|

I can take zero credit for coming up with this genius recipe. That 100% goes to Nevada and her North Wild Kitchen, which is where I first found her recipe for rømmegrøt ice cream. You may be asking yourself, what on earth is rømmegrøt? Rømmegrøt is a traditional Norwegian porridge made from flour and heavy cream, usually served with cinnamon and sugar at Christmastime. The term rømmegrøt means "sour cream porridge," and in Norway the traditional recipe often calls for a mixture of sour cream and milk. But for whatever reason, here in the States, it is almost exclusively made with plain heavy cream. Interestingly, as far as I can tell, the taste is not particularly different, because this ice cream is made with sour cream and it tastes exactly like the rømmegrøt I grew up eating. (If you're interested in the original rømmegrøt, check out my patrons-only post on Patreon, complete with a recipe!) The "real" rømmegrøt is incredibly rich. The flour makes for a smooth, creamy pudding-like texture and as it cooks with the heavy cream it "splits" and "makes" its own melted butter sauce as the flour binds to the dairy proteins in the heavy cream. Historically its richness made it the perfect food for winter holidays, which is why it is so often associated with Christmas. This is also perhaps why soured cream was used, instead of fresh. Cows generally stop producing milk once their offspring are weaned, so winter is the time a lot of cows would "dry up" until they got pregnant again. If a family only had one cow, it would be impossible to get fresh dairy year-round. Rømmegrøt is also a traditional dish for new mothers - the rich but easily digested food helped them recover from the trauma of childbirth, and ensured they got enough calories to keep their babies well-fed. But while this food is, indeed, delicious, eating a rich, stick-to-your-ribs dish in the summer heat is not exactly appealing. Enter the genius rømmegrøt ice cream. Any purchases from links below will result in a small commission for The Food Historian. Rømmegrøt Ice CreamI'm giving you this recipe because although Nevada's North Wild Kitchen recipe is marvelous, I tweaked hers just a little. Fair warning that you will need an ice cream maker for this one. (We got this one as a wedding present and love it.) 12 ounces full fat dairy sour cream (1/2 of a 24 ounce carton) 1 1/2 cups heavy cream 3/4 cup granulated sugar 1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon In a pourable container, mix all ingredients and whisk well to combine (you could stop at this point and just eat the pourable mix with a spoon, and I always lick the bowl). Pour into the ice cream maker and start. When the ice cream is no longer turning over in the maker, it's pretty much done. You can pack it into a freezer container (these are nice) or serve immediately. Rømmegrøt ice cream has a tangy sweet flavor and including the cinnamon in the ice cream makes all the difference, for me. You can eat it on its own, but it also pairs well with apple pie or crisp, blueberry, blackberry, rhubarb, or strawberry desserts, and gingerbread. I had originally intended to make a big strawberry rhubarb crisp for the party to go with this ice cream, but ran out of time. And since I made two batches of rømmegrøt ice cream in advance, it almost got forgotten altogether! I pulled it out last minute for anyone who had room for a little more dessert. While everyone enjoyed it, I think I was the only one who had ever tasted rømmegrøt before, so perhaps it's slightly less of a delight without the taste memories to work with. I guess this just means I'll have to throw a Scandinavian Christmas party to introduce everyone to the joys of original rømmegrøt! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

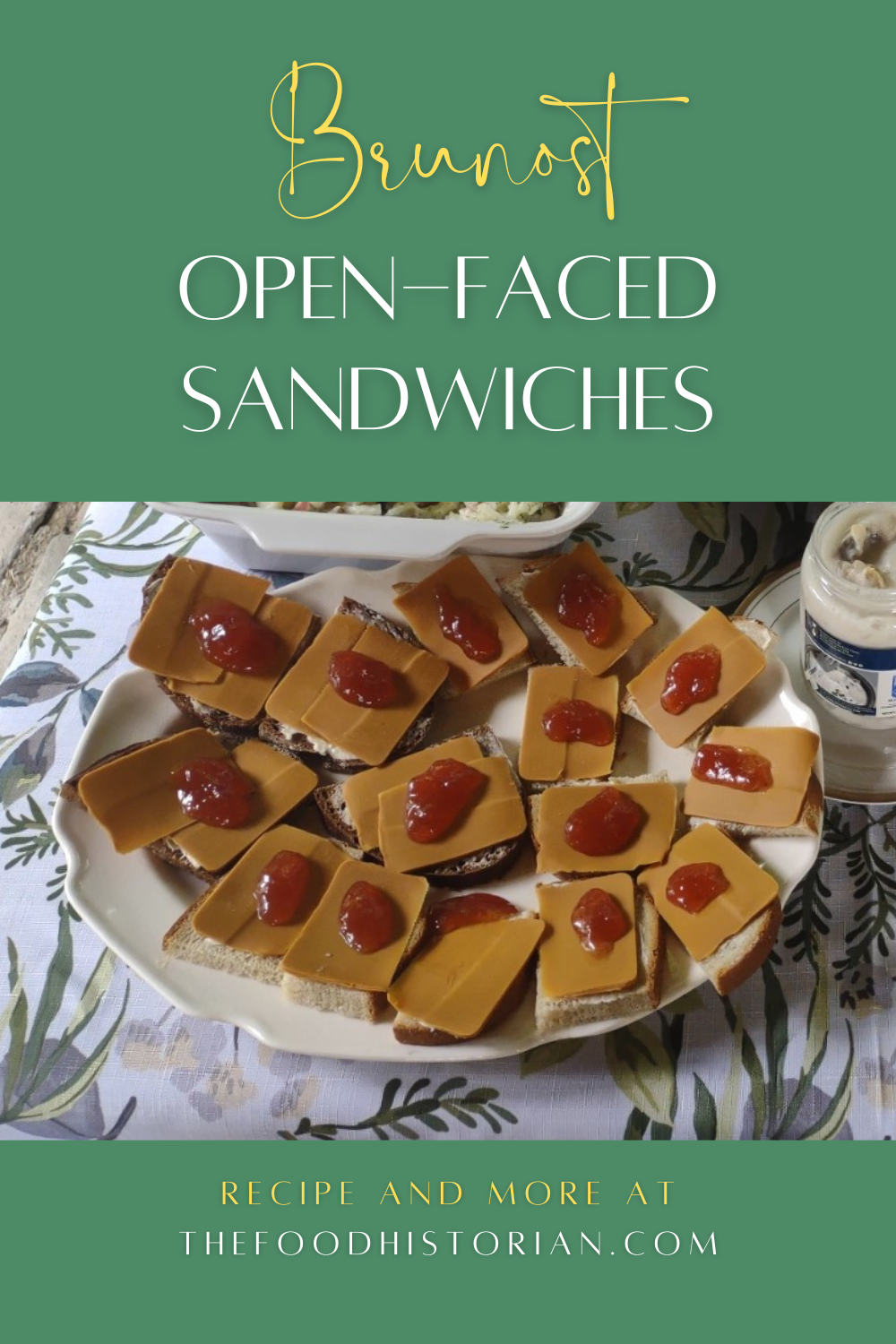

These were, shockingly, the runaway smash hit of my Scandinavian Midsummer Porch Party. And here I thought no one would like them! But they were the first to go of the open-faced sandwiches on offer and the only ones to have every last sandwich devoured. I probably should have made more... You may be asking yourself, what the heck is a "Ski Queen Brunost Open-Faced Sandwich?" Dear reader, Ski Queen is a brand of brunost widely available here in the United States. And what exactly is brunost? And how is it different from gjetost? Did you even know you needed the answers to these questions? Brunost is literally Norwegian for "brown cheese," and it is a very special, very specific style of cheese that is not really a cheese at all. Made from caramelized whey, this super-smooth, sweet and salty cheese can be made from either cow's milk whey (brunost) or goat's milk whey (gjetost). Whey-based cheeses, or mysost, date back over 2,000 years in Scandinavia, with the earliest evidence found on Jutland, Denmark. Going back hundreds of years, Norwegian dairy farmers perfected the use of whey, the milky yellow liquid leftover from processing butter. The original brown cheese, mysost, was literally just whey boiled until all the water evaporated and it caramelized into a sweet, grainy, fudge-like substance. But brunost is cow's milk whey that has cream and milk added in, which makes it creamy, smooth, and addictive. This addition is attributed to dairywoman Anne Hov, who helped revive the failing dairy industry in Gudbrandsdalen, Norway, in the 1860s. Later variations included goat's milk (gjetost) and "ekte gjetost" or "real goat cheese" is a brown whey cheese made from only goat's milk whey and goat's milk - it has a much stronger flavor than brunost and a sweet-salty tang. Brunost was typically served with open-faced sandwiches, on Norwegian heart-shaped waffles, or eaten plain as a snack. Modern cooks have used it in all sorts of ways, but one of my favorites is a creamy gjetost sauce for chicken. Today, most commericial brunost is produced by Tine - a Norwegian dairy cooperative that started in the 1850s and is named after the special bentwood boxes Norwegians used to store butter in the days before refrigeration. Tine also produces Jarlsberg. In the United States, you can get the cow's milk brunost and goat's milk ekte gjetost under the Ski Queen brand, so named because of the association in Norway of brunost with skiing, since brunost holds its shape under a wide range of temperatures, and its sweetness and fat helped replenish energy after a long day of skiing. Brunost Open-Faced SandwichesThis really will win converts. If you want to be bold, have a tasting of both the milder, sweeter brunost and bolder gjetost. thinly sliced buttered rye sliced brunost a dollop of strawberry jam You'll need your ostehøvel to get appropriately thin slices - a knife will be too thick. Make sure to get high quality strawberry jam - not too sweet, not too thick (my favorite is Welch's natural strawberry). These little sandwiches are basically like grownup candy. You can see why they are so popular in Norway and why almost everyone who tries it loves brunost. Have you ever tried it? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed