|

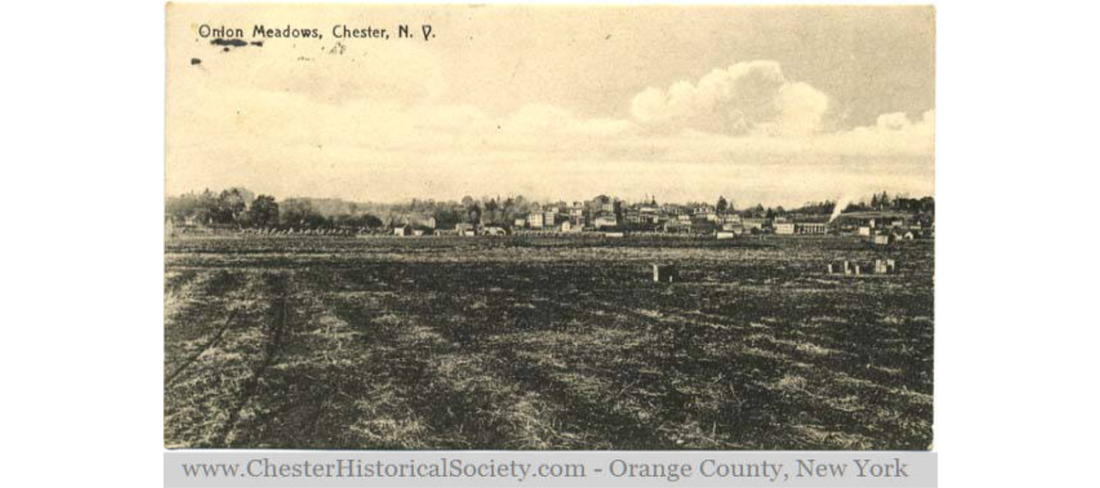

Okay folks. Here's where the history gets real. I've felt often in the last several years that the events of the 1910s were being mirrored in the events of the 2010s. Case(s) in point: rising income inequality, issues with immigration, the vilification of socialism, women's rights, Civil rights, voter suppression, marches for social justice - all these things happened in the 1910s and are happening again today. But one thing I did NOT expect to see, was this recent article from Civil Eats, outlining the struggle of onion farmers, particularly those practically in my own back yard in the black dirt region of Orange County, NY, as they deal with plummeting wholesale prices - so much so that a federal inquiry has been ordered. What. This is straight out of 1916 and my book research. Government inquiries and all. You see, in the winter of 1916/17, food prices had gone up exponentially and working class women in New York City, mostly Jewish women on the Lower East Side, staged food boycotts of a variety of produce, including onions, to protest prices that had doubled or tripled in a matter of weeks. Prices did lower eventually, but not before onions were virtually rotting in railroad yards and warehouses. Farmers in the black dirt region struggled to deal with the surplus and turned to other options as a means of potentially saving their quite perishable crop. Here are some excerpts from my book about the both sides of the situation: Pushcarts remained in service for the time being, however, and Jewish women in particular had had enough of rising prices. Mere months ago their husbands’ wages had bought plenty of vegetables with room for a shabbos chicken and other occasional luxuries. According to a New York Times investigation, February of 1917 left many families barely subsisting on coffee, tea, bread, and rice. Most could not afford potatoes, much less meat. Laborers who used to eat onion sandwiches every day for lunch could now not even afford onions. Wages had to be used for rent, wood or coal for heat, and clothing in addition to food. For many households, food was the one budget item with some wiggle room. But now their budgets were squeezed beyond bearing. Those making ten dollars or more per week were scraping by. Those making less were forced to rely on family members or charity to survive.[1] To working families, the fact that their circumstances had not changed but they suddenly could not afford even the cheapest of foods was not only a hardship, it was an affront to the promise of capitalism. Some families coped by taking on extra work; others coped by eating less or lower quality food. Some grew desperate as “investigators for the city’s charity department found people eating ‘decayed’ potatoes and onions,” although perhaps investigators’ definitions of “decayed” differed somewhat than those of the poor. For many, protest was the best coping mechanism. By February 20, 1916, the Jewish women of the Lower East Side, assisted to some extent by Socialist political groups, organized neighborhood boycotts to try to drive prices down. The violence with which these women enforced the boycotts—assaulting those who broke the boycott, destroying vegetable carts, and attacking storefronts—shocked Progressives and the general public alike.[2] By noon, the boycott had swelled its ranks with poor and working class women and their children who clamored at the gates of Mayor John Mitchel of New York City, holding up their babies and demanding bread. Mitchel refused to meet with them, suggesting that representatives meet with him the following day. The authorities, unable to solve the food price issue and at a loss when it came to dealing with violent and rioting women, did little except arrest and jail the rioters. Most of the women arrested in New York City were later broken out of jail by their free counterparts.[3] Perhaps inspired by the women of New York City, food boycotts and rioting quickly spread across the country. On February 21, riots broke out in Philadelphia; on February 22, in Boston. On February 23, newspapers reported that people in Alabama and Mississippi were near starvation as "for weeks only 6 per cent of the usual allotment of railroad cars” had been able to move food into the region. In New York City on February 22 and 23, there were poultry price demonstrations. In one week the price of poultry had risen from 20 or 22 cents per pound to as high as 32 cents per pound—a 45 percent increase. On February 25, 5,000 people “leaving a protest rally at Madison Square, marched upon the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, demanding food.” Demonstrators also attacked wealthy motorists. One driver, “fearing injury at the hands of the mob, put in high speed and went pell mell through the crowded street,” injuring at least one hundred women and some children. In Philadelphia, food riots resulted in one man being shot by the police and an old woman being trampled by a mob, while furious mothers declared a school strike. In Cincinnati, community leaders called for a boycott of butcher shops. In Chicago, settlement workers reported acute suffering among the city’s poor. High food prices and fuel shortages gave rise to “[r]umors of foreign influence,” which prompted a Justice Department investigation. The investigation later found “no plot” in the food boycotts, only hungry people.[4] The rioting and protests in New York continued on March 1, which the socialist daily paper New York Call called the “worst rioting” yet. Nearly one hundred people were arrested as grocery stores across the Lower East Side were attacked. On March 3, butchers stabbed a baby and an old woman in two separate protest incidents. In an effort to quell the boycotts and alleviate hunger, authorities tried a variety of ways to bring food into the city. Some Progressives tried to shift the diets of poor and working-class Americans to nutritionally equivalent but cheaper and more readily available substitutes, but to the boycotting women this was offensive. “We don’t want their oleomargarine. I could buy butter once on my husband’s wages – I don’t see why I shouldn’t have the same to-day,” said Mrs. Ida Markowitz at a protest. Other women felt the same—“Even two months ago it wasn’t so hard as it is today.” Other Progressive reformers tried to get their wealthy friends to “subscribe” to their efforts to replace middlemen with themselves – to personally buy up produce and have it shipped into the city to sell at below market costs, with the assurance that subscribers would get their money back, of course.[5] The biggest blunder by wealthy Progressives was perhaps that of George Perkins, head of New York City’s Food Committee, who “sent 14,000 pounds of smelt into the city on motor trucks, [but] angry East Side shoppers ‘who suspected Wall Street and did not want smelts, anyhow, mauled the sellers and returned some of the fish to their native element through open manholes.’” Dr. Haven Emerson, head of the New York City Health Department, nearly provoked another riot on March 3 when he told 2,000 East Side residents “to use milk instead of eggs and rice rather than potatoes and not to intrude their European habits into the United States.” An editorial in the New York Call, pointed out that high use of cheaper substitutes was far more likely to simply drive up the prices of said substitutes as demand increased. Many suspected that suggested substitutes were not only a deflection of the larger high cost of living problem, but also covert (and not so covert) attempts by Yankee Progressives to Americanize and assimilate the food habits of immigrant communities.[6] In New York, the boycotts and riots eventually worked. Or so it seemed. In the weeks between February 20 and March 11, pushcarts disappeared from the streets, vendors “slashed prices to save their stocks from spoilage . . . Onion shipments accumulated unsold at wholesalers’ wharves.” By March 11, potato prices had fallen from eleven cents to six cents per pound. But by March 25, New York State Agriculture Commissioner Charles Wilson reported that meat, bread, and vegetables like potatoes were likely to remain scarce, owing to a poor potato and vegetable crop in 1916 and encroachment on cattle range lands in the west. Although prices were dropping from their mid-winter highs, the high cost of living and food price problems remained fundamentally unresolved. [7] [1] “Food Problem Real to East Side’s Poor,” New York Times, February 25, 1917. [2] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 226; Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 258-259. [3] Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 255-285. [4] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 223-229; Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2008), 23; “No Plot in Food Riots,” New York Times, February 24, 1917. [5] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 228-238; As quoted in Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 262-263. [6] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 234-235. [7] Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 259; “Sees No Hope of Drop in Prices of Food,” New York Times, March 24, 1917. For the onion farmers, it was a different story. While their crops were rotting at warehouses, they were searching for alternatives to save the crop. From a different chapter in the book: One of the most popular topics of the OCFPB’s 1917 “Conservation Special” was the premise of grinding potato flour in the home and on the farm. Community dehydration plants and homemade kitchen driers were enthusiastically received, especially in the Pine Island, “black dirt” area where onion and potato farmers were hardest hit by boycotts and transportation issues.[1] Potato flour was being touted as a substitute for or additive to stretch wheat flour, which Herbert Hoover had asked housewives across the country to conserve through his “Wheatless Wednesdays” campaign. In her Erie Railroad Magazine article reporting on the “Conservation Special,” Gillian Bailey wrote, “That we brought encouragement and help to the large market growers is evident by the fact that we are expecting at least three commercial dryers to be run . . . and when these three huge machines are being run to their full capacity I shall feel that Orange county will be doing her bit.” [2] Indeed, there was a great deal of interest in installing community dehydrators all over Orange County. The mayor of Middletown, N.Y. was “so interested in the possibility of a local plant” that he coordinated with the Middletown Chamber of Commerce to discuss. Staff from a local farm belonging to the Department of Correction of New York City spoke with Mrs. Andrea about preserving produce like corn, beans, and tomatoes “until markets for them could be found.” Mrs. Andrea was the OCFPB’s at-large home economics expert who had published a book on food preservation through canning and later went on to publish another on dehydration and drying.[3] Individuals were also interested in dehydration. The OCFPB’s Mrs. M. C. Migel said that “a community dryer is to be installed on her estate at Monroe, N.Y., as an incentive to others. Mrs. H. D. Pulsifer, who owns the 700-acre Houghton farm, at Mountainville, N.Y., is another person who showed interest in the community dryer.” Port Jervis, too, showed a great deal of enthusiasm in the potential of a community dehydrating plant. In a letter to Mrs. Bailey about her impending magazine article, a representative from the Erie Railroad wrote congratulating her about the press coverage of the train, including this tidbit, “Port Jervis, you will note by reading the Union report, is deeply interested and its business men have taken up the question of a community dryer.”[4] Unfortunately for Gillian’s optimism, community dehydration plants did not take off in Orange County as planned. The Port Jervis Union recounted the decision, indicating that a large commercial dryer was too expensive. “After a long discussion, it was decided that Port Jervis and the adjacent farming territory was not large enough to support such a plant.” Indeed, although homemade dryers seemed popular and commercially made ones could be had for as “little” as five dollars, the big commercial dehydration plants proved out of reach for most communities. The narrow profits to be made on dehydrated vegetables just could not warrant the up-front expense. As the war wore on and agricultural production improved, the demand for dehydrated foodstuffs seemed to decline. Perhaps the length of time to dehydrate and the difficulty in reviving dehydrated vegetables, in particular, made the process less palatable to farm wives and individuals. Canning took less time, and the results were much easier to use – just heat and serve for most vegetables, and canned fruits could be eaten straight from the jar. The commercial market for dehydrated vegetables also did not seem particularly robust, and thus could not support the expense of large-scale dehydration.[5] [1] Bailey, “Waste Not, Want Not” Erie Railroad Magazine, 391; “Farmers Interested In Vegetable Drying,” Evening Telegram (New York), July 5, 1917, p. 4. The “black dirt” region of Orange County is a prehistoric peat bog where many a mastodon skeleton has been discovered. This land was sold to Bohemian and Polish immigrants by speculators in the 19th century who deemed it worthless, but the immigrants had experience with draining wetlands to make rich farmland. The topsoil in this region is still today up to 30 feet deep. Special horse shoes were developed to keep them from sinking as they plowed, and modern tractors must have dual tires and cannot be left in the fields overnight. [2] Gillian Webster Barr Bailey, “Waste Not, Want Not,” Erie Railroad Magazine 13, no. 7: 430. [3] “Preached Gospel of Dehydration to 7,000 Persons,” Herald (New York City), July 8, 1917. [4] Ibid.; Erie Railroad Company to Mrs. Bailey, July 9, 1917, Orange County Food Preservation Battalion Scrapbook 1917-1919, Archive, Museum Village, Monroe, NY. [5] “Chamber of Commerce Discussed Drying Plant – City and Community Not Large Enough To Support the Proposition,” Port Jervis Union, undated, Orange County Food Preservation Battalion Scrapbook 1917-1919, Archive, Museum Village, Monroe, NY. Of course, onion farming still happens in Pine Island and Chester and other black dirt towns, as mentioned in the Civil Eats piece. For more about the farming itself, check out this piece from the BBC. And, if you'd like to read the book chapters these excerpts are from, become a member of The Food Historian and you can read to your heart's content in the members-only section of the website. Join today or support us on Patreon.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed