|

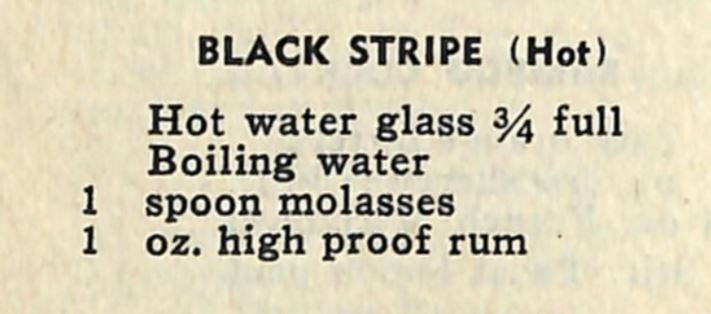

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week we made the Black Stripe cocktail - really a hot toddy - from the Roving Bartender (1946). We discussed unusual historic and heirloom vegetables, terrapin and mock turtle soup, the Victorian obsession with game meats, veal, the origins of Caesar salad, springtime greens and foraging, vegetable species diversity and gardening, heirloom grains, the centralization of American food production, tanneries and slaughterhouses, Laura Ingalls Wilder, and updates on my book! Black Stripe Cocktail (1946)I have to admit, this was not my favorite cocktail, but I think it might be that I am simply not a fan of hot toddies. As friend and bartender Mardy and I agreed, "That's a toddy! Hot watery alcohol." Lol. Fill a hot water glass (or an Uffda mug) 3/4 full with boiling water Add 1 spoon of molasses 1 ounce high proof rum (OR 1 1/2 ounces apple pie moonshine) Stir and drink while hot. If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

0 Comments

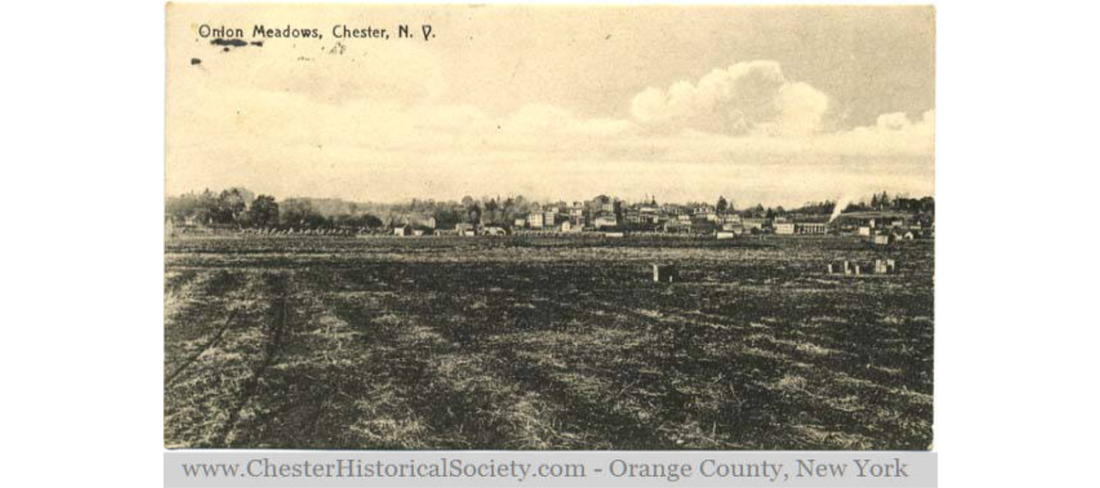

Okay folks. Here's where the history gets real. I've felt often in the last several years that the events of the 1910s were being mirrored in the events of the 2010s. Case(s) in point: rising income inequality, issues with immigration, the vilification of socialism, women's rights, Civil rights, voter suppression, marches for social justice - all these things happened in the 1910s and are happening again today. But one thing I did NOT expect to see, was this recent article from Civil Eats, outlining the struggle of onion farmers, particularly those practically in my own back yard in the black dirt region of Orange County, NY, as they deal with plummeting wholesale prices - so much so that a federal inquiry has been ordered. What. This is straight out of 1916 and my book research. Government inquiries and all. You see, in the winter of 1916/17, food prices had gone up exponentially and working class women in New York City, mostly Jewish women on the Lower East Side, staged food boycotts of a variety of produce, including onions, to protest prices that had doubled or tripled in a matter of weeks. Prices did lower eventually, but not before onions were virtually rotting in railroad yards and warehouses. Farmers in the black dirt region struggled to deal with the surplus and turned to other options as a means of potentially saving their quite perishable crop. Here are some excerpts from my book about the both sides of the situation: Pushcarts remained in service for the time being, however, and Jewish women in particular had had enough of rising prices. Mere months ago their husbands’ wages had bought plenty of vegetables with room for a shabbos chicken and other occasional luxuries. According to a New York Times investigation, February of 1917 left many families barely subsisting on coffee, tea, bread, and rice. Most could not afford potatoes, much less meat. Laborers who used to eat onion sandwiches every day for lunch could now not even afford onions. Wages had to be used for rent, wood or coal for heat, and clothing in addition to food. For many households, food was the one budget item with some wiggle room. But now their budgets were squeezed beyond bearing. Those making ten dollars or more per week were scraping by. Those making less were forced to rely on family members or charity to survive.[1] To working families, the fact that their circumstances had not changed but they suddenly could not afford even the cheapest of foods was not only a hardship, it was an affront to the promise of capitalism. Some families coped by taking on extra work; others coped by eating less or lower quality food. Some grew desperate as “investigators for the city’s charity department found people eating ‘decayed’ potatoes and onions,” although perhaps investigators’ definitions of “decayed” differed somewhat than those of the poor. For many, protest was the best coping mechanism. By February 20, 1916, the Jewish women of the Lower East Side, assisted to some extent by Socialist political groups, organized neighborhood boycotts to try to drive prices down. The violence with which these women enforced the boycotts—assaulting those who broke the boycott, destroying vegetable carts, and attacking storefronts—shocked Progressives and the general public alike.[2] By noon, the boycott had swelled its ranks with poor and working class women and their children who clamored at the gates of Mayor John Mitchel of New York City, holding up their babies and demanding bread. Mitchel refused to meet with them, suggesting that representatives meet with him the following day. The authorities, unable to solve the food price issue and at a loss when it came to dealing with violent and rioting women, did little except arrest and jail the rioters. Most of the women arrested in New York City were later broken out of jail by their free counterparts.[3] Perhaps inspired by the women of New York City, food boycotts and rioting quickly spread across the country. On February 21, riots broke out in Philadelphia; on February 22, in Boston. On February 23, newspapers reported that people in Alabama and Mississippi were near starvation as "for weeks only 6 per cent of the usual allotment of railroad cars” had been able to move food into the region. In New York City on February 22 and 23, there were poultry price demonstrations. In one week the price of poultry had risen from 20 or 22 cents per pound to as high as 32 cents per pound—a 45 percent increase. On February 25, 5,000 people “leaving a protest rally at Madison Square, marched upon the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, demanding food.” Demonstrators also attacked wealthy motorists. One driver, “fearing injury at the hands of the mob, put in high speed and went pell mell through the crowded street,” injuring at least one hundred women and some children. In Philadelphia, food riots resulted in one man being shot by the police and an old woman being trampled by a mob, while furious mothers declared a school strike. In Cincinnati, community leaders called for a boycott of butcher shops. In Chicago, settlement workers reported acute suffering among the city’s poor. High food prices and fuel shortages gave rise to “[r]umors of foreign influence,” which prompted a Justice Department investigation. The investigation later found “no plot” in the food boycotts, only hungry people.[4] The rioting and protests in New York continued on March 1, which the socialist daily paper New York Call called the “worst rioting” yet. Nearly one hundred people were arrested as grocery stores across the Lower East Side were attacked. On March 3, butchers stabbed a baby and an old woman in two separate protest incidents. In an effort to quell the boycotts and alleviate hunger, authorities tried a variety of ways to bring food into the city. Some Progressives tried to shift the diets of poor and working-class Americans to nutritionally equivalent but cheaper and more readily available substitutes, but to the boycotting women this was offensive. “We don’t want their oleomargarine. I could buy butter once on my husband’s wages – I don’t see why I shouldn’t have the same to-day,” said Mrs. Ida Markowitz at a protest. Other women felt the same—“Even two months ago it wasn’t so hard as it is today.” Other Progressive reformers tried to get their wealthy friends to “subscribe” to their efforts to replace middlemen with themselves – to personally buy up produce and have it shipped into the city to sell at below market costs, with the assurance that subscribers would get their money back, of course.[5] The biggest blunder by wealthy Progressives was perhaps that of George Perkins, head of New York City’s Food Committee, who “sent 14,000 pounds of smelt into the city on motor trucks, [but] angry East Side shoppers ‘who suspected Wall Street and did not want smelts, anyhow, mauled the sellers and returned some of the fish to their native element through open manholes.’” Dr. Haven Emerson, head of the New York City Health Department, nearly provoked another riot on March 3 when he told 2,000 East Side residents “to use milk instead of eggs and rice rather than potatoes and not to intrude their European habits into the United States.” An editorial in the New York Call, pointed out that high use of cheaper substitutes was far more likely to simply drive up the prices of said substitutes as demand increased. Many suspected that suggested substitutes were not only a deflection of the larger high cost of living problem, but also covert (and not so covert) attempts by Yankee Progressives to Americanize and assimilate the food habits of immigrant communities.[6] In New York, the boycotts and riots eventually worked. Or so it seemed. In the weeks between February 20 and March 11, pushcarts disappeared from the streets, vendors “slashed prices to save their stocks from spoilage . . . Onion shipments accumulated unsold at wholesalers’ wharves.” By March 11, potato prices had fallen from eleven cents to six cents per pound. But by March 25, New York State Agriculture Commissioner Charles Wilson reported that meat, bread, and vegetables like potatoes were likely to remain scarce, owing to a poor potato and vegetable crop in 1916 and encroachment on cattle range lands in the west. Although prices were dropping from their mid-winter highs, the high cost of living and food price problems remained fundamentally unresolved. [7] [1] “Food Problem Real to East Side’s Poor,” New York Times, February 25, 1917. [2] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 226; Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 258-259. [3] Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 255-285. [4] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 223-229; Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2008), 23; “No Plot in Food Riots,” New York Times, February 24, 1917. [5] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 228-238; As quoted in Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 262-263. [6] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 234-235. [7] Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 259; “Sees No Hope of Drop in Prices of Food,” New York Times, March 24, 1917. For the onion farmers, it was a different story. While their crops were rotting at warehouses, they were searching for alternatives to save the crop. From a different chapter in the book: One of the most popular topics of the OCFPB’s 1917 “Conservation Special” was the premise of grinding potato flour in the home and on the farm. Community dehydration plants and homemade kitchen driers were enthusiastically received, especially in the Pine Island, “black dirt” area where onion and potato farmers were hardest hit by boycotts and transportation issues.[1] Potato flour was being touted as a substitute for or additive to stretch wheat flour, which Herbert Hoover had asked housewives across the country to conserve through his “Wheatless Wednesdays” campaign. In her Erie Railroad Magazine article reporting on the “Conservation Special,” Gillian Bailey wrote, “That we brought encouragement and help to the large market growers is evident by the fact that we are expecting at least three commercial dryers to be run . . . and when these three huge machines are being run to their full capacity I shall feel that Orange county will be doing her bit.” [2] Indeed, there was a great deal of interest in installing community dehydrators all over Orange County. The mayor of Middletown, N.Y. was “so interested in the possibility of a local plant” that he coordinated with the Middletown Chamber of Commerce to discuss. Staff from a local farm belonging to the Department of Correction of New York City spoke with Mrs. Andrea about preserving produce like corn, beans, and tomatoes “until markets for them could be found.” Mrs. Andrea was the OCFPB’s at-large home economics expert who had published a book on food preservation through canning and later went on to publish another on dehydration and drying.[3] Individuals were also interested in dehydration. The OCFPB’s Mrs. M. C. Migel said that “a community dryer is to be installed on her estate at Monroe, N.Y., as an incentive to others. Mrs. H. D. Pulsifer, who owns the 700-acre Houghton farm, at Mountainville, N.Y., is another person who showed interest in the community dryer.” Port Jervis, too, showed a great deal of enthusiasm in the potential of a community dehydrating plant. In a letter to Mrs. Bailey about her impending magazine article, a representative from the Erie Railroad wrote congratulating her about the press coverage of the train, including this tidbit, “Port Jervis, you will note by reading the Union report, is deeply interested and its business men have taken up the question of a community dryer.”[4] Unfortunately for Gillian’s optimism, community dehydration plants did not take off in Orange County as planned. The Port Jervis Union recounted the decision, indicating that a large commercial dryer was too expensive. “After a long discussion, it was decided that Port Jervis and the adjacent farming territory was not large enough to support such a plant.” Indeed, although homemade dryers seemed popular and commercially made ones could be had for as “little” as five dollars, the big commercial dehydration plants proved out of reach for most communities. The narrow profits to be made on dehydrated vegetables just could not warrant the up-front expense. As the war wore on and agricultural production improved, the demand for dehydrated foodstuffs seemed to decline. Perhaps the length of time to dehydrate and the difficulty in reviving dehydrated vegetables, in particular, made the process less palatable to farm wives and individuals. Canning took less time, and the results were much easier to use – just heat and serve for most vegetables, and canned fruits could be eaten straight from the jar. The commercial market for dehydrated vegetables also did not seem particularly robust, and thus could not support the expense of large-scale dehydration.[5] [1] Bailey, “Waste Not, Want Not” Erie Railroad Magazine, 391; “Farmers Interested In Vegetable Drying,” Evening Telegram (New York), July 5, 1917, p. 4. The “black dirt” region of Orange County is a prehistoric peat bog where many a mastodon skeleton has been discovered. This land was sold to Bohemian and Polish immigrants by speculators in the 19th century who deemed it worthless, but the immigrants had experience with draining wetlands to make rich farmland. The topsoil in this region is still today up to 30 feet deep. Special horse shoes were developed to keep them from sinking as they plowed, and modern tractors must have dual tires and cannot be left in the fields overnight. [2] Gillian Webster Barr Bailey, “Waste Not, Want Not,” Erie Railroad Magazine 13, no. 7: 430. [3] “Preached Gospel of Dehydration to 7,000 Persons,” Herald (New York City), July 8, 1917. [4] Ibid.; Erie Railroad Company to Mrs. Bailey, July 9, 1917, Orange County Food Preservation Battalion Scrapbook 1917-1919, Archive, Museum Village, Monroe, NY. [5] “Chamber of Commerce Discussed Drying Plant – City and Community Not Large Enough To Support the Proposition,” Port Jervis Union, undated, Orange County Food Preservation Battalion Scrapbook 1917-1919, Archive, Museum Village, Monroe, NY. Of course, onion farming still happens in Pine Island and Chester and other black dirt towns, as mentioned in the Civil Eats piece. For more about the farming itself, check out this piece from the BBC. And, if you'd like to read the book chapters these excerpts are from, become a member of The Food Historian and you can read to your heart's content in the members-only section of the website. Join today or support us on Patreon. Longtime followers of this blog may have noticed that I keep moving the goalposts on book publication. That's because life, as it often does, has intervened in the past few years. So poor "Preserve or Perish" gets neglected, and I feel guilty about it. I'm hoping that 2020 will bring more stability, less stress, and more routine and free time. So of course, the book is at the top of the list! My primary goals for 2020 are thus: Write.My book, "Preserve or Perish," on food in New York State during WWI is nearly complete. Peer reviewers wanted more context, my editor wanted a chapter on propaganda, and I wanted to add recipes and make the academic text a little more approachable to the lay reader. But editing, an essential part of the writing process, is HARD. Especially when adding context means you have to go back and read (and take notes on) and condense and cite even more secondary source books. I am, however, probably most of the way there. I'm not sure what the final book will look like, as this one is ending up longer than expected, but I know that the finished product will be better for the time and attention. Setting a completion deadline for myself also usually works to kick in my "oh no I have a deadline let me work furiously and extremely efficiently to meet it" generally works. So fingers crossed. I also want to post more in this blog. Thank goodness for the scheduling function, so I can sit down and write a few posts at a time. But I also want to branch out in topics. I've loved the World War Wednesday series, but I want more time for historic recipes and cookbooks, too. Teach.I know a LOT about food history. I've been studying it, on a fairly regular basis, for over 15 years. And I want to share what I know, but the traditional college course is not really for me (also, adjuncts are treated terribly in academia). Which is why I'm in the process of developing a couple of online courses. I also want to get back into podcasting and/or make a few YouTube videos. Part of the online course process is creating online videos, so why not make a few shorts to post on YouTube? Organize.In the past few years I've acquired a LOT of vintage cookbooks. I've managed to organize some of them, but I have it on good authority that more are coming in 2020. So, that not only means organizing my library (again), but also cataloging what I have and digitizing a few gems to share. Community.This is a bonus resolution, in part because I think it will be so much fun. We've got a great group over on Facebook and my Patreon patrons delight me in more ways than I can say. But I'd like to develop a place for all us like-minded folks to be able to better communicate and spend time together. SO! To that end, I'd like your feedback! What do you think of these goals? I've made a little survey for you to take (only 4 questions long!) and help shape the future of The Food Historian. How About You?Do you have any 2020 goals related to food, history, or food history? Share in the comments!

A farmerette in a field near Syracuse, NY in her official uniform of jodhpurs, puttees, and tunic. Note the holes in the knees of her breeches. She appears to be forking clover hay. A farmerette in a field near Syracuse, NY in her official uniform of jodhpurs, puttees, and tunic. Note the holes in the knees of her breeches. She appears to be forking clover hay. One of the best things about being a historian is when the research leads you down new and unexpected paths. In editing and updating my book manuscript, I've been doing research on "farmerettes," also known as the Woman's Land Army of America. Farmerettes were young women, mostly white, middle- and upper-clsas teachers, shop girls, and college girls, who worked to prove the worth and strength of women by providing agricultural labor during the First World War. I hadn't originally planned to include much more than a mention of farmerettes, largely because Elaine Weiss did such a fantastic job chronicling the history of the Woman's Land Army of America with her book The Fruits of Victory. But the funny thing about life, and historical newspaper research, is that sometimes you come across a little tidbit that takes you in a whole other direction. My tidbit was a rumor about an original building used by the WLAA in Marlborough, NY. The building is still standing (for now - the owner may soon be developing the property, but there's a campaign to move it) but when I started researching "farmerette" and "Ulster County" a whole host of articles popped up and I realized something important - although the WLAA was founded in 1917, most of these articles were from 1919 and 1920. So I started doing a little more digging, and stumbled across this: The Farmerette Newsletter appears to be first published in January, 1919 (although numbers two and three are both from January, 1919, I have not been able to track down volume one, number one). The first article reads:

"The Secretary of Labor has approved an agreement which makes the Land Army a Division under the Department. He has said, in taking this step, that it will be well for us to play for greater activity next summer, and emphasizes the importance of training women in agriculture. In this action of the Government, there is not only a very welcome recognition of the work that has been done, but also a definite program. "It is no longer a war program; but our peace program still includes the feeding of the hungry in the Old World. We still have to "help Hoover," and Hoover has pledged to Europe twenty million tons of food in 1919. This will not be possible without more than normal farm labor. Therefore the Government has said that the Land Army is not to demobilize, but is to be directed as a part of the nation's service from Washington." What. The Woman's Land Army of America started out as an all-volunteer copycat of British organizations and was strongly tied to women's suffrage movements. And yet, by 1919, here it was partnering with and possibly even being subsumed by the Department of Labor, a fact that seems unlikely, but appears to be very true. This is what I love so much about food history - in this one primary source we have insight into the history of agriculture, women's suffrage, and the post-war labor shortage. The revelation that the Woman's Land Army of America coordinated with the Department of Labor puts a whole new spin on the movement, and illustrates the impact of the Great War on labor in America. Ultimately, the farmerette movement seems to have died out by the close of 1920, perhaps because agricultural labor was not exactly a lucrative endeavor for young women who expected more from life. At any rate, the later years of the farmerettes are going to join surplus food riots, labor shortages, agricultural advancements, and other post-war events and innovations in their own little chapter in Preserve or Perish. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed