|

During the Second World War, food preservation became a national mandate. I've featured canning-related propaganda posters before, but I thought now would be a good time to feature a few of the lesser-known posters. The above poster is from fairly late in the war. It reads "Grow More, Can More... In '44 - Get your canning supplies now! Jars, Caps and Rings." A special seal featuring a hand (presumably Uncle Sam's) holds a basket containing the words, "Food Fights for Freedom" with "Produce and Conserve" and "Share and Play Square" above. It features a rosy-cheeked young woman in an overtly feminized take on the Women's Land Army overalls, a straw hat tilted fashionably far back on her head, and wearing spotless white work gloves. With a hoe tucked in one elbow and a thumb in her overall strap, she gestures with her free hand at an enormous set of glossy clear glass canning jars, expertly filled with whole tomatoes, halved peaches, green beans, sliced red beets, and what might be whole apricots, yellow plums, or yellow cherries, it's tough to tell. The jars feature a variety of lids, including the new aluminum screw-tops, a glass-topped wire bail with a rubber seal, and a zinc screw top with a rubber seal, illustrating the range of canning technologies still in use. The poster is photorealistic and is probably a literal cut-and-paste of actual photographs - a new technique in an era still dominated by illustrations. It's not clear exactly when this poster was released, but it's likely it was early in the season. The poster exhorts the reader to "grow more" in addition to canning more in 1944, which seems to indicate a spring release, despite the prominence of the large glass canning jars. In addition, the poster warns to stock up on canning supplies now, instead of later in the season. When aluminum was short and factories that made glass were used to produce war materiel, it was easier to make smaller quantities over a longer period of time. By planning ahead, home gardeners and canners could also make sure they had enough supplies on hand to handle an increase in garden produce. Things were getting a bit desperate in 1944 - the war was not going well and the prospect of another long year of war was troubling to ordinary Americans. Rationing had ramped up fully in 1943, and as the war dragged on home canned foods took on more importance in everyday nutrition. For many, especially children, the war must have seemed unending. Little did they know that on June 6, 1944, the United States would launch Operation Overlord - also known as the invasion of Normandy - which would become known as D-Day. D-Day would turn the tide of the war in favor of the Allies, but it would still take another fifteen months for the war to end entirely. Until then, rationing continued and Americans were urged to grow and preserve as much food as they could to supplement their rations. The war finally ended in September of 1945, and by December, rationing of every food except sugar had ended. Foods canned in 1944 would have been important support for rations, but foods canned in 1945 would have been less crucial. One wonders how many home canned foods made it to the end of 1946? We may never know. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join now for as little as $1/month.

Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

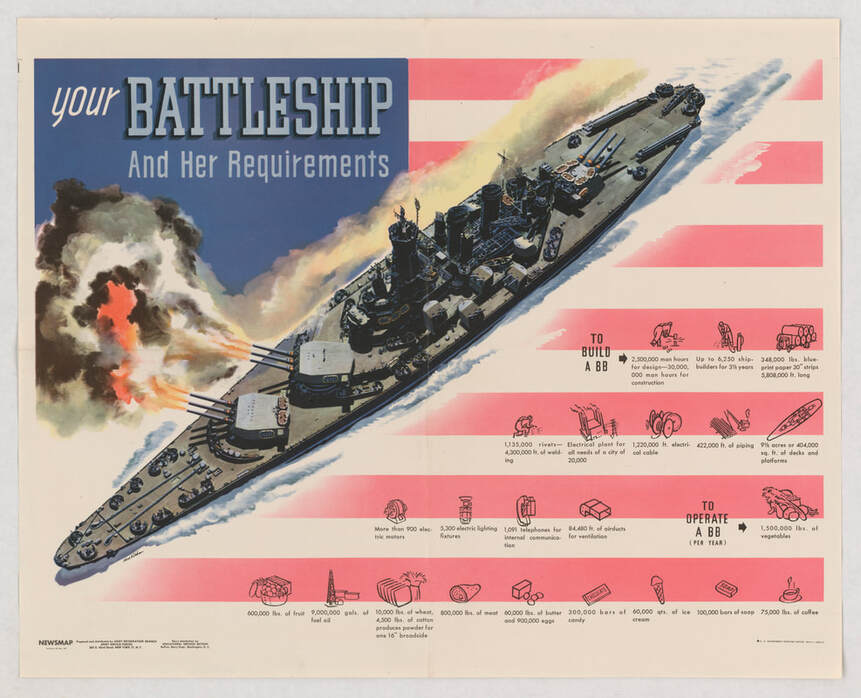

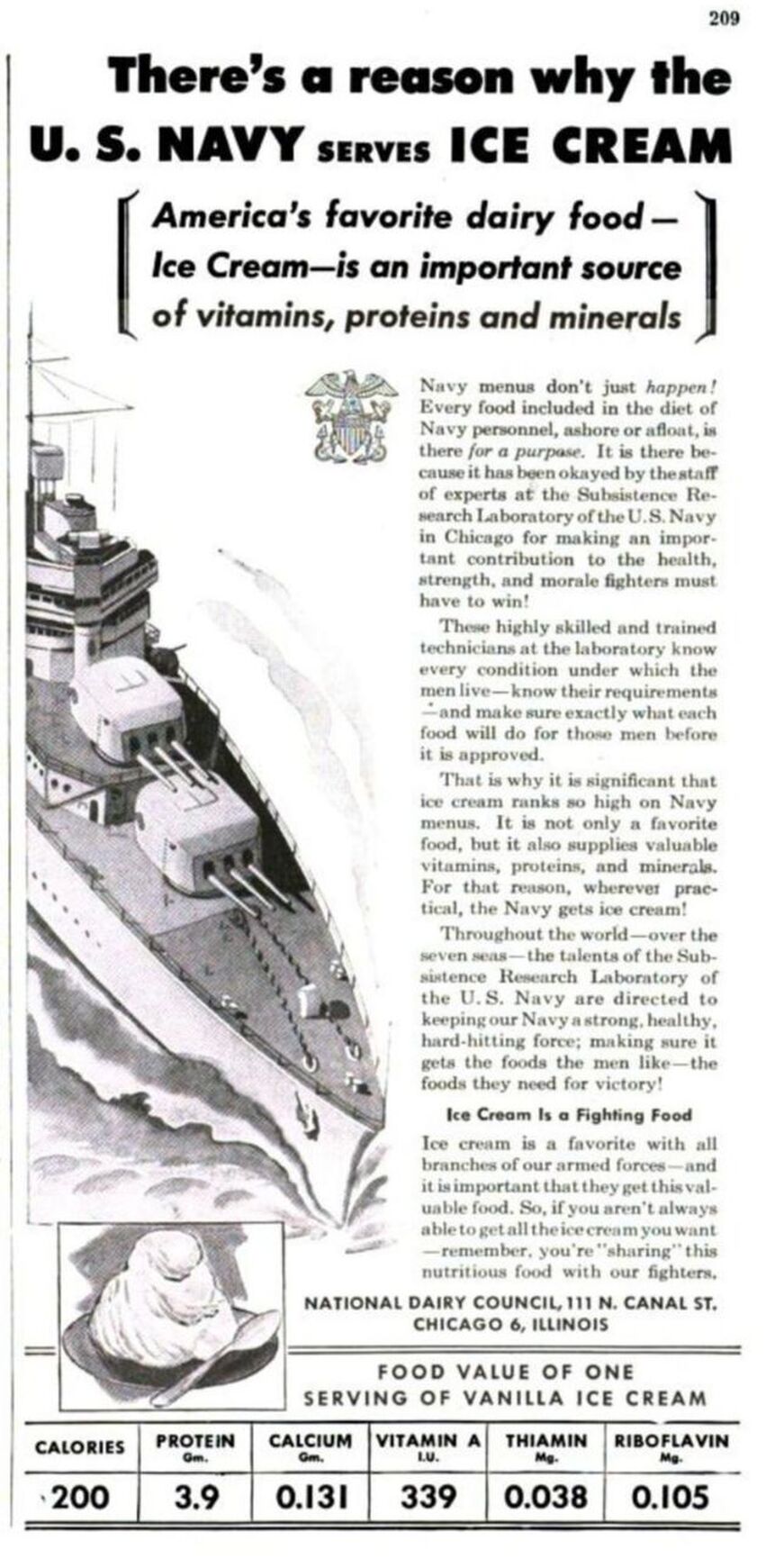

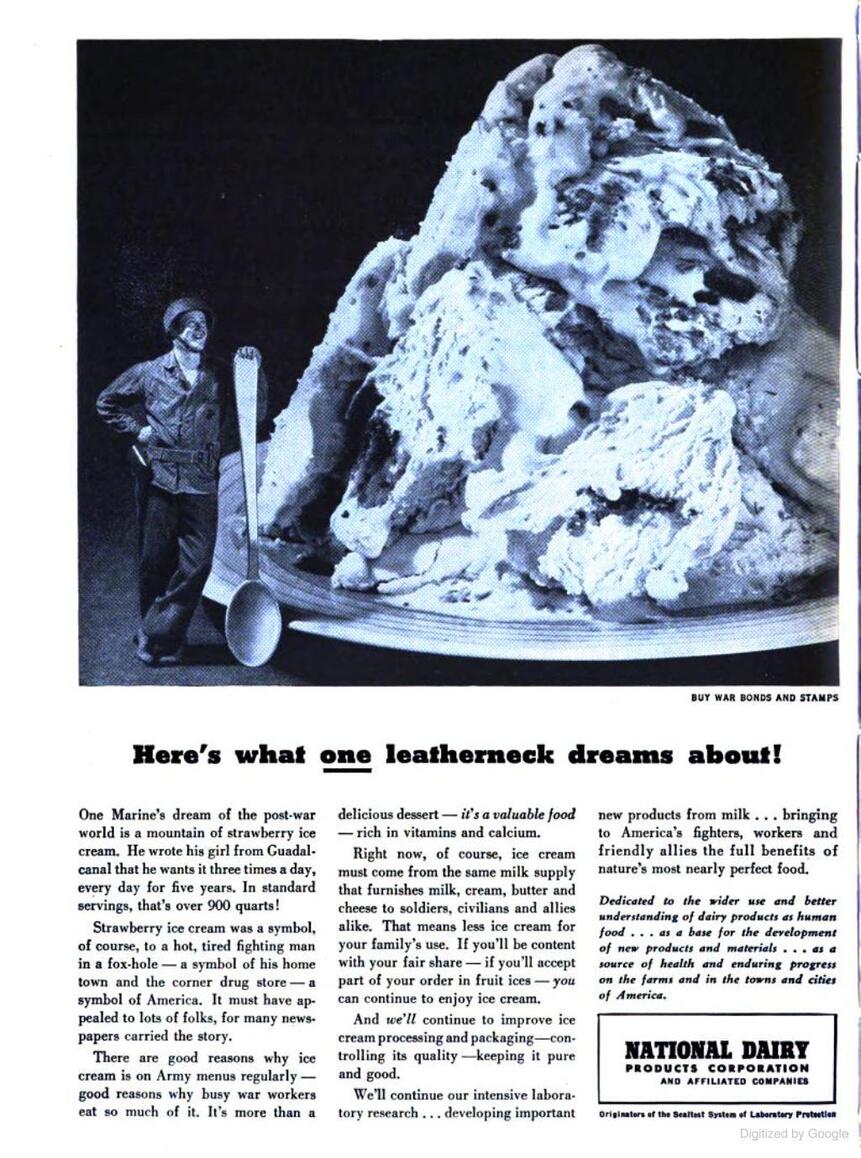

Last World War Wednesday, we looked at the use of ice cream in the U.S. Navy during the First World War, especially aboard hospital ships. Now it's time for a reprise! By the Second World War, ice cream was firmly entrenched aboard Naval vessels. So much so, that battleships and aircraft carriers were actually outfitted with ice cream machinery, and by the end of the war the Navy was training sailors in their uses through special classes. The above propaganda poster, courtesy the National Archives, outlines all of the requirements to build a battleship. "Your Battleship and Her Requirements" may have been targeted toward factory workers, but I think it is more likely this poster was designed to impress upon ordinary Americans the extraordinary amount of materials and supplies needed to keep a battleship in fighting trim. What I found particularly interesting, was that among the supplies listed, alongside fruits and vegetables and meat and even candy, was 60,000 quarts of ice cream! Smaller vessels, such as destroyer escorts and submarines, did not have the space for their own ice cream making machinery, although they did have freezers. In fact, it became common for destroyer escorts and PT boats to rescue downed pilots (the aircraft carries were too big for the job) and "ransom" them for ice cream. Last week a brand new food podcast debuted for American Public Television called "If This Food Could Talk," and I'm so pleased to say I was featured in the first episode, "Frozen in Time: Ice Cream and America's Past." I had a blast doing the research for that episode's interview, which has inspired these two recent World War Wednesday posts. Have a listen if you want to learn more about ice cream in American history, and especially the story of ice cream in the Navy. But while I was doing the research, I kept running across references to ice cream as a health food! The National Dairy Council really leaned into the notion of ice cream and the armed forces. This advertisement reads, "There's a reason why the U.S. Navy serves Ice Cream. America's favorite dairy food - Ice Cream - is an important source of vitamins, proteins and minerals." The ad goes on: "Navy menus don't just happen! Every food included in the diet of Navy personnel, ashore or afloat, is there for a purpose. It is there because it has been okayed by the staff of experts at the Subsistence Research Laboratory of the U.S. Navy in Chicago for making an important contribution to the health, strength, and morale fighters must have to win! "These highly skilled and trained technicians at the laboratory know every condition under which the men live - know their requirements - and make sure exactly what each food will do for those men before it is approved. "That is why it is significant that ice cream ranks so high on Navy menus. It is not only a favorite food, but it also supplies valuable vitamins, proteins, and minerals. For that reason, wherever practical, the Navy gets ice cream! "Throughout the world - over the seven seas - the talents of the Subsistence Research Laboratory of the U.S. Navy are directed to keeping our Navy a strong, healthy, hard-hitting force; making sure it gets the foods the men like - the foods they need for victory! "Ice Cream Is a Fighting Food "Ice cream is a favorite with all branches of our armed forces - and it is important that they get this valuable food. So fi you aren't always able to get all the ice cream you want - remember, you're 'sharing' this nutritious food with our fighters." The National Dairy Council might be just a SMIDGE biased in this regard, but certainly the federal government ranked milk, and by extension milk products, very highly in terms of nutrition during the Second World War, notably as part of the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations. This was almost certainly a holdover from the Progressive Era's take on milk as the "perfect food" - combining proteins, carbohydrates, and fats all in one. We see this in another advertisement, this time by the National Dairy Products Corporation. The National Dairy Council is an industry-funded research and marketing organization. But the National Dairy Products Corporation would later become Kraft Foods. "Here's what one leatherneck dreams about! "One Marine's dream of the post-war world is a mountain of strawberry ice cream. He wrote his girl from Guadalcanal that he wants it three times a day, every day for five years. In standard servings, that's over 900 quarts! "Strawberry ice cream was a symbol, of course, to a hot, tired fighting man in a fox-hole - a symbol of his home town and the corner drug store - a symbol of America. It must have appealed to lots of folks, for many newspapers carried the story. "There are good reasons why ice cream is on Army menus regularly - good reason why busy war workers eat so much of it. It is more than a delicious dessert - it's a valuable food - rich in vitamins and calcium. "Right now, of course, ice cream must come from the same milk supply that furnishes milk, cream, butter and cheese to soldiers, civilians and allies alike. That means less ice cream for your family's use. If you'll be content with your fair share - if you'll accept part of your order in fruit ices - you can continue to enjoy ice cream. "And we'll continue to improve ice cream processing and packaging - controlling its quality - keeping it pure and good. "We'll continue our intensive laboratory research... developing important new products from milk... bringing to America's fighters, workers and friendly allies the full benefits of nature's most nearly perfect food." Here you can see the "perfect food" rhetoric in action! And interestingly, this one touts the role of ice cream in the Army as well. In my opinion ice cream, for all the rhetoric about nutrition, had far more to do with morale than anything else. But there is some truth to the idea that as a dessert it was superior to cake or pie. For one thing, ice cream does have some protein, in addition to a decent amount of fat. Full fat dairy is generally proven to be more filling and satisfying and protein and fat slow down the absorption of sugar directly into the bloodstream, making the "energy-giving" properties of carbohydrates longer-lasting and less likely to make you crash (unlike cake and cookies). That being said, viewing ice cream as a health food is questionable today. But in the period, the discoveries of vitamins and minerals like calcium were cutting-edge, and any food containing those essential nutrients was considered good for you. Ice cream also fit neatly into ideas (unconscious or otherwise) of White supremacy and American (i.e. Anglo-Saxon) culture. As the National Dairy Products Corporation marketing team wrote, ice cream was "a symbol of America." When combined with soda fountains (the wholesome, if sugary, alternative to saloons and beer halls), ice cream seemed to represent the best of America - slim, good-looking, young, White America, that is. Today, ice cream's modern accessibility has given us ice cream alternatives aplenty, especially for folks who can't consume dairy. Ice cream's ubiquity has also meant some of its luster has faded. But at a time of extreme stress - the violence of the theater of war, the privations of home front rationing, the push to mobilize for total war, the fear of invasion - ice cream provided a moment of bliss in the midst of uncertainty. Ice cream is still an essential tradition aboard Naval vessels today. When you're miles from home for months at a time, anything that seems like a treat gives morale a boost. It's still a treasured treat in our household, whether homemade or store bought (if you find yourself in upstate New York - do yourself a favor and seek out Stewart's Shops. They have the best commercial ice cream around). What does ice cream mean to you? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! A special patrons-only post is coming tomorrow with more on ice cream in World War II - this time featuring Elsie the Cow! Join now for as little as $1/month.

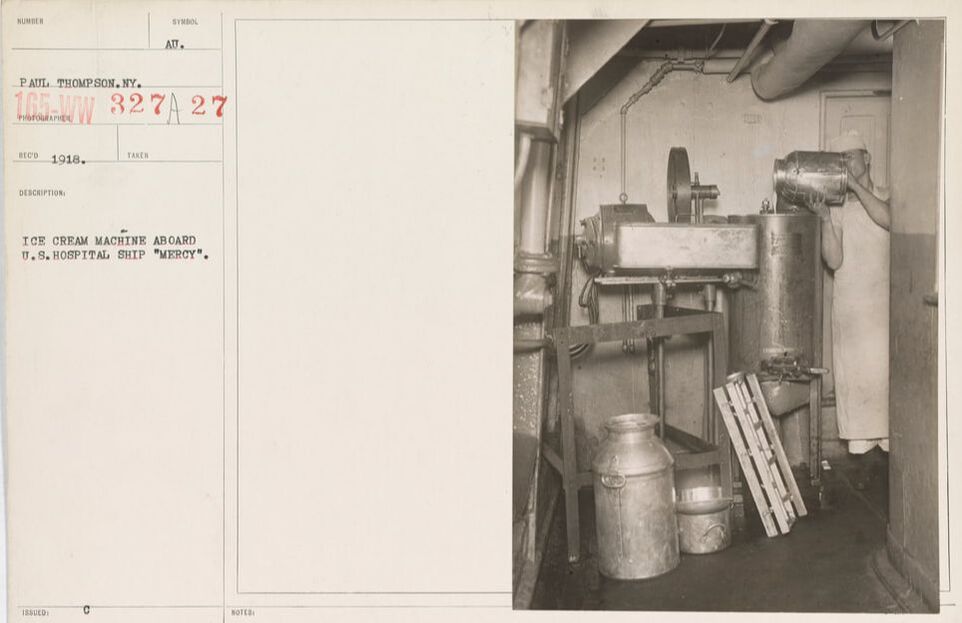

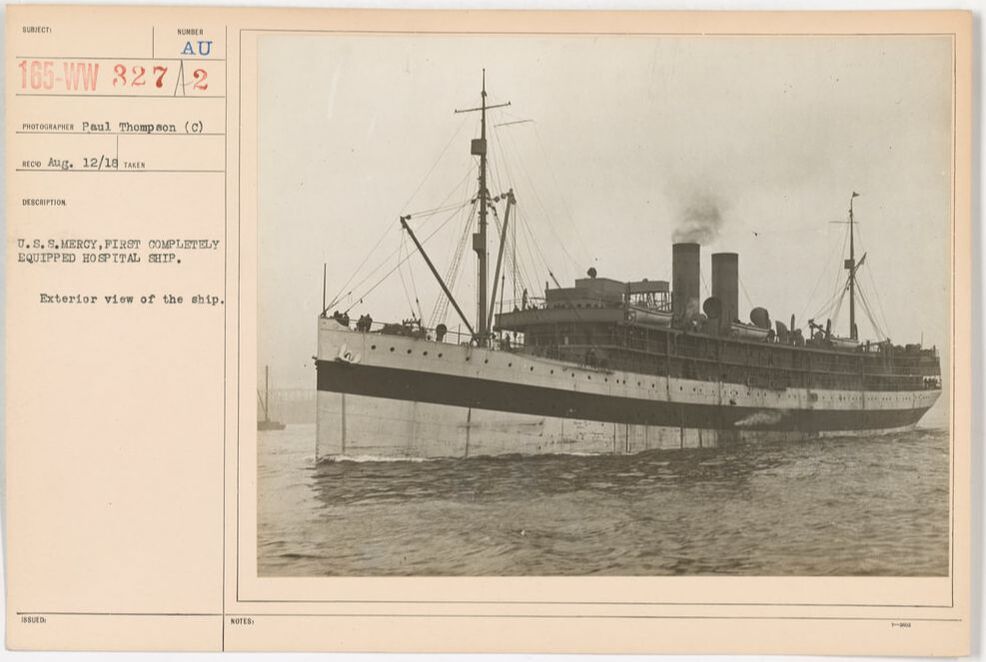

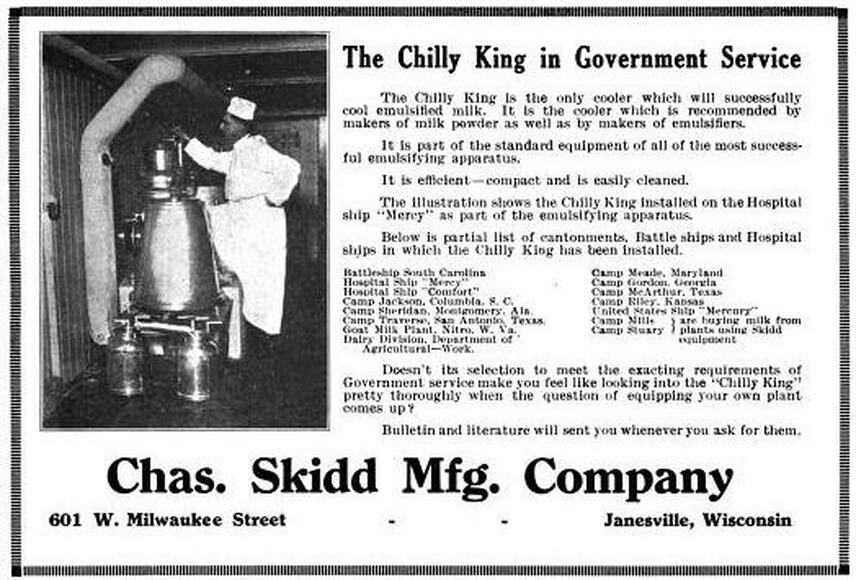

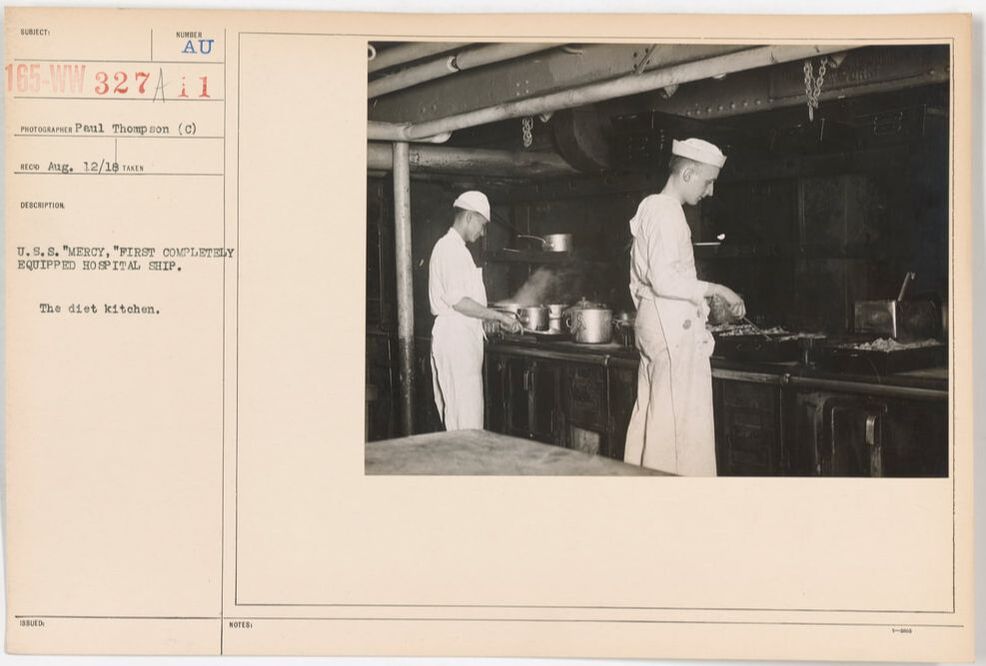

Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! I've been getting a lot of calls for information about ice cream lately, and that has sent me down a rabbit hole. I did a whole talk on the history of ice cream last year (you can watch the filmed version here), but while I knew ice cream was a big tradition in naval history, I didn't know the connection to the First World War. I don't usually cover the history of military consumption of food during the World Wars, but this topic was just too much fun to resist. Ice cream wasn't always the Navy's treat of choice. For over a hundred years rum was the preferred ration by many sailors. But in the late 19th century the Temperance movement began to have increasing power over society. By 1919 we had a Constitutional Amendment (the 19th - often known just as "Prohibition"). But the armed forces went dry much earlier. In particular, on July 1, 1914, the U.S. Navy went alcohol-free. At the same time, naval vessels were being stocked with ice cream. In the May, 1913 issue of The Ice Cream Trade Journal, an article entitled "Sailors Like Ice Cream" explained that the Navy had recently ordered 350,000 pounds of evaporated milk - ostensibly for all sorts of cooking and baking, but ice cream was high on the list. You may wonder why hospital ships in the First World War were manufacturing ice cream on board? Well, it involves multiple factors. First is that ice cream was a product of milk; during the Progressive Era, milk was considered the "perfect food" as it contained fats, proteins, and carbohydrates all in one (supposedly) easily digestible package. Although many people are lactose intolerant, the White Anglo-Saxon dominance of American culture at the time prized milk. Ice cream rode into nutritional value on the coattails of milk. During this time period, dairy-based products like puddings, custards, milk and cream on cooked cereals or with toast, and ice cream were all considered nutritious foods for people who had been injured or ill. Along with foods like beef tea, eggs, and stewed fruits, these made up the bulk of recommended hospital foods from the late 19th century to World War I. Ice cream shows up quite frequently in early reports of the Surgeon General to the U.S. Navy. In his 1918 report to the Secretary of the Navy, ice cream appears to cause more problems than it solves. Notably, the use of ice cream produced commercially results in several instances of crew sickness, including simple illnesses like strep throat, alongside more serious ones like a diphtheria outbreak in Newport in 1917, which was traced to ice cream produced off-station. Fears of the spread of typhoid from places like restaurants, soda fountains, and ice cream shops led to "antityphoid inoculations" at naval shipyards. In Chicago, "All soft-drink and ice-cream stands have promised to give sailors individual service in the form of paper cups and dishes. To make this more effective, it is believed that an order should be issued prohibiting men from accepting any other kind of service." The Surgeon General also recommended inspection of offsite dairies and bottling works for milk, ice cream, and soft drinks to ensure proper sterilization of equipment and pasteurization of dairy products, as well as inoculation of employees against typhoid and smallpox. But ice cream was also noted as essential not only on the existing hospital ship USS Solace, but also on two new hospital ships fitted out since the declaration of war in 1917 - the USS Mercy and the USS Comfort. These ships included a cold storage plant and a refrigerating machine that could "produce, under favorable circumstances, a ton of ice or more a day." The ships also had distilling plants, able to convert seawater to fresh water, up to 20,000 gallons per day. In addition to describing the medical wards, crew facilities, laundry, and kitchen, the report noted: The most valuable adjunct in the treatment and feeding of the sick is the milk emulsifier, popularly known as the "mechanical cow." The milk produced from this machine is made from a combination of unsalted butter and skimmed milk powder and can be made with any proportion of butter fat and proteins desired. This machine will produce 15 gallons of cold, pasteurized milk in 45 minutes. The electric ice cream machine, controlled by one man, makes 10 gallons at a time and is supplemented by small freezers for preparing individual diets for the sick. According to the October, 1918 issue of The Milk Dealer, the "mechanical cow" had been displayed as part of the exhibits at the National Dairy Show in Columbus, Ohio in the fall of 1917. They noted: The "Mechanical Cow" Becoming Famous. Few people who saw the combination exhibit of Merrell-Soule Co. and the DeLaval Separator Co., last October, in Columbus, would have believed that within a year from that beginning the use of the Emulsor in combining Skimmed Milk Powder, unsalted butter and water would be taken up by Army, Navy, City Administrations, etc. throughout the United States. Such is the fact, however. The Mechanical Cow is now producing milk and cream on the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, the two splendid hospital ships of the Navy. An installation on board the U.S.S. South Carolina is kept working continuously to supply the demands of her crew. Mechanical Cows are filling the needs of milk at the base hospitals and several camps and one large machine is being operated by one of the city departments of New York. Health officers, physicians, milk experts and authorities on infant feeding all unanimously agree that milk and cream made by means of the "Mechanical Cow" is superior in every way to the average milk supply. This advertisement for "The Chilly King," a cooling machine that was part of the "Mechanical Cow" system on ships like the U.S.S. Mercy (a photograph of the machinery on board featured in the ad) also names a number of naval ships and military camps which use it, including:

By enabling ships and camps to use shelf-stable skimmed milk powder and unsalted butter, which keeps a very long time in cold storage, "mechanical cows" allowed for an ample supply of milk made in sanitary conditions. For naval ships, this was especially important when crews were away from shore for long periods of time. Ice cream also helped patients recover from illness (or so medical professionals at the time believed) but it also helped a great deal with morale. The professionalization of ship operations via the installation of state-of-the-art equipment was a hallmark of the First World War, but the U.S.'s late involvement in the war hamstrung most shipbuilding operations. Indeed, the construction of a new hospital ship in 1916 was actually shelved in favor of retrofitting existing ships like those that were transformed into the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, which had initially served as the sister passenger steamboats S.S. Havana and S.S. Saratoga, respectively. Part of the Ward Line, these very fast steamships ran the New York City to Havana, Cuba route but were requisitioned in 1917 first as troop transports, and later as hospital ships. The U.S.S. Mercy spent time as a home for the homeless during the Great Depression before she was scrapped in the 1930s, and the U.S.S. Comfort went back to civilian passenger transport for the Ward line under her old name, the S.S. Havana, before being pressed into service again in World War II, this time as a troop transport once again. The names USS Comfort and USS Mercy would be revived in World War II and a third pair of hospital ships bearing those names are still in operation today. Although ice cream is no longer considered central to the recuperation of the sick and wounded, it is still served on American naval vessels around the world. Ice cream would play an even more important role in the Navy during the Second World War. But that's a tale for another World War Wednesday! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

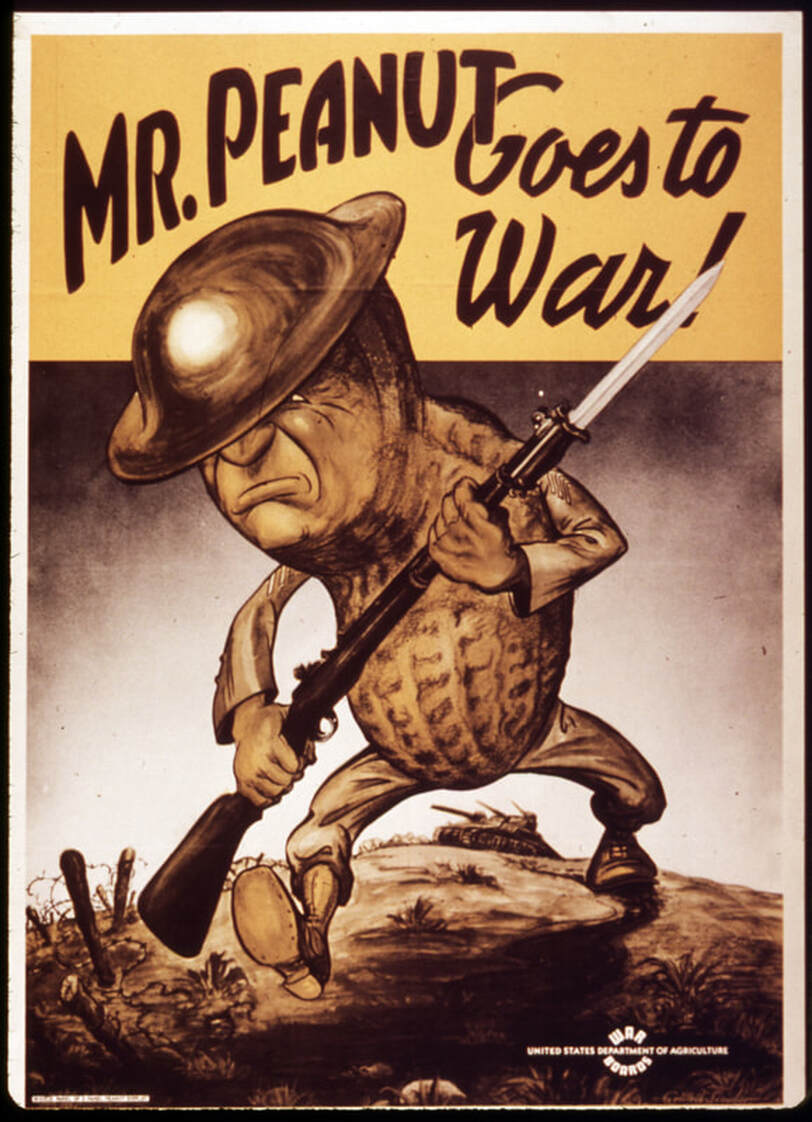

When you think of rationing in World War II, you may not think of peanuts, but they played an outsized role in acting as a substitute for a lot of otherwise tough-to-find foodstuffs, mainly other vegetable fats. When the United States entered the war in December, 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the dynamic of trade in the Pacific changed dramatically. The United States had come to rely on cocoanut oil from the then-American colonial territory of the Philippines and palm oil from Southeast Asia for everything from cooking and the production of foods like margarine to the manufacture of nitroglycerine and soap. Vegetable oils like coconut, palm, and cottonseed were considered cleaner and more sanitary than animal fats, which had previously been the primary ingredient in soap, shortening, and margarine. But when the Pacific Ocean became a theater of war, all but domestic vegetable oils were cut off. Cottonseed was still viable, but it was considered a byproduct of the cotton industry, not an product in and of itself, and therefore difficult to expand production. Soy was growing in importance, but in 1941 production was low. That left a distinctly American legume - the peanut. Peanuts are neither a pea nor a nut, although like peas they are a legume. Unlike peas, the seed pods grow underground, in tough papery shells. Native to the eastern Andes Mountains of South America, they were likely introduced to Europe by the Spanish. European colonizers then also introduced them to Africa and Southeast Asia. In West Africa, peanuts largely replaced a native groundnut in local diets. They were likely imported to North America by enslaved people from West Africa (where peanut production may have prolonged the slave trade). Peanuts became a staple crop in the American South largely as a foodstuff for enslaved people and livestock, but the privations of White middle and upper classes during the American Civil War expanded the consumption of peanuts to all levels of society. Union soldiers encountered peanuts during the war and liked the taste. The association of hot roasted peanuts with traveling circuses in the latter half of the 19th century and their use in candies like peanut brittle also helped improve their reputation. Peanuts are high in protein and fats, and were often used as a meat substitute by vegetarians in the late 19th century. Peanut loaf, peanut soup, and peanut breads were common suggestions, although grains and other legumes still held ultimate sway. George Washington Carver helped popularize peanuts as a crop in the early 20th century. Peanuts are legumes and thus fix nitrogen to the soil. With the cultivation of sweet potatoes, Carver saw peanuts as a way to restore soil depleted by decades of cotton farming, giving Black farmers a way to restore the health of their land while also providing nutritious food for their families and a viable cash crop. During the First World War, peanut production expanded as peanut oil was used to make munitions and peanuts were a recommended ration-friendly food. But it was consumer's love of the flavor and crunch of roasted peanuts that really drove post-war production. By the 1930s, the sale of peanuts had skyrocketed. No longer the niche boiled snack food of Southerners or ground into meal for livestock, peanuts were everywhere. Peanut butter and jelly (and peanut butter and mayonnaise) became popular sandwich fillings during the Great Depression. Roasted peanuts gave popcorn a run for its money at baseball games and other sporting events. Peanut-based candy bars like Baby Ruth and Snickers were skyrocketing in sales. And roasted, salted, shelled peanuts were replacing the more expensive salted almonds at dinner parties and weddings. Peanuts were even included as a "basic crop" in attempts by the federal government to address agricultural price control. They were included in the 1929 Agricultural Marketing Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, and an April, 1941 amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. Peanuts were included in farm loan support and programs to ensure farmers got a share of defense contracts. By the U.S. entry into World War II, most peanuts were being used in the production of peanut butter. And while Americans enjoyed them as a treat, their savory applications were ultimately less popular as an everyday food. But their use as source of high-quality oil was their main selling point during the Second World War. Peanut oil was the primary fuel in Rudolf Diesel's first engine, which debuted in 1900 at the Paris World's Fair. Its very high smoke point has made it a favorite of cooks around the world. During the Second World War peanut oil was used to produce margarine, used in salad dressings and as a butter and lard substitute in cooking and frying. But like other fats, its most important role was in the production of glycerin and nitroglycerine - a primary component in explosives. Which brings us to our imagery in the above propaganda poster. "Mr. Peanut Goes to War!" the poster cries. Produced by the United States Department of Agriculture, it features an anthropomorphized peanut in helmet and fatigues, carrying a rifle, bayonet fixed, marching determinedly across a battlefield, with a tank in the background. Likely aimed at farmers instead of ordinary households, Mr. Peanut of the USDA was nothing like the monocled, top-hatted suave character Planter's introduced in 1916. This Mr. Peanut was tough, determined to do his part, and aid in the war effort. The USDA expected farmers (including African American farmers) to do the same. Further Reading: Note: Amazon purchases from these links help support The Food Historian.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

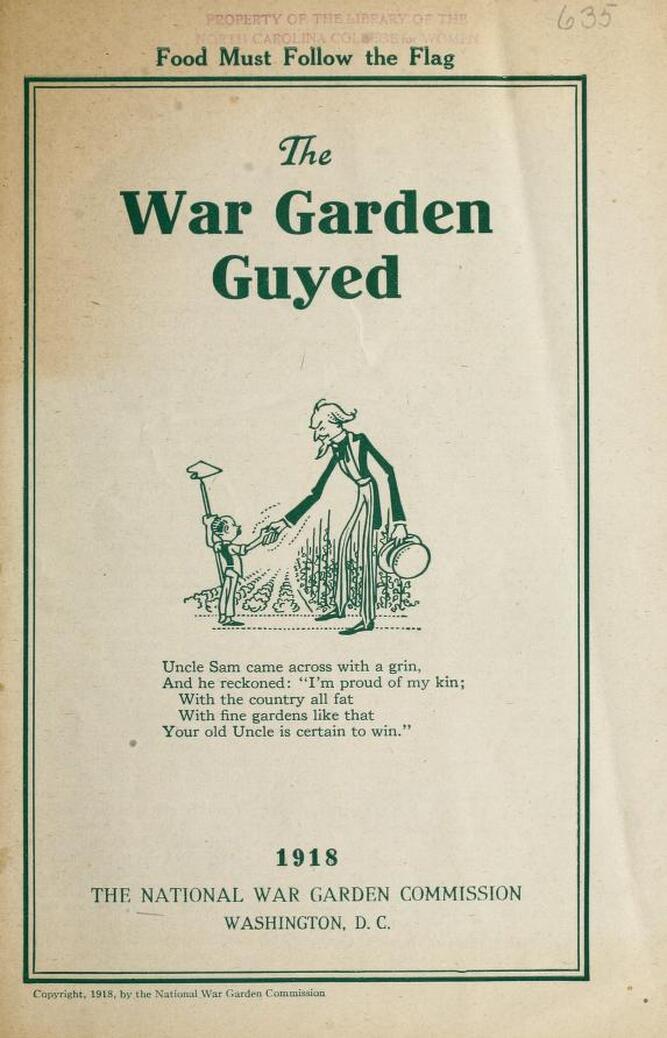

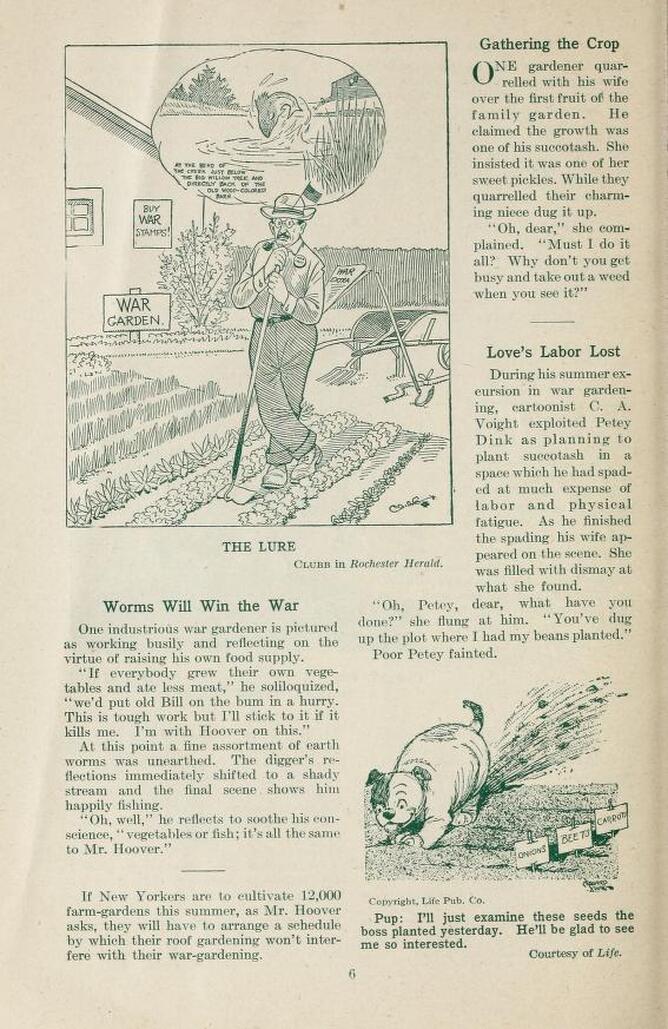

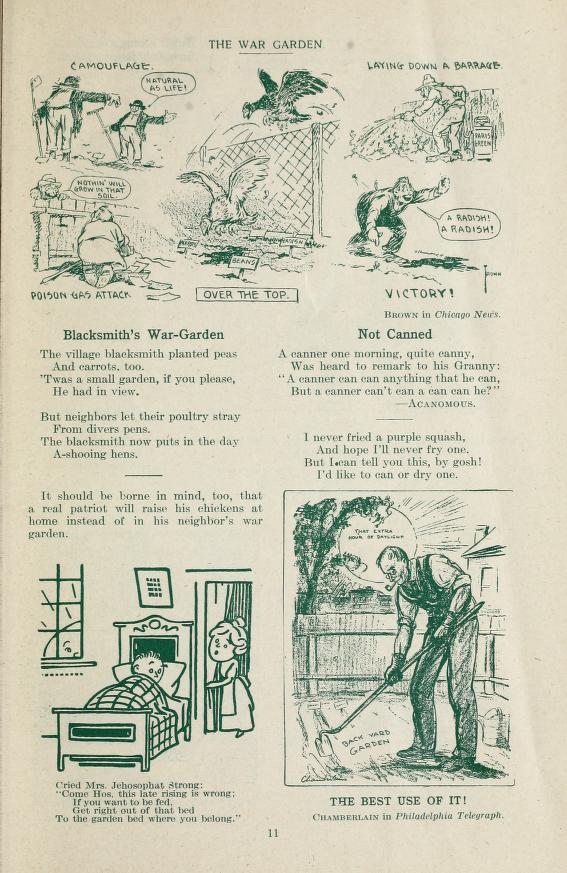

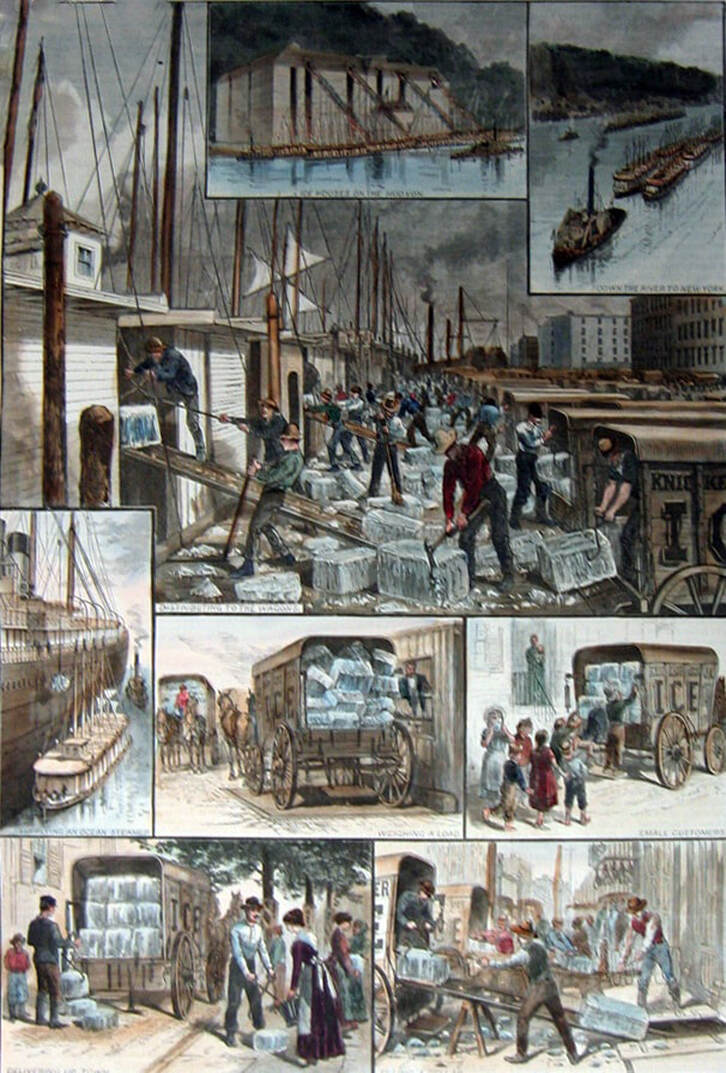

Although literal tons of snow have fallen across the United States in the past week or so, it's still beginning to feel like spring, which for many of us means our thoughts turn to gardening. If you know anything about World War II, you've probably heard of Victory Gardens. But did you know they got their start in the First World War? And the popularity of "war gardens" as they were initially called, is largely thanks to a man named Charles Lathrop Pack. Pack was the heir to a forestry and lumber fortune, and pumped lots of his own money into creating the National War Garden Commission, which promoted war gardening across the country, along with food preservation. They published a number of propaganda posters and instructional pamphlets. Today's World War Wednesday feature is another pamphlet, but its primary audience was not the general public, but rather newspaper and magazine publishers! Full of snippets of poetry, jokes, cartoons, and articles published by newspapers and magazines around the country, even the title was a bit of a joke. "The War Garden Guyed" is a play on the words "guide" and the verb "guy" which means to make fun of, or ridicule. So "The War Garden Guyed" is both a manual to war gardens and also a way to make fun of them. In the introduction, the National War Garden Commission (likely Charles Lathrop Pack himself), writes: "This publication treats of the lighter side of the war garden movement and the canning and drying campaign. Fortunately a national sense of humor makes it possible for the cartoonist and the humorist to weave their gentle laughter into the fabric of food emergency. That they have winged their shafts at the war gardener and the home canner serves only to emphasize the vital value of these activities." Each page of the "guyed" has at least one image and a few bits of either prose or poetry. The below page is one of my favorites. In the upper cartoon, an older man leans on his hoe in a very orderly war garden. His house in the background features a large "War Garden" sign and a poster saying "Buy War Stamps!" In his pocket is a folded newspaper with the headline "War Extra." But he is dreaming of a lake with jumping fish and the caption - indicating the location of the best fishing spot. The cartoon is called "The Lure" and demonstrates how people ordinarily would have been spending their summers. In the lower right hand corner, a roly poly little dog digs frantically in fresh soil. Little signs read "Onions, Beets, Carrots." The caption says "Pup: I'll just examine these seeds the boss planted yesterday. He'll be glad to see me so interested." Another article on the page is titled "Love's Labor Lost." It reads: "During his summer excursion in war gardening, cartoonist C. A. Voight exploited Petey Dink as planning to plant succotash in a space which had had spaded at much expense of labor and physical fatigue. As he finished the spading his wife appeared on the scene. She was filled with dismay at what she found. 'Oh Petey, dear, what have you done?' she flung at him. 'You've dug up the plot where I had my beans planted.' Poor Petey fainted." Many of the bits of doggerel and cartoons poked fun at inexperienced gardeners like Petey Dink. Pests, animals, digging up backyards and hauling water, the difficulty in telling weeds from seedlings, and finally the joy at the first crop. This page has a comic at the top that illustrates these trials and tribulations perfectly, through the lens of war. In the upper left hand corner, a sketch entitled "Camouflage" depicts a man who has just finished putting up a scarecrow who crows, "Natural as life!" as he poses exactly the same as his creation. Below, another called "Poison Gas Attack" depicts a neighbor leaning over the fence to comment "Nothin will grow in that soil" at a man kneeling in the dirt, a bowl of seed packets and a hoe on either side of him. The title implies that the neighbor is full of hot air and poison. The center scene, titled "Over the Top," shows a pair of chickens gleefully flying over a fence to attack a plot marked "Carrots," "Beans," and "Radishes." In the top right-hand corner, in a sketch titled "Laying Down a Barrage," a man with a pump cannister labeled "Paris Green" is spraying his plants. Paris Green was an arsenical pesticide. And finally, in one labeled "Victory!" a man gleefully points to a small seedling in an otherwise empty row and cries, "A radish! A radish!" In a bit of verse called "Not Canned" reads: A canner one morning, quite canny, Was heard to remark to his Granny: "A canner can can anything that he can, But a canner can't can a can can he?" And finally, apt for this past weekend's Daylight Savings Time "spring forward" is an evocative sketch depicts a man hoeing up his back yard garden while a large sun shines brightly and reads "That extra hour of daylight." The sketch is captioned, "The best use of it!" "The War Garden Guyed" has 32 pages of verse, doggerel, short articles, and cartoons. Charles Lathrop Pack was correct when he said the newspapers evoked "gentle laughter" as none of the satirical sheets actually discourage gardening. Indeed, most of the text is directly in line with the propaganda of the day promoting the development of household war gardens and the movement to "put up" produce through home canning and drying. Many of the cartoons directly connect to the war itself, comparing fighting pests to fighting Huns, pesticides to ammunition and "trench gas," and equating canning and food preservation efforts with vanquishing generals. What the booklet does do is poke fun at all of the hardships and difficulties first-time or inexperience gardeners would face. Stray chickens, cabbage worms and potato beetles, dogs and children, competing spouses, naysaying neighbors, post-vacation forests of weeds, and trying desperately to impress coworkers and neighbors with first efforts. War gardens were no easy task, and there were plenty of people who felt that they were a waste of good seed. But Pack and the National War Garden Commission persisted. They believed that inspiring ordinary people to participate in gardening would not only increase the food supply, but also free up railroads for transporting war materiel instead of extra food, get white collar workers some exercise and sunshine, and provide fresh foods in a time of war emergency. How successful the gardens of first-year gardeners were is certainly debatable. But in many ways, war gardens were more about participating than food. After the war, Pack rebranded his "war gardens" as "victory gardens," asking people to continue planting them even in 1919. The idea struck such a chord that when the Second World War rolled around two decades after the first had ended, "victory gardens" and home canning again became a clarion call for ordinary people to participate in the war on the home front. The full "War Garden Guyed" has been digitized and is available online at archive.org. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Last week we talked about the ice harvest during WWI, so I thought this week we would visit this amazing photo you've perhaps seen making the rounds of the internet. Housed at the National Archives, the title reads, "Girls deliver ice. Heavy work that formerly belonged to men only is being done by girls. The ice girls are delivering ice on a route and their work requires brawn as well as the patriotic ambition to help." Two fresh-faced White girls wearing generous overalls and shirts with the sleeves rolled up, their hair tucked under newsboy caps, strain with ice tongs to lift an enormous block of what appears to be natural ice. As the ice appears to be resting on the ground, it's unclear if this photo was posed or not. Large, irregular chunks of ice dot the road beside them, and the open back of an ice wagon is in the background. This photo is a perfect illustration of two major needs of the First World War colliding. One was the huge shift in labor that occurred during the war. With so many men conscripted to the fields of France, it fell to women to enter the workforce, including in fields that typically required "brawn" as well as "patriotic ambition." But while working in fields and factories is understandable to our modern concepts of labor, the idea of ice delivery is maybe not quite so easy to understand. Prior to the 1940s, the majority of Americans refrigerated their foods with ice. If you've ever heard your grandma call the refrigerator an "ice box," she's likely either experienced one, or the term has stayed in usage in her family enough for her to adopt it. An ice box is literally a box in which an enormous block of ice is placed at the top. The cold air and meltwater fall around the container below, in which perishable foods and beverages were placed to keep cool. Although not as cold as modern refrigerators (which hover at around 39-40 degrees F), ice boxes were considerably cooler than cellars and helped prevent meat and dairy products from spoiling, kept vegetables fresh, and even allowed for iced drinks. But, as you can see in the photo, the ice tended to melt fairly quickly. So new ice had to be delivered at least once a week. This colorized illustration from Harper's Weekly shows how the ice was delivered in New York City. It would be taken from enormous ice houses on the Hudson River, storing ice harvested in winter, loaded onto barges, which were towed by steamboats down the Hudson River to New York City, then unloaded from the barges onto shore (or onto transatlantic steamboats) and from shore onto innumerable ice wagons, which would then deliver for commercial or household use. The constant flow of deliveries - sometimes multiple times a day and by competing delivery companies - made for a very inefficient system, especially when it came to labor. Ice was not the only industry using inefficient deliveries - greengrocers, butchers, dry goods salesmen, and milk deliveries also competed with ice for road space and orders. The First World War's impact on labor and the Progressive Era's obsession with efficiency helped to reduce the number of delivery wagons (later trucks) and also the frequency of deliveries, especially to individual households. Nevertheless, efficiency could only go so far. People were still needed to do the labor, and these girls fit the bill. Ice delivery was not a nice trade - it was cold, wet, and often dirty. The work involved endless heavy lifting. Most ice men delivered ice by using the tongs to clamp down on the block (usually a sight smaller than the one they're handling in the photo), and then sling it over his shoulder, resting on a leather pad to protect his shoulder from frostbite. The frequent deliveries to women alone at home inspired jokes (and even songs) similar to the milkman jokes of the 1950s. Perhaps that was why these young women went into the ice trade in 1918? Regardless, the photo was taken in September, 1918, just a few months before Armistice. It is doubtful these young ladies continued in the trade as many women, especially those working in difficult or lucrative jobs, were almost immediately displaced by returning soldiers. I don't know how this photo was used in the period, but perhaps it was used much in the same way we react to it today - applauding the strength and grit of the women who proved they could do the same work as a man.

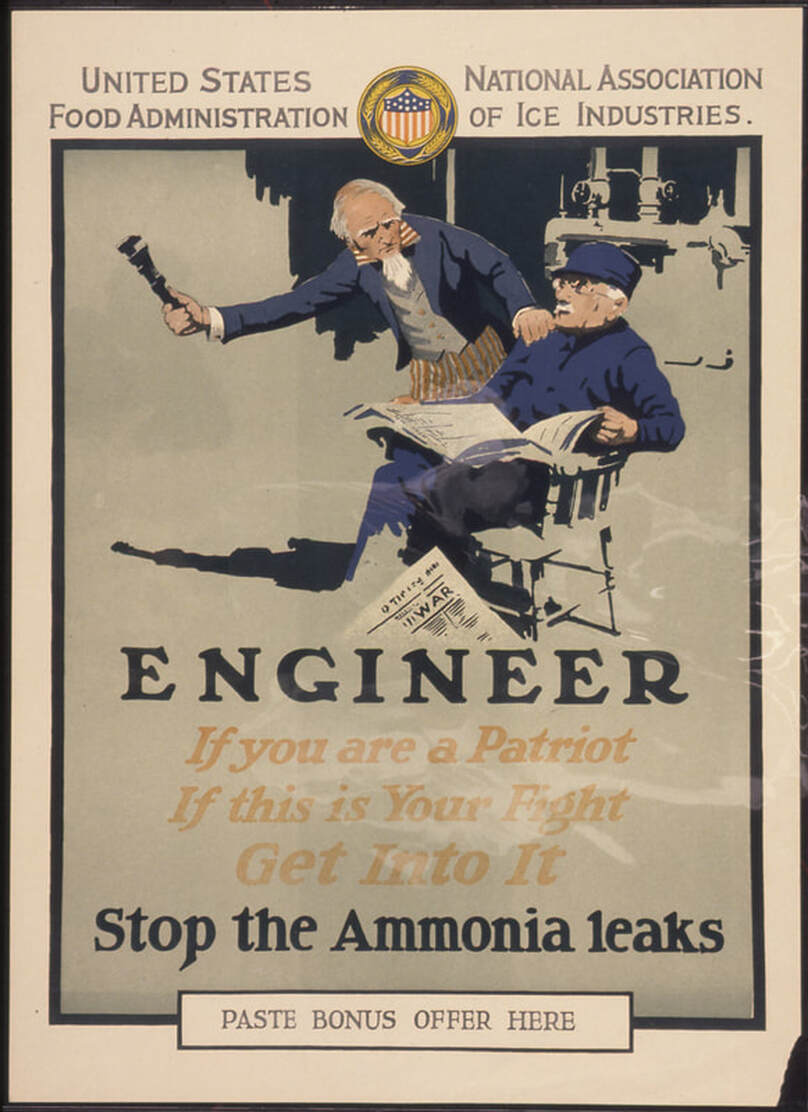

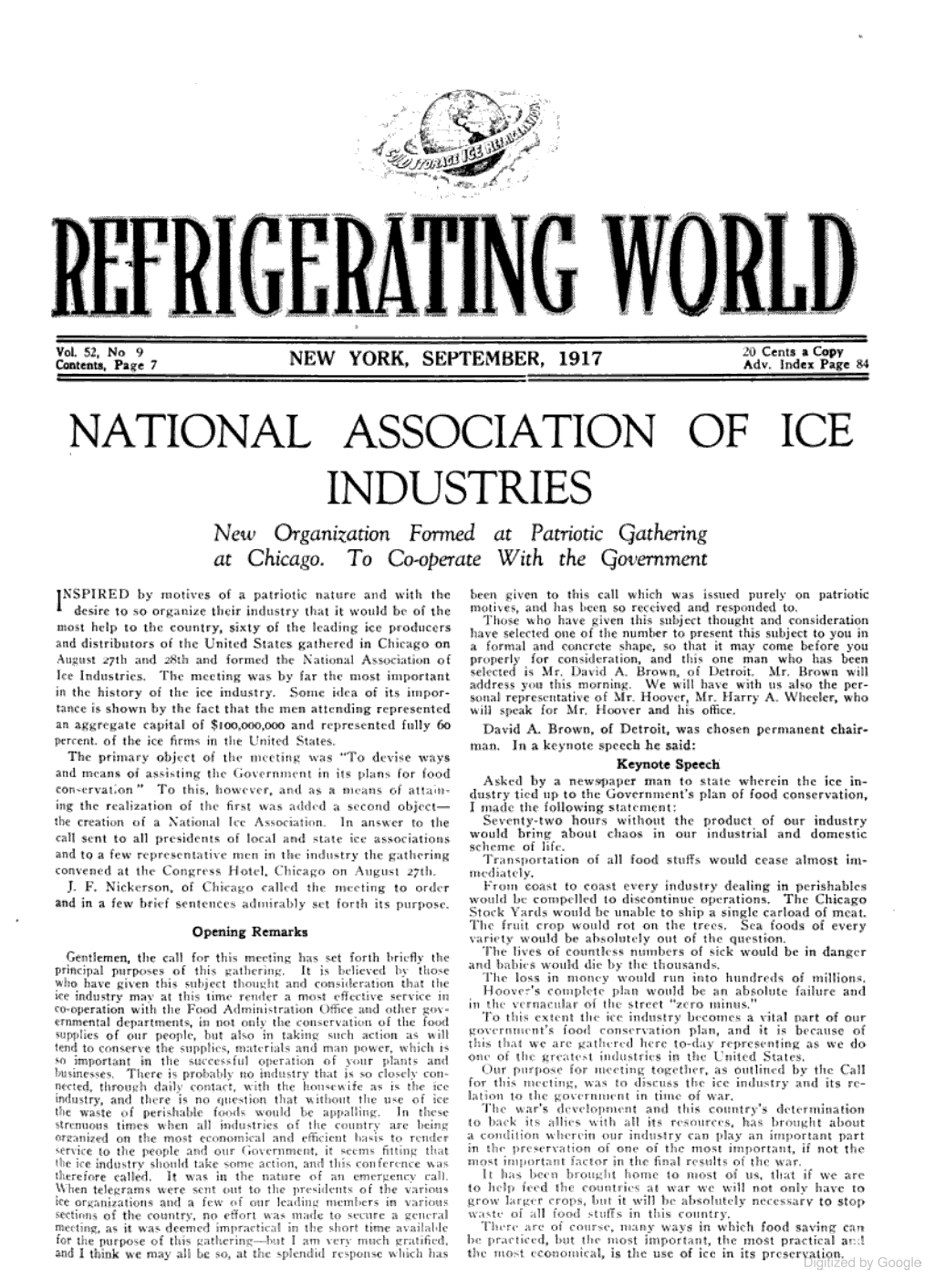

You may be wondering, what on earth do ammonia and engineers have to do with food history? Well, ammonia was one of the primary ingredients in creating artificial ice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The poster above shows Uncle Sam brandishing a wrench, hand on the shoulder of an older engineer, who reclines in a chair reading the newspaper. One sheet of the newspaper has fallen to the floor, and we can make out "War" in the headline. In the background we can see the outlines of pipes and valves. The poster reads "ENGINEER - If you are a patriot, If this is your fight, Get Into It - Stop the Ammonia Leaks." The top of the poster indicates it was sponsored by both the United States Food Administration and the National Association of Ice Industries. Refrigeration was changing rapidly in the 1900s. Most of the country still refrigerated with "natural ice," or ice harvested in winter from freshwater sources like lakes and rivers. But "artificial ice," that is water frozen mechanically, was gaining ground. Artificial ice making factories had been around since the 1870s, but they were costly and inefficient, used primarily in warmer climes where shipping natural ice was too inefficient. The primary refrigerant in these factories was ammonia, which has explosive properties. In fact, ammonia is a primary component in making gunpowder and explosives, and obviously demand for its use went up exponentially when the U.S. joined the First World War in April of 1917. Ammonia cools through compression. Jonathan Reese in Before the Refrigerator: How We Used to Get Ice (Amazon affiliate link) explains the process: The compression refrigeration cycle depends on the compressor forcing a refrigerant around a system of coils. A refrigerant is any substance that can be used to draw heat away from an adjoining space, but some refrigerants worked much better than others. During the late nineteenth century, most American refrigerating machines used ammonia as their refrigerant. The main advantage of ammonia was that it was very efficient. In other words, it has a very low vaporizing temperature (or boiling point) at which it will turn from a liquid into a gas. This means that it required less energy to propel it through the cycle and remove heat from whatever space or substance that the operator needed to become cold. If ammonia leaked through the pipes of these early machines (which it was prone to do), under certain circumstances it could even explode, as the New York packing house example described above illustrates.¹⁰ Most American refrigerating equipment manufacturers didn’t realize that until ammonia compression refrigeration systems had become extremely popular.¹¹ Cold storage also increased in use during the First World War, and refrigerated railroad cars, which helped drive agricultural specialization in fruits and vegetables around the country (Georgia peaches, Florida oranges, Michigan cherries, New York apples, and California's salad bowl), depended on ice for refrigeration and cooling. Ice was the invisible ingredient in the nation's food system. The National Association of Ice Industries was founded in August, 1917 in Chicago, IL as ice harvesters, producers, and distributors gathered at a conference. Realizing the importance of the ice trade in food preservation and conservation, the association vowed to cooperate with the government as part of the war effort. The conference proceedings were reported in Refrigerating World, the industry's trade journal, in the September, 1917 issue. In addition to forming the National Association of Ice Industries on the second day of the conference, the attendees also discussed convincing farmers of the benefits of cold storage and encouraging them to construct ice houses on their farms, of convincing the public that using ice and refrigeration would reduce food waste and save money, and finally of reducing inefficiencies in delivery, including advocating for one delivery service making one delivery per day to prevent competing delivery companies from wasting manpower, horsepower, and ice. Wartime not only necessitated the conservation of ammonia, but also gave the natural ice industry a boost. Already in decline due to concerns about polluted waterways, the natural ice industry was encouraged to revive as another way to conserve ammonia and the fuel that powered the steam engines and electric motors that powered the refrigerating process. The revival would ultimately be short-lived. The end of the First World War all but ended the natural ice industry. As refrigerants became abundant again and energy prices came back down, the demand for artificial ice went up. The advent of electric home refrigerators in the 1920s ultimately signaled the end of the household ice box, and the deliveries that went with it. Read More: The Amazon affiliate links below help support The Food Historian

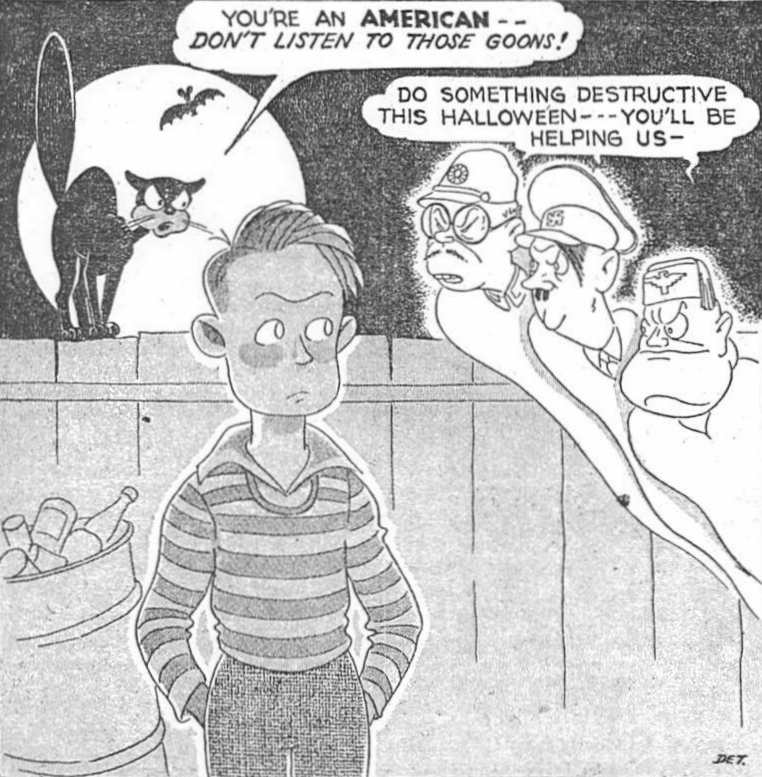

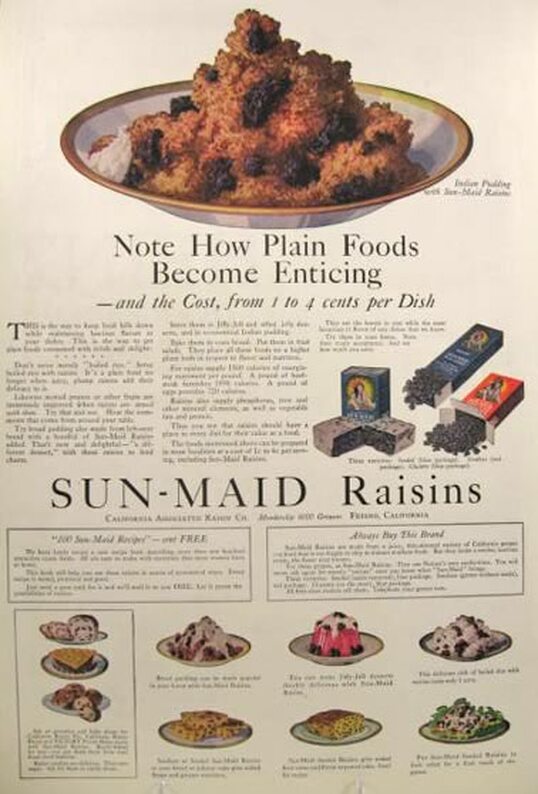

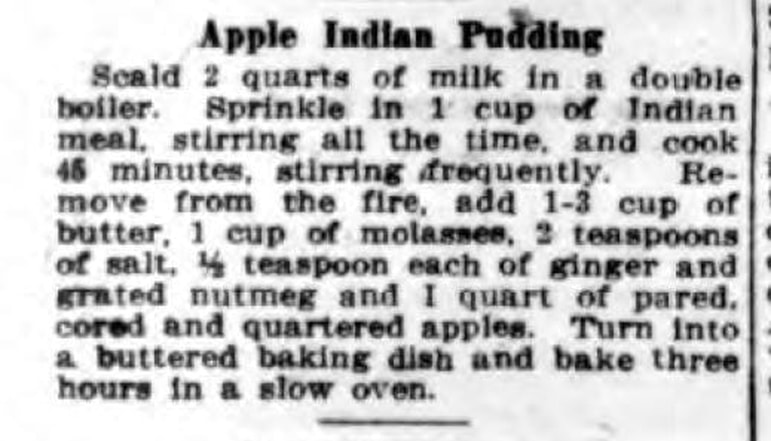

I don't remember when I first encountered "Indian pudding." Derived from the Colonial name for cornmeal - "Indian meal" - it's an iconic dish of New England, though it isn't often made anymore. Combining Indigenous foodways, European cooking techniques, and molasses, a ubiquitous sweetener made cheap by the brutal labor of enslaved Africans, Indian pudding reflected the kind of stick-to-your-ribs cooking common in the Colonial period when people ate less frequently and engaged in harder labor, and with less access to heating than they do today. The above advertisement by Sun-maid Raisins from 1918 is a good illustration of this. "Note How Plain Foods Become Enticing," the ad reads, showing how Indian Pudding could be spiced up with raisins, and then goes on to show just how inexpensive raisins were. Historically, raisins were rather expensive, and had to be stoned (remove the seeds) by hand, a labor-intensive step that continued until the early 20th century. By the time Sun-maid is advertising in 1918, you no longer had to stone raisins - they came seedless. Clearly Sun-maid was trying to convince people that raisins were a more economical purchase than previously believed. Also, the use of Indian Pudding to illustrate the "plain foods" shows how it was viewed by most Americans at that time - plain, cheap, and filling. Indian pudding also fit nicely into rationing suggestions to use less sugar, refined white flour, and fats. With its ingredients of cornmeal and molasses, Indian pudding fit the bill. I first ran across a recipe for Apple Indian Pudding when researching the history of the Farm Cadets in New York State. The article right next to it was about the establishment of the Farm Cadet Corps under the State Military Training commission. Published in the Buffalo Evening News on April 19, 1917, just two weeks after the United States entered the war, it was included as part of a column called "Lucy Lincoln's Talks" and was one of many recipes. Although the United States Food Administration was not yet formed and no rationing recommendations had been issued, President Wilson had been publicly discussing the role of food in the war effort. Throughout the First World War, the United States Food Administration and home economists hearkened back to the Colonial period for several reasons. First, it appealed to Americans' sense of patriotism. Following the American Civil War, Northern reformers made a concerted effort to re-unite the nation and define what it meant to be American. Thanks to the unconscious bias of white supremacy, that idea became closely connected to New England and the mythology around the Pilgrims and the founding of the nation (despite the fact that Spanish Florida, Virginia, parts of Canada, and even New York had been settled earlier). Second, hearkening back to the Colonial period allowed ration supporters to encourage the substitution of non-rationed food items like cornmeal and molasses which had deep Colonial roots, for rationed foods like refined white flour and refined white sugar, which were needed for the war effort. Third, these ingredients were often very inexpensive. By connecting them to the honored founders of the country, food reformers could convince middle and upper class people to eat what may have been previously only associated with the poor and working class, in the name of patriotism. Despite the lack of actual rationing recommendations at this point, the recipe for Apple Indian Pudding would have fit very nicely into the requirements. It used cornmeal, which saved wheat. It used molasses and apples for sweetener, which saved sugar. It used two quarts of milk, which would help use up the milk surplus and add protein. It was also extremely inexpensive and filling, which meant it had appeal for folks on a budget or with large families. The recipe does, however, call for 1/3 cup of butter, which would become one of the recommended ration items in just a few months. Apple Indian Pudding RecipeI have made Indian Pudding before for a talk, and it's lovelier than you'd think. Here's the original recipe: "Scald 2 quarts of milk in a double boiler. Sprinkle in 1 cup of Indian meal, stirring all the time, and cook 45 minutes, stirring frequently. Remove from the fire, add 1/3 cup of butter, 1 cup of molasses, 2 teaspoons of salt, 1/2 teaspoon each of ginger and grated nutmeg, and 1 quart of pared, cored, and quartered apples. Turn into a buttered baking dish and bake three hours in a slow oven." And here's a modern translation: 8 cups (or a half gallon) whole milk 1 cup cornmeal 1/3 cup butter 1 cup molasses 2 teaspoons salt 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon grated fresh nutmeg 3-4 apples Preheat the oven to 300 F. In a double boiler or heavy-bottomed pot, heat the milk, but do not boil. Once hot, slowly whisk in the cornmeal and cook, stirring frequently, for 30-45 mins or until the cornmeal is fully cooked and has absorbed the milk. Remove from heat and while hot, stir in the butter, molasses, salt, and spices. Peel, core, and slice the apples thickly. Stir the apple slices into the cornmeal mixture, and tip it all into a buttered glass or ceramic baking dish. Place in the oven and let bake for 3 hours, uncovered. Serve hot or warm plain (ration-friendly) or with vanilla ice cream or unsweetened liquid cream (not-so ration-friendly). Although the original recipe calls for quartered apples, most modern apples are very large, and a quarter might be too big, which is why I suggest slicing them instead. If you're in an area of the world that gets cold in the fall and winter, Apple Indian Pudding is the perfect, homey dessert to attempt on a day when you'll be puttering around the kitchen or the house all day. Pop some baked beans in with it if you really want a traditional New England supper (and a ration-friendly one!). It really does take three whole hours to bake (other versions included steaming like plum pudding), but the long, slow heat turns the normally crunchy cornmeal into melting softness. There's a reason why it's still so popular in New England. If you want to know more about the history of Indian Pudding, including how to make a historic recipe, check out my lecture below! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month!  Cartoon published in the "San Diego Union," October 25, 1942. Ghosts of Emperor Hirohito of Japan, Adolph Hitler of Germany, and Benito Mussolini say in unison, "Do something destructive this Halloween - you'll be helping us -" to a teenaged boy in an alley. A black cat on the fence behind him says, "You're an AMERICAN - don't listen to those goons!" Trick or treating today is usually about young children, costumes, and lots of candy. In many communities, it's over by 8 or 9 pm. But historically, trick or treating was more about the tricks than the treats. Going door to door threatening tricks if treats were not offered instead is very old, but has deeper roots in association with Christmas than with Halloween. Despite the tradition's age, going door to door for treats on Halloween was not widely practiced in the United States until the 20th century. The pranks, however, were popular among teenaged boys. From the relatively harmless pranks like soaping car windows and placing furniture on porch roofs to the destructive ones like slashing tires, breaking windows, egging houses, and starting fires in the streets, pranks were common in communities across the country. The war changed all that. Halloween, 1942 was the first since the United States entered the war in December, 1941. Across the nation, newspapers published warnings to would-be prankers that destructive acts of the past would no longer be tolerated. This one, published on October 30, 1942 in The Corning Daily Observer in Corning, California, was typical of other messages other newspapers: "Hallowe'en Pranks Are Out For the Duration" "The destructive Hallowe'en pranks of breaking fences, stealing gates, deflating auto tires, ringing door bells to disturb sleepers, soaping windows, and all other forms of the removal or destruction of buildings or property are definitely out and forbidden on Hallowe'en night, according to word from Corning city officials. "Supplies are needed for national defense and are too scarce to permit misuse. "Word comes from Washington that individuals committing such offense shall be prosecuted as saboteurs and be treated accordingly. "Corning officials state that there will be no fooling about this matter this year and anyone contemplating 'having fun' will be treated with severely." The newspaper cartoon above, published in the San Francisco Union on October 25, 1942, illustrates just this sentiment. In it, the ghosts of Japanese Emperor Hirohito, German Chancellor Adolph Hitler, and Italian fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini egg on a young boy hanging out in a dark back alleyway. "Do something destructive this Halloween - - - You'll be helping us - " they tell him. On the high fence behind the boy stands a black cat, back arched in anger, silhouetted by a full moon. He says to the boy, "You're an American - - Don't listen to those goons!" Conflating Halloween pranks with sabotage and aiding the Axis powers was no joke. The November, 1942 newspapers feature stories of pranksters waking sleeping war workers, scaring their neighbors by setting off air raid bells, and causing car accidents by leaving debris in the roads. Several ended up in court, and some got buckshot wounds from angry homeowners for their efforts. Wartime propaganda like this was common - caricatures of the Axis leaders showed up frequently in newspapers, cartoons, and propaganda posters. For Halloween, they made convenient bogeymen. World War II was the beginning of the end of Halloween tricks. Although more innocuous pranks like egging houses and cars and toilet-papering trees and porches continued to be hallmarks of Halloween mischief, the days of fires in the streets, broken windows, and other real crimes were largely in the past. Communities that had previously celebrated Halloween with private parties at home, shifted to more public events like parades, community dances, and trick-or-treating geared toward small children getting treats rather than teenagers engaging in tricks. Further Reading If you'd like to learn more about Halloween during World War II, check out these additional resources:

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Home Halloween parties were extremely popular during the first decades of the 20th century, and although the First World War did slow some of the celebrations, it didn't entirely stop them. On October 28, 1917, the Poughkeepsie Eagle published a full-page spread celebrating Halloween. In it, "Hints for the Hallowe'en Lunch" outlined just how locals could celebrate even with voluntary restrictions on meat, butter, white flour, and sugar. The "Jack-o'-Lantern Salad" features inexpensive salt herring and potatoes, the loaf cake features just one cup of wheat flour with brown sugar and raisins for sweetener, and the "Priscilla Pop Corn" sounds very much like caramel corn! This lunch was likely intended for adult women rather than children, though young women may also have been the intended audience. A composed vegetable salad with sandwiches was typical fare for club women and other ladies who lunched. I've transcribed the whole article below for your reading pleasure. Hints for the Hallowe'en Lunch"Table decorations for a Jack'o'Lantern Jubilee must necessarily include pumpkins big and pumpkins little. Both kinds are introduced into the attractive witches cauldron of the illustration. Its value is increased when an assortment of prophecies is put into the kettle to be distributed to the guests when the strong black coffee is served. "Hallowe'en menus usually include the homely cider and doughnuts, chestnuts and apples which belong to other harvest home celebrations. "The following menu is plain and substantial and just a little different. "Jack-o'-Lantern Menu Jack-o'-Lantern Salad Brown Bread Sandwiches Fruit Loaf Cake Priscilla Pop Corn Cider or Coffee "Jack-o'-Lantern Salad "Soak salt herring in lukewarm water and drain. Cook in boiling water for fifteen minutes. When cool, separate into flakes and add an equal quantity of cold boiled potato, and one-fourth quantity of chopped, hard-boiled eggs. Mix with French dressing [ed. note: vinaigrette] and chill in refrigerator until serving time. Beat one-fourth cupful of cream until stiff and mix with it two tablespoons chopped pimentos. Mix with equal portion of mayonnaise dressing and combine with the salad. Serve on lettuce leaves, slightly flattening the heap on top to receive the "Jack-o'-Lantern," which is a small full moon face cut from a very thin slice of American cheese, the eyes marked with bits of clove, and the nose and mouth by thing strips of pimento. Brown bread sandwiches, with a filling of chopped peanuts is served with this salad. "Raised Fruit Loaf. "One cupful of butter, two cupsful brown sugar, two eggs, two cupsful of bread sponge, two teaspoonsful cinnamon, one teaspoonful clove, two teaspoonsful soda, one teasponful salt, two cupsful raisins, one cupful flour. "Cream butter and add slowly, while beating constantly sugar, then add well-beaten eggs, bread sponge, spice, soda and salt, and flour mixed and sifted, and raisins, cut in half and dredged with flour. Turn into buttered and floured oblong pans and let rise two and one-half hours and then bake for an hour. "Priscilla Popped Corn. "Two quarts of popped corn, two tablespoonsful butter, two cupsful browned sugar, one-half cupful water, one-half teaspoonful salt. Put butter in saucepan, and when melted add sugar, salt and water. Boil sixteen minutes and pour over popped corn, coating each grain thoroughly." What do you think? Would you like to attend such a lunch? I know I would! Even the herring potato salad sounds good and distinctly Scandinavian, although not particularly Halloween-ish. Priscilla popcorn, however, is definitely going on the to-make list! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed