|

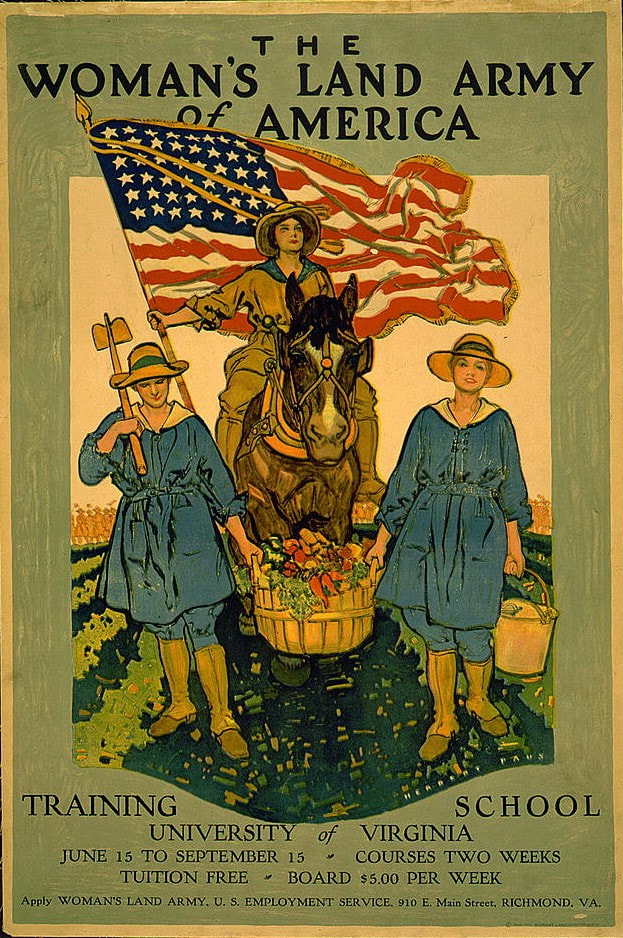

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase something from a link, you'll be supporting The Food Historian! The Woman's Land Army of America came out of the women's suffrage movement as a way for young, largely college-educated women to prove their worth during wartime by providing agricultural labor to make up labor shortages thanks to the draft, better wages in industrial work, and the need to increase agricultural production. The movement started in New York State, and has been ably chronicled by Elaine Weiss' book The Fruits of Victory. This beautiful propaganda poster from the University of Virginia Training School for the Woman's Land Army of America is just delightful. The imagery is evocative. A young woman holding an American flag, which billows out behind her, is dressed in a khaki uniform and riding a plow horse through a green agricultural field, simultaneously calling to mind a mounted standard bearer, Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders, and Army cavalry. In the foreground, two young women in matching blue uniforms share the load of a bushel basket laden with vegetables. The woman at left has a hoe over her shoulder, reminiscent of how a soldier might carry a rifle. The woman at right carries what appears to be a milk pail. Far in the background, what appears at first glance to be a field of ripe wheat is in fact a golden line of uniformed women with agricultural implements on their shoulders, marching behind the leading three. The costumes were among the official Woman's Land Army costume - in khaki and blue chambray. A loose tunic with full sleeves (rolled up) and a cinched waist falls to the knee, covering military-style jodhpurs and puttees over sensible shoes. A broad-brimmed hat and a kerchief around the neck complete the sensible outfit, which somehow still scandalized some members of the public at a time when women's skirts rarely rose above the ankle. The poster is advertising the Woman's Land Army's Training School at the University of Virginia. Designed to give young women basic agricultural skills, and sometimes specialized skills like the use of tractors, the schools were generally free, but required payment for room and board, as this one does at $5.00 per week for a two week course. Sometimes called "farmerettes," likely a combination of the terms "farmer" and "suffragette," and one which not every member of the Woman's Land Army enjoyed. But then, not every farmerette was a member of the Woman's Land Army, and the term actually predated the U.S. entrance into the war. The women saw some success in the adoption of their labor in agriculture, but it created no sea change of labor distribution post-war. Most farmers outside orchards and truck farmers mechanized in the face of labor shortages, rather than using farmerettes or farm cadets (teenaged boys released from school to work on farms). And increasing specialization of crops and livestock meant that mechanization was easier and more profitable than hiring young women at good wages for just 8 hour days (pre-war farm laborers had no such protections). The Land Army would be revived during World War II, this time divorced from its suffragist origins and encouraging young people of both sexes to assist with farm labor. But that's a post for another day. Woman's Land Army Books Fruits of Victory: The Woman's Land Army of America in the Great War by Elaine F. Weiss Weiss tracks the evolution of the Woman's Land Army in America, focused primarily on New York State, which was where the WLA officially began in the U.S. In intimate detail, she introduces us to a whole host of historic characters, including leading lights of the women's suffrage movement, and how they tried to prove women's agricultural labor was the future.  Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement by Cecilia Gowdy-Wygant Cultivating Victory examines the interrelationships between the British and American Woman's Land Armies, as well as their connections to the war garden and victory garden movements. Covering both the First and Second World Wars, Gowdy-Wygant compares and contrasts the efforts in both nations and the differences and similarities between both wars. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

0 Comments

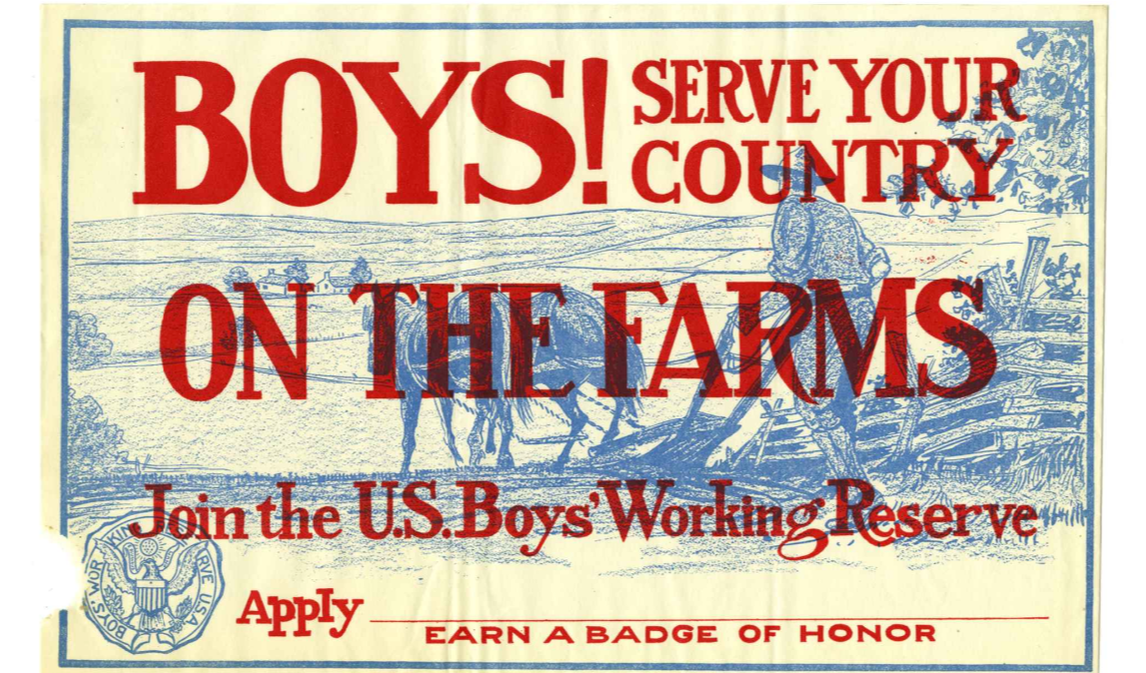

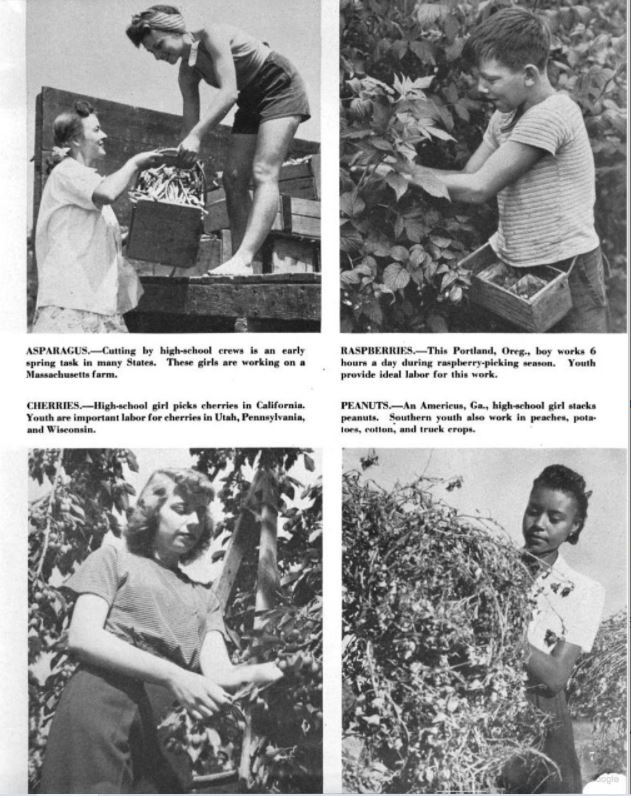

As we enter September (and FINALLY some cooler weather!) I always think of harvest time. Being immersed in finishing my book, I've been doing lots of reading about farm labor (and food preservation and war gardening and all those other fun topics), and Farm Cadets are a topic I've been researching to summarize in the book. During the First World War, very real fears about the food supply led to a whole host of changes to American agriculture, including farm labor. Although farmers lobbied Congress and President Wilson to exempt farmers and agricultural laborers from the draft, they were not exempted. So when the Selective Services Act was passed on May 18, 1917, farmers worried about who was going to harvest their crops. The wages of experienced farm hands began to skyrocket, and state and local governments scrambled to find a solution while the Federal government remained relatively hamstrung by the hold up of the Lever Act which would fund the U.S. Food Administration (and which would not be passed until August, 1917). Indeed, the U.S. Department of Labor would step in to help fill the gap in finding workers for many wartime labor needs. For American suffragists, the Woman's Land Army was a reasonable solution. But rural and agricultural folks are fairly conservative, and the idea of young city women in overalls (scandal!) working their fields was unpalatable for most. Teenaged boys, however, were a good solution, in the eyes of many. Not only were they out or nearly out of school during key planting and harvest times, organized labor camps would train them for military service. And indeed, that's how many of the farm cadet camps were organized - with military tents, uniforms, ranked officers, and military language. The reality of the practice, like that of the Woman's Land Army, was a bit more amorphous. I'm still sifting through the heady propaganda of newspaper articles and official reports versus what actually took place, but it looks like Farm Cadets, which appear to have included girls as well as boys, at least in New York State, did have a positive impact, particularly on fruit harvests, which often needs lots of dexterous manual labor for short periods of time. Gary E. Moore has written a nice overview of the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve, which was a US Department of Labor program started in June, 1917. You can also read a 1918 report from the Bureau of Educational Experiments (no really, that's what it's called), entitled "Camp Liberty: A Farm Cadet Experiment." The Farm Cadet program (like the Woman's Land Army and victory gardens) was revived for service during the Second World War. In 1947, following the war, the United States Department of Agriculture published, "Farm Work for City Youth," a glossy, photo-laden pitch for the value of agricultural labor, rebranded as "Victory Farm Volunteers." In New York State, I have found evidence that the Farm Cadet program lasted, under that name, as late as 1982. With a few unreachable references on Google Books to even further into the 1980s. The need for seasonal agricultural labor today is filled largely by migrant workers, many of whom work in appalling conditions and for poor wages. There have been improvements in recent years as various states implement minimum wage requirements for agricultural workers and mandate things like breaks, restroom facilities, and on-site water. But I wonder, if teenagers (especially white, middle class teenagers) continued to work in agricultural labor on their summers "off" - what would our agricultural labor landscape look like today? If you enjoyed this World War Wednesday history article, please consider joining us on Patreon, which offers special patrons-only perks.

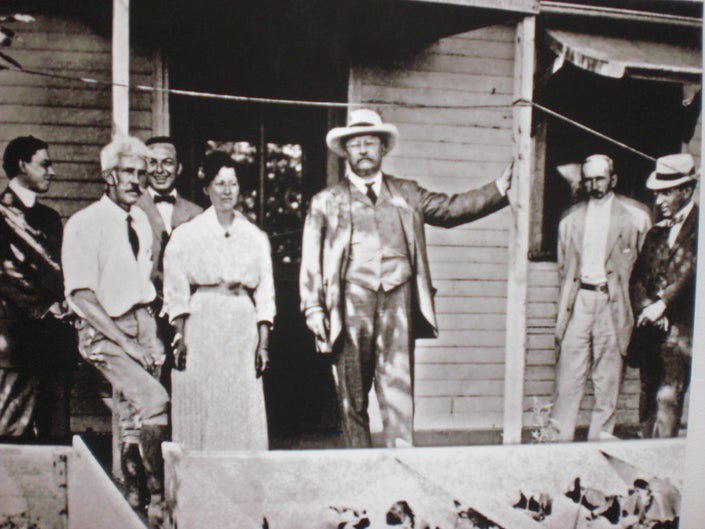

One of the things I do when collecting research for my book is to transcribe newspaper articles. They can be invaluable sources of important information, particularly when filling out a timeline or compiling information about historical people. But they can also be delightfully amusing reads, as this article I came across in New York City's The Sun newspaper, published on June 10, 1917. Farmerettes and women as agricultural labor was a new idea for most people in the First World War, but in New York the use of young, single, white women as paid agricultural laborers dates to 1911. In this article from 1917, the author, Jeanne Judson, visits Hal and Edith Fullerton's farm on Long Island. Hal Fullerton was the agricultural agent for the Long Island Railroad and an agriculture booster in the region. His wife Edith was an accomplished gardener who went on to author books on gardening and canning. This research is for a new chapter in my book on agricultural labor efforts in New York during the First World War. So I have to track down extra information on farmerettes who, believe it or not, lasted in New York State until the 1920s. "Doubting Thomas's Sister Looks Into Possibility of Farming For Women. She Visits a Long Island Farm Where Women Have Been Employed for Three Years and Comes Away Not Only Convinced but Envious." Original caption: "Women Workers Aid in War Time. Two women working plow on farm of New York State Agricultural School at Farmingdale, L. I. After completion of their courses the women will be capable of teaching others the art of farming. The class was established by the New York Women's Section of the Navy League." Underwood & Underwood photographers. April, 1917. National Archives. (Editor's note: This is a verbatim transcription of the article, "Doubting Thomas's Sister Looks Into Possibility of Farming For Women. She Visits a Long Island Farm Where Women Have Been Employed for Three Years and Comes Away Not Only Convinced but Envious," by Jeanne Hudson and published in The Sun on Sunday, June 10, 1917. The photos have been added by me and are not original to the article.) There are thousands of women in America who realize that they would not adorn the uniform of a Red Cross nurse, all masculine realists and sceptics to the contrary. There are even a few women who are in some doubt as to whether after all there may not be a lot of women who can roll better bandages than they can. And besides there are so many other things to do, and when the average woman analyzes the situation, so pitifully little equipment with which to do them. The lists of things to do for the country are so long - motor car drivers (most women don't know much about driving motor cars), wireless telegraphers (after all it does take time to learn that), camp cooks (doesn't sound very alluring and doubtless all the camps will have men cooks anyway); but farm work? When the call to the farms was issued we all - that is all the willing feminine patriots more distinguished for zeal than for training - sat up and took notice. There were training camps formed and the smartest possible khaki uniforms purchased, scarcely more expensive than a really smart bathing suit if one didn't count the boots. Even then there were some women who still sat at home wondering whether, after all, the women could really be of use on the farms. And the result of all this serious thought led one woman to investigate.  Hal and Edith Fullerton (left, in shirtsleeves) with Theodore Roosevelt, c. 1910. Suffolk County Historical Society. Hal Fullerton and Theodore Roosevelt were both members of the Long Island Food Reserve Battalion, which was active in food production and conservation during WWI. The battalion was founded by Long Island Railroad President Ralph Peters. Off for the Farm. There being no feminine form of the term Doubting Thomas, we will have to call her the timid farmerette. She was thoroughly convinced that she ought to be a farmer, but she didn't know how. So she sought the advice of the woman in New York State who probably knows more about farming than any other, Mrs. Fullerton, wife of H. B. Fullerton, who has charge of the demonstration farm of the Long Island Railroad. At 7 o'clock one fine May morning, about an hour after Mrs. Fullerton had breakfasted, the timid farmerette rose and ate a cold storage egg, preparatory to taking the 8:30 train from the Pennsylvania station that would lead her to a real farm and knowledge. Her trip led her through a lot of farms punctuated by small towns. She had seen farms that way before and thought them very pretty, so green in spring and so yellow in autumn. She didn't know why they were so yellow and green, but she had observed that much about them anyway and began to feel encouraged. To be sure she did not see any women working in the fields, with the exception of one old woman, who was hoeing, and that woman didn't have on khaki, just an old frock, not a bit artistic. The timid farmerette doubted if she had ever heard of agricultural volunteers. Even when the train passed Farmingdale there were no signs of feminine activity, but doubtless the school in which agriculture, first aid, diet and wireless telegraphy are taught was not yet open. She was nervous as to whether the train would actually stop at the farm and asked the conductor about it. "We've got to stop; Mr. Fullerton's on board," said the conductor. "You can see him through there in the smoker - the man in uniform." She looked through and saw him, and soldierly appearing man in a Boy Scout's uniform. His hair was gray and the gray mustache combined with the broad brimmed hat made her think of those Western films. So just before the train stopped she talked to him on the platform and introduced herself. "Just talk to Mrs. Fullerton for a few minutes; she'll set everything straight for you," he said in a husky voice. "You see I've been lecturing and I'm a bit hoarse," he explained. "They've created a new job for me. Grub Master of the Boy Scouts. You know what grub is?" "Oh yes, food," answered the timid farmerette. "Food's right; and the biggest thing in the world to-day," said Mr. Fullerton. Contrasts in Clothes. The next minute they were off the train and Mrs. Fullerton was condoling with Mr. Fullerton over his hoard voice and word tortured throat even while she greeted the timid farmerette. Behind her a Boy Scout stood in an attitude of soldierly attention, until his mother sent him off to get some medicine for father's throat. Then they all walked up the flower bordered path together, past the bird's bath and the guinea pigs' hutch and into the cool, wide open living room of the farmhouse. Here Mrs. Fullerton looked at the timid farmerette for the first time thoroughly. The timid farmerette was not clad, as was Mrs. Fullerton, in a short khaki skirt and a shirt waist above and leggings and stout boots below. By contrast the timid farmerette somehow reminded one of the cold storage egg she had eaten that morning at breakfast. There had been good material in her once. But if Mrs. Fullerton thought of this she concealed it. "Mr. Fullerton has just come back from a lecture trip in his capacity of grub master for the Boy Scouts and there are a number of telegrams and letters here that he must see. If you could amuse yourself for a few minutes looking over things, we'll be with you presently." "Certainly, by all means," murmured the timid farmerette and in another moment she was outside again and wondering what to do next. Near the farmhouse was a tall, round building with stairs winding up to the top. "It's got something to do with the water," thought the timid farmerette and she began climbing to get the view. It Looked Very Easy. On top there were seats and the timid farmerette rested there and looked out over things. It didn't look like such a very big farm. Afterward she learned that there were eighty acres in the farm and that there were eighty acres in the farm and that twenty-two acres were under cultivation, but no one would have dreamed that those small squares of green and brown really covered twenty-two acres. There was a building that she guessed to be the dairy and here in the field nearest the house was a man pushing some sort of small plough between rows of green things. Further off she was delighted at seeing a woman bending over other rows of green things. The woman had on a rather short dark skirt and a boy's cap pulled close down over her hair. The timid farmerette decided to go down and talk to the man. He was nearest. When she reached the field the man was at the other end. She looked closely at the rows of green things and decided that they must be clover. They looked just like clover, only she had a vague impression that clover wasn't planted in rows that way. She stood still while the man started up the next row and came slowly toward her. If that was all there was to farm work she could do it all right. As the man drew nearer she saw that he was smiling. He didn't seem to be a bit surprised at seeing an inquiring woman in high heeled slippers waiting for him. He had seen a lot of them in the last few weeks. They were always either dressed like the heroine of his favorite Western drama or else they had on those silly high heeled pumps with silk stockings, and both costumes seemed equally amusing. "I'm cultivating; this little plough is a cultivator," he explained affably before the question was out of her mouth. "Clover?" He smiled more broadly. "No, it's peas; they do look something like. Lots of people make that mistake," he assured the blushing farmerette. "Do you mind - would you be willing to let me try it for one row?" she asked eagerly. Something in the cheerful reluctance with which he assented made her think of a certain fence that Tom Sawyer was once set to whitewash, but she started bravely out, leaning heavily on the slip handles of the plough, while her high heels sank into the soft, black earth. "Take it easy," cautioned the farmer. "Here, let me show you. You go forward and then back a few inches to get a new start, and don't go too deep. Careful - keep in the center of the row, else you'll tear up the plants." An Expert's Opinion. So he walked along outside the field, giving instructions and smiling at some joke that was not to be put into words for the benefit of city folk. They wouldn't understand anyway. Whether the timid farmerette would have tried another row or not the farmer never knew, for before she had finished her row Mr. and Mrs. Fullerton had come out of the farmhouse and were waiting to talk to her. "Now what do you want to know?" asked Mrs. Fullerton. "First, is it really practical? Can women really be of use on American farms and are they really needed?" "They certainly can be of use and they are needed. We have used women on the farm here for the last three years. I'll introduce you to one later. It's her first year on this farm but it is her third summer at farm work." "How about the training camp at Farmingdale?" asked the timid farmerette. "That is useful only as an eliminator of undesirable workers. In the twenty days course any woman can at least discover whether she is fitted for work on a farm. They'll find out something of what farm work really means. It is never easy under even the most favorable conditions, such conditions as you find on a farm like this, and on the average farm it is something like drudgery to the woman who has been accustomed to every convenience and comfort. Here, for example, is where our two women workers live." She pointed to a small portable house. "Come in and I'll show you." Inside the small house was shown to contain four rooms, a living room, a kitchen and two bedrooms, as well as a very nice bath. "They don't eat here," Mrs. Fullerton explained. "All of our farm workers eat in the farmhouse, but you would have to search far on American farms to find farm laborers provided with a private bath, comfortable sleeping rooms, and a sitting room of their own." Manicurist and Farmer. "The two women who sleep here are Mrs. Thomas Newton, who is the dairy assistant, and Miss Scott, the girl of whom I spoke, who is spending her third summer at farm work. In the winter time Miss Scott is a manicurist and hairdresser. Last winter she worked at the Ritz-Carlton. Mrs. Newton's husband is the farmer who let you run his cultivator. He is our market gardener." "You must see the dairy," said Mr. Fullerton. "Mrs. Fullerton is the best butter maker in America, if you are to believe the medals, and if you don't we'll let you stay to lunch and taste the butter." Mrs. Fullerton has for two years won the highest award for her butter in both Chicago and New York shows. "How do you do it?" asked the timid farmerette. "It's really just a matter of cleanliness; everything about the dairy must be scrupulously clean. If you make sure of that the good butter follows as a matter of course." From the dairy they walked around to another field where Miss Scott was weeding something or other. The timid farmerette felt so crushed with ignorance by this time that she did not ask what, but she had a little prideful swelling of the heart as she clasped the dirt soiled hand of Miss Sadie Scott. One Woman's Experience. The young woman pushed her boy's cap back a bit from her eyes and talked in a modest way about her work. "No, it isn't just a patriotic thing with me," she said. "I've always liked farm work. This is my third season. I worked one year on a farm in Michigan. They took me because they wanted workers very badly and I had to work right along with the men. "It was too much for me; women can't really stand as much manual labor as men can, you know. Then last year I worked on an estate in Westchester." She laughed softly, "It's funny how I got on there. They only consented to give me the job because the women in the house thought it would be nice to have someone at hand who could wash their hair and manicure their nails. That's my work in the winter time, you know. "But this is my first chance at anything like scientific farming. If I had any money I would have gone to agricultural college. It's what I've always wanted. Here I am learning things." She pulled up a plant and showed the timid farmerette some funny little knots on the roots. "That's where the plant is storing up nitrogen," she explained. "The roots are left in the ground and the nitrogen fertilizes the soil for next season's crops." "We never buy any chemical fertilizers here," said Mrs. Fullerton. "We keep the soil in good condition by a proper rotation of crops." "Do you think that I could be of some use?" asked the timid farmerette as they walked back toward the farm house. "Every woman in America can be of use. First by economy in her own home. Second, if she has any land at all, even a kitchen garden, by raising the things that will last - potatoes, cabbages, turnips and such vegetables as can be stored for winter use. If every woman just raises enough for the needs of her own family she will be doing a great service, for then her family will not have to draw from the national food stores. "Above all I think that the woman who cans things for the soldiers to eat is rendering the greatest possible service to her country. One of the biggest needs of the soldiers in Europe has been fruit juice. The demand for jam has become a popular joke, but there is nothing funny about it. It is a real need and this year not one particle of fruit must be allowed to go to waste. That's the reason for the canning train that the Long Island Railroad is sending out over Long Island to teach women how to preserve food. "It isn't just fruit, either. Almost everything can be canned, spinach, asparagus, chicken, tomatoes, corn and even eggs. "We've been canning ourselves this week. Come in and I'll show you." She led the way to a small building. "It is really the children's schoolhouse but they are away at school now and have lent it to us for canning. These little cans are rhubarb and orange marmalade and these are spinach. Every woman in America can help in this work. "I don't imagine that there will actually be many women working on the farms this year. But they are at least learning something of farm work, and next season when the men are fighting they will be prepared to take their places. "The principal thing is to see that not one bit of the crop this year is wasted. Apples must not be allowed to lie on the ground and rot. Vegetables must not be thrown away. Even the woman who lives in the city and cannot raise anything herself can at least buy while vegetables are cheap and can them to use in her own home next winter." The Doubter Convinced. It was noon and the timid farmerette tried very hard to be reluctant about accepting the hospitable invitation to lunch, but somehow in that atmosphere of sincerity she couldn't do it and ended by admitting that she was hungry and that nothing she could imagine would be more welcome than sitting down at the long table in the farm dining room and having what Mr. Fullerton modestly admitted was a regular meal. "We have to eat in town sometimes," he explained, "and we always regret it. I don't see how city people live on the stuff they eat." Under ordinary circumstances the timid farmerette would have been a bit ashamed of the quantity of homemade bread and prize butter that she ate, but she was beyond shame now. She was wondering between mouthfuls just how she could arrange to pawn her typewriter or sell it outright - after all, she never wanted to see it again - and get a job on a farm. Mr. Fullerton was telling her about the Boy Scouts - how they mobilized almost five thousand of them in three days and how they were busy doing their bit for the Grub Master. Free Land for Women. Mrs. Fullerton told her how they had offered the uncultivated land of the farm free to any women's organization that wanted to take it over for cultivation. "No one has accepted the offer so far," she said. "They are all eager to do something, but I suppose there must have been some difficulty about getting funds to build the necessary barracks for the accommodation of the women. We offered them water and light and the land free of charge, but no one has taken it up. It is too bad that so much land should lie idle." The timid farmerette thought cynically of women's cavalry corps and like useless organizations parading on Fifth avenue, but she did not voice her sentiments. Somehow she couldn't when she found herself taking the train back to New York without having asked for a job on the farm. Habits are hard to break, and even while she thought of the demonstration farm her ears caught the roar of the approaching city and she sighed a bit and decided to wait for a while before she sold the typewriter. Wasn't that a delightful article? If you'd like to learn more about the Woman's Land Army of America, which was the main (but not only!) thrust of farmerette activity during the First World War, check out the excellent book The Fruits of Victory by Elaine Weiss. As for the rest of the farmerette story in New York? You'll have to wait for my book! Edith Loring FullertonSadly, the main holders of all things related to Hal and Edith Fullerton, the Suffolk County Historical Society, don't seem to have much about them online and as far as I can tell neither have a Wikipedia page. But all of Edith's books are in the public domain. So if you'd like to read them, just click on the links below!

Hal Fullerton, who was significantly older than Edith, was the agricultural agent for the Long Island Railroad, and when he retired the position went to Edith. When she died in the 1930s, the position at the Railroad was retired. If you enjoyed this transcribed article from 1917 and would like to support my book and writing work, please consider becoming a patron on Patreon! Patrons get special perks like members-only content, including access to draft chapters of my book.

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. Thanks to everyone who joined me on Friday for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week we discussed the role of riots and boycotts in history and food history, touching primarily on the food boycotts and riots and high cost of living protests of 1916/1917 which occurred around the globe. We also talked about women's suffrage and farmerettes, midnight suppers, Frank Meier, inventor of the bees' knees cocktail and his role in WWII, poison candy and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, food and riots or protests, including the role of food and cooking in the Civil Rights movement, Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Little House Cookbook, L. M. Montgomery, requests for next week, and a brief introduction to the history of gelatin, beaten biscuits, and other formerly upper-crust foods which became inexpensive convenience foods. If you want to watch back episodes you can check them out on right here on the blog or I am hoping to upload full episodes to YouTube now that my channel is officially verified! Bees' Knees Cocktail (1936)In 1936 Frank Meier published "The Artistry of Mixing Drinks," a beautifully designed little bartender's guide based on his time as the head bartender at the Hotel Ritz Carlton's Cafe Parisian, which opened in 1921. Frank had purportedly trained at the Hoffman House in New York City before taking on his new role at the Ritz. He served as head bartender and host for over twenty years and even played a role in the French Resistance during WWII, when the Ritz became German headquarters. Meier was a well-known originator of cocktails, including the famous "Bees' Knees," which he invented sometime in the 1920s. It became popular in the United States during Prohibition, likely because the honey and lemon masked the taste of bathtub gin. Frank's original recipe reads: "In shaker: the juice of one-quarter Lemon, a teaspoon of Honey, one-half glass of Gin, shake well and serve." A more modern recipe might be: Juice of 1/4 lemon (or half a tablespoon) 1 or 2 teaspoons of honey 1 or 1 1/2 ounce gin Shake over ice and serve in a cocktail glass. One teaspoon of honey definitely wasn't enough for me - I couldn't taste the honey at all! Perhaps "a dollop" might be a better descriptor. Here are some resources on some of the topics we discussed tonight:

Next week we'll be discussing Easy Bake Ovens, Jello and aspic, foods of the 1950s and '60s, and all sorts of other fun stuff. See you then! If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

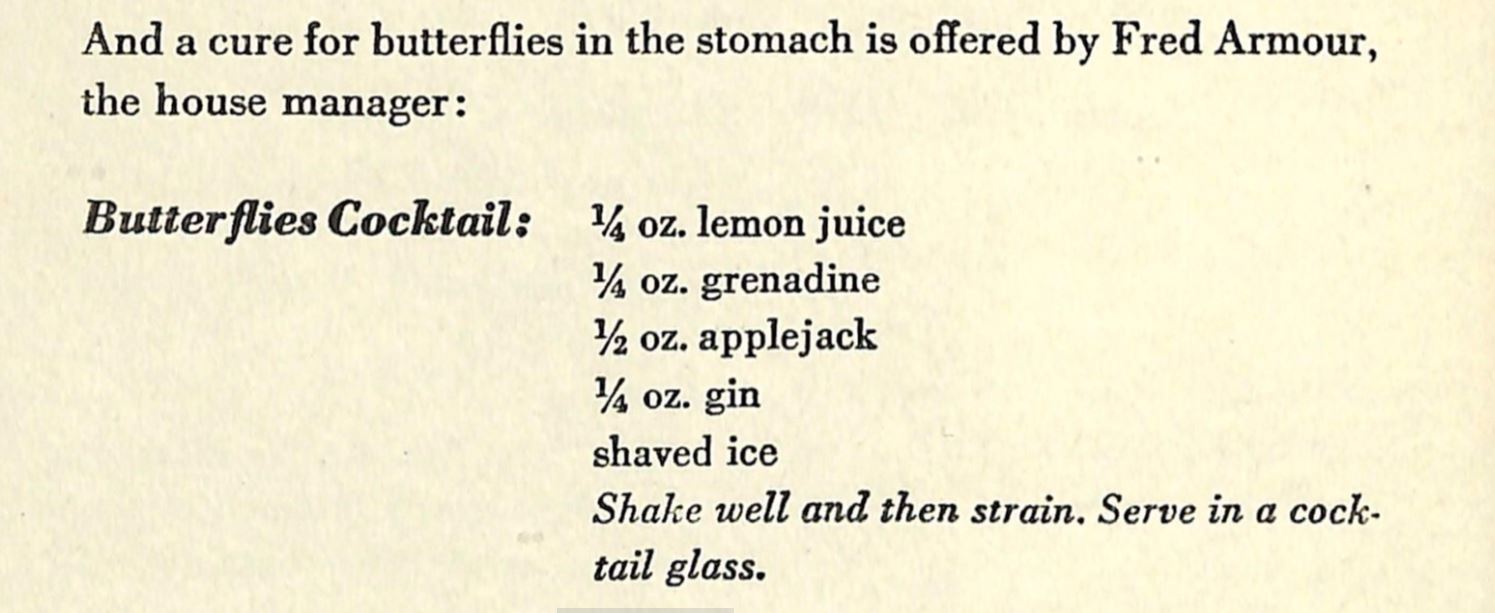

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, inspired by spring, all the flowers in my lawn, and supporting the pollinators, we made the Butterflies Cocktail from the Stork Club Bar Book (1946) and talked about edible flowers! We also discussed back of the box recipes, my latest published book review, farmerettes, Elizabeth's excellent question - 5 Recipes New Cooks Should Master During Quarantine, which I outline, and a discussion of lard, modern pork production, and how to render your own animal fats. Butterflies Cocktail (1946)So when I took note of this cocktail many weeks ago, I completely missed that it was designed as a "cure for butterflies in the stomach!" It still tastes like Kool-aid. And Glenn, you and Carla were right! It IS from the Stork Club, but the digitizing website has a typo in the title and referred to it as the "Stock Club." Hence the confusion. 1/4 ounce lemon juice 1/4 ounce grenadine 1/2 ounce applejack 1/4 ounce gin shaved ice Shake well and then strain. Serve in a cocktail glass. Water PieAnd! As a bonus for those who watched the whole video, here's where I first found out about the Great Depression's ingenious "water pie." If I find more, I will update! If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

A farmerette in a field near Syracuse, NY in her official uniform of jodhpurs, puttees, and tunic. Note the holes in the knees of her breeches. She appears to be forking clover hay. A farmerette in a field near Syracuse, NY in her official uniform of jodhpurs, puttees, and tunic. Note the holes in the knees of her breeches. She appears to be forking clover hay. One of the best things about being a historian is when the research leads you down new and unexpected paths. In editing and updating my book manuscript, I've been doing research on "farmerettes," also known as the Woman's Land Army of America. Farmerettes were young women, mostly white, middle- and upper-clsas teachers, shop girls, and college girls, who worked to prove the worth and strength of women by providing agricultural labor during the First World War. I hadn't originally planned to include much more than a mention of farmerettes, largely because Elaine Weiss did such a fantastic job chronicling the history of the Woman's Land Army of America with her book The Fruits of Victory. But the funny thing about life, and historical newspaper research, is that sometimes you come across a little tidbit that takes you in a whole other direction. My tidbit was a rumor about an original building used by the WLAA in Marlborough, NY. The building is still standing (for now - the owner may soon be developing the property, but there's a campaign to move it) but when I started researching "farmerette" and "Ulster County" a whole host of articles popped up and I realized something important - although the WLAA was founded in 1917, most of these articles were from 1919 and 1920. So I started doing a little more digging, and stumbled across this: The Farmerette Newsletter appears to be first published in January, 1919 (although numbers two and three are both from January, 1919, I have not been able to track down volume one, number one). The first article reads:

"The Secretary of Labor has approved an agreement which makes the Land Army a Division under the Department. He has said, in taking this step, that it will be well for us to play for greater activity next summer, and emphasizes the importance of training women in agriculture. In this action of the Government, there is not only a very welcome recognition of the work that has been done, but also a definite program. "It is no longer a war program; but our peace program still includes the feeding of the hungry in the Old World. We still have to "help Hoover," and Hoover has pledged to Europe twenty million tons of food in 1919. This will not be possible without more than normal farm labor. Therefore the Government has said that the Land Army is not to demobilize, but is to be directed as a part of the nation's service from Washington." What. The Woman's Land Army of America started out as an all-volunteer copycat of British organizations and was strongly tied to women's suffrage movements. And yet, by 1919, here it was partnering with and possibly even being subsumed by the Department of Labor, a fact that seems unlikely, but appears to be very true. This is what I love so much about food history - in this one primary source we have insight into the history of agriculture, women's suffrage, and the post-war labor shortage. The revelation that the Woman's Land Army of America coordinated with the Department of Labor puts a whole new spin on the movement, and illustrates the impact of the Great War on labor in America. Ultimately, the farmerette movement seems to have died out by the close of 1920, perhaps because agricultural labor was not exactly a lucrative endeavor for young women who expected more from life. At any rate, the later years of the farmerettes are going to join surplus food riots, labor shortages, agricultural advancements, and other post-war events and innovations in their own little chapter in Preserve or Perish. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed