Halloween with private parties at home, shifted to more public events like parades, community dances, and trick-or-treating geared toward small children getting treats rather than teenagers engaging in tricks. Further Reading If you'd like to learn more about Halloween during World War II, check out these additional resources:

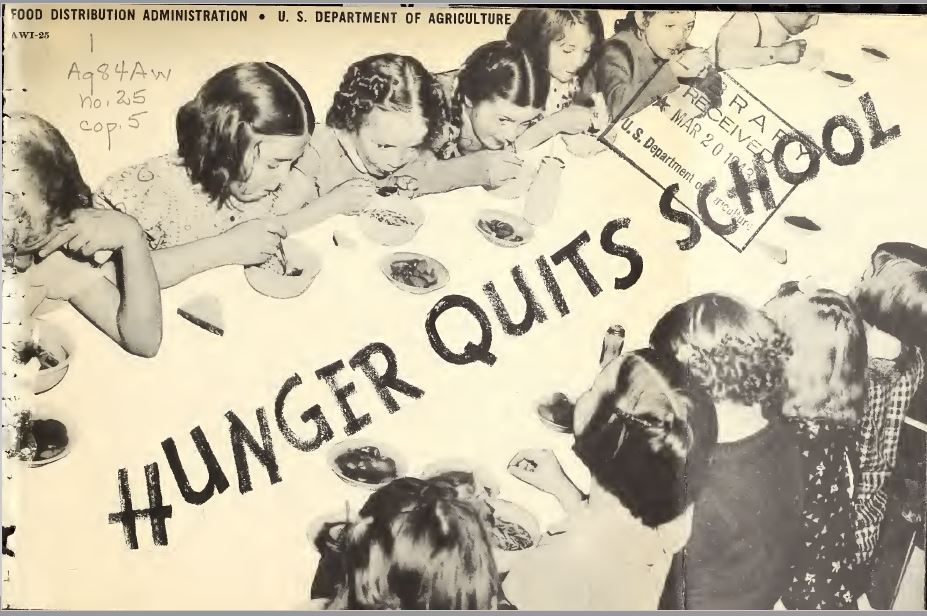

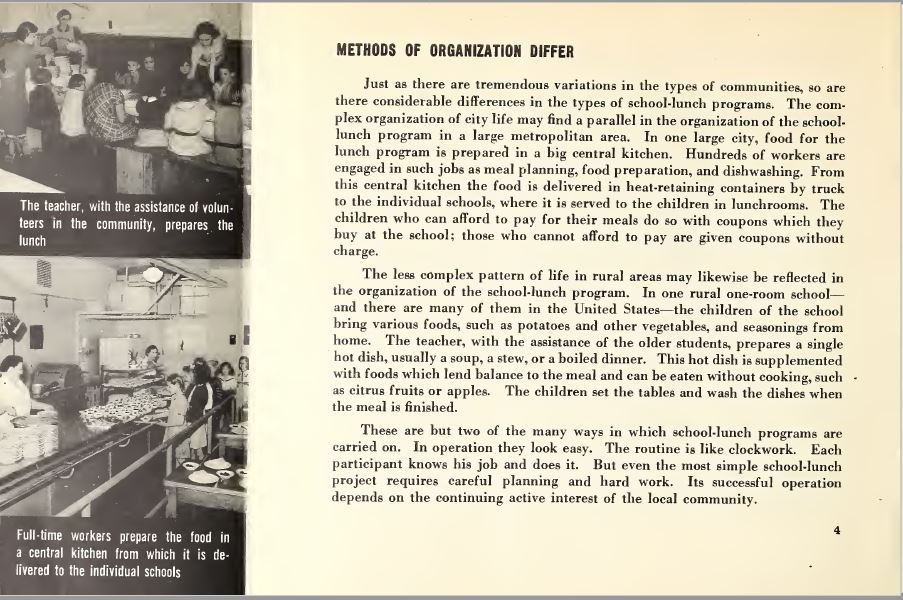

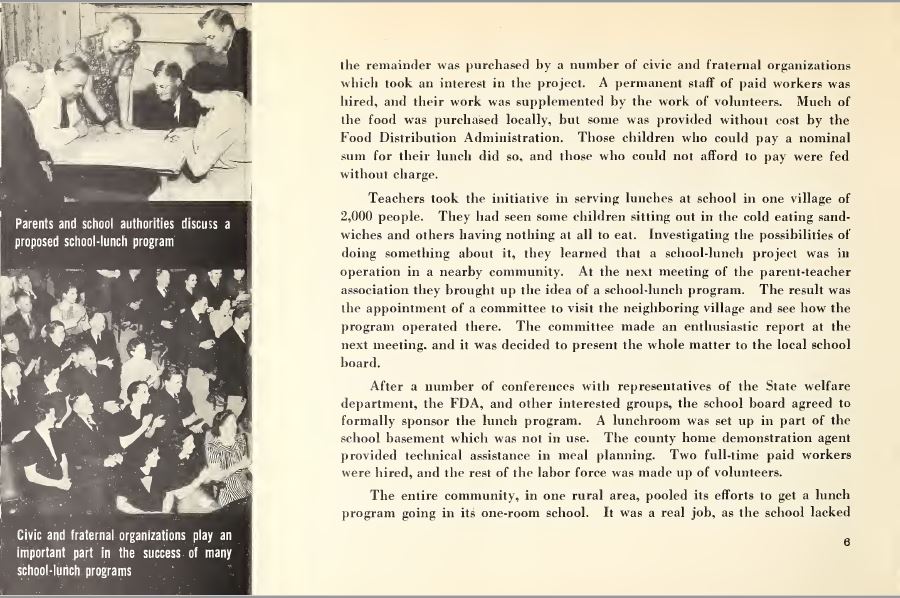

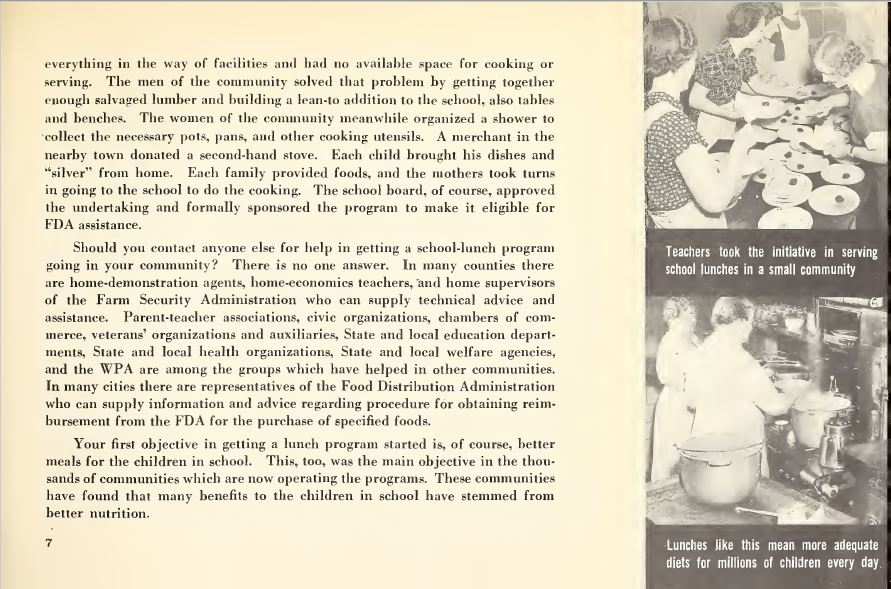

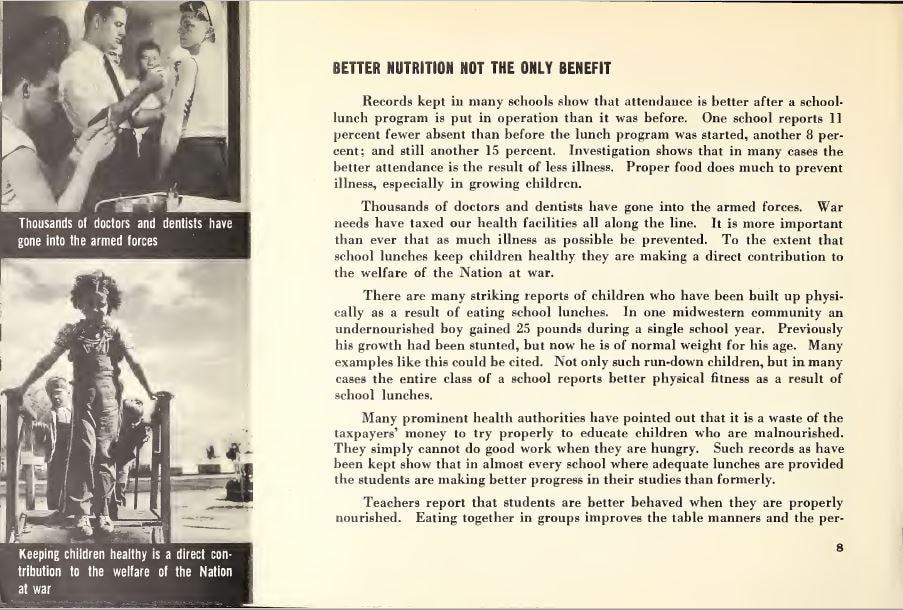

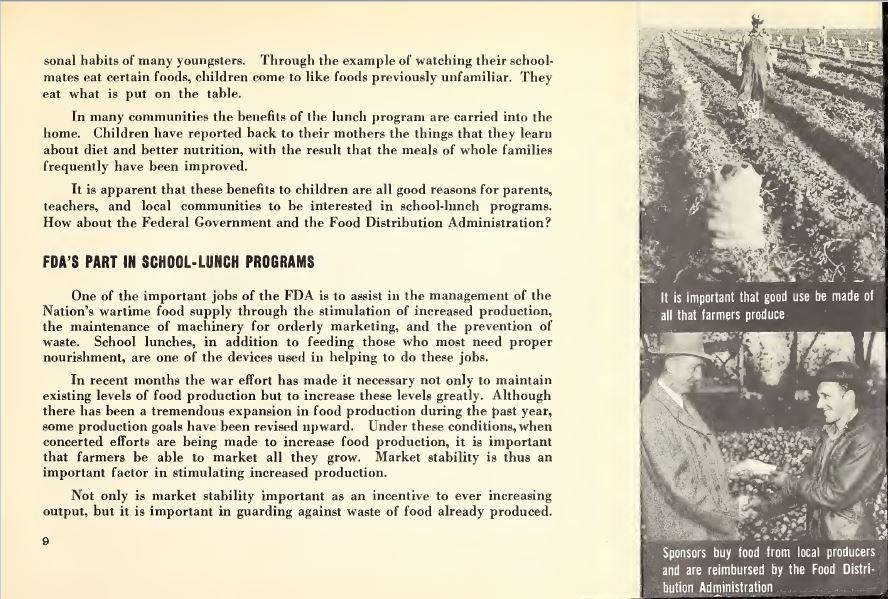

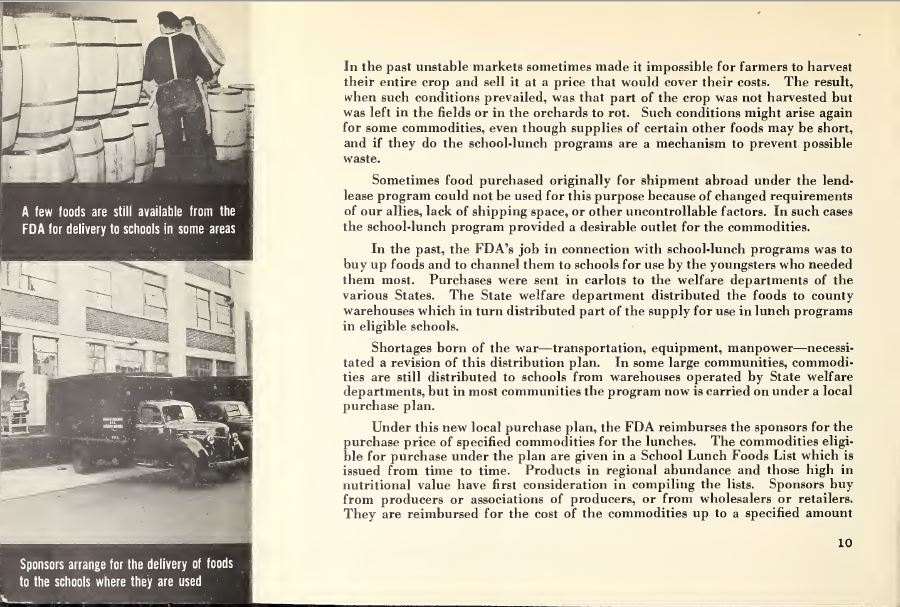

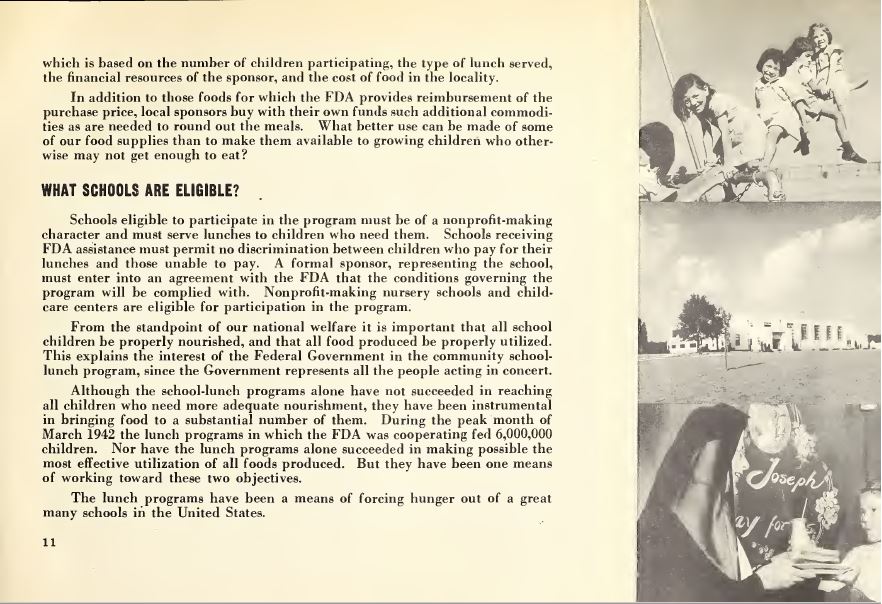

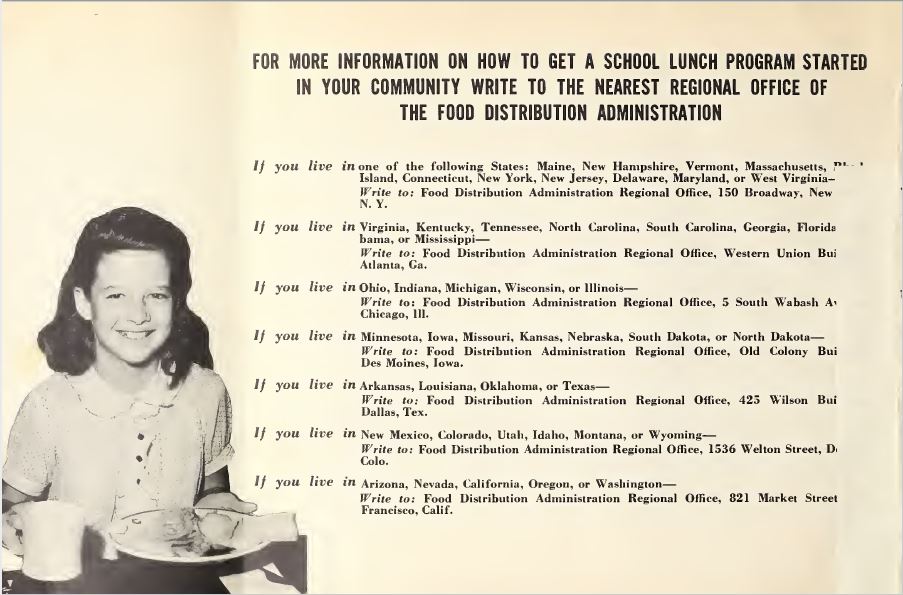

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! In 1943, the USDA published the informational booklet Hunger Quits School. On December 5, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the Food Distribution Administration, which oversaw, among other things, the school-lunch program. School lunch was influenced in part by the military draft. As many as a quarter of recruits were rejected for military service due to malnutrition. The panic around military readiness lead to many advancements in nutrition science and education of ordinary Americans about nutrition, including the development of the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations and yes, even school lunch. I've transcribed and shown the booklet in its entirety for your reading pleasure and edification. As you read you'll see how clearly school lunch programs were tied to military readiness even in the period, as well as how their execution differed in various communities. If you'd like to learn more about the history of school lunch, scroll to the bottom for reading recommendations. "Hunger has quit 93,000 schools throughout the United States where programs to provide noonday meals to students are operated by local communities in cooperation with the Food Distribution Administration. These programs are providing wholesome food to those who need it most - they are helping to build a healthy and physically fit population. Shortages of certain commodities cannot be permitted to impair the welfare of our future citizens. It is imperative that the youngsters who most need nourishing food get it in their school lunch. War adds to the urgency of the task. "A physically fit population and properly managed food supply are essential now more than ever before. Obviously, school-lunch programs are not substitutes for the courage of fighting men, for a fleet of airplanes, for guns, ships, tanks, or for the purchase of war bonds and stamps. Nevertheless, they are important in the Nation's War effort, since in modern total war the requirements for victory are indivisible." Images to left of text: Stylized black and white warship "Ships must transport food," stylized soldiers in a mess tent "Soldiers must eat," stylized workers in a factory with lunch room "Workers must eat," stylized woman typing and separate building with family in kitchen "Civilians must eat," stylized children sitting at table with knives and forks "Our children must eat." "WHY COMMUNITY SCHOOL-LUNCH PROGRAMS? "From the standpoint of the local community the reasons for operating lunch programs in the schools are immediate and easy to understand. Mothers and fathers, teachers and school administrators, doctors and health officers, and others in the community know the importance of having children eat properly. Since most children are away at school during lunch time for most of the year, the school lunch is an important part of the total diet of the individual. "Because parents, teachers, and others know the importance of proper food, that doesn't necessarily mean that all school children get the right kind of lunch or any lunch at all for that matter. In many cases, parents don't have enough money to put the right kinds of food in their children's lunch pails. In some cases - and this is increasingly true as more women go into war work - parents just don't have the time to put up the right kind of lunch for their children. In other cases, parents aren't well enough informed about nutrition to prepare an adequate lunch for their children. "All these and other factors have prompted local people to establish school-lunch programs as community enterprises. Programs are currently in operation to provide noonday meals to children in schools in every State and the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Thousands of persons - parents, teachers, volunteer workers, and well as paid workers - are giving their time and effort to carry on these projects, and millions of children are benefiting. "Although the Food Distribution Administration of the United States Department of Agriculture cooperated in school lunch programs in 93,000 schools during the 1941-42 school year by furnishing various foods without charge, the major responsibility for initiation of each program and for its successful operation is a community responsibility." Images to the right of text: Above, photo of young white boy outside a school eating a sandwich "The Cold Sandwich is no substitute." Below, photo of white children eating soup at a long table, caption continues ". . . For a Well-Balanced Hot Lunch." "METHODS OF ORGANIZATION DIFFER Just as there are tremendous variations in the types of communities, so are there considerable differences in the types of school-lunch programs. The complex organization of city life may find a parallel in the organization of the school lunch program in a large metropolitan area. In one large city, food for the lunch program is prepared in a big central kitchen. Hundreds of workers are engaged in such jobs as meal planning, food preparation, and dishwashing. From this central kitchen the food is delivered in heat-retaining containers by truck to the individual schools, where it is served to the children in lunchrooms. The children who can afford to pay for their meals do so with coupons which they buy at the school; those who cannot afford to pay are given coupons without charge. "The less complex pattern of life in rural areas may likewise be reflected in the organization of the school-lunch program. In one rural one-room school - and there are many of them in the United States - the children of the school bring various foods, such as potatoes and other vegetables, and seasonings from home. The teacher, with the assistance of the older students, prepares a single hot dish, usually a soup, a stew, or a boiled dinner. This hot dish is supplemented with foods which lend balance to the meal and can be eaten without cooking, such as citrus fruits or apples. The children set the tables and wash the dishes when the meal is finished. "These are but two of the many ways in which school-lunch programs are carried on. In operation they look easy. The routine is like clockwork. Each participant knows his job and does it. But even the most simple school-lunch project requires careful planning and hard work. Its successful operation depends on the continuing active interest of the local community." Images to left of text: Top, black and white photo of white adult women helping white students at lunch table, "The teacher, with the assistance of volunteers in the community, prepares the lunch." Bottom, black and white photo of open kitchen with white women cafeteria workers and line of white children, "Full-time workers prepare the food in a central kitchen from which it is delivered to the individual schools." "HOW TO GET STARTED IN YOUR COMMUNITY "Suppose the school in your community does not have a lunch program and you would like to see one in operation. How do you go about getting it started? "The first thing to keep in mind is that this is a job for your local people - yourself and your neighbors. Various agencies of the Government may lend you technical assistance, but the primary responsibility is yours. "If you have the interest and the willingness and the perseverance to follow through on a community lunch program, the thing to do is to get together with your neighbors, the parents of other school children, and see how much interest you can arouse and how much support you can get for the proposal. You will need much support if your plan is to be a success. "What you do next depends on what kind of community you live in. The procedure in a city of 100,000 population is different from that in a rural area. The steps to take are different in a city of 20,000 from those in a village of 2,000. But the procedure that has been followed in these different types of communities will give you an idea of what lies ahead in your effort to get started. "In one city of more than 100,000 population a group of mothers presented their proposal for a school-lunch program to the teachers and the principal of their neighborhood school. They were given a sympathetic hearing and arrangements were made to present the plan to the city superintendent of schools and the board of education. The meetings resulted in a survey to ascertain what facilities were available in the various schools for the operation of a lunch program on a city-wide basis, what additional facilities would have to be provided, and what would be needed in the way of financing. "The survey completed, plans were laid to put the school-lunch program into operation. Some of the needed facilities were provided from public funds, and" [. . . continued on next page] Image to right of text: Black and white photo of seated white adults as at a public meeting, "This is a job for local people . . . yourself and your neighbors." [continued from previous page] "the remainder was purchased by a number of civic and fraternal organizations which took an interest in the project. A permanent staff of paid workers was hired, and their work was supplemented by the work of volunteers. Much of the food was purchased locally, but some was provided without cost by the Food Distribution Administration. Those children who could pay a nominal sum for their lunch did so, and those who could not afford to pay were fed without charge. "Teachers took the initiative in serving lunches at school in one village of 2,000. They had seen some children sitting out in the cold eating sandwiches and others having nothing at all to eat. Investigating the possibilities of doing something about it, they learned that a school-lunch project was in operation in a nearby community. At the next meeting of the parent-teacher association they brought up the idea of a school-lunch program. The result was the appointment of a committee to visit the neighboring village and see how the program operated there. The committee made an enthusiastic report at the next meeting, and it was decided to present the whole matter to the local school board. "After a number of conferences with representatives of the State welfare department, the FDA, and other interested groups, the school board agreed to formally sponsor the lunch program. A lunchroom was set up in part of the school basement which was not in use. The county home demonstration agent provided technical assistance in meal planning. Two full-time paid workers were hired, and the rest of the labor forced was made up of volunteers. "The entire community, in one rural area, pooled its efforts to get a lunch program going in its one-room school. It was a real job, as the school lacked" [. . . continued on next page]. Images to left of text: Top photo, white adults gather around a table looking at papers "Parents and school authorities discuss a proposed school-lunch program." Bottom photo, white adults sit in auditorium, "Civic and fraternal organizations play an important part in the success of many school-lunch programs." [continued from previous page] "everything in the way of facilities and had no available space for cooking or serving. The men of the community solved the problem by getting together enough salvaged lumber and building a lean-to addition to the school, also tables and benches. The women of the community meanwhile organized a shower to collect the necessary pots, pans, and other cooking utensils. A merchant in the nearby town donated a second-hand stove. Each child brought his dishes and "silver" from home. Each family provided foods, and the mothers took turns going to the school to do the cooking. The school board, of course, approved the undertaking and formally sponsored the program to make it eligible for FDA assistance. "Should you contact anyone else for help in getting a school-lunch program going in your community? There is no one answer. In many counties there are home-demonstration agents, home-economics teachers, and home supervisors of the Farm Security Administration who can supply technical advice and assistance. Parent-teacher organizations, civic organizations, chambers of commerce, veterans' organizations and auxiliaries, State and local education departments, State and local health organizations, State and local welfare agencies, and the WPA are among the groups which have helped in other communities. In many cities there are representatives of the Food Distribution Administration who can supply information and advice regarding procedure for obtaining reimbursement from the FDA for the purchase of specified foods. "Your first objective in getting a school lunch program started is, of course, better meals for the children in school. This, too, was the main objective in the thousands of communities which are now operating the programs. These communities have found that many benefits to the children in school have stemmed from better nutrition." Images to right of text: top photo, white women stand next to table of plates of food, actively plating, "Teachers took the initiative in serving school lunches in a small community. Bottom photo, two white women stand in kitchen cooking, "Lunches like this mean more adequate diets for millions of children every day." "BETTER NUTRITION NOT THE ONLY BENEFIT "Records kept in many schools show that attendance is better after a school-lunch program is put in operation than it was before. One school reports 11 percent fewer absent than before the lunch program was started, another 8 percent; and still another 15 percent. Investigation shows that in many cases the better attendance is the result of less illness. Proper food does much to prevent illness, especially in growing children. "Thousands of doctors and dentists have gone into the armed forces. War needs have taxed our health facilities all along the line. It is more important than ever that as much illness as possible be prevented. To the extent that school lunches keep children healthy they are making a direct contribution to the welfare of the Nation at war. "There are many striking reports of children who have been built up physically as a result of eating school lunches. In one midwestern community an undernourished boy gained 25 pounds during a single school year. Many examples like this could be cited. Not only such run-down children, but in many cases the entire class of a school reports better physical fitness as a result of school lunches. "Many prominent health authorities have pointed out that it is a waste of the taxpayers' money to try properly to educate children who are malnourished. They simply cannot do good work when they are hungry. Such records as have been kept show that in almost every school where adequate lunches are provided the students are making better progress in their studies than formerly. "Teachers report that students are better behaved when they are properly nourished. Eating together in groups improves the table manners and the per-" [. . . continued on next page] Images to left of text: Top photo of white men administering vaccinations to other white men, "Thousands of doctors and dentists have gone into the armed forces." Bottom, young white children play on equipment outside, "Keeping children healthy is a direct contribution to the welfare of the Nation at war." [continued from previous page] "[per]sonal habits of many youngsters. Through the example of watching their schoolmates eat certain foods, children come to like foods previously unfamiliar. They eat what is put on the table. "In many communities the benefits of the lunch program are carried into the home. Children have reported back to their mothers the things that they learn about diet and better nutrition, with the result that the meals of whole families frequently have improved. "It is apparent that these benefits to children are all good reasons for parents, teachers, and local communities to be interested in school-lunch programs. How about the Federal Government and the Food Distribution Administration? "FDA'S PART IN SCHOOL-LUNCH PROGRAMS "One of the important jobs of the FDA is to assist in the management of the Nation's wartime food supply through the stimulation of increased production, the maintenance of machinery for orderly marketing, and the prevention of waste. School lunches, in addition to feeding those who most need proper nourishment, are one of the devices used in helping to do these jobs. "In recent months the war effort has made it necessary not only to maintain existing levels of food production but to increase these levels greatly. Although there has been a tremendous expansion in food production during the past year, some production goals have been revised upward. Under these conditions, when concerted efforts are being made to increase food production, it is important that farmers be able to market all they grow. Market stability is thus an important factor in stimulating increased production. "Not only is market stability important as an incentive to ever increasing output, but it is important in guarding against waste of food already produced." Images to right of text: top, a white farmer stands in the furrows of a field with sacks of potatoes, "It is important that good use be made of all that farmers produce." Bottom, two white men shake hands outdoors, "Sponsors buy from local producers and are reimbursed by the Food Distribution Administration." "In the past unstable markets sometimes made it impossible for farmers to harvest their entire crop and sell it at a price that would cover their costs. The result, when such conditions prevailed, was that part of the crop was not harvested but was left in the fields or in the orchards to rot. Such conditions might arise again for some commodities, even though supplies of certain other foods may be short, and if they do the school-lunch programs are a mechanism to prevent possible waste. "Sometimes food purchased originally for shipment abroad under the lend-lease program could not be used for this purpose because of changed requirements of our allies, lack of shipping space, or other uncontrollable factors. In such cases the school-lunch program provided a desirable outlet for the commodities. "In the past, the FDA's job in connection with school-lunch programs was to buy up foods and to channel them to schools for use by the youngsters who needed them most. Purchases were sent in carlots to the welfare departments of the various States. The State welfare department distributed foods to county warehouses which in turn distributed part of the supply for use in lunch programs in eligible schools. "Shortages born of the war - transportation, equipment, manpower - necessitated a revision of this distribution plan. In some large communities, commodities are still distributed to schools from warehouses operated by State welfare departments, but in most communities the program is now carried on under a local purchase plan. "Under this new local purchase plan, the FDA reimburses the sponsors for the purchase price of specified commodities for the lunches. The commodities eligible for purchase under the plan are given in a School Lunch Foods List which is issued from time to time. Products in regional abundance and those high in nutritional value have first consideration in compiling the lists. Sponsors buy from producers or associations of producers, or from wholesalers or retailers. They are reimbursed for the cost of the commodities up to a specified amount" [. . . continued on next page]. Images to left of text: top, two men load stack barrels, "A few foods are still available from the FDA for delivery to schools in some areas." Bottom, box trucks lined up outside a building as a man loads a box, "Sponsors arrange for the delivery of foods to the schools where they are used." [continued from previous page . . .] "which is based on the number of children participating, the type of lunch served, the financial resources of the sponsor, and the cost of food in the locality. "In addition to those foods for which the FDA provides reimbursement of the purchase price, local sponsors buy with their own funds such additional commodities as are needed to round out the meals. What better use can be made of some of our food supplies than to make them available to growing children who otherwise may not get enough to eat? "WHAT SCHOOLS ARE ELIGIBLE? "Schools eligible to participate in the program must be of a nonprofit-making character and must serve lunches to children who need them. Schools receiving FDA assistance must permit no discrimination between children who pay for their lunches and those unable to pay. A formal sponsor, representing the school, must enter into an agreement with the FDA that the conditions governing the program will be complied with. Nonprofit-making nursery schools and child-care centers are eligible for participation in the program. "From the standpoint of our national welfare it is important that all school children be properly nourished, and that all food produced be properly utilized. This explains the interest of the Federal Government in the community school-lunch program, since the Government represents all the people acting in concert. "Although the school-lunch programs alone have not succeeded in reaching all children who need more adequate nourishment, they have been instrumental in bringing food to a substantial number of them. During the peak month of March 1942 the lunch programs in which the FDA was cooperating fed 6,000,000 children. Nor have the lunch programs alone succeeded in making possible the most effective utilization of all foods produced. But they have been one means of working toward these two objectives. "The lunch programs have been a means of forcing hunger out of a great many schools in the United States." Images to right of text: Top: young white girls at play on a see-saw. Middle: a school building. Bottom: a white nun gives a sandwich and bottle of milk to a young white boy. "FOR MORE INFORMATION ON HOW TO GET A SCHOOL LUNCH PROGRAM STARTED IN YOUR COMMUNITY WRITE TO THE NEAREST REGIONAL OFFICE OF THE FOOD DISTRIBUTION ADMINISTRATION "If you live in one of the following States: Main, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, or West Virginia - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 150 Broadway, New York, N.Y. "If you live in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, or Mississippi - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, Western Union Building, Atlanta, Ga. "If you live in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, or Illinois - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 5 South Wabash Ave., Chicago, Ill. "If you live in Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, or North Dakota - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, Old Colony Building, Des Moines, Iowa. "If you live in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, or Texas - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 425 Wilson Building, Dallas, Tex. "If you live in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Montana, or Wyoming - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 1536 Welton Street, Denver, Colo. "If you live in Arizona, Nevada, California, Oregon, or Washington - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 821 Market Street, San Francisco, Calif." And that is the end of the transcription! What did you think? Were there any surprises in there for you? I had known for a long time that the school lunch program was a way to use up agricultural surpluses AFTER the war, but hadn't realized that using up wartime surpluses was a factor since the beginning. I also liked the emphasis on treating children who couldn't afford to pay no differently than those who could. FURTHER READING: If you'd like to learn more about the history of school lunch, check out these additional resources. (Purchases made from Amazon links help support The Food Historian):

Happy reading! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

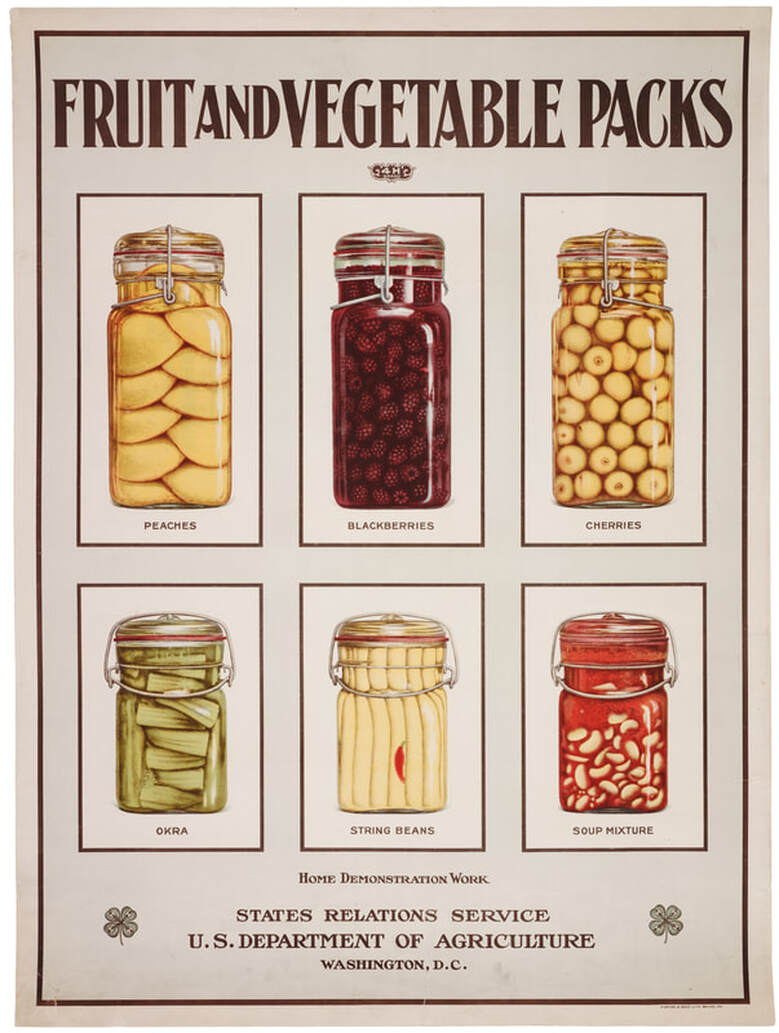

Home canning was promoted as essential to the war effort in both World Wars, but the First World War introduced ordinary Americans to a lot of research on the effectiveness and science of home canning. Although safe canning was still in its infancy (water bath canning low-acid vegetables was still sometimes recommended by home economists at this time, which we now know is not safe), approaching it with a scientific method was new to most Americans. This particular poster's purpose is unclear. Perhaps it was meant to demonstrate the best method of fitting fruits and vegetables into the jars. It is certainly beautiful. The unknown artist illustrated the clear glass wire bail quart and pint jars beautifully. Three quart jars are across the top containing perfectly layered halves of peaches, whole blackberries, and white Queen Anne cherries. Three pint jars across the bottom contain trimmed okra stacked vertically and horizontally, yellow wax beans (labeled "string beans"), which may have been pickled as a tiny red chile pepper can be seen near the bottom of the jar, and "soup mixture" containing white navy or cannellini beans and a red broth that likely contains tomatoes. Wire bail jars work by using rubber gaskets in between the glass jar and a glass lid to get the seal, held in place by tight wire clamps. Although beautiful, they are not recommended today for safe canning. They do, however, make effective and beautiful storage vessels for dry goods like flour, dried beans, spices, dried fruit, etc. (I recommend storing nuts in the freezer to prolong freshness.) Glass wire bail jars were common in the 1910s for home canning and became particularly important for the war effort as aluminum and tin became scarce due to their use in commercial canning and in wartime manufacturing. The poster interestingly includes vegetables in wire bail jars and even bean soup, which is not generally recommended to be canned with the water bath method. If the beans were pickled, they could be safely water-bath canned, but other low-acid vegetables like okra (unless also pickled) need to be pressure-canned to prevent the growth of botulism, a deadly toxin that can survive boiling temperatures. Although pressure canners existed during WWI, they were not in widespread use as they required the purchase of specialized equipment. Community canning kitchens were developed in large part to help housewives share the cost (and use) of more expensive equipment like pressure canners, steam canners, etc. This poster is from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and is labeled "Home Demonstration Work," which indicates it may have been used by home demonstration agents, or trained home economists hired by the USDA, cooperative extension offices, or local Farm Bureaus to train housewives in best practices for home management, including food preparation and preservation. Home demonstration work was in its infancy during World War I, and expanded greatly after the war. What do you think the purpose of this poster is? Share in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

This is one of the more famous food-related posters of the First World War. Created by famous illustrator and artist James Montgomery Flagg, "Sow the Seeds of Victory," and its sister poster (below) "Will you have a part in Victory?" were both produced by the National War Garden Commission, headed by Charles Lathrop Pack. The bottom of each poster reads "Every Garden a Munition Plant" with instructions in the lower right-hand corners reading "Write to the National War Garden Commission - Washington, D.C. for free books on gardening, canning, & drying." The posters both feature the same image - the United States embodied as Columbia, striding boldly, sandaled feet marching through a freshly plowed field, and broadcasting seed from a round basket. Columbia wears her Classical-style dress in the colors of the American flag - red, white, and blue - and wears a Phyrgian cap on her head, a symbol of freedom and liberty. The poster implies that by planting gardens, ordinary Americans could "Sow the seeds of Victory" and "plant and raise your own vegetables" - helping the war effort both literally and symbolically. Although "Every Garden a Munitions Plant" is a bit on the nose, the martial language helped reinforce the importance of growing vegetables at home, rather than consuming fuel and war materiel by purchasing vegetables grown far away, or canned commercially. The phrasing of the first poster is more in line with the sentiment of the image, and was likely the first produced. "Will you have a part in Victory" implies that the viewers may have already seen the first poster and understand its original intent. The Library of Congress estimates that these posters were produced in 1918, which is entirely possible, but the National War Garden Commission had instructional booklets on gardening, canning, and drying all published in 1917. Given that the NWGC was one of the first organizations to advocate for war gardens, even before the outbreak of war, so it is possible these are from 1917. Ironically, James Montgomery Flagg helped hasten the demise of Columbia as a symbol of the United States. His depiction of Uncle Sam, first featured on the July 6, 1916 cover of Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper asking "What are YOU doing for Preparedness?" - he later repurposed the image, inspired by Britain's Lord Kitchener, into the infamous "I Want YOU" Army recruitment poster, which was so effective it was recycled for the Second World War. By the 1930s, Uncle Sam (and his feminine counterpart, Aunt Sammy) had completely superseded Columbia as a symbol of the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! We've all had those days. Days where we forgot to bring lunch to work and can't get away to buy it, or when we bring a sad, cobbled-together lunch, or when we pick up fast food or something with empty calories. For many of us, a slow-moving afternoon or the distraction of a rumbling stomach isn't the end of the world. But during the Second World War, people didn't have the luxury of distraction of fatigue. This bold propaganda poster from c. 1943 features a yawning male worker leaning on the surface of what appears to be a stamping or hammering machine. He says, "Ho hum," feet crossed, leaning on his elbows, as a heavy block of metal descends toward his head. The poster reads, "Avoid fatigue! Eat a lunch that packs a punch!" During WWII, the United States engaged in total war. That meant that nearly every aspect of American society shifted toward the war effort. Nowhere was this more clear than in the everyday work of people in manufacturing. Men who weren't drafted for the war or working on farms often worked in factory settings. Factories that previously made machinery for consumer use - automobiles, refrigerators, washing machines, etc. - now found themselves manufacturing warplanes and Army jeeps and munitions. Factories worked on round-the-clock schedules, with three shifts a day. Some people worked much longer than 8 hours at a time. Although great strides had been made in ergonomics in factory work during the 1940s, the pressure of keeping up with military contracts and quotas was great. People often got too little sleep, and rationing made food supplies tight. During the war the U.S. federal government issued the Basic 7 - the first national nutrition guidelines ever issued. Based around the idea of balancing vitamin intake with protein, carbohydrates, and fats, the Basic 7 helped ordinary Americans better understand nutrition. Which is exactly what this poster is alluding to. "Eat a lunch that packs a punch" was a slogan also showed up in other posters, and alluded to calcium to keep bones strong, protein to build muscles, and Vitamin A to improve eyesight, among others. But this poster focuses on fatigue, which was a very real threat to the war machine. Tired workers made mistakes, hurt themselves, and could hurt or kill others. Operating flat out didn't leave room for mistakes, and a labor shortage thanks to the draft made skilled workers difficult to replace. Unbalanced meals, or not enough to eat, did not give war workers the energy they needed to perform at the highest levels at all times. The pressure of wartime work must have seemed unbearable at times. And with women increasingly joining the workforce and/or managing victory gardens and food preservation at home, not to mention coping with rationing, the idea of packing a large and nutritionally balanced lunch must have seemed like a lot of extra work for people. But while cafeterias were sometimes available, most people in factory work still packed their lunches. And while working at high speeds with dangerous equipment, it was worth it to make sure you weren't going to be too tired to do your job. There was no room for slacking off at work during the war, and getting proper nutrition to keep in peak physical health was so important the federal government spent a great deal of money advertising basic nutrition concepts (along with lots of posters about workplace safety) to ordinary Americans. Total war meant total commitment, total effort, and total focus. Staying healthy and well-fed was all part of total war. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

I am an unabashed fan of cottage cheese. I don't know when I first realized how delicious it is. Growing up, it always seemed some rubbery gross thing old ladies on a diet ate. Probably because the cottage cheese I tasted was likely skimmed milk cottage cheese and probably not very good quality. I certainly didn't think serving it with fruit or jam was a good idea, as was often touted by advertisements.

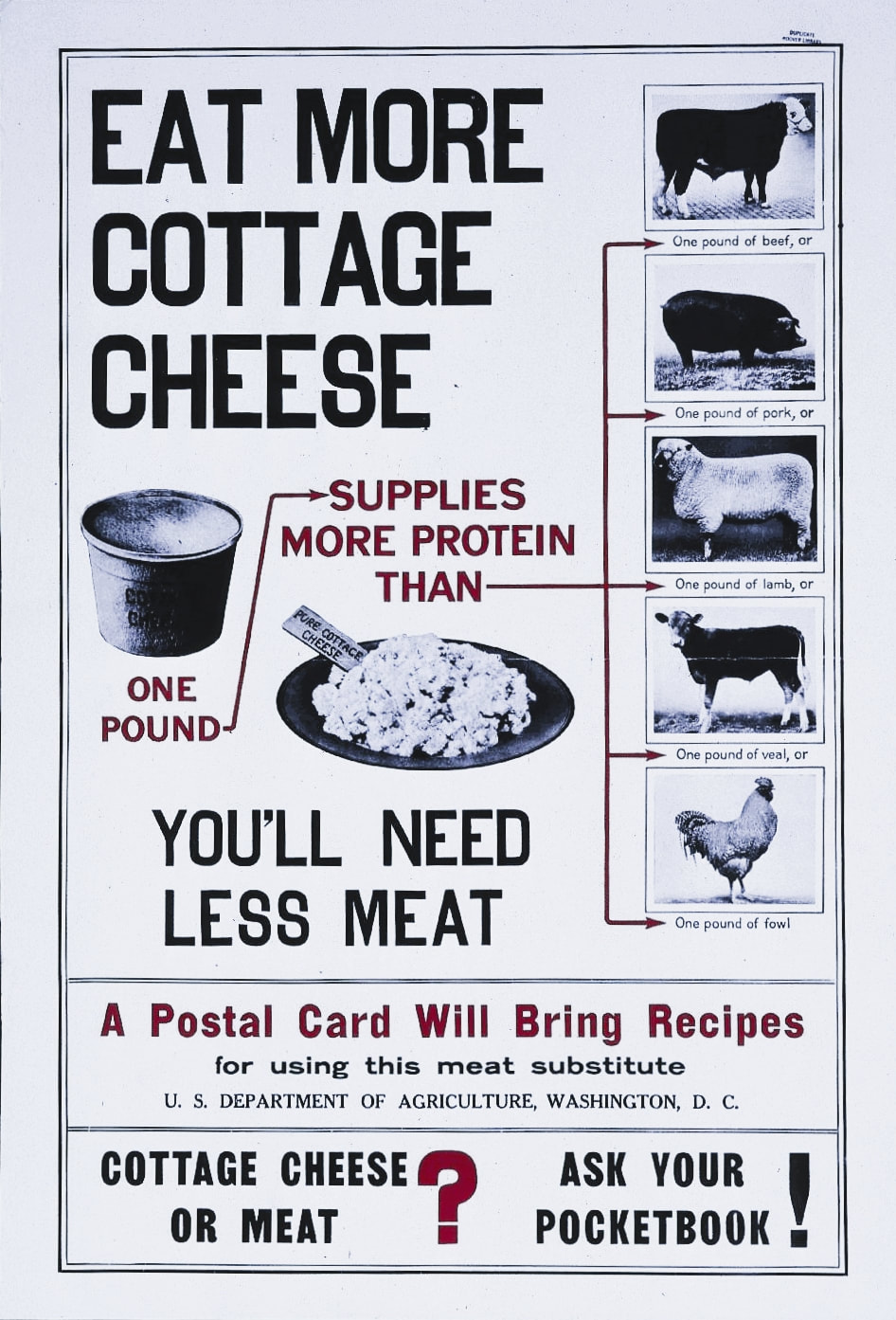

These days, cottage cheese has largely been superseded by yogurt, as NPR discussed in 2015, but I'm not sure that's a good thing. Cottage cheese is a very old style of fresh cheeses - a family that also encompasses ricotta, mascarpone, cream cheese, feta, mozzarella, goat and other un-aged cheeses that spoil rather quickly compared to their older cousins. But while all those other cheeses get their praises sung, cottage cheese gets short shrift (although not as short as farmer cheese, pot cheese, and dry cottage cheese, which are even harder to find). This propaganda poster from World War I exhorts Americans to "Eat More Cottage Cheese" and "You'll Need Less Meat" - comparing the protein in a pound of cottage cheese favorably to a pound of beef, lamb, pork, veal, and chicken. The First World War saw a dairy surplus, especially in 1918 as dairy farmers across the country fought for better fluid milk prices as cheese and evaporated/condensed milk stores overflowed and feed and labor prices went up. Food preservationists encouraged people to eat more dairy products, especially in the spring of 1918 when a huge milk surplus going into spring dairy season boded ill for the farmers and fair prices. Cottage cheese was touted as a meat substitute to kill two birds with one stone - it ate up some of the dairy surplus while also allowing people to eat less meat. As the poster suggests, cottage cheese was also far cheaper than meat, and still is today, although the gap has closed somewhat. The current national average price for a pound of ground beef is $5.41, and in April, 2022 the average price of a pound of boneless chicken breast was over $4, the highest in 15 years. A pound of cottage cheese has held pretty much steady between $2 and $4/pound, depending on the brand. My local grocery store brand, which is quite good, has 24 oz. (1.5 pound) containers available for just over $3, and often $2.50 or less on sale. Cottage cheese was also touted as a substitute during World War II, and post-war skimmed milk cottage cheese was promoted as a high-protein diet food, which is perhaps why so many of the latter generations disdained it.

A number of cookbooks and recipe pamphlets promoting cottage cheese use were published during World War I, including the above 100 Money-Saving Cottage Cheese Recipes published in 1918 by the Gridley Dairy Company and containing recipes like "Liberty Loaf," "Cottage Cheese Relish," "Cheese Pancakes," and over a dozen recipes for "Cottage Cheese Pie," plus cheesecakes!

Much of the advertisement of cottage cheese tended toward the sweet, like this hilariously 1950s advertisement from Borden, which features cottage cheese with jam, with maple syrup, and with fruit in a salad:

But most of my favorite recipes for cottage cheese treat it like the savory cheese it is. It's great in dips for raw veggies, as a topping for roasted vegetables, in savory salads, and yes, as a substitute for meat in fried foods. I even use farmer cheese (drained cottage cheese) in my favorite pastry crust recipe, which I use to make everything from cookies and apple butter bars to Cornish pasties and lentils Wellington.

Frankly, most Progressive Era reformers would have been better off asking Eastern European immigrants for the best ways to use cottage cheese, as it features prominently in Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, and Georgian cuisines. The USDA did a little better with their accompanying pamphlet on cottage cheese cookery:

Cottage Cheese Dishes: Wholesome, Economical, Delicious was published in 1918 by the USDA and contains slightly more sensible, savory uses for cottage cheese, including in salad dressings, scrambled eggs with cottage cheese, potato croquettes, and a lovely-sounding cold weather dish they call "Cottage Cheese Roll," which is cottage cheese mixed with cooked rice or breadcrumbs, seasoned well, and mixed with chopped vegetables, olives or pickles, leftover cold meats, canned salmon, etc. and formed into a roll which is then sliced and served on a bed of shredded lettuce. A suggested "Hot Weather Supper" is "cottage cheese roll made with rice and leftover salmon, served on a bed of lettuce leaves, with mayonnaise dressing; sliced tomatoes, oatmeal bread with nuts, whey lemonade, crisp fifty-fifty raisin cookies." The menu hits all the World War I food spots with a meat substitute (no, salmon wasn't considered "meat"), using up leftovers, using cottage cheese, using wheatless bread with protein-giving nuts, waste-less whey lemonade, and inexpensive and likely low- or no-sugar raisin cookies for dessert. How's that for conforming to rationing directives!

It also includes directions for making cottage cheese (which is incredibly easy to do at home - you just need a lot of milk, heat, and patience) and more importantly in my mind, some recipes for using up the leftover whey, including the aforementioned whey lemonade! How do you like to eat your cottage cheese?

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed