|

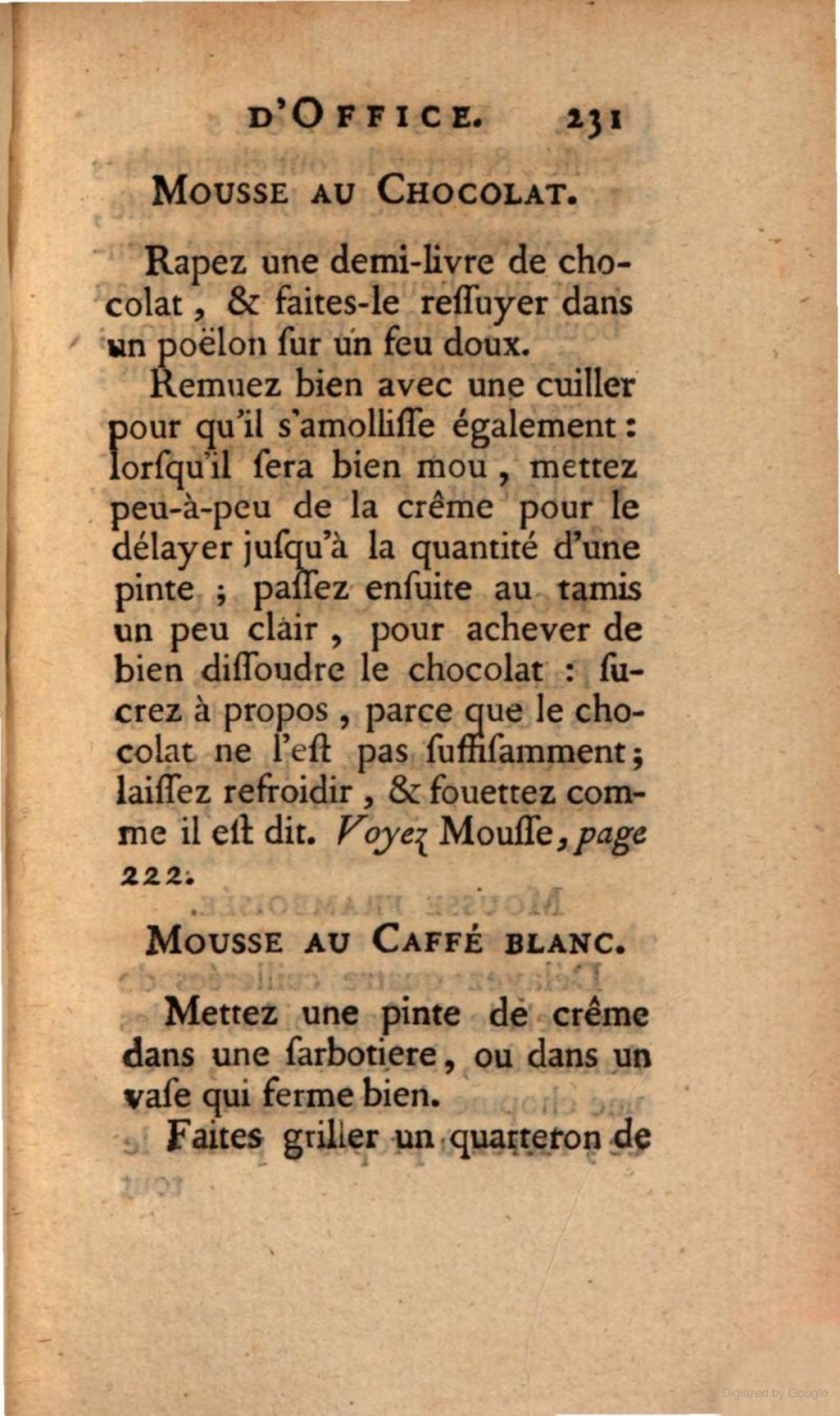

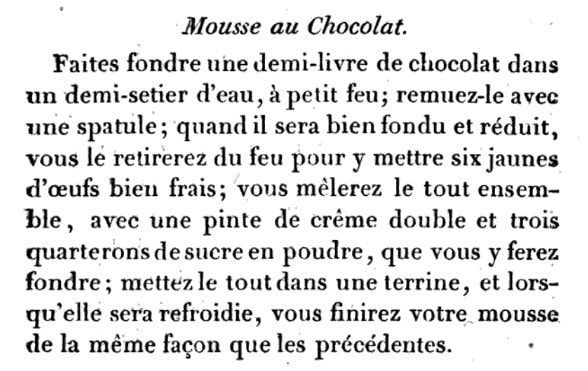

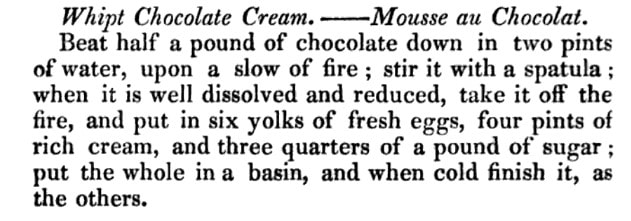

Dear Reader, I finally did it, and not in a good way. A few weeks ago I hosted a beautiful (albeit hot and humid) French Garden Party, a belated celebration of Bastille Day, for approximately 30 people. The decorations were gorgeous and the food was fabulous and I did not take a single. solitary. photograph. My consternation was extreme. My beautiful screen porch was set with tables dressed in blue and white striped linens. It was BYOB - bring your own baguette, and folks brought fancy cheeses to go with the goat cheese and paper-thin ham I provided. I made homemade mushroom walnut pate and TWO compound butters - fresh herb and garlic, and lemon caper. I made beautiful French salads: potato and green bean vinaigrette, lentils vinaigrette with shallot and parsley and a hint of fresh rosemary, cucumber with tarragon and sour cream, celery with black olives and anchovies, peach basil. We had honeydew melon and both sweet dark AND Queen Anne cherries. We had wine and spritzers a-plenty. A friend brought chocolate cream puffs. I made lemon pots de crème and earl grey madeleines. But the absolute star of the show was this chocolate mousse, which I flavored with rose water. And since I had one little glass pot left over from the party, I snapped a few photographs a few days later to give you the incredibly easy recipe so that you, too, may feature this glorious star, and have your guests talking about it for days afterwards (no really - they did). But course, I wouldn't be a food historian if I didn't give you a little context, and I was curious about the history of chocolate mousse, so here you go: A Brief History of Chocolate MousseGoodness there is a lot of nonsense out on the internet about chocolate mousse! Way, WAY, too many sources say it was invented by Toulouse Lautrec, and that it was called "mayonnaise de chocolat." People. Chocolate mousse dates back to at least the 18th century, if not earlier, so it was around long before Monsieur Lautrec. I did, to my surprise, find a couple of recipe references to "mayonnaise au chocolat." It sounds so ridiculous as to be fake, but this was apparently a real recipe, albeit a name I can only date to the 20th century. One recipe is from a 1909 French cookbook, which calls for melting chocolate with egg yolks and adding beaten egg whites, and offers a clue to the name: it says at the end to mix the egg whites and the chocolate mixture "like ordinary mayonnaise." A few references in the 1920s and '30s, and then where it was probably popularized in America - a reference from a 1940 issue of Gourmet magazine (not readable online, alas - if anyone tracks down a hard copy of the original, let me know!). Another recipe is from a 1951 French cookbook, with not very detailed directions. According to my translation, "mayonnaise au chocolat" mixes melted chocolate with egg yolks and a few tablespoons of cream which is then cooked and then mixed with egg whites (unclear whether or not they are beaten stiff or not, but likely yes) and chilled. Another is from the 1961 edition of Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child and Simone Beck, which has a recipe for "Moussline au Chocolat, Mayonnaise au Chocolat, Fondant au Chocolat" (yes, three names for the same recipe!) the subheading of which reads "Chocolate Mousse - a cold dessert." Mousseline is actually a sauce mixed with whipped cream (for instance, you can turn hollandaise sauce into a mousseline by adding whipped cream), whereas mousse is a thickened chilled dessert made with whipped cream. The Julia Child recipe conflates the two, and her recipe calls for an egg yolk cooked custard mixed with melted chocolate, with whipped egg whites folded in. It is then served with crème anglaise or whipped cream. So, none of these recipes are truly chocolate mousse, because the mixtures contain no whipped cream whatsoever. But Toulouse Lautrec and a crazy-to-Americans name like "chocolate mayonnaise" is so much more dramatic than doing actual historical research and looking at primary sources. SIGH. People. We can do better. The earliest references to "chocolate mousse" I could find date to 1687 and refer to the habit of Indigenous peoples in Central America of frothing their chocolate beverages with either a mollinio or by pouring them between cups. A habit which Europeans apparently adopted. A 1701 French dictionary continues the reference to frothy chocolate beverages in its definition of "mousser" or "to foam." The earliest reference I could find to the dessert mousse we know and love today comes from the 1768 French cookbook, "L'art de bien faire les glaces d'office ou les vrais principes pour congeier tous les rafraichissemens" or The Art of Making Ice Cream Well, or the True Principles for Freezing All Refreshments. And lest you think it is just about ice cream, the extremely long title adds, "Ave Un Traite Sur Les Mousses," or "With A Treatise On Mousses." Chocolate mousse (as pictured above) is simply one of dozens of mousse recipes listed, but the early versions are quite similar to the modern. Grate the chocolate and melt it in a saucepan over low heat, then add cream, little by little, to thin it down. Pass it through a sieve, sweeten it, and then let cool and whisk to a foam. By the 19th century, we're adding egg yolks to make a smoother, more custard-y base, as you can see from this pair of recipes by early French restauranteur Antoine Beauvilliers, who published his 1814 "The Art of Cooking" as a French cookbook that became foundational to generations of French chefs and home cooks. English cooks, however, had access before that, judging by this 1812 recipe, which also called for egg yolks. We're still adding large amounts of whipped cream, though, keeping in classic mousse style. It took a bit longer for Americans to adapt to chocolate mousse, although they were prodigious chocolate drinkers, and certainly by the mid-19th century were consuming chocolate custards and ice creams. It wasn't really until (as far as I and the Food Timeline can tell) celebrity cookbook author and cooking school teacher Maria Parloa intervened that it got popular. The Food Timeline cites a 1892 article with Miss Maria Parloa lecturing on chocolate mousse, among other things, but I found a reference dating back to 1885 where she's lecturing on chocolate mousse in Buffalo, NY. However, it doesn't seem to be QUITE the same as we consider chocolate mousse today. Her 1887 recipe for it calls for freezing it like ice cream, albeit without stirring. Regardless of whether the recipe calls for egg yolks or not, or whether it's frozen or not, chocolate mousse in the modern style is easier to make than you'd think. Chocolate Rose Mousse RecipeA French Garden Party called for something easy to prepare and delicious for dessert. Because it was a garden party, I decided on chocolate pots de crème or mousse flavored with rose fairly early on. I used to dislike floral flavors, but after making an Egyptian rosewater dessert last year, and trying Harney & Sons seriously divine Valentine's Day tea, which was chocolate black tea with rosebuds (affiliate link), I was smitten. After realizing how many eggs I'd go through making a triple batch of both lemon AND chocolate pots de crème, I decided to do just the lemon (15 pots) and do the rest as chocolate mousse (15 pots). I found these adorable little glass pots with covers on Amazon, should you care to purchase them yourself from this affiliate link. I adapted several recipes online, and since I didn't want to mess with steeping the cream with rosebuds or rose petals or any other options, I decided to go the less expensive and way easier rose water direction. Rose water is used frequently in Middle Eastern cooking, and is often less expensive in the "ethnic" section than in the spice aisle. In preparing for the party, in which I was attempting a brand new recipe, I didn't want to try to mess with egg yolks any more than I already had to with the lemon pots de crème (which turned out only okay). So the simple mixture of heavy cream, dark chocolate, and a little icing sugar seemed best. I then added rose water to taste, which turned out about perfect. Here's the reasonable-serving recipe, which I tripled to get 15 generous servings for the party. This makes more like 6 servings, 4 if you're being greedy. 1 1/2 cups heavy cream (I used a local dairy brand, which is richer than national brands) 1 cup high-quality dark chocolate chips (like Guittard) 1/4 cup powdered sugar 1 teaspoon rose water Heat a saucepan of water over medium heat, bringing it to a simmer. Place a heat-proof bowl (glass or metal) over the simmering water and add 3/4 cup heavy cream and the chocolate chips. Stir gently until the chocolate chips are completely melted. Remove from heat. In a large bowl, beat the remaining 3/4 cup heavy cream until you get soft peaks, then add the 1/4 cup powered sugar and beat until you get stiff peaks. Add the rose water and beat to combine. 1 teaspoon should be enough to stand up to the chocolate, but taste the whipped cream. The rose water should be present, but not overpowering. If faint, add another 1/2 teaspoon and beat again. Then, using a ladle, add approximately 1/3 cup of the cooled chocolate-cream mixture to your whipped cream, one ladle at a time, and gently fold to combine using a rubber spatula. To fold, use the spatula to cut down the center of the whipped cream mixture and scrape up from the bottom. Rotate the bowl slightly, and repeat the action, until the chocolate is incorporated. Add another ladle of chocolate and continue until you have folded in all of the chocolate without totally deflating the whipped cream. Spoon into small glass jars or custard cups and refrigerate until ready to serve. It was so gorgeous. Light but rich, with a subtle hint of rosewater, which added fascinating depths to the chocolate. Folks gobbled it all up, and it was by far the best dessert of the party. The one lonely little pot left allowed me to take the above photo the following day, so you're welcome! I didn't serve it with whipped cream during the party, and it's admittedly a little overkill, but it does look pretty. So now you have the recipe AND some history, plus some food history mythbusting! So do yourself a favor and go splurge on some high-quality ingredients and treat yourself and your loved ones to this easy and stunningly delicious dessert. To quote Julia, quoting the French, Bon Appetit! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

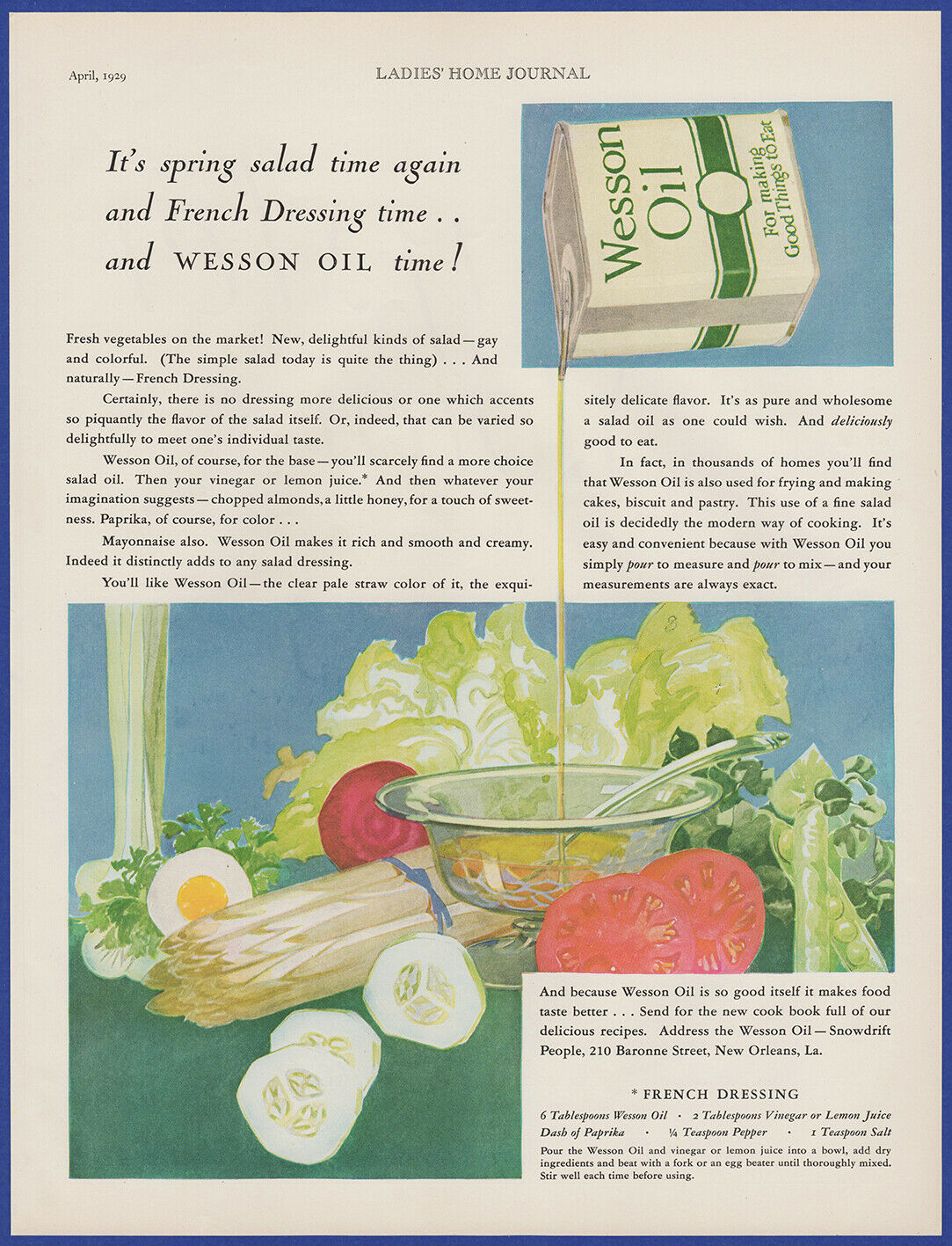

The Food and Drug Administration recently announced that it would be de-regulating French Dressing. And while people have certainly questioned why we A) regulated French Dressing in the first place and B) are bothering to de-regulate it now, much of the real story behind this de-regulation is being lost, and it's intimately tied to the history of French Dressing.

A lot of people like to claim that French Dressing is not actually French. And if you're defining French Dressing as the tangy, gloppy, red stuff pretty much no one makes from scratch anymore, you'd be right. But the devil is in the details, and even the New York Times has missed this little bit of nuance. This Times article, published before the final de-regulation went into place, notes, "The lengthy and legalistic regulations for French dressing require that it contain vegetable oil and an acid, like vinegar or lemon or lime juice. It also lists other ingredients that are acceptable but not required, such as salt, spices and tomato paste." (emphasis mine) What's that? The original definition of French Dressing, according to the FDA, was essentially a vinaigrette? What could be more French than that? In fact, that is, indeed, how "French dressing" was defined for decades. Look at any cookbook published before 1960 and nearly every reference to "French dressing" will mean vinaigrette. Many a vintage food enthusiast has been tripped up by this confusion, but it's our use of the term that has changed, not the dressing. Take, for instance, our old friend Fannie Farmer. In her 1896 Boston Cooking School Cookbook (the first and original Fannie Farmer Cookbook), the section on Salad Dressings begins with French Dressing, which calls for simply oil, vinegar, salt, and pepper.

She's not the only one. I've found references in hundreds of cookbooks up until the 1950s and '60s and even a few in the 1970s where "French dressing" continued to mean vinaigrette. You can usually tell by the recipe - composed salads of vegetables are the most common. If a recipe for "French dressing" is not included, and no brand name is mentioned, it's almost certainly a vinaigrette. So what happened?

I've managed to track down the original 1950 FDA Standard of Identity for mayonnaise, French dressing, and salad dressing. In it, the three condiments are considered together and are the only dressings identified, likely because few if any other dressings were being commercially produced. Although the term "salad dressing" has been extremely confusing to many modern journalists, it is clearly noted in the 1950 standard of identity of being a semi-solid dressing with a cooked component - in short, boiled dressing. The closest most Americans get today is "Miracle Whip," which is, in fact, a combination of mayonnaise and boiled dressing. Generic brands are often called just "salad dressing" because it was often used to bind together salads like chicken, egg, crab, and ham salad, and also often used with coleslaw. So it makes perfect sense that "French dressing" would be the designated term for poured dressings designed to be eaten with cold lettuce and vegetables - i.e. what we consider salad today. People have wondered why we needed to regulate salad dressings, but there is one very important distinction in the 1950 rule - it prohibits the use of mineral oil in all three. Mineral oil, which is a non-digestible petroleum product (i.e. it has a laxative effect), and which is colorless and odorless, was a popular substitute for vegetable oil during World War II by dieters in the mid-20th century. I collect vintage diet cookbooks and it shows up frequently in early 20th century ones, especially as a substitute for salad dressings. Mineral oil is also extremely cheap when compared with vegetable oils, and it would be easy for unscrupulous food manufacturers to use it to replace the edible stuff, so the FDA was right to ensure that it did not end up in peoples' food. Mineral oil is sometimes still used today as an over-the-counter laxative, but can have serious health complications if aspirated. There were several subsequent addenda to the standard of identity, but most were about the inclusion of artificial ingredients or thickeners, with no mention of any ingredients that might change the flavor or context of what was essentially a regulation for vinaigrette until 1974, when the discussion centered around the use of artificial colors instead of paprika to change the color of the dressing. The FDA ruled that "French dressing may contain any safe and suitable color additives that will impart the color traditionally expected." So here we see that by the 1970s, the standard of identity hadn't actually changed much, but the terminology had. "French dressing" went from the name of any vinaigrette, to a specific style of salad dressing containing paprika (and/or tomato). When people started adding paprika is unclear, but it was probably sometime around the turn of the 20th century, when home economists began to put more and more emphasis on presentation and color. A lively reddish orange dressing was probably preferable to a nearly-clear one. In 2000, the LA Times made an admirable effort to track the early 20th century chronology of the orange recipes. By the 1920s, leafy and fruit salads began to overtake the heavier mayonnaise and boiled dressing combinations of meat and nuts. As the willowy figure of the Gibson Girl gave way to the boyish silhouette of the flapper, women were increasingly concerned about their weight, and salads were seen as an elegant solution.

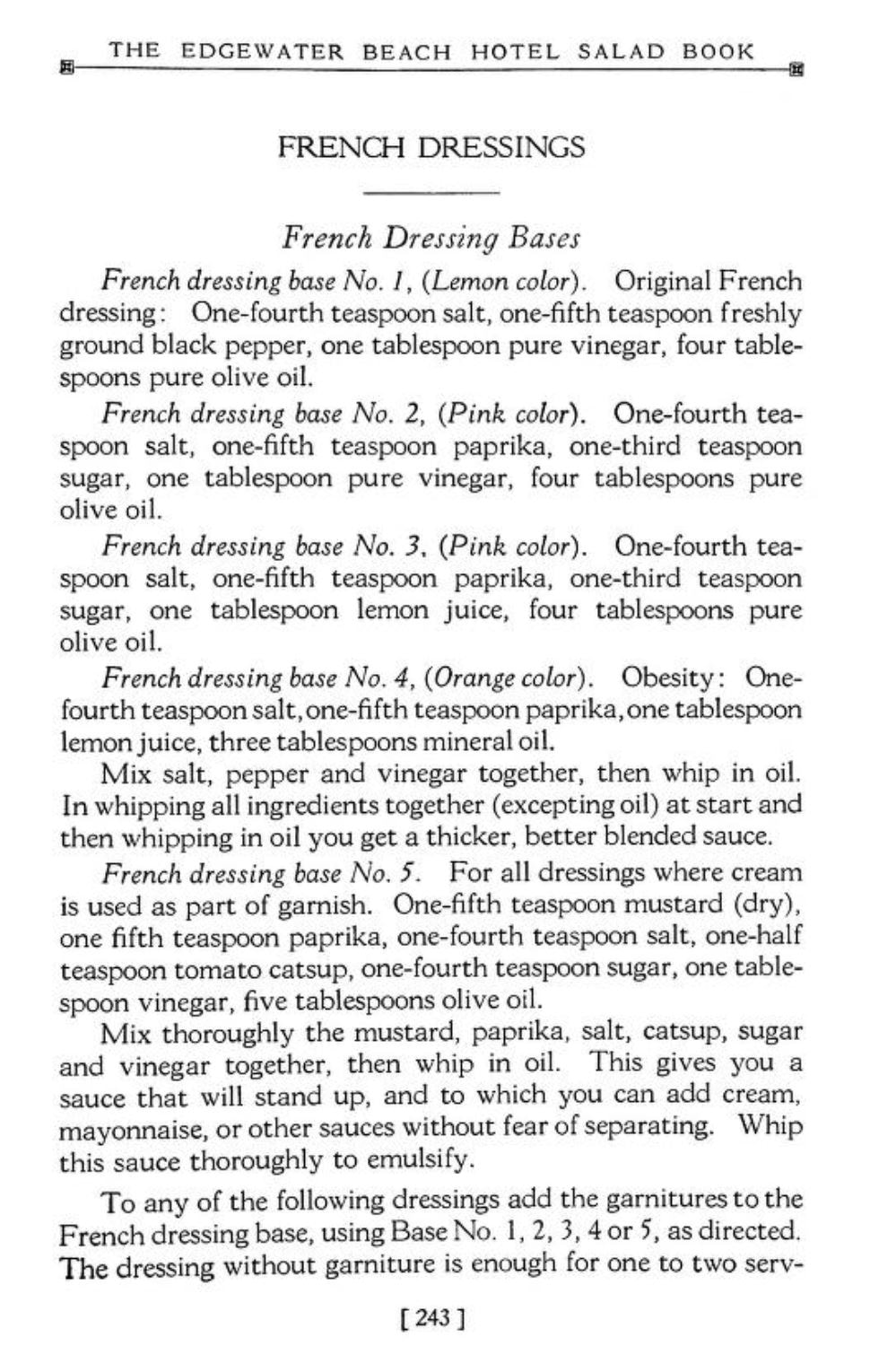

The recipes pictured above are from The Edgewater Beach Hotel Salad Book, published in 1928 (Patreon patrons already got a preview of this cookbook earlier in the week!). The Edgewater Beach Hotel was a fashionable resort on the Chicago waterfront which became known for its catering and restaurant, and in particular its elegant salads. You'll note that several French Dressing recipes are outlined (they are also introduced first in the book), and are organized by color. "No. 4 (Orange Color)" has the note "obesity" not because it would make you fat - quite the opposite - its use of mineral oil was designed for people on diets. Although the fifth recipe does not note a color, it does contain both paprika and tomato "catsup," and all but the original and "obesity" recipes contain sugar. An increase in the consumption of sweets in the early 20th century is often attributed to the Temperance movement and later Prohibition.

By the 1950s, recipes for "French Dressing" that doctored up the original vinaigrette with paprika, chili sauce, tomato ketchup, and even tomato soup abounded. My 1956 edition of The Joy Of Cooking has over three pages of variations on French Dressing. Hilariously, it also includes a "Vinaigrette Dressing or Sauce," which is essentially the oil and vinegar mixture, but with additions of finely chopped pimento, cucumber pickle, green pepper, parsley, and chives or onion, to be served either cold or hot. All the other vinaigrettes have the moniker "French dressing." A Google Books search reveals an undated but aptly titled "Random Recipes," which seems to date from approximately mid-century, and which includes a recipe for Tomato French Dressing calling for the use of Campbell's tomato soup, and "Florida 'French Dressing'," containing minute amounts of paprika, but generous citrus juices and a hint of sugar. So maybe people were making their own sweetly orange French dressing at home after all?

There is some debate as to who actually "invented" the orange stuff, but while Teresa Marzetti may have helped popularize it, the general consensus is the Milani brand, which started selling its orange take in 1938 (or the 1920s, depending who you ask - I haven't found a definitive answer one way or the other), was the first to commercially produce it. Confusingly, the official Milani name for their dressing is "1890 French Dressing." The internet has revealed no clues as to whether or not the recipe actually dates back that far, but a 1947 New York Times article claims "On the shelves at Gimbels you'll find 1890 French dressing, manufactured by Louis Milani Foods. It is made, the company says, according to a recipe that originated in Paris at that time and was brought to this country after the fall of France. This slightly sweet preparation, which contains a generous amount of tomatoes, costs 29 cents for eight ounces." This seems like a marketing ploy rather than the truth, but who knows for sure?

In 1925, the Kraft Cheese Company did sign a contract with the Milani Company to become their exclusive distributor. At least, that's what a snippet view of 1928 New York Stock Exchange listing statements tells me. As early as 1931 Kraft was manufacturing French Dressing under their name, and by the 1940s it had also used the Miracle Whip brand name to create Miracle French Dressing - which had just a "leetle" hint of garlic.

One snippet reference in the 1934 edition of "The Glass Packer" notes, "Differing from Kraft French Dressing, Miracle French is a thin dressing in which the oil and vinegar separate in the bottle, and which must be shaken immediately before using." Miracle French was contrasted often in advertising with classic Kraft French as being zestier, which may have led to the development in the 1960s of Kraft's Catalina dressing, a thinner, spicier, orange-er French dressing.

In fact, as featured in this undated magazine advertisement, Kraft at one point had several varieties of French Dressing including actual vinaigrettes like "Oil & Vinegar," and "Kraft Italian" alongside Catalina, Miracle French, Casino, Creamy Kraft French, and Low Calorie dressing, which also looks like French dressing. What you may notice is that the "Creamy Kraft French" looks suspiciously like most of the gloppy orange stuff you see on shelves today, and which generally doesn't resemble a thin, runny, paprika/tomato-red dressing that dominates the rest of this lineup.

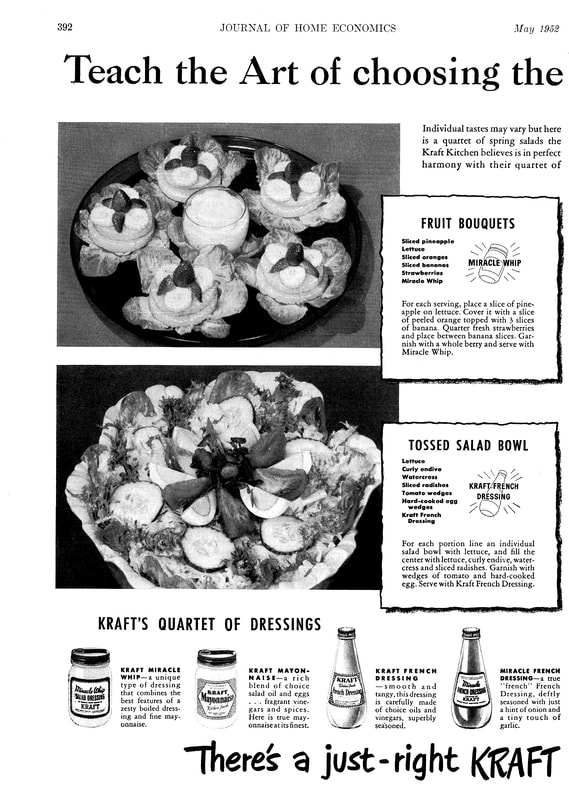

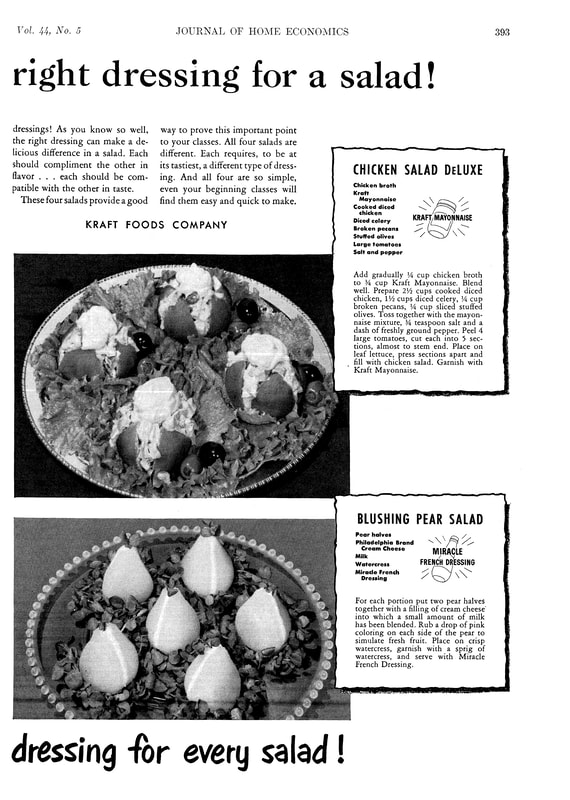

"Spicy" Catalina dressing was likely introduced sometime around 1960 (although the name wasn't trademarked until 1962). Kraft Casino dressing (even more garlicky) was trademarked for both cheese and French dressing in 1951, but by the 1970s appears to have left the lineup. Here are a few fun advertisements that compare some of the Kraft French dressings:

Of course by the 1950s other dressing manufacturers besides Kraft were getting in on the salad dressing game, including modern holdouts like:

Although many people in the United States grew up eating the creamy orange version of French Dressing, it's mostly vilified today (aside from a few enthusiasts). Which is too bad. As a dyed-in-the-wool ranch lover (hello, Midwestern upbringing - have you tried ranch on pizza?), I try not to judge peoples' food preferences. And I have to admit that while I've come to enjoy homemade Thousand Island dressing, I can't say that I've ever actually had the orange French! Of any stripe, creamy, spicy, or otherwise. I'm much more likely to use homemade vinaigrette from everything from lentil, bean, and potato salads to leafy greens. So to that end, let's close with a little poll. Now that you know the history of French Dressing, do you have a favorite? Tell us why in the comments!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

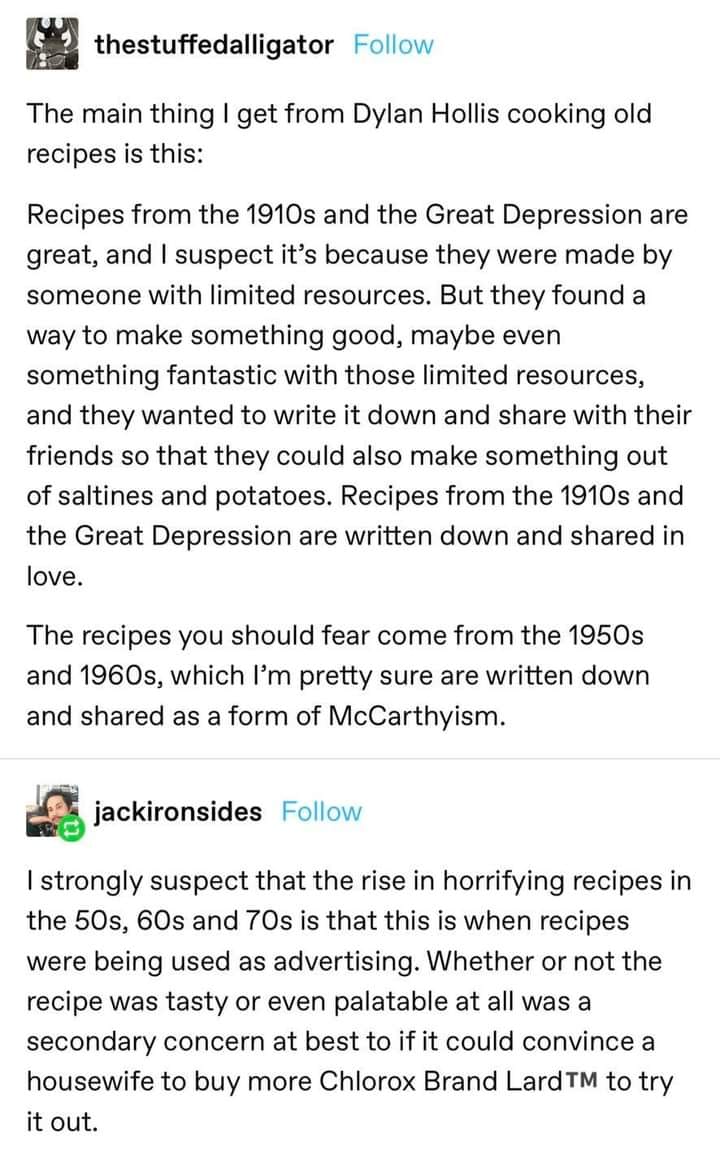

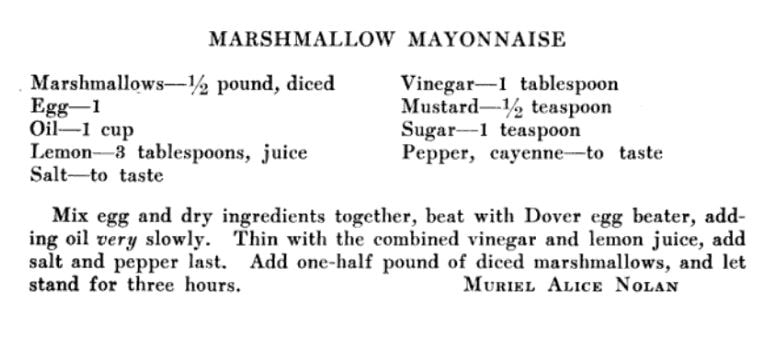

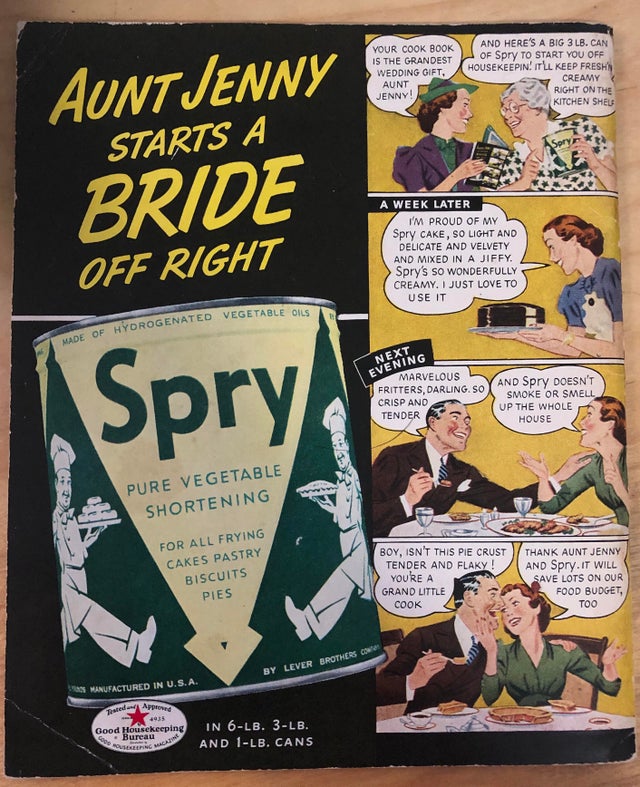

Well friends, I said I was contemplating a part two to last week's examination of 1950s food, and this meme kept popping up on my socials, so here we are again! This one isn't quite as inflammatory, and no fun illustration to catch your eye, but it makes a similar claim nonetheless. Here's the original text: The main thing I get from Dylan Hollis cooking old recipes is this: If you haven't seen any of Dylan Hollis' TikTok videos, I recommend them! He's hilarious. Not a food historian, but he cooks historic recipes and taste tests them. Some are horrific, but most are delicious - and while Dylan's reactions are 99% of the fun, his shock when things are actually tasty, while hilarious, does grate a little sometimes. Yes, people in the past really did know what they were doing! The meme claims that the food of the 1910s and the Great Depression were better than the 1950s, and were made with love, working with limited ingredients, whereas 1950s recipes were made to sell products during the McCarthy era. And while those ideas aren't necessarily wrong, they're definitely not the whole story. The time period of 1900 to 1950 is my favorite time period for cookbooks. They usually have decent instructions with things like measurements and oven temperatures, but are still from scratch. USUALLY being the key word there. Because starting in the 1870s, corporate food brands started publishing cookbooklets to sell their products. One of the earliest adopters of this sales tactic? Cottolene brand shortening. Not exactly lard, but pretty darn close! A lot of the corporate cookbooks and cookbooklets of the late 19th and early 20th century were primarily for ingredients. Different brands of flavorings and spices, baking powder, flour, shortening or lard, etc. were the main branded food products at the time. A lot of major food companies today started out as flour companies, including General Mills. So the cookbooks were largely normal scratch recipes that just recommended the cook or baker use the branded ingredients, but it was easy to substitute whatever you had on hand. And then, we started to get corporate food products like Campbell's canned soups, and Libby's canned corned beef, and powdered Knox gelatine and Jell-O, and other foods that were closer to finished foods already. You can only eat so much soup in a week. So how was Campbell's to get people to eat more of it? In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we had more and more women graduating from food and nutrition schools and college programs. Domestic scientists and expert cooks and home economists happily filled the role of cookbook authors and test kitchen managers for food corporations. Which is how we got things like tomato soup spice cake (Dylan Hollis does a recipe from the 1950s, but it was actually invented in the 1920s!), cream of whatever soup casseroles, and marshmallow mayonnaise. While tomato soup spice cake is probably delicious (at least, Dylan Hollis thinks it is!), and cream of whatever soup is a lot easier than white sauce, I'm not sure about the marshmallow mayonnaise, but the cookbook says to serve it with fruit salad, so maybe it is? Who am I to judge? The point being, by the 1910s, there were plenty of marketing cookbooks and advertisements with recipes for processed foods for housewives to choose from. And while home economists were cranking out recipes that were sometimes smash hits and sometimes abject failures, there was a bit of a storm brewing in households around the country. Mainly, the "servant problem." For most of the 19th century, middle and upper-middle class families had at least one household servant (or enslaved person, prior to the Civil War) who did the bulk of the heaviest household labor. Middle class women and their daughters did household work too, but were generally spared things like scouring pots and scrubbing floors and hauling water and coal. But at the turn of the 20th century, we started to get pink collar jobs - being a shop girl or secretary or teacher or nurse was preferable for many women to the 24/6.5 schedules of being in service. Rural families usually had lots of children to help with agricultural labor, but in a family of 6 or 10, the older girls always helped care for the younger children and everyone did household chores. As families shrunk and household servants became harder to find and more expensive, more and more women had to do with less and less help at home. At the same time, education levels for women were rising. Girls stayed in school beyond the elementary level and attended high school and college in larger and larger numbers. Many parents also wanted better lives for their children than they had, and wanted to spare girls the drudgery of household labor. Upper and upper-middle class girls, in particular, had been raised in households with servants and mothers who spared them all but the basics of running a household. So when they married, all of a sudden girls with college educations had to figure out household budgets and weekly grocery shopping and cooking on their own, without many skills or resources to help them. Enter the ad man and the home economist. Swearing to save the clueless young bride from a lifetime of drudgery, while still pleasing her husband, all sorts of companies targeted young, inexperienced women just starting their households, but none perhaps as diligently as Spry, which manufactured first lard and later shortening (there's that lard reference again!). Aunt Jenny was the fictional grandmotherly character who knew just everything and would teach it all to her clueless niece. And of course, the secret was always a giant can of Spry. While Spry cookbooklets joined the legion of competitors, it was their cartoon-style print ads and extensive radio shows and advertisements that helped sway millions of American women to the Spry way of life. Is it any wonder that women who married in the 1930s and '40s raised children in the 1950s on corporate foods? Untrained, without the household help of their mothers and grandmothers, and with high expectations for home cleanliness and cooking three meals a day, 364 days a year would be enough to drive anyone into the arms of kindly home economists and fictional characters like Aunt Jenny, Mary Lee Taylor, Betty Crocker, and others. Recipes as advertisements for corporate foods did NOT start in the 1950s by any means. But the meme is somewhat correct in that scratch cooking was more prevalent in the Great Depression in particular, largely because at the time industrial foods were still more expensive than cooking from scratch, and because women who were adults in the 1930s were more likely to have been born into households that still taught them something about cooking and household management. And although the balance of population in the United States tipped from rural to urban in the 1920s, we still had a huge population of people primarily involved in agriculture, meaning families were larger (my mom's parents, born to farmers in the 1930s, came from families of 9 and 10 children, respectively), so women had more household help. Rural areas were also slower to adopt new fashions, including fashionable food, and often had less access to industrial goods of all sorts, including processed foods. Rural families were also much more likely to grow and preserve the bulk of their own food, well into the 1970s, than the rest of America. If you had land and free labor, it was certainly cheaper than buying commercially canned goods. If your grandmother grew up in a rural area during the Great Depression, like mine did, she probably learned how to cook from scratch. But by the 1950s, she was raising kids on her own, and maybe had a career of her own, or was supporting her husband's career, which meant less time to cook from scratch as she cared for her own children and a house with higher standards of cleanliness and fashion than her mother's with a lot less help. At the same time, in the 1950s, the general consensus was that industrial foods were the wave of the future - they were boons to help a busy housewife, not things to be scorned and rejected. And as incomes rose, it was much easier to purchase foods than doing your own home preserving. And while the Great Depression did result in a lot of creative cooks (banana bread, for instance), I find the mention in the original meme of Saltines ironic. Although Saltines and cracker companies like Ritz didn't invent cracker-based mock apple pie (that dates back to the 1850s, believe it or not), they sure hopped right on that bandwagon and used it as a selling point. Necessity is the mother of invention. But rising incomes are the mother of convenience. And while McCarthyism probably did prevent the spread of some delicious and interesting foodways through its xenophobia and rigid conformity, the road to corporate convenience foods was a long one. They didn't appear overnight once the calendar ticked over from 1949 to 1950. Indeed, scratch cooking and baking continued well into the 1950s, and many of the foods we associate with the 1950s (Cool Whip, anyone?) weren't actually invented until the 1960s. For instance, the Pillsbury Bake-Off baking contest didn't start until 1949, and while modern incarnations of the contest are usually dominated by mutated versions of whatever convenience food Pillsbury has cooked up (usually crescent rolls or cinnamon rolls or canned biscuits), the original contest was meant to promote Pillsbury flour, so the recipes are all from scratch. And looking at my food historian library shelves, the 1950s section has plenty of community cookbooks filled with can-of-this, box-of-that recipes, and advertising cookbooklets galore, but there are also cookbooks like The Magic in Herbs (first printed in 1941 but on its seventh printing by my 1950 copy) and The Peasant Cookbook (1955, and my copy was from the library of the Ladies' Home Journal!), and Whole Grain Cookery (1951) and those community cookbooks always had scratch recipes in them, too. And my 1930s section? I have more corporate cookbooklets from the 1930s than any other era! Like most of history, individual decades might be changed and marked by big events, but history is complicated. In the Progressive Era we had brutal strikes and food riots, but we also had Gibson Girls and Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. During the Great Depression we had the Dust Bowl and migrant workers, but we also had the glamour of Hollywood. And yes, in the 1950s we had McCarthyism (and sexism and racism) and processed food, but we also had folks like James Beard and Julia Child and plenty of scratch cooking. So let's stop stereotyping decades and accept them for what they are - complicated, messy, and fascinating time periods with both good food and bad. And the next time you see a corporate food cookbook from the 1950s - give it a gander. You might be surprised by what you find inside. There are good recipes in just about every cookbook, if you take the time to look. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! There's this weird trend in modern America where we love to mock the foods of the 1950s (and, to a lesser extent, the 1960s and '70s). Everyone from James Lileks (here and here) to Buzzfeed-style listicles to internet memelords have weighed in on how terrible food was in the 1950s. But was it? Was it really? Or are we just expressing bias (conscious or not) about foods we haven't tried and don't understand? I have seen this meme all over my social feeds lately. Including, regrettably, in some food history and food studies groups. Some clever memer stole an image from Midcentury Menu (which is a delightful blog, please check out Ruth's work) and added their own commentary. The author of the meme is unclear, but it appears to have been posted about a week ago. Whenever I challenge the idea that maybe 1950s foods aren't nearly as bad as we think they are, I often get accused of engaging in nostalgia (spoiler alert, I was born in the 1980s) or romanticizing the past, usually accompanied by an assertion that these foods are "objectively" bad. But I can't help but thinking of how our concepts of disgust are much more a product of the society and time period we were brought up in, than anything resembling objectivity. The New York Times Magazine just published an article about the science of disgust earlier this week, but what I find interesting about the article is how many of the examples centered on food, and yet how little food is actually discussed. Indeed, almost all of the science of disgust seems focused entirely on evolutionary factors, such as protecting us from spoiled foods, from acquiring diseases from bodily fluids and corpses, or from weakening our gene pool through incest. Very few people outside of the food world discuss the cultural reasons behind disgust that have nothing to do with biology and everything to do with cultural, racial, religious, and ethnic factors. Earlier this year The New Yorker published a piece by Jiayang Fan on the controversial Disgusting Food Museum in Malmo, Sweden. The museum "collects" foods from around the world that its founders deem disgusting, with much controversy. Although the museum includes European foods like stinky fermented fish and salty licorice, it also includes many foods from non-Western societies. Many argue it reinforces cultural prejudices. Fan does not make specific value judgements about the museum itself, but does share her personal experiences as a Chinese person in the United States. I found the following passage in particular to be illuminating for Western audiences. Even so, disgust did not leave a lasting mark on my psyche until 1992, when, at the age of eight, on a flight to America with my mother, I was served the first non-Chinese meal of my life. In a tinfoil-covered tray was what looked like a pile of dumplings, except that they were square. I picked one up and took a bite, expecting it to be filled with meat, and discovered a gooey, creamy substance inside. Surely this was a dessert. Why else would the squares be swimming in a thick white sauce? I was grossed out, but ate the whole meal, because I had never been permitted to do otherwise. For weeks afterward, the taste festered in my thoughts, goading my gag reflex. Years later, I learned that those curious squares were called cheese ravioli. Asian foodways, especially Chinese foods, are often at the top of the "disgusting" lists - a combination of racism and deliberate misunderstanding of ancient foodways. For instance, lots of ancient Roman foods were also "gross," but are rarely consumed today, so modern Italians don't get the same level of derision. Many people like to argue that foods they find disgusting are "objectively" bad - but these same folks probably don't bat an eye at moldy congealed milk (blue cheese), partially rotten cucumbers (fermented dill pickles), or 30 day-old meat (dry aged steak). It's all about upbringing and perspective - something that folks who fail to recognize their own personal bias don't seem to get. And certainly, everyone is entitled to their own personal feelings on particular foods. For instance, despite several attempts, I can't stand the flavor of beets. But I know that, because I've tried them. "Disgusting" foods are often vilified by people who have never actually tried them. While immigrant foodways have often been the target of othering through disgust in the United States (see: Progressive Era Americanization efforts), for some reason the Whitest, most capitalistic of the historic American foodways - the 1950s - is the target of the same treatment today. Perhaps it is that in our modern era we have vilified processed corporate foods. And while I'm the first person to advocate for scratch cooking and home gardens and farmer's markets and all that jazz, there's much more seething under the surface of this than just a general dislike of gelatin. When processed foods first began to emerge in the late 19th century with the popularization of canned goods, they democratized foods like gelatin, beef consommé, pureed cream soups, and out-of-season fruits and vegetables that had previously been accessible only to the wealthy. Suddenly, ordinary people could afford to have salmon and English peas and Queen Anne cherries year-round - not just the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts of the world. After the austerity of the Great Depression and the Second World, the world seemed poised to combine those lingering ideas of what the wealthy ate with all the convenience modern technology could offer. Certainly, as some have argued, corporate marketing and test kitchens played a major role in shaping what Americans ate. But just because it was invented for an advertisement doesn't mean Americans didn't eat it on a regular basis. By the 1970s, many of those miracle technologies such as canning, freezing, dehydrating, reconstituting, etc. had become hallmarks of affordable - and therefore poor - foodways. "Government cheese," canned tuna, white bread, canned vegetables, mayonnaise, boxed cake and biscuit mixes, and yes, gelatin and Cool Whip were what poor people ate. Wealthier people ate "real" food - a trend that continues today. Disdain for poor people and their food seems universal, but even today, certain poor people have their foodways elevated over others (namely, pre-Second World War European peasants and select "foreign" street food purveyors). People living predominantly subsistence agricultural lives are seen as "authentic," while their urban counterparts, who consume processed foods by choice or by circumstance, are "selling out." But even "authenticity" only goes so far with some people. And even when foodies pride themselves on "bravely" eating chicken feet and fermented fish and other foods many would deem "disgusting," there's still an element of othering and disdain at play, a loud proclamation of worldliness and coolness at eating what their peers might avoid, that has little to do with actually understanding the culture behind the food. The food of the 1950s, once the clean, efficient, technologically advanced wave of the future quickly became the purview of the poor and working class. And while mid-century foodies like MFK Fisher and James Beard and (to a lesser extent) Julia Child descried processed foods and hailed European cuisines, peasant and "haute" alike, the vast majority of ordinary people ate ordinary, processed foods, and tried recipes dreamed up by home economists in corporate test kitchens. And within two decades, once the futurism wore off and the affordability factor set in, it became perfectly acceptable, cool even, to deride and mock those foodways. Which brings me back to the tuna on waffles. Canned tuna in cream of mushroom soup on top of hot, crisp waffles (probably NOT frozen, as frozen waffles weren't invented until 1953) is not something most of us are likely to eat on a regular basis today. However, it is hearkening back to a much older recipe: creamed chicken on waffles, which dates back to the Colonial period in America. Although the history of creamed chicken on waffles isn't crystal clear, this dish is clearly what Campbell's was emulating with their recipe. But what's the disgust factor? How is creamed tuna on waffles different from a tuna melt? Creamed chicken and biscuits? Fried chicken and waffles? Perhaps it is because today we associate waffles exclusively with sweet breakfast foods, so the idea of savory waffles is baffling. But they've only been used that way for a fraction of their history, for most of which they were used much more like biscuits or bread than a dessert. Or perhaps it's the tuna? Despite being hugely popular in the 1950s, tuna has fallen out of favor nationwide. Concerns about mercury, dolphins, and its association with poverty have helped dethrone tuna. But in the 1950s, it was a relatively new, and popular food. Today, it's a "smelly" fish associated with cafeterias and diners and cheap meals like tuna noodle casserole. Maybe it's the canned cream of mushroom soup? Cream of whatever soups remain a popular casserole (hotdish, for my fellow Midwesterners) ingredient even today, and the ability to replace the more labor-intensive white sauce with a canned good has helped many a housewife. Today, canned soups are vilified as laden with sodium and, for the creamy ones, fat. But canned goods have also been scorned as poverty food, with modern foodies touting scratch made sauces and fresh vegetables as healthier and better tasting. In the context of the 1950s, fresh vegetables were not always widely available as they are today, so canned and frozen vegetables took the drudgery out of canning your own or going without. In fact, our modern food system of fresh fruits and vegetables is propped up by agricultural chemicals, cheap oil, watering desert areas, and outsourcing agricultural labor to migrant workers or farms in the global south. Something many foodies like to conveniently overlook. My ultimate point isn't that people shouldn't reject processed foods in favor of scratch cooking. Indeed, I think that anyone who can afford to cook from scratch, should. But there's the rub, isn't it? Afford to. Because as much as homesteaders and bloggers and foodies like to proclaim that cooking from scratch is cheaper and healthier, it requires several ingredients they take for granted that aren't always available to everyone - a kitchen with working appliances, adequate cooking utensils, access to a grocery store and the means to transport fresh foods (fresh fruits and vegetables are HEAVY), the skills to know how to cook from scratch effectively and efficiently, and most importantly, TIME. As the old adage goes, you can have good, fast, and cheap, but never all three at once. Good and fast is expensive, good and cheap takes time, and fast and cheap is usually not very good. And when you're working multiple jobs to make ends meet, getting decent-tasting food on the table in a timely manner is more important than worrying about cooking from scratch. Those were the same concerns many working class people in the 1950s had, too. Even though the stereotypical White 1950s housewife had plenty of time to cook from scratch, plenty of women, especially women of color, worked outside the home in the 1950s. And mid-century Americans spent a far higher percentage of their income on food than they do today. And while fast food was around in the 1950s, it wasn't particularly cheap. For most Americans, it was an occasional treat, and restaurant eating in general was reserved for special occasions. Casual family dining as we know it today didn't exist. So that meant the typical housewife, wage working or not, had to cook 2-3 meals a day, nearly 365 days a year. Is it any wonder they turned to processed foods where most of the work was done for them? Maybe I've got a little personal bias of my own - after all I was raised in the land of tater tot hotdish and salads made with Cool Whip (That Midwestern Mom gets me). Foods that are often vilified by (frankly snobbish) coastal foodies, but that are "objectively" quite delicious. I like melty American cheese on my burger and grilled cheese as much as I enjoy making a scratch gorgonzola cream sauce. Fruit salad made with Cool Whip is a fun holiday treat. And while I prefer to make my own macaroni and cheese from scratch, I'd never mock or turn up my nose if someone offered me Kraft dinner. I think the driving force behind this pet peeve of mine is the idea that anyone can be the arbiter of taste (or disgust) when it comes to someone else's foodways. As my mom always used to say, "How do you know you don't like it if you don't try it?" Everyone's food history deserves respect and understanding. So let's give up the mean girl attitudes about foods we're not familiar with and let go of the guilt about liking the foods we like, be they 1950s processed foods or 500 year old family recipes. And the next time someone talks about how "gross" or "disgusting" a food is, or goes "Ewwww!" when presented with something new, give them a gimlet eye, ask them if they've ever had the dish, and then ask, "Who are you to judge?" The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

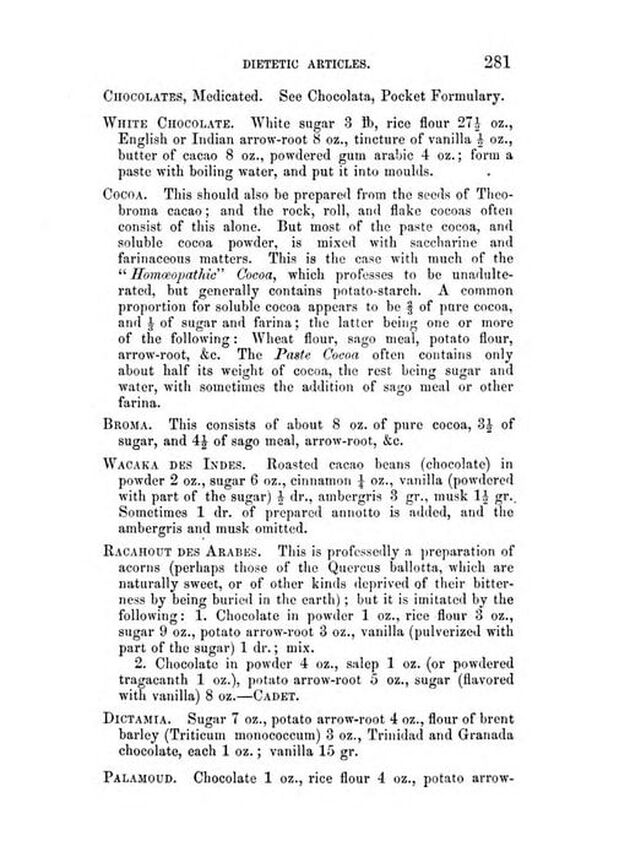

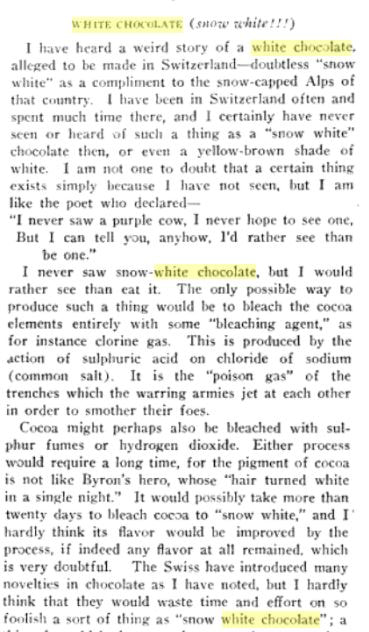

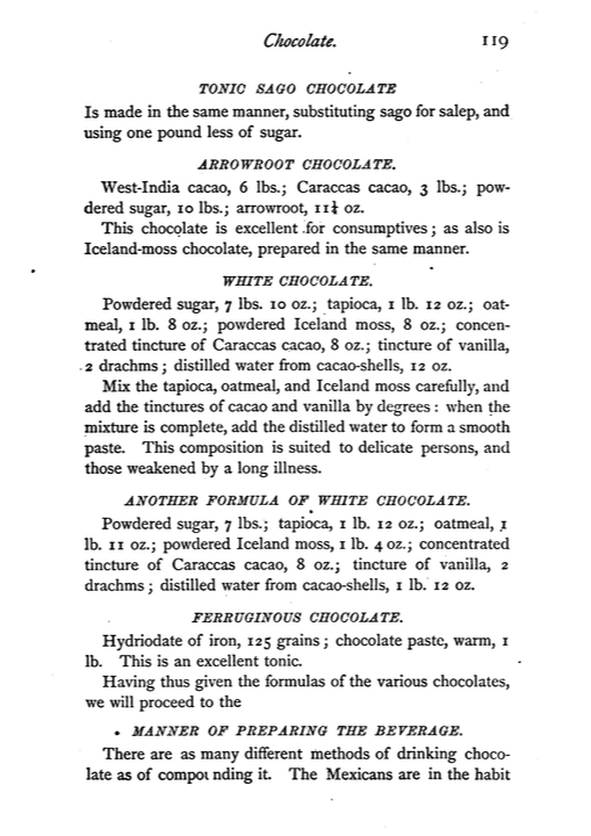

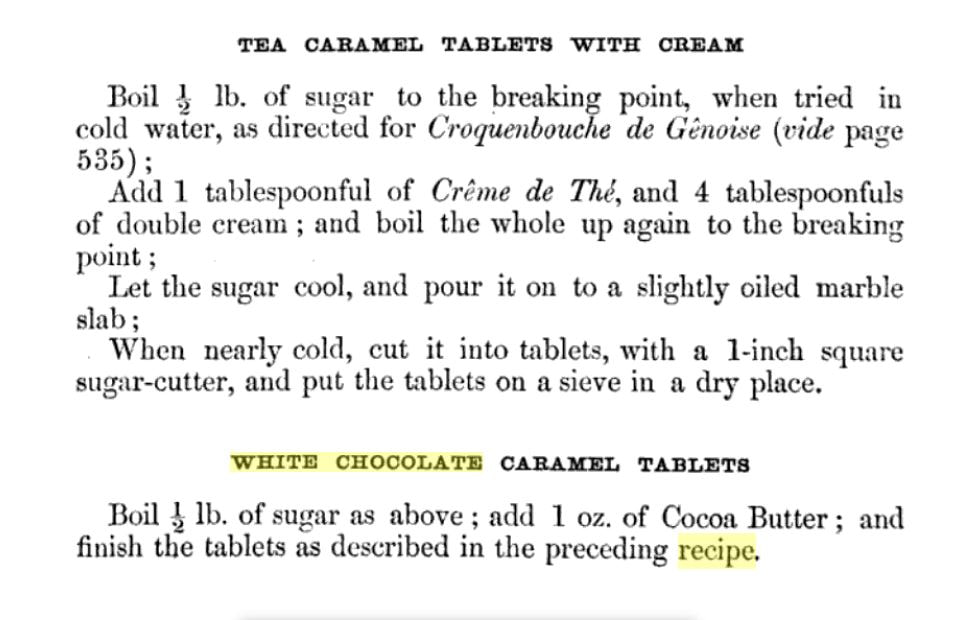

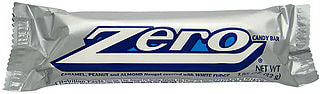

This month has been all about pumpkins and Thanksgiving, chez Food Historian. I have done my "As American as Pumpkin Pie" talk several times in the last few weeks. If you missed it, you can catch a recording, and the recipe for Lydia Maria Child's 1832 Pumpkin Pie here. I've also been doing a lot of media interviews about Thanksgiving, including for National Geographic and USA Today. And of course, my goal is always to try to debunk the mythology of the 19th century concept of Thanksgiving, which is rooted, wittingly or not, in white supremacy, Christian supremacy, and the supremacy of New England culture. Food historian Andrew F. Smith in the Association for the Study of Food and Culture Facebook page posted earlier this week about Thanksgiving. He writes: Sorry to report that the "Pilgrims" had nothing to do with Thanksgiving; it's all a made up story. Days of thanksgiving were frequently celebrated in colonial America– particularly in New England. These thanksgivings were usually declared in response to local events, such as surviving a long trip, military victories, good harvests, or providential rainfalls. These were solemn religious occasions spent in prayer, and little evidence has surfaced suggesting that a formal meal was part of the thanksgiving observance: only two records mention food, and they’re unusual. Thanksgiving dinners were well established by the American War for Independence (1776-1783). To celebrate the victory at Saratoga in 1777, the Continental Congress declared a day of thanksgiving. Joseph Plumb Martin, a soldier, noted in his journal that for this celebration, “Each man was given half a gill of rice and a tablespoonful of vinegar.” More sumptuous fare appeared in 1779 descriptions of thanksgiving meals. In one, a goose was served; in the other, venison, goose and pigeons were served along with a plethora of side dishes and deserts. In New England, the thanksgiving dinner became particularly significant event by the late eighteenth century. A participant in a 1784 thanksgiving meal in Norwich, Connecticut, proclaimed: “What a sight of pigs and geese and turkeys and fowls and sheep must be slaughtered to gratify the voraciousness of a single day.” William Bentley, the pastor of the East Church in Salem, Massachusetts, reported in 1806, that, “A Thanksgiving is not complete without a turkey. It is rare to find any other dishes but such as turkies & fowls afford before the pastry on such days & puddings are much less used than formerly.” Bentley’s description suggests that a two-course meal —the first consisting of turkey and perhaps other meat dishes, and the second, of dessert. This pattern was common during the early nineteenth century and these traditions were long maintained. The first association between the Pilgrims and thanksgiving appeared in 1841, when Alexander Young published a copy of a letter written by Edward Winslow, dated December 11, 1621, to a friend in England. It described a three-day fall event, the dates of which were not cited. In this letter, Winslow writes: Our harvest being gotten in, our Governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a more special manner re[j]oice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours. They four in one day k[i]lled as much fowl as, with a little help besides, served the Company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king, Massasoit with some 90 men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted. And they went out and killed five deer which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our Governor and upon the Captain and others. You will note that there is NO statement that this was a “thanksgiving.” In a footnote to the 1841 reprint of the letter, Alexander Young claimed that the event described by Winslow “was the first thanksgiving, the harvest festival of New England. On this occasion they no doubt feasted on the wild turkey as well as venison.” However, Winslow did not use the word thanksgiving to describe this or any other event in the fall of 1621. The Puritans made no subsequent mention of this event and it was not remembered or observed in later years by the Pilgrims or Puritans. The feast described by Winslow makes no mention of prayer and it does include many secular elements: the Puritans would not have considered this a thanksgiving. However, the idea that the 1621 event at Plimoth Plantation was the “First Thanksgiving” was picked up by others, and by the mid-nineteenth century it was generally believed in New England that the Pilgrims had invented thanksgiving in America. Of course, Jamestown, settled in 1607, observed many days of thanksgiving years before the Pilgrims landed at Plimoth Plantation, and a plaque in Jamestown marks the purported site of the real “First Thanksgiving,” but factual knowledge was unable to stop the fakelore of the Pilgrim connection with thanksgiving from spreading. The driving force behind making thanksgiving a national holiday in the United States was Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book. Hale commenced her campaign to create a national thanksgiving holiday in 1846. For the next seventeen years, she wrote annually to members of Congress, prominent individuals, and the governors of every state and territory, requesting each to proclaim a common thanksgiving day. In an age before word processors, typewriters, or mass media, this was a difficult campaign to wage. Hale believed that a thanksgiving holiday would help bind the United States together. She came close to success in 1859 when thirty states and three territories observed thanksgiving on the third Thursday of November. During the Civil War, she was unable to communicate with many Southern states, so rather then request each state, she approach President Lincoln, asking for thanksgiving to be designated a national holiday. A few months after the North’s military victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863, Hale achieved success: Lincoln declared the last Thursday in November a national day of thanksgiving, and the holiday has been celebrate ever since in the United States. Smith outlines a good argument. Days of thanksgiving were common throughout early American history, could be declared at any time of year, and were usually not associated with feasting. When they were, it was often after the fall harvest, as the "original" 1621 version. Harvest feasts are very English, so it makes sense that the Separatists (what the Pilgrims were actually called) would celebrate a successful harvest after so devastating a winter with a feast. Harvest Home, or Ingathering, is an ancient tradition in the British Isles. It also makes sense that traditionally British foodways, such as eating sour fruits with wild game birds (turkey and cranberry sauce, anyone?), pies, gravy, and mashed root vegetables, would make their way onto New England harvest dinner tables. But days of thanksgiving were also declared for far darker reasons, including the "victory" in May, 1637 known today as the Pequot Massacre. The idea that our modern Thanksgiving stems from the celebration of that massacre is making the rounds of the internet lately, and while the connection is not direct, it's not as indirect as Snopes makes it out to be. Although, as Smith notes, Sarah Josepha Hale was the driving force behind our modern celebrations, whatever her intentions, the subtext of a distinctly British, New England tradition being sanctified by national authority to be celebrated throughout the land definitely fit with the driving cultural force of the 19th century - that White, Protestant, Yankee/English culture was superior to all others. It's no surprise that Thanksgiving finally became a national holiday in 1863 - the midst of the American Civil War. It's also no surprise that the mythology of the peaceful, helpful Indians was becoming part of our national conversation just as millions of Indigenous people were being forcibly removed from their lands and treaties violated right and left by the federal government notably during the "Plains Wars" of the mid and late 19th century. The Great Plains were some of the last areas of the United States to be colonized by Europeans, and so their Indigenous peoples were some of the last to be forcibly removed. It's also why most portrayals of Indians in Thanksgiving imagery depict them in the garb of Northern Plains Indians, which is substantially different from how Native peoples in the Northeast dressed historically.  This c. 1920 postcard is a classic example of how Thanksgiving mythology is perpetuated. A "Pilgrim" (They didn't dress like that either) sits with his gun over a freshly killed turkey. In the background, a giant pumpkin pie halos him. Behind the pumpkin, lurks a Native man dressed in Plains Indian clothing, his intentions unknown. By framing Indigenous people as complicit in their own destruction, Europeans could justify land theft (they weren't "using" it anyway!), genocide ("Kill the Indian, save the man"), and breaking countless treaties that legally have the same standing as the Constitution (you can't stop progress!). This is also why, for many Indigenous people, Thanksgiving is a day of mourning. A lot of people still celebrate Thanksgiving, and since the holiday in the modern era is much more focused on food and family, I think that's a good thing. However, it's important to understand what Thanksgiving myths are out there and why and to not perpetuated them. And it's equally important to support Indigenous people - emotionally, politically, and financially - as we celebrate. If you want to decolonize your Thanksgiving by educating yourself further, check out last year's post with a list of resources. The amazing film Gather is now available on Netflix and is fantastic. It would make a wonderful post-Thanksgiving-dinner watch with friends and family. Taking tangible actions is also important. You can support Indigenous food producers as you plan meals all year round, not just at Thanksgiving. You can support Indigenous people in their efforts to prevent oil and natural gas pipelines from violating treaties and polluting or utterly destroying the last vestiges of important ecological landscapes (which, newsflash, helps the whole planet). You can support the land back movement, which focuses on returning public lands acquired through treaty violations back to Indigenous ownership and/or stewardship. Especially since Indigenous people are generally much better at managing public lands than state and federal organizations. You can donate to legal aid organizations that help Indigenous people and tribes protect their individual and collective rights. And finally, you can push back against stereotypes of Indigenous people and Thanksgiving alike. Like my friend whose kindergartener came home with a Thanksgiving worksheet featuring stereotypical depictions of Pilgrims and Indians, who sent her teacher this amazing resource put together by the Native American Services department of Oklahoma City Public Schools on how to interpret Thanksgiving for children in a way that does not erase Indigenous people or perpetuate harmful myths. American history is messy. And that scares a lot of people. But history is complicated, and by better understanding it, we can better understand how we got to where we are today, and whether or not we should do anything to change or fix it. So this Thanksgiving, don't buy the same old stories you grew up with. They're myths for a reason, and we can challenge those reasons, because they suck. And if you don't want to make a Thanksgiving meal that puts New England foodways on a pedestal, feel free to skip the turkey, cranberry sauce, mashed root vegetables, pumpkin pie, and anything else you don't like but always feel obligated to eat. Make your own traditions, and celebrate your own, local harvest season with foods that reflect your family and your geography, without the guilt. Throw off the tyranny of "tradition." Life's too short for bad meals and bad history. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! I've done several talks now on the history of hot chocolate, and in the slide on white chocolate, someone expressed skepticism about the fact that Nestle invented white chocolate in the 1930s, although that is the current consensus on the internet. For the Nestle claim - sources differ. Some say they were manufacturing it as early as 1930. Others say the introduction of the Galak bar (known as the Milkybar in the UK) in 1936 was the first. Still others claim it wasn't really white chocolate until the 1948 Alpine White Bar, which contained almonds. This article indicates that Nestle's research into a coating for a children's vitamin was what birthed white chocolate. Still, it did seem a little unusual that white chocolate was developed so late (even though milk chocolate wasn't really a thing until the 1890s). So I did a little digging. There wasn't a whole lot out there. Most of the hits were for the words "white" and "chocolate" that just happened to be next to each other. I got excited by a reference to "white chocolate cake" from the 1870s, but that turned out to just be a white cake with chocolate frosting. But then, I started to find some interesting tidbits. White Chocolate Skepticism, 1916First, I found this little snippet from the December, 1916 issue International Confectioner, in an article entitled, "Chocolate a la Noisette, Part II" by T. B. McRobert. In this section, McRobert expresses deep skepticism that the Swiss have invented a "snow white chocolate," and speculates that they bleach it with chlorine gas, sulphur [sic] fumes, or hydrogen dioxide, rendering it nearly inedible. He ends the article with the comment, "Certainly we hear some queer and weird stories from Europe these war times, and perhaps the 'snow white' chocolate is one of these war time yarns. Certainly 'snow white' chocolate is never likely to be any howling success in this country, if in fact such a thing could ever be made here and comply with our food laws, which is more than doubtful." I did find another reference, several years later, in the 1923 Encyclopedia of Food by Artemis Ward. In the entry for "Cocoa-Butter," the main text is followed by this little intriguing sentence - "Swiss 'white chocolate' - apart from milk-chocolate types - is cocoa-butter sweetened either with sugar or with sweet chestnut-meal." A tantalizing snippet, unreadable in full (thanks, Google Books), indicates this description in Food Industries Manual published in 1931, on page 142: "White chocolate is manufactured from sugar, milk powder or condensed milk, and cocoa butter, and the flavour of chocolate is dependent upon the cocoa butter content. Accordingly a very strong cocoa butter is used in the manufacture ..." and that's all we get! Still, we're definitely pre-dating the Nestle story. And then there was this strange little find. Strange White Chocolate, 1870sThe dessert book: a complete manual from the best American and foreign authorities. With original economical recipes by a Boston lady, published in 1872. The strange recipes listed above, including two for "white chocolate" appear to be recipes designed more for confectioners or pharmacists than the home cook. Apparently designed for invalids or "delicate persons," the mixture of tapioca, oatmeal, and Iceland moss, flavored with "tinctures of cacao" and vanilla and mixed to a paste with "distilled water from cacao shells" is a far cry from mixing cocoa butter with sugar and milk solids, which is what we normally expect white chocolate to be. A similar recipe shows up in a druggist's recipe book from 1871.  A recipe for white chocolate calling for rice flour, cocoa butter, and gum arabic. From "The Druggist's General Receipt Book: Containing a Copious Veterinary Formulary : Numerous Recipes In Patent And Proprietary Medicines, Druggists' Nostrums, Etc. : Perfumery And Cosmetics : Beverages, Dietetic Articles, And Condiments : Trade Chemicals, Scientific Processes, And an Appendix of Useful Tables," by Henry Blakely and published in 1871. The Druggist's General Receipt Book: Containing a Copious Veterinary Formulary : Numerous Recipes In Patent And Proprietary Medicines, Druggists' Nostrums, Etc. : Perfumery And Cosmetics : Beverages, Dietetic Articles, And Condiments : Trade Chemicals, Scientific Processes, And an Appendix of Useful Tables by Henry Blakely and published in 1871, has a white chocolate recipe very similar to the one from "A Boston Lady." A mixture of white sugar, rice flour, arrowroot powder, vanilla, cocoa butter, and gum arabic, mixed with boiling water and molded, the resulting confection was likely a chewy one. White Chocolate Caramel Tablets, 1869The Royal Cookery Book (le Livre de Cuisine) by Jules Gouffé, Alphonse Gouffé (1869) revealed this interesting recipe: White chocolate caramel tablets were probably a type of chewy caramel, although it's difficult to say, given the recipe. Boiling sugar to the "breaking point" indicates possibly hard crack stage, in which case the tablets would be more like toffee or a hard caramel candy, rather than the soft white chocolate we are used to. The Broma Process, 1865Invented around 1865 by a worker at the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company, the broma process involves placing roasted cocoa beans in a bag just above room temperature to allow the cocoa butter to drip out. The remaining cocoa beans could then be processed into cocoa powder. But what to do the with cocoa butter? Much of it was processed back into bar chocolate, making it richer than 100% cacao. But I think the surplus of cocoa butter from the cocoa powder process meant that people were more interested in trying out different types of chocolate, like white chocolate. The timeline certainly matches the above findings of pre-1930s white chocolate. The Zero Bar, 1920One last candy was niggling at the back of my head - the Zero Bar, first introduced in around 1920 as the "Double Zero Bar" by the Hollywood Brands company, based in Minneapolis, MN. In 1934 the name was changed to "Zero Bar" and the wrappers have always brought to mind chilly temperatures, which was by design. A caramel nougat with almonds and enrobed in white fudge, this candy bar appears to be one of the earliest commercial applications of white chocolate. Today, the Zero Bar is still manufactured by the Hershey Company, although it can be difficult to find in stores. White Chocolate ConclusionsWhen all is said and done, Nestle still appears to be the first company to market solid white chocolate on a commercial scale, although the Zero Bar clearly predates the Milkybar/Galak by over ten years and the Alpine White (first introduced in 1948) by nearly twenty. I personally enjoy white chocolate, and the Zero bar was a childhood favorite of mine, although I know many people think white chocolate is inferior to the kind including the whole bean. But I'm not sure I enjoy it quite as much as these Alpine White television commercials would have us believe. Do you like white chocolate? Do you have a favorite candy bar? Let me know in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed