|

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Food History Happy Hour tonight! We made a version of "Fruit Punch" from 1924, doctored with some spiced rum. We also discussed the history of tea, coffee, and hot chocolate, the use of tea in 18th century punch recipes and in the Temperance movement, the influence of coffee houses on politics and science, the gendering of these drinks, and the difference between high tea, low tea, and afternoon tea.

Old Fashioned Fruit Punch (1924)

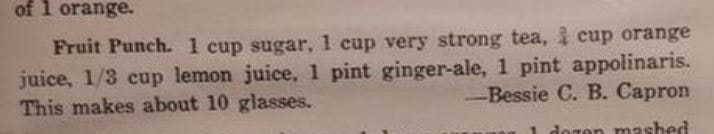

We often think of fruit punch today as the bright red sugary concoction of questionable flavor profile. Historically, fruit punches were non-alcoholic alternatives to highly alcoholic party punches popular in the 18th century. This version was probably inspired by Philadelphia Fish House Punch, a heady mix of citrus fruit, rum, brandy, cognac, and black tea. Here's the original recipe:

1 cup sugar 1 cup very strong tea 3/4 cup orange juice 1/3 cup lemon juice 1 pint ginger-ale 1 pint apollinaris (seltzer/club soda) This makes about 10 glasses. Here's the lovely alternative I made 1/2 cup sugar (this was VERY sweet, feel free to cut it to 1/4 cup) 1 cup very strong tea juice of 2 oranges juice of 1 lemon 1 cup ginger ale 1 cup seltzer 1/2 cup spiced rum Stir tea and sugar together over ice, then and the other ingredients and stir to combine. Serve cold in small cups. This is very good and very smooth. You could easily leave out the rum for a more Temperance-friendly non-alcoholic punch, or you can see other alternative punches, along with a history of Temperance, here. Next weekend I'm going to have another tea party, but in the meantime you can review the one from last weekend! So fun.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

0 Comments

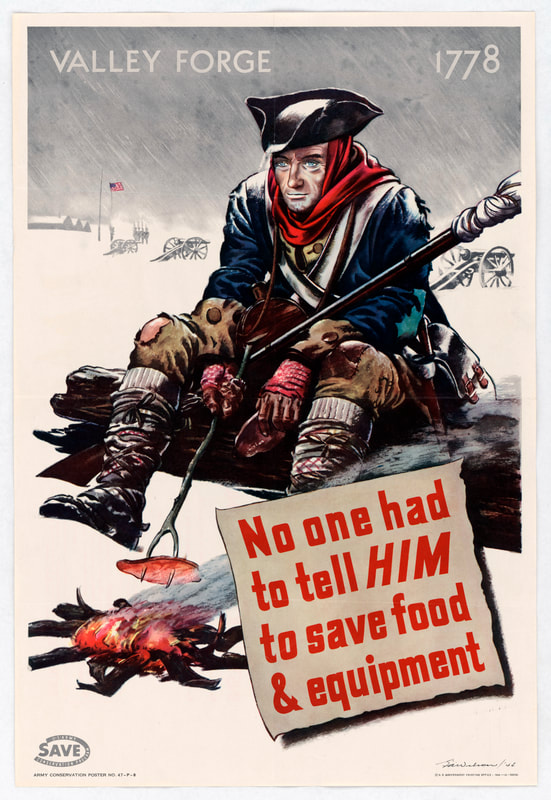

Hearkening back to the Revolutionary War was a common propaganda tactic in both World Wars. In this propaganda poster from World War II, soldiers were exhorted to save food and equipment by reminding them of Valley Forge - the winter cantonment of the Continental forces during the winter of 1777-78 which was famously (or infamously) difficult for the enlisted men, as clothing, housing, and food supplies were all very short. Despite the harsh conditions coming hard on the heels of a season of defeat against the British, General George Washington and Baron von Steuben rallied the men, beginning the formal training that would turn them into an effective force against the world's best military. In the poster image, a soldier with piercing blue eyes sits on a log next to a small campfire, enduring the falling snow. The shoulders of his blue regimental are torn, he has no greatcoat, one knee of his breeches is torn out, the other is patched. He wears a red scarf around his head and neck under his tricorned hat. The barrel of his musket is wrapped in fabric, probably to keep the snow out, and a knife or bayonet is in a sheath at his hip, next to his cartridge box. What appears to be a wooden canteen is around his neck. And on a forked stick he grills a thin piece of something over the fire - I suspect it is meant to be shoe leather, as he holds another piece in his hand, although it could simply be thin cuts of meat. The men famously boiled the leather of their shoes in an attempt to stave off starvation. What food was available was usually just meat and flour - no vegetables, no bread. These stories would have been well-known in the 1940s, part of the American mythology education that passed for history at the time. By comparing the soldiers of the American Revolution to the soldiers of the Second World War, this propaganda poster is reminding the men of the privileges they have in provisioning, and encouraging them to avoid waste, while hearkening back to the stamina and bravery of the men at the time. Other propaganda posters, like these, encouraged troops to conserve food because the folks back home were going without so they could have enough. While the nation today continues to recover from an enormous winter storm, with widespread power outages, it seemed apt to revisit Valley Forge. Read more about the food situation at Valley Forge in 1777-78. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

I've given a couple of talks on the history of macaroni and cheese now, and invariably someone brings up how homemade macaroni and cheese is so much better than Kraft. And I agree! While Kraft Dinner, invented in 1937, is definitely an important part of American history, you don't have to like it to appreciate it.

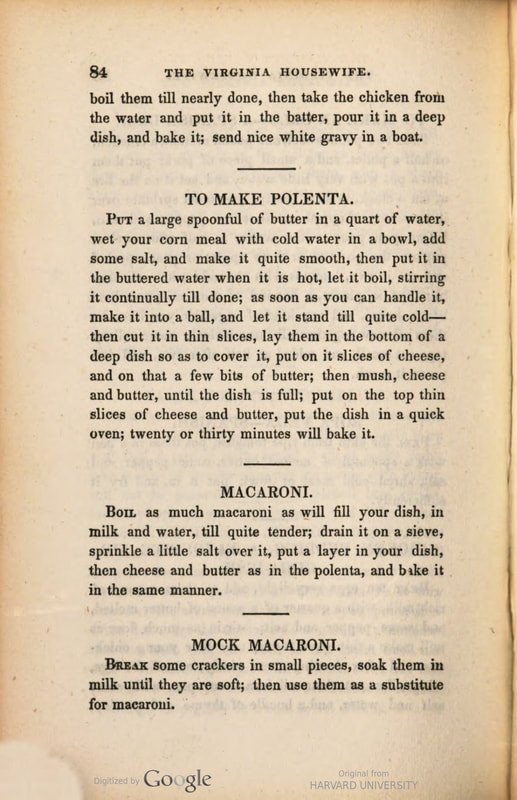

Macaroni and cheese dates back quite far in Western history. I think macaroni and cheese has its origins in ancient Roman shepherding and cacio e pepe - dried pasta, a little pasta water, very finely grated (fluffy!) pecorino romano cheese, and plenty of black pepper. But I like lots of black pepper on my macaroni and cheese, so perhaps I'm biased. By the 18th century, it's popular in Europe and James Hemings, enslaved chef to Thomas Jefferson, famously brings it back from his time in France. In fact, his recipe may have influenced cookbook author Mary Randolph, who was related to Jefferson, and whose macaroni and cheese recipe is one of the first to appear in an American cookbook. Macaroni and cheese is not particularly difficult to make. You can go super old-school and just layer butter and cheese, like Mary Randolph in The Virginia Housewife, one of the earliest references to macaroni and cheese in American cookbooks.

Or, you could emulate the later 19th century with a mornay sauce - that's bechamel maigre with some shredded cheese mixed in.

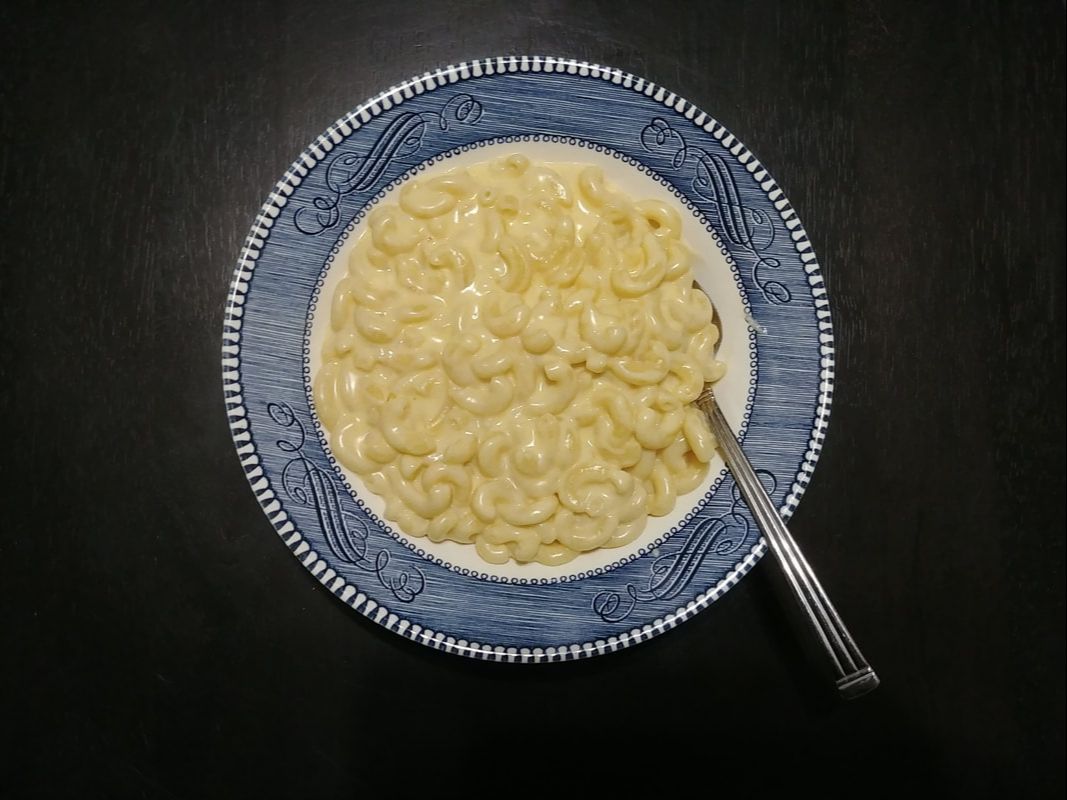

I'm firmly in the cheese sauce category, although I'm tempted to try the butter-and-cheese baked version, just to see how it measures up. Regardless, over the course of the 19th century, macaroni and cheese underwent a bit of a revolution, from expensive imported dish of the wealthy, to affordable railroad dining car, hotel, and cafeteria staple. For some, notably Black Americans, it also became an essential part of Thanksgiving and holiday tables - with recipes as varied as the cooks who made them. By the time we got halfway through the 20th century, it had also become a Depression-proof comfort food, beloved by children and people of all ages. Whether you're weathering a global pandemic, a bad day at work (or school), or just want to relive your childhood a bit, it's hard to go wrong with a steaming hot bowl of creamy, comforting, delicious macaroni and cheese. Better Than Kraft Macaroni & Cheese Recipe

There's not a lot of measuring in my kitchen, but the butter-to-flour ratio must always hold true - equal parts. You can increase or decrease the cheese to your preference, you can even mix cheeses. If you want something that tastes vaguely like Kraft, be sure to go with plenty of mild cheddar. Otherwise any kind of cheese, from smoked gouda to swiss to blue to cream cheese, are all fair game. You can halve this recipe if need be, but just make the whole pound of pasta. It makes decent leftovers. Here's what you'll need.

1 pound semolina pasta, any kind (I like elbows or medium shells) 1/2 cup butter (1 stick, salted or unsalted) 1/2 cup white flour at least 1 quart whole milk, maybe more 1-2 cups shredded cheese 1 tablespoon Dijon mustard (secret ingredient, optional) 1-2 teaspoons salt Your equipment needs are also basic. You'll need a 4 or 5 quart stockpot to boil the pasta, and a 2 quart pot to make the sauce, preferably one with a heavy bottom. Oh, and life will be a lot easier if you have one of these:

Okay, on to the instructions. First, grate your cheese. Don't use the pre-packaged store-bought shredded cheese - it's got anti-clumping agents (usually cellulose) that also prevent it from melting well.

Then, fill your 4 or 5 quart stockpot with at least 3 quarts of water and bring to a boil over high heat. Once boiling, add the pasta, a tablespoon of salt, give it a good stir to make sure it doesn't stick, and let it come back to a boil. Next, add your butter to the smaller saucepan and cook over medium heat until the butter is melted and bubbling. When the butter makes a sizzling noise, quickly whisk in the flour, making sure there are no lumps. And then, the important part, let the butter and flour mixture cook for at least 30 seconds, stirring occasionally. If you don't cook your flour, your sauce will be pasty. Yuck. There's a fine balance between golden cooked mixture and browned roux, though, so just keep an eye on it. Once your roux is cooked, start adding whole milk, a cup or so at a time. Whisk and allow to thicken between additions. After you've added a few cups of milk and the sauce is thickening up again, add your shredded cheese and Dijon mustard, and whisk thoroughly until the cheese is melted into the now very thick sauce. Then add more milk and whisk vigorously again. Keep adding milk until your saucepan is at least 2/3 if not 3/4 full. Meanwhile, your pasta has been boiling. You should check it occasionally to test doneness - the pasta should be soft but not soggy. Taste a piece each time. When done, drain and return to the cooking pot. Once your cheese sauce is thickened up enough to nicely coat a spoon, taste for salt and add, 1 teaspoon at a time. You want your sauce to be quite salty, as the pasta will be bland and absorb flavor. Once you're satisfied (always better to undersalt - you can add more at the table), pour the cheese sauce into the stockpot with the pasta and stir well. If the sauce seems a little liquidy, let it rest on the pasta for a few minutes. The pasta will absorb much of the liquid and thicken the sauce. Serve hot with extra salt for those who like it very salty (like me), and plenty of black pepper. Feel free to also top it with more cheese, chopped tomatoes, sliced scallions, caramelized onions, crumbled bacon, sausage, steamed broccoli, or anything else that strikes your fancy.

If making the cheese sauce and boiling the pasta at the same time seems tricksy and too much multi-tasking, boil and drain your pasta first, and then make the sauce. You'll feel better if you can give it your full attention, without getting distracted.

And there you have it - a macaroni and cheese recipe that is tastier than Kraft, nearly the same speed (start to finish is about 30 minutes), and almost as cheap. Do you have a favorite way you like your macaroni and cheese?

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

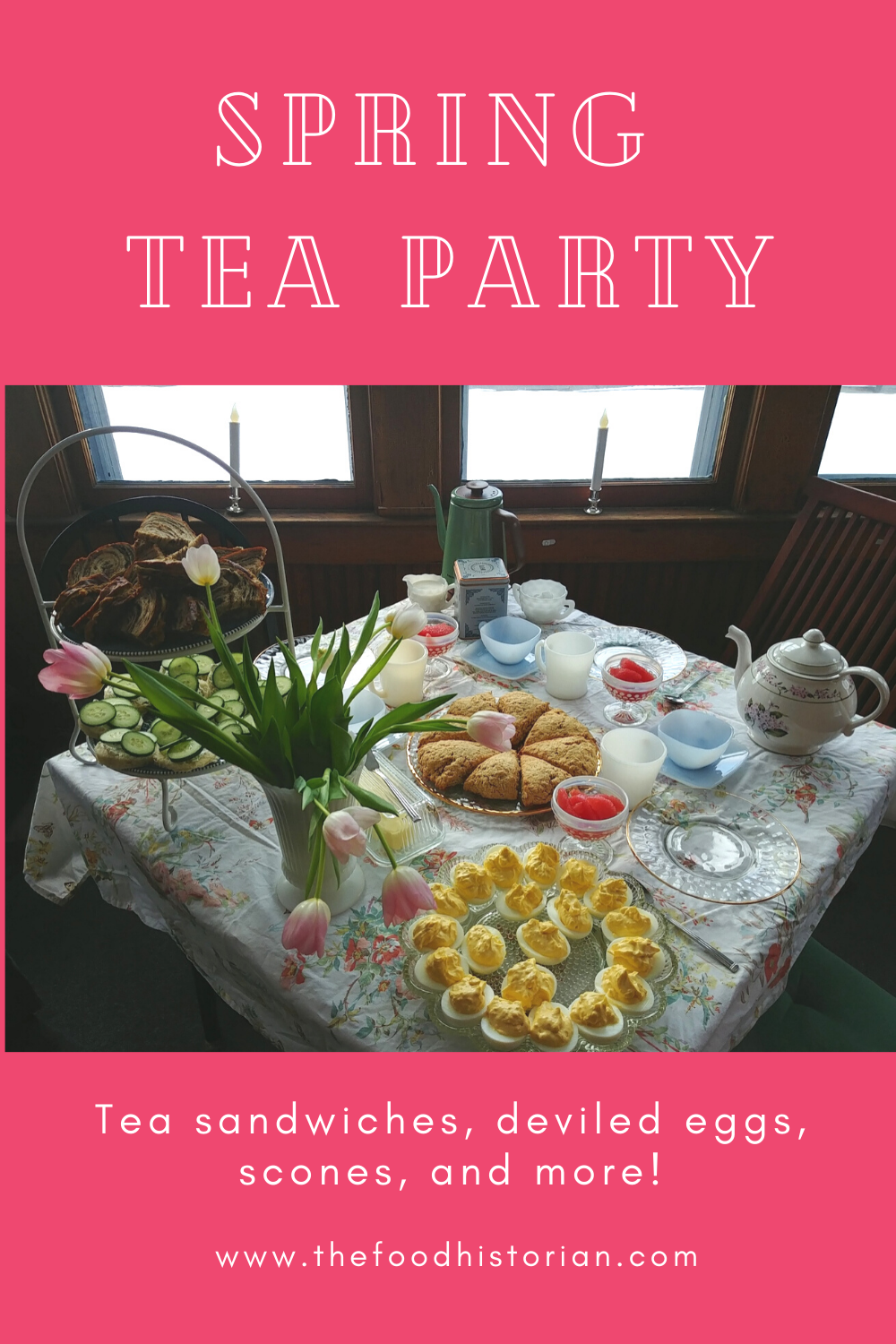

I love winter, don't get me wrong, and the frequent snowstorms and squalls we've been having here in New York have actually lifted my spirits more often than not. I vastly prefer fluffy white snow and prettily iced trees to muddy brown landscape and grey days. That being said, sometimes you just need to brighten your day, and this was exactly the little escape I needed. I spent the morning cooking and baking, a friend brought cookies and tulips, and we sat down to a delightful tea party, complete with my new favorite electric tea kettle. It was an excuse also to use some of my extensive collection of vintage glassware. I didn't match, but that was okay. Who can say no to hobnail compote dishes and Charm teacups?

Vegetarian Spring Tea Party Menu

Deviled Eggs

Lentilwurst Sandwiches with Mustard on Pumpernickel Cucumber Sandwiches With Herbed Cream Cheese on White Ruby Red Grapefruit Sections in Light Syrup Oatmeal Nutmeg Scones Citrus Yogurt Olive Oil Cake Chocolate Chip Cookies Hot Cocoa Assorted Tea with Cream and Sugar

I seriously considered making Earl Grey madeleines, and maybe cream biscuits with assorted jams, but with only three of us, this was plenty. We remarked on the funny thing about tea parties is that everything is fairly small, so it doesn't seem like much food, but it certainly fills you up quickly!

The menu was fairly easy. Our friend brought the cookies, the grapefruit was pre-sectioned from the refrigerated produce section of the grocery store. The most involved recipe was the citrus yogurt olive oil cake, which was okay, but not as nice as I had hoped, so I'm not going to include the recipe here. I made this tea party vegetarian in part because our friend is vegetarian, but also because vegetarian food just seems a bit lighter and more appropriate for a tea party. You can satisfy even the heartiest appetite with lentilwurst sandwiches - the mushroom/lentil mixture really does smell and even taste like sausage, thanks to the mix of herbs and spices. I first made lentilwurst back for our White Christmas themed party, and I've made it several times since. Cucumber Sandwiches

What is a tea party without cucumber sandwiches? I went extra-fancy here and cut rounds out of the centers of soft white sandwich bread (the bakery kind, not the pre-sliced kind). Frankly, it didn't make a lot of rounds, so I left these open-faced. I'm saving the outer scraps for bread pudding later this week. The rest of the recipe is simple. You'll need:

1 package neufchatel cream cheese 2 scallions dried dill weed a tablespoon or two of milk, cream, or buttermilk 1 English (or burpless/seedless) cucumber white bread rounds Soften the cream cheese at room temperature. Thinly slice the scallions, white and green parts, and add to the cream cheese with the dill weed and liquid. With a fork, mash the lot together until well mixed. Spread onto the rounds of bread and top with thin slices of cucumber. If you want to be extra fancy, you could garnish with fresh dill or chives. The bread will dry out as you let it sit out, so try to do these sandwiches at the last minute, or cover and refrigerate them. Deviled Eggs Recipe

Deviled eggs are one of my favorites, but I find most deviled eggs that other people make to be rubbery and bland. There are three tricks to deviled eggs - don't overcook the eggs, boil the eggs the same day you plan to serve them, and make the yolk filling smooth, creamy, and generous.

12 large eggs 1/4 cup mayonnaise 1/4 cup sour cream 2 tablespoons Dijon mustard In a large pot, cover your eggs with cold water by several inches. Bring pot of cold water to a boil over high heat and let boil for 1-2 minutes. Then turn off heat, set a timer for 15 minutes, and let eggs continue to cook as the water slowly cools down. When the 15 minutes are up, remove the eggs to a bowl of ice water to stop cooking and cool down. Peel the eggs (crack them under water for easiest peeling), halve them, and remove the yolks. With a fork, mash the yolks finely until there are no chunks left and the yolk mixture is powdery. Then add 2 tablespoons Dijon mustard, and 1/4 cup each mayo and sour cream. Mix well. If the mixture seems dry, add another spoonful of mayo and sour cream, until the yolk mixture is fluffy, but not runny. Fill the eggs generously, in the hollow left by the yolk and pile some more on top. I just use a spoon and dollop, but you can fill a pastry bag or a plastic sandwich bag with the end cut off if you want something a little more polished-looking. If desired, garnish with paprika, black pepper, and/or chopped chives, but I like mine plain. Keep cool until ready to serve, and watch them fly off the tray. Oatmeal Nutmeg Scones

Scones are another essential part of a tea party. These are my absolute favorite recipe, straight from the eminent Dorie Greenspan. I didn't make too many changes, except halfway through the recipe I realized I only had room temperature butter. Thankfully, my husband reminded me of the several pounds of butter in our chest freezer, so instead of cutting in cold butter like the recipe calls for, I grated frozen butter and mixed that in, which worked well. These scones have a nutty, toasty, nutmeg-y flavor and using fresh-grated nutmeg really makes a difference, although you shouldn't use quite as much as pre-ground nutmeg

1 egg 1/2 cup cold buttermilk 1 2/3 cup all-purpose flour (I used white whole wheat) 1 1/3 cup old fashioned rolled oats 1/3 cup sugar 1 tablespoon baking powder 1/2 teaspoon baking soda 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/4 teaspoon nutmeg 10 tablespoons cold, unsalted butter (1 stick, plus 2 tablespoons) Preheat the oven to 400 F. In a small bowl, whisk together the egg and oatmeal. In a larger bowl, whisk all dry ingredients together, than cut in butter (or used grated frozen butter). Add egg mixture and toss with a fork until mostly combined. Knead a few times until the remaining flour is absorbed, then pat into a round and cut into wedges. Bake 20-22 minutes or until golden. Cool for a few minutes before serving. Serve warm with plenty of salted butter. Perfect Tea

The one lovely thing about using an electric kettle for tea is you can have the kettle right at the table, which is what we did. Cooking at table with electric appliances was common in the 1930s and '40s, especially at breakfast. It was fun to be able to recreate that fashion today! Plus, being able to reheat the water right at the table certainly made a difference in refills.

In all, this teensy little party was super fun, and I'm definitely having a tea party again! Something about getting out the fancy dishes, fresh flowers, a candle or two, an assortment of tempting little treats, and plenty of hot tea makes everything better. Plus I have plenty of other recipes to share. So many, in fact, I'm considering writing a little tea party cookbook. Would you be interested if I did?

Have you ever had a tea party? Do you have favorite tea cups and dishes? Tell us in the comments!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

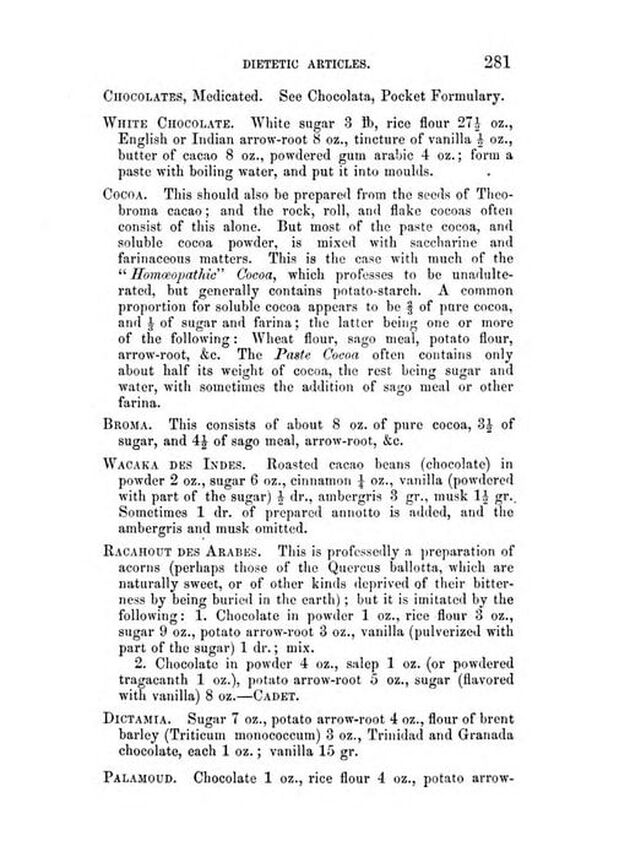

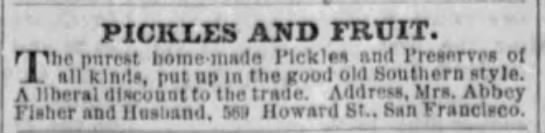

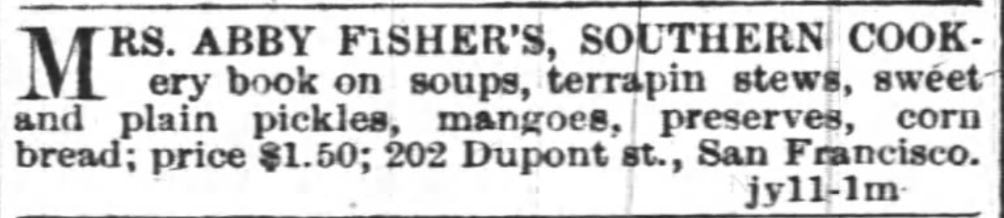

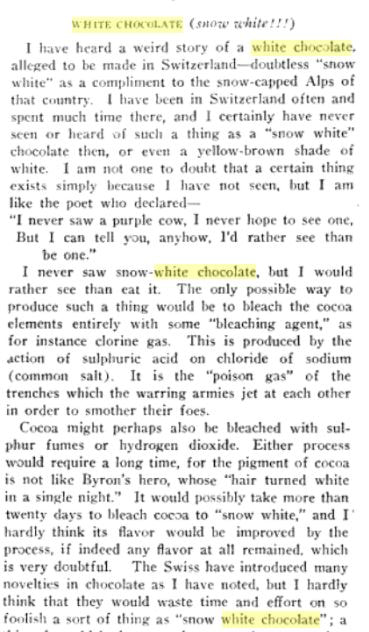

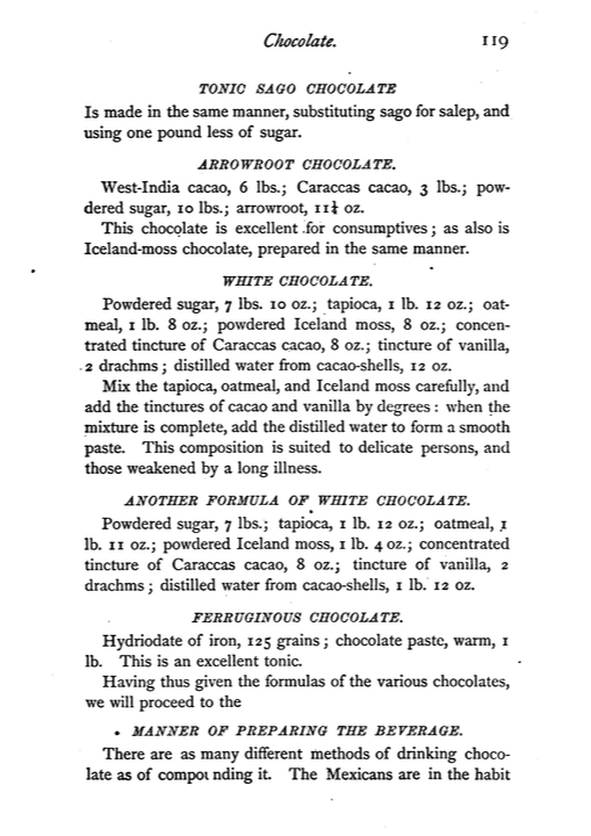

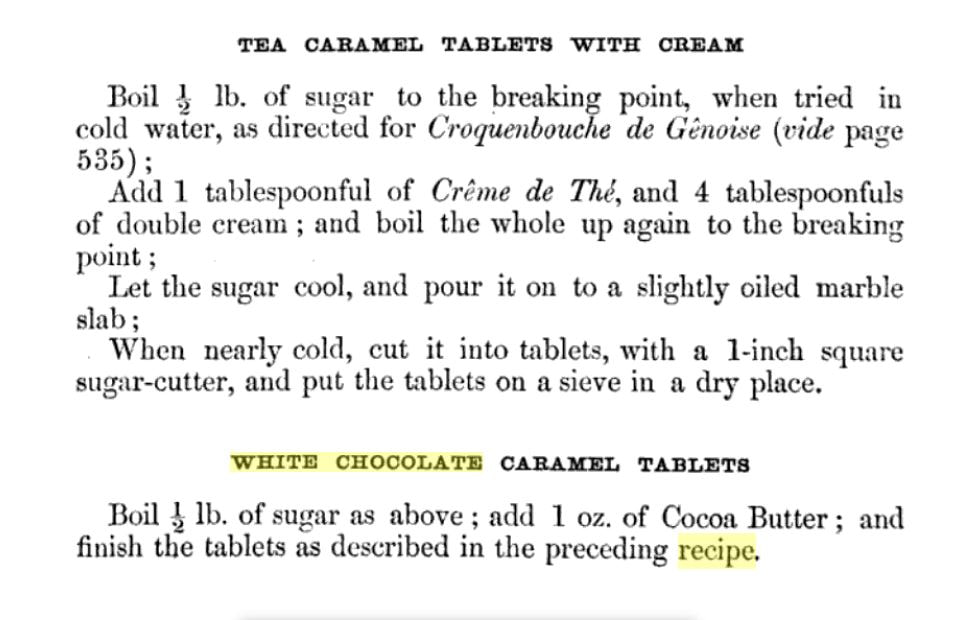

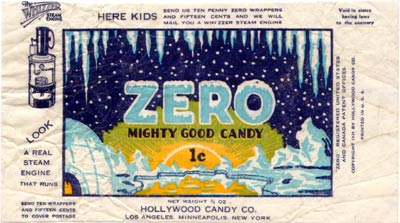

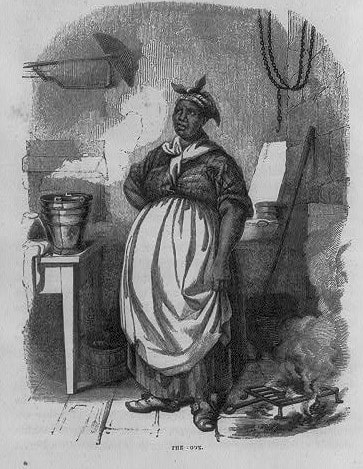

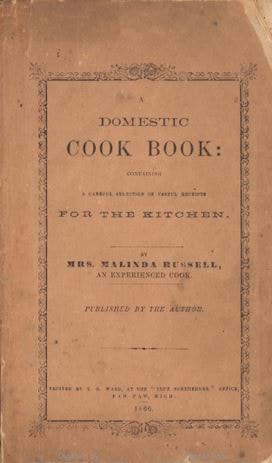

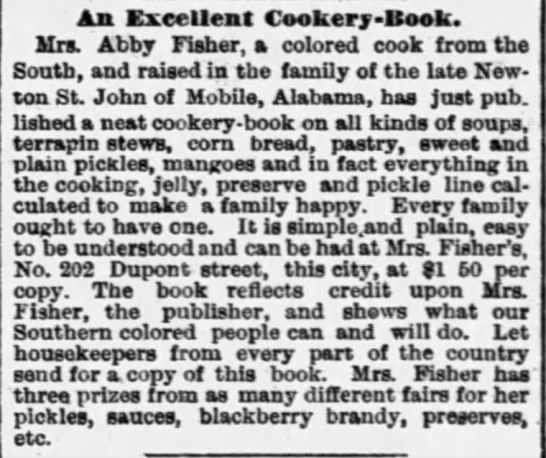

I've done several talks now on the history of hot chocolate, and in the slide on white chocolate, someone expressed skepticism about the fact that Nestle invented white chocolate in the 1930s, although that is the current consensus on the internet. For the Nestle claim - sources differ. Some say they were manufacturing it as early as 1930. Others say the introduction of the Galak bar (known as the Milkybar in the UK) in 1936 was the first. Still others claim it wasn't really white chocolate until the 1948 Alpine White Bar, which contained almonds. This article indicates that Nestle's research into a coating for a children's vitamin was what birthed white chocolate. Still, it did seem a little unusual that white chocolate was developed so late (even though milk chocolate wasn't really a thing until the 1890s). So I did a little digging. There wasn't a whole lot out there. Most of the hits were for the words "white" and "chocolate" that just happened to be next to each other. I got excited by a reference to "white chocolate cake" from the 1870s, but that turned out to just be a white cake with chocolate frosting. But then, I started to find some interesting tidbits. White Chocolate Skepticism, 1916First, I found this little snippet from the December, 1916 issue International Confectioner, in an article entitled, "Chocolate a la Noisette, Part II" by T. B. McRobert. In this section, McRobert expresses deep skepticism that the Swiss have invented a "snow white chocolate," and speculates that they bleach it with chlorine gas, sulphur [sic] fumes, or hydrogen dioxide, rendering it nearly inedible. He ends the article with the comment, "Certainly we hear some queer and weird stories from Europe these war times, and perhaps the 'snow white' chocolate is one of these war time yarns. Certainly 'snow white' chocolate is never likely to be any howling success in this country, if in fact such a thing could ever be made here and comply with our food laws, which is more than doubtful." I did find another reference, several years later, in the 1923 Encyclopedia of Food by Artemis Ward. In the entry for "Cocoa-Butter," the main text is followed by this little intriguing sentence - "Swiss 'white chocolate' - apart from milk-chocolate types - is cocoa-butter sweetened either with sugar or with sweet chestnut-meal." A tantalizing snippet, unreadable in full (thanks, Google Books), indicates this description in Food Industries Manual published in 1931, on page 142: "White chocolate is manufactured from sugar, milk powder or condensed milk, and cocoa butter, and the flavour of chocolate is dependent upon the cocoa butter content. Accordingly a very strong cocoa butter is used in the manufacture ..." and that's all we get! Still, we're definitely pre-dating the Nestle story. And then there was this strange little find. Strange White Chocolate, 1870sThe dessert book: a complete manual from the best American and foreign authorities. With original economical recipes by a Boston lady, published in 1872. The strange recipes listed above, including two for "white chocolate" appear to be recipes designed more for confectioners or pharmacists than the home cook. Apparently designed for invalids or "delicate persons," the mixture of tapioca, oatmeal, and Iceland moss, flavored with "tinctures of cacao" and vanilla and mixed to a paste with "distilled water from cacao shells" is a far cry from mixing cocoa butter with sugar and milk solids, which is what we normally expect white chocolate to be. A similar recipe shows up in a druggist's recipe book from 1871.  A recipe for white chocolate calling for rice flour, cocoa butter, and gum arabic. From "The Druggist's General Receipt Book: Containing a Copious Veterinary Formulary : Numerous Recipes In Patent And Proprietary Medicines, Druggists' Nostrums, Etc. : Perfumery And Cosmetics : Beverages, Dietetic Articles, And Condiments : Trade Chemicals, Scientific Processes, And an Appendix of Useful Tables," by Henry Blakely and published in 1871. The Druggist's General Receipt Book: Containing a Copious Veterinary Formulary : Numerous Recipes In Patent And Proprietary Medicines, Druggists' Nostrums, Etc. : Perfumery And Cosmetics : Beverages, Dietetic Articles, And Condiments : Trade Chemicals, Scientific Processes, And an Appendix of Useful Tables by Henry Blakely and published in 1871, has a white chocolate recipe very similar to the one from "A Boston Lady." A mixture of white sugar, rice flour, arrowroot powder, vanilla, cocoa butter, and gum arabic, mixed with boiling water and molded, the resulting confection was likely a chewy one. White Chocolate Caramel Tablets, 1869The Royal Cookery Book (le Livre de Cuisine) by Jules Gouffé, Alphonse Gouffé (1869) revealed this interesting recipe: White chocolate caramel tablets were probably a type of chewy caramel, although it's difficult to say, given the recipe. Boiling sugar to the "breaking point" indicates possibly hard crack stage, in which case the tablets would be more like toffee or a hard caramel candy, rather than the soft white chocolate we are used to. The Broma Process, 1865Invented around 1865 by a worker at the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company, the broma process involves placing roasted cocoa beans in a bag just above room temperature to allow the cocoa butter to drip out. The remaining cocoa beans could then be processed into cocoa powder. But what to do the with cocoa butter? Much of it was processed back into bar chocolate, making it richer than 100% cacao. But I think the surplus of cocoa butter from the cocoa powder process meant that people were more interested in trying out different types of chocolate, like white chocolate. The timeline certainly matches the above findings of pre-1930s white chocolate. The Zero Bar, 1920One last candy was niggling at the back of my head - the Zero Bar, first introduced in around 1920 as the "Double Zero Bar" by the Hollywood Brands company, based in Minneapolis, MN. In 1934 the name was changed to "Zero Bar" and the wrappers have always brought to mind chilly temperatures, which was by design. A caramel nougat with almonds and enrobed in white fudge, this candy bar appears to be one of the earliest commercial applications of white chocolate. Today, the Zero Bar is still manufactured by the Hershey Company, although it can be difficult to find in stores. White Chocolate ConclusionsWhen all is said and done, Nestle still appears to be the first company to market solid white chocolate on a commercial scale, although the Zero Bar clearly predates the Milkybar/Galak by over ten years and the Alpine White (first introduced in 1948) by nearly twenty. I personally enjoy white chocolate, and the Zero bar was a childhood favorite of mine, although I know many people think white chocolate is inferior to the kind including the whole bean. But I'm not sure I enjoy it quite as much as these Alpine White television commercials would have us believe. Do you like white chocolate? Do you have a favorite candy bar? Let me know in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Throughout the 19th century, white women used their domestic assets to pick up the slack left by disabled or deceased husbands - homes became boarding houses and tea rooms and domestic skills were translated into magazine articles and cookbooks. But free Black women in the 19th century did not have as many assets. And even when they did, these assets were often taken from them, and a racist and sexist judicial system gave them little recourse to recover property. Enslaved women freed by the Emancipation Proclamation had their freedom, but little else. The promised 40 acres and a mule never materialized. Despite these often difficult starts, many free and formerly enslaved women of color used their wits and skills to make their own way in the world. Often relegated to service jobs in households, many women created their own small businesses to avoid working for wages - tea rooms, boarding houses, laundries, seamstress and millinery shops, catering, etc. Most of these jobs had low startup costs and could be done from home, allowing for the care of children and family members. Many women also worked as professional cooks for taverns and hotels, a job that held more promise of profit and respect than working in a private household. The vast majority of women working in these fields remain hidden from history - unnamed and un-written-about. But some women of color have managed to make their mark on food history. Here are a few of their stories. Anne Northup - Twelve Years AloneAnne Northup was my first real encounter with the stories of adversity and perseverance many Black women faced throughout the 19th century. I attended a special program at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City with a historic dinner recreated by The Food Griot - Tonya Hopkins. Anne Hampton was born in 1808 in upstate New York. A free woman of color, she married Solomon Northup in the 1820s and in 1834 they sold their farm and moved to Saratoga. Solomon often worked as a fiddler and Anne worked as a cook and kitchen manager at hotels in the spa resort town. She was working at the Pavilion Hotel in Saratoga when she met wealthy white New Yorker Eliza Jumel in 1841. Divorcee/widow of Aaron Burr, Madame Jumel convinced Anne to come south and serve as a cook in her household. Anne sent her eldest daughter Elizabeth to Manhattan with Jumel, but waited until later in the year to come south herself, likely finishing out the busy tourist season. Earlier that summer of 1841, Anne's husband Solomon had answered an advertisement looking for musicians for a job in Virginia. An accomplished violinist, Solomon had answered the advertisement and traveled south. He was captured and sold into slavery, spending the next twelve years enduring brutal conditions on a Louisiana sugar plantation. Anne was left to fend on her own. After a year in Eliza Jumel's household, Anne and some (but not all) of her children returned to Saratoga, where they stayed until 1850, when they moved to Glens Falls and Anne continued her hotel work. They were not reunited with Solomon until 1853. He wrote a book about his experiences - Twelve Years a Slave. We lose track of Solomon Northup in the 1860s and his death date is unknown, although Anne and her children continue to live in New York. To learn more about the Northup family, read this excellent account by historian David Fiske. Anne Northup died on August 8, 1876 in Moreau, New York. Although she leaves behind no documentation of the food she cooked, given her positions in fashionable resort town hotels and wealthy households, she was likely very skilled in a variety of foodways. To me, she represents how many free women of color made their way in the world on the strength of their cooking skills, even in the face of extraordinary adversity. Malinda Russell & Her Union PrinciplesIn 2000, Jan Longone ran across a slim, crumbling cookbook wrapped in brown paper at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where she is curator of American culinary history. That cookbook, A Domestic Cookbook, published in 1866 by a woman named Malinda Russell, turned out to be the earliest known cookbook published by an African American woman. The cookbook has since been digitized, and when I read it for the first time the other day, I was struck by the incredible hardship Russell had to overcome in her life. In the autobiographical account that explains why she wrote the cookbook, Russell recounted the many setbacks in her life. Born free in Tennessee, at age 19 she set out to emigrate to Liberia, a promise of life free from the racism and oppression that continued to plague free Black communities in the North. But along the way, she was robbed by someone from her party, and was forced to stay in Virginia, where she made a living as a cook and a nurse. There, she married Anderson Vaughn, and they had a son together, but Vaughn died just four years later, leaving Russell a widow with a handicapped son. She moved back to Tennessee and opened a boarding house in a town that featured springs as a tourist attraction. She later opened a pastry shop in that same down and had saved up a sum of money to support herself and her son. But in early 1864, she was attacked and robbed by a "guerrilla party," likely Confederate soldiers. She and her son fled Tennessee during the height of the Civil War. Although Tennessee was a Union state, its proximity to the border meant it was not safe for Russell. She made her way to Michigan, enduring several attacks along the way, and went on to start over, again, in a new state. In May, 1866, she published A Domestic Cookbook. She closed her introduction stating that she hoped the sale of the cookbook would help her raise funds to return to Tennessee and reclaim some of her lost property when peace was restored. We do not know if she ever made it home to Tennessee, or really much else about her at all, although Jan Longone has worked to find more about her. According to Russell herself, "I have learned my trade of Fanny Steward, a colored cook, of Virginia, and have since learned many new things in cooking." She also indicated her cookbook was organized along the lines of Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife (1824). Malinda Russell reset much of the conventional wisdom about Black cooking heritage at the time it was rediscovered. But her cookbook is not much different from any other cookbook of the period - reflecting her experience as a boarding house owner and cook, cooking for the public and likely for audiences diverse in race and socioeconomic status. It also knows its audience, consisting largely of dessert and preserves recipes. These were commonly featured in published cookbooks because they were more complex than the everyday cooking of meat and vegetables and less likely to be familiar to ordinary cooks. Her cookbook contains everything from the humble "Baked Indian Meal Pudding" and 'Sliced Sweet Potato Pie," to the exquisite "Floating Islands" and "Charlotte Russe." For me, the most striking thing about Russell is not the content of her cookbook, but rather the fact that it exists at all - a testament to her difficult life and the grit she used to persevere. What Abby Fisher Knew "Pickles and Fruit. The purest home-made Pickles and Preserves of all kinds, put up in the good old Southern style. A liberal discount to the trade. Address, Mrs. Abbey Fisher and Husband, 569 Howard St. San Francisco." Advertisement from the December 13, 1879 issue of "The Placer Herald," published in Rocklin, CA. Unlike Anne Northup and Malinda Russell, Abby Clifton was born into slavery in 1831 in South Carolina to a white father and an enslaved mother. It is unclear when gained her freedom, but by 1860 she had moved to Alabama and married Albert Fisher. In 1877, they emigrated to California and by 1880, Abby and Albert were in San Francisco, where the 1880 Census listed Abby as a "cook" and Albert as a pickle and preserve manufacturer. But this attribution was likely due to sexism common among census takers. In reality, it was Abby who was manufacturing pickles and preserves - as listed in an 1882 San Francisco directory. Albert was listed as a porter. Abby leveraged her expertise in pickles and preserves to reach the highest echelons of San Francisco society. She was awarded a diploma at 1879 Sacramento State Fair. At the 1880 San Francisco Mechanics Institute Fair, she won a bronze medal for her pickles and preserves. Although she and Albert could not read or write, in 1881 she published the cookbook, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. with assistance from white friends who helped her translate and transcribe her memorized recipes into cookbook format. The book does not contain just pickles and preserves, although they and her famous blackberry cordial certainly make a showing. The title inclusion of "Old Southern Cooking" is certainly apt, given recipes for "Maryland Beat Biscuit," "Plantation Corn Bread," "Ochra Gumbo," "Creole Chow Chow," "Sweet Potato Pie," and "Peach Cobbler." But it also includes typical British-American foods popular in the Northeast and throughout the United States, including "Sally Lund" bread, "Jumble" cookies, "Sauce for Suet Pudding," "Rhubarb Pie," (rhubarb grows poorly in the South, needing below freezing temperatures), three different kinds of "Sherbet," "Yorkshire Pudding," and "Terrapin Soup." In short, her cooking is more representative of broad American style cooking of the period, with some Southern flavor, rather than stereotypically "Southern" (i.e. Black) cooking. The interest in Southern cooking, as evidenced by the marketing of her book, was likely part of a reaction to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Historian Megan Elias has written about "Lost Cause cookbooks" in which white Americans romanticized the "good old days" of slavery and subservient Black folks with "magic" cooking skills. It is possible that Abby Fisher's cookbook was swept up in the wave of racist nostalgia. But it is also possible that Abby's cookbook was simply a reflection of the interest in California residents in the cuisines of many newly arrived emigrants of all cultures and backgrounds. This seems to be the case in one announcement, published in the San Francisco Examiner on July 11, 1881. It reads: "An Excellent Cookery-Book. "Mrs. Abby Fisher, a colored cook from the south, and raised in the family of the late Newton St. John of Mobile, Alabamaa, has just published a neat cookery-book on all kinds of soups, terrapin stews, corn bread, pastry, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes and in fact everything in the cooking, jelly, preserve and pickle line calculated to make a family happy. Every family ought to have one. It is simple and plain, easy to be understood and can be had at Mrs. Fisher's, No. 202 Dupont street, this city, at $1.50 per copy. The book reflects credit upon Mrs. Fisher, the publisher, and shows what our Southern colored people can and will do. Let housekeepers from every part of the country send for a copy of this book. Mrs. Fisher has three prizes from as many different fairs for her pickles, sauces, blackberry brandy, preserves, etc." Although we may never know how many copies Abby sold, the cookbook seemed to garner positive reviews. For several weeks in 1881, she (or the publisher) advertised it in the Oakland Tribune (see below).  "Mrs. Abby Fisher's, Southern Cookery book on soups, terrapin stews, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes, preserves, corn bread; price $1.50; 202 Dupont st., San Francisco. jy11-1m." Advertisement for Mrs. Fisher's cookbook in the "Oakland Tribune," published July 11, 1881, but running for several weeks prior and after. In the 1890 San Francisco directory, "Mrs. Abbie Fisher" was still listed as "mnfr. pickles and preserves," but it is unclear what happened after that. Her exact death date is also unknown. No known obituary was published. After the Great San Francisco Fire of 1907, reference to Abby and her cookbook all but disappeared until a copy surfaced in 1984 at a Sotheby's auction in New York City. The Schlesinger Library purchased it and at the time it was thought to be the first cookbook published in the United States by a Black woman, until Malinda Russell toppled Abby from her throne in 2000. Like Malinda and Anne, Abby used her cooking skills to make her own way in the world - supporting her family and showcasing her talents. Ghosts in the KitchenOf course, we know about these women because they left a written record. We know about Anne through her husband Solomon and his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave and the records of Eliza Jumel. We know about Malinda because of her cookbook and the autobiography she includes in it. And we know about Abby because of her cookbook and her existence in newspapers and city directories. But there were tens of thousands of women of color making their own way on the strength of their culinary skills, just like these women, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Ashbell McElveen called James Hemings the "ghost in America's kitchen," but he wasn't the only one. Enslaved women and men shaped American food profoundly. And women of color - enslaved, freed, and born free - left their mark as well. Because I know how history works, I am hopeful that more records and cookbooks of cooks of color - published or not - will continue to show up in the coming decades. And when they do, I know they'll help us better understand how our food got to be the way it is, and where it can go in the future. Further ReadingAnne Northup:

Malinda Russell:

Abby Fisher:

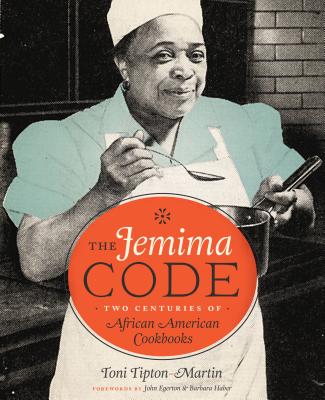

The Jemima CodeThe Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, Toni Tipton Martin. University of Texas Press, 2015. ISBN 0292745486. This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. If you want to know more about African American cookbooks, I recommend Toni Tipton Martin's The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. Although the information for each entry is sadly quite brief, it is nonetheless an important, enlightening, and beautifully produced catalog of all the known cookbooks authored by African Americans (real and fictional) in the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed