|

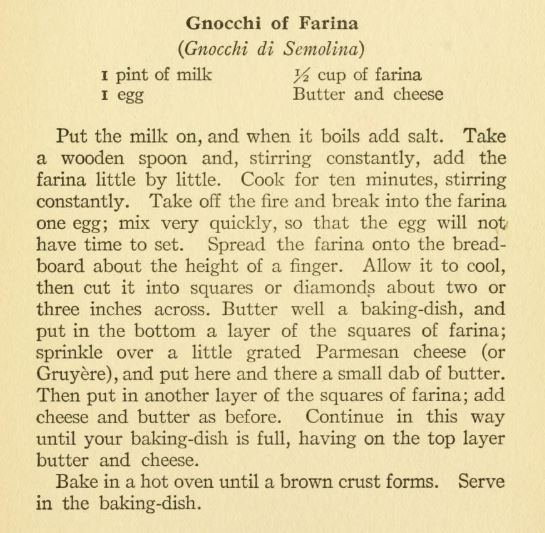

In these days of quarantine cookery, sometimes you run out of pasta. But no worries! If you happen to have semolina flour on hand (I use it for dusting pizza crusts - works like a charm), or even if you have some spare Cream of Wheat lying around, you can make these delightful gnocchi. They are also a good way to use up any milk that needs using as it uses 2 cups (a.k.a. a pint). Simple Italian Cookery was one of the first vintage cookbooks I ever cooked from, and it was this recipe. Published in 1912 by Antonia Isola, Simple Italian Cookery is considered one of the first Italian cookbooks published in America. Except, "Antonia Isola" was a pseudonym for Mabel Earl McGinnis, a New Yorker who had spent several years living in Rome before turning her hand to cookbook authoring. Simple Italian Cookery was her only known published cookbook and little else is known about her. Despite a fairly thorough search, I was able to turn up little more than references to her pseudonym. She apparently married a Norvell Richardson at some point, and a Mr. & Mrs. Norvell Richardson show up in 1956 in a Virginia newspaper, but simply in a list of guests. I did find this little reference in my newspaper searches as well. It's an interesting advertisement for the book, published February 24, 1912 in the New York Sun. McGinnis is touted as an "expert" and the reference to "Italian cookery is far from being all 'garlic and macaroni'" is an interesting a slightly racist reference to the cuisine of Italian Americans. By framing this book as "authentic" Italian, rather than the Americanized version of impoverished Italian immigrants, the publisher is setting Simple Italian Cookery in an interesting position - touting its social palatability by associating it with Europe and romantic Italy, trying to convince "American housekeeper" (i.e. white Anglo middle-class women) that the food is simple to prepare and affordable, and also distancing itself from connections to immigrant Italians, who were counted among the "undesirable" immigrants flooding New York (and other locales) in droves during the early 20th century. Gnocchi di SemolinaMabel's recipe is really a version of "Gnocchi alla Romana," made from semolina cooked on the stove top, cooled, and then baked again. They predate potato gnocchi, of course, and I vastly prefer them to the potato version. Plus, they're easier! The original recipe doesn't call for tomato sauce, although they are delicious that way. Parmesan cheese would be traditional, but any kind of aged cheese would work. The recipe above is fairly straightforward, especially if you use a pint canning jar to measure. Be forewarned, however, that two hungry adults can eat this whole pan by themselves (with seconds). A serving size is about 5 squares, and this recipe makes about 20 squares. So you may want to double it for more people, or if you aren't planning a salad or other side dish to accompany it. 1 pint of milk (2 cups) pinch of salt 1/2 cup farina/semolina flour/cream of wheat 1 egg butter cheese In a 2 quart saucepan over medium heat, bring the milk to a boil (watch it - it boils over easily!). Add the semolina gradually and whisk while you're at it. Keep whisking as it thickens up, otherwise it will bubble and spit hot semolina at you. You don't have to cook and stir constantly for ten minutes - but cook it for longer than you think, to get as much of the moisture absorbed as possible - the semolina should be quite thick. Pour out onto parchment paper, aluminum foil, or a wooden cutting board, pat into a rectangle a little more than an inch thick and let cool. Preheat the oven to 375 F. Once cool, cut into squares and layer in a buttered baking dish. Dot with butter and sprinkle with shredded cheese between layers (you'll get about 2 layers). Bake about 20 minutes, or until hot and bubbly. Serve hot with your favorite "gravy" or tomato sauce, or any other kind of sauce you like, or none at all. The gnocchi will be meltingly tender and delicious. Clearly I used a meat sauce with this, but you could easily make this a Meatless Monday dish - use plain marinara, vodka sauce, pesto, or go the cacio e pepe route and add pecorino (or parmesan) and plenty of black pepper. This takes a bit of preparation, but if you've been craving something hot and comforting but are out of pasta at home, gnocchi di semolina makes a great substitute. What comfort foods are you cooking while on stay at home orders? If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

6 Comments

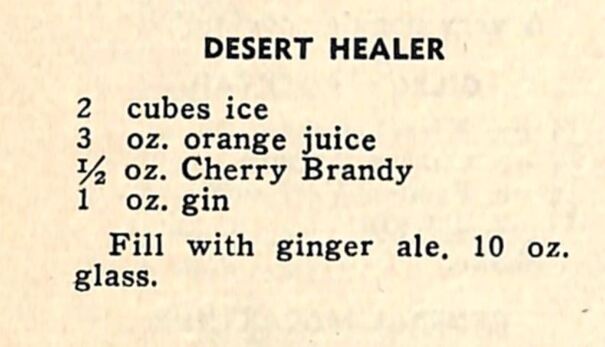

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, inspired by the cold, rainy weather we've been having lately, we "visited" the American Southwest with help from the Desert Healer cocktail from the 1946 Roving Bartender. We discussed Mexican food in America, including the cookbook California Mexican-Spanish Cook Book, published in 1914 by home economist Bertha Haffner-Ginger. We also talked about burritos, corn and nixtamalization (including hominy and tortillas), savory fruit salads, sauces, including celery sauce, macaroni and cheese, 19th century pickles, jicama, pickled herring, lutefisk and cod (small correction, mahi-mahi is dolphinfish, not tilapia), and we decided that next week's topics will be 19th century sauces and pickles!

Although cocktails called "Desert Healer" are all over the internet, I couldn't find any history behind either the name or the cocktail. I'm guessing it's just one of those cocktails that someone made up and it took off. If you like your cocktails on the sweeter side, but still with some complexity of flavor, you will probably love this one.

I found this recipe in the Roving Bartender (1946). I did get the recipe slightly wrong and only did a third of an ounce of cherry brandy, but more cherry brandy would have been even better! Desert Healer Cocktail (1946)

2 cubes ice

3 oz. orange juice 1/2 oz. cherry brandy 1 oz. gin (I used American gin, but any is fine) Place ingredients in a 10 oz. glass in order, then fill with ginger ale. Drink with a straw. I found this to be quite delightful and would definitely make it again, especially since it's such a nice way to use up the cherry bounce I made.

And, of course, given all of our discussion of celery and someone's idea that I make a cocktail with celery sauce (yuck), I thought that infusing gin with celery was a delightful idea, and it just so happened that I had cut up the remains of a head of celery for crudite to go with supper. So I had lots of delightfully fresh leaves and a few stalks leftover. Into a half pint jar they went with some gin poured over top and we'll let it steep until next week, when I'll have to decide what kind of gin cocktail I want to make with it.

As mentioned last week, the bar cabinet tour is still on the list, but I might do a recorded tour instead of a live one as I think it will be easier to manage. So stay tuned, and hope to see you all next week!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

In these days of stay at home orders, lots of folks are cooking at home more. And because we're supposed to grocery shop as infrequently as possible, lots of folks are also stocking up on food. So I thought this United States Department of Agriculture pamphlet (or possibly series of posters) from World War II on how to prevent food waste in storage and use would be fun and might include some bright ideas we can use again today. Published by the Home Economics Department of the USDA, these images are courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Join the ranks - Fight Food Waste in the home

Like during the First World War, preventing food waste in WWII was a way to help keep food supplies freed up for soldiers and the Allies. In addition, canned foods could be scarce from time to time, and so Americans were growing and home canning their own more than ever. In particular, meat and dairy products were precious and sometimes difficult to get, even with ration points. Preventing food waste not only helped secure the food supply, it also saved money. By the 1940s, the majority of Americans had access to electricity and therefore electric refrigeration. But while refrigerator companies wasted no time touting not only the benefits of electric refrigeration, but also how to use fridges, sometimes old habits died hard. Storing dairy products at room temperature, for example. Other old-fashioned wisdom like on how to store fresh vegetables, was sometimes lost. So home economists like those at the USDA took it upon themselves to make sure all Americans had access to correct food safety information. Milk and Eggs - Nature's Food clean, covered, cold... will stay good!

If you're wondering why "clean milk" will only keep a few days in the fridge, it's likely that the milk being referred to in the pamphlet was raw and unpasteurized. You'll notice in the photograph that the woman is placing a glass bottle of milk in the fridge, and quite near the freezer compartment. The rest of the refrigerator is full of glass refrigerator dishes - designed to keep food "clean, covered, and cold." The baby is present to remind parents of the importance of keeping even dessert dishes cold and unspoiled. Meat, Poultry, Fish are full of flavor, a cold dry place is what they favor. The meat dish in refrigerator is an ideal place.

Here again the same woman is putting raw meat in the "meat drawer" of the refrigerator - located directly below the freezer compartment. It appears to be a metal drawer that slides out completely, presumably for ease of cleaning. Most delightful for me are the photographs of the root cellar (center) and spring house (right). Of course, the earth keeps things at a constant 54 degrees F, and spring houses often were full of constantly running water, which not only kept the building cool, but some foods could also be placed in the water to keep them even colder. This was a common way to keep foods cool before electric refrigeration. Hung in the well or sunk in a running stream, the water would leach heat away from the foods and keep them cool. Cooked Meat, Poultry, and Fish

Cooling hot foods quickly before refrigeration is still recommended by health department professionals. Most botulism cases come not from poorly canned foods, but from foods left over overnight or for several days and being reheated and consumed. Save Every Drop of Oil or Fat

Of course during the war, waste fats were saved for munitions manufacturing. But here was have answered the age-old question as to whether or not you should store your bacon grease in a coffee can at room temperature like grandma used to - don't! I recommend a glass container (canning jars are nice) in the fridge or freezer. It lasts forever there, the glass container won't rust, and is easy to clean. Wilt Not, Waste Not.... Fresh Vegetables

I am extremely tempted now to store my celery not in the crisper drawer, but in a jar of water! Of course, finding a place for it to stand upright is difficult... However, you can store cut celery in water - it will become extremely crisp. Fresh corn, garden peas, and young fresh lima beans all convert sugars to starches quite quickly after being picked. Keeping them in their pods helps prevent them from drying out. Fresh Fruits Are Best In Season with care... they'll keep within reason.

If you've ever taken a container of raspberries from the fridge with dismay to see them growing mold, perhaps it would be best to follow this advice. Certainly don't wash berries until just before use. But my goodness - I wish I had the sort of fruit rack pictured above - pears are the hardest by far to keep from spoiling or ripening too quickly. A Cool Airy Place to Suit Hardy Vegetables and Fruit.

I like this wooden storage rack as well, apparently made from wooden fruit crates. Apples and citrus up top, a large cabbage and perhaps onions (with covering) on the second rack, and potatoes, covered to keep from sprouting and turning green, on the bottom. One lament of mine is that modern kitchens almost NEVER have good storage for vegetables like this. To Keep bread, Cake, and Cookies Nice, protect from insects, mold, and mice.

Do you have a bread box? My mother-in-law does, and my parents' house has a built-in bread drawer in the kitchen - made of metal. I do not have a bread box, largely because we keep things in plastic these days and thus don't need the close quarters of the wooden or metal box to keep bread wrapped in paper from drying out. But definitely in July and August I keep my favorite cracked wheat sliced bread in the fridge, otherwise it does mold quite quickly. Sugar - Flour - Cereal - Spice

I am proudest, perhaps, of my baking cupboard, in which almost everything is stored in lovely, air tight glass jars. The brown sugar is never hard, the flour stays fresh, and the dried fruit don't get TOO dry. Storing things in air-tight containers also prevents an infestation of Indian meal moths, which I had the misfortune of dealing with precisely once before I started storing everything in glass. I think they came in with a batch of bulk peanuts in the shell. Of course, they get their name from "Indian meal" - a.k.a cornmeal. They also keep out mice and other insects, although thankfully I have never experienced weevils. The few home-canned foods I have on hand (and homemade booze), I keep in cupboards so they stay in the dark. I have heard of the mysterious and delightful-sounding kitchen accoutrement called a "fruit room" - a cool, dry, dark place perfect for storing not only fresh fruit but canned goods. My dream home has one, along with a butler's pantry. How do you store foods in your home? Do you have a fancy pantry? Or do you make do with kitchen cupboards and a metal rack, like I do? If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, with some trepidation, I entered into the territory of raw egg and alcohol with the Cherry Brandy Flip - made with some of my homemade cherry bounce!

Plus, we talked about bananas and banana bread, tonic water, Midwestern food, beer, and more! Special discussion of candle salad. Proceed at your own risk.

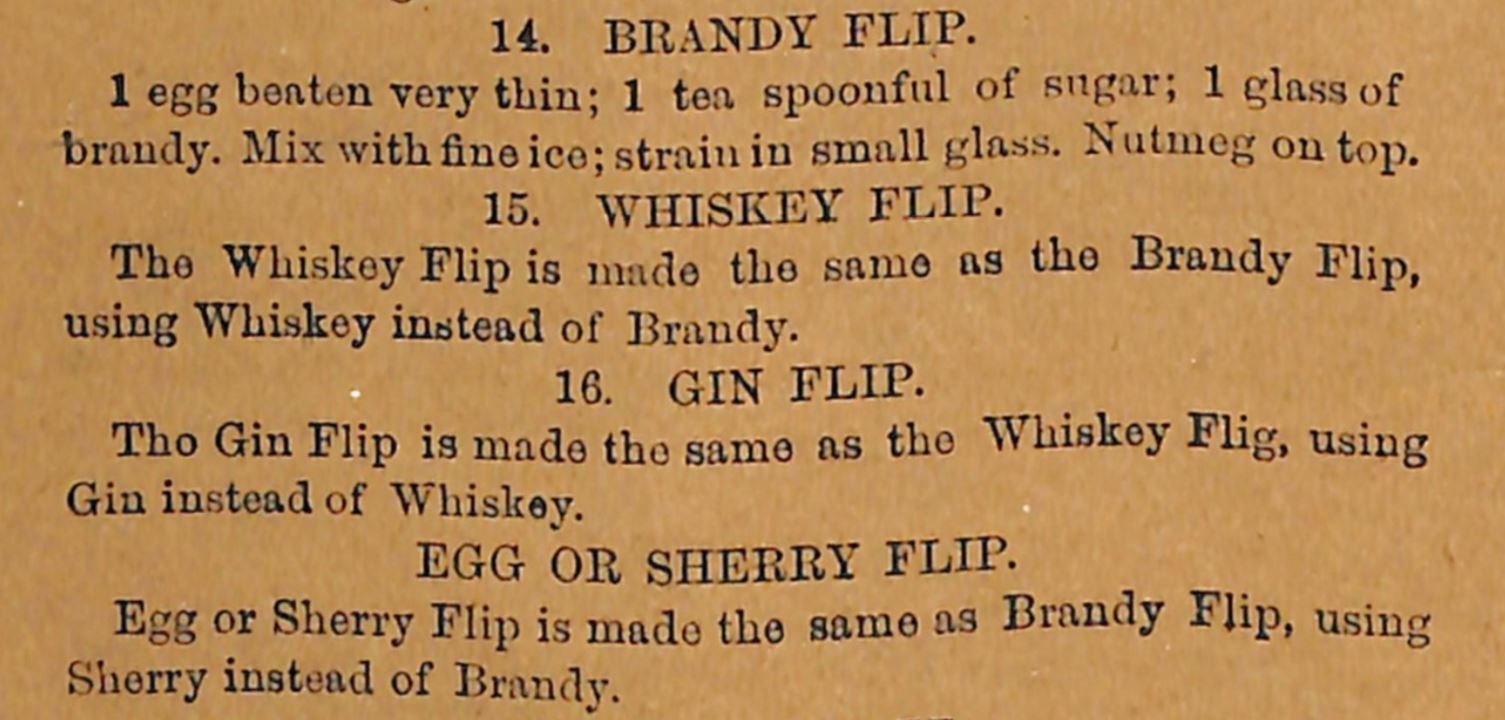

Brandy flips are quite old, and I found a reference to them in The American Bartender, or, the Art and Mystery of Mixing Drinks (1874). There are several flip recipes in there, actually. But I went with the brandy one because I wanted to use up some of my cherry bounce (which is really a cherry brandy), and also because it was requested by Food Historian fans.

The term "flip" is quite an old one, and originally referred to a mixture of ale, sugar, and spices heated with a hot iron poker, which cause the drink to froth or "flip." Later, eggs were added, and eventually, the cocktail shaker was exchanged for the hot poker. The first printed recipe was published in Jerry Thomas's 1862 Bar-Tender's Guide. Known as the father of American mixology, Thomas listed a number of variations on the flip, including the "Cold Brandy Flip." Flips are similar to eggnog, but not quite the same as they do not contain cream, as eggnog does. But the flavor profile is similar. Flips have fallen out of fashion in most bars, in large part because they require the use of a raw egg. Historically, eggs were not washed before being sold, and the protective coating on the shell protected them from contamination, including salmonella. Today, eggs are washed before being sold, removing the protective coating, and opening them up to the possibility of salmonella contamination. Some people claim that the alcohol "cooks" the egg, and hot water (or hot poker) in the hot flips certainly does. But please keep in mind that you proceed at your own risk if you choose to replicate this cocktail. I thoroughly washed my egg again, just to be sure, and used a pastured, free-range, local egg. But you never know. Cherry Brandy Flip

1 whole egg

1 jigger (1 1/2 oz.) cherry brandy 1 oz. simple syrup cracked ice freshly grated nutmeg Place the egg, brandy, and simple syrup in a cocktail shaker WITHOUT ice (this is called a dry shake). Make sure to seal the shaker well. Shake thoroughly until your arms are tired. This emulsifies the egg. Add cracked ice, and shake again, until your arms are tired. Strain into a small wine glass or generous cocktail glass, and grate fresh nutmeg on top. This was better than I expected, although it does taste a bit "eggy" - probably those lovely free range eggs I used. If I made it again, I would add the nutmeg before shaking, or stirring it in. The egg not only emulsifies into something fairly creamy, it makes a frothy head as well. As for the Food Historian Happy Hour Livestream, we MIGHT be doing a tour of my vintage bar/liquor cabinet next week AND, I got a new, higher quality camera for livestreaming. So you can look forward to way less pixelation. Hope to see you next week!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. I had a blast and everyone asked such great questions!

In this week's episode, we covered a LOT of ground and discussed how applejack is made, shrub, eugenics, Americanization of immigrants, comparisons between modern issues with dairy farming, dumping milk, and plowing under fields of vegetables and what happened during WWI and the Great Depression, types of dairy cows and how dairy farming works (including a discussion of veal), Victory gardens, agricultural policy history, historic baking, and flips (including Tom & Jerry). WHEW! The hour flew by and I had so much fun. You can watch the whole thing below.

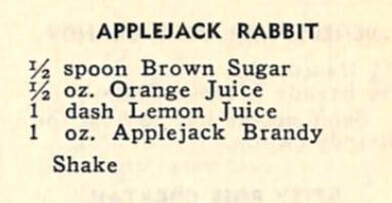

And of course, I made a vintage cocktail! This week's cocktail is the Applejack Rabbit and it comes from the 1946 cocktail book, The Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly.

We talked a little bit about cocktail glasses and serving sizes because of course this week I did NOT use a Collin's glass, but rather a small martini glass. In his introduction to The Rover Bartender, Kelly writes, "As the drinks are shorter now, the glasses for mixed drinks should be shorter and the drink recipes in this book are especially for cocktail glasses of not over 2 1/2 ozs. If a larger glass is used, the proportions will have to rise. You may serve a pony of cognac in a 20 oz. snifter glass, but if a cocktail glass is not near full it is unsatisfactory to the customer." I can certainly agree! But as someone who prefers a cocktail to be only a few ounces, I can't say I enjoy the generally much larger glasses of modern bars and restaurants. They may be easier to handle and clean, but they're too big! Applejack Rabbit Cocktail (1946)

The original recipe is as follows:

1/2 spoon brown sugar (I used about half a tablespoon) 1/2 oz. orange juice 1 dash lemon juice 1 oz. applejack brandy Pour over ice in a cocktail shaker and shake for longer than you think you should to make sure the brown sugar is dissolved. Strain into a small cocktail glass, such as martini glass or old-fashioned champagne glass. Sip cold. Virginia Apple Cake Recipe

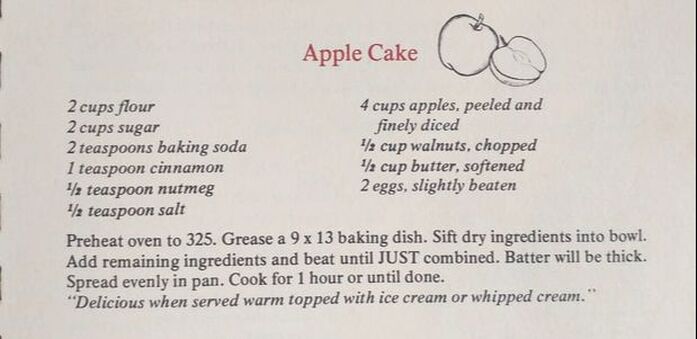

And, since we talked about historic baking, I thought I would share the recipe for apple cake I found recently in my copy of Virginia Hospitality (1976, my copy is the 1984 reprint). This particular Junior League cookbook is quite good with many of the recipes arranged by region and with decent head notes for many. Alas, this "Apple Cake" has neither headnotes nor region assigned. But it looked intriguingly easy and used up quite a bit of apples.

However, as I discussed in the episode, it really is a strange cake. As such, while I've included a photo of the original recipe, I've written my own version to help walk you through how the recipe should work.

2 cups flour

2 cups sugar 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg 1/2 teaspoon salt (note - I would add 1 teaspoon next time, the cake tasted a bit "flat") 4 cups apples, peeled and finely diced (about 3 medium apples) 1/2 cup walnuts, chopped 1/2 cup (1 stick) butter, softened 2 eggs slightly beaten Preheat oven to 325 F. Grease a 9"x13" baking dish (I used metal). Whisk dry ingredients in a bowl, then add apples and walnuts and stir to coat. If butter is refrigerated, microwave in 10-15 second intervals until very soft but not totally melted. Add butter and eggs to the dry ingredients and mix/fold with a wooden spoon until no loose flour remains. It will seem like not enough moisture - just keep folding, it will come together. The batter will be very thick. Do not overbeat. Spread evenly in the pan. Bake for 1 hour or until done. (I baked mine for 1 hour and 5 minutes, as the middle still seemed a bit soft). In all, my husband LOVED this recipe, but it was not my favorite. Next time I would definitely add some extra salt as the cake tasted a bit "flat" without it. In retrospect, I also MIGHT have accidentally added 2 teaspoons of cinnamon instead of one? Oops. It was too much cinnamon for me, but as I said, my husband loved it as it reminded him of carrot cake. Baking it for an hour at 325 seemed like way too long, but it did result in nicely caramelized edges (all that sugar). However, all the apples melted into the cake! So next time I would probably cut them a bit bigger. I did almost mince them in some cases.

So what did you guys think of this week's episode? Are you going to join me next Friday on Facebook? I hope to see you there! Thanks again to everyone who watched live and remember, if you have any burning food history questions, you can send them to me in advance, message The Food Historian on Facebook, or ask live during the broadcast. See you soon!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

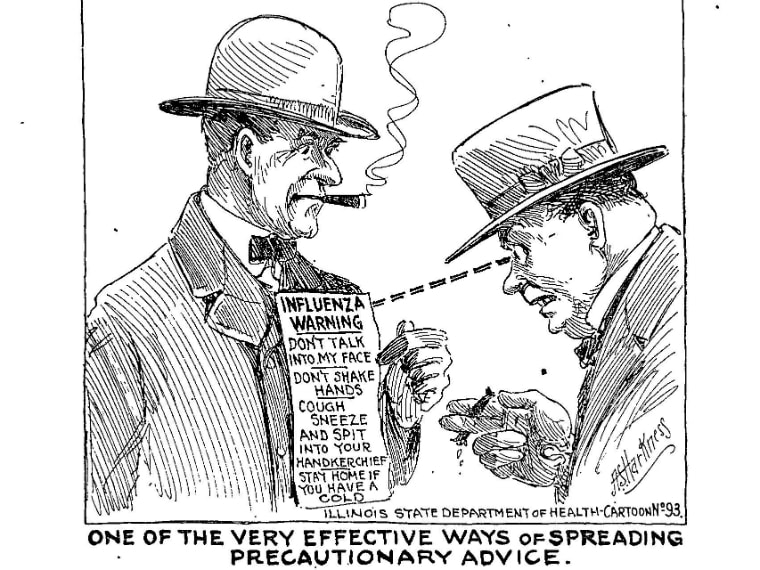

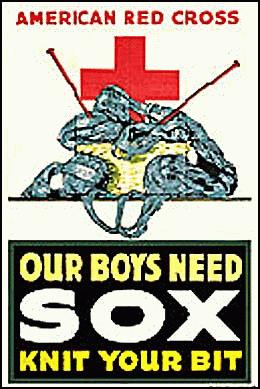

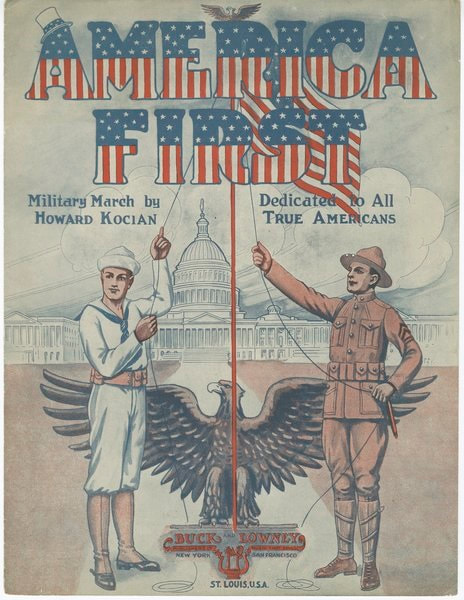

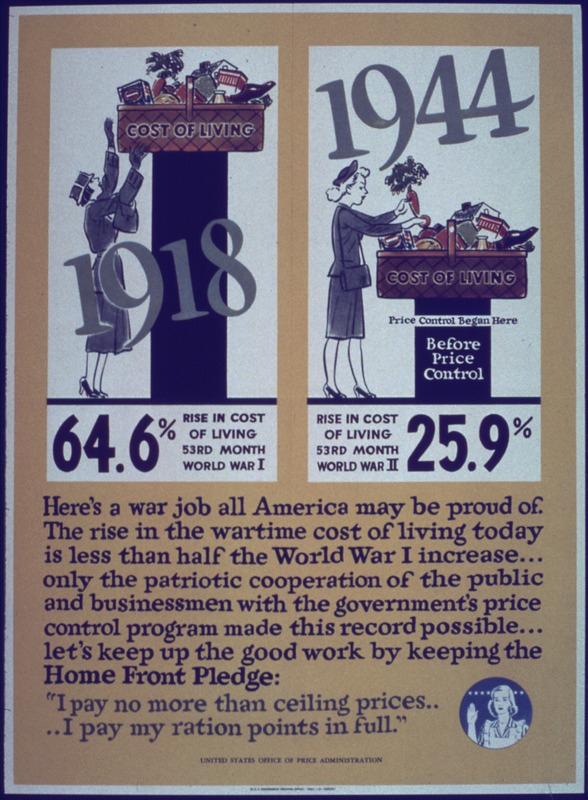

Y'know that old saw, "Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it?" Well, like a lot of old adages, this one has a big grain of truth in it. Historians often can see parallels to the modern world as they study history. Indeed, my area of specialty - the Progressive Era and World War I home front - has led to LOTS of comparisons to modern life. But with the addition of the coronavirus lockdown, the comparisons grew more numerous. To that end, I thought I would catalog some of the striking similarities. Failure of Bureaucracy: Military SupplyOne thing that has becomes especially striking at this time is the failure of the federal government to manage national supplies during an emergency. In this instance, it's the management of medical supplies for COVID-19, particularly personal protective equipment (a.k.a. PPE). States are competing on an open market and with each other, driving up prices and leading to shortages. To make up the shortfall, ordinary citizens are creating homemade versions of masks, face shields, and other equipment. During the first months of the U.S. entrance into World War I, the exact same thing was happening. Historian Robert Ziegler in his book America's Great War: World War I and the American Experience, outlines the deplorable state of military supply following the Spanish American War. Individual battalions were competing with each other on the open market to purchase supplies, thus driving prices up. In addition, the United States had never fielded such an enormous army and the production of other military supplies, such as uniforms and rifles had yet to keep up with the demand of a suddenly-enormous army. According to historian David M. Kennedy, in his book Over Here: The First World War and American Society, soldiers were sent to Europe with hardly any training. Men and boys who had been recruited in July, 1918 were on the front lines by September. Some men arrived never having used a rifle, and had to take an intensive 10 day course before being sent into battle. The logistics of shipping war materiel, both within the borders of the United States and overseas was also a mess, causing railroad and port backups. Some credit the poor supply of soldiers in training camps (inadequate clothing, bedding, housing) with exacerbating the effects of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Combined with this was the efforts of the American Red Cross. Famed for providing bandages and nursing aid during the American Civil War, thousands of chapters sprang up across the nation and throughout 1917, women were encouraged to "knit their bit" by knitting sweaters, socks, wristers, and watch caps for "our boys" being sent overseas. Why? Likely because military supply chains were, as stated, in shambles and because it was easier (and cheaper) to task the nation's women with keeping soldiers warm than to mobilize factories. Wool socks in particular were in high demand because of the poor conditions in the trenches. But by 1918, according to historian Christopher Cappazola in his book, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, the federal government was frantically telling women to STOP knitting, likely because military supply was completely reorganized. Although there are plenty of resources about knitting in WWI and the American Red Cross (including this lovely one), few people seem to have made the connection between "knitting your bit" and the failure of military supply. It was only part-way through American participation in the war that the federal government reorganized military supply under a centralized Quartermaster General. It wasn't until the Korean War that the United States passed the Defense Production Act (1950), which empowered the federal government to compel private business to prioritize the production of war materiel and prevent hoarding and price gouging. If the United States were to learn the lesson of WWI supply today - the federal government would coordinate with individual states to purchase - and allocate - medical supplies where most needed, instead of bidding against states on the open market. Xenophobia, Immigration, RaceIn the years leading up to the First World War, the United States was inundated with immigrants from all over the world, but particularly Eastern and Southern Europe. The United States was also recovering from the abandonment of Reconstruction and Black Americans were becoming more and more prosperous, with a growing middle class. Combined with a brain and labor drain on rural areas, this led to people like President Theodore Roosevelt warning of "race suicide" for White Anglo Americans unable to keep pace with the more fertile immigrants. Roosevelt also worried about rural life and started the Country Life Commission to study and combat the drain of population from rural America to urban areas. Tempted by "cosmopolitan" life, reformers worried, young people would be corrupted and the bedrock foundation of democracy - the landowning yeoman farmer - would diminish. Unfortunately for reformers, the majority of people in rural areas lived difficult lives and particularly in the South, most did not own the land they farmed. But the idea that rural America, and farmers in particular, are the "salt of the earth" is an idea that has persisted even today. With "flyover country" being courted by politicians, especially conservative ones, with every election. Immigration and race remain hallmark dogwhistles in modern politics. The Trump campaign used the slogan "America First" on the campaign trail - echoing the campaign slogan of Woodrow Wilson leading up to his first term as a neutral isolationist. It was a policy he would abandon in his second term, as the U.S. entered World War I in the spring of 1917. Americans were notoriously isolationist in the early 20th century (except for their colonialist ambitions in Central America, Hawaii, and the Phillipines) and America's first propaganda machine had to be created to convince them that joining the war was a good idea. To convince them, Woodrow Wilson invented the idea of defending and spreading democracy (and American exceptionalism) abroad - a policy that has continued to be used in every American war since then. Attempts to Americanize immigrants remained in effect throughout the war. Progressive reformers from settlement houses and canning kitchens on up to proponents for the war which thought a draft would help Americanize immigrants tried to force people into the mold of White Anglo American (usually Northeastern) culture. Black Americans faced similar pressures, and segregated versions of just about every middle-class voluntary organization - including the Red Cross - was implemented during the war. Following the war, newly economically mobile Black Americans, buoyed by industrial jobs for war production, faced even more hostility than before. Resentment by racists clashed with confident (and armed) veterans returning from war. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is just one example of Black WWI veterans attempting to defend themselves and their communities. Race riots, lynchings, and a dramatic expansion of the Ku Klux Klan were the hallmarks of 1919, 1920, and beyond. Today, Black American communities still deal with over-policing, incarceration, and violence. Latinx-Americans have dealt with a dramatic ramp-up of incarceration, family separation, and deportation (even of children), as well as more casual racism. And Asian-Americans in particular have borne the brunt of some horrific incidents of racism directly related to the coronavirus - as the ignorant believe that they (regardless of whether or not they had been to China recently, or were even of Chinese descent) were "carriers" of the disease - another old saw of racism most famously used by Nazis against the Jews (among others). The High Cost of LivingIn the two decades leading up to WWI, the United States underwent a series of depressions and recessions. Starting with the Depression of 1893 (which the US did not recover from until 1897-98), and with smaller recessions in 1907 and 1913-14, the "high cost of living" (commonly abbreviated as "HCL" or "H.C.L.") saw a dramatic rise in cost of living, including food and housing, while wages stagnated. Called "stagflation" by economists, this situation led to labor unrest, and strikes, food boycotts, and food riots were all common during this time period. Socialists were also in political ascendancy due to income and labor inequalities. Labor strikes were often broken by deadly force. Food boycotts and riots remained the purview of the desperate - often women with starving children which tugged at the heartstrings of wealthy and middle-class White Progressives, even as some were organized by socialist activists (read about the 1917 food riots in New York City). Many of the strikes and riots of the 1900s and 1910s led to serious labor reform, including the ending of child labor, worker safety reforms, reduced hours, and more. New York City during WWI tried to pass a minimum wage law, but it was vetoed by the Mayor. Today's parallels include a different sort of high cost of living - most "luxury" items are cheaper than they've ever been, but housing, education, healthcare, and food costs have risen by as much as 200% in the last 20 years. In addition, democratic socialists and real, "bread and roses" socialists have seen their numbers spike in the last few years. Activists are fighting for a minimum wage increase, universal healthcare, and other reforms, although union membership has taken a steep dive in the last few decades. Coronavirus has only highlighted the "essential" role many low-wage workers play in American life, and some retail workers, cleaners/janitors, and restaurant workers are now being hailed as heroes alongside medical professionals and scientists. War Gardens & RationingOne particularly fascinating trend that appears to be occurring right now is the skyrocketing sale of vegetable seeds and plants. Tied in part to the fact that so many Americans are sheltering in place and have time to garden, the resurgent interest in "Victory Gardens" is also a reaction to temporary shortages in grocery stores (due to logistics, rather than supply) and fears that the food supply might be endangered by coronavirus. The First World War was also one of the first times in American history that a concerted effort to get ordinary people to plant kitchen gardens. Of course, part of that was because of the changing demographics of population. People in rural areas had almost always had kitchen gardens. But as more and more people moved into urban and suburban environments, and fresh food supplies became easier and cheaper to acquire, kitchen gardens became less necessary, and most people who could afford to focused on flower gardens instead. But the U.S. entrance into the war, with its commitment to feeding the Allies, came with very real fears that food would be in short supply. This was reinforced by rhetoric from Wilson and Herbert Hoover, the new U.S. Food Administrator, who knew that in the spring of 1917, existing crops would be inadequate to feed both Americans, their growing army, and the Allies without serious changes. Enter war gardens and voluntary rationing. Hoover was the brains behind the idea of voluntary rationing - he wanted Americans to show the world their personal fortitude and strength through voluntary efforts, including rationing. He also believed that the bureaucracy necessary to enforce mandatory rationing would not only be hugely expensive, it would also be ineffective. To lead by example, Hoover and the entire Food Administration were all volunteers. Rationing included refraining from eating wheat, meat, butter, and sugar whenever possible, and by the fall of 1917, "wheatless, meatless, and sweetless" days were implemented. Grain and flour substitutions, sugar substitutions, and vegetarian meals became more normalized during the war. The National War Garden Commission was also a voluntary organization, albeit a private, not public, one. Started by forestry magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, it encouraged Americans, especially school children, to plant "war gardens" (later renamed "victory gardens," a name that would resurface during WWII) which would provide fresh vegetables for ordinary people. Not only would this free up conventional food supplies, the production of local food would also free up transportation resources, which by the end of 1917 were becoming so congested that the United States temporarily nationalized its railroads. Spanish Influenza "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. And, of course, the obvious one. I've already written a bit about the Spanish Flu, but it bears noting that during the course of the 1918 pandemic, the government was reluctant to report real numbers or spread information about the severity of the pandemic because they were worried that it would endanger the war effort or reduce morale. Some cities, like Philadelphia, held enormous and patriotic Liberty Loan parades, allowing the virus to spread like wildfire. In fact, despite evidence that the influenza strain likely started in the United States, it wasn't until neutral Spain was infected, and its newspapers reported the real death toll, that the general public learned of the pandemic. Hence the name, "Spanish Influenza." Similar things are happening now, with the Trump Administration's initial reluctance to admit coronavirus was a serious problem because they feared the effect on the economy. Conflicting information in the media (and from the President) about the severity of the virus and the need for social distancing and stay at home orders have exacerbated the problem here in the U.S. More recently, a dearth of testing has led to some experts to conclude that the death toll is severely underreported. We are now also learning that China has likely suppressed or underreported the true infection rate and death toll from coronavirus. Thankfully, unlike 1918, when newspapers largely cooperated with government propaganda efforts (under threat of having their licenses revoked, effectively putting them out of business), modern information is more accessible and immediate than ever through the internet. Although sifting fact from fiction is a bit more difficult these days. ConclusionThere are a number of other Progressive Era similarities to modern life - women's rights, environmental conservation, voting rights, and income inequality, to name a few - that I chose not to include in this list largely because they were less immediately relevant to the coronavirus pandemic. To learn more about food in World War I, check out my Bibliography page, which was links to lots of great books. I hope you enjoyed this read. It certainly helped me organize my thoughts around these similarities and I hope that we can learn from the successes and failures of the past. That's all any historian can hope. Thanks for reading. Stay safe, stay home. If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Like many of you, I'm 100% at home right now. Working from home, writing from home, eating at home, and generally not leaving the house except for a weekly grocery run! To alleviate boredom, sometimes it's fun to listen to podcasts while doing things like laundry, working out, the dishes, or any other task that occupies your hands but not your brain. There are a number of newer food history podcasts out there, so I wanted to share some just in case you weren't familiar. 1. A Taste of the Past Linda Pelacchio has been hosting "A Taste of the Past" over at Heritage Radio Network since 2009. She interviews chefs, food writers, and food historians. And with over 300 episodes to choose from, she'll keep you entertained for a long time. 2. Gastropod Gastropod is another of the more established food history podcasts out there, and hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twiley have great rapport as they look at some of the fun (and usually relevant) food histories out there. New episodes every two weeks. 3. The Feast The Feast is hosted by medievalist and academic food historian Laura Carlson. Started in 2016, there's lots to love here, so dig in! 4. The Fantastic History of Food Hosted by cookbook author Nick Charley Key, this brand new podcast (started in 2019) already looks like a fun one. 5. Victory Kitchen Podcast My new Instagram friend, author Sarah Creviston Lee (another Sarah!) has started a Victory Kitchen Podcast, which is quite good. In it, she focuses on food and rationing during World War II. Only five episodes so far, but all fascinating and her supplemental blog posts are excellent. 6. Florida Oranges: A Colorful History Erin Thursby, author of the book, "Florida Oranges: A Colorful History," has a podcast based on her book! Launched last year it's a deep dive into the history of Florida's orange growing industry. Not as polished as some of the other podcasts, but still worth a listen. What do you think? Did I miss any? And of course, if you get really bored, you can listen to old episodes of History Bites. I promise as soon as the book is done, I'll get back to podcasting! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

The second episode of Food History Happy Hour is now concluded and it was just as fun as the first! This time went both more and less smoothly - less so because I was having technical difficulties with Facebook Live and had to switch to an older version, so that was a bit stressful. More smoothly because lovely friends and Patreon patrons asked some great questions after the first one, so I had some planned topics to discuss. We talked about the cranberry scare of 1959, the origin of the term "comfort food," and the variations on weights and measurements in cooking and baking, as well as forays into the origins of soup, chili, and some discussion of the Spanish Flu pandemic and why I study food history in the First World War.

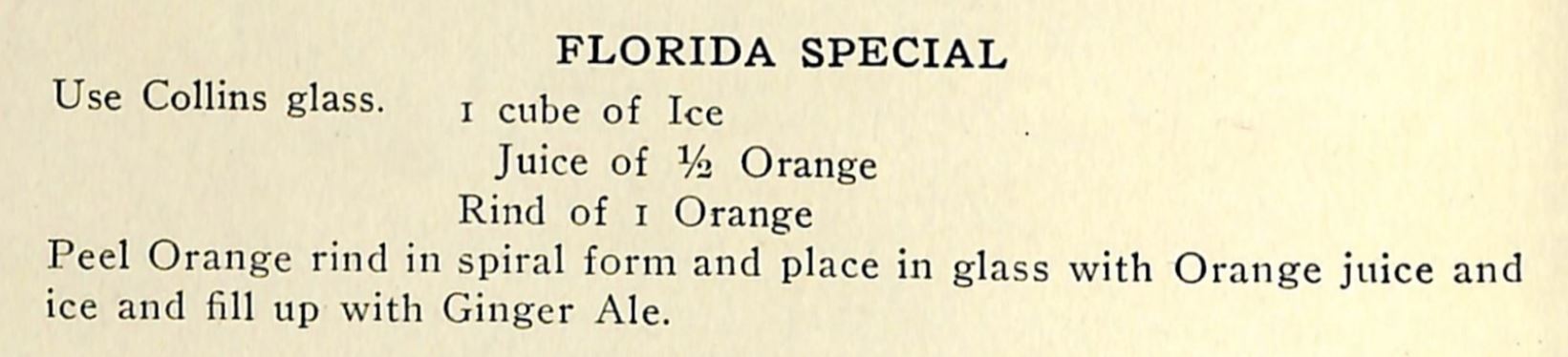

This week I made a non-alcoholic beverage (to the consternation of some viewers) called the "Florida Special." Although one Facebook fan told me not to make it (conflating it, I think, with "Florida Man"), it sounded too delicious to resist.

The recipe comes from "Recipes for Mixed Drinks" by Hugo R. Ensslin, published in 1917. I did tweak it a bit, as you'll see from the recipe below.

Florida Special

2 cubes of ice in a Collins (a.k.a. highball) glass [one just didn't seem enough] rind of 1 orange juice of 1 orange 2-3 dashes orange bitters (optional) ginger ale Using a sharp knife, a supreme knife if you have one, cut the rind from the orange in a single piece and place in the glass. Cut the peeled orange in half and with a citrus press or reamer (or just with your hands), squeeze juice into the glass (if using hands or reamer, be sure to catch any seeds, if there are any). I used my 1940s Juice O'Matic, which I love. Add a few dashes of orange bitters (optional) and fill with ginger ale. Stir well with a straw and enjoy! I found this to be quite delightful, although if you wanted to cut back on the sugar (my orange was quite sweet), it would probably be equally delightful with plain or orange flavored seltzer. I would not recommend substituting bottled orange juice for the fresh, however. It would probably still taste good, but would be a completely different drink. Thanks again to everyone who watched live and I hope to see you all next Friday! Remember, if you have any burning food history questions, you can send them to me in advance, message The Food Historian on Facebook, or ask live during the broadcast. See you soon!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

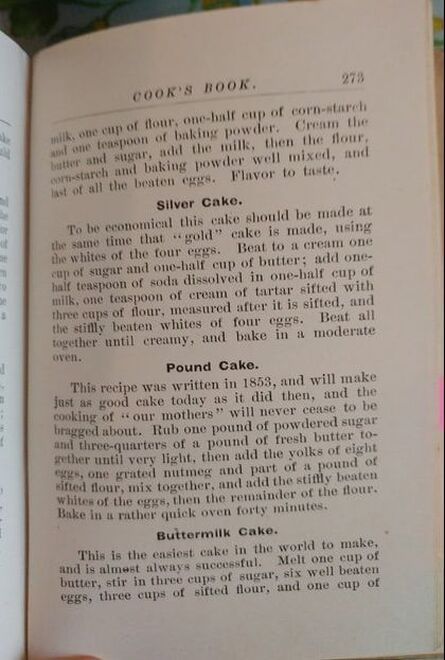

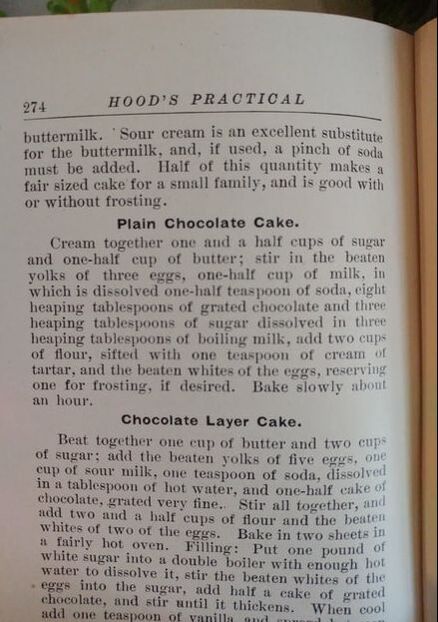

I haven't felt like cooking or baking much lately, except, of course, until I do. I wanted to bake an easy from-scratch cake and thought I would peruse my vast cookbook collection to see what I could find. Published in 1897 in Lowell, Massachusetts, Hood's Practical Cook's Book: For the Average Household, is delightful. My particular copy is in near-mint condition in part because it was printed on high quality paper. It's also quite small, almost pocket-sized. Buttermilk Cake This is the easiest cake in the world to make and is almost always successful. Melt one cup of butter, stir in three cups of sugar, six well beaten eggs, three cups of sifted flour, and one cup of buttermilk. Sour cream is an excellent substitute for the buttermilk, and, if used, a pinch of soda must be added. Half of this quantity makes a fair sized cake for a small family, and is good with or without frosting. What a delightful little description! And indeed, it IS the "easiest cake in the world to make," in part because it uses melted butter. In modern kitchens, where butter is almost always kept in the fridge, softening it for a typical cake recipe takes forever. BUT - I did make a few teensy tweaks, and of course the original recipe as written doesn't include any instructions for the oven temp, baking time, or type of cake pan to use. So, I figured I'd give my own version, especially since, in a household of two adults, I think we qualify as a "small family," so I cut the recipe in half, as suggested. I also added a "pinch" of soda as I wasn't sure the eggs alone were enough to leaven the cake. And despite the fact that it probably would be great without frosting, I felt like frosting, and blackberry jam seemed like the perfect fit for a simple buttermilk cake. 1897 Buttermilk Cake with Blackberry ButtercreamFor the cake: 1/2 cup butter (1 stick), melted 1 1/2 cups granulated sugar 3 eggs 1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour pinch of salt 1/4 teaspoon baking soda 1/2 cup buttermilk For the frosting: 3 tablespoons butter, softened 1/4 cup blackberry jam powdered sugar Preheat the oven to 350 F. Grease an 8"x8" metal baking pan. Stir sugar into melted butter and add beaten eggs, flour, salt, baking soda, and buttermilk. The batter will be quite thick. Pour into baking pan and level with a spoon or spatula. Bake for approximately 45 minutes (check after 30), or until the cake center is firm and springs back when gently depressed. While the cake is baking, make the frosting. Beat the jam and butter together, then add powdered sugar, 1/4 cup at a time, until the frosting thickens. When the cake is done, remove from pan and cool on a baking rack. Once cool, frost the top. This is a rustic-looking cake and mine got quite a dome, but if you CAN slice it in half, feel free to do so and fill with frosting (double the recipe).  I couldn't wait for my cake to cool completely before frosting, so the frosting got a bit melty, but it was still delicious! The cake wasn't too sweet, despite all the sugar in it, and closely resembled the taste and texture of Lazy Daisy/Hot Milk Cake, but somehow even lazier? Delightful. I will definitely be making this again, but I might experiment with one fewer egg (or two extra large eggs), as the cake did taste a bit eggy and obviously rose quite high. I'm guessing it's because eggs in the late 19th century weren't quite as large as today's standard large eggs. So what is everyone else baking during home confinement? Anything interesting? Share in the comments! As always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

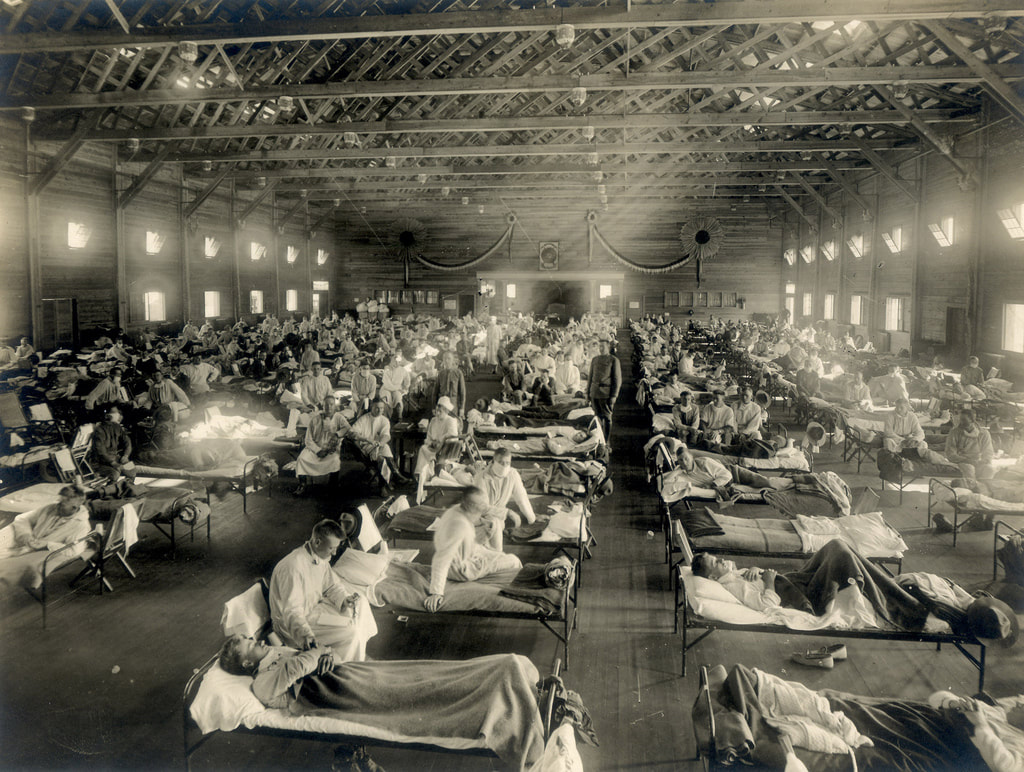

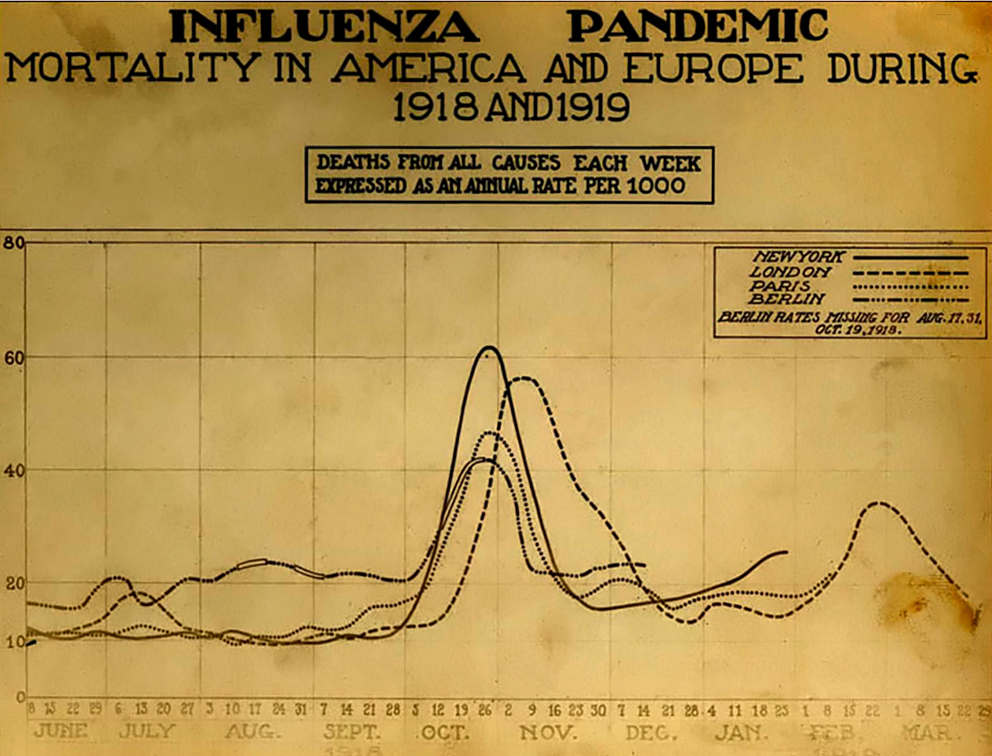

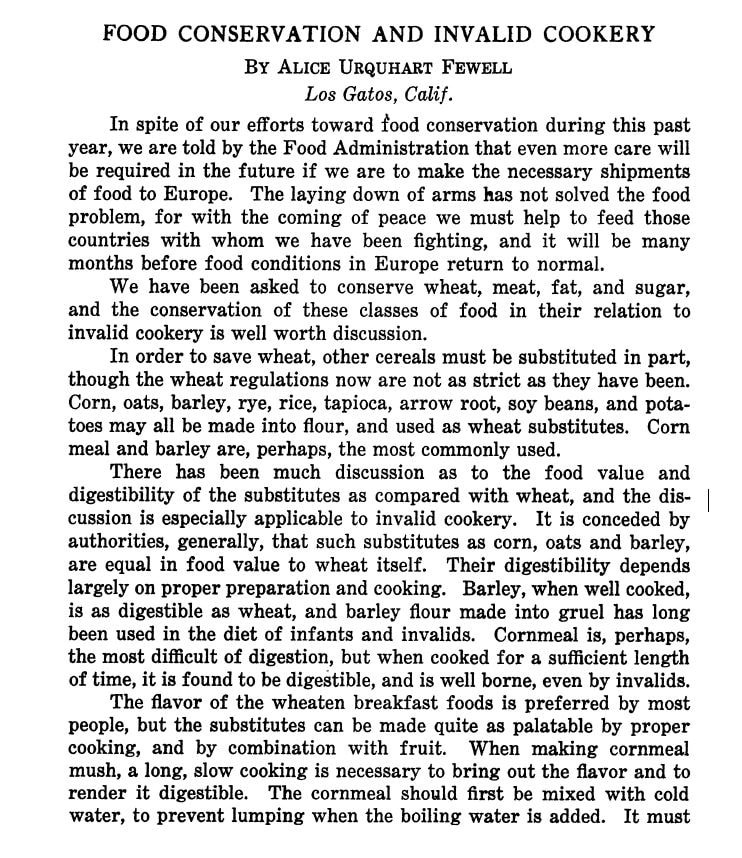

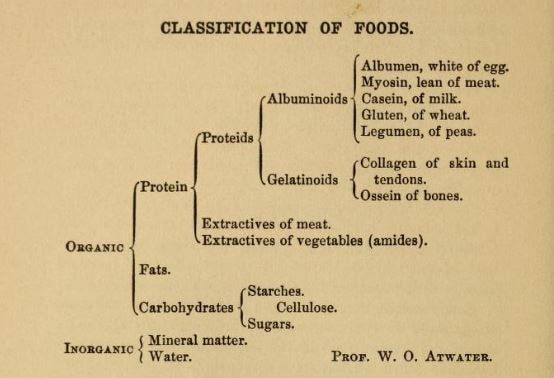

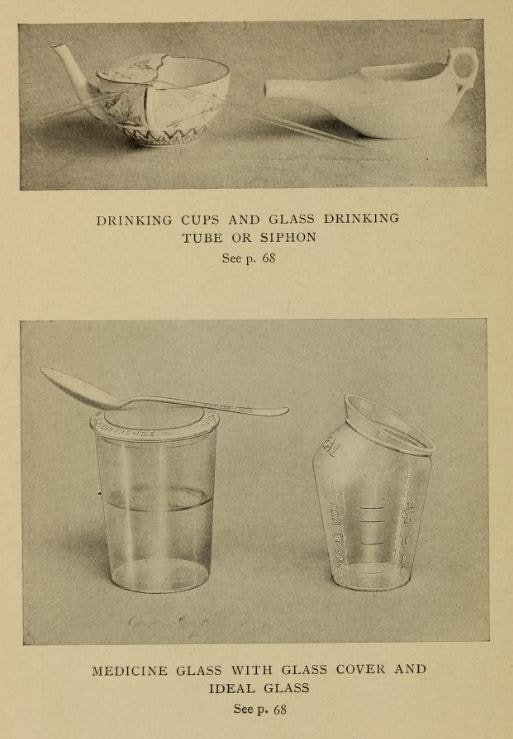

Given the prevalence of COVID-19 around the world, the comparisons to the influenza epidemic of 1918, and a reduction in my hours at work, I finally spent some time today familiarizing myself with the "flu." Folks, it wasn't pretty. The origins of what became known as Spanish Influenza is disputed, mostly because influenza mutates frequently, especially when humans are housed in close contact with animals. Some researchers claim British army camps in France, some claim Austria, some China, many as early as 1917. But one instance is believed to have occurred in Haskell County, Kansas, in January, 1918 (Barry, 110-112). It was a strange new version of the well-known influenza - violent coughing, nosebleeds, pneumonia, and in some cases, skin that turned so dark blue it was difficult to tell if a person was Black or White. And most concerning of all, the disease seemed to strike young, healthy people more than the typical infants or elderly. The influenza ran through crowded conditions during the very cold winter and spring in Army camps in Kansas, including Camp Funston, and then seemed to disappear. But it was spreading across the globe. In May, 1918, it reached Spain and sickened Alfonso XIII, the King of Spain. Unlike the United States and other European nations, Spain was politically neutral. And unlike its neighbors, who refused to reveal any sense of weakness that news of an epidemic might bring, Spain reported about this new strain of influenza in its newspapers. Hence the name, "Spanish flu." By August, 1918, a more virulent strain appeared in France, Sierra Leone, and Boston. By October the disease had become a global pandemic. The vast majority of those who died were under the age of 65. One theory as to why older people, who are typically first victims, would have been spared is that they may have developed immunity as young adults due to exposure to the "Russian flu," an influenza pandemic from 1889-1890. In addition, modern research has determined that the Spanish flu caused a violent immuno-response. The stronger the immune system, the more violent the response. Other factors in the high mortality rate may have included aspirin poisoning, as many of the worst death rates in the United States coincided with the US Surgeon General's recommendation that mega-doses of aspirin be used to treat the symptoms of influenza. Few public records of influenza remain, in large part because few were ever created. Like his counterparts in Europe, President Woodrow Wilson feared negative press and its impact on national morale. By the fall of 1918, he was determined to hammer home victory by sheer force. By that time, the American press, influenced by George Creel's Committee for Public Information and the threat of censorship law, published nothing Wilson wouldn't like. So few references to the influenza epidemic exist in newspaper references, it is almost as if it didn't happen. But happen it did. The public denial of a problem extended to government assistance as well. State and municipal governments were largely left to fend for themselves. The only real advice came from the Surgeon General: "Surgeon General’s Advice to Avoid Influenza

Many cities began to enforce the closure of public places. In recent news, the parable of Philadelphia and St. Louis have come up frequently. Philadelphia didn't shut down public spaces and in fact held an enormous parade, despite the risk. Within three days, people started dying. St. Louis, by contrast, took extraordinary measures to reduce crowds in public spaces, in the face of intense criticism, but had much lower infection and death rates. New York City, although the most populous city in the nation at the time, fared better than neighboring Philadelphia and Boston for two reasons. First, as the major maritime port for the whole Eastern seaboard, it started quarantining influenza cases as early as August, 1918. Second, the New York City Board of Health in early October recategorized influenza, allowing it to be reported as other infectious diseases. This allowed the city to monitor the situation and make decisions such as a staggered business schedule to reduce traffic on public transportation. On October 15, 1918, the New York Times published "Will District City in Influenza Fight," outlining how the city was to be divided up into districts for better organizing. That day, there was a meeting of the Emergency Advisory Committee, including Dr. Lee K. Frankel, who was at the meeting to represent social services organizations in the city. Of the plan to district, he said, "We shall try to find districts with a physical plant where cooking can be done, so as to supply families where there is illness, and the people are unable to care for themselves in connection with supplying food." This is one of the few indications of city-wide organization of cooked food for victims of influenza and its effects. But the pandemic did have a huge effect on the general population, not the least of which was orphaning children and leaving families without a breadwinner. From the 75th Annual Report of the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor [what a name!]: “In handling the influenza epidemic, the report says, the association tackled one of the heaviest problems it has ever had to face in its seventy-five years. As an indication of the widespread effects of the disease the report points out that during the epidemic it cared for 355 families which had never before received aid from any relief organization. From Oct. 1 to March 1, the association took charge of 600 homes where influenza was prevalent. The work still continues. The association is spending $3,000 a month to care for families whose wage earners died during the epidemic. "In reviewing the year’s work, Bailey B. Burritt, the general director, in reference to the influenza epidemic said: “This has meant greatly increased drafts upon the energies of our nursing and visiting corps. It has meant many additional families which have had to be cared for, and some of these families will have to be cared for for many months because of the death of the breadwinner. It has meant the opening of an additional convalescent home for the after care of influenza cases. It has meant also greatly increased expenditures." At Vassar College, one of the Seven Sisters colleges where upper class white women attended, was also involved with pandemic relief efforts. In the November 27, 1918 issue of Vassar Miscellany News, the weekly(ish) Vassar campus newspaper, Helen Morton, Chairman of the General Service Committee of Christian Association, wrote an article entitled "The Epidemic That Was:" "Perhaps you remember? Yes, and the Poughkeepsie people probably do too! Poughkeepsie was well organized to meet the emergency and they were kind enough to let us help where we could. The College as a whole responded wonderfully. Old clothes fairly showered into the box in Main, mixed with toys for the orphans at Wheaton Park. Sheets monograms and all were sacrificed at a moment's notice. Hundreds of swabs and masks were made within half an hour; dozens of night gowns and a few layettes were made within a week. Six hundred odd dollars were collected in three days. One sick freshman even sent a generous contribution from the Infirmary for those who had influenza. With this money We were able to contribute to the support of the City Club "Kitchen." We were able to send food there every day: vegetables, cereals, orange juice, custards, etc.: we were able to help Miss Oxley with her splendid work in Arlington, to help the Associated Charities, and now we can start in on the reconstruction work with substantial support. The Associated Charities said—"It has given us the greatest pleasure to serve as stewards of the Vassar girls in the distribution of the comforts you gave us, and we are anxious to pass on to the owners the grateful thank- of the recipients." Members of the faculty helped us out in carrying things to and from town, and a few, willing martyrs, allowed their car- to be used for everything imaginable. In fact, everybody seemed willing to pitch in and work wherever they were given an opportunity. Was the college always so wonderful — or is the power to adapt ourselves to an emergency, which was so apparent during those trying weeks, one of the lessons of the Great War?" It's not clear why the article is written in the past-tense, as the pandemic continued for several months after November, but perhaps the worst was over in Poughkeepsie by that point. In the December, 1918 issue of Vassar Miscellany News, The Associated Charities of Poughkeepsie wrote a thank-you letter to "the young women of Vassar College," for their donation of $147.59, which was used to purchase food for needy families in the city for Thanksgiving dinner. Elsie Osborn Davis, General Secretary of the Associated Charities wrote, "Many of these families were either past sufferers or still convalescent from the influenza epidemic. *** In no instance where we gave was there an able-bodied man in the family. Households were either fatherless, or else the wage earner was hopelessly ill in hospital or sanitarium, or languishing in jail, or still convalescent from influenza." Although there is a fair amount of information about responses to the epidemic itself, and some references to the fact that food was needed or was delivered, very little is mentioned of what food was used for patients during this time. Cooking for patients at this time was generally called "invalid cookery" (invalids are sick people, rather than people who are not valid). Typical invalid cookery in the early 1900s was focused on soft, liquid, and/or easy-to-digest foods including beef tea and other meat broths, blanc mange and other milk-based puddings, eggs, and cooked cereals like farina (aka cream of wheat), oatmeal, and milk toast. In January, 1919, the American Journal of Nursing published an article titled, "Food Conservation and Invalid Cookery." Although the war officially ended in November, 1918, voluntary food conservation was urged well into 1919 to help feed the Allies - and defeated Germany - through the winter. Author Alice Urquhart Fewell, a home economist who specialized in invalid cookery, outlined how cooks may deal with rationing, including how to cook cornmeal instead of wheat cereals, to use chicken and eggs in place of beef and to avoid other protein substitutes as being too difficult to digest, and how to use sugar substitutes like honey, corn syrup, and maple sugar. In North Carolina, nurses and invalid cooks suggested that patients with fevers be fed an all-liquid diet, advice that was repeated elsewhere. In addition to beef or chicken broth, buttermilk, and malted milk, albumen water was also suggested. Albumen water is water mixed with raw egg white, and sometimes fruit juice, and served chilled. It was sometimes recommended as an alternative to milk for children. Gelatin was another popular suggestion for invalids as it was easy to swallow and gentle on the stomach. Perhaps the best-known resource available to women and nurses during the Spanish Flu epidemic was written by a very famous person indeed. In 1904, Fannie Merrit Farmer (yes, that Fannie Farmer) published "Food for the Sick and Convalescent." Farmer herself suffered a "paralytic stroke" as a teenager and was forced to drop out of school as she convalesced. She eventually relearned how to walk, though she walked with a limp for the rest of her life and used a wheelchair near the end of her life. Perhaps because of this, she became an expert in invalid cookery and was a frequent lecturer on the topic at the Harvard Medical School. Farmer's invalid cookery is very typical of the period, with its focus on broths and other fortified liquids, cooked grain dishes, eggs, custards, fruits and fruit juices, jellies (gelatin), and frozen desserts, with forays into meat, vegetables, and breads. What is unique about this cookbook is the amount of scientific material in it. Farmer's very first chapter starts in on the current, up-to-date nutrition science of the period, outlining information about essential minerals (we hadn't quite discovered vitamins yet) and listing a chart created by William O. Atwater, an influential nutrition science and the person who turned the calorie not only to use in nutrition science, but also into a household term. Today, we know that this chart isn't QUITE right, although it is on the right track. For instance, "albuminoids" is an old-fashioned term for what today are called "scleroproteins," such as collagen, elastin, and keratin - the insoluble structures of proteins. Farmer also discusses how the body absorbs and metabolizes proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. Her second chapter is all about calories, and even includes a math equation for how to determine the caloric values of any food. Her third chapter discusses digestion (a favorite topic of dyspeptic Victorians), and chapter four, which is quite short, puts forth the somewhat radical idea that eating wholesome food, well prepared, and plenty of rest, fresh air, and exercise were far more essential to good health - preventative medicine, if you will - than simply trying to correct existing diseases with drugs. This scientific approach is, of course, entirely on purpose. Not only was Farmer the kind of rigorous, exacting cook that gave us level measurements, she was also clearly extremely interested in nutrition science and wanted to share what she had learned with her thousands (if not millions) of readers. In part to convince them of her authority on the subject, but also I think to give women the tools they needed to care for their own families, or to pursue careers as nurses. Chapters five and six focus on the care and feeding of infants and children and it is not until chapter seven that we finally start to discuss the ideal diet for the ill, including pictures of some very interesting specialized dishware and glassware for feeding prone patients. Some of Farmer's recipes are not as typical as you might expect. For instance, in the chapter on milk (then considered a "perfect food" for its composition of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats), Farmer touts the benefits of koumiss, kefir, and matzoon - all fermented dairy beverages which Farmer claims are more digestible than straight milk. Which, to be fair, they probably were, not the least of which because the vast majority of milk available to Americans at this time was raw and unpasteurized. Even alcohol has a role to play in Farmer's cookery for the sick, and alcoholic beverages mixed with milk and/or eggs (milk punch, eggnog, hot cocoa with brandy are a few examples). Perhaps the most enduring advice from Farmer is that not only should food be digestible and healthy, it should also LOOK and TASTE good as well. A lesson that a lot of hospitals today could learn from. Fannie Merritt Farmer and other home economists and nutrition scientists were all part of the same movement that led American epidemiologists to try to innovate and find cures for pandemics like the Spanish Flu. The Progressive Era was a time when Americans were trying more than ever to understand the world around them and find ways to cure the physical and societal ills of a nation still dealing with the excesses of the Gilded Age. Although they met with varying success, and many of the upper middle-class white professionals leading the charge were far from perfect, they did make strides. The lessons of Spanish Flu were immediate. In New York City, on November 7, 1918, just days before Armistice, the New York Times published an article entitled "Epidemic Lessons Against Next Time." In it, New York City Health Commissioner Dr. Royal S. Copeland outlined the successes of the city's response, including the immediate quarantine of any cases arriving in the Port of New York by ship, which likely helped curb the introduction of influenza into the city. But most successful of all, perhaps, was the public-private partnership that resulted from the cooperation of private voluntary and relief organizations and city government. Including the mobilization of the Mayor's Committee of Women on National Defense, and its sub-committee on food, to organize food production and cooking for the designated district centers - often located in church basements or settlement houses - and the Automobile Committee, in which wealthy New York women used their automobiles to deliver the food to households in need. The Henry Street Settlement, founded and led by public health nurse Lilian Wald, was singled out in the article for special commendation. The Henry Street Settlement still exists today. The lessons of cooperation, faith in the scientific method, and reliance on experts are all important ones to remember today. As always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed