|

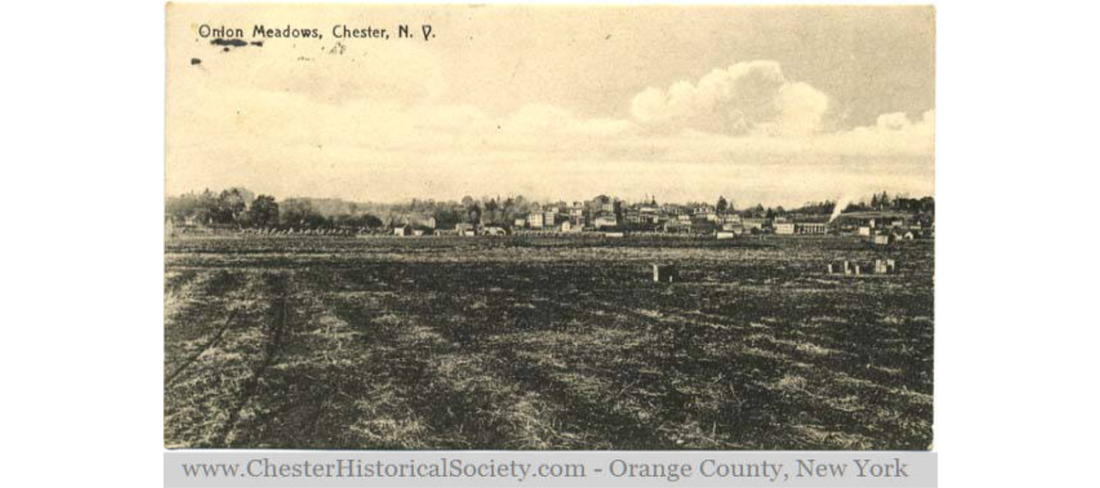

Okay folks. Here's where the history gets real. I've felt often in the last several years that the events of the 1910s were being mirrored in the events of the 2010s. Case(s) in point: rising income inequality, issues with immigration, the vilification of socialism, women's rights, Civil rights, voter suppression, marches for social justice - all these things happened in the 1910s and are happening again today. But one thing I did NOT expect to see, was this recent article from Civil Eats, outlining the struggle of onion farmers, particularly those practically in my own back yard in the black dirt region of Orange County, NY, as they deal with plummeting wholesale prices - so much so that a federal inquiry has been ordered. What. This is straight out of 1916 and my book research. Government inquiries and all. You see, in the winter of 1916/17, food prices had gone up exponentially and working class women in New York City, mostly Jewish women on the Lower East Side, staged food boycotts of a variety of produce, including onions, to protest prices that had doubled or tripled in a matter of weeks. Prices did lower eventually, but not before onions were virtually rotting in railroad yards and warehouses. Farmers in the black dirt region struggled to deal with the surplus and turned to other options as a means of potentially saving their quite perishable crop. Here are some excerpts from my book about the both sides of the situation: Pushcarts remained in service for the time being, however, and Jewish women in particular had had enough of rising prices. Mere months ago their husbands’ wages had bought plenty of vegetables with room for a shabbos chicken and other occasional luxuries. According to a New York Times investigation, February of 1917 left many families barely subsisting on coffee, tea, bread, and rice. Most could not afford potatoes, much less meat. Laborers who used to eat onion sandwiches every day for lunch could now not even afford onions. Wages had to be used for rent, wood or coal for heat, and clothing in addition to food. For many households, food was the one budget item with some wiggle room. But now their budgets were squeezed beyond bearing. Those making ten dollars or more per week were scraping by. Those making less were forced to rely on family members or charity to survive.[1] To working families, the fact that their circumstances had not changed but they suddenly could not afford even the cheapest of foods was not only a hardship, it was an affront to the promise of capitalism. Some families coped by taking on extra work; others coped by eating less or lower quality food. Some grew desperate as “investigators for the city’s charity department found people eating ‘decayed’ potatoes and onions,” although perhaps investigators’ definitions of “decayed” differed somewhat than those of the poor. For many, protest was the best coping mechanism. By February 20, 1916, the Jewish women of the Lower East Side, assisted to some extent by Socialist political groups, organized neighborhood boycotts to try to drive prices down. The violence with which these women enforced the boycotts—assaulting those who broke the boycott, destroying vegetable carts, and attacking storefronts—shocked Progressives and the general public alike.[2] By noon, the boycott had swelled its ranks with poor and working class women and their children who clamored at the gates of Mayor John Mitchel of New York City, holding up their babies and demanding bread. Mitchel refused to meet with them, suggesting that representatives meet with him the following day. The authorities, unable to solve the food price issue and at a loss when it came to dealing with violent and rioting women, did little except arrest and jail the rioters. Most of the women arrested in New York City were later broken out of jail by their free counterparts.[3] Perhaps inspired by the women of New York City, food boycotts and rioting quickly spread across the country. On February 21, riots broke out in Philadelphia; on February 22, in Boston. On February 23, newspapers reported that people in Alabama and Mississippi were near starvation as "for weeks only 6 per cent of the usual allotment of railroad cars” had been able to move food into the region. In New York City on February 22 and 23, there were poultry price demonstrations. In one week the price of poultry had risen from 20 or 22 cents per pound to as high as 32 cents per pound—a 45 percent increase. On February 25, 5,000 people “leaving a protest rally at Madison Square, marched upon the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, demanding food.” Demonstrators also attacked wealthy motorists. One driver, “fearing injury at the hands of the mob, put in high speed and went pell mell through the crowded street,” injuring at least one hundred women and some children. In Philadelphia, food riots resulted in one man being shot by the police and an old woman being trampled by a mob, while furious mothers declared a school strike. In Cincinnati, community leaders called for a boycott of butcher shops. In Chicago, settlement workers reported acute suffering among the city’s poor. High food prices and fuel shortages gave rise to “[r]umors of foreign influence,” which prompted a Justice Department investigation. The investigation later found “no plot” in the food boycotts, only hungry people.[4] The rioting and protests in New York continued on March 1, which the socialist daily paper New York Call called the “worst rioting” yet. Nearly one hundred people were arrested as grocery stores across the Lower East Side were attacked. On March 3, butchers stabbed a baby and an old woman in two separate protest incidents. In an effort to quell the boycotts and alleviate hunger, authorities tried a variety of ways to bring food into the city. Some Progressives tried to shift the diets of poor and working-class Americans to nutritionally equivalent but cheaper and more readily available substitutes, but to the boycotting women this was offensive. “We don’t want their oleomargarine. I could buy butter once on my husband’s wages – I don’t see why I shouldn’t have the same to-day,” said Mrs. Ida Markowitz at a protest. Other women felt the same—“Even two months ago it wasn’t so hard as it is today.” Other Progressive reformers tried to get their wealthy friends to “subscribe” to their efforts to replace middlemen with themselves – to personally buy up produce and have it shipped into the city to sell at below market costs, with the assurance that subscribers would get their money back, of course.[5] The biggest blunder by wealthy Progressives was perhaps that of George Perkins, head of New York City’s Food Committee, who “sent 14,000 pounds of smelt into the city on motor trucks, [but] angry East Side shoppers ‘who suspected Wall Street and did not want smelts, anyhow, mauled the sellers and returned some of the fish to their native element through open manholes.’” Dr. Haven Emerson, head of the New York City Health Department, nearly provoked another riot on March 3 when he told 2,000 East Side residents “to use milk instead of eggs and rice rather than potatoes and not to intrude their European habits into the United States.” An editorial in the New York Call, pointed out that high use of cheaper substitutes was far more likely to simply drive up the prices of said substitutes as demand increased. Many suspected that suggested substitutes were not only a deflection of the larger high cost of living problem, but also covert (and not so covert) attempts by Yankee Progressives to Americanize and assimilate the food habits of immigrant communities.[6] In New York, the boycotts and riots eventually worked. Or so it seemed. In the weeks between February 20 and March 11, pushcarts disappeared from the streets, vendors “slashed prices to save their stocks from spoilage . . . Onion shipments accumulated unsold at wholesalers’ wharves.” By March 11, potato prices had fallen from eleven cents to six cents per pound. But by March 25, New York State Agriculture Commissioner Charles Wilson reported that meat, bread, and vegetables like potatoes were likely to remain scarce, owing to a poor potato and vegetable crop in 1916 and encroachment on cattle range lands in the west. Although prices were dropping from their mid-winter highs, the high cost of living and food price problems remained fundamentally unresolved. [7] [1] “Food Problem Real to East Side’s Poor,” New York Times, February 25, 1917. [2] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 226; Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 258-259. [3] Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 255-285. [4] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 223-229; Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2008), 23; “No Plot in Food Riots,” New York Times, February 24, 1917. [5] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 228-238; As quoted in Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 262-263. [6] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 234-235. [7] Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 259; “Sees No Hope of Drop in Prices of Food,” New York Times, March 24, 1917. For the onion farmers, it was a different story. While their crops were rotting at warehouses, they were searching for alternatives to save the crop. From a different chapter in the book: One of the most popular topics of the OCFPB’s 1917 “Conservation Special” was the premise of grinding potato flour in the home and on the farm. Community dehydration plants and homemade kitchen driers were enthusiastically received, especially in the Pine Island, “black dirt” area where onion and potato farmers were hardest hit by boycotts and transportation issues.[1] Potato flour was being touted as a substitute for or additive to stretch wheat flour, which Herbert Hoover had asked housewives across the country to conserve through his “Wheatless Wednesdays” campaign. In her Erie Railroad Magazine article reporting on the “Conservation Special,” Gillian Bailey wrote, “That we brought encouragement and help to the large market growers is evident by the fact that we are expecting at least three commercial dryers to be run . . . and when these three huge machines are being run to their full capacity I shall feel that Orange county will be doing her bit.” [2] Indeed, there was a great deal of interest in installing community dehydrators all over Orange County. The mayor of Middletown, N.Y. was “so interested in the possibility of a local plant” that he coordinated with the Middletown Chamber of Commerce to discuss. Staff from a local farm belonging to the Department of Correction of New York City spoke with Mrs. Andrea about preserving produce like corn, beans, and tomatoes “until markets for them could be found.” Mrs. Andrea was the OCFPB’s at-large home economics expert who had published a book on food preservation through canning and later went on to publish another on dehydration and drying.[3] Individuals were also interested in dehydration. The OCFPB’s Mrs. M. C. Migel said that “a community dryer is to be installed on her estate at Monroe, N.Y., as an incentive to others. Mrs. H. D. Pulsifer, who owns the 700-acre Houghton farm, at Mountainville, N.Y., is another person who showed interest in the community dryer.” Port Jervis, too, showed a great deal of enthusiasm in the potential of a community dehydrating plant. In a letter to Mrs. Bailey about her impending magazine article, a representative from the Erie Railroad wrote congratulating her about the press coverage of the train, including this tidbit, “Port Jervis, you will note by reading the Union report, is deeply interested and its business men have taken up the question of a community dryer.”[4] Unfortunately for Gillian’s optimism, community dehydration plants did not take off in Orange County as planned. The Port Jervis Union recounted the decision, indicating that a large commercial dryer was too expensive. “After a long discussion, it was decided that Port Jervis and the adjacent farming territory was not large enough to support such a plant.” Indeed, although homemade dryers seemed popular and commercially made ones could be had for as “little” as five dollars, the big commercial dehydration plants proved out of reach for most communities. The narrow profits to be made on dehydrated vegetables just could not warrant the up-front expense. As the war wore on and agricultural production improved, the demand for dehydrated foodstuffs seemed to decline. Perhaps the length of time to dehydrate and the difficulty in reviving dehydrated vegetables, in particular, made the process less palatable to farm wives and individuals. Canning took less time, and the results were much easier to use – just heat and serve for most vegetables, and canned fruits could be eaten straight from the jar. The commercial market for dehydrated vegetables also did not seem particularly robust, and thus could not support the expense of large-scale dehydration.[5] [1] Bailey, “Waste Not, Want Not” Erie Railroad Magazine, 391; “Farmers Interested In Vegetable Drying,” Evening Telegram (New York), July 5, 1917, p. 4. The “black dirt” region of Orange County is a prehistoric peat bog where many a mastodon skeleton has been discovered. This land was sold to Bohemian and Polish immigrants by speculators in the 19th century who deemed it worthless, but the immigrants had experience with draining wetlands to make rich farmland. The topsoil in this region is still today up to 30 feet deep. Special horse shoes were developed to keep them from sinking as they plowed, and modern tractors must have dual tires and cannot be left in the fields overnight. [2] Gillian Webster Barr Bailey, “Waste Not, Want Not,” Erie Railroad Magazine 13, no. 7: 430. [3] “Preached Gospel of Dehydration to 7,000 Persons,” Herald (New York City), July 8, 1917. [4] Ibid.; Erie Railroad Company to Mrs. Bailey, July 9, 1917, Orange County Food Preservation Battalion Scrapbook 1917-1919, Archive, Museum Village, Monroe, NY. [5] “Chamber of Commerce Discussed Drying Plant – City and Community Not Large Enough To Support the Proposition,” Port Jervis Union, undated, Orange County Food Preservation Battalion Scrapbook 1917-1919, Archive, Museum Village, Monroe, NY. Of course, onion farming still happens in Pine Island and Chester and other black dirt towns, as mentioned in the Civil Eats piece. For more about the farming itself, check out this piece from the BBC. And, if you'd like to read the book chapters these excerpts are from, become a member of The Food Historian and you can read to your heart's content in the members-only section of the website. Join today or support us on Patreon.

0 Comments

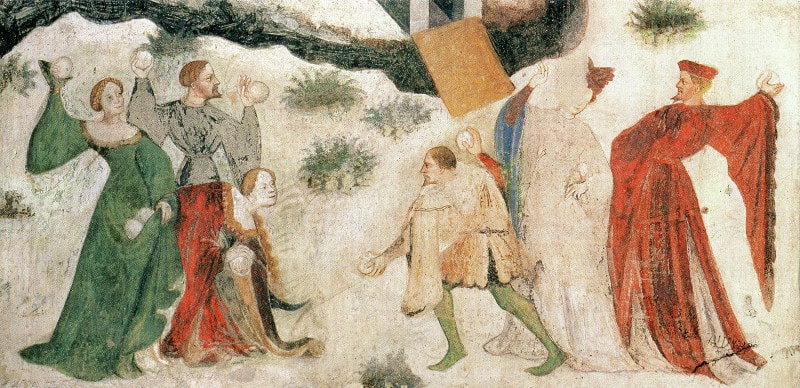

Happy Valentine's Day, everyone! Although Valentine's Day fell on a Friday this year, I had the day off from work (because I worked last Sunday). But despite that, I had a fairly lazy day. Slept in, didn't get out of jammies until noon, and then ran errands all afternoon before completing our annual Valentine's Day rite - NOT going out for dinner. Yes, that's right. For the first few years of our coupledom, my husband and I got gussied up and tried fancy restaurants with special Valentine's Day meals. It was incredibly expensive and not a great experience. So, a few years ago, I decided that at-home meals were best. Of course, typical turn-of-the-last-century holiday meals were often based around a color theme, thanks to home economists. But rather than go the route of pink-tinted mayonnaise and radish roses, I decided that the perfect way to keep things to a very Valentine-friendly red-and-white color scheme was to make a heart-shaped pizza, with red and white heart-shaped toppings. I won't give a recipe, largely because I used store-bought dough and store-bought sauce to make it. But I will say prepare to use a whole pound of shredded mozzarella and set your oven to 450 or 475 F for the best pizza baking experience. My last word of advice? Don't grease your pan - use semolina flour to dust the pan and/or your work surface - it makes a lovely crunchy crust, and is traditional. Years ago Chad got me a pizza stone and peel, and although I've only used it a few times, I thought I would give it another go. I normally make two pizzas on two sheet pans and it works great. I always make two pizzas because they're never as big as the kind you get from a pizza parlor and we like to have leftovers. Lots of semolina flour was in order to make wiggling the raw dough off of the peel and onto the hot stone work, but work it did. The only downside? Because the stone is smaller than a sheet pan, I wasn't able to make the pizza as thin as we like it - and the crust really puffed up. Which wasn't bad, I just prefer it the other way. Once we chowed down on some pizza, I decided to bake a cake. But, because I'm me and typically lazy, I thought Lazy Daisy Cake would be perfect. But also because I'm me, and I can never resist tinkering with recipes (and because I'd bought several quarts of fresh strawberries), I added a layer of strawberries to the bottom of the pan. In retrospect, should have mixed them in, but still delicious how it turned out. I first learned of Lazy Daisy cake from Marion Cunningham's lovely cookbook, Lost Recipes: Meals to Share with Friends and Family, but it's a 1920s-era staple. I made it for my 1920s Garden Party a few years ago and it was a big hit. But! a 9x13" pan only went so far with that crowd, and people love it, so always make more than you think you'll need. Lazy Daisy Cake is a type of hot milk cake - a type of sponge cake that combines whole whipped eggs with baking powder and hot milk to give it a lovely lift and a springy texture. The "lazy" part is two things - first is you don't have to separate the eggs before you whip them (although the mixing is anything but "lazy," especially if you are stubborn and do it by hand like I do). Second is the topping - a mixture of butter, brown sugar, shredded coconut, and heavy cream that gets popped under the broiler to caramelize before serving. Which is far easier than making a frosting and then frosting a layer cake. It's certainly not as pretty as a frosted layer cake, but it tastes fantastic - well worthy of any Valentine. Of course, if you'd like this the pure way - leave out the strawberries, or serve them cold on the side. My husband likes this with liquid cream AND whipped cream (and, sometimes, so do I - it's that dairy farmer heritage), but just about any dairy topping is delicious. My version is based on Marion's, but doubled. Lazy Daisy Strawberry Cake4 eggs 2 teaspoons vanilla 2 cups sugar 2 cups all-purpose flour 2 teaspoons baking powder 1/2 teaspoon salt 1 cup milk 1 stick (1/2 cup) butter (2 tablespoons, then 6 tablespoons) at least 1 quart fresh strawberries (optional) 6 tablespoons brown sugar 4 tablespoons heavy cream 1 cup shredded unsweetened coconut (or finely chopped pecans) Preheat the oven to 350 F. Butter and flour a 9"x13" metal pan (do NOT use glass!). Beat eggs and vanilla until thick, then gradually beat in sugar until very thick. Add flour, baking powder, and salt all together, then stir into egg mixture until smooth and thick. Heat milk and 2 tablespoons butter in a saucepan over medium heat until butter is just melted. Meanwhile, wash, hull, and cut strawberries into quarters (cut the big ones into sixths). When butter is melted into milk, pour hot into batter and stir well until fully combined. Either stir in strawberries, or place in bottom of pan and pour batter over. Bake immediately for 30-45 minutes or until top is golden brown and springs back when touched. While cake is baking, take the saucepan from the milk mixture and add remaining butter (6 tablespoons), brown sugar, cream, and coconut (or pecans) and heat until butter and sugar are melted, then remove from heat. Do not boil. When cake is done, turn off oven and turn broiler on low. Spread the top of the hot cake with the coconut mixture, then broil for about a minute (watch it - it burns easily) until the coconut mixture caramelizes. Remove from the oven and let cool before serving with the dairy topping (liquid cream, whipped cream, milk, ice cream) of your choice. Or eat plain. What did you do for Valentine's Day? Did you eat at home and cook or bake something special? Tell me in the comments! And, as always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. So I had myself a little Medieval-themed birthday. Let's be honest - I wanted to wear a pretty Elven Princess dress and a tiara for my 35th birthday (Middle Ages was definitely a pun that was used). I didn't decorate the house much, and to be honest you're lucky I snapped as many mediocre photos as I did (too busy having fun!). Food-wise, I tried to stay away from any Western Hemisphere foods, and to create dishes based on peasant foods, rather than the feast meals of European kings. Some were very ordinary, like store-bought peasant bread and cheese and roasted chicken legs. Some didn't turn out as well as I'd hoped, such as pease porridge with leeks (flavor was good, split peas didn't cook up as smooth as I would have liked - still some crunchy bits). But a few were real knock-outs, so I'm sharing them here. Pate a l'oeufsThis one is inspired by a Tamar Adler recipe by the same name, from her book Something Old, Something New. It's almost certainly a 19th or early 20th century recipe, but it SEEMED Medieval, so in it went. I thought it would be pretty good, and it was, but the party guests LOVED it. A surprise hit. 6 hardboiled eggs 2 tablespoons soft butter 1 cup shredded cheese (I used a mixture of sharp cheddar and jarslberg) 6 green onions/scallions, finely sliced dash olive oil a tablespoon or two of mayonnaise juice of half a lemon salt to taste Halve the hard boiled eggs to remove the yolks. Mash yolks with butter until they make a smooth paste. Finely mince the egg whites and add to yolk mixture with cheese and onions. Add olive oil to moisten and mix well. Add lemon juice and mayonnaise and mix again. Mixture should be thick - like a pate. Salt to taste and serve with crackers - sturdy ones like rye Wasa or Triscuits are best. Red Bean Herbed SaladThis is very loosely based on a similar dish from the nation of Georgia, where they love fresh herbs, garlic, and walnuts. I realize now that kidney beans are actually native to the Americas, so not really accurate to Medieval Europe. But still, shockingly delicious. I actually made it again tonight for dinner, and my husband loved it so much he ate nearly half the bowl. Lol. It's best when eaten with something rich and fatty - like the grilled cheese I made tonight, or like the mushroom pasties I made for the party. 2 cans red kidney beans, drained and rinsed 1 cup minced fresh dill 1/2 a bunch fresh parsley 1 generous handful arugula 1-3 cloves garlic (3 if you like it "spicy") 1 cup raw walnuts more olive oil than you would think more cider vinegar than you would think In a small food chopper, process the garlic, parsley, walnuts, olive oil, and cider vinegar (if you don't have a food chopper, mince the garlic and chop the parsley and walnuts before mixing with olive oil and vinegar). Pour over the beans and minced dill, toss with arugula, and serve at room temperature. Taste and add more vinegar if desired. Alternatively, you can add the arugula to the "sauce" with the parsley. Other options include adding fresh basil and/or cilantro - other popular Georgian flavors. But the dill is the real deal, so don't skimp unless you really hate the taste of dill. Mushroom PastiesI have a lot of vegetarian friends, so instead of making meat pasties, I decided to go with mushrooms. The pastry dough is my go-to for everything and comes from - believe it or not - an old Russian cookie recipe. It's impossible to overwork and although it's more tender than flaky, it's perfect for pasties and slab pies. I made it with half spelt flour so it tasted more authentically peasant-y. For the pastry dough (this will make double what you need for the pasties): 1 pound butter, very soft or melted 1 pound farmer cheese or pot cheese 4 cups flour Cream the butter and cheese, then mix in the flour. Knead until smooth. Let rest while you cook the mushroom mixture. For the mushroom mixture: 2 pints white button mushrooms 2 pints baby bella mushrooms 6 shallots 1 stick butter thyme salt white wine lemon juice In a wide pot (stock pot or dutch oven), melt the butter with the thyme (be generous - mine could have used more) over medium heat. Meanwhile, peel and slice the shallots and add them to the butter. Then rinse and finely mince the mushrooms (this will take a while by hand - feel free to pulse in a food chopper). Cook the mushrooms and shallots in the butter until all the liquid is absorbed (raise heat if necessary), then add white wine and lemon juice in batches, letting the mushrooms absorb between additions. Taste and add salt if necessary. Let cool before filling pastry. Preheat oven to 425 F. Take walnut-sized pieces of dough (about enough to fill your palm when you make a fist) and roll quite thin (not paper thin, but close). Add mushroom mixture, fold round in half, and crimp edges. Place on a large sheet pan and slash the top of the pasty to allow steam to escape. Repeat until the mushroom mixture is gone. This should make about 18 palm-sized pies. Bake 25-35 minutes, or until the crust is golden brown. With the leftover dough, make a pear custard slab pie! Pear Custard Slab PieI was not planning to make this at all, but had some winter (Bosc) pears on hand. Not enough to really fill the pie though, so I added my classic quiche custard ratio spiked with a little sugar and cinnamon. It was a huge hit. I also had some bits of marzipan and candied almonds that I chopped up and added. It seemed Medieval-y enough and everyone loved it. 2 Bosc pears, cored and thinly sliced half a batch Russian pastry crust (above) 2 eggs 2/3 cup milk a tablespoon or so of sugar ground cinnamon to taste Optional: bits of marzipan 1/4 cup candied almonds, chopped Preheat oven to 425 F. Roll the pastry into a sheet large enough to fit a jelly roll pan (1/4 sheet pan). Trim the edges and use the extra dough for the lattice and decorations. Layer the pears in the pan, add marzipan and almonds, if using. Whisk the eggs with the milk, sugar, and cinnamon, then pour over the pears. Add the latticework and bake 30-45 minutes, or until the custard is set and the crust is golden brown. Candied AlmondsWhat Medieval party is complete without candied almonds? This was a super-simple recipe I lifted from the internet. It didn't turn out quite as nicely as I would have liked - the sugar-egg-white mixture made the coating more powdery, which meant lots of wasted powder got left in the pan. And definitely you'll want to use parchment paper on these bad boys, or be prepared to clean up a very stuck-on mess from your sheet pan. But, again, the party guests LOVED them. And while I didn't get a good stand-alone photo, if you're really curious, you can see them in the corner of the first pear custard slab pie photo (and, y'know, all candied almonds look largely alike). 1 pound raw shelled almonds 1/3 cup brown sugar 1/3 cup white sugar 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon salt 1 egg white Preheat oven to 300 F. Whisk egg white until frothy, add almonds and stir to coat, add sugars, cinnamon, and salt, and stir to coat. In a half sheet pan lined with parchment paper, pour the almond mixture out and spread evenly, so that the nuts are all in a single layer. Bake for 30 minutes, then let cool. (I did not stir like the original recipe called for, and it made a big slab.) When fully cool, break apart into individual almonds with hands (if necessary). Eat by the handfuls. Marzipan Stuffed DatesThis is probably the most authentic of all the recipes and it couldn't have been easier. Of course, it helped that I used store-bought marzipan!

2 pints medjool dates 1 tube marzipan Cut dates halfway through, lengthwise, and remove the pits. Take a small bit of marzipan and shape into ovals big enough to fit into the center of the date. Close the edges together, but not so much that you can't see the marzipan. Then try not to eat them all. They are VERY sweet, but also an incredibly delicious dessert and they make everyone ask - why did we stop making these?

It's Black History Month here in the United States, and while I firmly believe that Black history should be studied and celebrated year-round, I thought this would be a good time to highlight some of the good articles and important contributions by Black food historians and cookbook authors.

I'll be sharing articles on Facebook all month, but wanted to make some lists for reference, plus links to lots of great books! The following historians are in no particular order, but you should read about them all! And if you want to support them (and, by extension, The Food Historian), you can purchase one or more of their books! Jessica B. Harris

Dr. Jessica B. Harris is considered one of the foremost experts on African diaspora food and has written a number of books and cookbooks on the subject. In 2019, she was inducted into the James Beard Foundation Cookbook Hall of Fame. She was also featured on "The Food that Built America," along with numerous other television appearances.

She is probably best known for her 2012 history, "High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America," which links Southern (read: African) food traditions back to Africa and their connections to slavery. You can learn more about Dr. Harris on her website, or check out one of her numerous books! Adrian Miller

Adrian Miller is the Soul Food Scholar. He is a certified barbecue judge and culinary historian whose two books, "Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time," and "The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas," have both won numerous awards. He's currently working on a new book, "Black Smoke," a history of African American barbecue culture.

Tonya Hopkins

I first met Tonya as she was recreating a 19th century African-influenced dinner that Black cook Anne Northup (wife of Solomon Northup - of 12 Years a Slave fame) might have cooked while she was working at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City. I had a wonderful time and Tonya lives up to her "griot" name as a fantastic storyteller. Although Tonya has not yet written her own book, she has contributed to numerous scholarly publications. She is also co-founder of the James Hemings Foundation, named after Thomas Jefferson's enslaved, French-trained chef de cuisine, and consultant on the upcoming exhibit at MOFAD, "African/American: Making the Nation's Table."

Michael Twitty

Michael Twitty is a bit unique in this group - not only is he a researcher, cook, and writer, he is also a historical interpreter. Twitty first rose to prominence with his 2013 Open Letter to Paula Deen, calling out her racism and appropriation of African American foodways under the guise of "Southern" food. In 2017, he published "The Cooking Gene," which Twitty calls, "a genealogical detective story, a culinary treasure map, a blueprint for finding your roots, a series of history lessons, a revealing memoir and a spiritual confessional sprinkled with recipes." In 2018, it won the James Beard Foundation's Book of the Year Award. You can read more of his work on his blog, Afroculinaria.

Toni Tipton-Martin

I first heard of Toni Tipton-Martin with the buzz around the publication of "Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks," which was the 2016 James Beard Foundation Book Award winner. I purchased a copy at an OAH conference and loved it. Toni also had a longstanding career as a food journalist and is a cookbook writer as well. You can learn more about her on her website.

Frederick Douglass Opie

Fred Opie (PhD) is a Professor of History and Foodways at Babson College. He has written a number of engaging food histories, including one of Zora Neale Hurston's WPA-era writing on Florida Food. Fred also hosts a podcast and writes extensively about foodways on his blog, in addition to other projects.

Psyche Williams-Forson

Psyche Williams-Forson is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of American Studies at University of Maryland College Park. Psyche is probably best known for her work, "Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power." She has also curated two online exhibits: "Fire and Freedom: Food and Enslavement in Early America,” for the National Library of Medicine and “Still Cookin’ by the Fireside,” an online text and photo exhibition on the history of African American cookery for the Smithsonian Institution’s Anacostia Museum.

Marcia Chatelain

Marcia Chatelain is a Provost’s Distinguished Associate Professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University. She was a Eric & Wendy Schmidt Fellow at New America from 2016-2018. She spent her fellowship year on a book that explores visions of economic and racial justice after 1968 and the fast food industry. That book is "Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America," about building Black wealth and the role of fast food franchising in post-Civil Rights America, and it was JUST published in January, 2020!

Leni Sorensen

Leni Sorensen is a culinary historian and historical interpreter extraordinaire. Consulting with places like Colonial Williamsburg and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, she is an expert on African-American foodways and Virginia cookery, particularly the work of Mary Randolph, who published The Virginia Housewife in 1824. Leni is now retired from museum interpretation, but continues to work as an independent scholar. You can learn more about her via her website. Or, read this great 2010 interview with Virginia Living.

I'm sure I've forgotten a few! If I have, please contact me and I'll update the list. If you enjoyed this list and you want to support The Food Historian (and all these wonderful historians!) you can just click on the cookbook images and purchase their books from Amazon! The authors will get their royalties and The Food Historian will get a small commission.

Or, if you're so inclined, you can join us as a member of The Food Historian. You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed