|

Note: This article includes descriptions of wartime violence, genocide, and violence against women. Sensitive readers be warned.

Earlier this year, on Armenian Remembrance Day, President Biden officially declared the actions of Ottoman Turkey against Armenians during the First World War to be genocide. While some people might be aware of the Armenian genocide, I think fewer Americans are aware that it was part of the First World War.

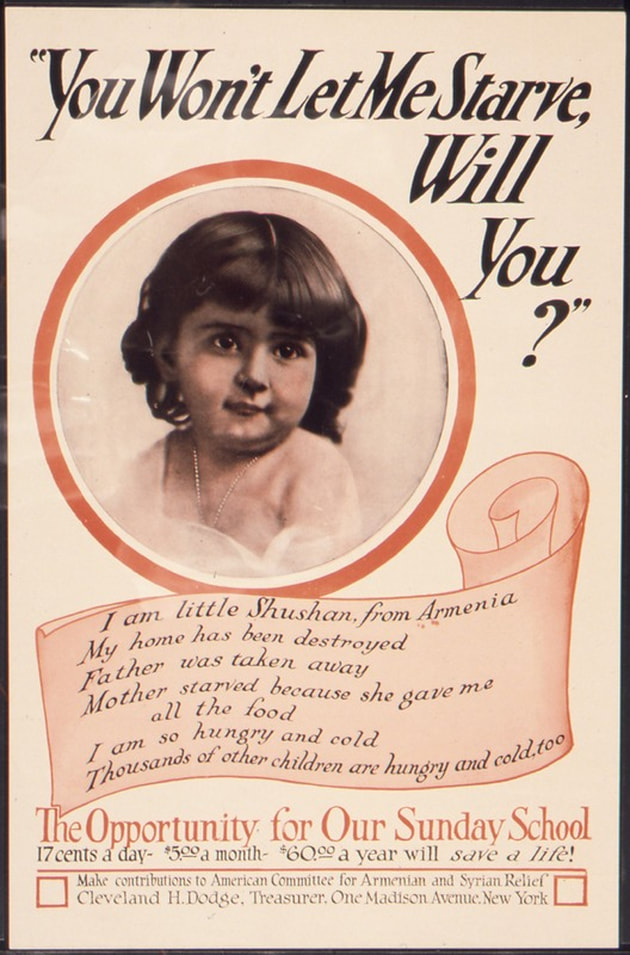

In the above poster, "You Won't Let Me Starve, Will You?" "Little Shushan" says, "My home has been destroyed. Father was taken away. Mother starved because she gave me all the food. I am so hungry and cold. Thousands of other children are hungry and cold, too." Directed specifically at Sunday Schools and children to raise funds for the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian relief, this poster is just one of the appeals made to Americans for charitable support for war-torn regions of Europe and the Middle East. Americans in 1915 were intensely aware of the actions of the Ottoman Empire as it was widely covered by newspapers. Like many campaigns that used starving children in Belgium to raise relief funds or exhort Americans to change their eating habits, Near East Relief and Armenian and Syrian Relief efforts were undertaken as charitable endeavors. The United States never declared war on the Ottoman Empire, perhaps at the behest of relief organizers. But without military intervention, the genocide continued as late as the 1920s. Armenians were Orthodox Christian in a predominantly Muslim Turkish empire. Russia, Turkey's enemy, was also predominantly Orthodox Christian at the time, meaning Armenians were largely branded a "fifth column" of seditious enemy spies living within the borders of the empire. This attitude was exacerbated by the Battle of Sarikamish, in which the Ottoman forces attempted to invade Russia between December, 1914 and January, 1915. Unprepared for the winter weather, the Ottoman military lost more than 60,000 men in a resounding military defeat. In retreat, the Ottomans indiscriminately burned, looted, and massacred Armenian villages near the border. The Ottoman military commander blamed the Armenians for the defeat, saying they had sided with the Russians. This set off a whole host of anti-Armenian violence, despite the fact that many Armenian men had enlisted in the Ottoman military. By the spring of 1915, the Ottoman Empire had launched a campaign of extermination against the Armenians. The lucky ones were able to escape. The not so lucky ones were systematically massacred or sent on forced death marches. The few Turkish politicians who protested were threatened with assassination. Any Muslim caught harboring an Armenian was threatened with execution. Many Armenian men who were massacred were rounded up and taken away from their villages to be killed. So many bodies were dumped in the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that the corpses clogged the waterways and had to be disposed of with explosives. The pollution caused disease for communities living downstream, even after the war was over.

Although charitable organizations worked in the "Near East" throughout the war, and Americans did donate thousands of dollars toward food and relief work, the brutality continued. Coinciding with the massacres of men, Armenian women, children, and the elderly were sent on forced marches into the Syrian desert, punctuated by violence. Those few who survived to arrive at camps after marching without food or water, saw their children sold to childless Muslim families, and the women systematically raped. Those who survived to 1916 and 1917 were ultimately also massacred, so the Empire could avoid freeing them after the war. In all, more than 90% of the Armenian population in the Ottoman Empire was killed or deported, a number scholars estimate at between 1.5 and 2 million people.

The "Lest They Perish" poster above illustrates an Armenian (or possibly Syrian) woman with a child on her back standing in the midst of a bombed-out village. Despite the best efforts of the charitable organizations trying to help Armenians, most of them did, indeed, perish.

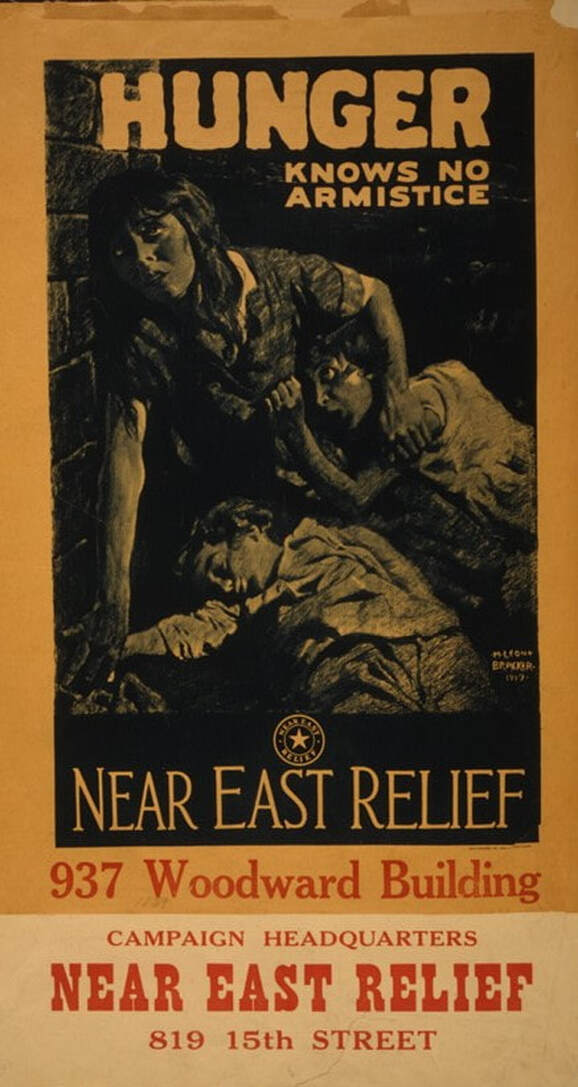

The use of hollow-cheeked women and children in war-torn regions was designed to pull on the heartstrings (and pockets) of Americans of all ages and backgrounds. Propaganda posters by charities like Near East Relief began in 1915 and continued until after the war, along with the genocide. Government-sponsored killings largely ended by 1917, but massacres continued on and off and widespread starvation threatened those who had managed to survive. This poster, "Hunger Knows No Armistice," succinctly points out that starvation was the post-war threat.

Near East Relief was founded in 1915 in Syracuse, NY as the American Committee on Armenian Atrocities, in reaction to reports from Henry Morgenthau, Sr., who was serving as American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Morgenthau was a German-born Jew appointed by Wilson to serve as ambassador in 1913 - a position he initially refused because of Wilson's idea that Jews were well-suited to serve as a bridge between Christians and Muslims. He ultimately accepted the position, and although his work at first consisted mostly of protecting Jewish residents and Christian missionaries, he was soon absorbed by the plight of Armenians in the Empire. Despite his frequent reports of genocide and violence against civilians, the United States remained officially neutral. Frustrated by the Turkish government's refusal to stop the killings, and by the American policy of non-interference, Morgenthau resigned in 1916. In 1918 he published Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, an accounting of his conversations with Ottoman officials about the genocide. However, during his tenure as Ambassador, he was the primary contact for the organization that would become Near East Relief, and was in charge of disbursing charitable donations in Turkey. After his 1916 resignation, it is not clear who disbursed funds, but fundraising continued. In 1919 the committee became only the second charitable organization in American history to receive a Congressional charter. The American Red Cross had been the first. And although charitable efforts continued, they could not stem the tide of genocide. The following video from Facing History & Ourselves, outlines the work of Morgenthau, the Committee on Near East Relief, and the American response (or lack thereof) to the Armenian genocide.

Near East Relief continued their work, focused largely on rescuing Armenian orphans and housing and educating them in a complex system of orphanages inside and outside of Turkey. In 1922, with the burning of Smyrna, Near East Relief evacuated 22,000 children into neighboring states. Evidence suggests that Greek and Armenian neighborhoods in Smyrna may have been purposely set alight by Turkish soldiers. The Muslim and Jewish quarters remained undamaged by the fire. Greek and Armenian residents of Smyrna were subjected to additional massacres, rape, and deportation, both before and after the fire.

In 1930, Near East Relief pivoted to become the Near East Foundation, working on education and economic development efforts in the Middle East and Africa. It still exists as a charitable organization today and the Near East Foundation has created a museum and archive about its organizational history and origins in the Armenian genocide. The U.S. Government never declared war on the Ottoman Empire. There was no military intervention. After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the Treaty of Sevres, and subsequent overthrow of Sultanate with the Turkish Revolution, there was an opportunity to create an Armenian state, which Woodrow Wilson had apparently been in favor of. However, his dreams of reorganizing the Middle East were dashed. The new Turkish government and Bolshevik Russia simultaneously invaded and partitioned the old Armenian Republic before Wilson's plan could be implemented. This led to the creation of both the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic and the absorption by Turkey of portions of the former Armenian Republic, confirmed by the 1922 Treaty of Moscow between Soviet Russia and the new Turkish state. Despite ample first-person evidence of the horrific, systematic, and state-sponsored massacres, and the promise by the Allied Nations in 1915 that the Ottoman Empire would be held responsible for crimes against humanity, no one was ever prosecuted. In fact, the lack of consequences for the genocide may have inspired Adolf Hitler's death camps. He wrote, "I have issued the command -- and I'll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad -- that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy. Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formations in readiness -- for the present only in the East -- with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?" The rapid fall of the Ottoman Empire following the war likely played a major role in the lack of prosecution, as politicians were killed or dispersed and official evidence destroyed. In addition, it took until the Second World War to establish the United Nations and the criminal court at the Hague. Even so, international recognition of the genocide did not formally begin until the United Nations War Crimes Commission published a report in 1948 establishing what constituted war crimes. The Armenian genocide was cited as prime historical example of war crime and crimes against humanity. But it was not until 1985 that the term "genocide" was officially given to the massacres. Most nations did not officially recognize the Armenian genocide until the very late 20th or early 21st centuries. In fact, the United States, which had put so much effort into charitable work and so little effort into military intervention, only just recognized the genocide this year (2021). The Turkish government still refuses to admit to that the actions against the Armenian people during the First World War amounted to genocide. What is left of the Republic of Armenia became an independent state in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union. Today aligned politically and culturally with Europe, Armenians have transitioned fully to a capitalist economy. But their politics, like those of many nations, remain fraught in the modern era. In 2018 anti-government protests, named the 2018 Armenian Revolution, helped usher in political reforms. But other, older conflicts remain, including the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which recently re-erupted in violence in the fall of 2020. A ceasefire was negotiated, and Armenians evacuated, but lasting peace remains elusive. To learn more about the Armenian genocide, visit the Armenian Genocide Museum of America.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

0 Comments

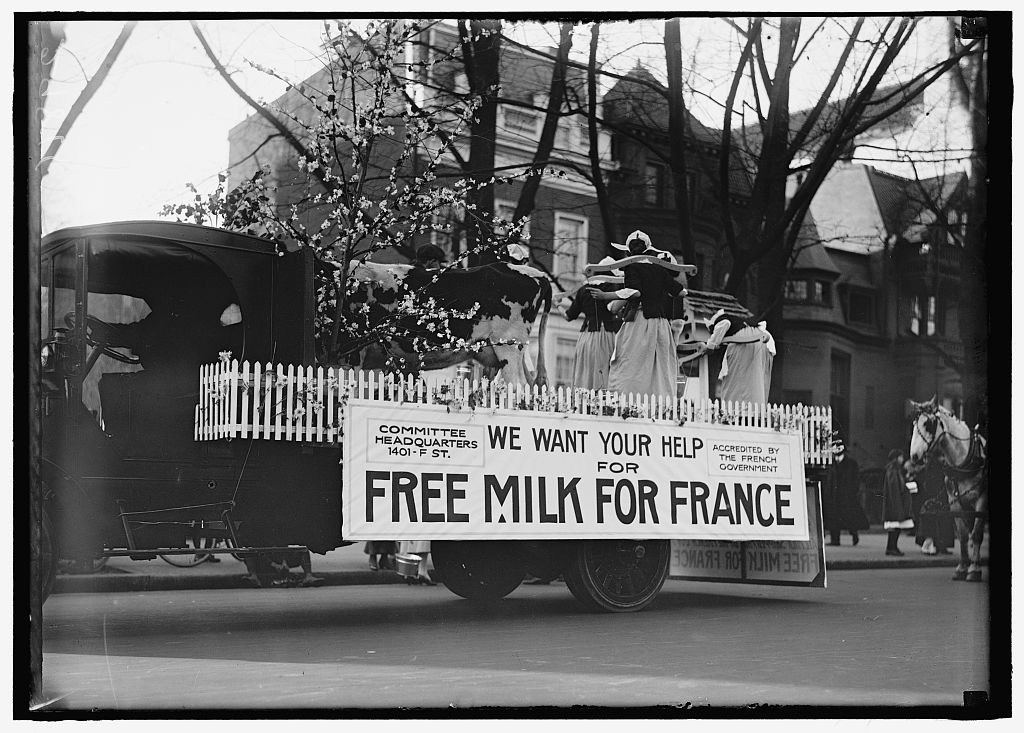

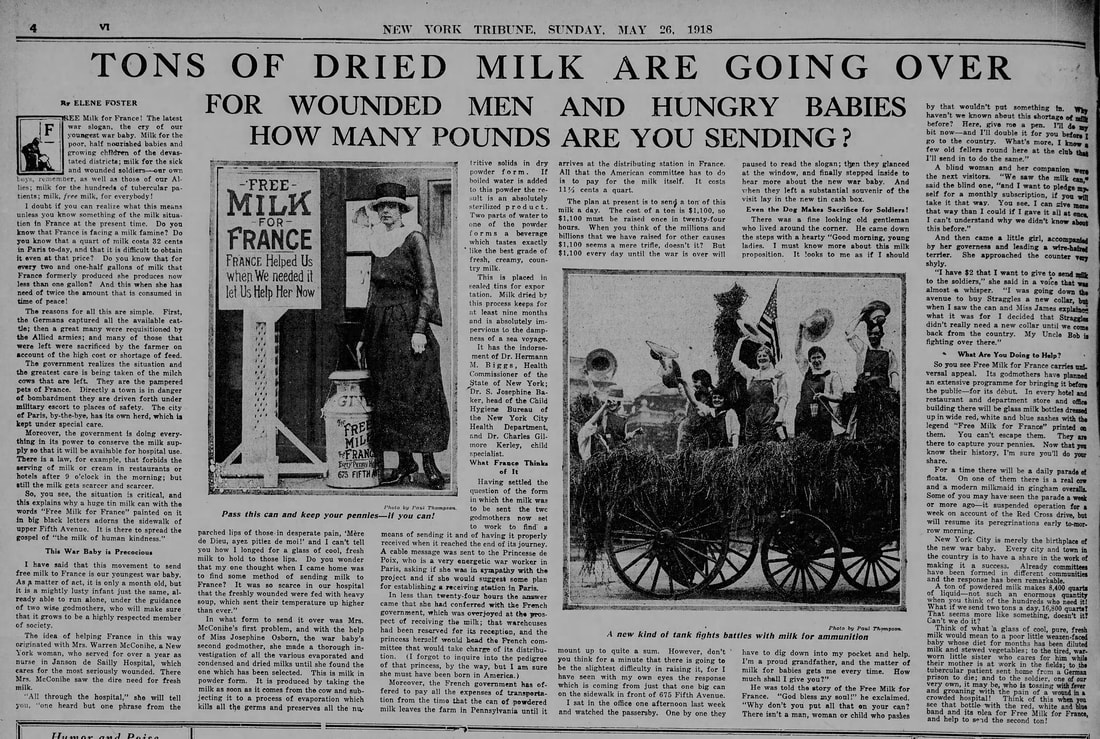

Last week we learned about the big Dairy Exposition during WWI - this week we're examining the Free Milk for France movement, which coalesced about the same time. This propaganda poster by F. Louis Mora from 1918 is one of the more famous of the food-themed propaganda posters of the First World War. In it, a soldier ladles milk out of a large milk can into the bowl of a French child, one of several, accompanied by a wounded French soldier with a tin cup and crutch. Judging by how bundled up everyone is, it's probably winter. Ironically, the Free Milk for France campaign actually focused on provided dried milk. On May 13, 1918, the Committee to Obtain Free Milk for France launched a fundraising parade. "The parade, consisting of two floats and an escort of soldiers and sailors, including a navy band, started from the First Field Hospital Armory at Sixty-sixth Street and Broadway and canvassed the city as far down as the Wall Street District," reported the New York Times the following day. "The money will be used to purchase powdered milk to be sent to France for the use of wounded soldiers, babies, and tubercular patients." In the above photo, a woman dressed in overalls and a straw hat drives a team of horses pulling a large hay wagon. Another woman riding on the wagon is dressed in a military-style outfit holding a small bucket and a wooden shoe - likely soliciting donations. An American flag attached to a sheaf of hay is behind them. The first parade made over $1,000. The group launched another parade a few days later, on May 17th, parading "down Fifth Avenue from Fifty-ninth Street to Twenty-second Street yesterday afternoon." Featuring seven floats, including young society girls "dressed as milkmaids."  Free Milk for France parade, motor truck with a float of milkmaids with a live cow and flowering tree, surrounded by a white picket fence. A large sign reads, "We want your help for Free Milk for France," with smaller notes - "Committee Headquarters 1401-F St." and "Accredited by the French government." Harris & Ewing photographers, May, 1918. Library of Congress. In the above black and white photo, a flat bed truck features a large float carrying a flowering tree, a live dairy cow, and at least five young women dressed as Brittany milkmaids. The edges of the float are surrounded by a white picket fence. On May 19, 1918, the New York Times published "America Sending Milk to France." The article is transcribed below: One of the greatest sources of suffering in France has been lack of milk. The causes for this lack are manifold. In many instances the Germans slaughtered cows for beef whose greater value lay in their milk; in other instances the Government of France requisitioned the animals for army use, and in still others the farmers found themselves forced to kill their cattle on account of the shortage of pasture and fodder. All in all there have been lose to the people of France about 2,000,000 cows, and the main source of maintenance of infants and children, of the crippled and the wounded, the sick and tubercular, lies in milk. At present the death rate of children in France is from 58 to 98 per cent. The number of wounded and crippled needs no repetition here. The increase in the ranks of the tubercular is appalling. Outside Belgium, perhaps, there is no other country which has so greatly succumbed to this disease. The supply of milk in France has been depleted at least 16 per cent. Under present conditions infants must take vegetable stews as a food substitute. What this means to their health and their growth the mortality figures show. Wounded soldiers get heavy soups, which are well-nigh fatal in their effects. The tubercular of France have almost been forgotten. Milk has become a luxury far beyond the reach of the majority of them. In order to do something to meet this situation and to conserve the milk they have, the French Government is taking vigorous measures. Great care is devoted to the protection of milch cows. From bombarded towns, under military escort, two or three at a time are led back to places of safety. Farmers are urged to make all sacrifices possible to provide proper feed for them. Within Paris a herd of cows is kept under civic care. Government restriction now forbids the serving of milk or cream for any purpose in restaurants, hotels, or public eating places after 9 o'clock in the morning. In private homes, rich or poor, milk is only given to young children and the sick. Milk in Paris costs 32 cents a quart, when it can be bought. It was in a desire to do something to change these conditions that Mrs. Warren McConihe and Miss Josephine Osborne organized the Free Milk for France Fund. Mrs. McConihe had seen the soldiers suffering greatly for want of milk, she had seen them grow feverish under the influence of heavier foods. She had seen the Belgian and French refugees almost starved for lack of milk. Upon her return to this country she found that America had enough milk to send some across. Because it requires less shipping space, she chose powdered milk. It is scientifically prepared by subjecting fresh, pure, full-creamed milk to a rapid evaporating process, which preserves the nutritive solids and keeps without ice for months. The milk when prepared costs about 13 cents a quart. There is no other cost. The Government of France has taken over the details of transportation. It is the aim of the organization to send one ton of milk a day. All that is necessary is to mix with hot water. The milk in this form has been recommended even for home use by Dr. Hermann M. Biggs, State Health Commissioner; Dr. S. Josephine Baker of the Child Hygiene Bureau, and Dr. Charles G. Kerley, a child specialist. At a cost of $1,100 a ton of dried milk is sent across, enough to feed 8,400 babies or wounded soldiers or tubercular patients. $52 will send 100 pounds of dry milk or 40 quarts of liquid; $5.20 will sent ten pounds, or forty quarts, and 13 cents will send one quart. The aim of the Free Milk for France organization is to have the nation as a whole respond to its work. Branches are being organized all over the country. The headquarters of the fund is at 675 Fifth Avenue. These two parades, held during the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition, were just the first of a campaign that would last into 1919 and spread across the country. By the end of 1919, there were campaigns in thirty-six states, and the distribution in France was being organized by Madame Foch - wife of French General Ferdinand Foch. The rhetoric around milk and its importance in the diet, especially for children and the sick, would be replicated in the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed