|

In throwing an Autumnal Tea Party (see yesterday's post!), I wanted a simple but impactful dessert. Apples are plentiful in New York in September, but plain apple crisp, while delicious, didn't feel quite special enough for a tea party. The British have a long tradition of gleaning from hedgerows in the fall. Hedgerows often have apple trees, sloes, blackcurrants, and blackberries in fall. Sloes and blackcurrants are hard to find here in the US, but blackberries seemed like the perfect accent to the American classic. This recipe is endlessly adaptable as the crumble topping is great with any kind of fruit. You do need quite a lot of fruit for a crumble, which makes it nice in that it feels a little lighter on the stomach than cake or pie. These sorts of desserts were common in areas where fruit was plentiful and sugar and butter weren't. Apple Blackberry Crumble RecipeI never sweeten the fruit for a crumble (similar to a crisp, but without rolled oats) unless it is a very sour fruit like rhubarb or fresh cranberries. This topping has quite a lot of sugar, which is what helps make it so crunchy and delicious, but you definitely do not need additional sugar in the fruit, especially when pairing with ice cream. You can substitute whole grain flour for part or all of this to good effect as well. If you prefer a crisp, use 1/2 cup of flour and 1 heaping cup of rolled oats. 8+ small apples (I used a mix of gingergold and gala) 1 pint (2 small packages) fresh blackberries 1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour (plus more for the fruit) 1 scant cup white sugar 1/2 cup coldish butter 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon pumpkin spice Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F. Peel the apples, cut into quarters, cut out the core, and slice. Wash the blackberries and drain. Toss the apples and blackberries with flour to coat (this will thicken the juices). Add to the baking dish. Then make the crumble. Mix the flour, sugar, salt, and pumpkin spice. Then cut the butter into small cubes, toss in the flour mix, and using your hands squeeze and rub it into the flour mix until it holds together when squeezed. Crumble gently over the fruit in an even mix, then bake for 40-50 minutes, or until the fruit is bubbly and thick and the crumble is golden brown. Serve warm with vanilla ice cream. There's nothing like a warm crisp with cold vanilla ice cream, and I think this is my new favorite kind. Blackberries and apples seem like a match made in heaven. What's your favorite autumnal dessert? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

I call this old-fashioned baked applesauce custard because while it's not from a historic recipe, it does hearken back to several styles of historic recipes. Its antecedents are:

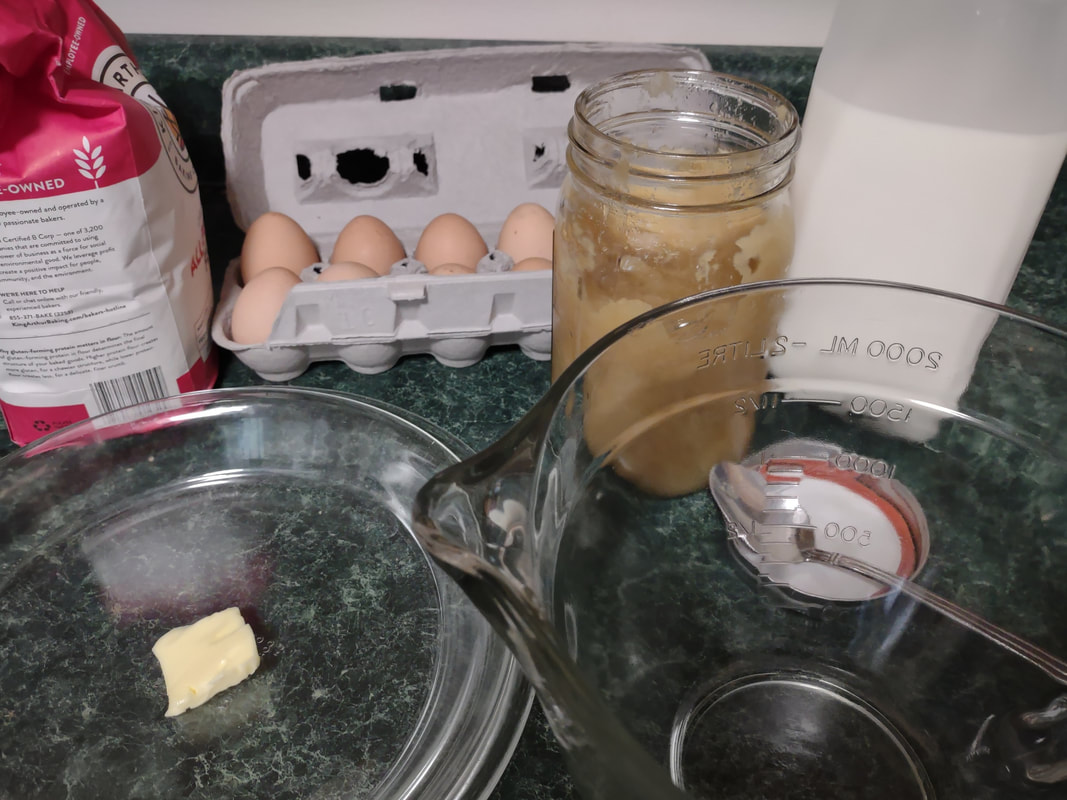

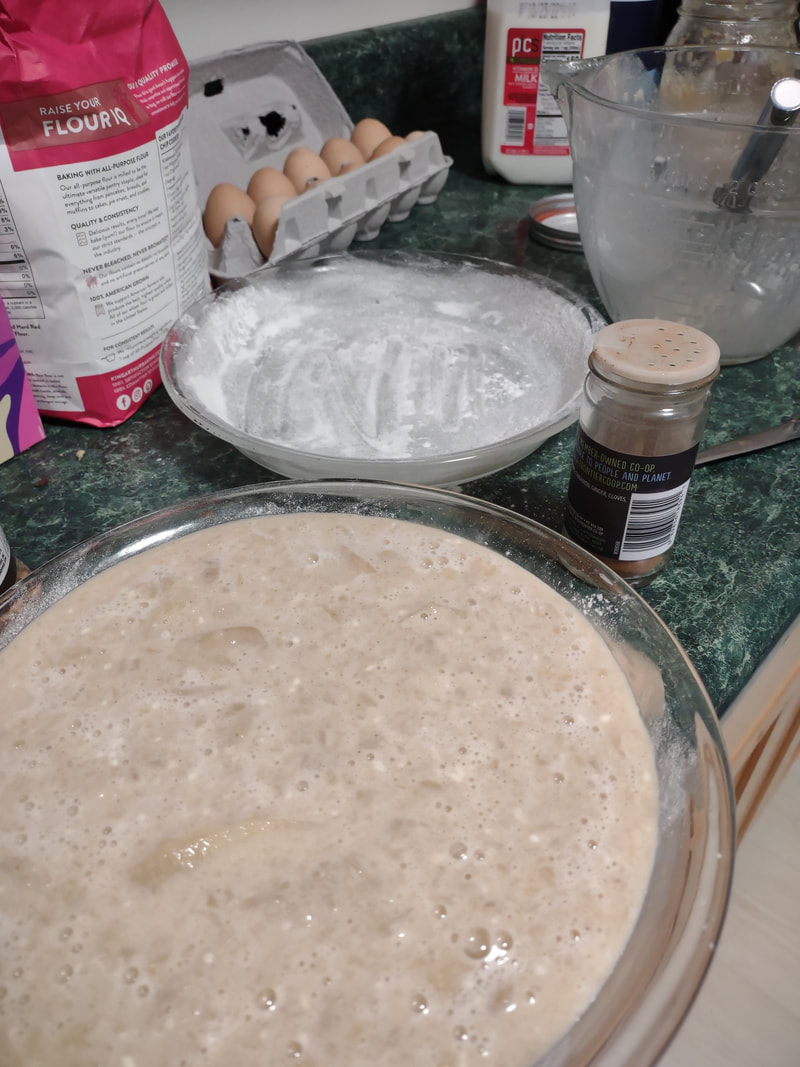

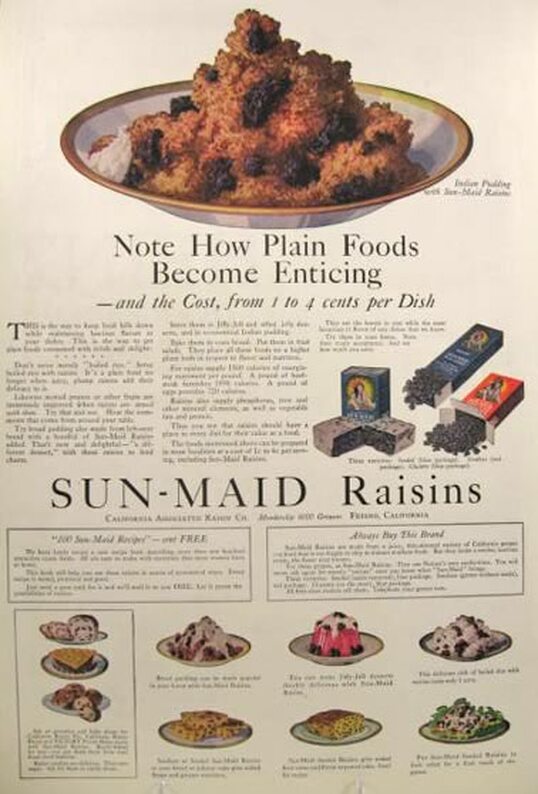

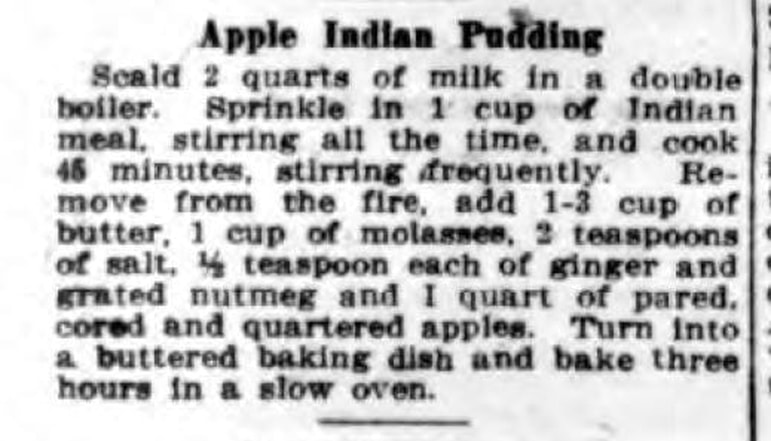

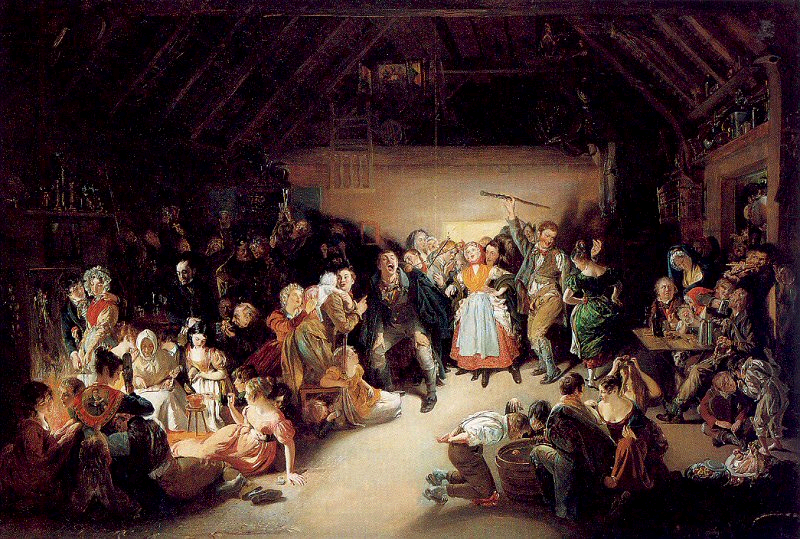

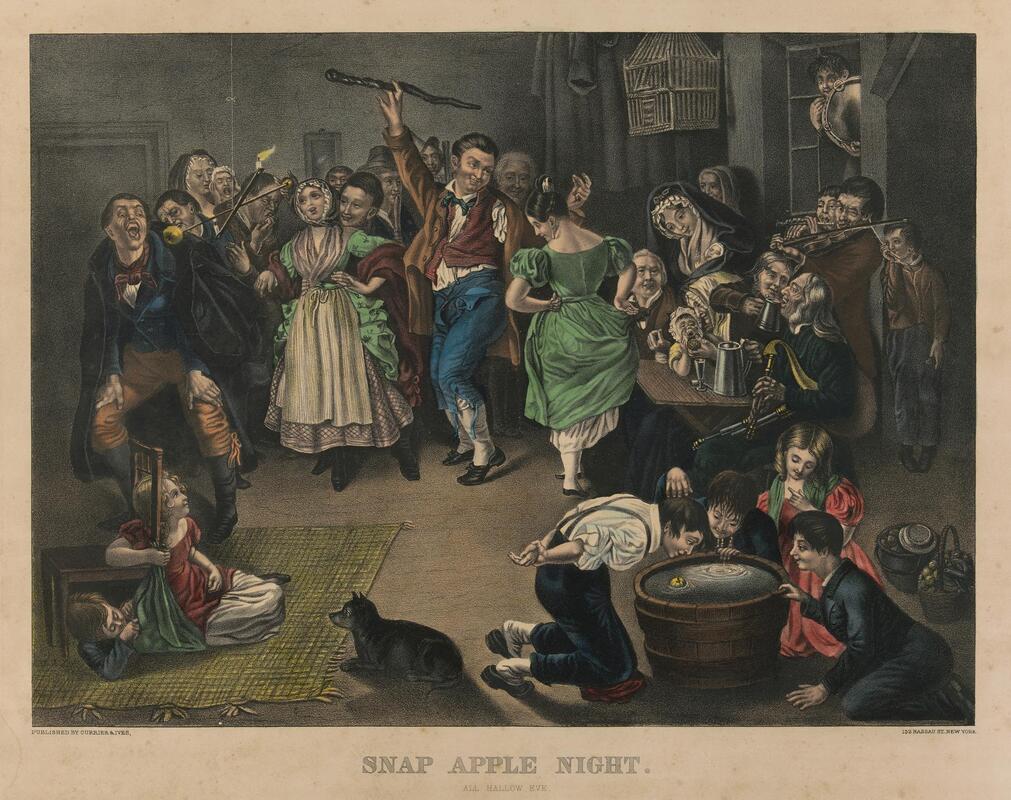

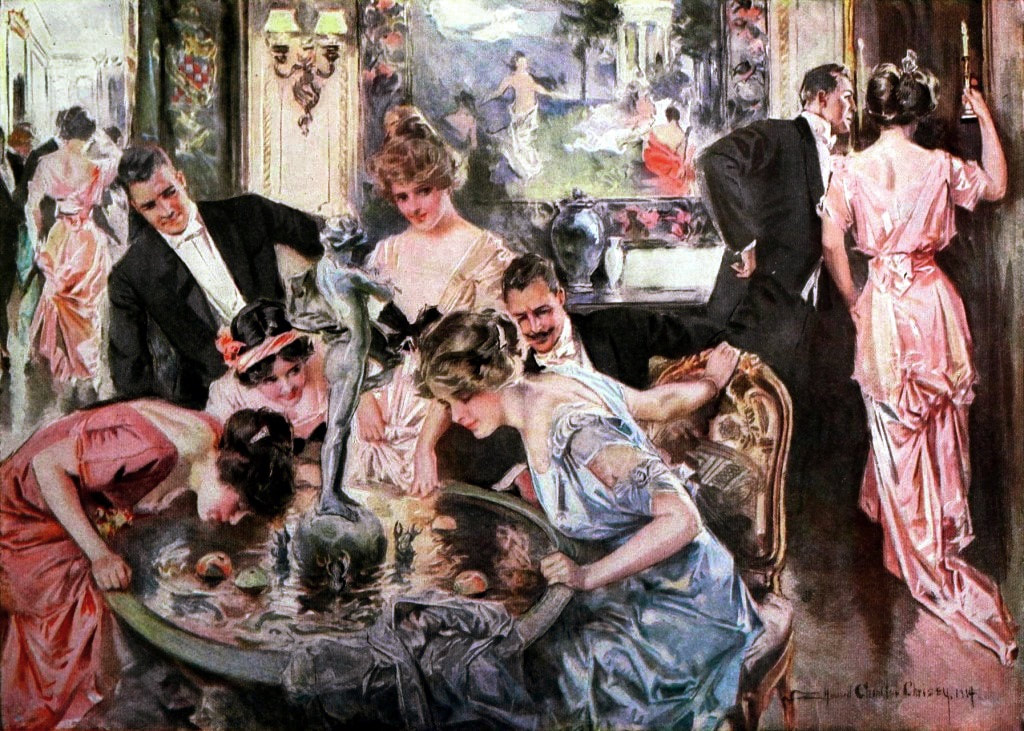

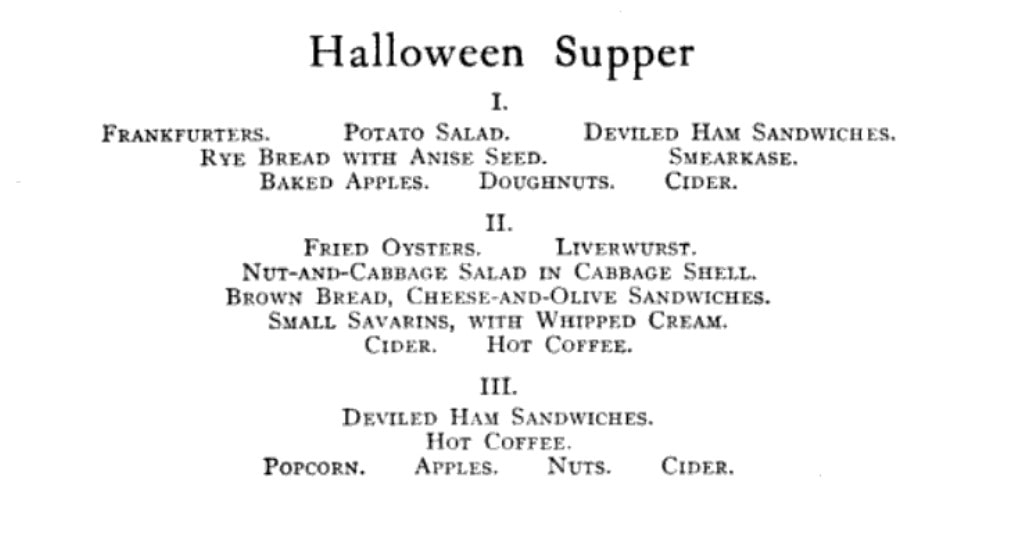

Apples plus dairy seem to be a recurring theme, and while apple crisp with ice cream and apple pie with whipped cream are a delight, I wanted to try something a little different. Enter, baked apple custard. As you may have noticed, I've been on an apple kick lately, and this custard just doesn't disappoint. I had most of a quart jar of homemade applesauce in my fridge that needed using up as I hadn't canned it, and it had been made over a week ago. If you leave applesauce in the fridge long enough, it will start to ferment! And I didn't want that work to go to waste. I also felt like cooking something a bit more dessert-y than just eating plain applesauce with a little maple syrup or cream. This recipe is a mash-up of two, mainly - an applesauce custard pie recipe, and crustless custards. It was an experiment that turned out eminently delightful. Old-Fashioned Baked Applesauce Custard RecipeThis recipe starts with a very simple applesauce recipe, although you can use unsweetened store-bought applesauce if you prefer. But I liked the chunky kind, like my mom used to make. Start with apples you like. Most modern dessert apples will not need sweetening. Peel them, quarter, and cut out the cores (I use a sharp paring knife to make a V-shape around the seeds, like my mom used to do). Slice them lengthwise into a pot and cook over medium-low heat, uncovered, stirring occasionally. If the apples seem dry, add two tablespoons of water to get them started. The bottom ones will cook into mush, and the ones closer to the top will stay firmer. If you prefer, you can mix cooking apples like McIntosh with a crisper apple like Honeycrisp or Gala to get the same result. I used a mixture of Gingergolds, Golden Supremes, and Winesaps - some of my favorite locally available apples. Once all the apples are fork-tender or sauce, et your applesauce cool fully, and you're ready to start the recipe. 2 eggs 1/3 cup sugar or maple syrup 1 tsp. cinnamon 1/4 teaspoon salt 2 tbsp. flour 1 cup milk 1 1/2 cups homemade, unsweetened applesauce Preheat the oven to 350 F. Grease a glass pie plate generously with butter, and flour it (sprinkle with flour and tap and rotate the pie plate to coat it with a thin layer of flour - discard any extra, or use it in the recipe). In a large bowl with a pouring spout, whisk the eggs, sugar, cinnamon, and salt together until well-combined. Add the flour and whisk well to prevent lumps. Then stir in milk and applesauce. Pour into the buttered and floured pie plate, and carefully place in the oven. Cook 30-40 minutes or until the center is set. The top will be sticky. Let it cool slightly and serve warm, or chill and serve cold. This recipe is easy to double, like I did, but the high applesauce ratio means it's very soft and delicious, but it won't cut up into a nice, neat pie slices (as you'll see below). Better to make it in a pretty oval baking dish and serve with a large spoon instead of in slices. It doesn't need it, but add some whipped cream if you're so inclined. Old-Fashioned Baked Applesauce Custard is simple and homey, creamy and delicious whether served warm or cold. It tastes of fall and childhood, and that particular poignant longing for a past or place you know never existed that seems so endemic to autumn. It's the perfect dish for that transition between fall and winter, when November gets misty and the blazing leaves turn brown, and the days get darker. Who needs the fuss of pie crust? It makes a perfect after-school snack, weekend breakfast, or comforting dessert after a long work day. It doesn't look like much, but you could gussie it up for Thanksgiving too, if you've a mind. And while it's almost certainly better with homemade sauce, it's probably pretty darned good with the store-bought kind, too. Happy eating, friends. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! I don't remember when I first encountered "Indian pudding." Derived from the Colonial name for cornmeal - "Indian meal" - it's an iconic dish of New England, though it isn't often made anymore. Combining Indigenous foodways, European cooking techniques, and molasses, a ubiquitous sweetener made cheap by the brutal labor of enslaved Africans, Indian pudding reflected the kind of stick-to-your-ribs cooking common in the Colonial period when people ate less frequently and engaged in harder labor, and with less access to heating than they do today. The above advertisement by Sun-maid Raisins from 1918 is a good illustration of this. "Note How Plain Foods Become Enticing," the ad reads, showing how Indian Pudding could be spiced up with raisins, and then goes on to show just how inexpensive raisins were. Historically, raisins were rather expensive, and had to be stoned (remove the seeds) by hand, a labor-intensive step that continued until the early 20th century. By the time Sun-maid is advertising in 1918, you no longer had to stone raisins - they came seedless. Clearly Sun-maid was trying to convince people that raisins were a more economical purchase than previously believed. Also, the use of Indian Pudding to illustrate the "plain foods" shows how it was viewed by most Americans at that time - plain, cheap, and filling. Indian pudding also fit nicely into rationing suggestions to use less sugar, refined white flour, and fats. With its ingredients of cornmeal and molasses, Indian pudding fit the bill. I first ran across a recipe for Apple Indian Pudding when researching the history of the Farm Cadets in New York State. The article right next to it was about the establishment of the Farm Cadet Corps under the State Military Training commission. Published in the Buffalo Evening News on April 19, 1917, just two weeks after the United States entered the war, it was included as part of a column called "Lucy Lincoln's Talks" and was one of many recipes. Although the United States Food Administration was not yet formed and no rationing recommendations had been issued, President Wilson had been publicly discussing the role of food in the war effort. Throughout the First World War, the United States Food Administration and home economists hearkened back to the Colonial period for several reasons. First, it appealed to Americans' sense of patriotism. Following the American Civil War, Northern reformers made a concerted effort to re-unite the nation and define what it meant to be American. Thanks to the unconscious bias of white supremacy, that idea became closely connected to New England and the mythology around the Pilgrims and the founding of the nation (despite the fact that Spanish Florida, Virginia, parts of Canada, and even New York had been settled earlier). Second, hearkening back to the Colonial period allowed ration supporters to encourage the substitution of non-rationed food items like cornmeal and molasses which had deep Colonial roots, for rationed foods like refined white flour and refined white sugar, which were needed for the war effort. Third, these ingredients were often very inexpensive. By connecting them to the honored founders of the country, food reformers could convince middle and upper class people to eat what may have been previously only associated with the poor and working class, in the name of patriotism. Despite the lack of actual rationing recommendations at this point, the recipe for Apple Indian Pudding would have fit very nicely into the requirements. It used cornmeal, which saved wheat. It used molasses and apples for sweetener, which saved sugar. It used two quarts of milk, which would help use up the milk surplus and add protein. It was also extremely inexpensive and filling, which meant it had appeal for folks on a budget or with large families. The recipe does, however, call for 1/3 cup of butter, which would become one of the recommended ration items in just a few months. Apple Indian Pudding RecipeI have made Indian Pudding before for a talk, and it's lovelier than you'd think. Here's the original recipe: "Scald 2 quarts of milk in a double boiler. Sprinkle in 1 cup of Indian meal, stirring all the time, and cook 45 minutes, stirring frequently. Remove from the fire, add 1/3 cup of butter, 1 cup of molasses, 2 teaspoons of salt, 1/2 teaspoon each of ginger and grated nutmeg, and 1 quart of pared, cored, and quartered apples. Turn into a buttered baking dish and bake three hours in a slow oven." And here's a modern translation: 8 cups (or a half gallon) whole milk 1 cup cornmeal 1/3 cup butter 1 cup molasses 2 teaspoons salt 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon grated fresh nutmeg 3-4 apples Preheat the oven to 300 F. In a double boiler or heavy-bottomed pot, heat the milk, but do not boil. Once hot, slowly whisk in the cornmeal and cook, stirring frequently, for 30-45 mins or until the cornmeal is fully cooked and has absorbed the milk. Remove from heat and while hot, stir in the butter, molasses, salt, and spices. Peel, core, and slice the apples thickly. Stir the apple slices into the cornmeal mixture, and tip it all into a buttered glass or ceramic baking dish. Place in the oven and let bake for 3 hours, uncovered. Serve hot or warm plain (ration-friendly) or with vanilla ice cream or unsweetened liquid cream (not-so ration-friendly). Although the original recipe calls for quartered apples, most modern apples are very large, and a quarter might be too big, which is why I suggest slicing them instead. If you're in an area of the world that gets cold in the fall and winter, Apple Indian Pudding is the perfect, homey dessert to attempt on a day when you'll be puttering around the kitchen or the house all day. Pop some baked beans in with it if you really want a traditional New England supper (and a ration-friendly one!). It really does take three whole hours to bake (other versions included steaming like plum pudding), but the long, slow heat turns the normally crunchy cornmeal into melting softness. There's a reason why it's still so popular in New England. If you want to know more about the history of Indian Pudding, including how to make a historic recipe, check out my lecture below! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Happy Halloween, everyone! When it comes to Halloween, pumpkins get all the love. But Halloween's REAL favorite fruit is apples. Let me explain. The origins of Halloween date back to ancient Ireland and Scotland - a place where the now-ubiquitous pumpkin was not available until the 16th century at the earliest, and not really in practice until the 19th century. But apples? Apples were everywhere. They were the best fruit for storing over the long winters. Certain varieties kept better than others, but unlike soft berries or less sweet root vegetables, apples were a reliable source of sugar at a time when calories were all-important. 19th and early 20th century historians often attributed the apple celebrations of the British Isles to Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit orchards, including apples, which in Romance languages share the Latin root word "pomum," meaning fruit. "Apple" was also originally meant to describe all kinds of fruits, not just the Malus domestica, much like "corn" historically referred to all types of grain (and which is why most of the rest of the world refers to it as "maize.") I'm skeptical of the direct connection to Pomona. More likely was simply the fact that apples were in season at this time of year. Apple harvest generally lasts from August through the end of October, depending on the breadth of your apple varieties. Apples were eaten fresh, put up as sauce or apple butter, dried, and processed into apple cider, hard cider, scrumpy, applejack, and apple cider vinegar. But for Halloween, fresh apples were still very common, and a LOT of Halloween traditions involve fresh apples. Snap Apple NightIn Ireland, Halloween was often referred to as "Snap Apple Night," as is illustrated by the classic painting above by Irish artist Daniel Maclise. Maclise based it on a real Halloween party he visited in Ireland in 1832. He illustrates many of the classic traditions. At left, a courting couple burns nuts on the hearth grate to see how their relationship will fare and girls drip molten lead into water to read their fates in the shapes. At right, boys bob for apples and others play pranks on the musicians. And the center, namesake of the painting, is snap apple - a rather precarious and hilarious game. A pair of wooden sticks are fastened together into a cross. On two opposing ends, the sticks were sharpened and apples stuck on. On the opposite ends, burning candles were affixed. The whole thing was hung from the ceiling on a string, and set spinning. The goal was to catch and remove the apple using only your mouth - no hands allowed - without getting hit in the face by a burning candle, or the hot wax. Upon exhibition, Maclise's painting was accompanied by the following poem: There Peggy was dancing with Dan While Maureen the lead was melting, To prove how their fortunes ran With the Cards could Nancy dealt in; There was Kate, and her sweet-heart Will, In nuts their true-love burning, And poor Norah, though smiling still She'd missed the snap-apple turning. As Irish immigrants came to the United States following the great potato famine of the 1840s, they brought their Halloween traditions with them. This rather poorly rendered lithograph by Currier & Ives is a copy of a copy of Daniel Maclise's original painting. Printed in 1853, it reflected the adoption of Halloween by Americans. Missing the divination happening hearthside, this lithograph focuses on the game of snap apple, the dancing and music, and in the foreground, bobbing for apples. This image from the frontispiece of The Book of Hallowe'en, published in 1919 by Ruth E. Kelley, shows the staying power of Maclise's painting, and the power of the mysterious history of Halloween. In this illustration, ("from an Old English print"), we have bobbing for apples and a well-lit game of snap apple. The clothing of the people in the illustration evokes somewhere between the turn of the 19th century and the 1840s - the fuzziness of the time period part of the mystique of the book, which purports to trace the history of Halloween and yes, does link it to the Roman festivals for Pomona. Kelley's book was part of a resurgence of interest in Halloween throughout the United states, and one of a number of books published on the subject, including more serious histories like hers, and more commercial publications like Dennison's Bogie Books. Snap apple remained a popular game, although later versions were slightly safer. As the century wore on and we turned to the 20th century, alternatives went from attaching the apples with strings, to replacing the candles with small sacks of flour (far less dangerous than flame and hot wax, but no less humiliating to get hit in the face with a puff of flour), and eventually simply hanging apples from a string. An even easier later variation even replaced the apples with donuts! As Halloween traditions shifted from at home parties to public events like costume parades and community trick or treating, snap apple faded into obscurity. History of Bobbing for ApplesThe above painting is one of my favorites from the time period. Howard Christy's "Halloween" depicts a very fancy Progressive Era Halloween party that still smacks of the Gilded Age. The decadent mansion, with enormous Classical paintings, gilded furniture, and elaborate gaslights is filled with men in tuxedoes and sleek haircuts and women in glistening silks and satins - nary a fancy dress costume in sight. In the foreground a fancy Classical style fountain has a few apples floating in it, and one young lady bends close - contemplating bobbing, perchance? - while others look on. In the background, a young woman and a man gaze into a mirror - the woman holds a lit taper candle, which evokes the Halloween divination tradition of gazing into a dark mirror by candlelight at midnight. Supposedly your future husband would appear. It's a slightly ridiculous take on the historically very messy and hilarious tradition of bobbing for apples. Like snap apple, bobbing for apples (sometimes known as dunking or ducking for apples), was a game of hilarity, skill, and danger. A large basin - often the wooden laundry basin - was filled with water and apples floated on top. The object of the game was to retrieve them with only your mouth - hands behind your back. There were a number of tricks to retrieve them. Some tried to grab the stem in their teeth. Others used their lips to suction the side of the apple. Still others shoved their entire heads under water, trying to trap the apple between their mouth and the bottom of the basin. Like with snap apple, courting couples could cooperate to sandwich an apple between them. And like snap apple, bobbing for apples drifted into obscurity as the 20th century wore on, although it remained more firmly in the American cultural consciousness than snap apple.  This undated postcard, likely from the turn of the 20th century, features two girls and a boy bobbing for apples. It's one of the few images of the period showing a girl actually doing the bobbing while the other two watch. A smoking jack o'lantern typical of the period sits in the foreground. Toronto Public Library collection. Apple Divination In this 1909 Halloween postcard by illustrator Bernhardt Wall, a young woman is tossing a long apple peel over her shoulder, believing that the peel will fall to the floor in the shape of a letter that will reveal the first letter of her future husband's name. Posted by collector Alan Mays to Flickr. Like May Day and Midsummer, Halloween was chock full of divination opportunities, and apples were at the center of several. The more famous is apple peel divination. A young girl would peel an apple in a long strand - sources vary over whether she had to do the whole apple in one unbroken peel - and toss the peel over her shoulder. Supposedly, the peel would land in the shape of the initial of the man she was to marry. In practice it seems like there would be a lot of S's, C's, L's, and O's, and not too many T's or H's. Another romantic divination game involved the apple seeds. Pressing fresh seeds to your forehead you would assign to each one a crush or romantic interest. The one that stayed on the longest was destined to be yours. Still other apple seed games involved squeezing them in your fingers. The direction they shot out of your fingers was where your true love would approach from. Candy and Caramel Apple HistoryAlthough apples were consumed regularly in the autumn months in northern climes all over the world, it wasn't until the late 19th century that the modern apple as we know it today developed. Starting post-Civil War, fruit orchardists like the Stark Brothers and agricultural college experimental stations began developing specific varieties of fruit, grafted for taste, disease resistance, ripening time, etc. With these scientific developments came the emergence of the modern dessert apple. Designed for eating, rather than for producing cider, these apples were sweeter than their predecessors. Apples, through improvements in orchard husbandry, were also getting larger, more standardized, and shipped better. People in cities were able to access fresh apples on an increasing basis. Which led to innovations in eating. Candying fruits in sugar or honey syrup is ancient. But the idea of dipping fresh apples in a candy coating was relatively new. Candy apples are coated in a shiny red candy glaze, whereas caramel apples are dipped in sticky brown caramel. Taffy apples are somewhere in between. Toffee apples, as they are called in England, are similar to both. Although candy apples are widely attributed to William Kolb of New Jersey in 1908, but toffee apples and caramel apples have newspaper references in England and France in the 1890s. Also in 1908, one newspaper article for "Caramel Apples" went viral - appearing in 62 newspapers across the country. It is not quite the same as the caramel apples we associate with today, which are more similar to British toffee apples of a sour apple dipped in soft caramel. These were more like a combination of the medieval candied apples and modern caramel apples, with nary a stick in sight. Here's the article in its entirety: CARAMEL APPLES ARE GOOD. As you can see from the recipe, these apples must have been incredibly sweet as they were both cooked in syrup and then also covered in caramel and more syrup and served with whipped cream. No wonder the sugar addicts of 1908 made this recipe go viral! Caramel and candy apple associations with Halloween come a bit later, coinciding with the apple harvest season. Most Americans connect them to county fairs and old-fashioned trick-or-treating, when people still made homemade treats to distribute before the candy scares of the 1970s. Today, they're found everywhere from pick-your-own apple orchards to places like Coldstone Creamery, although most are now dipped in chocolate, rather than caramel or candy, as getting a candied coating that is thick enough to stick and soft enough not to break your teeth is a bit of a lost art. Chocolate is far easier to handle. Apple Cider For Halloween MenusAlthough the Pumpkin Spice latte may have taken over fall in today's world, in my opinion apple cider is a much better companion. And historic cooks and party planners agreed. Apple cider was often featured in Halloween menus like the ones above from the late Victorian period on. This would have been sweet cider, of course, because even before Prohibition most home economists and domestic scientists were advocates of the Temperance movement. Whether served cold or spiced, cider was often associated with other more casual foods like doughnuts, popcorn, frankfurters (aka hotdogs), pickles, and nuts. Outdoor events like bonfires, hay rides, and outdoor parties along with public events where children or teenagers were present were also commonly associated with simpler foods like outlined in the menus above. The prevalence of cider reveals its more industrial origins. Apple orchards growing dessert apples were more prevalent, as older heirloom cider apples fell out of use. Commercial bottling in the mid-19th century allowed companies like Martinelli's to produce hard cider and sodas. The growing popularity of the Temperance movement shifted companies away from hard cider and toward unfermented sweet cider, which remains the focus of Martinelli's today. Companies like Mott's also started out making hard cider, and then shifted to sweet in the 20th century as bottling sanitation improved and the demand for non-alcoholic beverages increased. Today, most commercially-sold apple juice is filtered and pasteurized, making for a thinner-bodied, sweeter, and less acidic product. Apple cider is generally not filtered and is sometimes sold unpasteurized, as the acidity level gives it anti-microbial properties. This, along with the sugar content, is generally also what allows apple cider to ferment, rather than spoil. Today, most hard cider is inoculated with champagne yeast, but historically wild yeast would naturally gather in the sugary liquid. Sweet cider is available most places where apples are grown, and New York is the second-largest apple-producing state in the country, so I'm lucky to have ample access to it. I've even made my own with a historic cider press! (Just a small, household sized one, not one of the giant presses.) In all, apples take the cake (sometimes literally) in Halloween eats in large part because they were a readily available source of sugar a time when refined cane sugar was largely the purview of the wealthy. And besides which, although pumpkin pie was also associated with Halloween, there's only so much of it you can eat before you get sick of it. Apples - whether candied and carameled or turned into pie, salads, cakes, muffins, crisps, dumplings, sauce, butter, cider, or even candy - are tough to get sick of, especially after a long, hot summer. What do you thing - do apples beat out pumpkins for ideal Halloween eats? Or should we be celebrating other fruits altogether, like pears or blackberries? Edwardian HalloweenAs I was working on this post, I was watching BBC's Edwardian Farm (which is also available on Amazon Prime - using the link helps support The Food Historian). Episode 2 is great to watch in its entirety (lime burning, apple cider pressing, and egg preservation, oh my!), but I've started the YouTube video below at the beginning of the Halloween party, where you'll see a variation of snap apple, an apple divination game involving sticking apple seeds to your forehead, and of course, fermented apple cider. Enjoy, and have a happy, apple-ish Halloween! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

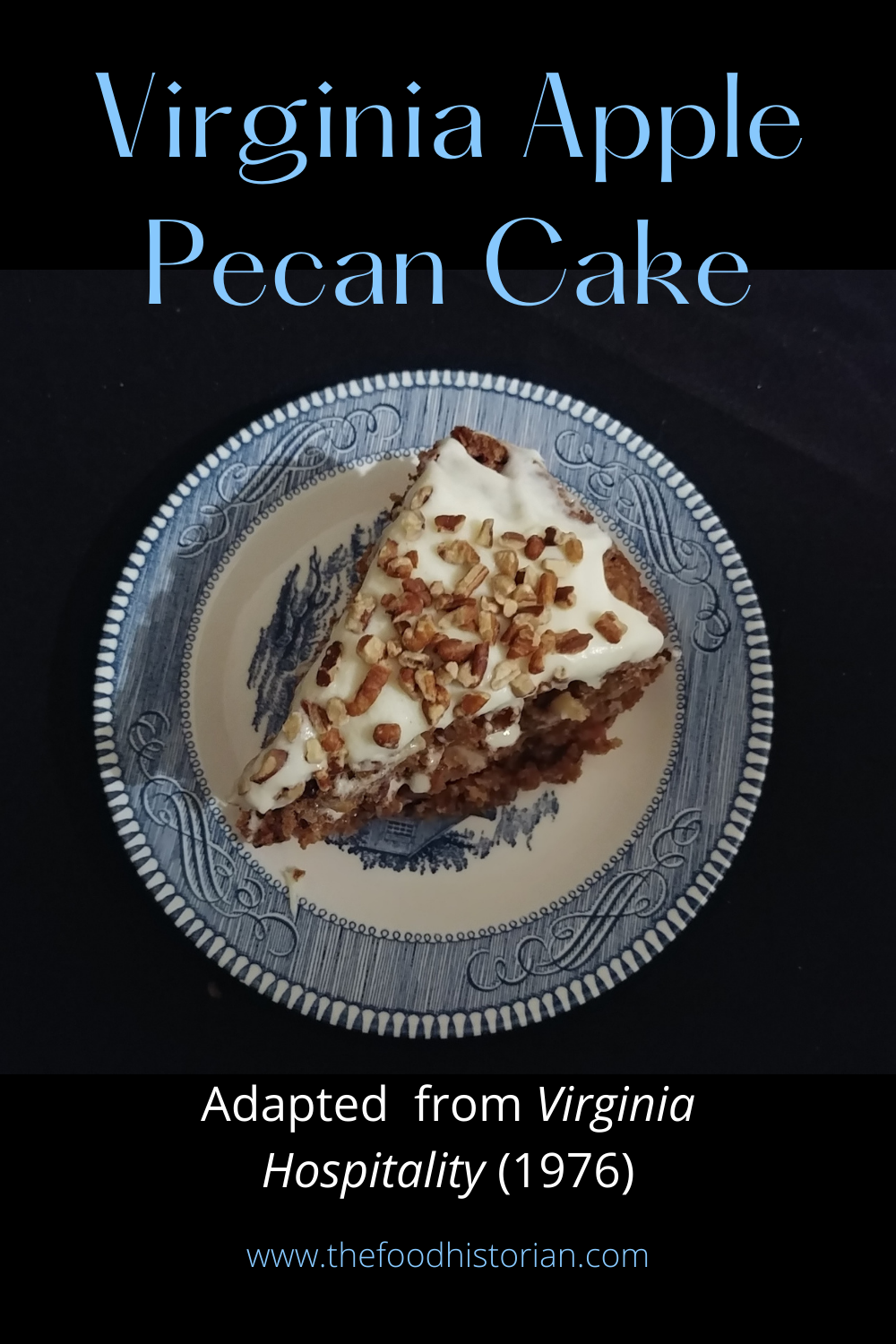

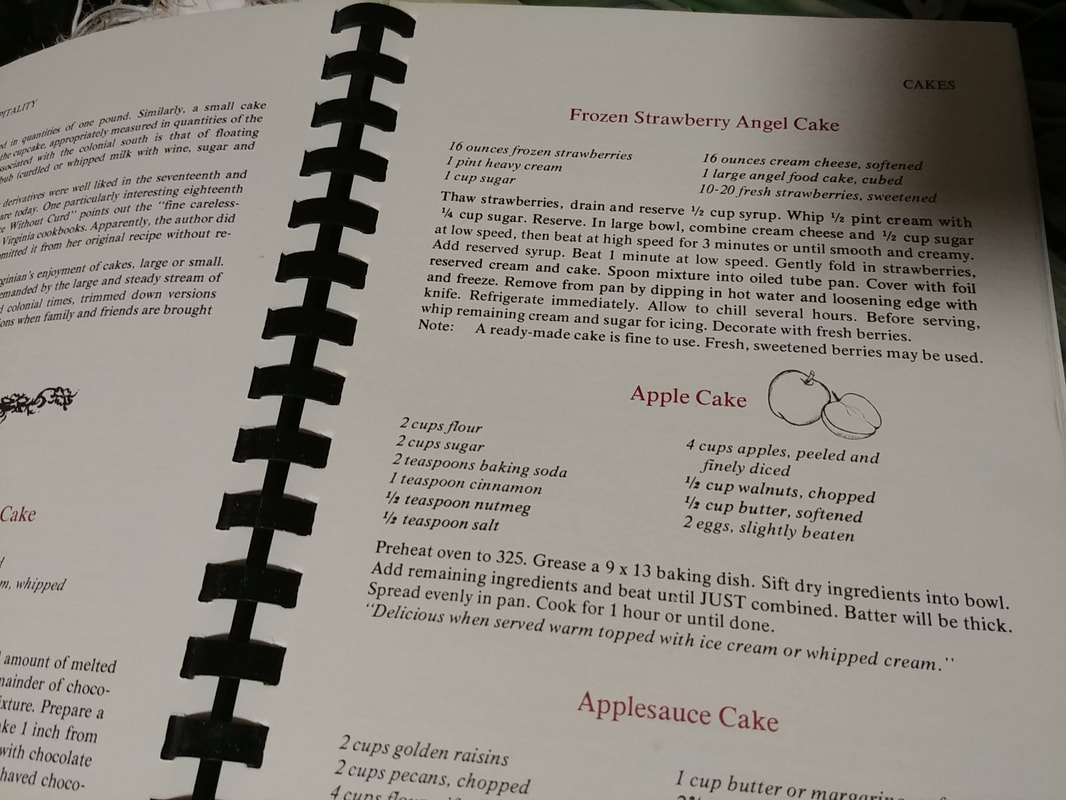

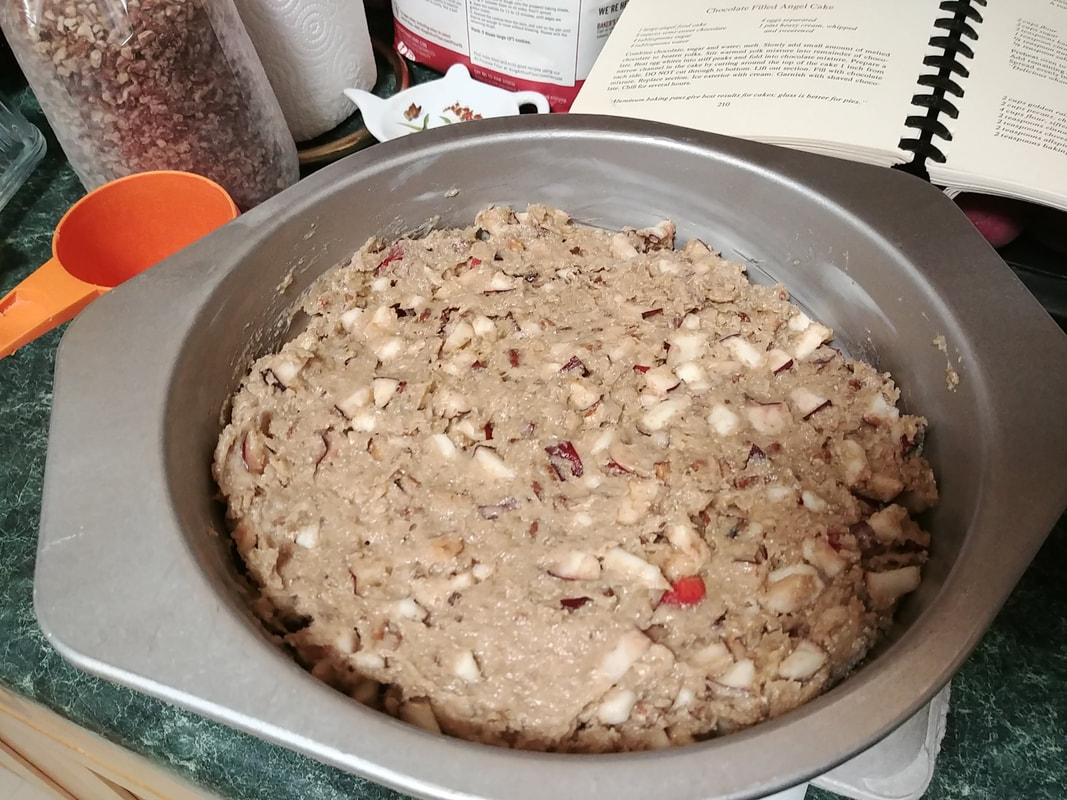

Here we are, five days later, and we finally have an election result. I made this cake on election day because I didn't have yeast for "real" election cake (more on that below), I had a bunch of homegrown Liberty apples to use up, and felt like making a layer cake with my new cake pans (somehow I lost one of my old pair of cake pans?). I had made this Virginian Apple Cake before, but it didn't turn out too great. So I tried again and did some tweaking and this time it turned out WONDERFULLY. It's now officially Virginia Apple Pecan Cake, in my book. Virginia Apple Pecan CakeThis recipe is from the community cookbook, Virginia Hospitality, first published in 1976 for the Bicentennial, but my copy is the ninth printing, from 1984. It's a fascinating little recipe - the only liquid comes from the eggs and softened butter and the apples themselves. The batter is VERY thick, but bakes up beautifully - a light and somewhat fragile texture - essentially just apples and nuts held loosely together by a light spiced batter. Here's the original recipe: The original recipe reads: 2 cups flour 2 cups sugar 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg 1/2 teaspoon salt 4 cups apples, peeled & finely diced 1/2 cup walnuts, chopped 1/2 cup butter, softened 2 eggs, slightly beaten Preheat oven to 325. Grease a 9 x 13 baking pan. Sift dry ingredients into a bowl. Add remaining ingredients and beat until JUST combined. Batter will be thick. Spread evenly in pan. Cook for 1 hour or until done. "Delicious when served warm topped with ice cream or whipped cream." It certainly is perfectly lovely as a plain sheet cake, but I wanted something a little different, so I made some changes not only to the style but the recipe itself. Here's my recipe: 2 cups flour (I used 1 cup all-purpose, 1 cup whole grain rye) 1 1/2 cups sugar 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg (or thereabouts) 1/2 teaspoon salt at least 4 cups apples, finely diced 1 cup chopped pecans 1/2 cup butter, softened 2 eggs, slightly beaten Preheat oven to 325 F and grease two 9 inch round cake pans. Add all dry ingredients to a large bowl and whisk to combine. Add chopped pecans and whisk to combine. Take 4-6 freshly washed Liberty apples (they will be small) - slice into thin slices and then cut crosswise to make fine dice. You can leave the skin on. Fill at least 4 cups of apples and add to dry ingredients, then cut up the rest of the apple you were slicing and add to the bowl. In a small separate bowl, melt the stick of butter slightly in the microwave (10-20 seconds) and add to the big bowl. Add 2 eggs and with a wooden spoon combine all, stirring and folding until no loose flour is left. Divide into two pans and bake 45-60 minutes or until the cake springs back in the center to the touch. Cool on a rack. Salted Caramel (or Maple) Buttercream FrostingI happened to have some Monin Salted Caramel Syrup laying around the house, but if I make this again I'll probably use maple syrup and some salt. The salty-sweet frosting makes a nice (but rich) contrast to the not-as-sweet cake. 1 stick salted butter, softened 2 tablespoons to 1/4 cup syrup powdered sugar salt With a fork, beat the syrup into the softened butter. Add enough powdered sugar to make a thick frosting. Taste and add salt a few grains at a time, tasting between each addition. When the cakes are cool, frost one layer, then top with the other, and frost the top. This won't be enough to frost the whole cake, just the layers. Sprinkle more chopped pecans on top for decoration. A Brief History of Election CakeElection Cake is a democratic tradition that dates back to the earliest days of our Republic, even before we were officially our own country. Puritans in New England celebrated it in the 17th century, but was important throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Election Day was once held in the spring, but in 1845 Election Day was codified to be held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Back when only propertied free white men were allowed to vote, election cake was nonetheless part of community celebrations around election day. and the similar Muster Day, a celebration from the Muster Act of 1792, which called every able-bodied man aged 18 to 45 to muster for the local militia. Generally held in September and largely in effect until after the Civil War, Muster Day often required the bribe of alcohol, and communities would often have county-fair type celebrations as well. Like Muster Day, Election Day was a community affair, and that necessitated some publicly accessible food. Election Cake is in the tradition of Medieval English great cakes - expensive and enormous confections of fine flour, sugar, expensive imported dried fruits, spices, and nuts and soaked with wine or alcohol. The New England tradition was nearly identical, only the ingredients were much less expensive by that point. Like many old-fashioned cakes, Election cake is not leavened with baking soda or baking powder - it's leavened with yeast, generally homemade yeast like potato yeast. And because it is meant to serve a crowd, the proportions are enormous. The flour and sugar are measured in pounds, as many as a dozen. The generally accepted first published recipe of Hartford Election Cake comes from Amelia Simmons' American Cookery, first published in 1796 in Hartford, CT (another run was printed in Albany, NY also in 1796). Which makes me wonder if Hartford Election Cake wasn't an homage to the state in which it was published. Election Cake began to wane in popularity as the 19th century wore on, in part thanks to developments in cake baking technology, including the development of chemical leaveners like baking soda and baking powder. But in 1889, Ellen Wadsworth Johnson published a cookbook entitled, Hartford Election Cake and Other Recipes. Notable for its inclusion of ELEVEN separate recipes for Election Cake, the cookbook is nonetheless full of more conventional recipes. The title may have something to do with the fact that it was published in Hartford, Connecticut, despite the fact that it was written as a benefit for a church in New Hampshire. In her introduction, Ellen Wadsworth Johnson notes that most of the recipes come from "manuscript sources," indicating that even in 1889 it may have been a historical document. Maybe next year I'll have the time and energy to tackle a real election cake recipe, but for the meantime, Virginia Apple Pecan Cake will have to make a good substitute, and one you can eat any time of year. Did you make an election cake this year? Election Cake Resources

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

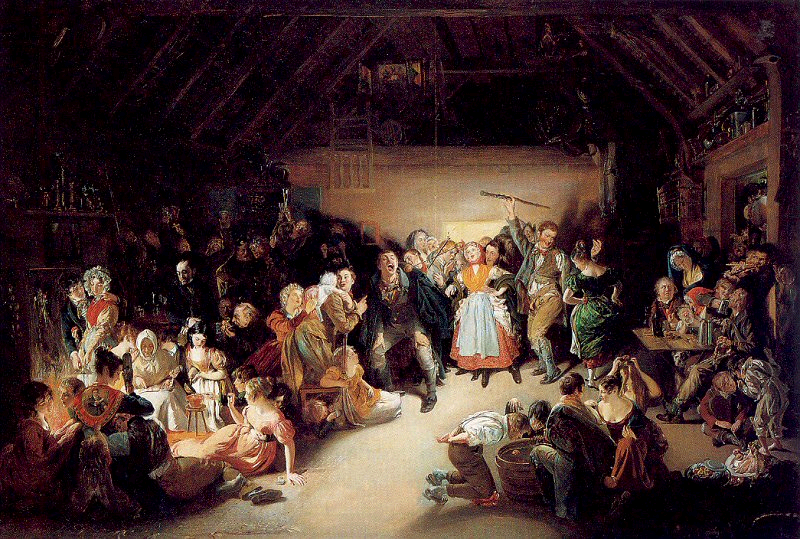

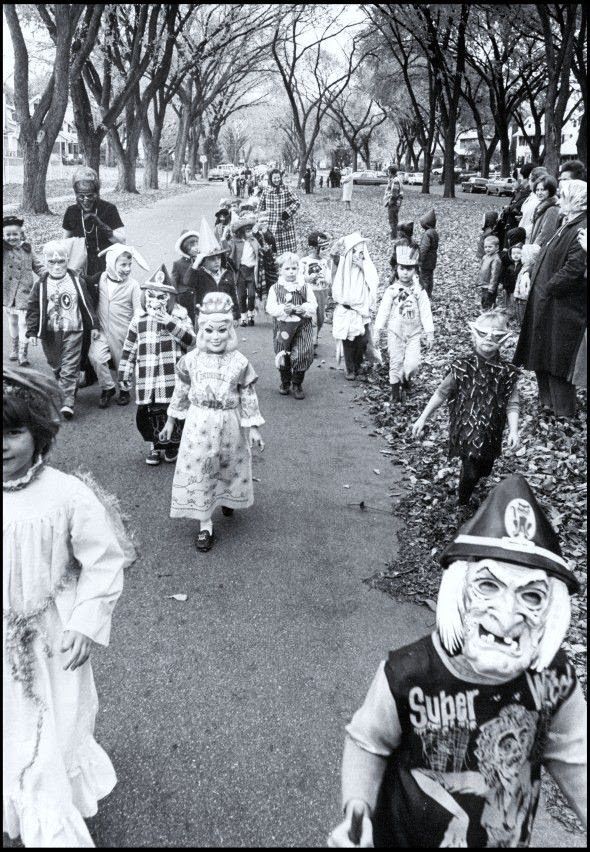

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 22 of the Food History Happy Hour! This was a very special Halloween themed episode! We made the early 19th century Stone Fence cocktail, and talked about all sorts of historic Halloween traditions and foods, including the Celtic and Catholic origins of Halloween, Halloween games and divination, including Snap Apple (as illustrated above), donuts, party foods including gingerbread, grapes and grape juice, apples, pumpkins, color themed parties, decorations, including Dennison's Bogie Books, the history of trick-or-treating, and more!

Stone Fence Cocktail (19th Century - 1946)

There's all kinds of versions of this - I was first introduced to the Stone Fence in the Roving Bartender (1946), and of course it's in Jerry Thomas' "How to Make Mixed Drinks" (1862) also has a version, which is largely how it gets popularized in bars across the country. But mixing hard cider with brown liquor dates to much earlier, and the type of brown liquor depends on the region. Both of these recipes call for Whiskey/Bourbon, but I decided to go with spiced rum. Other versions also call for Angostura bitters or cinnamon, which is unnecessary if you use spiced rum, like I did.

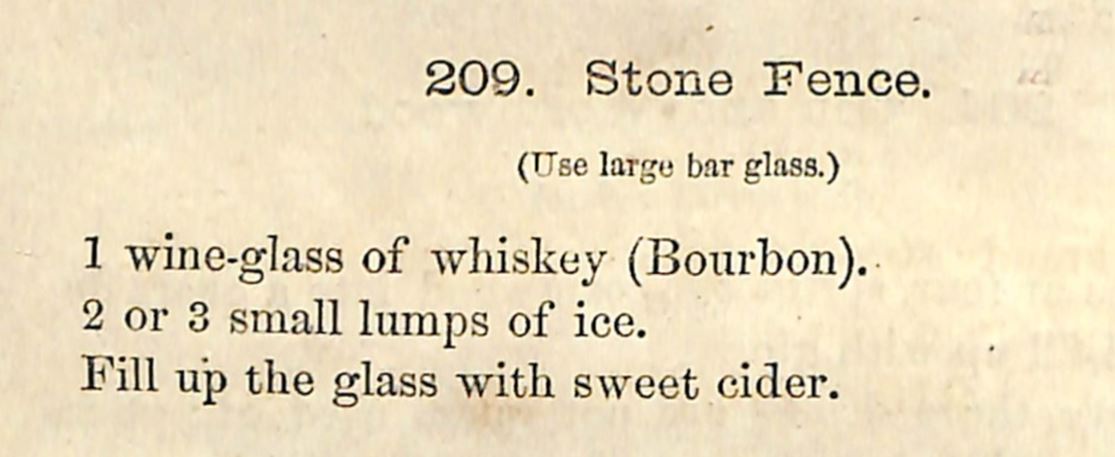

You'll note that the Jerry Thomas recipe actually calls for the use of sweet cider, which is unusual. Here's the original recipe:

(209) Stone Fence. (use a large bar glass) 1 wine glass of whickey (bourbon). 2 or 3 small lumps of ice. Fill up the glass with sweet cider.

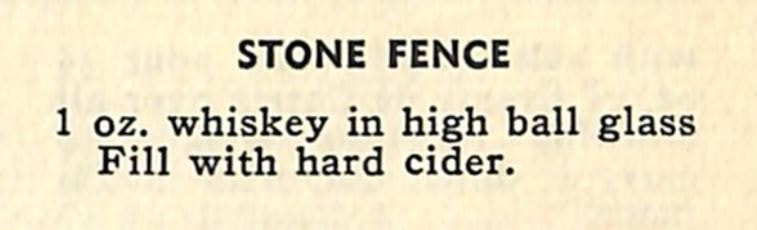

I like the Bill Kelly recipe from the Roving Bartender a bit better. Here's the original:

Stone Fence. 1 oz. whiskey in a high ball glass Fill with hard cider. And of course, there's my own version! 1 oz. spiced rum Fill with hard cider (I used Strongbow Artisanal Blend) I did not use ice, because I was lazy, but if you don't make sure your hard cider is chilled for the best version. You could also turn this into a sort of flip by heating the hard cider (don't boil unless you want to lose the fizz and the alcohol content) and adding the spiced rum at the last minute. Episode Links

I love Halloween and had a bunch of fun putting this together.

That's all for tonight! I hope everyone has a very Happy Halloween tomorrow and we'll see you in November for the next episode of Food History Happy Hour!

Food History Happy Hour is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail (like the Halloween packet) from time to time!

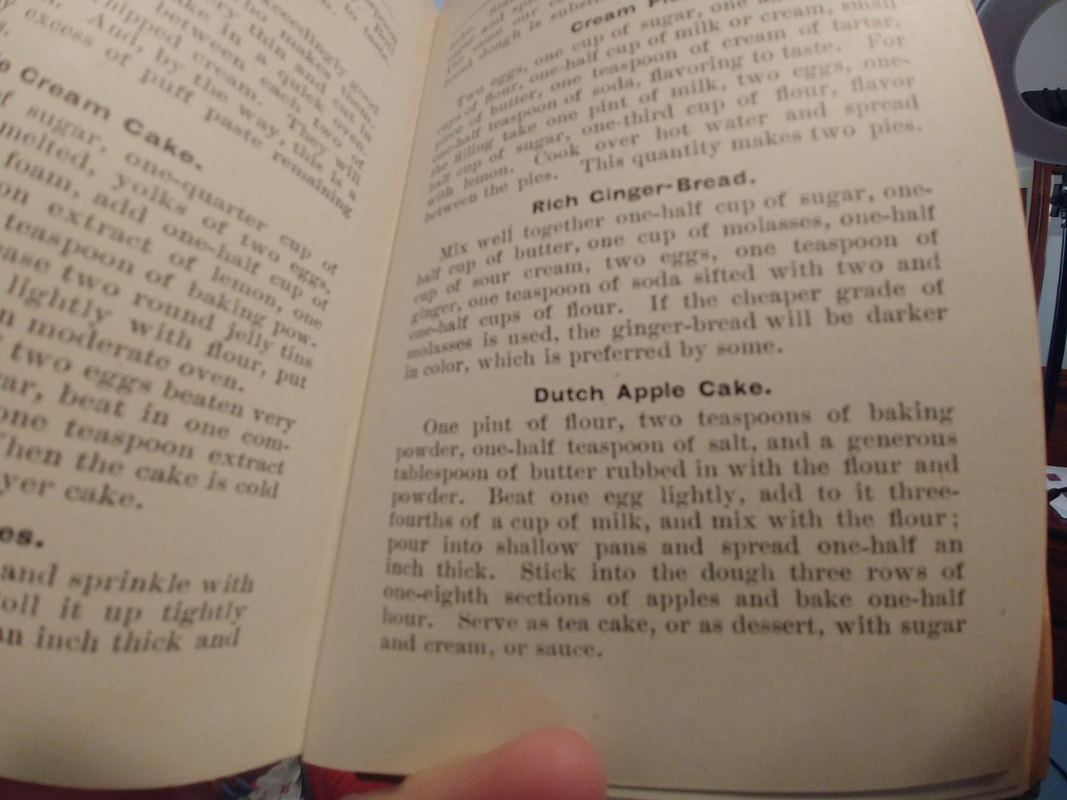

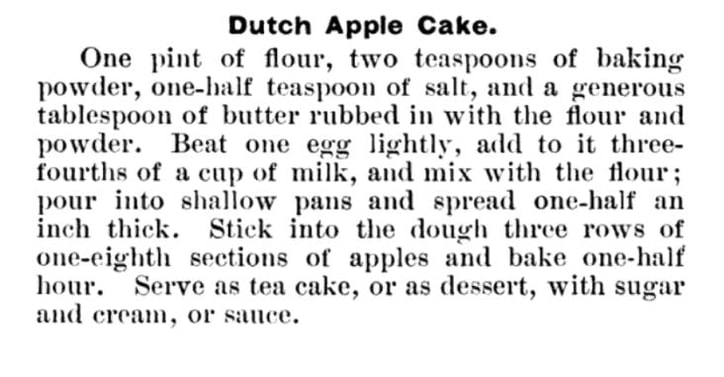

Hood's Practical Cook's Book from 1897 is one of my favorite 19th century cookbooks in my collection. It's really quite small and could easily fit in an apron pocket. My copy has the original dust jacket, which is nice. Published by C.I. Hood & Co., a Victorian patent medicine company, the cookbook is interspersed with advertisements for Hood's products, especially their famous sarsaparilla extract. I made the very successful Buttermilk Cake from this cookbook previously, and I'd been wanting to make Dutch Apple Cake for a while. Touted as a "tea cake," it was essentially a biscuit with sliced apples stuck in the dough. We've been trying to cut back on sweets, and this recipe has absolutely no sugar in it - neither for the biscuit nor on the apples, so it seemed like a perfect dessert. I also made it for our 3 year wedding anniversary. Normally we go away someplace fun, but obviously not this year, so I made my favorite roasted vegetable French lentil bowls and we had this for dessert. Dutch Apple Cake Recipe (1897)The original recipe reads: "One pint of flour, two teaspoons of baking powder, one-half teaspoon of salt, and a generous tablespoon of butter rubbed in with the flour and powder. Beat one egg lightly, add it to three-fourths of a cup of milk, and mix with the flour; pour into shallow pans and spread one-half an inch thick. Stick into the touch three rows of one-eighth sections of apples and bake one-half hour. Serve as a tea cake, or as dessert, with sugar and cream, or sauce." Here's how I translated the recipe: 2 cups flour 2 teaspoons baking powder 1/2 teaspoon salt 1 1/2 tablespoons butter 1 large egg 3/4 cup whole milk 3 smallish apples (I used Gingergold - a sweet, slightly mealy, early apple) Combine flour, baking powder, and salt and whisk to combine. Cut butter into small cubes and smush with fingers, mixing into the flour, but leaving largely intact. Whisk the egg into the milk, and pour into the flour mixture. Toss with a fork until a dough forms, kneading/folding lightly to get the rest of the flour and spread the butter, then pat into a greased quarter sheet pan. Quarter apples, core, and cut each quarter in half (to make the eighth!). I did not peel mine, and pressed into the dough as best I could on their sides. I had a few slices left over. Bake at 350 F for about 30-40 minutes until the biscuit is lightly browned and the apples are tender. Serve with sweetened whipped cream (and liquid cream, and maybe some maple syrup). If you read the recipe, it seems pretty straightforwardly biscuit-y. But when you get to the middle, it says, "pour into shallow pans and spread one-half an inch thick." Sadly, my dough did NOT pour, and in fact, I had to knead it a bit to get the flour mixed in. If I had been paying closer attention, I would have added a little more milk, but I didn't! So I followed the recipe exactly. The biscuits were also a BIT flat tasting and dry - I would add a teaspoon or so of sugar and more milk (at least a cup), which I think would make something a little more batter-ish, which would presumably rise around the apples a little more. I would also space the apples closer together as they provide the only sweetness. In summation, certainly not a terrible recipe, but not great either. Basically a plain biscuit with baked apples on top. Sadly, this one gets labeled a fail! But I am going to try it again - I might also add some sweet spices like cinnamon or cloves to the biscuit dough and see if that makes a difference. And maybe chop the apples into smaller chunks - not as pretty, but easier to eat. Have you ever tried a recipe and had it fail in some way? Share your trials and tribulations in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

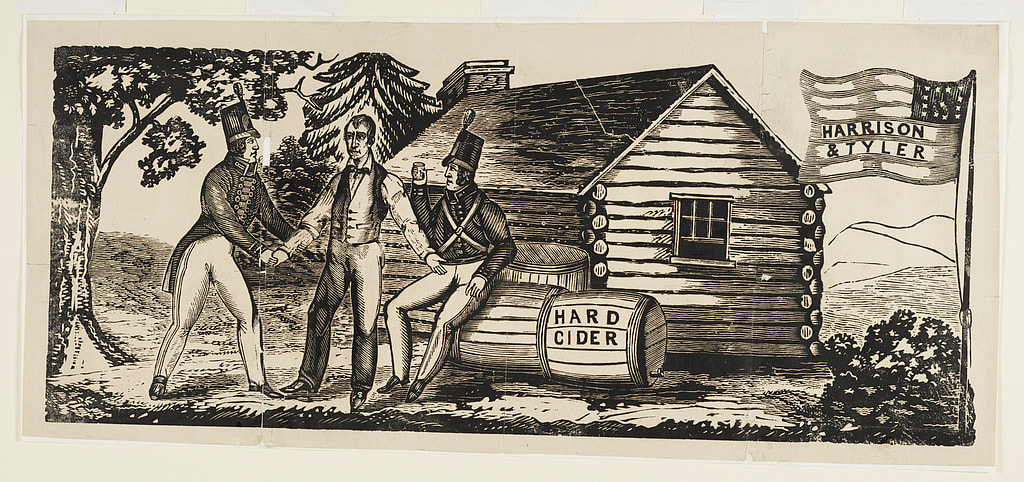

An untitled woodcut, bold in design, apparently created for use on broadsides or banners during the Whigs' "log cabin" campaign of 1840. In front of a log cabin, a shirtsleeved William Henry Harrison welcomes a soldier, inviting him to rest and partake of a barrel of "Hard Cider." Nearby another soldier, already seated, drinks a glass of cider. On a staff at right is an American flag emblazoned with "Harrison & Tyler." Library of Congress.

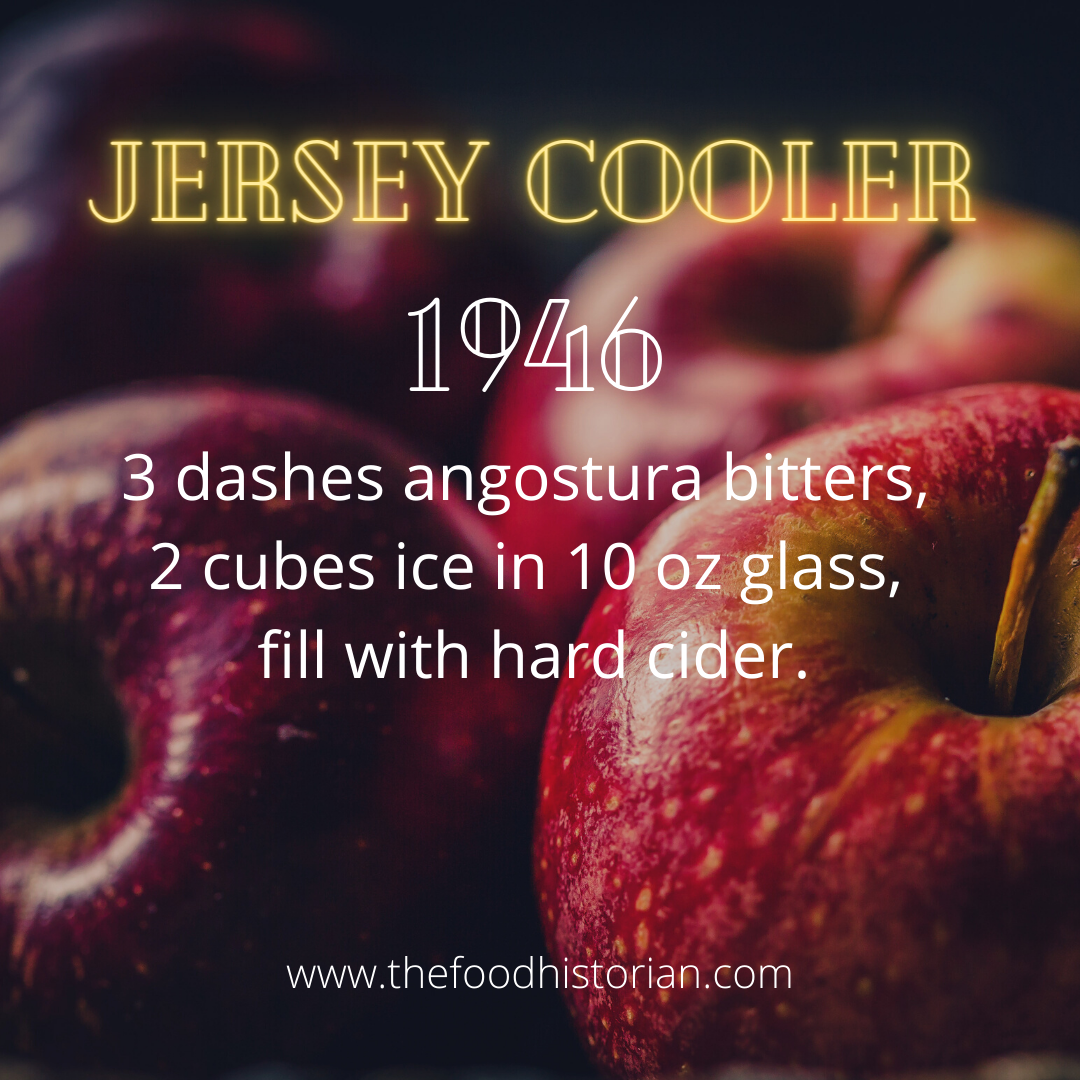

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Jersey Cooler from the Roving Bartenter (1946), but the cocktail itself appears to have been invented by the famous Jerry Thomas as it appears in his 1862 How to Mix Drinks.

With the primary ingredient hard cider, I thought it a particularly apt cocktail for our discussion of apples in America! I chose apples as the topic for tonight's Food History Happy Hour because mid-September is when apple harvest in the Northeast usually really starts to get underway. Coincidentally (on my part, anyway), tonight is also the start Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish New Year, which runs until Sunday. One of the components of Rosh Hashanah is the use of apples and honey, particularly in Ashkenazi Jewish households, who originate in Eastern Europe. Apples and honey are eaten to symbolize sweetness and prosperity for the coming year. On a more somber note, I learned that Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away just minutes before the start of the show. In fact, I almost didn't do tonight's episode because I was so upset. But I figured that the notorious RBG would power through if it was her, and it was fitting to be talking about apples and hoping for peace and prosperity in the coming New Year. So we poured one out for Ruth and gave her a toast. We talked about the origins of hard cider, with an aside about the 1840 presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison, why hard cider fell out of favor, the origins of apples in the mountains of Kazakhstan, Johnny Appleseed, the story of Red Delicious, heirloom apple varieties, and the not-so-American origins of apple pie. Jersey Cooler (1946)

From the 1946 Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly:

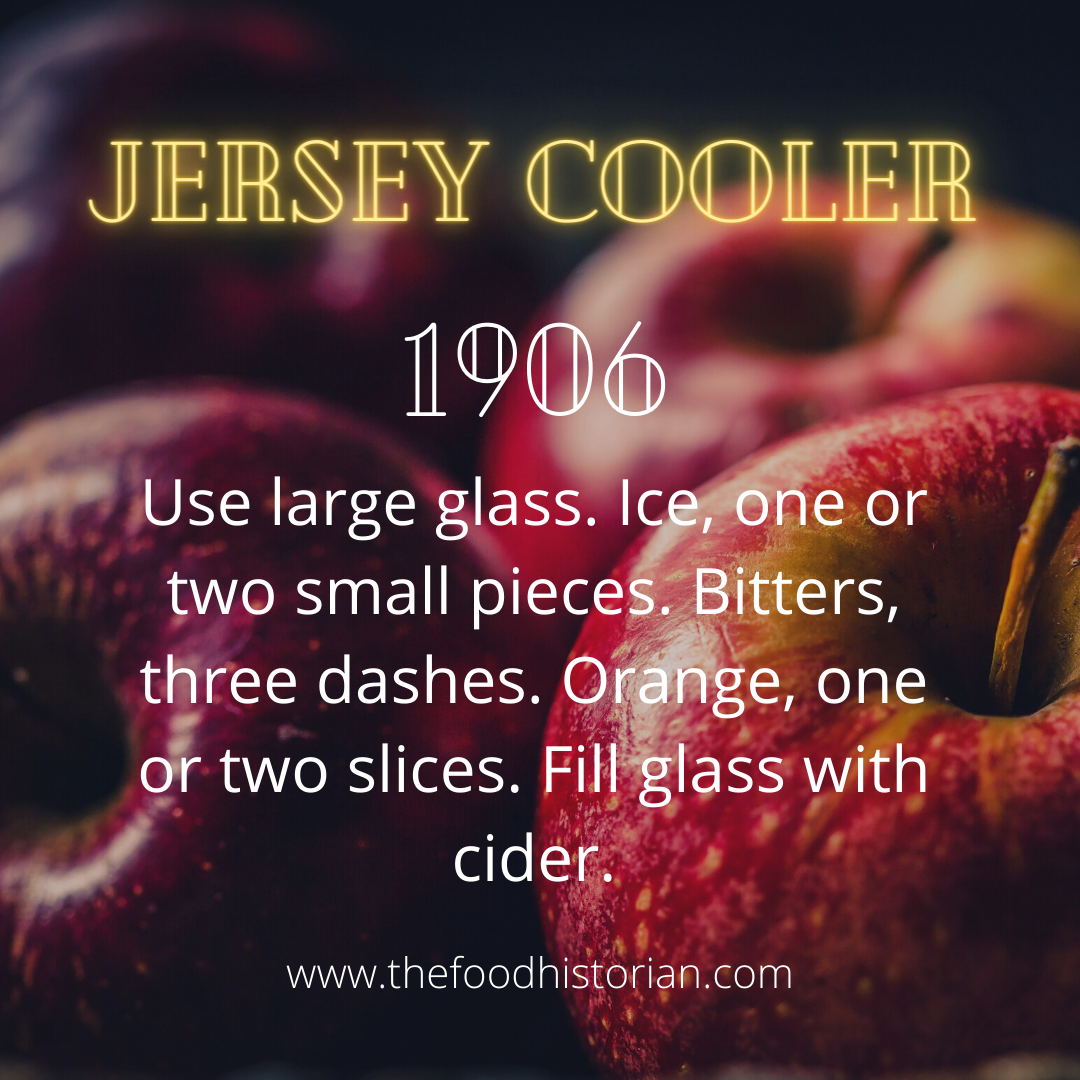

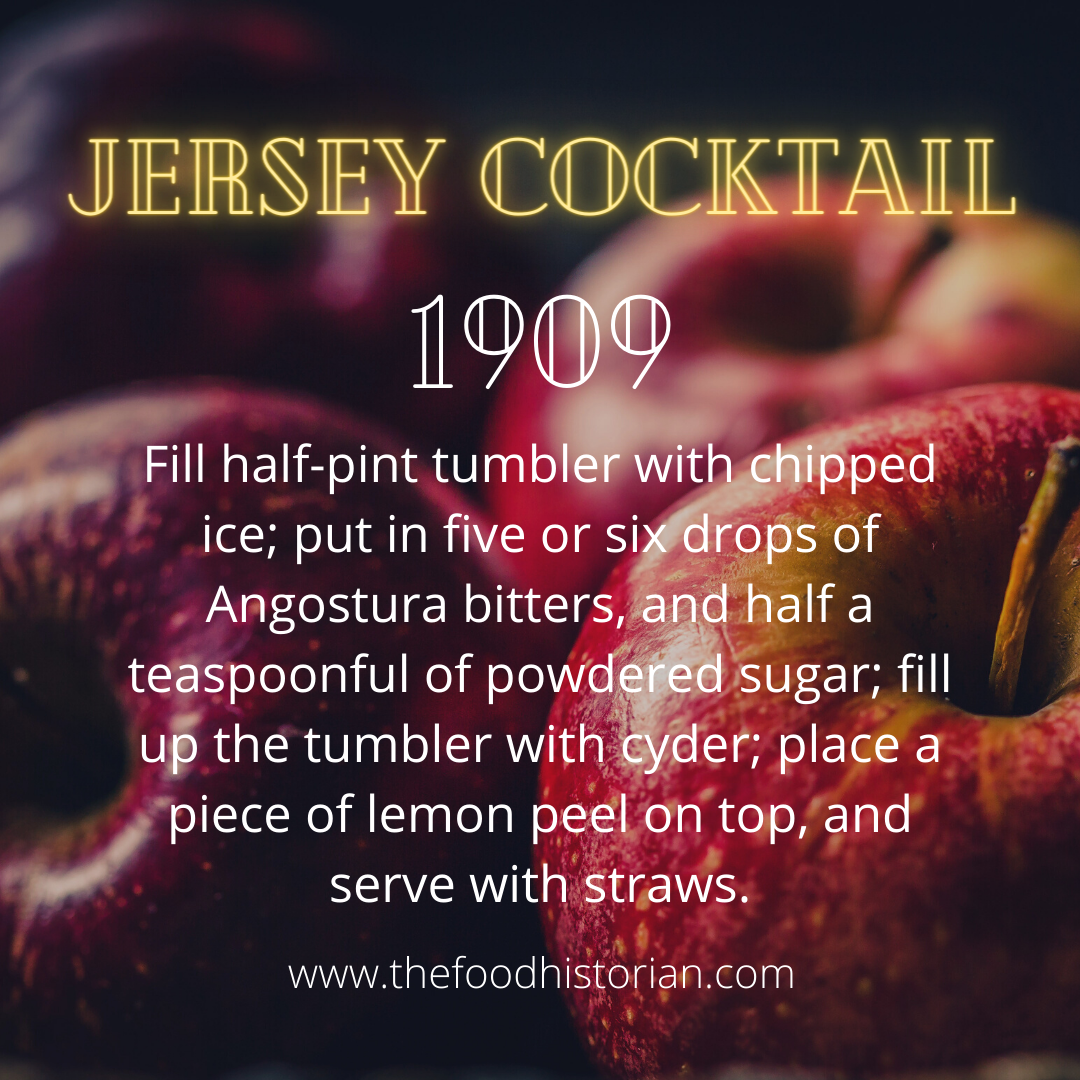

You can see other, slightly more complicated versions below: Jersey Cocktail (1862)

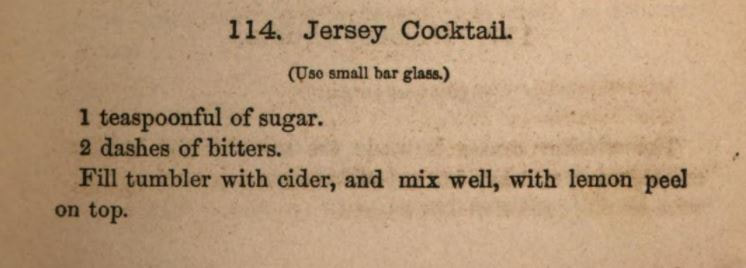

As far as I can tell, this is the oldest version of the Jersey Cooler (called cocktail here), invented by the famous Jerry Thomas from his How to Mix Drinks from 1862. Because the earliest reference is from Mr. Thomas, who was a born and raised New Yorker, I think that the "Jersey" in this instance refers to New Jersey, not Jersey, England.

Here's his recipe: (Use small bar glass.) 1 teaspoonful of sugar. 2 dashes of bitters. Fill tumbler with cider, and mix well, with lemon peel on top. Episode Links

Our next episode will be on Friday, October 2, 2020 and since it will officially be October, we'll be talking about pumpkins and the origins of the much-maligned pumpkin spice!

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed