|

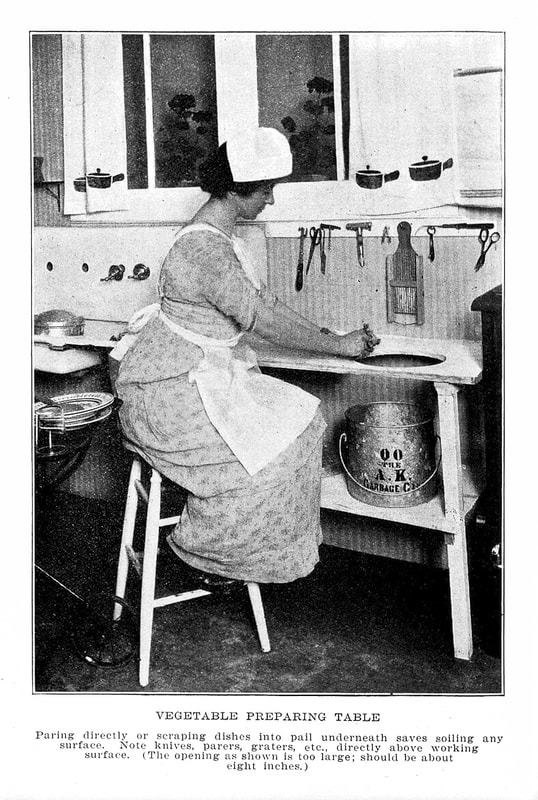

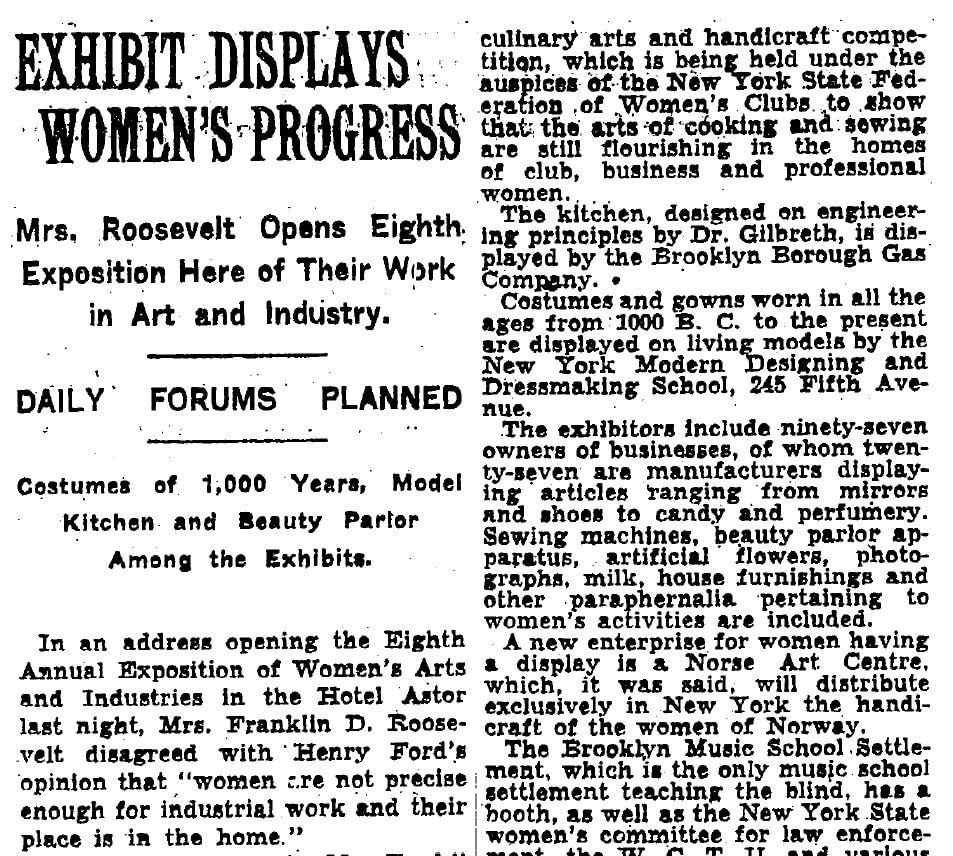

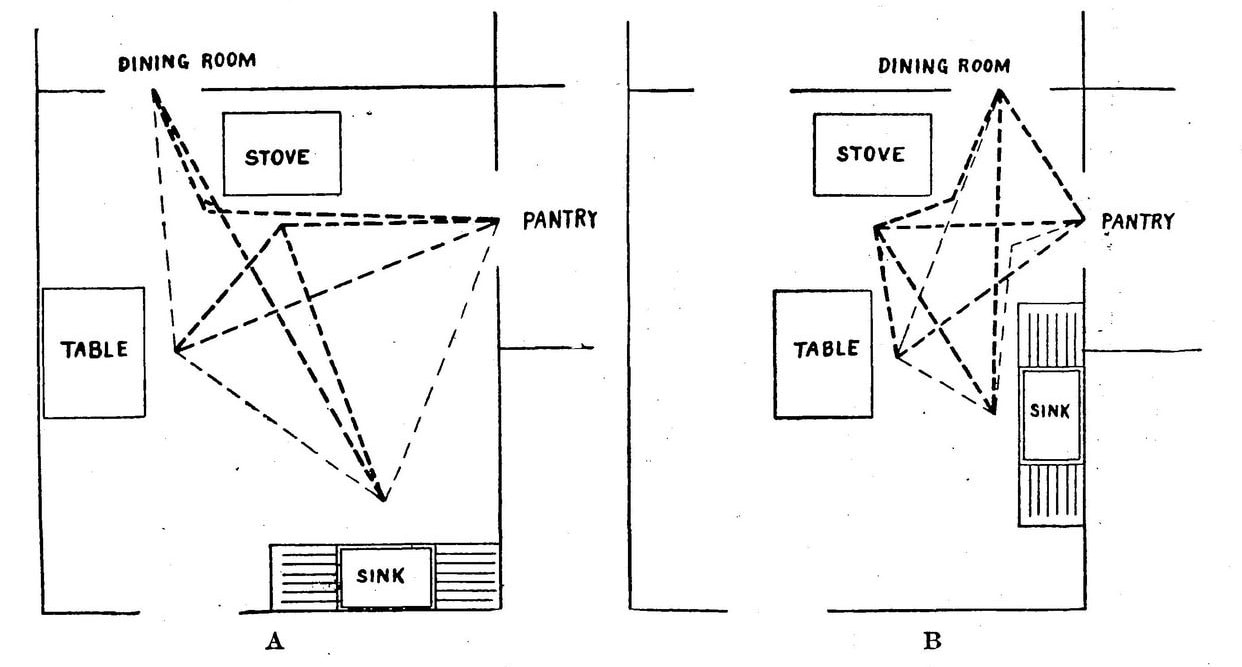

The other night I introduced a friend to one of my favorite YouTube videos ever. It’s a 1949 film put out by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Home Economics. You can watch the whole thing below: I love this film for a variety of reasons, but the primary one is how incredibly FUNCTIONAL this kitchen is. Not everything is perfect. The “messaging center” is too close to the stove for me – too able to collect splatters and grease from cooking. And the table, while nice, I think would have been better served by a more efficient built-in breakfast nook. But everything else? I LOVE IT. The storage is incredible. Everything is built with thought to use and efficiency. From the cooking and cleaning activities to the storage. And while the cabinets aren’t the prettiest, keep in mind that the design is meant to be built by farmers and handy homeowners – not professional contractors. Learn more about the film and the pamphlet for the Step-Saving Kitchen. This kitchen design is the culmination of several decades of work studies. During the Progressive Era, American interest in science began to increase, and scientific theories were applied to everything from factories to households. The Efficiency Movement was part of this application of scientific principles to everyday life. Led by mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor, the movement posited that everyday life, from industry to government to households, were plagued by inefficiencies, which wasted time, energy, and money. It also influenced the ecological conservation movement, a reaction to overuse of natural resources, and President Teddy Roosevelt was a known proponent. The movement, which became known as “Taylorism,” was hugely influential and spurred Progressive Era trust in experts and authorities that continued until the 1960s. Nowhere was Taylorism probably more influential than in the home economics movement, which advocated for efficiency in everything from nutrition to childrearing to household design. And that was thanks in part to the work of Christine Frederick, who in 1912 took Taylor’s principles and applied them to the household with a series of articles on “New Housekeeping” she wrote for the Ladies’ Home Journal. She started a Taylor-style efficiency laboratory in her own home kitchen and went on to publish several more books on the subject, including the 1919 Household Engineering: Scientific Management in the Home. Another influential advocate of household efficiency was psychologist Lillian Gilbreth. With her husband Frank Gilbreth, the two created a partnership to take Taylor’s ideas and apply them to industrial spaces, developing time-and-motion studies. Today, you might know them best as the parents who starred in the book (and subsequent films) Cheaper by the Dozen. After Frank’s untimely death in 1924, Lillian encountered discrimination in the engineering field, and began to turn her talents toward the domestic sphere. Partnering with Mary E. Dillon, president of the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company (and the first female utility president in America), Gilbreth and Dillon developed the kitchen work triangle, which advocated for a step-saving triangle between sink, stove, and refrigerator. Part of Gilbreth’s Practical Kitchen, the new design was revealed at the Eighth Annual Exposition of Women’s Arts and Industries on October 1, 1929. Eleanor Roosevelt was one of the speakers. Many of these principles were adopted by government organizations like the USDA. As early as the 1909, with the federal government’s Country Life studies, the plight of farm women and their poorly designed, technology-lacking kitchens came to light. The USDA’s Farmer’s Bulletin No. 607, “The Farm Kitchen as Workshop,” published in 1921 by Anna Barrows, outlined some of the concerns about kitchen efficiency and how to correct them. Page 10 of the bulletin illustrated the difference in closing the distances between workspaces – a star shape similar to the kitchen work triangle resulted. Several Congressional Acts brought federal funding to these studies. The Smith-Lever Act of 1914 mandated home economics instruction at land grant colleges. The Purnell Act of 1925 allocated federal funding into vitamin research and research of rural home management. These types of studies flourished under the federal funding and in my opinion placed overdue emphasis on the safety, sanitation, comfort, and efficiency of the home. All of these efficiency studies contributed to the result of the 1949 kitchen I love so much. But what happened? Why do modern kitchens seem to ignore the best research of the past? Today, there is far less government investment in domestic study – either from the USDA or public universities. The USDA’s Bureau of Home Economics was shuttered in 1962. Some of its personnel were shifted to the Nutrition and Consumer-Use Research department under the auspices of the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. Some consumer-based research regarding food was absorbed by the FDA. But the kitchen research seems to have largely been abandoned. Some universities, like at Cornell, have continued to offer household design programs as subsets of architectural programs. But the federal funding is gone. Which is a shame, because our household lives seem to have suffered for it. One rule that has been adopted most widely is the kitchen work triangle. But not always. For instance, my kitchen doesn’t have one – the refrigerator, stove, and sink are all in a line. The only triangle is that my primary work surface is on the other side of my galley kitchen. And don’t even get me started on the ergonomics of storage. Those seem to have been discarded wholesale. One ray of light has been the resurgence of roll-out shelves. But even these are few and far between, likely because they are more expensive than traditional fixed shelving. And yes, dear reader, here, I think, is the rub – efficient kitchens must be custom designed. And in our cookie-cutter, prefab world, both design and customization are expensive. In addition, many of today’s kitchens are designed more for show, or occasional entertaining, rather than daily life. Which is an unfortunate reflection of how many Americans cook (or don’t). Case in point: the disappearance of the pantry – the one final thing that 1949 kitchen doesn’t have (it’s presumably in the cellar in the film) that I’d want. At any rate, if I ever win the lottery, you know what kind of kitchen I’ll be building. What aspects of the 1949 Step-Saving Kitchen did you like best? What would your dream kitchen look like? Sources & Further Reading

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

1 Comment

It's Juneteenth! Thanks to everyone who joined us for Food History Happy Hour. This week we make the Rose in June cocktail from the 1917 "Recipes for Mixed Drinks." We discussed Juneteenth, red velvet cake, victory gardens including propaganda and the exclusion of Black farmers and imprisoned Japanese Americans, the role of visuals in influencing taste, Black Food Historians You Should Know, disparities in book contracts, hot weather foods, salads, summer kitchens, how historical peoples coped without air conditioning, how historical peoples kept foods cold before refrigeration, ice and ice cream in the ancient world, rural electrification and electric refrigerators, the Frigidaire Cookbook, icebox pie, racial stereotypes in food advertising, including the history of the "Aunt" and "Uncle" terms, including Uncle Ben and Aunt Jemima, the history of the mammy trope, the tragedy of child caring roles, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Black children in advertising, Franchise: the Golden Arches in Black America, the forthcoming book scanner I ordered, monuments and statues, and we ended with a signal boost for the James Hemings Society.

Rose in June Fizz (1917)

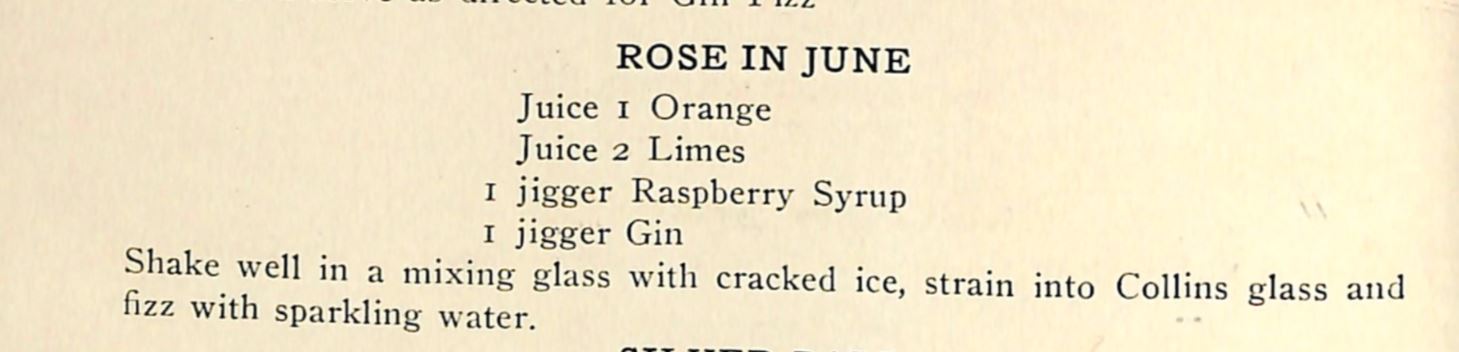

The "Rose in June" cocktail comes from the "Fizz" section of Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo Ensslin (1917).

The original recipe calls for: Juice of 1 orange Juice of 2 limes 1 jigger raspberry syrup 1 jigger gin Shake well in a mixing glass (or cocktail shaker) with cracked ice, strain into Collins glass and fizz with sparkling water OR - if you don't have fresh citrus fruits OR raspberry syrup - you can substitute 1/3 cup orange juice, 1/4 cup lime juice, a heaping tablespoon of raspberry (or in my case, strawberry) jam, and the gin. Very nice, very refreshing, but sadly NOT pink.

Here's a roundup of links related to everything we talked about (in addition to all the links above!):

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

In these days of stay at home orders, lots of folks are cooking at home more. And because we're supposed to grocery shop as infrequently as possible, lots of folks are also stocking up on food. So I thought this United States Department of Agriculture pamphlet (or possibly series of posters) from World War II on how to prevent food waste in storage and use would be fun and might include some bright ideas we can use again today. Published by the Home Economics Department of the USDA, these images are courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Join the ranks - Fight Food Waste in the home

Like during the First World War, preventing food waste in WWII was a way to help keep food supplies freed up for soldiers and the Allies. In addition, canned foods could be scarce from time to time, and so Americans were growing and home canning their own more than ever. In particular, meat and dairy products were precious and sometimes difficult to get, even with ration points. Preventing food waste not only helped secure the food supply, it also saved money. By the 1940s, the majority of Americans had access to electricity and therefore electric refrigeration. But while refrigerator companies wasted no time touting not only the benefits of electric refrigeration, but also how to use fridges, sometimes old habits died hard. Storing dairy products at room temperature, for example. Other old-fashioned wisdom like on how to store fresh vegetables, was sometimes lost. So home economists like those at the USDA took it upon themselves to make sure all Americans had access to correct food safety information. Milk and Eggs - Nature's Food clean, covered, cold... will stay good!

If you're wondering why "clean milk" will only keep a few days in the fridge, it's likely that the milk being referred to in the pamphlet was raw and unpasteurized. You'll notice in the photograph that the woman is placing a glass bottle of milk in the fridge, and quite near the freezer compartment. The rest of the refrigerator is full of glass refrigerator dishes - designed to keep food "clean, covered, and cold." The baby is present to remind parents of the importance of keeping even dessert dishes cold and unspoiled. Meat, Poultry, Fish are full of flavor, a cold dry place is what they favor. The meat dish in refrigerator is an ideal place.

Here again the same woman is putting raw meat in the "meat drawer" of the refrigerator - located directly below the freezer compartment. It appears to be a metal drawer that slides out completely, presumably for ease of cleaning. Most delightful for me are the photographs of the root cellar (center) and spring house (right). Of course, the earth keeps things at a constant 54 degrees F, and spring houses often were full of constantly running water, which not only kept the building cool, but some foods could also be placed in the water to keep them even colder. This was a common way to keep foods cool before electric refrigeration. Hung in the well or sunk in a running stream, the water would leach heat away from the foods and keep them cool. Cooked Meat, Poultry, and Fish

Cooling hot foods quickly before refrigeration is still recommended by health department professionals. Most botulism cases come not from poorly canned foods, but from foods left over overnight or for several days and being reheated and consumed. Save Every Drop of Oil or Fat

Of course during the war, waste fats were saved for munitions manufacturing. But here was have answered the age-old question as to whether or not you should store your bacon grease in a coffee can at room temperature like grandma used to - don't! I recommend a glass container (canning jars are nice) in the fridge or freezer. It lasts forever there, the glass container won't rust, and is easy to clean. Wilt Not, Waste Not.... Fresh Vegetables

I am extremely tempted now to store my celery not in the crisper drawer, but in a jar of water! Of course, finding a place for it to stand upright is difficult... However, you can store cut celery in water - it will become extremely crisp. Fresh corn, garden peas, and young fresh lima beans all convert sugars to starches quite quickly after being picked. Keeping them in their pods helps prevent them from drying out. Fresh Fruits Are Best In Season with care... they'll keep within reason.

If you've ever taken a container of raspberries from the fridge with dismay to see them growing mold, perhaps it would be best to follow this advice. Certainly don't wash berries until just before use. But my goodness - I wish I had the sort of fruit rack pictured above - pears are the hardest by far to keep from spoiling or ripening too quickly. A Cool Airy Place to Suit Hardy Vegetables and Fruit.

I like this wooden storage rack as well, apparently made from wooden fruit crates. Apples and citrus up top, a large cabbage and perhaps onions (with covering) on the second rack, and potatoes, covered to keep from sprouting and turning green, on the bottom. One lament of mine is that modern kitchens almost NEVER have good storage for vegetables like this. To Keep bread, Cake, and Cookies Nice, protect from insects, mold, and mice.

Do you have a bread box? My mother-in-law does, and my parents' house has a built-in bread drawer in the kitchen - made of metal. I do not have a bread box, largely because we keep things in plastic these days and thus don't need the close quarters of the wooden or metal box to keep bread wrapped in paper from drying out. But definitely in July and August I keep my favorite cracked wheat sliced bread in the fridge, otherwise it does mold quite quickly. Sugar - Flour - Cereal - Spice

I am proudest, perhaps, of my baking cupboard, in which almost everything is stored in lovely, air tight glass jars. The brown sugar is never hard, the flour stays fresh, and the dried fruit don't get TOO dry. Storing things in air-tight containers also prevents an infestation of Indian meal moths, which I had the misfortune of dealing with precisely once before I started storing everything in glass. I think they came in with a batch of bulk peanuts in the shell. Of course, they get their name from "Indian meal" - a.k.a cornmeal. They also keep out mice and other insects, although thankfully I have never experienced weevils. The few home-canned foods I have on hand (and homemade booze), I keep in cupboards so they stay in the dark. I have heard of the mysterious and delightful-sounding kitchen accoutrement called a "fruit room" - a cool, dry, dark place perfect for storing not only fresh fruit but canned goods. My dream home has one, along with a butler's pantry. How do you store foods in your home? Do you have a fancy pantry? Or do you make do with kitchen cupboards and a metal rack, like I do? If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

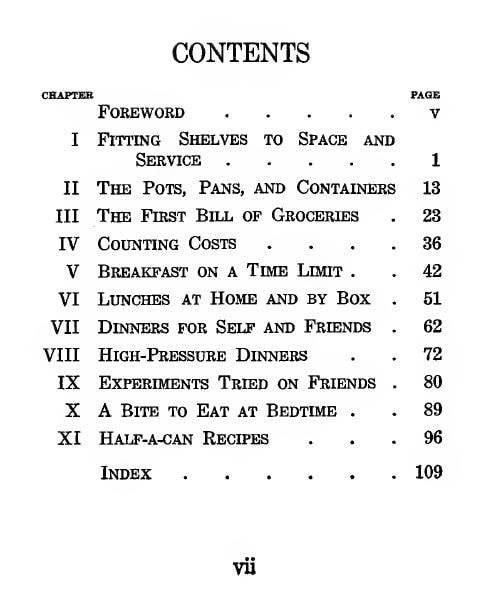

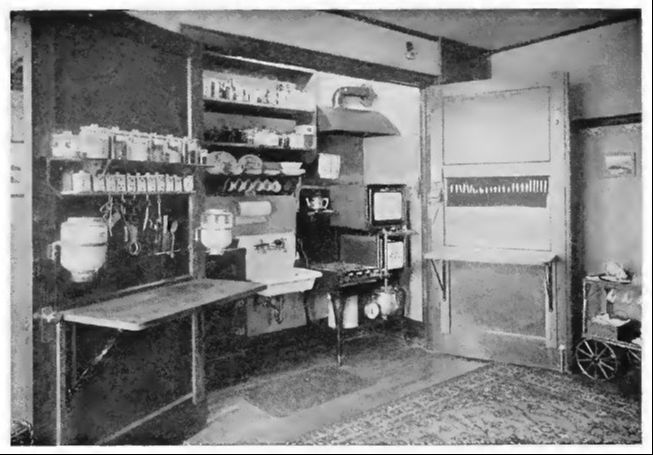

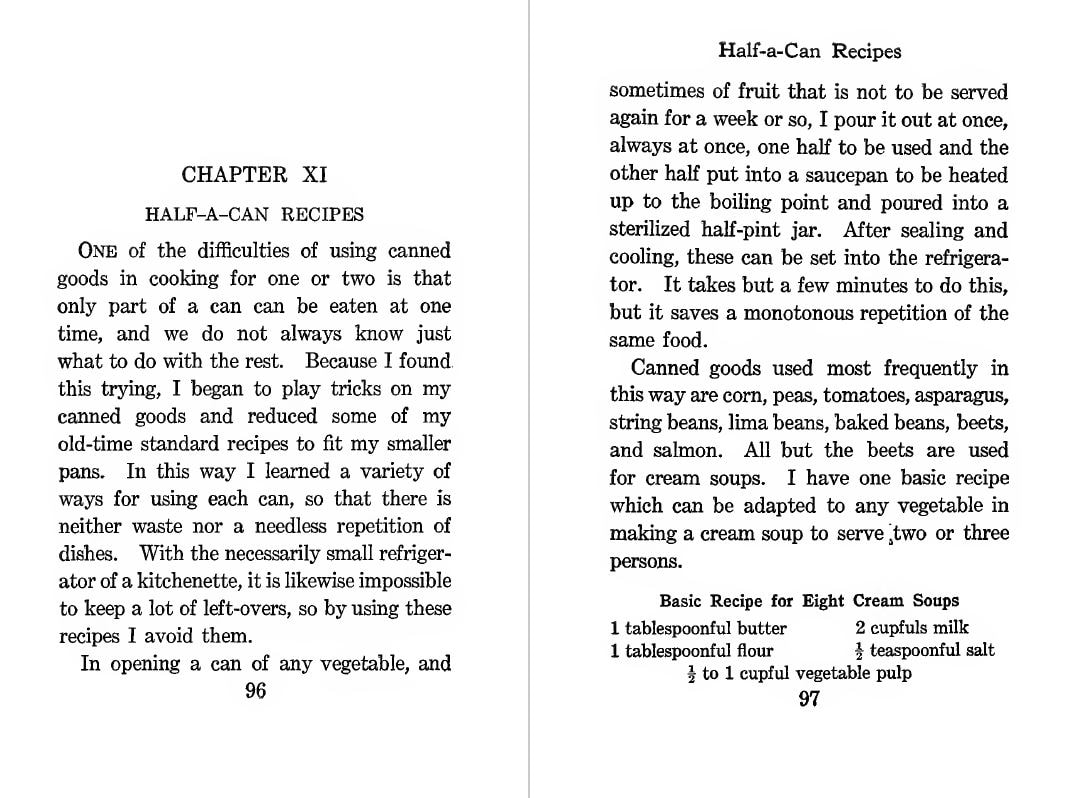

Friend and Patreon patron Anna Katherine posted the most fascinating article the other day. Architectural historian Sarah Archer (so many Sarahs in history work!) has written a great history of the Frankfurt Kitchen. What is the Frankfurt Kitchen, you may ask? Well, you'd be better off just reading the article, but to summarize briefly, it was invented by Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (1897–2000), who was helping to redesign apartment living in European nations recovering from bombing. Her kitchen was a model of efficiency based on the galley kitchens of railroad cars (although, it should be noted that the term "galley kitchen" was first used on ships). So why am I writing about this now? Because I've long had a fascination with the time of transition in American history when ordinary middle-class Americans had to shift from having live-in servants to doing their own work. And when "young brides" were thrown to the winds of married life with a high school or college education, but little idea of how to manage things on their own. Enter, "Kitchenette Cookery," by Anna Merritt East, originally published in May, 1917. I stumbled across Kitchenette Cookery on the Internet Archive (bless it forever), and it's a delightful snippet of life at the start of World War I (for the US, anyway). Anna Merritt East graduated from the University of Nebraska in 1912 and was, for a time, the "New Housekeeping Editor" for the Ladies' Home Journal. Unfortunately that's about all I can find out about her and "Kitchenette Cookery." The book really is designed for young women setting up a household for the first time, probably on a tight budget. Not only are the first chapters about setting up and kitting out the kitchenette, there are also two whole chapters on shopping and budgeting. But the recipe chapters are my favorites. "Breakfast on a Time Limit" talks about using the apartment building's hot water system to help hurry up coffee percolating and how to get a hot breakfast on the table in time for the husband to catch the "bus" to work. "High-Pressure Dinners" is a great deal about Anna's beloved pressure-cooker, with which she happily entertains guests who, of course, watch her cook in her tiny kitchen. The book itself is delightful from a historical standpoint, although sadly it has some rather poor reviews on Goodreads and elsewhere. Unlike many other books from the period, it has no real introduction to speak of, so sadly we get no real idea of where Anna's kitchen is, or if this is her real, everyday kitchen, although it appears so. Her kitchen, pictured above, is really just a closet with two very large doors. The door on the left serves as a sort of Hoosier cupboard, with flour storage/sifter, a folding wooden cutting board/work surface, and narrow shelves holding spices and what appear to be other baking supplies. Another folding wooden shelf lines the other door, with what appears to be an ingenious fabric pocket for silverware. Within the closet it an open shelf for dishes above the small sink, with what appears to be a roll of paper towels above. The tiny gas stove is at right and tucked into the corner by the front door (off frame at right) is a rolling tea cart. Here we see one door closed to illustrate how the kitchen can be closed off completely when time to dine at the tiny table, also folding. The tea cart is also in use for service. Although ingenious, this really is a "kitchenette" in the truest sense of the word - a kitchen in almost miniature, designed to provide the most basic functions. Although there is no floor plan for the whole apartment, it really must be either a one bedroom or studio. Apartments in large Eastern cities (this one is presumably in Boston) were often carved up out of former mansions or multi-level apartments (as they still are today), and thus were often cramped into small spaces not designed to be whole living quarters. This is another favorite chapter, in which Anna discusses the awful occurrence of having half a can of whatever - usually a vegetable - left over from making dinner for just two. Anna writes, "One of the difficulties of using canned goods in cooking for one or two is that only part of a can can be eaten at one time, and we do not always know just what to do with the rest. Because I found this trying, I began to play tricks on my canned goods and reduced some of my old-time standard recipes to fit my smaller pans. In this way I learned a variety of ways for using each can, so that there is neither waste nor a needless repetition of dishes. With the necessarily small refrigerator of a kitchenette, it is likewise impossible to keep a lot of left-overs, so by using these recipes I avoid them." My other favorite chapter (technically second-to-last, but seeming more apropos to be the end to this little blog post), is "A Bite to Eat at Bedtime," because who doesn't want a midnight snack these days? Her recipes mostly involve a lot of canned seafood, but I thought this fascinating little onion and cream cheese sandwich might actually be delicious, although serving with coffee is dubious - I think a cold beer or cider might be better. Of course, Anna was probably a good Prohibitionist, because as far as I can tell, there's nary a mention of wine or spirits in this little book. If you liked "Kitchenette Cookery" as much as I do, you can download the whole book from the Internet Archive. Funnily enough, my little kitchen (although MUCH bigger than Anna's) is a roomy galley kitchen. My little house was built about 1941 and out of bits of older houses (narrowboard floors and Victorian glass doorknobs, plus old-fashioned paned wooden windows, and a bluestone fireplace on a side porch), so the galley kitchen may have been inspired by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and her Frankfurt Kitchen! What is your kitchen like? Do you have an enormous roomy one? Or a tiny kitchenette like Annas? Let me know in the comments! And, as always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed