|

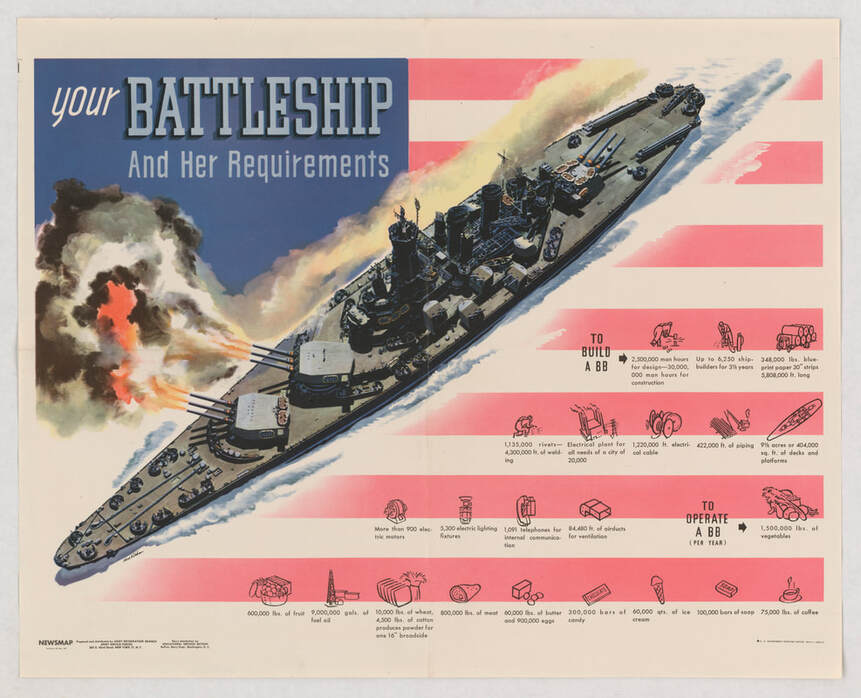

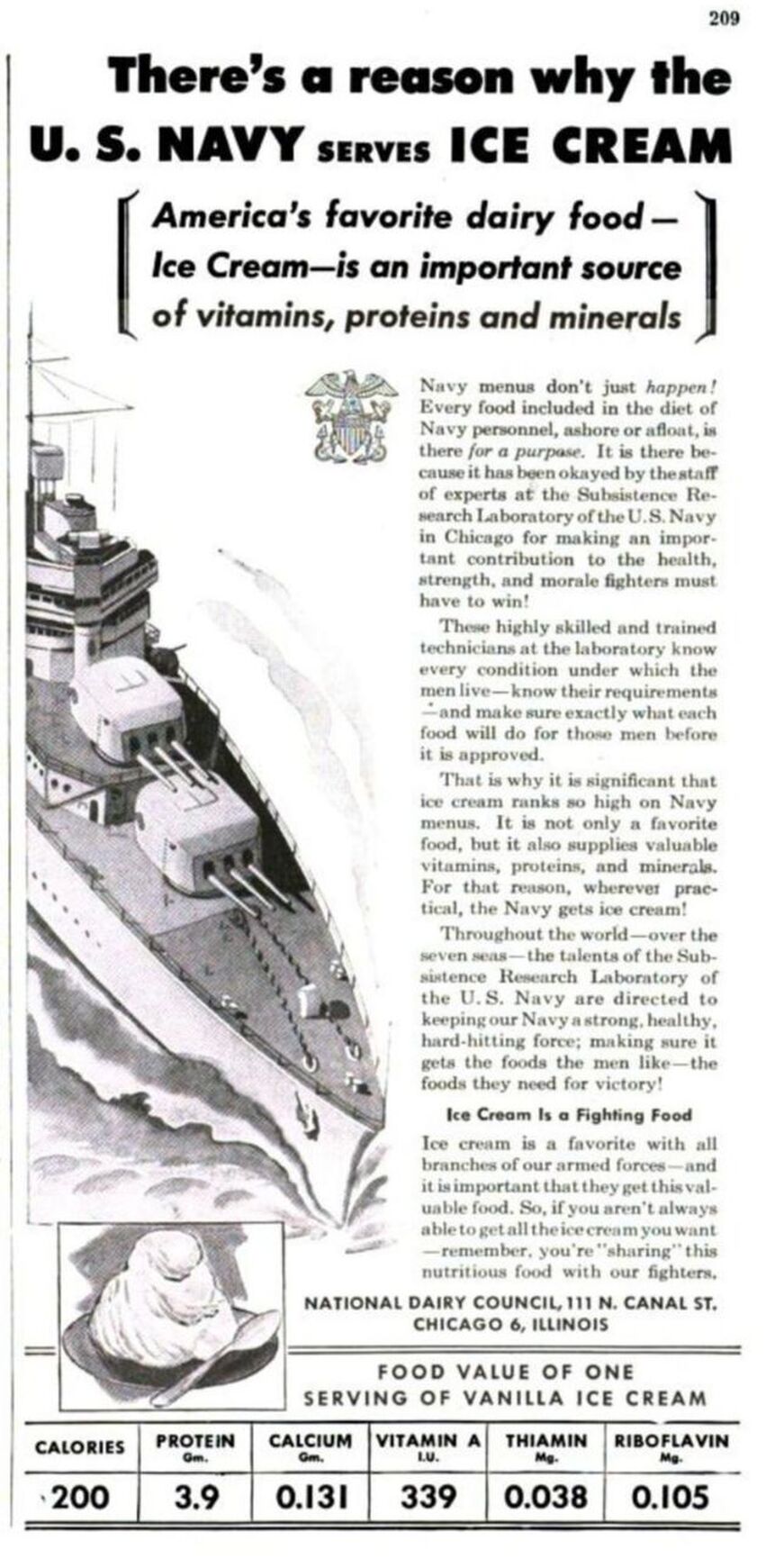

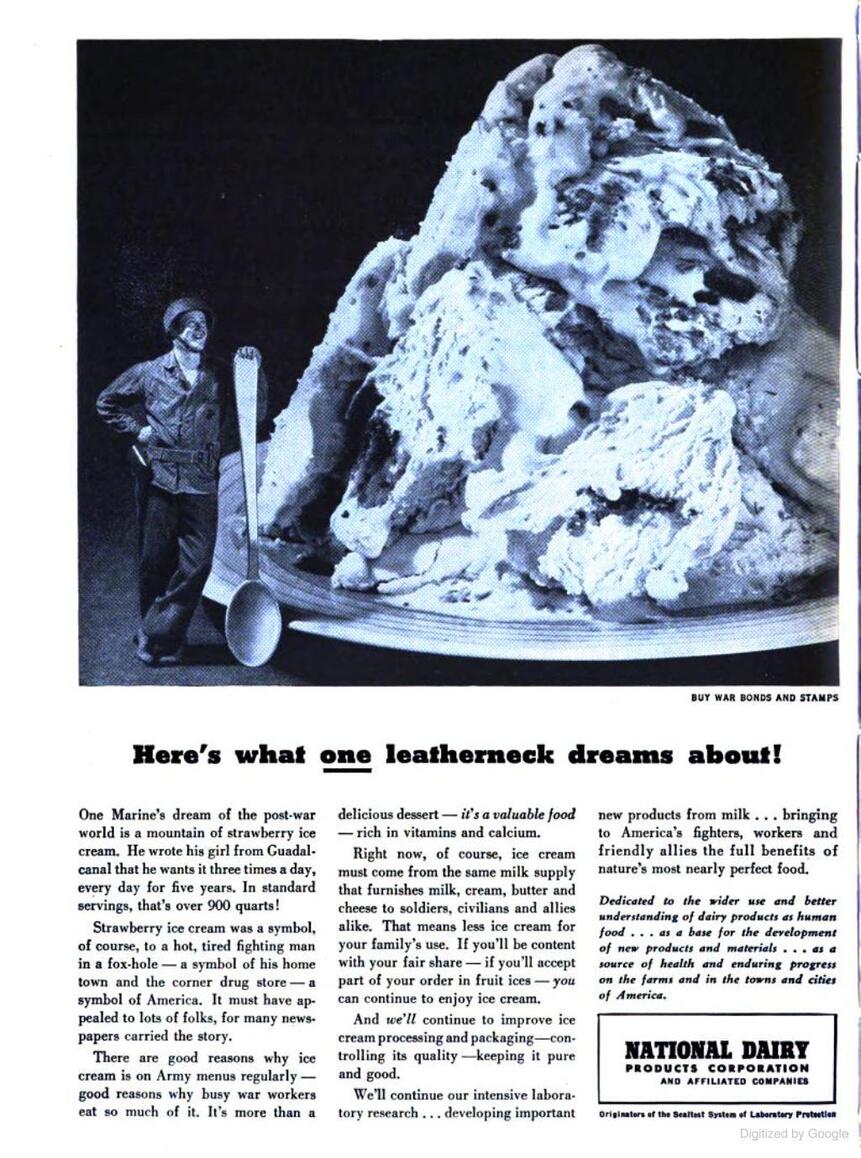

Last World War Wednesday, we looked at the use of ice cream in the U.S. Navy during the First World War, especially aboard hospital ships. Now it's time for a reprise! By the Second World War, ice cream was firmly entrenched aboard Naval vessels. So much so, that battleships and aircraft carriers were actually outfitted with ice cream machinery, and by the end of the war the Navy was training sailors in their uses through special classes. The above propaganda poster, courtesy the National Archives, outlines all of the requirements to build a battleship. "Your Battleship and Her Requirements" may have been targeted toward factory workers, but I think it is more likely this poster was designed to impress upon ordinary Americans the extraordinary amount of materials and supplies needed to keep a battleship in fighting trim. What I found particularly interesting, was that among the supplies listed, alongside fruits and vegetables and meat and even candy, was 60,000 quarts of ice cream! Smaller vessels, such as destroyer escorts and submarines, did not have the space for their own ice cream making machinery, although they did have freezers. In fact, it became common for destroyer escorts and PT boats to rescue downed pilots (the aircraft carries were too big for the job) and "ransom" them for ice cream. Last week a brand new food podcast debuted for American Public Television called "If This Food Could Talk," and I'm so pleased to say I was featured in the first episode, "Frozen in Time: Ice Cream and America's Past." I had a blast doing the research for that episode's interview, which has inspired these two recent World War Wednesday posts. Have a listen if you want to learn more about ice cream in American history, and especially the story of ice cream in the Navy. But while I was doing the research, I kept running across references to ice cream as a health food! The National Dairy Council really leaned into the notion of ice cream and the armed forces. This advertisement reads, "There's a reason why the U.S. Navy serves Ice Cream. America's favorite dairy food - Ice Cream - is an important source of vitamins, proteins and minerals." The ad goes on: "Navy menus don't just happen! Every food included in the diet of Navy personnel, ashore or afloat, is there for a purpose. It is there because it has been okayed by the staff of experts at the Subsistence Research Laboratory of the U.S. Navy in Chicago for making an important contribution to the health, strength, and morale fighters must have to win! "These highly skilled and trained technicians at the laboratory know every condition under which the men live - know their requirements - and make sure exactly what each food will do for those men before it is approved. "That is why it is significant that ice cream ranks so high on Navy menus. It is not only a favorite food, but it also supplies valuable vitamins, proteins, and minerals. For that reason, wherever practical, the Navy gets ice cream! "Throughout the world - over the seven seas - the talents of the Subsistence Research Laboratory of the U.S. Navy are directed to keeping our Navy a strong, healthy, hard-hitting force; making sure it gets the foods the men like - the foods they need for victory! "Ice Cream Is a Fighting Food "Ice cream is a favorite with all branches of our armed forces - and it is important that they get this valuable food. So fi you aren't always able to get all the ice cream you want - remember, you're 'sharing' this nutritious food with our fighters." The National Dairy Council might be just a SMIDGE biased in this regard, but certainly the federal government ranked milk, and by extension milk products, very highly in terms of nutrition during the Second World War, notably as part of the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations. This was almost certainly a holdover from the Progressive Era's take on milk as the "perfect food" - combining proteins, carbohydrates, and fats all in one. We see this in another advertisement, this time by the National Dairy Products Corporation. The National Dairy Council is an industry-funded research and marketing organization. But the National Dairy Products Corporation would later become Kraft Foods. "Here's what one leatherneck dreams about! "One Marine's dream of the post-war world is a mountain of strawberry ice cream. He wrote his girl from Guadalcanal that he wants it three times a day, every day for five years. In standard servings, that's over 900 quarts! "Strawberry ice cream was a symbol, of course, to a hot, tired fighting man in a fox-hole - a symbol of his home town and the corner drug store - a symbol of America. It must have appealed to lots of folks, for many newspapers carried the story. "There are good reasons why ice cream is on Army menus regularly - good reason why busy war workers eat so much of it. It is more than a delicious dessert - it's a valuable food - rich in vitamins and calcium. "Right now, of course, ice cream must come from the same milk supply that furnishes milk, cream, butter and cheese to soldiers, civilians and allies alike. That means less ice cream for your family's use. If you'll be content with your fair share - if you'll accept part of your order in fruit ices - you can continue to enjoy ice cream. "And we'll continue to improve ice cream processing and packaging - controlling its quality - keeping it pure and good. "We'll continue our intensive laboratory research... developing important new products from milk... bringing to America's fighters, workers and friendly allies the full benefits of nature's most nearly perfect food." Here you can see the "perfect food" rhetoric in action! And interestingly, this one touts the role of ice cream in the Army as well. In my opinion ice cream, for all the rhetoric about nutrition, had far more to do with morale than anything else. But there is some truth to the idea that as a dessert it was superior to cake or pie. For one thing, ice cream does have some protein, in addition to a decent amount of fat. Full fat dairy is generally proven to be more filling and satisfying and protein and fat slow down the absorption of sugar directly into the bloodstream, making the "energy-giving" properties of carbohydrates longer-lasting and less likely to make you crash (unlike cake and cookies). That being said, viewing ice cream as a health food is questionable today. But in the period, the discoveries of vitamins and minerals like calcium were cutting-edge, and any food containing those essential nutrients was considered good for you. Ice cream also fit neatly into ideas (unconscious or otherwise) of White supremacy and American (i.e. Anglo-Saxon) culture. As the National Dairy Products Corporation marketing team wrote, ice cream was "a symbol of America." When combined with soda fountains (the wholesome, if sugary, alternative to saloons and beer halls), ice cream seemed to represent the best of America - slim, good-looking, young, White America, that is. Today, ice cream's modern accessibility has given us ice cream alternatives aplenty, especially for folks who can't consume dairy. Ice cream's ubiquity has also meant some of its luster has faded. But at a time of extreme stress - the violence of the theater of war, the privations of home front rationing, the push to mobilize for total war, the fear of invasion - ice cream provided a moment of bliss in the midst of uncertainty. Ice cream is still an essential tradition aboard Naval vessels today. When you're miles from home for months at a time, anything that seems like a treat gives morale a boost. It's still a treasured treat in our household, whether homemade or store bought (if you find yourself in upstate New York - do yourself a favor and seek out Stewart's Shops. They have the best commercial ice cream around). What does ice cream mean to you? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! A special patrons-only post is coming tomorrow with more on ice cream in World War II - this time featuring Elsie the Cow! Join now for as little as $1/month.

Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

1 Comment

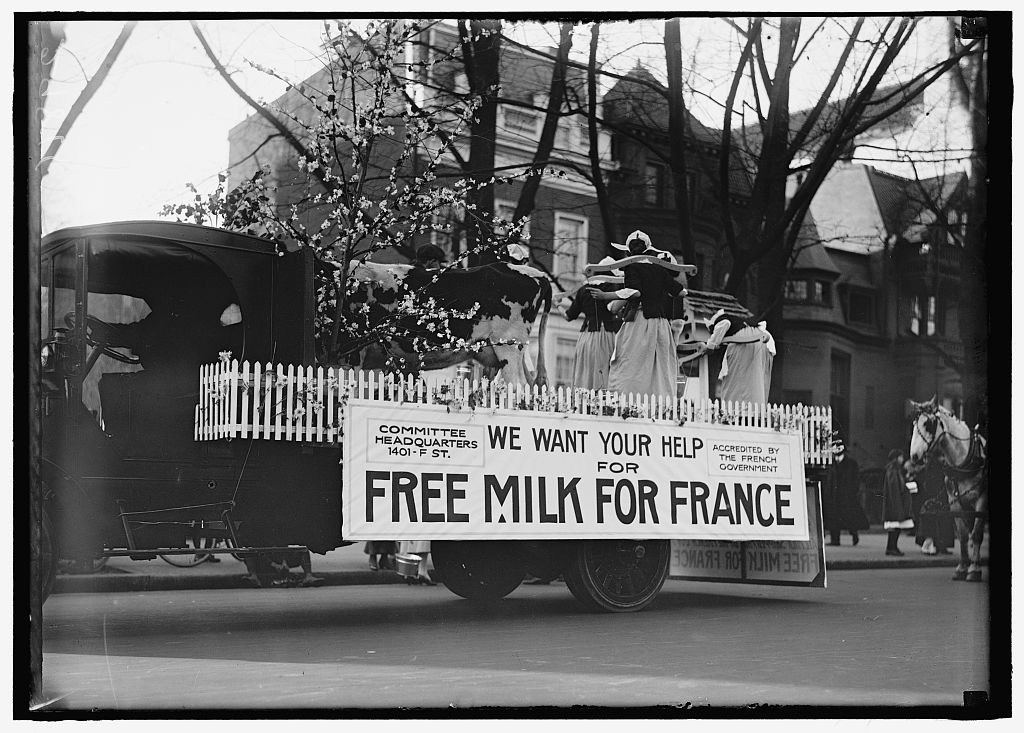

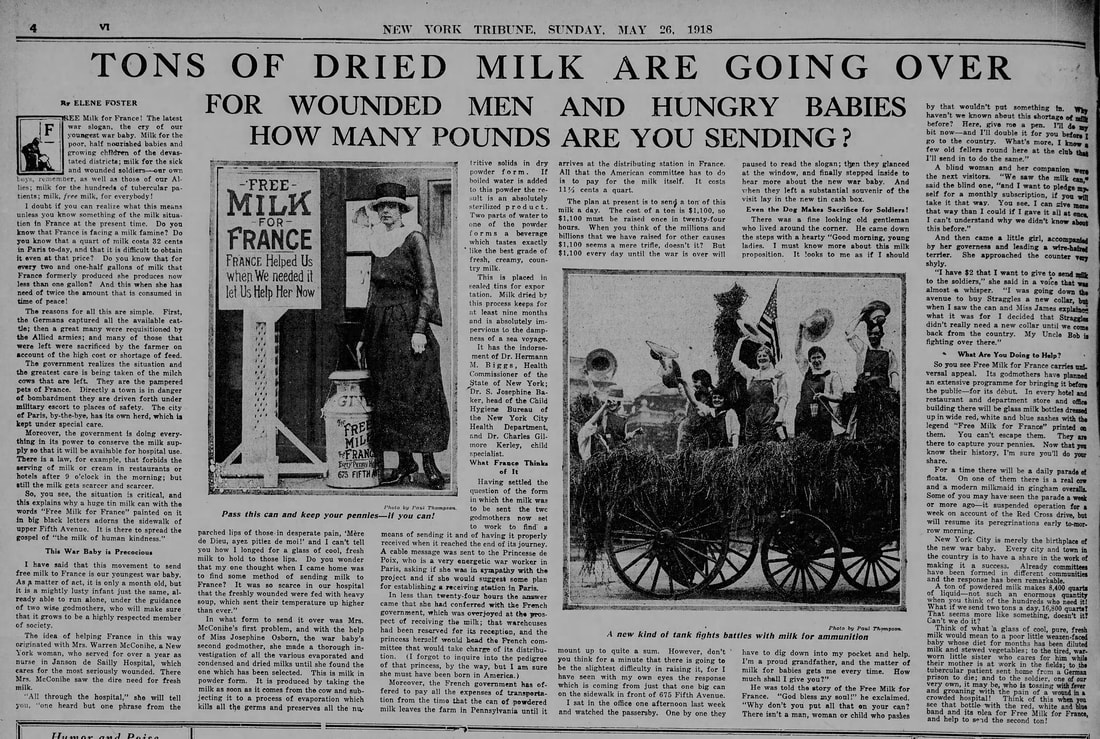

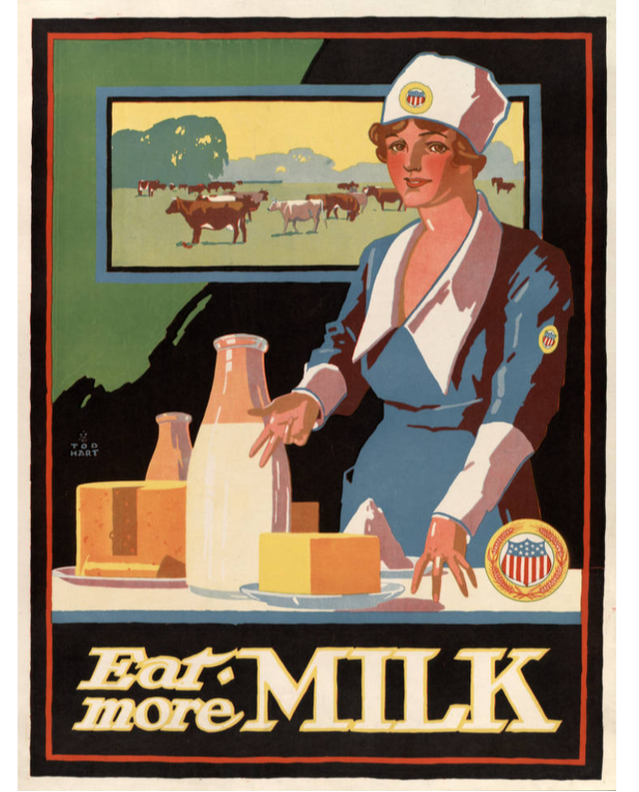

Last week we learned about the big Dairy Exposition during WWI - this week we're examining the Free Milk for France movement, which coalesced about the same time. This propaganda poster by F. Louis Mora from 1918 is one of the more famous of the food-themed propaganda posters of the First World War. In it, a soldier ladles milk out of a large milk can into the bowl of a French child, one of several, accompanied by a wounded French soldier with a tin cup and crutch. Judging by how bundled up everyone is, it's probably winter. Ironically, the Free Milk for France campaign actually focused on provided dried milk. On May 13, 1918, the Committee to Obtain Free Milk for France launched a fundraising parade. "The parade, consisting of two floats and an escort of soldiers and sailors, including a navy band, started from the First Field Hospital Armory at Sixty-sixth Street and Broadway and canvassed the city as far down as the Wall Street District," reported the New York Times the following day. "The money will be used to purchase powdered milk to be sent to France for the use of wounded soldiers, babies, and tubercular patients." In the above photo, a woman dressed in overalls and a straw hat drives a team of horses pulling a large hay wagon. Another woman riding on the wagon is dressed in a military-style outfit holding a small bucket and a wooden shoe - likely soliciting donations. An American flag attached to a sheaf of hay is behind them. The first parade made over $1,000. The group launched another parade a few days later, on May 17th, parading "down Fifth Avenue from Fifty-ninth Street to Twenty-second Street yesterday afternoon." Featuring seven floats, including young society girls "dressed as milkmaids."  Free Milk for France parade, motor truck with a float of milkmaids with a live cow and flowering tree, surrounded by a white picket fence. A large sign reads, "We want your help for Free Milk for France," with smaller notes - "Committee Headquarters 1401-F St." and "Accredited by the French government." Harris & Ewing photographers, May, 1918. Library of Congress. In the above black and white photo, a flat bed truck features a large float carrying a flowering tree, a live dairy cow, and at least five young women dressed as Brittany milkmaids. The edges of the float are surrounded by a white picket fence. On May 19, 1918, the New York Times published "America Sending Milk to France." The article is transcribed below: One of the greatest sources of suffering in France has been lack of milk. The causes for this lack are manifold. In many instances the Germans slaughtered cows for beef whose greater value lay in their milk; in other instances the Government of France requisitioned the animals for army use, and in still others the farmers found themselves forced to kill their cattle on account of the shortage of pasture and fodder. All in all there have been lose to the people of France about 2,000,000 cows, and the main source of maintenance of infants and children, of the crippled and the wounded, the sick and tubercular, lies in milk. At present the death rate of children in France is from 58 to 98 per cent. The number of wounded and crippled needs no repetition here. The increase in the ranks of the tubercular is appalling. Outside Belgium, perhaps, there is no other country which has so greatly succumbed to this disease. The supply of milk in France has been depleted at least 16 per cent. Under present conditions infants must take vegetable stews as a food substitute. What this means to their health and their growth the mortality figures show. Wounded soldiers get heavy soups, which are well-nigh fatal in their effects. The tubercular of France have almost been forgotten. Milk has become a luxury far beyond the reach of the majority of them. In order to do something to meet this situation and to conserve the milk they have, the French Government is taking vigorous measures. Great care is devoted to the protection of milch cows. From bombarded towns, under military escort, two or three at a time are led back to places of safety. Farmers are urged to make all sacrifices possible to provide proper feed for them. Within Paris a herd of cows is kept under civic care. Government restriction now forbids the serving of milk or cream for any purpose in restaurants, hotels, or public eating places after 9 o'clock in the morning. In private homes, rich or poor, milk is only given to young children and the sick. Milk in Paris costs 32 cents a quart, when it can be bought. It was in a desire to do something to change these conditions that Mrs. Warren McConihe and Miss Josephine Osborne organized the Free Milk for France Fund. Mrs. McConihe had seen the soldiers suffering greatly for want of milk, she had seen them grow feverish under the influence of heavier foods. She had seen the Belgian and French refugees almost starved for lack of milk. Upon her return to this country she found that America had enough milk to send some across. Because it requires less shipping space, she chose powdered milk. It is scientifically prepared by subjecting fresh, pure, full-creamed milk to a rapid evaporating process, which preserves the nutritive solids and keeps without ice for months. The milk when prepared costs about 13 cents a quart. There is no other cost. The Government of France has taken over the details of transportation. It is the aim of the organization to send one ton of milk a day. All that is necessary is to mix with hot water. The milk in this form has been recommended even for home use by Dr. Hermann M. Biggs, State Health Commissioner; Dr. S. Josephine Baker of the Child Hygiene Bureau, and Dr. Charles G. Kerley, a child specialist. At a cost of $1,100 a ton of dried milk is sent across, enough to feed 8,400 babies or wounded soldiers or tubercular patients. $52 will send 100 pounds of dry milk or 40 quarts of liquid; $5.20 will sent ten pounds, or forty quarts, and 13 cents will send one quart. The aim of the Free Milk for France organization is to have the nation as a whole respond to its work. Branches are being organized all over the country. The headquarters of the fund is at 675 Fifth Avenue. These two parades, held during the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition, were just the first of a campaign that would last into 1919 and spread across the country. By the end of 1919, there were campaigns in thirty-six states, and the distribution in France was being organized by Madame Foch - wife of French General Ferdinand Foch. The rhetoric around milk and its importance in the diet, especially for children and the sick, would be replicated in the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! This beautiful propaganda poster from the First World War is the result of a controversy. The fresh-faced young white woman in her United States Food Administration-approved food conservation uniform and cap, gestures to a table with an enormous glass bottle of milk, a huge block of butter, a wheel of cheese, and what is either a mound of cottage cheese or some sort of milk pudding. A framed view of dairy cows in a green field floats behind her. It exhorts the reader to "Eat more MILK." But why? Throughout World War I in the United States, dairy farmers struggled. Feed prices went up, and retail prices of milk went up, but the wholesale prices that farmers got from milk dealers and dairies remained static. Despite dozens of local and state and federal inquiries, no single culprit for high milk prices was ever discovered. The result of high prices combined with government advocating for increased production and Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet, particularly for children, meant that by the spring of 1918 there was a serious milk surplus. For several years, the butter, cheese, and condensed milk industries had absorbed the milk surplus, but by the spring of 1918 they were also over capacity. The United States Food Administration, in conjunction with state governments, embarked on a campaign to try to get Americans to consume more milk, with limited success. In May of 1918, New York City hosted the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition at the Grand Central Palace. New York State Governor Charles Whitman opened the exposition, and United States Food Administrator Herbert Hoover also attended. Home economists praised milk-based dishes such as puddings, custards, and the use of cottage cheese and brick cheeses - hence the phrase "Eat more milk," rather than "drink," as drinking cows milk was not common among adults. Cottage cheese and brick cheese were touted as affordable meat alternatives. Despite the classic Progressive Era boosterism, including the attendance of "famous" cows at the exposition, retail milk prices remained relatively high, with seasonal dips in the spring and early summer. Federally fixed milk prices helped solve the problem short-term, but even after the war, dairy farmers were subject to a Congressional investigation to determine whether they price gouged consumers (they didn't), and the right of farmers to form co-ops was in danger of becoming illegal under anti-trust laws. Ultimately, it was falling grain prices and rising postwar demand that evened out prices, although to this day the dairy industry still struggles. Even after the war, Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet persisted, and were recycled during the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. I had a blast and everyone asked such great questions!

In this week's episode, we covered a LOT of ground and discussed how applejack is made, shrub, eugenics, Americanization of immigrants, comparisons between modern issues with dairy farming, dumping milk, and plowing under fields of vegetables and what happened during WWI and the Great Depression, types of dairy cows and how dairy farming works (including a discussion of veal), Victory gardens, agricultural policy history, historic baking, and flips (including Tom & Jerry). WHEW! The hour flew by and I had so much fun. You can watch the whole thing below.

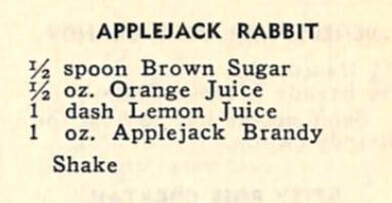

And of course, I made a vintage cocktail! This week's cocktail is the Applejack Rabbit and it comes from the 1946 cocktail book, The Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly.

We talked a little bit about cocktail glasses and serving sizes because of course this week I did NOT use a Collin's glass, but rather a small martini glass. In his introduction to The Rover Bartender, Kelly writes, "As the drinks are shorter now, the glasses for mixed drinks should be shorter and the drink recipes in this book are especially for cocktail glasses of not over 2 1/2 ozs. If a larger glass is used, the proportions will have to rise. You may serve a pony of cognac in a 20 oz. snifter glass, but if a cocktail glass is not near full it is unsatisfactory to the customer." I can certainly agree! But as someone who prefers a cocktail to be only a few ounces, I can't say I enjoy the generally much larger glasses of modern bars and restaurants. They may be easier to handle and clean, but they're too big! Applejack Rabbit Cocktail (1946)

The original recipe is as follows:

1/2 spoon brown sugar (I used about half a tablespoon) 1/2 oz. orange juice 1 dash lemon juice 1 oz. applejack brandy Pour over ice in a cocktail shaker and shake for longer than you think you should to make sure the brown sugar is dissolved. Strain into a small cocktail glass, such as martini glass or old-fashioned champagne glass. Sip cold. Virginia Apple Cake Recipe

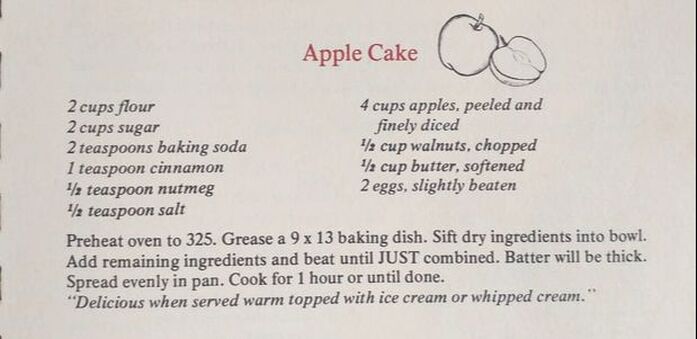

And, since we talked about historic baking, I thought I would share the recipe for apple cake I found recently in my copy of Virginia Hospitality (1976, my copy is the 1984 reprint). This particular Junior League cookbook is quite good with many of the recipes arranged by region and with decent head notes for many. Alas, this "Apple Cake" has neither headnotes nor region assigned. But it looked intriguingly easy and used up quite a bit of apples.

However, as I discussed in the episode, it really is a strange cake. As such, while I've included a photo of the original recipe, I've written my own version to help walk you through how the recipe should work.

2 cups flour

2 cups sugar 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg 1/2 teaspoon salt (note - I would add 1 teaspoon next time, the cake tasted a bit "flat") 4 cups apples, peeled and finely diced (about 3 medium apples) 1/2 cup walnuts, chopped 1/2 cup (1 stick) butter, softened 2 eggs slightly beaten Preheat oven to 325 F. Grease a 9"x13" baking dish (I used metal). Whisk dry ingredients in a bowl, then add apples and walnuts and stir to coat. If butter is refrigerated, microwave in 10-15 second intervals until very soft but not totally melted. Add butter and eggs to the dry ingredients and mix/fold with a wooden spoon until no loose flour remains. It will seem like not enough moisture - just keep folding, it will come together. The batter will be very thick. Do not overbeat. Spread evenly in the pan. Bake for 1 hour or until done. (I baked mine for 1 hour and 5 minutes, as the middle still seemed a bit soft). In all, my husband LOVED this recipe, but it was not my favorite. Next time I would definitely add some extra salt as the cake tasted a bit "flat" without it. In retrospect, I also MIGHT have accidentally added 2 teaspoons of cinnamon instead of one? Oops. It was too much cinnamon for me, but as I said, my husband loved it as it reminded him of carrot cake. Baking it for an hour at 325 seemed like way too long, but it did result in nicely caramelized edges (all that sugar). However, all the apples melted into the cake! So next time I would probably cut them a bit bigger. I did almost mince them in some cases.

So what did you guys think of this week's episode? Are you going to join me next Friday on Facebook? I hope to see you there! Thanks again to everyone who watched live and remember, if you have any burning food history questions, you can send them to me in advance, message The Food Historian on Facebook, or ask live during the broadcast. See you soon!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed