|

It's that time of year when people all over the world are thinking about graduating, either from high school or college. The question in so many minds is, "What's next?" High school students are considering what they should major in, whether they should do a summer internship or get a job, what they want their adult lives to look like. College students are doing much the same - considering whether to attend graduate school, try for an internship, get an entry-level job. And many of them are considering food history as a career option. When you call yourself "THE" food historian, you get a lot of questions about how to break into the field. After answering lots of individual emails, I've decided to tackle the subject in this blog post. I'll be breaking down what it takes to be a food historian, but first I want to emphasize that making a career out of history can be difficult, and it is not particularly lucrative. Even those with PhDs in their fields have trouble finding jobs. I myself work in the history museum field (more job opportunities, but the salaries are usually low) and do the work of a food historian as a passion project that occasionally pays me. That being said, there are folks who are able to make a living through freelance writing, being history professors (food history and food studies programs are expanding in academia), working in museums, writing books, consulting on films, and even making YouTube videos and podcasts. It's not easy, and it's generally not lucrative, but if you have a passion for history and food, this may just be the route for you. A few other folks have written on this subject, notably Rachel Laudan. But while I think she has some great advice on the work of doing food history, that's not quite the same thing as being a food historian. The Inclusive Historian's Handbook, which is a resource for public historians, has also written about food history, albeit in a forum meant for public historians and museum professionals. So I thought I'd tackle my own definitions and advice. I should note that this guide is going to be necessarily focused on the field of food history in the United States, because that is my lived experience, but most of the basic advice is applicable beyond the U.S. What is food history?First, let's do a little defining. I use the term "food history" in the broadest sense. It encompasses:

Food is the one constant that connects all humans throughout human history. Which is part of why it is so appealing to so many people, including non-historians. The History of Food HistoryProfessor and food historian Dr. Steven Caplan of Cornell University has written on the history of the field, but here's my own summary. Although agricultural history has a long and storied past, until quite recently food history was considered an unserious topic of study in academia. Even after the social history revolution of the 1970s, which coincided with a groundswell of public interest in the past thanks to the American Bicentennial, food history was largely considered the purview of museum professionals, reenactors, and non-historians. Even trailblazing scholars like Dr. Jessica B. Harris approached food history from an oblique angle - she has a background as a journalist, her doctoral dissertation was on French language theatre in Senegal, and she was a professor in the English Department at Queens College in New York City for decades. And yet her groundbreaking books helped set the tone for subsequent historians. In fact, many of the food history books published in the last fifty years have been written by non-historians - largely journalists and food writers. And while many fine works have come out of that technique, as someone who has a background in both cooking and academic history, there are often missed opportunities in food history books written by both non-historians and non-cooking academics alike. So why has food history been deemed so unserious? A couple of reasons. One was that gatekeepers in the ivory tower didn't consider food an important topic. It was such a ubiquitous, everyday thing. It seemed to have little importance in the grand scheme of big personalities and big events. But I think its very ubiquity is part of the reason why food history is so compelling and important. Another reason was that the primary actors throughout food history were not generally wealthy White European men. They were (and often still are) primarily women and people of color - producing and growing food, preparing, cooking, preserving, and serving it. Racism and sexism influenced whose history got told, and whose didn't. You can still see some of this bias in modern food history, which often still focuses on rich White dudes with name recognition. Then, when people began studying social history in the 1960s and '70s, food history largely remained the work of museums, historical societies, and historical reconstructions like Old Sturbridge Village and Colonial Williamsburg. It was popular, and therefore not serious. Real food historians knew better. They persisted, but it was a long slog. Let's take a look at a brief (and very incomplete) timeline of food history in the United States since the Bicentennial: In 1973, British historian and novelist Reay Tannahill published Food in History, which was so popular it was reprinted multiple times over the following decades. In 1980, the Culinary Historians of Boston was founded. In 1985, the Culinary Historians of New York was founded. In 1989, museum professional Sandra (Sandy) Oliver began The Food History News, a print newsletter (a zine, if you will) dedicated to the study and recreation of historical foodways. Largely consumed by reenactors, museum professionals, and food history buffs, the publication of the newsletter sadly ceased in 2010. I am lucky enough to have been given a large portion of the print run by a friend, but Sandy's voice is missed in the food history publication sphere. In 1999, librarian Lynne Olver created the Food Timeline website, dedicated to busting myths and answering food history questions. Lynne sadly passed away in 2015, but in 2020 Virginia Tech adopted the Food Timeline and Lynne's enormous food history library. Lynne herself published some food history research recommendations as well. The Food Timeline is likely responsible for many a budding food historian, as it is incredibly fascinating to fall down the many rabbit holes contained therein. In 1994, Andrew F. Smith published The Tomato in American Early History, Culture, and Cookery. He joined the New School faculty in 1996, starting their Food Studies program. He has since gone on to publish dozens of food history books and is the managing editor of the Edible series, which began in 2008 under Reaktion Press, now published by the University of Chicago Press. In 1998, food and nutrition professor Amy Bentley published Eating for Victory - one of the first-ever history books to tackle food in the United States during World War II. In 2003, the University of California Press started its food history imprint with Harvey Levenstein's Revolution at the Table. Levenstein is an academically trained social historian and helped reinvent food history's brand as a serious topic for "real" historians to tackle. In the last 20 years, the study of food history has exploded. Dozens of books are published each year, and more and more people are choosing food as a lens to study all kinds of things, with history at the forefront. Food history has increasingly become a serious field of study, and more and more academically trained historians are bringing their skills to the field, helping shift the historiography. Even so, issues persist. Until very recently, the broad focus of American food history was still very White, and very middle- and upper-class, in large part because those were the folks who published the most cookbooks and magazine articles, who owned and patronized restaurants, who built food processing companies, etc. Low hanging fruit, and all that. The field is diversifying, but the assumption that American food is White Anglo-Saxon persists. Like bias in general, it takes constant work to overcome. Problems in Food HistoryBecause food history is so popular, and so many non-historians have contributed to the historiography, issues that plague all popular subjects persist. First, food history is FULL of apocryphal stories and legends. Many of these continue because non-historians take primary and secondary sources at face value without critical thinking. Many food history books published by non-historians and/or in the popular press do not contain citations. Sometimes this is a design choice by the publisher and not a reflection on the scholarship of the historian. But sometimes this is because the writer is simply regurgitating legends they found somewhere questionable. Food historians need to delve deeply, think critically, and amass corroborating evidence when at all possible. Mythbusting is an important part of the field. Second, non-historians tend to take foods out of context and make assumptions about the people in the past. In the United States, the general public simultaneously romanticizes our food past (yes, there were pesticides before World War II, no, not everyone knew how to cook well) and vilifies difference. I'm sure you've seen all of the memes and comments making fun of foods of the past (I've tackled a few of them here and here). The idea that tastes or priorities might change boggles the minds of folks who are stuck in the mindset of the present. But historical peoples were diverse, circumstances (like central heating and air conditioning) changed frequently, and both had a big impact on how and why people ate what they did. While we can't excuse moral issues like racism, sexism, and xenophobia, it's important to note that there were always people in the past fighting against those isms, too. Rejection of those mindsets is not a uniquely modern idea. The idea that modern humans are somehow morally better, smarter, more sensitive, etc. than historical peoples is not only wrong, it is dangerous, because it implies that we are somehow so advanced that we do not need to self-critique. Nothing could be further from the truth. Third, many of the research questions I and many food historians get from journalists and students tend to focus on origin stories of certain foods. Some are provable, most are not, and most confoundingly for the folks who want to know who did it FIRST, sometimes certain types of foods crop up simultaneously in unrelated places. The real issue with these questions is, who cares who made the first eclair? I mean, maybe you do, but what does finding out who made the first eclair tell us about food history? Perhaps you might argue that it was a turning point in the history of French baking, and went on to influence global fashion for decades to come. You might be right. But if your question is "who did it first?" instead of "what are the wider implications of this event?" or "what does this tell us about the time and place in which it was created?" or "how did this influence how we do things today?" you're asking the wrong questions. We ask "who cares?" a lot in the museum field. To be a good educator and communicator of history, you must make it not only understandable, but relevant to your audience. The origin of the tomato is largely unimportant except as an exercise in research unless you can connect it somehow to our modern society and make people care. On the flip side of things, and finally, there is a lot of gatekeeping in academia about food history. I've actually seen academics bemoan the idea of using food as a lens to study broader historical ideas, instead of focusing only on the food. Which is ridiculous. That's like saying the history of clothing has to focus only on the physical clothes themselves, and not the people who wore them, the society that created them, or the political, economic, and/or religious meaning behind them. Food history is meant to illuminate the hows and whys behind what is probably the biggest and most pervasive driving force behind most of human history - the acquisition and consumption of food. Focusing only on individual dishes doesn't improve food history - it dilutes it. Thankfully, many of these problems can be solved by following two simple truths. To be a food historian, you must first be a historian, and you must also know food. To be a food historian, you must first be a historianThis is a tough one for a lot of folks. The word "historian" conjures up old men with white beards and tweed jackets sitting in book-filled academic offices. But a historian is less a specific person and more a set of skills and experiences. And food history differs from food studies in that it has a primary focus on history. Food studies is an increasingly popular field, especially for colleges and universities that want to attract students with diverse interests. But in my personal opinion, a lot of the work coming out of food studies programs lacks the rigor of history training. I base this judgement on some of the work I've seen presented at conferences. Doesn't mean there aren't fine folks in food studies, and mediocre folks in food history, but the broadness of the food studies umbrella seems to allow for a looser interpretation of the subject than I'd prefer. History is evidence-based, and the best history not only requires corroborating evidence, but also an examination of what is not present in the historical record, and why. Historians also produce original research, which is the primary difference between a history buff and a historian. History buffs can be subject experts and have read all the secondary sources on a topic, and even primary sources. But you're not a historian until you're producing original research. The medium for that research can take many forms. The most common are articles, conference papers, and books. But original research can also be presented in documentary films, podcasts, museum exhibits, etc. Public historians are the same as academic historians with one distinct difference: audience. A public historian's audience is the general public, and they must adjust their communications accordingly. Public historians use less jargon and give more context because their audience tends to have less foreknowledge of the subject. Although many academic historians are starting to see the public history light, many still have other academics as their primary audience, which leads to dry, jargon-y work that that is often purposely difficult to read and comprehend, designed so that only a few of their colleagues can fully understand it. I mentioned earlier that a lot of food history books have been written by journalists and food writers. On the one hand, this is a great thing. The writing quality is better and more approachable, and journalists in particular can be dogged about tracking down primary sources and following leads. But there are issues with non-historians writing history. Mainly, they miss stuff. Many journalists write food histories as one-offs, moving onto the next, usually unrelated topic. And food writers tend to focus more on what they know - cooking and eating - rather than what's happening more broadly in the time period they're examining, and how their research fits into that. Because neither group tends to have a breadth of knowledge about the time period or culture they are examining, they often overlook connections, make assumptions that aren't necessarily supported by the evidence, and generally miss a lot of cues that historians trained in that time period would pick up on. That stuff is usually called context. Context is the background knowledge of what is influencing a moment in history. It's the foreknowledge of the history that leads up to a moment, the understanding of the culture in which the moment is taking place, grasping the relationships between the historical actors involved in the moment, etc. I'll give you an example. Promontory, Utah, 1869. If you know your history, you'll know that's the date and place where the two sections of the transcontinental railroad were joined. If you didn't know the context around that event, you might consider it a rather unimportant local celebration of the completion of a section of railroad track. But the context that surrounds it - the technology history of railroads, the political history of the United States emerging from the Civil War, the backdrop of the Indian Wars and the federal government's land grabs and attempted genocide, the economic history of railroad barons and pioneers - this context is all incredibly important to fully understanding the Promontory Summit event and its significance in American history. Journalists are great at the who, what, where, when, and even how. They're less great at the context. History is more than reciting facts. It is more than discovering new things and rebutting the arguments of historians who came before you. History, especially food history, is about the why. When I was in undergrad, it was the why that drove me. My first introduction was via agricultural history. I was interested in history, but also in the environment, and sustainable agriculture was my gateway into the world of agricultural history. I wanted to know not only how our modern food system came into being, but also why it was the way it was. I was also deeply interested in eating, and therefore in learning how to cook, although it would take until my senior year in college to actually do much of it. A burgeoning interest in collecting vintage cookbooks helped. From there I researched rural sociology and the Progressive Era in graduate school, and that sparked my Master's thesis on food in World War I, and the rest is history (pun intended). I'm now obsessed. Thankfully, being a historian is a lot less difficult than a lot of people assume. Like most skills, it just takes practice and time. If you like to read and write, you're curious, you are good at remembering and synthesizing information, and you're a good communicator, history might be your perfect field. It requires a lot of close reading, critical thinking, and the ability to organize information into coherent arguments and compelling stories. History is simultaneously wonderful and horrible because it is constantly expanding. Not only thanks to linear time, but also because new evidence is being discovered all the time and new research is being published daily. It's both an incredible opportunity and a daunting task. But with the right area of focus, it becomes not a boring task, but a lifelong passion. To be a food historian, you must also know foodThis is one some academics sometimes struggle with. Like journalists, they have can also have an incomplete understanding of their subject matter. I learned to cook not at my grandmother's knee, or even my mother's. I am self-taught, largely because I love to eat and eating mediocre food is a sad chore. But I did not start cooking for myself until late in college, and even then my first attempts were pretty disastrous. But while failure is a necessary component of learning any new skill, I dislike it enough to be highly motivated to avoid making the same mistake twice, and will take steps to avoid making subsequent mistakes. I'm pretty risk-averse. As an avid reader, I decided that books would be my salvation. I started collecting vintage cookbooks in high school thanks to a mother who passed on a love of both reading and thrifting. I read cookbooks like some people read novels - usually before bed. I got picky with my collecting. If a cookbook didn't have good headnotes, it was out. I wanted scratch cooking, but approachable, with modern measurements and equipment and not too many unfamiliar ingredients. Cookbooks published between 1920 and 1950 largely fit the bill, and I read lots of them. In grad school I expanded my cookbook reading, thanks in large part to Amazon's Kindle readers, which had hundreds of free public domain cookbooks, all published before the 1920s. Then I discovered the Internet Archive, and other historical cookbook repositories with digital collections. All the while I was learning to cook for myself, my roommates, and eventually my boyfriend (now husband). I worked in a French patisserie/coffee shop after college and honed my palate. I tried new recipes often and taught myself to be a good cook and a competent baker. I began to understand historical cooking through recipes. I mentally filed away hundreds of old-fashioned cooking tips. I thought about the best and most efficient ways to do things. I got confident enough to learn to adjust and alter recipes. I experimented. I made predictions and tested them. I learned from my failures and adjusted accordingly. In short - I learned to cook. But I still didn't consider myself a food historian. It seemed too big. I felt too inexperienced, despite all my research, both historical and culinary. Then, I had an epiphany. I attended a food history program with a friend. It had a lecture and a meal component. The lecture was good, but the speaker (who was not an academic historian) mocked a historical foodway I knew to be common in the time period. When I tried to call her on it after her talk, she brushed me off. Then, during the delicious meal, the organizer apologized that one of the dishes didn't turn out quite right, despite following the historical recipe exactly. I knew immediately the step they had missed, which probably was not in the recipe and which wasn't common knowledge except to someone who had studied historic cooking extensively. It was then I realized that there I was, a "mere" graduate student, and I had more depth and breadth of knowledge in food history than these two professional presenters. It was then I decided I could officially call myself a food historian. And that led me to write my Master's thesis on food history and launch this website. In the intervening years, I've often caught small (and occasionally not-so-small) food-related errors in academic history books. Assumptions, missed connections, misinterpretations of the primary sources, etc. It taught me that to be a food historian, you really have to know agriculture and food varieties, food preparation, how to read a recipe, and historical technologies to really understand the history you're studying. If that seems like a lot, it can be. But like learning to cook, doing the work of historical research is about building on the work that came before you. Both the work of other historians, and your own knowledge. We learn by doing, and through practice we improve. Understanding and starting food history research and writingSo now that we've got our terms straight, and we know we need to be well-versed in both history and food, what exactly do I mean by original research? Original research is based in primary sources and covers a topic or makes an argument that is not already present in the historiography (the published work of other historians). Some history topics are difficult to find original research to publish. The American Revolution and the American Civil War are two notable examples of this. There are few unexamined primary sources and the historiography is both wide and deep. Food history does not usually have this problem. In fact, several historians have recently focused on the food history of both the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. Because it has been so understudied, food is one of the few avenues left to explore in these otherwise crowded fields. World War I American home front history, however, is criminally under-studied, especially the field of food history (the Brits are better at it than us). Which is one of the reasons why I chose WWI as my area of focus. One major pitfall budding historians stumble into is the idea that you do research to prove a theory. Nope. Not with history. You should formulate a question you want to answer to help guide you and get you started. But cherry picking evidence to support your pet theory is not history. Real historians go where the research takes them. Sometimes your question doesn't have an answer because the evidence doesn't exist, or hasn't been discovered yet. Sometimes your pet theory is wrong. And that's okay! It's all part of the process. Even when you hit a dead end, you don't really fail, because you learned a lot along the way, including that your theory was not correct. And sometimes the research leads you to discover something you weren't even looking for, and that's often where the magic happens. Secondary Sources Food history research, like all history research, has a couple of levels. The first is secondary source material. This is your historiography - the works in and related to your area of study that other historians have already written and published. Books, journal articles, theses and dissertations are the best secondary sources because they generally use citations and can therefore be fact-checked. Secondary sources without footnotes should be taken with a large grain of salt. Any history that doesn't tell you where the evidence came from is suspect. I say this as someone who dislikes the work of footnoting intensely. But it's a necessary evil. But while secondary sources are usually written by experienced historians, they aren't always perfectly correct. Sometimes new research has been done since the book you're reading has been published, which is why it's important to read the recent research as well as the classics. Sometimes the historian writing the book makes a mistake (it happens). Sometimes the writer has biases they are blind to, which need to be taken into account when absorbing their research. Secondary sources can be both a blessing and a bane. A blessing, because you can build on their research instead of having to do everything from scratch. And a bane, because sometimes someone has already written on your beloved topic! Thankfully, there's almost always room for new interpretations. A good practice to truly understand a secondary source is to write an academic book review of it. Book reviews force you not only to closely analyze the text, but also to understand the author's primary arguments, evaluate their sources, and look at the book within the context of the wider historiography. Primary Sources The second level of research is primary sources. This is the historical evidence created in the period you're studying: letters, diaries, newspaper articles, magazines and periodicals, ephemera, photographs, paintings and sketches, laws and lawsuits, wills and inventories, account books and receipts, census records and government reports, etc. Primary sources also include objects, audio recordings (along with oral histories), historic film, etc. Primary sources generally live in collections held in trust and managed by public entities like museums, historical societies, archives, universities, and public libraries. Some folks like to insist that some primary sources are not primary sources at all, notably oral histories and sometimes even newspaper articles, because the author's memory or understanding of an event may not be accurate. But here's the deal, folks - pretty much no primary source is going to be a 100% accurate account of what is happening in history. The creators all have their biases, faulty memories, assumptions, etc. to contend with. Just because someone was present at a major event doesn't mean they're recording it correctly. It also doesn't mean they saw the whole thing, understood what they saw, or aren't completely lying about their presence there. Nobody has a time machine to go fact-check their accuracy, which is why corroborating evidence is important. ALL primary sources deserve some skepticism and an understanding of the culture that produced them. I should also note that primary sources only exist because someone saved them. And that "someone" historically was middle and upper-class White men. Which means a lot of historical documentation did NOT get saved. In particular, the work of women and especially people of color was not only not saved, sometimes it was actively destroyed. And even when those sources do exist, they can be hard to find, and are therefore often overlooked or ignored by the historians who have come before you. This is part of the skepticism of primary sources, too. Again, what is not present can be just as important as what is. Context And that's the third, often-overlooked level of research: context. We've defined it before. It can be a major stumbling block for non-historians. Context is when you take all the stuff you've learned from your secondary sources, and the cumulative knowledge of the primary sources you're studying, and put it into action. It's reading between the lines, understanding cultural cues, realizing what your primary sources aren't saying, who's absent, and what topics are being avoided. Context is understanding why historical figures do what they do, not just how. It can be easy to get wrapped up in the primary sources. I get it. They're fascinating! I've dived down many a primary source rabbit hole. But we have to think critically about them. Taking primary sources at face value has gotten a lot of historians into trouble, leading them to make assumptions about the past, to accept one perspective as gospel truth, and to overlook other avenues of research. No one source (or one person) ever has all the answers. Writing And finally, the last step of research: the writing. Some folks never make it to this point, just amassing research endlessly. And for history buffs, that's okay. But historians have to leave their mark on the historiography. There are a few important things I've learned in the course of writing my own book. First, get the words on the page. When it comes to writing history, get it on the page first, and then think about your argument, the organization of your article or chapter, the chronology, etc. You can't edit what isn't there, and editing is just as if not more important than writing. Everyone needs to be edited, and all works are strengthened by judicious paring and rewriting. You can always edit, cut, rearrange, rewrite, and/or add to anything you write. In fact, you probably should! I'll give an example. When I'm writing an academic book review, I'll usually write out my first reactions in a way-too-long Word document. Then, once I'm satisfied I've covered all the bases, I'll start a new Word doc and rewrite the whole thing, summarizing, examining my gut reactions, and modulating my tone for the audience I'm writing for. Second, practice makes perfect. The more you write (and read), the better you'll get at it. You'll get better at formulating arguments, explaining things, writing for a specific audience, and just better at communicating overall. So many writers feel shame about their early works. I get it! Sometimes I cringe when I see my early stuff. But sometimes I'm retroactively impressed, too. You've got to put out buds if you want to grow leaves and branches. So write the book reviews, write the blog posts, submit journal articles, etc. Everything you do gets you a step further down the historian road. Third, it's important to know when to stop researching. You need enough research to be well-versed enough to do the work. But perfection is the enemy of done. If you can afford to spend decades researching and refining a single book, by all means please do so. But if you want a career in food history, you're gonna have to be more efficient than that. Finally, and this is the hardest one. You have to learn to kill your darlings. I learned that phrase from a professional writer friend. Just because you're endlessly fascinated by the COOL THING! you found, doesn't mean it should go in your book. If it doesn't advance your argument or is otherwise superfluous information, cut it. I'm at that stage now with my own book, and while it's painful, killing your darlings doesn't meant deleting them! Save them for future projects, turn them into blog posts or podcasts or YouTube videos if you like. But getting rid of the extraneous stuff will make your work so much stronger. Still want to be a food historian?Whew! You made it this far! You may be feeling daunted by now. That isn't my intent. Like learning to cook, doing the work of history takes practice. Start with a topic or time period you're interested in. Look to see if anyone else has already published anything on that topic, and read it. Expand your reading beyond your immediate topic to related topics. For instance, if you want to study food in the Civil War, read not only about food, but about war, politics, gender, agriculture, race, economics, etc. in the Civil War, too. See if your local public or university library has remote access to places like JSTOR, Newspapers.com, ProQuest, Project Muse. See if your local library or historical society has any archival records related to your topic. Scour places like the Internet Archive, the Library of Congress, HathiTrust, and the Digital Public Library of America for other primary sources. Many have been digitized and more are being digitized daily. Start looking, start reading, and start synthesizing what you've learned into writing of your own. If you're thinking of pursuing food history on the graduate level, look for universities with professors whose work you admire and respect, for places with rich food history collections, and for programs that excite you. I worked my way through graduate school, working in museums while getting my master's part-time. I also took two years off between undergrad and graduate school, trying to gain experience in my field before tackling the commitment of grad school. I heartily recommend trying the work of food history before you dive into academia. Finally, food history can be FUN! If this all seems like a lot of work, then maybe food history isn't for you, or perhaps you'd like to remain a food history buff, instead of a food historian. But if the idea of delving into primary sources, devouring secondary source material, learning everything you can about a topic, and then writing it all down to share with others excites you, congratulations! You're already well on your way to becoming a food historian, whether you want to make it your full-time career, or just a fun hobby. Whatever you decide - good luck and good hunting! Your friend in food history, Sarah The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

1 Comment

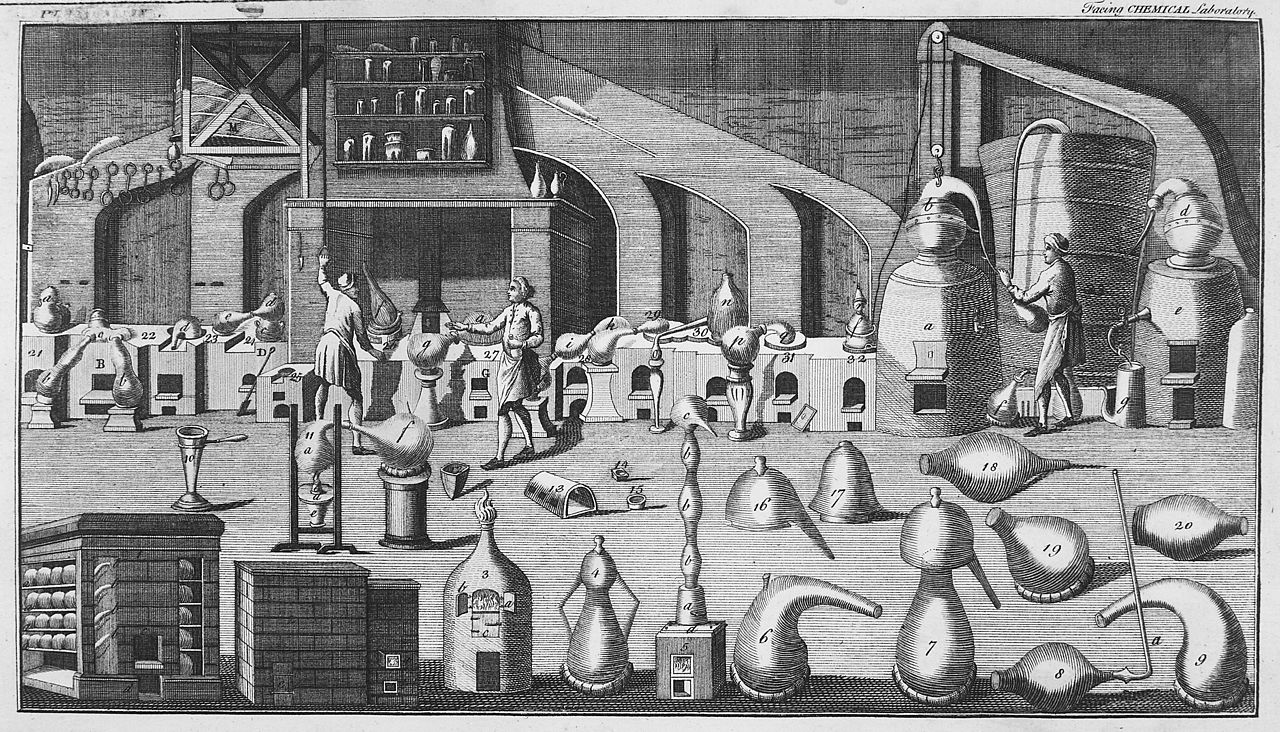

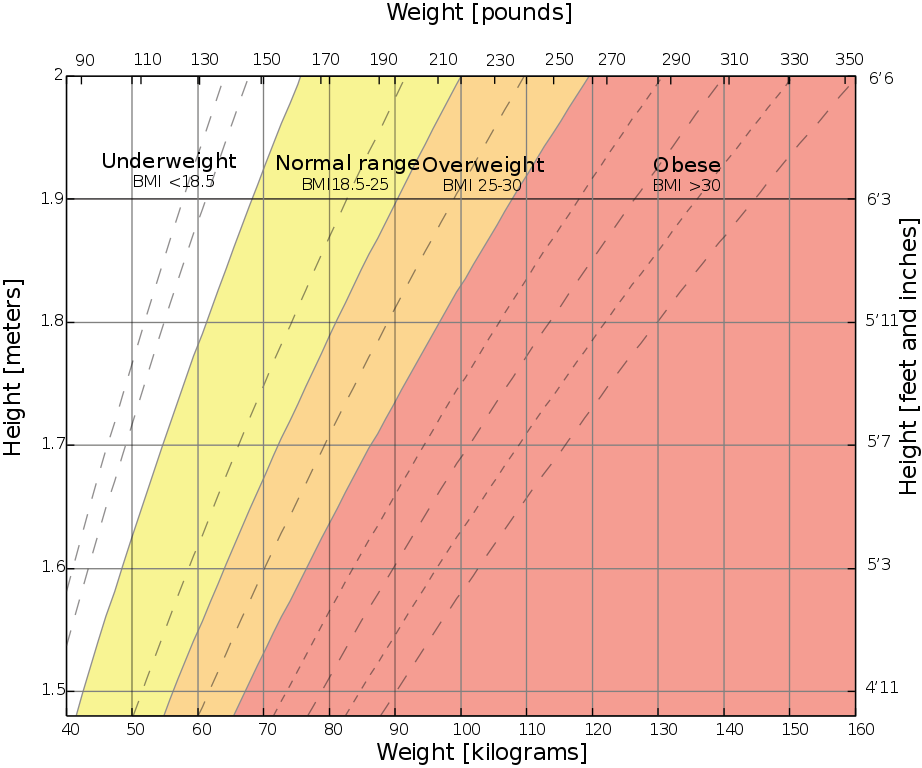

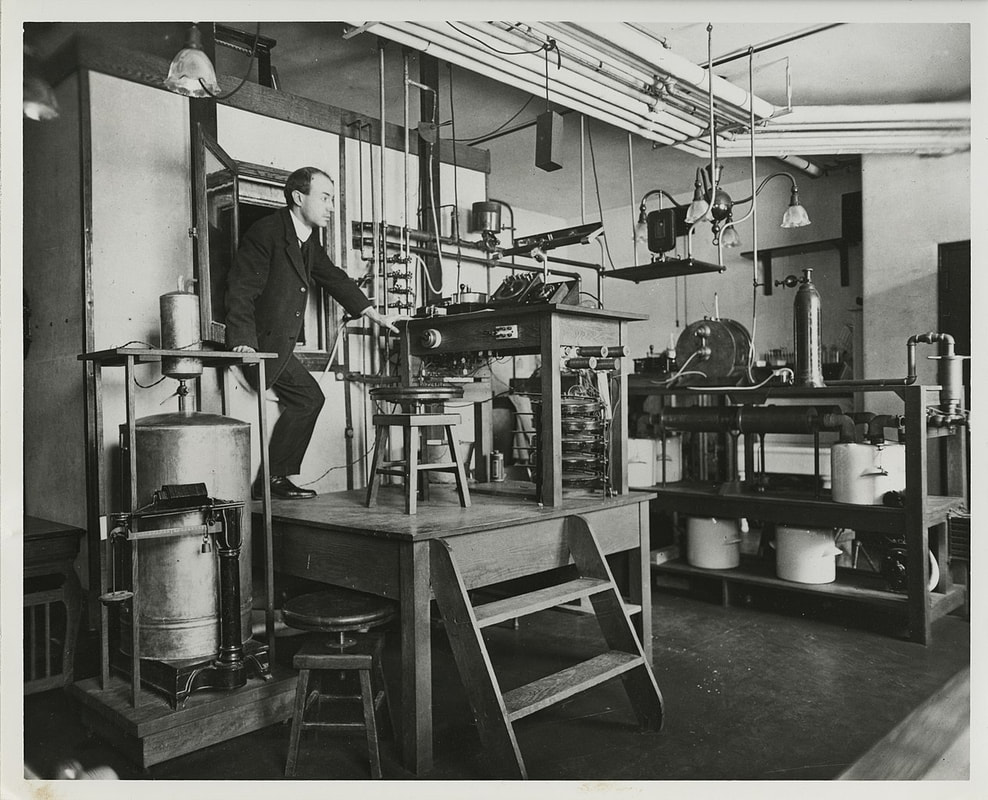

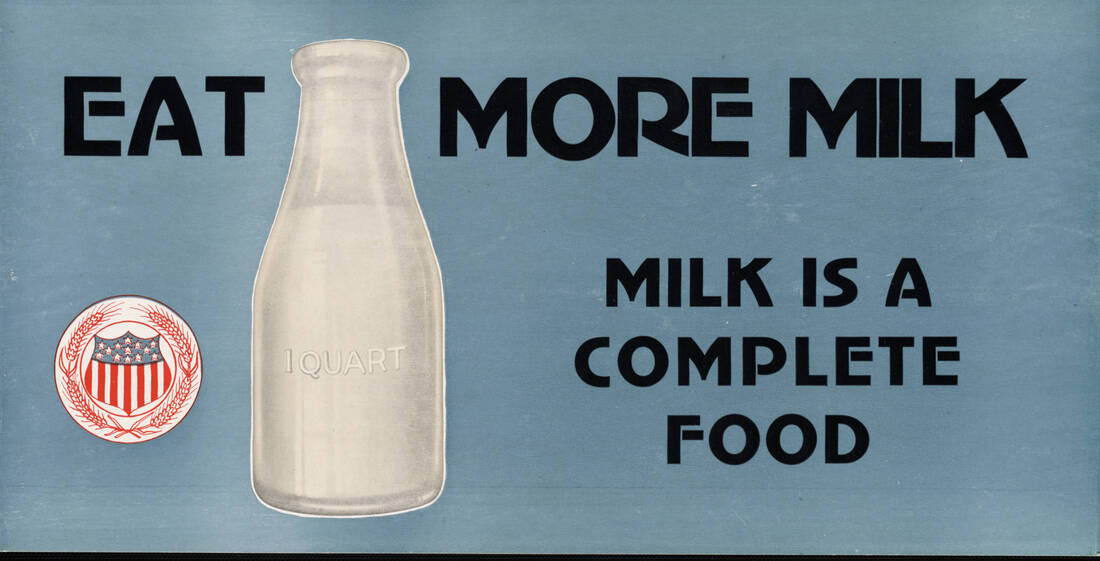

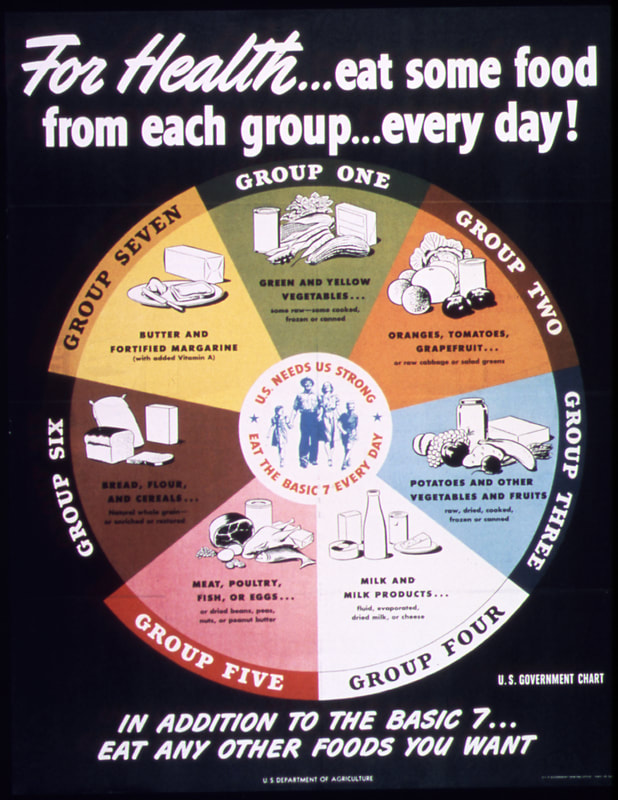

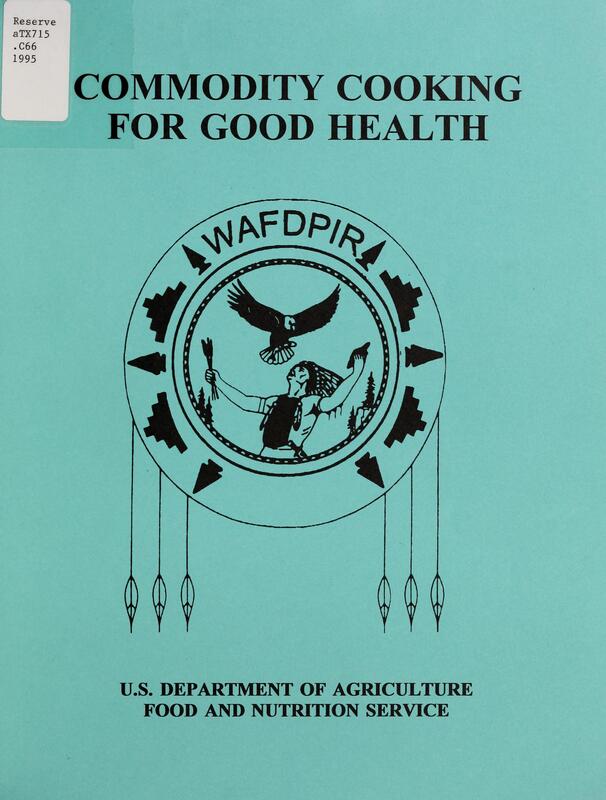

The short answer? At least in the United States? Yes. Let's look at the history and the reasons why. I post a lot of propaganda posters for World War Wednesday, and although it is implied, I don't point out often enough that they are just that - propaganda. They are designed to alter peoples' behavioral patterns using a combination of persuasion, authority, peer pressure, and unrealistic portrayals of culture and society. In the last several months of sharing propaganda posters on social media for World War Wednesday, I've gotten a couple of comments on how much they reflect an exclusively White perspective. Although White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture was the dominant culture in the United States at the time, it was certainly not the only culture. And its dominance was the result of White supremacy and racism. This is reflected in the nutritional guidelines and nutrition science research of the time. The First World War takes place during the Progressive Era under a president who re-segregated federal workplaces that had been integrated since Reconstruction. It was also a time when eugenics was in full swing, and the burgeoning field of nutrition science was using racism as justifications for everything from encouraging assimilation among immigrant groups by decrying their foodways and promoting White Anglo-Saxon Protestant foodways like "traditional" New England and British foods to encouraging "better babies" to save the "White race" from destruction. Nutrition science research with human subjects used almost exclusively adult White men of middle- and upper-middle class backgrounds - usually in college. Certain foods, like cow's milk, were promoted heavily as health food. Notions of purity and cleanliness also influenced negative attitudes about immigrants, African Americans, and rural Americans. During World War II, Progressive-Era-trained nutritionists and nutrition scientists helped usher in a stereotypically New England idea of what "American" food looked like, helping "kill" already declining regional foodways. Nutrition research, bolstered by War Department funds, helped discover and isolate multiple vitamins during this time period. It's also when the first government nutrition guidelines came out - the Basic 7. Throughout both wars, the propaganda was focused almost exclusively on White, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans. Immigrants and African Americans were the target of some campaigns for changing household habits, usually under the guise of assimilation. African Americans were also the target of agricultural propaganda during WWII. Although there was plenty of overt racism during this time period, including lynching, race massacres, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and more, most of the racism in nutrition, nutrition science, and home economics came in two distinct types - White supremacy (that is, the belief that White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values were superior to every other ethnicity, race, and culture) and unconscious bias. So let's look at some of the foundations of modern nutrition science through these lenses. Early Nutrition ScienceNutrition Science as a field is quite young, especially when compared to other sciences. The first nutrients to be isolated were fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fats were the easiest to determine, since fat is visible in animal products and separates easily in liquids like dairy products and plant extracts. The term "protein" was coined in the 1830s. Carbohydrates began to be individually named in the early 19th century, although that term was not coined until the 1860s. Almost immediately, as part of nearly any early nutrition research, was the question of what foods could be substituted "economically" for other foods to feed the poor. This period of nutrition science research coordinated with the Enlightenment and other pushes to discover, through experimentation, the mechanics of the universe. As such, it was largely limited to highly educated, White European men (although even Wikipedia notes criticism of such a Euro-centric approach). As American colleges and universities, especially those driven by the Hatch Act of 1877, expanded into more practical subjects like agriculture, food and nutrition research improved. American scientists were concerned more with practical applications, rather than searching for knowledge for knowledge's sake. They wanted to study plant and animal genetics and nutrition to apply that information on farms. And the study of human nutrition was not only to understand how humans metabolized foods, but also to apply those findings to human health and the economy. But their research was influenced by their own personal biases, conscious and unconscious. The History of Body Mass Index (BMI)Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a result of that same early 19th century time period. It was invented by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet in the 1830s and '40s specifically as a "hack" for determining obesity levels across wide swaths of population, not for individuals. Quetelet was a trained astronomist - the one field where statistical analysis was prevalent. Quetelet used statistics as a research tool, publishing in 1835 a book called Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, the English translation of which is usually called A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. In it, he discusses the use of statistics to determine averages for humanity (mainly, White European men). BMI became part of that statistical analysis. Quetelet named the index after himself - it wasn't until 1972 that researcher Ancel Keys coined the term "Body Mass Index," and as he did so he complained that it was no better or worse than any other relative weight index. Quetelet's work went on to influence several famous people, including Francis Galton, a proponent of social Darwinism and scientific racism who coined the term "eugenics," and Florence Nightingale, who met him in person. As a tool for measuring populations, BMI isn't bad. It can look at statistical height and weight data and give a general idea of the overall health of population. But when it is used as a tool to measure the health of individuals, it becomes extremely flawed and even dangerous. Quetelet had to fudge the math to make the index work, even with broad populations. And his work was based on White European males who he considered "average" and "ideal." Quetelet was not a nutrition scientist or a doctor - this "ideal" was purely subjective, not scientific. Despite numerous calls to abandon its use, the medical community continues to use BMI as a measure of individual health. Because it is a statistical tool not based on actual measures of health, BMI places people with different body types in overweight and obese categories, even if they have relatively low body fat. It can also tell thin people they are healthy, even when other measurements (activity level, nutrition, eating disorders, etc.) are signaling an unhealthy lifestyle. In addition, fatphobia in the medical community (which is also based on outdated ideas, which we'll get to) has vilified subcutaneous fat, which has less impact on overall health and can even improve lifespans. Visceral fat, or the abdominal fat that surrounds your organs, can be more damaging in excess, which is why some scientists and physicians advocate for switching to waist ratio measurements. So how is this racist? Because it was based on White European male averages, it often punishes women and people of color whose genetics do not conform to Quetelet's ideal. For instance, people with higher muscle mass can often be placed in the "overweight" or even "obese" category, simply because BMI uses an overall weight measure and assumes a percentage of it is fat. Tall people and people with broader than "ideal" builds are also not accurately measured. The History of the CalorieAlthough more and more people are moving away from measuring calories as a health indicator, for over 100 years they have reigned as the primary measure of food intake efficiency by nutritionists, doctors, and dieters alike. The calorie is a unit of heat measurement that was originally used to describe the efficiency of steam engines. When Wilbur Olin Atwater began his research into how the human body metabolizes food and produces energy, he used the calorie to measure his findings. His research subjects were the White male students at Wesleyan University, where he was professor. Atwater's research helped popularize the idea of the calorie in broader society, and it became essential learning for nutrition scientists and home economists in the burgeoning field - one of the few scientific avenues of study open to women. Atwater's research helped spur more human trials, usually "Diet Squads" of young middle- and upper-middle-class White men. At the time, many papers and even cookbooks were written about how the working poor could maximize their food budgets for effective nutrition. Socialists and working class unionists alike feared that by calculating the exact number of calories a working man needed to survive, home economists were helping keep working class wages down, by showing that people could live on little or inexpensive food. Calculating the calories of mixed-food dishes like casseroles, stews, pilafs, etc. was deemed too difficult, so "meat and three" meals were emphasized by home economists. Making "American" FoodEfforts to Americanize and assimilate immigrants went into full swing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as increasing numbers of "undesirable" immigrants from Ireland, southern Italy, Greece, the Middle East, China, Eastern Europe (especially Jews), Russia, etc. poured into American cities. Settlement workers and home economists alike tried to Americanize with varying degrees of sensitivity. Some were outright racist, adopting a eugenics mindset, believing and perpetuating racist ideas about criminology, intelligence, sanitation, and health. Others took a more tempered approach, trying to convince immigrants to give up the few things that reminded them of home - especially food. These often engaged in the not-so-subtle art of substitution. For instance, suggesting that because Italian olive oil and butter were expensive, they should be substituted with margarine. Pasta was also expensive and considered to be of dubious nutritional value - oatmeal and bread were "better." A select few realized that immigrant foodways were often nutritionally equivalent or even superior to the typical American diet. But even they often engaged in the types of advice that suggested substituting familiar ingredients with unfamiliar ones. Old ideas about digestion also influenced food advice. Pickled vegetables, spicy foods, and garlic were all incredibly suspect and scorned - all hallmarks of immigrant foodways and pushcart operators in major American cities. The "American" diet advocated by home economists was highly influenced by Anglo-Saxon and New England ideals - beef, butter, white bread, potatoes, whole cow's milk, and refined white sugar were the nutritional superstars of this cuisine. Cooking foods separately with few sauces (except white sauce) was also a hallmark - the "meat and three" that came to dominate most of the 20th century's food advice. Rooted in English foodways, it was easy for other Northern European immigrants to adopt. Although French haute cuisine was increasingly fashionable from the Gilded Age on, it was considered far out of reach of most Americans. French-style sauces used by middle- and lower-class cooks were often deemed suspect - supposedly disguising spoiled meat. Post-Civil War, Yankee New England foodways were promoted as "American" in an attempt to both define American foodways (which reflected the incredibly diverse ecosystems of the United States and its diverse populations) and to unite the country after the Civil War. Sarah Josepha Hale's promotion of Thanksgiving into a national holiday was a big part of the push to define "American" as White and Anglo-Saxon. This push to "Americanize" foodways also neatly ignores or vilifies Indigenous, Asian-American, and African American foodways. "Soul food," "Chinese," and "Mexican" are derided as unhealthy junk food. In fact, both were built on foundations of fresh, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But as people were removed from land and access to land, the they adapted foodways to reflect what was available and what White society valued - meat, dairy, refined flour, etc. Asian food in particular was adapted to suit White palates. We won't even get into the term "ethnic food" and how it implies that anything branded as such isn't "American" (e.g. White). Divorcing foodways from their originators is also hugely problematic. American food has a big cultural appropriation problem, especially when it comes to "Mexican" and "Asian" foods. As late as the mid-2000s, the USDA website had a recipe for "Oriental salad," although it has since disappeared. Instead, we get "Asian Mango Chicken Wraps," and the ingredients of mango, Napa cabbage, and peanut butter are apparently what make this dish "Asian," rather than any reflection of actual foodways from countries in Asia. Milk - The Perfect FoodCombining both nutrition research of the 19th century and also ideas about purity and sanitation, whole cow's milk was deemed by nutrition scientists and home economists to be "the perfect food" - as it contained proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all in one package. Despite issues with sanitation throughout the 19th century (milk wasn't regularly pasteurized until the 1920s), milk became a hallmark of nutrition advice throughout the Progressive Era - advice which continues to this day. Throughout the history of nutritional guidelines in the U.S., milk and dairy products have remained a mainstay. But the preponderance of advice about dairy completely ignores that wide swaths of the population are lactose intolerant, and/or did not historically consume dairy the way Europeans did. Indigenous Americans, and many people of African and Asian descent historically did not consume cow's milk and their bodies often do not process it well. This fact has been capitalized upon by both historic and modern racists, as milk as become a symbol of the alt-right. Even today, the USDA nutrition guidelines continue to recommend at least three servings of dairy per day, an amount that can cause long term health problems in communities that do not historically consume large amounts of dairy. Nutrition Guidelines HistoryBecause Anglo-centric foodways were considered uniquely "American" and also the most wholesome, this style of food persisted in government nutritional guidelines. Government-issued food recommendations and recipes began to be released during the First World War and continued during the Great Depression and World War II. These guidelines and advice generally reinforced the dominant White culture as the most desirable. Vitamins were first discovered as part of research into the causes of what would come to be understood as vitamin deficiencies. Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency), rickets (Vitamin D deficiency), beriberi (Vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency), and pellagra (Vitamin B2 or niacin deficiency) plagued people around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vitamin C was the first to be isolated in 1914. The rest followed in the 1930s and '40s. Vitamin fortification took off during World War II. The Basic 7 guidelines were first released during the war and were based on the recent vitamin research. But they also, consciously or not, reinforced white supremacy through food. Confident that they had solved the mystery of the invisible nutrients necessary for human health, American nutrition scientists turned toward reconfiguring them every which way possible. This is the history that gives us Wonder Bread and fortified breakfast cereals and milk. By divorcing vitamins from the foods in which they naturally occur (foods that were often expensive or scarce), nutrition scientists thought they could use equivalents to maintain a healthy diet. As long as people had access to vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, it didn't matter how they were delivered. Or so they thought. This policy of reducing foods to their nutrients and divorcing food from tradition, culture, and emotion dates back to the Progressive Era and continues to today, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Commodities & NutritionDivorcing food from culture is one government policy Indigenous people understand well. U.S. treaty violations and land grabs led to the reservation system, which forcibly removed Native people from their traditional homelands, divorcing them from their traditional foodways as well. Post-WWII, the government helped stabilize crop prices by purchasing commodity foods for use in a variety of programs operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the National School Lunch Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program. For most of these programs, the government purchases surplus agricultural commodities to help stabilize the market and keep prices from falling. It then distributes the foods to low-income groups as a form of food assistance. Commodity foods distributed through the FDPIR program were generally canned and highly processed - high in fat, salt, and sugar and low in nutrients. This forced reliance on commodity foods combined with generational trauma and poverty led to widespread health disparities among Indigenous groups, including diabetes and obesity. Which is why I was appalled to find this cookbook the other day. Commodity Cooking for Good Health, published by the USDA in 1995 (1995!) is a joke, but it illustrates how pervasive and long-lasting the false equivalency of vitamins and calories can be. The cookbook starts with an outline of the 1992 Food Pyramid, whose base rests on bread, pasta, cereal, and rice. It then goes to outline how many servings of each group Indigenous people should be eating, listing 2-3 servings a day for the dairy category, but then listing only nonfat dry milk, evaporated milk, and processed cheese as the dairy options. In the fruit group, it lists five different fruit juices as servings of fruit. It has a whole chapter on diabetes and weight loss as well as encouraging people to count calories. With the exception of a recipe for fry bread, one for chili, and one for Tohono O'odham corn bread, the remainder of the recipes are extremely European. Even the "Mesa Grande Baked Potatoes" are not, as one would assume from the title, a fun take on baked whole potatoes, but rather a mixture of dehydrated mashed potato flakes, dried onion soup mix, evaporated milk, and cheese. You can read the whole cookbook for yourself, but the fact of the matter is that the USDA is largely responsible for poor health on reservations, not only because it provides the unhealthy commodity foods, but also because it was founded in 1862, the height of the Indian Wars, during attempts by the federal government at genocide and successful land grabs. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the Department of the Interior was largely responsible for the reservation system, the land grant agricultural college system started by the Hatch Act was literally built on the sale of stolen land. In addition, the USDA has a long history of dispossessing Black farmers, an issue that continues to this day through the denial of farm loans. Thanks to redlining, people of color, especially Black people, often live in segregated school districts whose property taxes are inadequate to cover expenses. Many children who attend these schools are low-income, and rely on free or reduced lunch delivered through the National School Lunch Program, which has been used for decades to prop up commodity agriculture. Although school lunch nutrition efforts have improved in recent years, many hot lunches still rely on surplus commodities and provide inadequate nutrition. Issues That PersistEven today, the federal nutrition guidelines, administered by the USDA, emphasize "meat and three" style meals accompanied by dairy. And while the recipe section is diversifying, it is still all-too-often full of Americanized versions of "ethnic" dishes. Many of the dishes are still very meat- and dairy-centric, and short on fresh fruits and vegetables. Some recipes, like this one, seem straight out of 1956. The idea that traditional ingredients should be replaced with "healthy" variations, for instance always replacing white rice with brown rice or, more recently cauliflower rice, continues. Many nutritionists also push the Mediterranean Diet as the healthiest in the world, when in fact it is very similar to other traditional diets around the world where people have access to plenty of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, etc. Even the name - the "Mediterranean Diet," implies the diets of everyone living along the Mediterranean. So why does "Mediterranean" always mean Italian and Greek food, and never Persian, Egyptian, or Tunisian food? (Hint: the answer is racism). Old ideas about nutrition, including emphasis on low-fat foods, "meat and three" style recipes, replacement ingredients (usually poor cauliflower), and artificial sweeteners for diabetics, seem hard to shake for many people. Doctors receive very little training in nutrition and hospital food is horrific, as I saw when my father-in-law was hospitalized for several weeks in 2019. As a diabetic with problems swallowing, pancakes with sugar-free syrup, sugar-free gelatin and pudding, and not much else were their solution to his needs. The modern field of nutritionists is also overwhelmingly White, and racism persists, even towards trained nutritionists of color, much less communities of color struggling with health issues caused by generational trauma, food deserts, poverty, and overwork. Our modern food system has huge structural issues that continue to today. Why is the USDA, which is in charge of promoting agriculture at home and abroad, in charge of federal nutrition programs? Commodity food programs turn vulnerable people into handy props for industrial agriculture and the economy, rather than actually helping vulnerable people. Federal crop subsidies, insurance, and rules assigns way more value to commodity crops than fruits and vegetables. This government support also makes it easy and cheap for food processors to create ultra-processed, shelf-stable, calorie-dense foods for very little money - often for less than the crops cost to produce. This makes it far cheaper for people to eat ultra-processed foods than fresh fruits and vegetables. The federal government also gives money to agriculture promotion organizations that use federal funds to influence American consumers through advertising (remember the "Got Milk?" or "The Incredible, Edible Egg" marketing? That was your taxpayer dollars at work), regardless of whether or not the foods are actually good for Americans. Nutrition science as a field has a serious study replication problem, and an even more serious communications problem. Although scientists themselves usually do not make outrageous claims about their findings, the fact that food is such an essential part of everyday life, and the fact that so many Americans are unsure of what is "healthy" and what isn't, means that the media often capitalizes on new studies to make over-simplified announcements to drive viewership. Key TakeawaysNutrition science IS a science, and new discoveries are being made everyday. But the field as a whole needs to recognize and address the flawed scientific studies and methods of the past, including their racism - conscious or unconscious. Nutrition scientists are expanding their research into the many variables that challenge the research of the Progressive Era, including gut health, environmental factors, and even genetics. But human research is expensive, and test subjects rarely diverse. Nutrition science has a particularly bad study replication problem. If the government wants to get serious about nutrition, it needs to invest in new research with diverse subjects beyond the flawed one-size-fits-all rhetoric. The field of nutrition - including scientists, medical professionals, public health officials, and dieticians - need to get serious about addressing racism in the field. Both their own personal biases, as well as broader institutional and cultural ones. Anyone who is promoting "healthy" foods needs to think long and hard about who their audience is, how they're communicating, and what foods they're branding as "unhealthy" and why. We also need to address the systemic issues in our food system, including agriculture, food processing, subsidies, and more. In particular, the government agencies in charge of nutrition advice and food assistance need to think long and hard about the role of the federal government in promoting human health and what the priorities REALLY are - human health? or the economy? There is no "one size fits all" recommendation for human health. Ever. Especially not when it comes to food. Because nutrition guidelines have problems not just with racism, but also with ableism and economics. Not everyone can digest "healthy" foods, either due to medical issues or medication. Not everyone can get adequate exercise, due to physical, mental, or even economic issues. And I would argue that most Americans are not able to afford the quality and quantity of food they need to be "healthy" by government standards. And that's wrong. Like with human health, there are no easy solutions to these problems. But recognizing that there is a problem is the first step on the path to fixing them. Further ReadingMany of these were cited in the text of the article above, but they are organized here for clarity. I have organized them based on the topics listed above. (note: any books listed below are linked as part of the Amazon Affiliate program - any purchases made from those links will help support The Food Historian's free public articles like this one). EARLY NUTRITION SCIENCE

A HISTORY OF BODY MASS INDEX (BMI)

THE HISTORY OF THE CALORIE

MAKING "AMERICAN" FOOD

MILK - THE PERFECT FOOD

NUTRITION GUIDELINES HISTORY

COMMODITIES AND NUTRITION

ISSUES THAT PERSIST

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

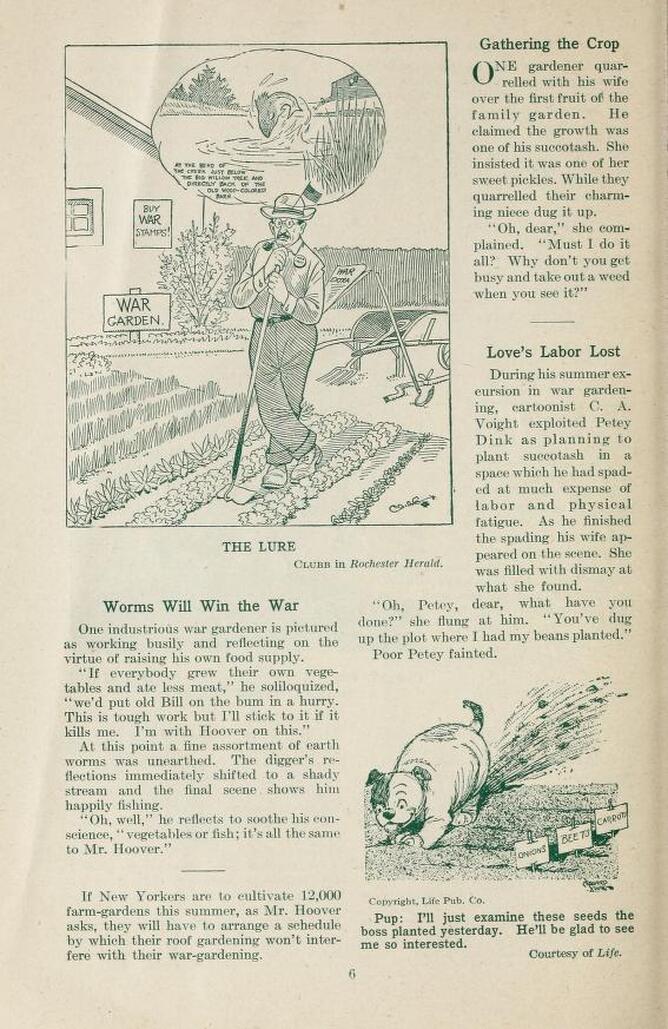

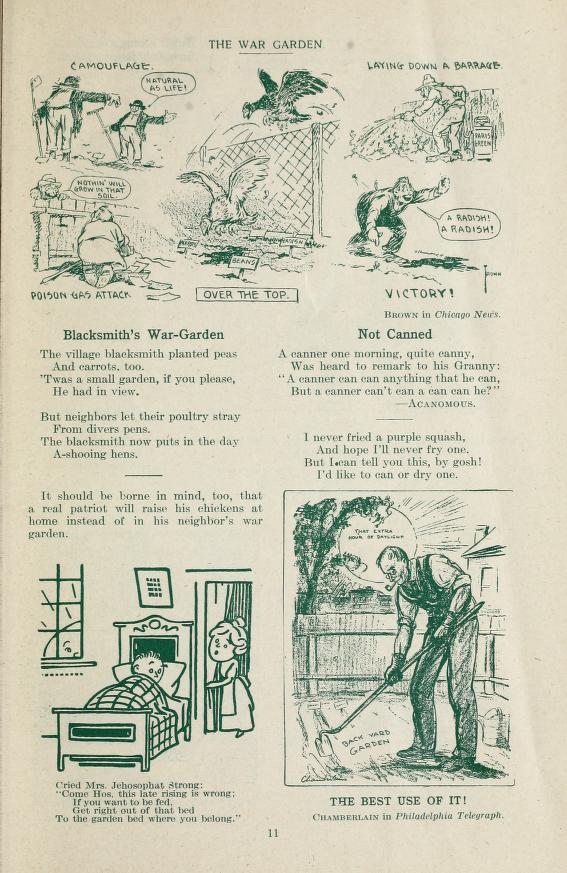

Although literal tons of snow have fallen across the United States in the past week or so, it's still beginning to feel like spring, which for many of us means our thoughts turn to gardening. If you know anything about World War II, you've probably heard of Victory Gardens. But did you know they got their start in the First World War? And the popularity of "war gardens" as they were initially called, is largely thanks to a man named Charles Lathrop Pack. Pack was the heir to a forestry and lumber fortune, and pumped lots of his own money into creating the National War Garden Commission, which promoted war gardening across the country, along with food preservation. They published a number of propaganda posters and instructional pamphlets. Today's World War Wednesday feature is another pamphlet, but its primary audience was not the general public, but rather newspaper and magazine publishers! Full of snippets of poetry, jokes, cartoons, and articles published by newspapers and magazines around the country, even the title was a bit of a joke. "The War Garden Guyed" is a play on the words "guide" and the verb "guy" which means to make fun of, or ridicule. So "The War Garden Guyed" is both a manual to war gardens and also a way to make fun of them. In the introduction, the National War Garden Commission (likely Charles Lathrop Pack himself), writes: "This publication treats of the lighter side of the war garden movement and the canning and drying campaign. Fortunately a national sense of humor makes it possible for the cartoonist and the humorist to weave their gentle laughter into the fabric of food emergency. That they have winged their shafts at the war gardener and the home canner serves only to emphasize the vital value of these activities." Each page of the "guyed" has at least one image and a few bits of either prose or poetry. The below page is one of my favorites. In the upper cartoon, an older man leans on his hoe in a very orderly war garden. His house in the background features a large "War Garden" sign and a poster saying "Buy War Stamps!" In his pocket is a folded newspaper with the headline "War Extra." But he is dreaming of a lake with jumping fish and the caption - indicating the location of the best fishing spot. The cartoon is called "The Lure" and demonstrates how people ordinarily would have been spending their summers. In the lower right hand corner, a roly poly little dog digs frantically in fresh soil. Little signs read "Onions, Beets, Carrots." The caption says "Pup: I'll just examine these seeds the boss planted yesterday. He'll be glad to see me so interested." Another article on the page is titled "Love's Labor Lost." It reads: "During his summer excursion in war gardening, cartoonist C. A. Voight exploited Petey Dink as planning to plant succotash in a space which had had spaded at much expense of labor and physical fatigue. As he finished the spading his wife appeared on the scene. She was filled with dismay at what she found. 'Oh Petey, dear, what have you done?' she flung at him. 'You've dug up the plot where I had my beans planted.' Poor Petey fainted." Many of the bits of doggerel and cartoons poked fun at inexperienced gardeners like Petey Dink. Pests, animals, digging up backyards and hauling water, the difficulty in telling weeds from seedlings, and finally the joy at the first crop. This page has a comic at the top that illustrates these trials and tribulations perfectly, through the lens of war. In the upper left hand corner, a sketch entitled "Camouflage" depicts a man who has just finished putting up a scarecrow who crows, "Natural as life!" as he poses exactly the same as his creation. Below, another called "Poison Gas Attack" depicts a neighbor leaning over the fence to comment "Nothin will grow in that soil" at a man kneeling in the dirt, a bowl of seed packets and a hoe on either side of him. The title implies that the neighbor is full of hot air and poison. The center scene, titled "Over the Top," shows a pair of chickens gleefully flying over a fence to attack a plot marked "Carrots," "Beans," and "Radishes." In the top right-hand corner, in a sketch titled "Laying Down a Barrage," a man with a pump cannister labeled "Paris Green" is spraying his plants. Paris Green was an arsenical pesticide. And finally, in one labeled "Victory!" a man gleefully points to a small seedling in an otherwise empty row and cries, "A radish! A radish!" In a bit of verse called "Not Canned" reads: A canner one morning, quite canny, Was heard to remark to his Granny: "A canner can can anything that he can, But a canner can't can a can can he?" And finally, apt for this past weekend's Daylight Savings Time "spring forward" is an evocative sketch depicts a man hoeing up his back yard garden while a large sun shines brightly and reads "That extra hour of daylight." The sketch is captioned, "The best use of it!" "The War Garden Guyed" has 32 pages of verse, doggerel, short articles, and cartoons. Charles Lathrop Pack was correct when he said the newspapers evoked "gentle laughter" as none of the satirical sheets actually discourage gardening. Indeed, most of the text is directly in line with the propaganda of the day promoting the development of household war gardens and the movement to "put up" produce through home canning and drying. Many of the cartoons directly connect to the war itself, comparing fighting pests to fighting Huns, pesticides to ammunition and "trench gas," and equating canning and food preservation efforts with vanquishing generals. What the booklet does do is poke fun at all of the hardships and difficulties first-time or inexperience gardeners would face. Stray chickens, cabbage worms and potato beetles, dogs and children, competing spouses, naysaying neighbors, post-vacation forests of weeds, and trying desperately to impress coworkers and neighbors with first efforts. War gardens were no easy task, and there were plenty of people who felt that they were a waste of good seed. But Pack and the National War Garden Commission persisted. They believed that inspiring ordinary people to participate in gardening would not only increase the food supply, but also free up railroads for transporting war materiel instead of extra food, get white collar workers some exercise and sunshine, and provide fresh foods in a time of war emergency. How successful the gardens of first-year gardeners were is certainly debatable. But in many ways, war gardens were more about participating than food. After the war, Pack rebranded his "war gardens" as "victory gardens," asking people to continue planting them even in 1919. The idea struck such a chord that when the Second World War rolled around two decades after the first had ended, "victory gardens" and home canning again became a clarion call for ordinary people to participate in the war on the home front. The full "War Garden Guyed" has been digitized and is available online at archive.org. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed