|

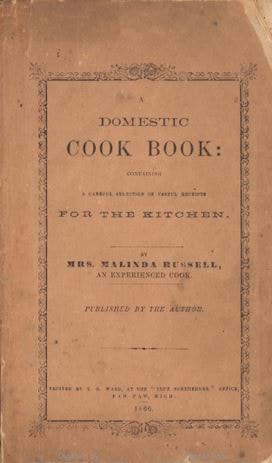

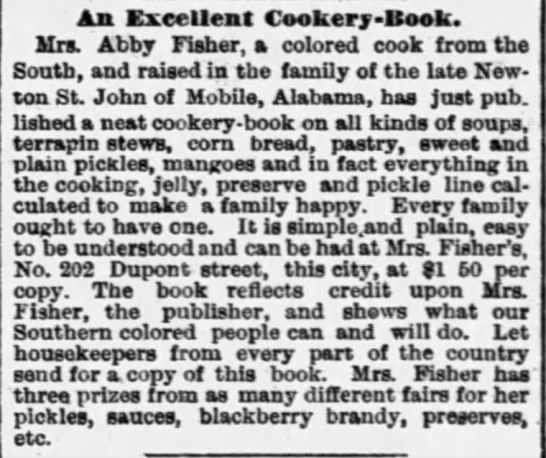

Throughout the 19th century, white women used their domestic assets to pick up the slack left by disabled or deceased husbands - homes became boarding houses and tea rooms and domestic skills were translated into magazine articles and cookbooks. But free Black women in the 19th century did not have as many assets. And even when they did, these assets were often taken from them, and a racist and sexist judicial system gave them little recourse to recover property. Enslaved women freed by the Emancipation Proclamation had their freedom, but little else. The promised 40 acres and a mule never materialized. Despite these often difficult starts, many free and formerly enslaved women of color used their wits and skills to make their own way in the world. Often relegated to service jobs in households, many women created their own small businesses to avoid working for wages - tea rooms, boarding houses, laundries, seamstress and millinery shops, catering, etc. Most of these jobs had low startup costs and could be done from home, allowing for the care of children and family members. Many women also worked as professional cooks for taverns and hotels, a job that held more promise of profit and respect than working in a private household. The vast majority of women working in these fields remain hidden from history - unnamed and un-written-about. But some women of color have managed to make their mark on food history. Here are a few of their stories. Anne Northup - Twelve Years AloneAnne Northup was my first real encounter with the stories of adversity and perseverance many Black women faced throughout the 19th century. I attended a special program at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City with a historic dinner recreated by The Food Griot - Tonya Hopkins. Anne Hampton was born in 1808 in upstate New York. A free woman of color, she married Solomon Northup in the 1820s and in 1834 they sold their farm and moved to Saratoga. Solomon often worked as a fiddler and Anne worked as a cook and kitchen manager at hotels in the spa resort town. She was working at the Pavilion Hotel in Saratoga when she met wealthy white New Yorker Eliza Jumel in 1841. Divorcee/widow of Aaron Burr, Madame Jumel convinced Anne to come south and serve as a cook in her household. Anne sent her eldest daughter Elizabeth to Manhattan with Jumel, but waited until later in the year to come south herself, likely finishing out the busy tourist season. Earlier that summer of 1841, Anne's husband Solomon had answered an advertisement looking for musicians for a job in Virginia. An accomplished violinist, Solomon had answered the advertisement and traveled south. He was captured and sold into slavery, spending the next twelve years enduring brutal conditions on a Louisiana sugar plantation. Anne was left to fend on her own. After a year in Eliza Jumel's household, Anne and some (but not all) of her children returned to Saratoga, where they stayed until 1850, when they moved to Glens Falls and Anne continued her hotel work. They were not reunited with Solomon until 1853. He wrote a book about his experiences - Twelve Years a Slave. We lose track of Solomon Northup in the 1860s and his death date is unknown, although Anne and her children continue to live in New York. To learn more about the Northup family, read this excellent account by historian David Fiske. Anne Northup died on August 8, 1876 in Moreau, New York. Although she leaves behind no documentation of the food she cooked, given her positions in fashionable resort town hotels and wealthy households, she was likely very skilled in a variety of foodways. To me, she represents how many free women of color made their way in the world on the strength of their cooking skills, even in the face of extraordinary adversity. Malinda Russell & Her Union PrinciplesIn 2000, Jan Longone ran across a slim, crumbling cookbook wrapped in brown paper at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where she is curator of American culinary history. That cookbook, A Domestic Cookbook, published in 1866 by a woman named Malinda Russell, turned out to be the earliest known cookbook published by an African American woman. The cookbook has since been digitized, and when I read it for the first time the other day, I was struck by the incredible hardship Russell had to overcome in her life. In the autobiographical account that explains why she wrote the cookbook, Russell recounted the many setbacks in her life. Born free in Tennessee, at age 19 she set out to emigrate to Liberia, a promise of life free from the racism and oppression that continued to plague free Black communities in the North. But along the way, she was robbed by someone from her party, and was forced to stay in Virginia, where she made a living as a cook and a nurse. There, she married Anderson Vaughn, and they had a son together, but Vaughn died just four years later, leaving Russell a widow with a handicapped son. She moved back to Tennessee and opened a boarding house in a town that featured springs as a tourist attraction. She later opened a pastry shop in that same down and had saved up a sum of money to support herself and her son. But in early 1864, she was attacked and robbed by a "guerrilla party," likely Confederate soldiers. She and her son fled Tennessee during the height of the Civil War. Although Tennessee was a Union state, its proximity to the border meant it was not safe for Russell. She made her way to Michigan, enduring several attacks along the way, and went on to start over, again, in a new state. In May, 1866, she published A Domestic Cookbook. She closed her introduction stating that she hoped the sale of the cookbook would help her raise funds to return to Tennessee and reclaim some of her lost property when peace was restored. We do not know if she ever made it home to Tennessee, or really much else about her at all, although Jan Longone has worked to find more about her. According to Russell herself, "I have learned my trade of Fanny Steward, a colored cook, of Virginia, and have since learned many new things in cooking." She also indicated her cookbook was organized along the lines of Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife (1824). Malinda Russell reset much of the conventional wisdom about Black cooking heritage at the time it was rediscovered. But her cookbook is not much different from any other cookbook of the period - reflecting her experience as a boarding house owner and cook, cooking for the public and likely for audiences diverse in race and socioeconomic status. It also knows its audience, consisting largely of dessert and preserves recipes. These were commonly featured in published cookbooks because they were more complex than the everyday cooking of meat and vegetables and less likely to be familiar to ordinary cooks. Her cookbook contains everything from the humble "Baked Indian Meal Pudding" and 'Sliced Sweet Potato Pie," to the exquisite "Floating Islands" and "Charlotte Russe." For me, the most striking thing about Russell is not the content of her cookbook, but rather the fact that it exists at all - a testament to her difficult life and the grit she used to persevere. What Abby Fisher Knew "Pickles and Fruit. The purest home-made Pickles and Preserves of all kinds, put up in the good old Southern style. A liberal discount to the trade. Address, Mrs. Abbey Fisher and Husband, 569 Howard St. San Francisco." Advertisement from the December 13, 1879 issue of "The Placer Herald," published in Rocklin, CA. Unlike Anne Northup and Malinda Russell, Abby Clifton was born into slavery in 1831 in South Carolina to a white father and an enslaved mother. It is unclear when gained her freedom, but by 1860 she had moved to Alabama and married Albert Fisher. In 1877, they emigrated to California and by 1880, Abby and Albert were in San Francisco, where the 1880 Census listed Abby as a "cook" and Albert as a pickle and preserve manufacturer. But this attribution was likely due to sexism common among census takers. In reality, it was Abby who was manufacturing pickles and preserves - as listed in an 1882 San Francisco directory. Albert was listed as a porter. Abby leveraged her expertise in pickles and preserves to reach the highest echelons of San Francisco society. She was awarded a diploma at 1879 Sacramento State Fair. At the 1880 San Francisco Mechanics Institute Fair, she won a bronze medal for her pickles and preserves. Although she and Albert could not read or write, in 1881 she published the cookbook, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. with assistance from white friends who helped her translate and transcribe her memorized recipes into cookbook format. The book does not contain just pickles and preserves, although they and her famous blackberry cordial certainly make a showing. The title inclusion of "Old Southern Cooking" is certainly apt, given recipes for "Maryland Beat Biscuit," "Plantation Corn Bread," "Ochra Gumbo," "Creole Chow Chow," "Sweet Potato Pie," and "Peach Cobbler." But it also includes typical British-American foods popular in the Northeast and throughout the United States, including "Sally Lund" bread, "Jumble" cookies, "Sauce for Suet Pudding," "Rhubarb Pie," (rhubarb grows poorly in the South, needing below freezing temperatures), three different kinds of "Sherbet," "Yorkshire Pudding," and "Terrapin Soup." In short, her cooking is more representative of broad American style cooking of the period, with some Southern flavor, rather than stereotypically "Southern" (i.e. Black) cooking. The interest in Southern cooking, as evidenced by the marketing of her book, was likely part of a reaction to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Historian Megan Elias has written about "Lost Cause cookbooks" in which white Americans romanticized the "good old days" of slavery and subservient Black folks with "magic" cooking skills. It is possible that Abby Fisher's cookbook was swept up in the wave of racist nostalgia. But it is also possible that Abby's cookbook was simply a reflection of the interest in California residents in the cuisines of many newly arrived emigrants of all cultures and backgrounds. This seems to be the case in one announcement, published in the San Francisco Examiner on July 11, 1881. It reads: "An Excellent Cookery-Book. "Mrs. Abby Fisher, a colored cook from the south, and raised in the family of the late Newton St. John of Mobile, Alabamaa, has just published a neat cookery-book on all kinds of soups, terrapin stews, corn bread, pastry, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes and in fact everything in the cooking, jelly, preserve and pickle line calculated to make a family happy. Every family ought to have one. It is simple and plain, easy to be understood and can be had at Mrs. Fisher's, No. 202 Dupont street, this city, at $1.50 per copy. The book reflects credit upon Mrs. Fisher, the publisher, and shows what our Southern colored people can and will do. Let housekeepers from every part of the country send for a copy of this book. Mrs. Fisher has three prizes from as many different fairs for her pickles, sauces, blackberry brandy, preserves, etc." Although we may never know how many copies Abby sold, the cookbook seemed to garner positive reviews. For several weeks in 1881, she (or the publisher) advertised it in the Oakland Tribune (see below).  "Mrs. Abby Fisher's, Southern Cookery book on soups, terrapin stews, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes, preserves, corn bread; price $1.50; 202 Dupont st., San Francisco. jy11-1m." Advertisement for Mrs. Fisher's cookbook in the "Oakland Tribune," published July 11, 1881, but running for several weeks prior and after. In the 1890 San Francisco directory, "Mrs. Abbie Fisher" was still listed as "mnfr. pickles and preserves," but it is unclear what happened after that. Her exact death date is also unknown. No known obituary was published. After the Great San Francisco Fire of 1907, reference to Abby and her cookbook all but disappeared until a copy surfaced in 1984 at a Sotheby's auction in New York City. The Schlesinger Library purchased it and at the time it was thought to be the first cookbook published in the United States by a Black woman, until Malinda Russell toppled Abby from her throne in 2000. Like Malinda and Anne, Abby used her cooking skills to make her own way in the world - supporting her family and showcasing her talents. Ghosts in the KitchenOf course, we know about these women because they left a written record. We know about Anne through her husband Solomon and his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave and the records of Eliza Jumel. We know about Malinda because of her cookbook and the autobiography she includes in it. And we know about Abby because of her cookbook and her existence in newspapers and city directories. But there were tens of thousands of women of color making their own way on the strength of their culinary skills, just like these women, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Ashbell McElveen called James Hemings the "ghost in America's kitchen," but he wasn't the only one. Enslaved women and men shaped American food profoundly. And women of color - enslaved, freed, and born free - left their mark as well. Because I know how history works, I am hopeful that more records and cookbooks of cooks of color - published or not - will continue to show up in the coming decades. And when they do, I know they'll help us better understand how our food got to be the way it is, and where it can go in the future. Further ReadingAnne Northup:

Malinda Russell:

Abby Fisher:

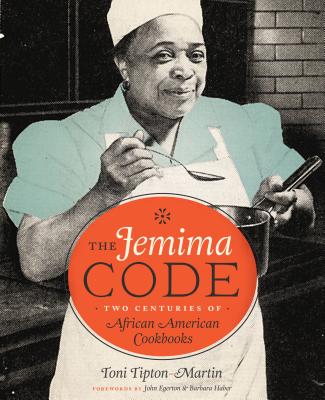

The Jemima CodeThe Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, Toni Tipton Martin. University of Texas Press, 2015. ISBN 0292745486. This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. If you want to know more about African American cookbooks, I recommend Toni Tipton Martin's The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. Although the information for each entry is sadly quite brief, it is nonetheless an important, enlightening, and beautifully produced catalog of all the known cookbooks authored by African Americans (real and fictional) in the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

0 Comments

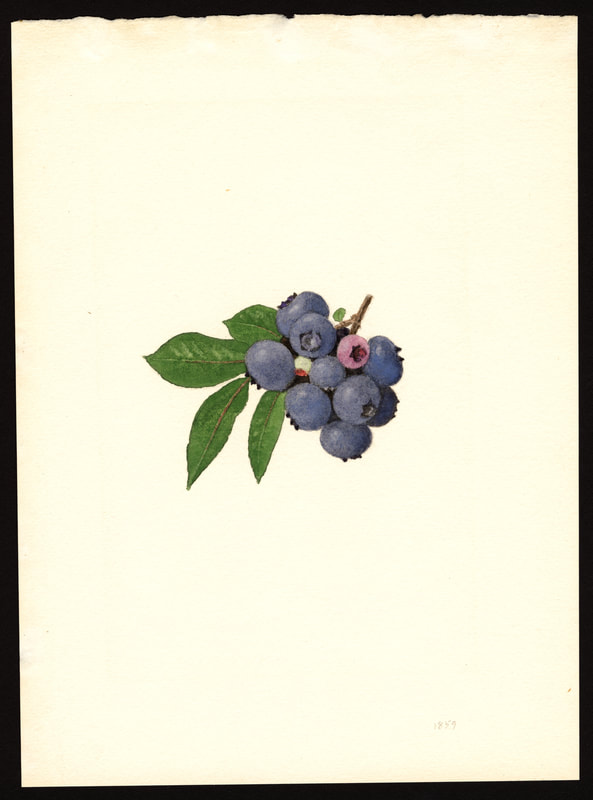

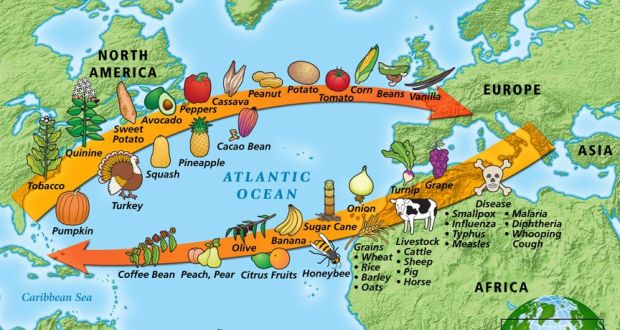

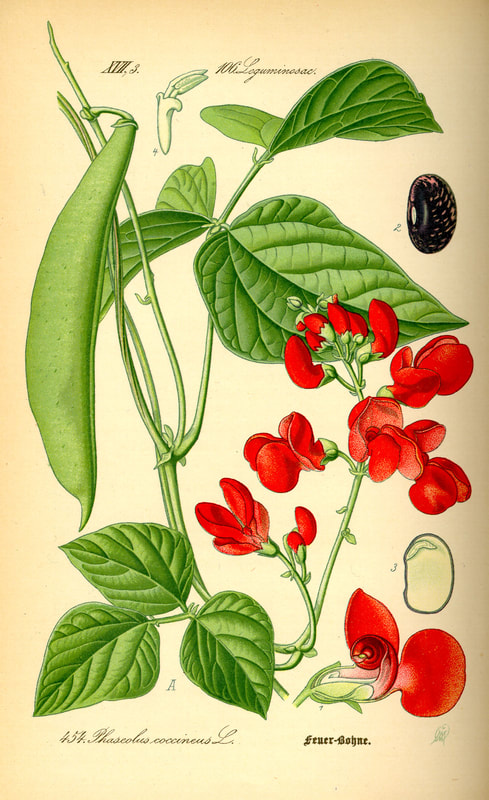

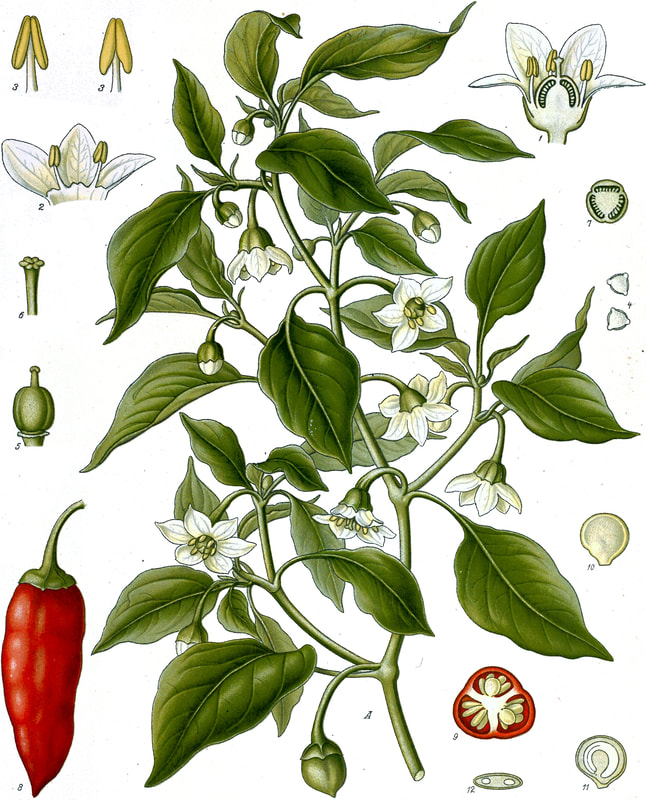

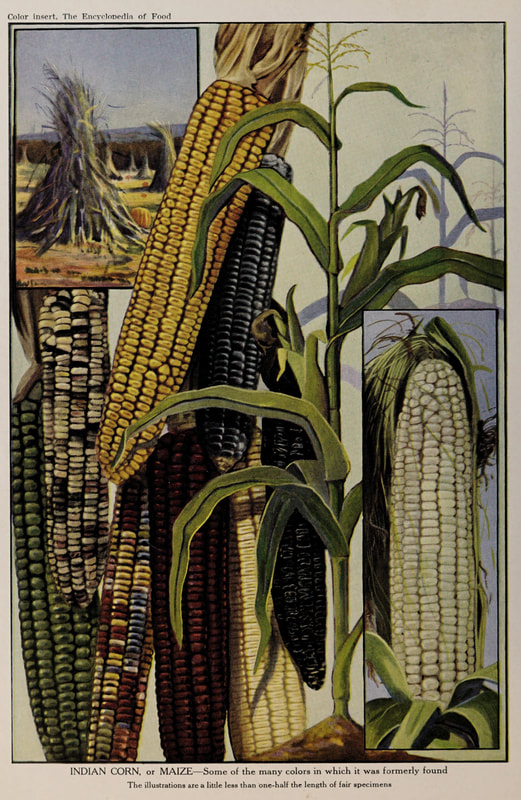

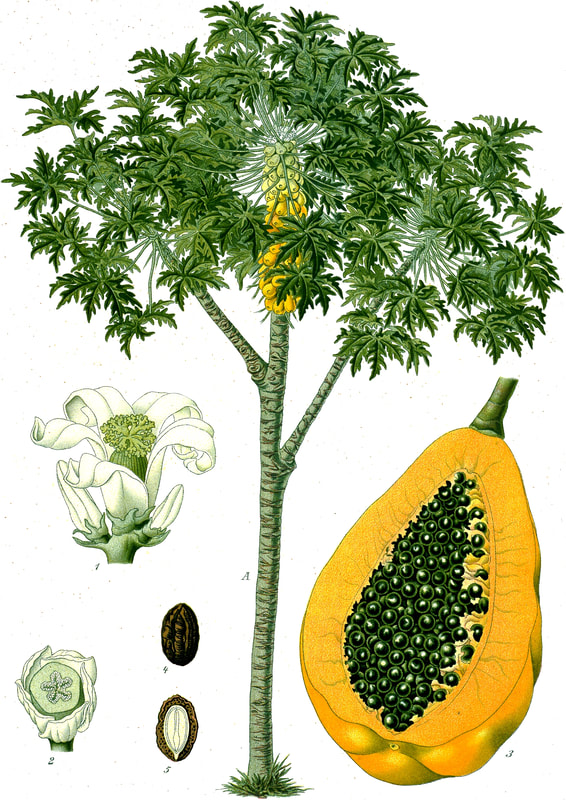

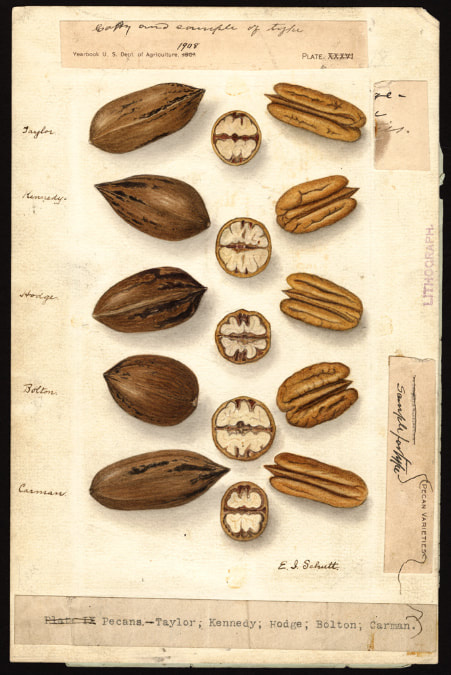

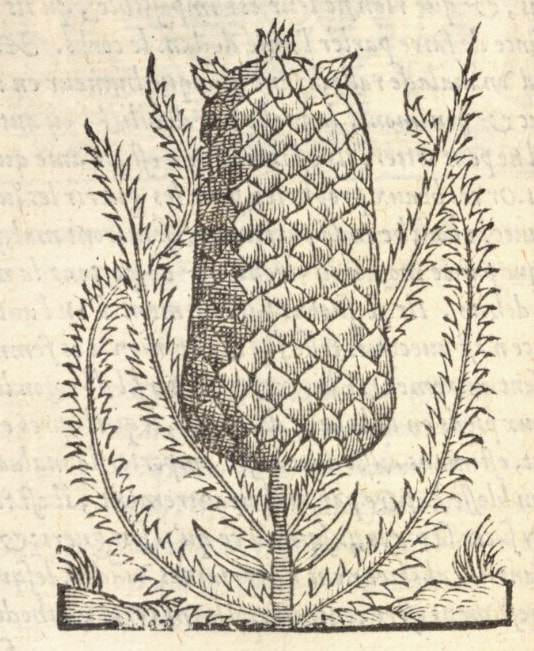

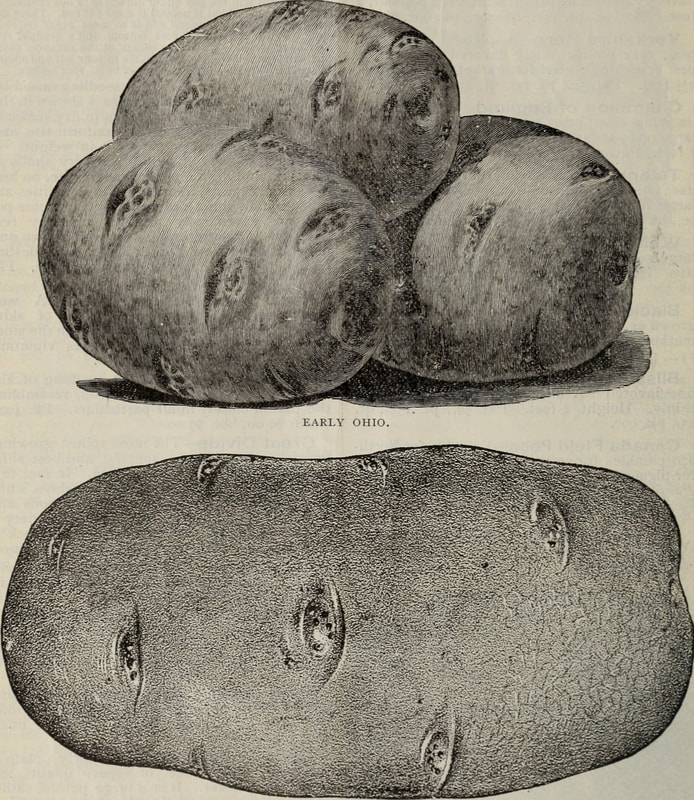

Today is Indigenous Peoples' Day. What, you thought it was Columbus Day? Well, for some people who don't know any better it still is, but Columbus was a pretty terrible person, driven by greed, and he didn't "discover" anything. Instead, he did things like sell 9 year old Taino girls into sex slavery, cut off children's hands if they didn't meet gold quotas, and generally committed genocide and slavery against every non-white person he met. He almost completely wiped out the Arawak-speaking peoples of the Caribbean, including the Lucayan people of the Bahamas and especially the Taino people of Hispaniola (present day Haiti and Dominican Republic). But as with most genocides, they're never 100% successful, and people throughout the Caribbean are descended from Taino people. One thing Columbus did lend his name to is a term called "The Columbian Exchange." The term was coined in the 1970s by historian Alfred W. Crosby, who studied the impacts of geography and biology on history, specifically the relationship between Europe and the rest of the world. Because Columbus was the first European to bring back many of the plants now used across the world, the exchange is named after him. Essentially, Irish potatoes, Italian tomato sauce, Swiss chocolate, Thai chilis, and a whole host of other important international foods are not actually from any of those places. They are ALL indigenous to North and South America and did not exist outside those continents prior to 1492. I'm going to catalog Indigenous American foodways in a minute, but first I want to emphasize how important it is to recognize that all of these foods are a result of Indigenous agricultural innovation. There is a tendency among many White folks to assume that these foods were just growing "wild" - and while that may be the case with some fruits, the vast majority were cultivated by Indigenous people, often in brilliant and surprising ways. And if you'd like to skip the list and go straight to figuring out where you can buy Indigenous foods and support Indigenous growers, harvesters, and producers, a good starting place is the list created by the Toasted Sister podcast. It's not comprehensive, but it's a great start. You can also check out this directory of certified American Indian Foods producers by the Intertribal Agricultural Council. You can even search by state! A small disclaimer - this is obviously not a complete list of Indigenous foods - I thought I would list the most influential foods globally and in the modern American diet. But I encourage you to use the magic of the internet to see what other foods you can find Indigenous to the area you live. And one final note - while it is important to preserve Indigenous foods and seeds, it's equally important to support the Indigenous people working to preserver them, like the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network. So while groups like Seed Savers Exchange are great, I encourage everyone to seek out Indigenous-owned and Indigenous-led companies and groups when choosing who to support. AmaranthWhere I grew up on the Northern Plains, in Lakota territory, one species amaranth is often known as "pigweed," and is considered a noxious weed by farmers. But Indigenous people know it as an important grain crop. Developed by the Aztec, amaranth was banned by the Spanish. The leaves of amaranth are also edible and some varieties are known as "callaloo," an important green vegetable for enslaved African peoples throughout the Caribbean and southern United States. If you're a gardener, "love-lies-bleeding" is a decorative variety of amaranth. There are dozens of varieties, but amaranth grains are often available for purchase from specialty stores and online. AvocadoAvocadoes, modern purview of hipsters, are actually an ancient fruit developed near Puebla, Mexico nearly 10,000 years ago (seriously, the world owes so much to Mexico in terms of agricultural innovation). The Indigenous residents of Puebla began cultivating the tree as much as 5,000 years ago. Modern-day avocadoes come in a whole host of varieties, but residents of the U.S. are most familiar with the Hass variety. Introduced to the American Southwest in the 1830s, avocado consumption in the United States didn't really take off nationally until the 1930s, influenced by California cuisine and used primarily in salads. Look in old cookbooks for references to "alligator pears," so named because of their bumpy green skin and pear shape. BeansBeans, especially climbing pole beans like the scarlet runner bean, are an important component of the Three Sisters style of agriculture, in which pumpkins or squash, corn, and beans are grown in concert with each other. The corn provides the stalk for beans to climb, the beans fix nitrogen in the soil for the corn and squash, and the broad leaves of the squash shade the ground, helping to prevent competing plants from growing and keeping the soil moist. Although some varieties of legumes did exist in Europe prior to the Columbian Exchange, notably chickpeas, peas, lentils, and broad beans, the introduction of the wide variety of cultivated Indigenous beans to Europe, especially kidney beans, including what would become the famous Italian cannelini. Black beans, pinto beans, and pink beans are other Indigenous varieties. Blueberries Image of the Weymouth variety of blueberries (scientific name: Vaccinium corymbosum), with this specimen originating in New Jersey, United States. Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705, 1940. Lowbush blueberries (often marketed in grocery stores as "wild" blueberries) are native to North America, as other other blueberry-like fruits including huckleberries and juneberries (also known as serviceberries). Although these plants grew wild, blueberry barrens and other stands were often maintained by Indigenous peoples. Dried blueberry and cracked corn mush may have been served at the First Thanksgiving. Early European observers misnamed them "bilberries," after a relative native to Britain. In the early 20th century, highbush blueberries were cultivated from Indigenous blueberries in New Jersey. Highbush blueberries are bigger and therefore easier to harvest and ship than lowbush blueberries and are most often what you'll find in grocery stores today. CashewMost people probably associate cashews with Southeast Asia and Indian cuisines. But cashews are actually native to Brazil. The word "cashew" is a corruption of the word "acaju," which is Tupi for "nut." The Tupi people (of which there are dozens of sub-tribes) were who the Portuguese encountered when they first arrived there in the early 1500s. It was the Portuguese who brought the cashew to Goa, India in the late 1500s, where it thrived. Today, most commercially produced cashews are grown in India. ChiaMaybe you've noticed the trend for chia puddings these days. Or perhaps you're old enough to remember the Chia Pet craze of the 1980s. But the origins of chia are much older than you might suppose. Native to Central America, chia is thought to have been cultivated by the Aztecs as much as 3,500 years ago. An important staple crop throughout Mesoamerica, it was likely also used for religious purposes and may have been banned by Spanish colonizers for that reason. Thankfully, it survived. Chilis & PeppersChili peppers - from which all modern capsicums are derived, including bell peppers - were cultivated in Mexico as early as 6,000 years ago. Self-pollinating, chilis quickly spread throughout Mexico and Central and South America. Known in many countries by their cultivar name - capsicum - in the United States we call them "peppers" because Columbus and other Europeans associated them with the heat they had previously only known from black pepper. Like cashews, chili peppers were brought to Southeast Asia by Portuguese traders, where they quickly took hold as an essential part of many Asian cuisines. In the United States, New Mexico is best known for its production of chili peppers and its chili-eating heritage. Chilis are an essential ingredient in salsa, and Indigenous Mexican peoples use all different varieties (not just jalapenos and habaneros) for different levels of heat and flavor. ChocolateToday, chocolate is most often associated with Switzerland, Germany, and France. But its origins are ancient and date to Mesoamerica. The oldest references are for the Olmec peoples of central Mexico, who used it in religious ceremonies. But it was also used by the Maya and Aztec peoples, who both used cocoa beans as currency and used chocolate beverages in daily life and religious ceremonies. Although the origin of cacao plants is contested, they appear to have been common in Central America and actively cultivated as early as 5,300 years ago. Chocolate's chemical signature is often tracked as part of archaeological digs, and recent finds have suggested that its use and cultivation are earlier and more widespread than previously known. When it was introduced to Europe, Europeans treated it much like they did another dark, bitter beverage - coffee - by adding cream and sugar to it and drinking it for breakfast. By the 18th century, mechanization and slavery had made chocolate affordable to the middle classes. But it wasn't until the 19th century that chocolate bars, mixed with vanilla, sugar, dairy solids, and cocoa butter, came into widespread use. Corn (Maize)For most Americans, corn is hybridized sweet corn, popcorn, and maybe yellow or white cornmeal (or grits). But corn comes in thousands of different varieties and can be processed in hundreds of different ways. Did you know, for instance, that different varieties of corn - popcorn, dent, flint, flour, etc. - were cultivated for different uses? And that most corn can be eaten at all stages of development? And that "sweet" corn was originally just eating immature "green" corn before the sugars had turned to starch? Indigenous cooks also developed nixtamalization - a process whereby corn is soaked in wood ashes and water (i.e. lye) to de-hull and soften the corn. Nixtamalization also has the important additional benefit of releasing the niacin (Vitamin B3) from the corn so that it can be processed by the body. Niacin deficiency, also known as pellagra, plagued 19th and early 20th century White Americans, who did not know how to process the corn properly. Corn was developed from a grass native to south central Mexico called teosinte - which is still used today in Mexico as a fodder for livestock. As cultivated varieties spread throughout North America, they took on different characteristics as they cross-pollinated with other varieties and native species of teosinte. Corn is wind pollinated, meaning that it cross-breeds easily. Today, corn's global dominance is almost entirely related to its role as livestock feed, especially with beef. Sadly, beef cattle are not well suited to being raised on corn, and "corn fed beef," which is designed to put on a lot of fat for your "well-marbled" steak, is actually extremely destructive to bovine digestive systems. Not to mention unhealthy for humans, too. American agricultural subsidies for corn, which allow food processors to purchase it for less than it costs farmers to produce, have also allowed the proliferation of its use as an industrial food, notably corn syrup, but corn is now in almost everything we eat. And not in a good way. If you want to help Indigenous producers, buy Indigenous-grown Indigenous corn products. Here in New York, you can buy Iroquois White Corn. Don't feel like eating corn but want to help? Support Indigenous seedkeeper groups. Can't find one in your area? Donate to the Indigenous Seedkeeper's Network. CranberriesToday, cranberries are most often associated with Thanksgiving and New England, but cranberries are native to the northeast of North America and were used often by Indigenous peoples in those areas. Although a variety of cranberry is native to the bogs of Britain, and the Scandinavian lingonberries are a relative, the vast majority of modern cranberry consumption is based on species native to the U.S. and Canada. Maple Syrup & SugarMaple Syrup is one of the few sweeteners native to North America (honeybees, sugar cane, sorghum, and sugar beets are all imported). First used by Indigenous peoples in the Northeast, it is unclear which tribes first started use of maple sap as a sweetener. One Haudenosaunee/Iroquois legend indicates that the people first observed red squirrels cutting into the bark of maple trees and returning to drink the sap that flowed out. This has since been confirmed by scientific observation of squirrel behavior. Maple syrup and sugar was made either by freezing the water out of the sap, or by boiling with heated rocks. European colonists were quick to adopt maple sugaring as an important source of late winter calories and shelf-stable year-round sweetener. Although for some reason in the United States maple products are associated with fall, maple sugaring time is usually in March, when daytime temperatures rise above freezing, and fall below freezing at night - perfect conditions for optimum sap production. PapayaThe native range of the papaya is from southern Mexico to northern South America, although it has been naturalized throughout the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. With a quick maturity - some papaya can produce fruit after just one year - Europeans spread the plant to other tropical regions around the world where it is widely used in many different stages of ripeness, both cooked and raw. PeanutsThe archaeological record of peanut cultivation is not clear, but it is clear that it was present in Brazil and Central America in the 16th century when European explorers arrived in South America. The peanut is not actually a nut - it is a legume and more closely related to beans than, say, pecans. But its culinary importance grew once it was imported by Europeans to Africa and Asia. The peanut actually came to North America by way of enslaved Africans, who carried it with them as they were stolen from their homelands. The peanut was largely regarded as animal fodder by Europeans, and used in subsistence farming by enslaved Africans and African-Americans in the U.S. In the late 19th century, a number of people, including John Harvey Kellogg and Heinz, were filing patents for peanut-butter-like substances. Ironically, George Washington Carver, African-American plant scientist and the man most associated with peanut butter, didn't actually invent it. Today, about the only people who don't enjoy peanuts much are Europeans, which is ironic given their role in spreading them globally. PecanNative to North America, the pecan is one of my favorite nuts. Its native range ran from New England to Mexico and was widely used by Indigenous peoples. The word "pecan" likely comes from a 16th century European corruption of the Algonquian word "pacane," describing nuts that required stones to crack. Hickory nuts (also known as butternuts) and black walnuts are in the same family as pecans. PineappleAlthough most Americans associate pineapples with Hawaii, they are actually native to the Paraguay River basin, which stretches between modern-day Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina. Pineapples were cultivated by the Maya and Aztecs and Europeans first encountered them in the 15th century. Named the "pine apple" because of its resemblance to a pine cone and its status as a fruit, Europeans were able to grow some pineapples in greenhouses. In the 18th century, the pineapple was a symbol of hospitality and wealth and were much smaller than modern-day cultivars. Pineapple plantations were first installed by White Americans in Hawaii in the 1880s. James Dole made his fortune with pineapple plantations, processing, and canning innovations, which introduced the pineapple to ordinary Americans across the country. PotatoesWhat would Europe be without the potato? And yet, this starchy tuber, which spread throughout the Andes mountains prior to European contact, is originally from the border of modern-day Peru and Bolivia and dates back as far as 8,000 years ago. Cultivated from the wild tuber by Indigenous agriculturalists, over 5,000 varieties now exist. Potatoes were the staple crop of the Inca, who built their empire on it. Andean Indigenous peoples used it in all the usual ways, but also pioneered a special preservation technique called chuño, whereby the potatoes were frozen and dried in a way that made them very light and allowed them to keep for years. Chuño was usually prepared as part of a stew and was an important cash crop for Indigenous farmers. Prior to its introduction to Europe, most of the poorer classes relied on turnips and rutabaga for starchy bulk calories. But the potato was not only more palatable, it was more prolific, easier to grow, and it kept longer in storage. The shift to potatoes throughout Northern Europe in particular meant that the advent of potato blight in the mid-19th century, particularly in subjugated Ireland, started a mass migration of Europe's poor to the nations which had fed them so well for so long. QuinoaAlso native to the Andes and Peru, quinoa (pronounced "keen-wah"), is a member of the amaranth family. Used as a cereal crop by the Inca and other Indigenous peoples in the Andes mountains, quinoa has been in cultivation for as many as 5,000 years. When the Spanish arrived, determined to stamp out Incan culture, quinoa almost disappeared, but it persisted. Its "discovery" by White Americans interested in "superfoods," the price of this essential Indigenous grain actually skyrocketed. Whether or not this is good for Indigenous farmers is a matter of some debate, but when in doubt, be sure to buy from Indigenous producers. Squash & PumpkinAlong with corn and beans, squash make up the famous "Three Sisters" of Indigenous foodways. One of the oldest cultivated crops of the Americas, dating back as many as 10,000 years ago (before maize and beans), squashes are native to the Andes and Mesoamerica and wild varieties actually predate human inhabitation on the continents. Their cultivation was widespread throughout North and South America prior to European contact. All global varieties of squash, including pumpkins, zucchini, and decorative gourds, originated in the Americas. The word "squash" is an English corruption of the Narragansett word "askutasquash" meaning "a green thing eaten raw." Today, pumpkins (a word for a particular kind of large, round, orange squash that doesn't actually have an official classification) are mostly associated with Thanksgiving and New England foodways, although in the 19th century they were also stereotypically associated with slavery. They were one of the Indigenous foods featured in the first "American" cookbook, published by Amelia Simmons in 1796. SunflowerSunflowers are also native to North America, thought to have been cultivated near present-day Arizona and New Mexico around 3000 BC. Cultivated for their oily seeds and tuberous roots (also known as sunchokes or "Jerusalem artichokes"), sunflowers were also sometimes used as dyes. Although they were an important crop for Indigenous peoples, they were not in widespread use by European-Americans until their popularization in 19th century Russia, where they had been imported. Today, North and South Dakota are the biggest producers of sunflowers in the US and sunflower seeds, "sunbutter" and sunflower oil are popular modern uses. Not so much with the "sunchoke," although the tubers are regaining some popularity. Sweet PotatoSweet potatoes are native to Central America. Although called "potatoes" and sometimes "yams," they are not related to either plant. Sweet potatoes are more closely related to morning glory and bindweed. Sweet potatoes were spread across the Pacific nearly 400 years before Columbus by Polynesians, who brought the vine back with them. It was the Spanish and the Portuguese, however, who spread the sweet potato to the Philippines and Japan, respectively. The Spanish also brought the sweet potato to West Africa, where it was adopted, but not without some derision as its taste. The yam is native to Africa, which is likely why so many Americans, especially African-Americans, call sweet potatoes "yams." TomatoWhich is more authentic? Italian tomato sauce, or Mexican salsa? Hate to break it to you, but the Mexicans have the ayes on this one. Wild tomatoes are native to Western Mexico and were originally tiny, sour, and hard. Careful cultivation by Indigenous people led to thousands of more edible varieties, including husk tomatoes ranging from tomatillos to ground cherries. In Nahuatl (the Aztec language), "tomatl" was used to reference green tomatoes like tomatillos, and "xitomatl" was used for red varieties. The Spanish translated it as "tomate" and hence the term "tomato." When brought back to Europe, the bright red fruits were originally identified as a type of eggplant (both are members of the nightshade family), it garnered the nickname "love apple," and was originally considered poisonous. Although it was cultivated as a decorative plant, it was not in widespread use in Europe until the mid-18th century. It's widespread adoption in Italy was likely connected to nationalist sentiments in the 19th century and its association with the color red in the flag of Italian unification. In the United States, Thomas Jefferson may have helped popularize the tomato outside of the American southwest. And his relative by marriage, Mary Randolph, featured tomatoes in her Virginia Housewife cookbook, published in 1824. By the end of the 19th century, tomatoes became a popular American preserve, providing color, acidity, and sweetness to the typical American table. TurkeyIndigenous to North America, turkeys have been consumed by Indigenous peoples for centuries. Turkeys were domesticated in Mesoamerica as early as 800 BC. The Spanish brought back domesticated Aztec turkeys to Europe, where they quickly joined the European game bird lexicon. Associated with Christmas in Britain as early as the 17th century, the British Christmas goose persisted until the 20th century. In the United States, turkey is most commonly associated with Thanksgiving, although it is also often consumed at Christmas. Turkeys are one of the only indigenous American meat animals widely adopted in Europe and elsewhere. The name "Turkey" is likely associated with how Europeans were first introduced to turkeys - either through trade with the Middle East, or in association with guinea fowl as a game bird, introduced via Turkey. Domesticated turkeys are thought to have been descendants of Aztec domesticated birds reintroduced to North America via Europe. The turkeys purportedly eaten at the First Thanksgiving would have almost certainly been wild varieties, however. A shift to large scale commercial poultry production in the early 20th century has helped introduce turkey into the American diet through things like sliced deli turkey. The virtual disappearance of wild turkeys from New England due to deforestation meant that they had to be reintroduced to New England, an effort that began in the 1960s. VanillaVanilla is an orchid native to the Caribbean and south Central America. Cultivated by pre-Columbian Maya people, it was widely adopted by subsequent Indigenous peoples, including the Aztecs, who added it as a flavoring agent to their chocolate beverages. Attempts to cultivate vanilla in Europe were unsuccessful, largely because vanilla is naturally pollinated only by a native species of bee. An boy named Edmond Albius, enslaved on the Island of Reunion, pioneered a hand pollination technique that allowed vanilla to spread across the globe, including to the islands of Tahiti and Madagascar. Wild RiceWild rice, known in Anishinaabe/Ojibwe as "manoomin," is, indeed, a wild rice. Growing in marshy lakes, truely wild rice is harvested by hand from the wild. Wild rice is central to Anishinaabe culture, and one legend indicates that Ojibwe people emigrated from the Atlantic coast to the "place where food grows on the water." Although Northern wild rice is the most common, other two other varieties are native to North America - one in Florida and one in Texas. Suggestions to grow wild rice commercially were suggested as early as the mid-19th century, but it was not attempted on any scale until the 1950s. Commercially cultivated "wild" rice is now a great source of controversy, as is the genetic modification of wild rice. Opponents argue that commercial wild rice conflicts with Indigenous food sovereignty and treaty rights. True wild rice can also be endangered by relaxed water pollution standards, oil pipelines, and more. Indigenous people were rarely if ever involved in the research and are not beneficiaries of commercial varieties. For reasons of taste and to support Indigenous tribes and businesses, I strongly recommend that you source your wild rice from Indigenous producers. ConclusionPhew! That is a LOT of influential foods developed by Indigenous Americans. I hope you learned something with this catalog - I know I did. And I hope you'll support Indigenous food producers by purchasing direct whenever you can. Thanks to the magic of the internet, that's now possible more than ever. And for those of you interested, I'm planning a couple more posts (and a few talks) about the influence of pumpkins, corn, wild rice, and more. So stay tuned! What's your favorite Indigenous American food? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! If you found this article interesting, useful, and/or thought-provoking, join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

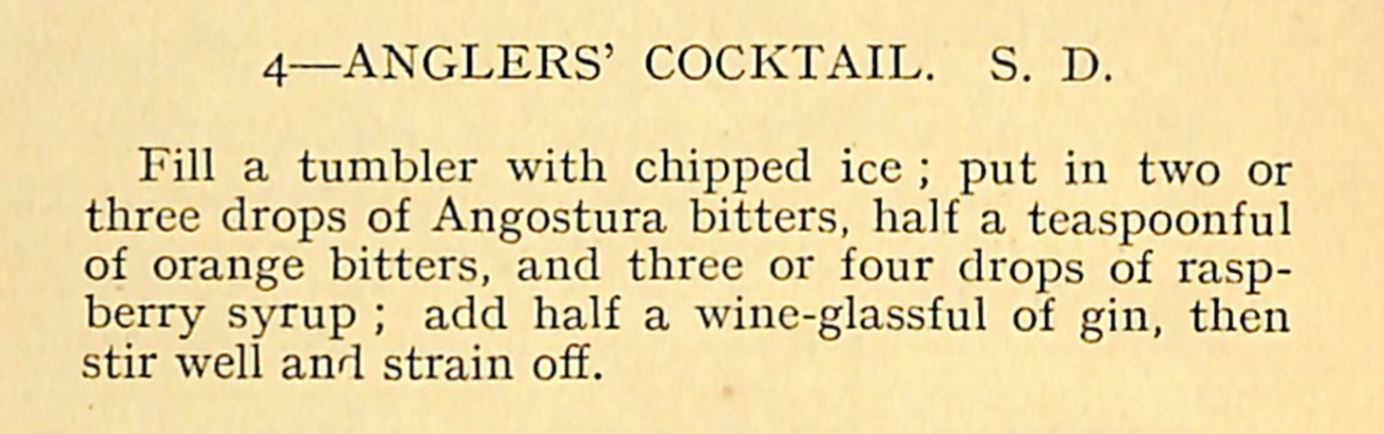

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Angler's Cocktail from Recipes of American and Other Iced Drinks, London (1909).

Because it's Labor Day Weekend and traditionally one of the biggest travel dates of the year, I thought we could talk about road food! We discussed the development of early federal highways, including Route 66, the Eisenhower Interstate Highway System, the Green Book and Driving While Black, rest areas versus service areas, Howard Johnson's and the development of other fast food chains, Gourmet and Ford Motor Company travel books on regional restaurants, the work of Jane and Michael Stern to catalog regional foodways, and the foods people took with them while traveling, roadside stands, and more. Angler Cocktail (1909)

Here's the original recipe, from Recipes for American and Other Iced Drinks by Charlie Paul (1909):

Fill a tumbler with chipped ice; put in two or three drops of Angostura bitters, half a teaspoon of orange bitters, and three or four drops of raspberry syrup; add half a wine-glassful of gin, then stir well and strain off. Here's my version: 3 drops Angostura bitters 6 drops orange bitters a dash of raspberry syrup 2 ounces American gin Add to a cocktail shaker of crushed ice - swirl until cold, then strain into a cocktail glass. It's quite lovely - very floral and a pretty shade of peachy gold. I would add more raspberry syrup next time as I couldn't taste it at all and the drink was not sweet at all. Episode Links:

We're switching to a twice-a-month schedule, so join us on Friday, September 18, 2020 at 8:00 PM EST for the next episode of Food History Happy Hour!

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

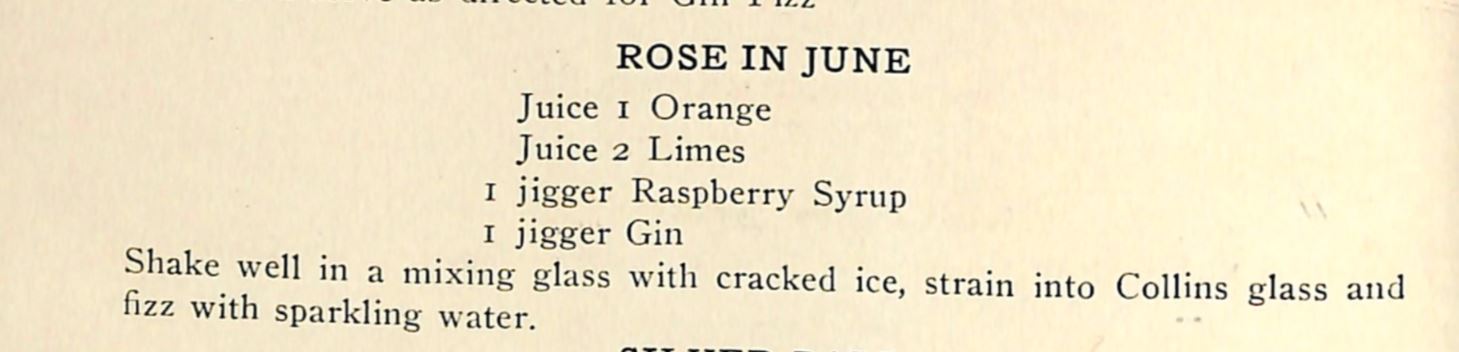

It's Juneteenth! Thanks to everyone who joined us for Food History Happy Hour. This week we make the Rose in June cocktail from the 1917 "Recipes for Mixed Drinks." We discussed Juneteenth, red velvet cake, victory gardens including propaganda and the exclusion of Black farmers and imprisoned Japanese Americans, the role of visuals in influencing taste, Black Food Historians You Should Know, disparities in book contracts, hot weather foods, salads, summer kitchens, how historical peoples coped without air conditioning, how historical peoples kept foods cold before refrigeration, ice and ice cream in the ancient world, rural electrification and electric refrigerators, the Frigidaire Cookbook, icebox pie, racial stereotypes in food advertising, including the history of the "Aunt" and "Uncle" terms, including Uncle Ben and Aunt Jemima, the history of the mammy trope, the tragedy of child caring roles, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Black children in advertising, Franchise: the Golden Arches in Black America, the forthcoming book scanner I ordered, monuments and statues, and we ended with a signal boost for the James Hemings Society.

Rose in June Fizz (1917)

The "Rose in June" cocktail comes from the "Fizz" section of Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo Ensslin (1917).

The original recipe calls for: Juice of 1 orange Juice of 2 limes 1 jigger raspberry syrup 1 jigger gin Shake well in a mixing glass (or cocktail shaker) with cracked ice, strain into Collins glass and fizz with sparkling water OR - if you don't have fresh citrus fruits OR raspberry syrup - you can substitute 1/3 cup orange juice, 1/4 cup lime juice, a heaping tablespoon of raspberry (or in my case, strawberry) jam, and the gin. Very nice, very refreshing, but sadly NOT pink.

Here's a roundup of links related to everything we talked about (in addition to all the links above!):

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

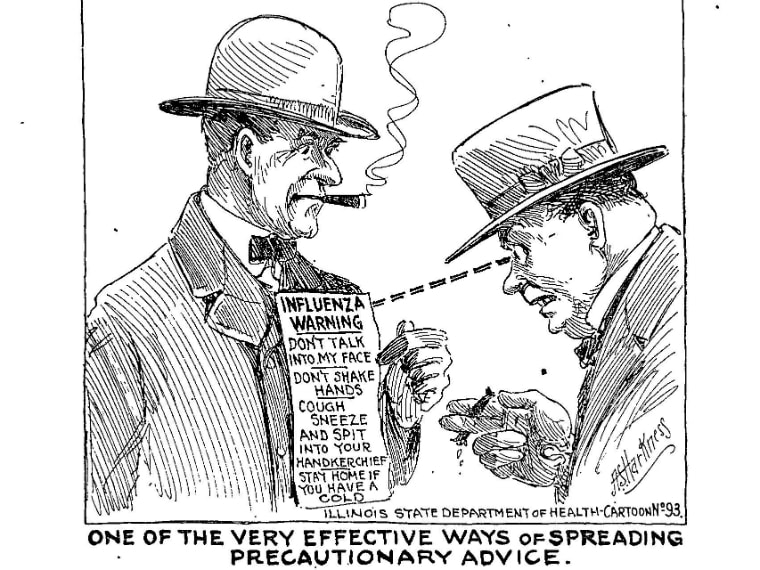

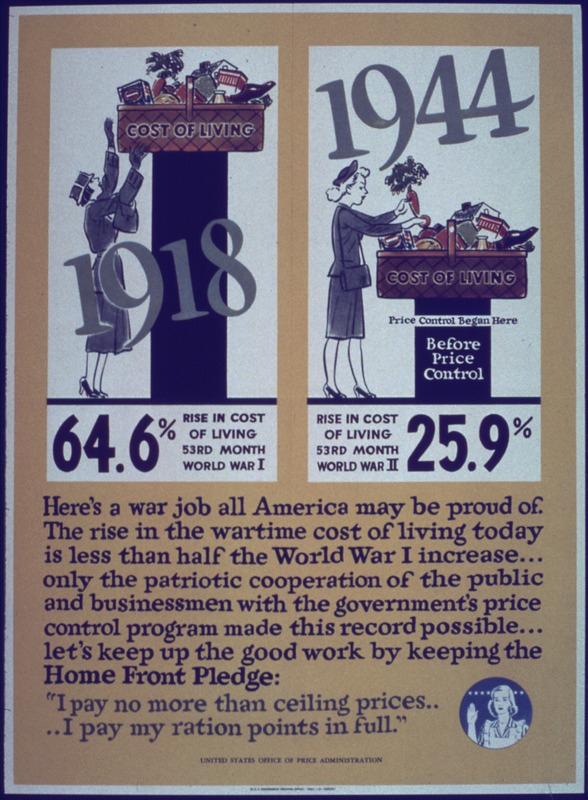

Y'know that old saw, "Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it?" Well, like a lot of old adages, this one has a big grain of truth in it. Historians often can see parallels to the modern world as they study history. Indeed, my area of specialty - the Progressive Era and World War I home front - has led to LOTS of comparisons to modern life. But with the addition of the coronavirus lockdown, the comparisons grew more numerous. To that end, I thought I would catalog some of the striking similarities. Failure of Bureaucracy: Military SupplyOne thing that has becomes especially striking at this time is the failure of the federal government to manage national supplies during an emergency. In this instance, it's the management of medical supplies for COVID-19, particularly personal protective equipment (a.k.a. PPE). States are competing on an open market and with each other, driving up prices and leading to shortages. To make up the shortfall, ordinary citizens are creating homemade versions of masks, face shields, and other equipment. During the first months of the U.S. entrance into World War I, the exact same thing was happening. Historian Robert Ziegler in his book America's Great War: World War I and the American Experience, outlines the deplorable state of military supply following the Spanish American War. Individual battalions were competing with each other on the open market to purchase supplies, thus driving prices up. In addition, the United States had never fielded such an enormous army and the production of other military supplies, such as uniforms and rifles had yet to keep up with the demand of a suddenly-enormous army. According to historian David M. Kennedy, in his book Over Here: The First World War and American Society, soldiers were sent to Europe with hardly any training. Men and boys who had been recruited in July, 1918 were on the front lines by September. Some men arrived never having used a rifle, and had to take an intensive 10 day course before being sent into battle. The logistics of shipping war materiel, both within the borders of the United States and overseas was also a mess, causing railroad and port backups. Some credit the poor supply of soldiers in training camps (inadequate clothing, bedding, housing) with exacerbating the effects of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Combined with this was the efforts of the American Red Cross. Famed for providing bandages and nursing aid during the American Civil War, thousands of chapters sprang up across the nation and throughout 1917, women were encouraged to "knit their bit" by knitting sweaters, socks, wristers, and watch caps for "our boys" being sent overseas. Why? Likely because military supply chains were, as stated, in shambles and because it was easier (and cheaper) to task the nation's women with keeping soldiers warm than to mobilize factories. Wool socks in particular were in high demand because of the poor conditions in the trenches. But by 1918, according to historian Christopher Cappazola in his book, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, the federal government was frantically telling women to STOP knitting, likely because military supply was completely reorganized. Although there are plenty of resources about knitting in WWI and the American Red Cross (including this lovely one), few people seem to have made the connection between "knitting your bit" and the failure of military supply. It was only part-way through American participation in the war that the federal government reorganized military supply under a centralized Quartermaster General. It wasn't until the Korean War that the United States passed the Defense Production Act (1950), which empowered the federal government to compel private business to prioritize the production of war materiel and prevent hoarding and price gouging. If the United States were to learn the lesson of WWI supply today - the federal government would coordinate with individual states to purchase - and allocate - medical supplies where most needed, instead of bidding against states on the open market. Xenophobia, Immigration, RaceIn the years leading up to the First World War, the United States was inundated with immigrants from all over the world, but particularly Eastern and Southern Europe. The United States was also recovering from the abandonment of Reconstruction and Black Americans were becoming more and more prosperous, with a growing middle class. Combined with a brain and labor drain on rural areas, this led to people like President Theodore Roosevelt warning of "race suicide" for White Anglo Americans unable to keep pace with the more fertile immigrants. Roosevelt also worried about rural life and started the Country Life Commission to study and combat the drain of population from rural America to urban areas. Tempted by "cosmopolitan" life, reformers worried, young people would be corrupted and the bedrock foundation of democracy - the landowning yeoman farmer - would diminish. Unfortunately for reformers, the majority of people in rural areas lived difficult lives and particularly in the South, most did not own the land they farmed. But the idea that rural America, and farmers in particular, are the "salt of the earth" is an idea that has persisted even today. With "flyover country" being courted by politicians, especially conservative ones, with every election. Immigration and race remain hallmark dogwhistles in modern politics. The Trump campaign used the slogan "America First" on the campaign trail - echoing the campaign slogan of Woodrow Wilson leading up to his first term as a neutral isolationist. It was a policy he would abandon in his second term, as the U.S. entered World War I in the spring of 1917. Americans were notoriously isolationist in the early 20th century (except for their colonialist ambitions in Central America, Hawaii, and the Phillipines) and America's first propaganda machine had to be created to convince them that joining the war was a good idea. To convince them, Woodrow Wilson invented the idea of defending and spreading democracy (and American exceptionalism) abroad - a policy that has continued to be used in every American war since then. Attempts to Americanize immigrants remained in effect throughout the war. Progressive reformers from settlement houses and canning kitchens on up to proponents for the war which thought a draft would help Americanize immigrants tried to force people into the mold of White Anglo American (usually Northeastern) culture. Black Americans faced similar pressures, and segregated versions of just about every middle-class voluntary organization - including the Red Cross - was implemented during the war. Following the war, newly economically mobile Black Americans, buoyed by industrial jobs for war production, faced even more hostility than before. Resentment by racists clashed with confident (and armed) veterans returning from war. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is just one example of Black WWI veterans attempting to defend themselves and their communities. Race riots, lynchings, and a dramatic expansion of the Ku Klux Klan were the hallmarks of 1919, 1920, and beyond. Today, Black American communities still deal with over-policing, incarceration, and violence. Latinx-Americans have dealt with a dramatic ramp-up of incarceration, family separation, and deportation (even of children), as well as more casual racism. And Asian-Americans in particular have borne the brunt of some horrific incidents of racism directly related to the coronavirus - as the ignorant believe that they (regardless of whether or not they had been to China recently, or were even of Chinese descent) were "carriers" of the disease - another old saw of racism most famously used by Nazis against the Jews (among others). The High Cost of LivingIn the two decades leading up to WWI, the United States underwent a series of depressions and recessions. Starting with the Depression of 1893 (which the US did not recover from until 1897-98), and with smaller recessions in 1907 and 1913-14, the "high cost of living" (commonly abbreviated as "HCL" or "H.C.L.") saw a dramatic rise in cost of living, including food and housing, while wages stagnated. Called "stagflation" by economists, this situation led to labor unrest, and strikes, food boycotts, and food riots were all common during this time period. Socialists were also in political ascendancy due to income and labor inequalities. Labor strikes were often broken by deadly force. Food boycotts and riots remained the purview of the desperate - often women with starving children which tugged at the heartstrings of wealthy and middle-class White Progressives, even as some were organized by socialist activists (read about the 1917 food riots in New York City). Many of the strikes and riots of the 1900s and 1910s led to serious labor reform, including the ending of child labor, worker safety reforms, reduced hours, and more. New York City during WWI tried to pass a minimum wage law, but it was vetoed by the Mayor. Today's parallels include a different sort of high cost of living - most "luxury" items are cheaper than they've ever been, but housing, education, healthcare, and food costs have risen by as much as 200% in the last 20 years. In addition, democratic socialists and real, "bread and roses" socialists have seen their numbers spike in the last few years. Activists are fighting for a minimum wage increase, universal healthcare, and other reforms, although union membership has taken a steep dive in the last few decades. Coronavirus has only highlighted the "essential" role many low-wage workers play in American life, and some retail workers, cleaners/janitors, and restaurant workers are now being hailed as heroes alongside medical professionals and scientists. War Gardens & RationingOne particularly fascinating trend that appears to be occurring right now is the skyrocketing sale of vegetable seeds and plants. Tied in part to the fact that so many Americans are sheltering in place and have time to garden, the resurgent interest in "Victory Gardens" is also a reaction to temporary shortages in grocery stores (due to logistics, rather than supply) and fears that the food supply might be endangered by coronavirus. The First World War was also one of the first times in American history that a concerted effort to get ordinary people to plant kitchen gardens. Of course, part of that was because of the changing demographics of population. People in rural areas had almost always had kitchen gardens. But as more and more people moved into urban and suburban environments, and fresh food supplies became easier and cheaper to acquire, kitchen gardens became less necessary, and most people who could afford to focused on flower gardens instead. But the U.S. entrance into the war, with its commitment to feeding the Allies, came with very real fears that food would be in short supply. This was reinforced by rhetoric from Wilson and Herbert Hoover, the new U.S. Food Administrator, who knew that in the spring of 1917, existing crops would be inadequate to feed both Americans, their growing army, and the Allies without serious changes. Enter war gardens and voluntary rationing. Hoover was the brains behind the idea of voluntary rationing - he wanted Americans to show the world their personal fortitude and strength through voluntary efforts, including rationing. He also believed that the bureaucracy necessary to enforce mandatory rationing would not only be hugely expensive, it would also be ineffective. To lead by example, Hoover and the entire Food Administration were all volunteers. Rationing included refraining from eating wheat, meat, butter, and sugar whenever possible, and by the fall of 1917, "wheatless, meatless, and sweetless" days were implemented. Grain and flour substitutions, sugar substitutions, and vegetarian meals became more normalized during the war. The National War Garden Commission was also a voluntary organization, albeit a private, not public, one. Started by forestry magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, it encouraged Americans, especially school children, to plant "war gardens" (later renamed "victory gardens," a name that would resurface during WWII) which would provide fresh vegetables for ordinary people. Not only would this free up conventional food supplies, the production of local food would also free up transportation resources, which by the end of 1917 were becoming so congested that the United States temporarily nationalized its railroads. Spanish Influenza "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. And, of course, the obvious one. I've already written a bit about the Spanish Flu, but it bears noting that during the course of the 1918 pandemic, the government was reluctant to report real numbers or spread information about the severity of the pandemic because they were worried that it would endanger the war effort or reduce morale. Some cities, like Philadelphia, held enormous and patriotic Liberty Loan parades, allowing the virus to spread like wildfire. In fact, despite evidence that the influenza strain likely started in the United States, it wasn't until neutral Spain was infected, and its newspapers reported the real death toll, that the general public learned of the pandemic. Hence the name, "Spanish Influenza." Similar things are happening now, with the Trump Administration's initial reluctance to admit coronavirus was a serious problem because they feared the effect on the economy. Conflicting information in the media (and from the President) about the severity of the virus and the need for social distancing and stay at home orders have exacerbated the problem here in the U.S. More recently, a dearth of testing has led to some experts to conclude that the death toll is severely underreported. We are now also learning that China has likely suppressed or underreported the true infection rate and death toll from coronavirus. Thankfully, unlike 1918, when newspapers largely cooperated with government propaganda efforts (under threat of having their licenses revoked, effectively putting them out of business), modern information is more accessible and immediate than ever through the internet. Although sifting fact from fiction is a bit more difficult these days. ConclusionThere are a number of other Progressive Era similarities to modern life - women's rights, environmental conservation, voting rights, and income inequality, to name a few - that I chose not to include in this list largely because they were less immediately relevant to the coronavirus pandemic. To learn more about food in World War I, check out my Bibliography page, which was links to lots of great books. I hope you enjoyed this read. It certainly helped me organize my thoughts around these similarities and I hope that we can learn from the successes and failures of the past. That's all any historian can hope. Thanks for reading. Stay safe, stay home. If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

It's Black History Month here in the United States, and while I firmly believe that Black history should be studied and celebrated year-round, I thought this would be a good time to highlight some of the good articles and important contributions by Black food historians and cookbook authors.

I'll be sharing articles on Facebook all month, but wanted to make some lists for reference, plus links to lots of great books! The following historians are in no particular order, but you should read about them all! And if you want to support them (and, by extension, The Food Historian), you can purchase one or more of their books! Jessica B. Harris

Dr. Jessica B. Harris is considered one of the foremost experts on African diaspora food and has written a number of books and cookbooks on the subject. In 2019, she was inducted into the James Beard Foundation Cookbook Hall of Fame. She was also featured on "The Food that Built America," along with numerous other television appearances.

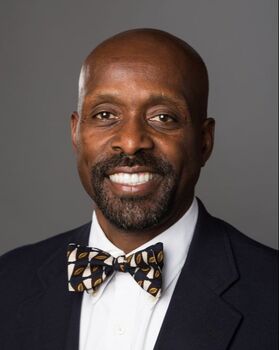

She is probably best known for her 2012 history, "High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America," which links Southern (read: African) food traditions back to Africa and their connections to slavery. You can learn more about Dr. Harris on her website, or check out one of her numerous books! Adrian Miller

Adrian Miller is the Soul Food Scholar. He is a certified barbecue judge and culinary historian whose two books, "Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time," and "The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas," have both won numerous awards. He's currently working on a new book, "Black Smoke," a history of African American barbecue culture.

Tonya Hopkins

I first met Tonya as she was recreating a 19th century African-influenced dinner that Black cook Anne Northup (wife of Solomon Northup - of 12 Years a Slave fame) might have cooked while she was working at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City. I had a wonderful time and Tonya lives up to her "griot" name as a fantastic storyteller. Although Tonya has not yet written her own book, she has contributed to numerous scholarly publications. She is also co-founder of the James Hemings Foundation, named after Thomas Jefferson's enslaved, French-trained chef de cuisine, and consultant on the upcoming exhibit at MOFAD, "African/American: Making the Nation's Table."

Michael Twitty

Michael Twitty is a bit unique in this group - not only is he a researcher, cook, and writer, he is also a historical interpreter. Twitty first rose to prominence with his 2013 Open Letter to Paula Deen, calling out her racism and appropriation of African American foodways under the guise of "Southern" food. In 2017, he published "The Cooking Gene," which Twitty calls, "a genealogical detective story, a culinary treasure map, a blueprint for finding your roots, a series of history lessons, a revealing memoir and a spiritual confessional sprinkled with recipes." In 2018, it won the James Beard Foundation's Book of the Year Award. You can read more of his work on his blog, Afroculinaria.

Toni Tipton-Martin

I first heard of Toni Tipton-Martin with the buzz around the publication of "Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks," which was the 2016 James Beard Foundation Book Award winner. I purchased a copy at an OAH conference and loved it. Toni also had a longstanding career as a food journalist and is a cookbook writer as well. You can learn more about her on her website.

Frederick Douglass Opie

Fred Opie (PhD) is a Professor of History and Foodways at Babson College. He has written a number of engaging food histories, including one of Zora Neale Hurston's WPA-era writing on Florida Food. Fred also hosts a podcast and writes extensively about foodways on his blog, in addition to other projects.

Psyche Williams-Forson

Psyche Williams-Forson is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of American Studies at University of Maryland College Park. Psyche is probably best known for her work, "Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power." She has also curated two online exhibits: "Fire and Freedom: Food and Enslavement in Early America,” for the National Library of Medicine and “Still Cookin’ by the Fireside,” an online text and photo exhibition on the history of African American cookery for the Smithsonian Institution’s Anacostia Museum.

Marcia Chatelain

Marcia Chatelain is a Provost’s Distinguished Associate Professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University. She was a Eric & Wendy Schmidt Fellow at New America from 2016-2018. She spent her fellowship year on a book that explores visions of economic and racial justice after 1968 and the fast food industry. That book is "Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America," about building Black wealth and the role of fast food franchising in post-Civil Rights America, and it was JUST published in January, 2020!

Leni Sorensen

Leni Sorensen is a culinary historian and historical interpreter extraordinaire. Consulting with places like Colonial Williamsburg and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, she is an expert on African-American foodways and Virginia cookery, particularly the work of Mary Randolph, who published The Virginia Housewife in 1824. Leni is now retired from museum interpretation, but continues to work as an independent scholar. You can learn more about her via her website. Or, read this great 2010 interview with Virginia Living.

I'm sure I've forgotten a few! If I have, please contact me and I'll update the list. If you enjoyed this list and you want to support The Food Historian (and all these wonderful historians!) you can just click on the cookbook images and purchase their books from Amazon! The authors will get their royalties and The Food Historian will get a small commission.

Or, if you're so inclined, you can join us as a member of The Food Historian. You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

"Henry Browne, Farmer" - film produced in 1942 by the United States Department of Agriculture, digitized by the Prelinger Archive of archive.org.

Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1943, "Henry Browne, Farmer" was a propaganda film produced by the United States Department of Agriculture in 1942. It is also one of the few major propaganda pieces (there were many thousand smaller efforts) directed specifically at African Americans.

In it are many hallmarks of post-Reconstruction life for African Americans in a white supremacist country. References to using only mules instead of a tractor. Eating cornbread and fatback last year, but having a cow and chickens, meaning milk and eggs for breakfast this year. Specific programs are not mentioned, but it is clear that by cooperating with the federal government to grow peanuts, that the Browne family is also participating in other endeavors, like raising chickens and keeping a victory garden. Children, in particular, were encouraged in rural areas to raise chickens (like "sister" in the film), dairy cows ("brother's job), and help with Victory gardening and around the farm. Similar programs around pig clubs and tomato canning clubs were in use during World War I as well. The film, which sadly does not record any of their voices (just the voiceover), ends with the family going to visit their oldest son, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen. This is both a call to service for all Americans and "proof" that the family is just as patriotic as any white American. This film was groundbreaking in that it put African American farmers on equal footing with other Americans joining the war effort. It emphasized Henry Browne's good agricultural techniques, like saving burlap bags instead of throwing them away, and greasing and covering farm equipment, which meant that it was likely to "last the duration" in a time when steel was in short supply and new farm equipment was likely to be expensive or impossible to get. It also did not have too many hallmarks of racism, which is surprising for the time. Unlike during the First World War, the United States propaganda machine during WWII was broadening the definition of who "counted" as an American, to give a little more credence to the idea that Americans were fighting to preserve democracy and freedom abroad. Unfortunately, the message was ultimately still hypocritical as many Black people in the south were being terrorized by Jim Crow laws, police, incarceration, and the Ku Klux Klan. However, a Civil Rights movement, which had been borne out of the returning Black soldiers of World War I and which broadened during World War II, was underway, as African Americans sought to free themselves from terror, discrimination, and disenfranchisement. World War II would mark the end of an era for many Black farmers in the rural south. Industrial work in northern and coastal cities, long a draw for those escaping sharecropping and other slave-like conditions in the South, became a bigger draw during the total war mobilization of the nation's industries. Thanks to protests from African American unions like the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the NAACP, Franklin D. Roosevelt was forced to create the Fair Employment Practices Committee in 1941, which banned discriminatory hiring in federal agencies and for companies employed in defense work, which for the first time allowed many African Americans to receive fair wages and work conditions for the first time. In addition to this draw off of the farms, there is evidence that the USDA engaged in discriminatory practices which helped drive African American farmers off of their land and caused nearly 90% of black farmers to lose their land in the years following World War II. Pete Daniel's book Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights explores this topic in more detail, and in fact, until very recently, the USDA continued their discriminatory practices. In all, "Henry Browne, Farmer" is one of the better propaganda films to come out of the Second World War. With quiet assurance and emphasis on the important work of ordinary Americans to do their part, it lacks the overly patronizing tone and bombast of other "documentaries" from the period. It's one of my favorites, and I hope you enjoy it as well. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed