|

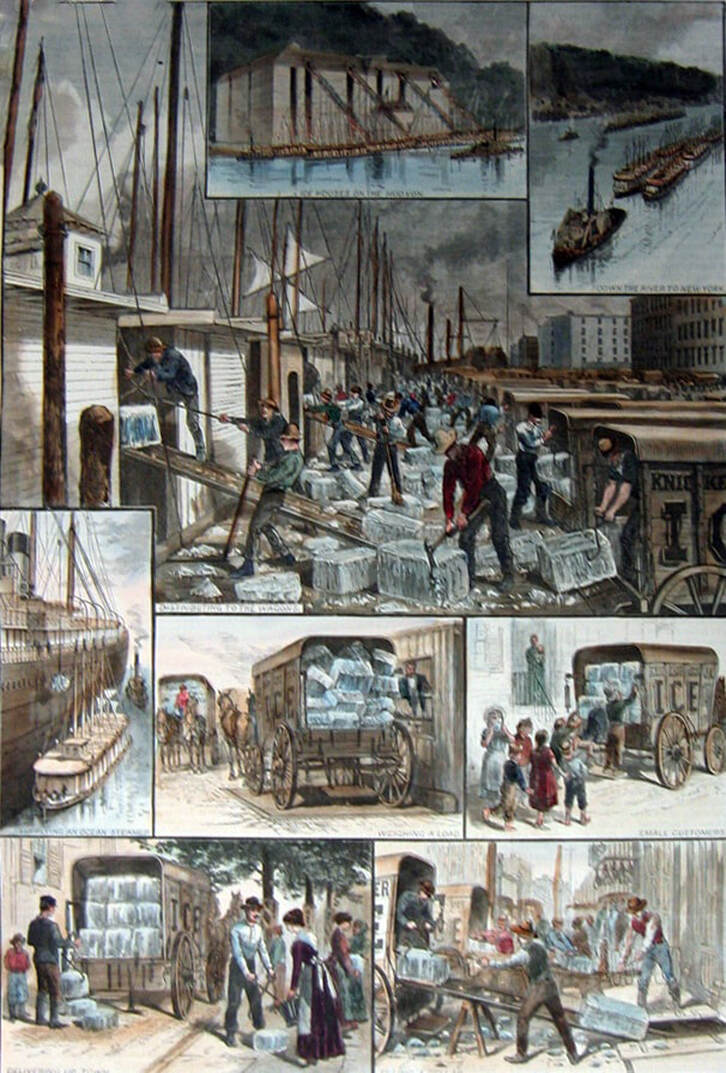

Last week we talked about the ice harvest during WWI, so I thought this week we would visit this amazing photo you've perhaps seen making the rounds of the internet. Housed at the National Archives, the title reads, "Girls deliver ice. Heavy work that formerly belonged to men only is being done by girls. The ice girls are delivering ice on a route and their work requires brawn as well as the patriotic ambition to help." Two fresh-faced White girls wearing generous overalls and shirts with the sleeves rolled up, their hair tucked under newsboy caps, strain with ice tongs to lift an enormous block of what appears to be natural ice. As the ice appears to be resting on the ground, it's unclear if this photo was posed or not. Large, irregular chunks of ice dot the road beside them, and the open back of an ice wagon is in the background. This photo is a perfect illustration of two major needs of the First World War colliding. One was the huge shift in labor that occurred during the war. With so many men conscripted to the fields of France, it fell to women to enter the workforce, including in fields that typically required "brawn" as well as "patriotic ambition." But while working in fields and factories is understandable to our modern concepts of labor, the idea of ice delivery is maybe not quite so easy to understand. Prior to the 1940s, the majority of Americans refrigerated their foods with ice. If you've ever heard your grandma call the refrigerator an "ice box," she's likely either experienced one, or the term has stayed in usage in her family enough for her to adopt it. An ice box is literally a box in which an enormous block of ice is placed at the top. The cold air and meltwater fall around the container below, in which perishable foods and beverages were placed to keep cool. Although not as cold as modern refrigerators (which hover at around 39-40 degrees F), ice boxes were considerably cooler than cellars and helped prevent meat and dairy products from spoiling, kept vegetables fresh, and even allowed for iced drinks. But, as you can see in the photo, the ice tended to melt fairly quickly. So new ice had to be delivered at least once a week. This colorized illustration from Harper's Weekly shows how the ice was delivered in New York City. It would be taken from enormous ice houses on the Hudson River, storing ice harvested in winter, loaded onto barges, which were towed by steamboats down the Hudson River to New York City, then unloaded from the barges onto shore (or onto transatlantic steamboats) and from shore onto innumerable ice wagons, which would then deliver for commercial or household use. The constant flow of deliveries - sometimes multiple times a day and by competing delivery companies - made for a very inefficient system, especially when it came to labor. Ice was not the only industry using inefficient deliveries - greengrocers, butchers, dry goods salesmen, and milk deliveries also competed with ice for road space and orders. The First World War's impact on labor and the Progressive Era's obsession with efficiency helped to reduce the number of delivery wagons (later trucks) and also the frequency of deliveries, especially to individual households. Nevertheless, efficiency could only go so far. People were still needed to do the labor, and these girls fit the bill. Ice delivery was not a nice trade - it was cold, wet, and often dirty. The work involved endless heavy lifting. Most ice men delivered ice by using the tongs to clamp down on the block (usually a sight smaller than the one they're handling in the photo), and then sling it over his shoulder, resting on a leather pad to protect his shoulder from frostbite. The frequent deliveries to women alone at home inspired jokes (and even songs) similar to the milkman jokes of the 1950s. Perhaps that was why these young women went into the ice trade in 1918? Regardless, the photo was taken in September, 1918, just a few months before Armistice. It is doubtful these young ladies continued in the trade as many women, especially those working in difficult or lucrative jobs, were almost immediately displaced by returning soldiers. I don't know how this photo was used in the period, but perhaps it was used much in the same way we react to it today - applauding the strength and grit of the women who proved they could do the same work as a man.

0 Comments

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed