|

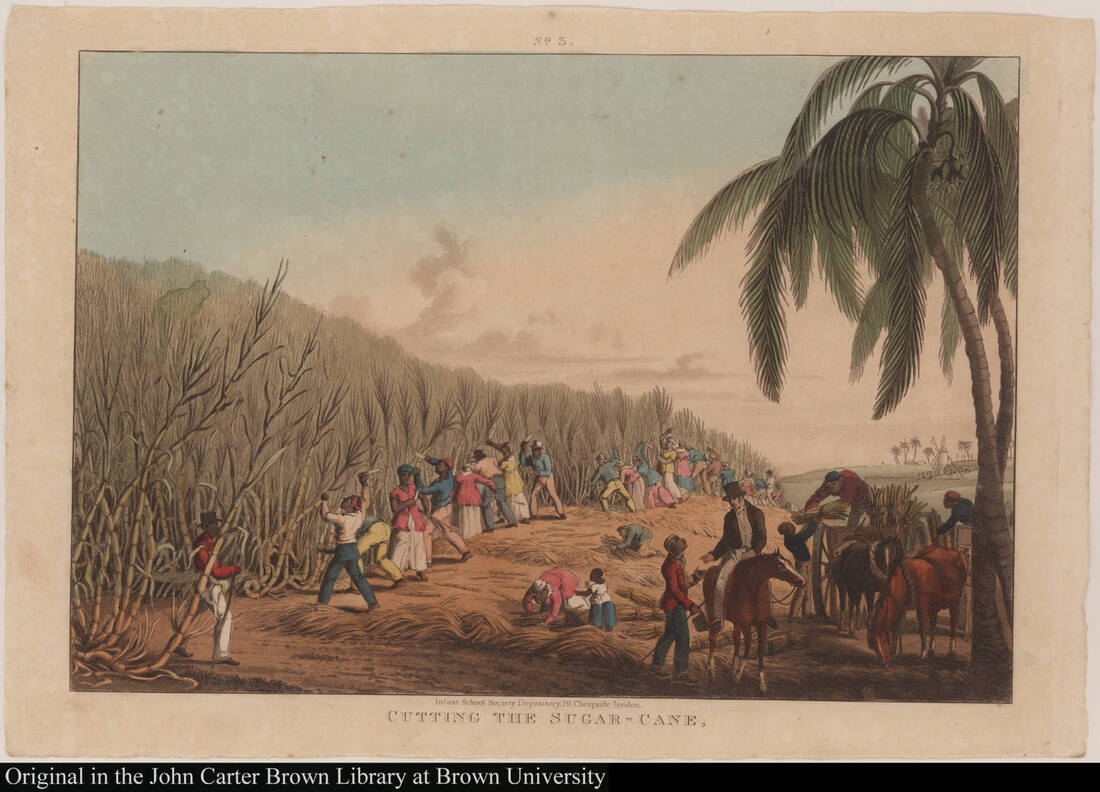

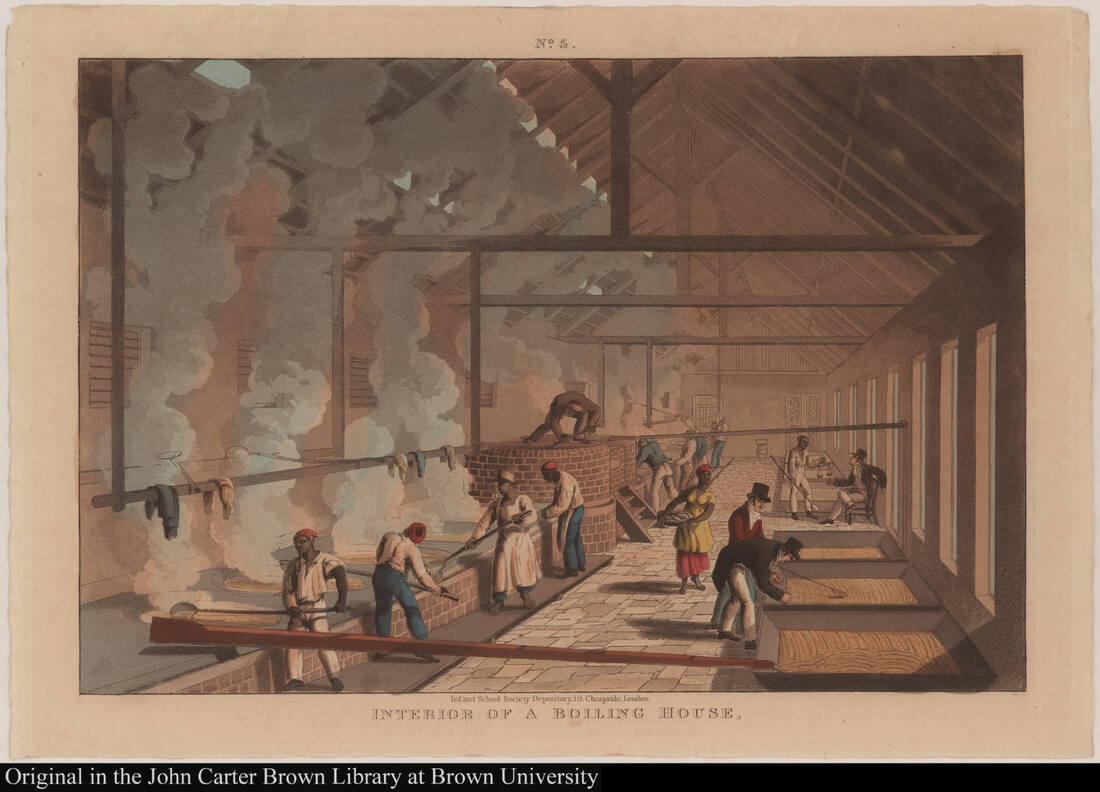

The United States owes enslaved people and their descendants a lot. White Americans don't like to admit that often, but we really do. And to me, nowhere is that more evident than in our modern food system. Today is Juneteenth - a celebration of the end of slavery in the United States. Not on the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, which was issued on January 1, 1863 and which LEGALLY freed all enslaved people in the country. No, it took until June 19, 1865 - fully two and a half years later, for the message (and the enforcement) to finally arrive in Texas with a group of Union soldiers. For although all enslaved people in the United States were deemed free in 1863, the Confederacy did not recognize that authority, and continued to enslave and exploit Black people until forced to do otherwise by armed Federal troops. So to celebrate Juneteenth, you can certainly look up recipes and plan a party. But I think it's equally important to recognize incredible contributions enslaved people made to our food system, and for Americans of all backgrounds to reckon with the truth that much of our modern foods are the direct result of violence and exploitation. At last night's Food History Happy Hour, viewer Cathy brought up that we learn a lot in school about the contributions of White immigrants, but not so much about the contributions of enslaved people. And that struck me as both very true and very sad. Because so much of what is considered American food is intimately connected to both West Africa and the enslaved people brought here against their wills. People who experienced incredible hardship still had the perseverance and fortitude not only to hold on to their foodways on the horrific voyage across the Atlantic, but to persist in keeping those foodways in the United States. Not all of the foods listed below came from West Africa, but all are a direct result of the enslavement of West Africans. Editor's note: The Food Historian is an Amazon affiliate. Any purchases you make through the book links below will help support blog posts like this! SugarWe can start with the biggest one. Before the enslavement of Africans in the Caribbean and American South, sugar was produced in India at great expense. By kidnapping people and forcing them into bondage, enormous sugar plantations were established by Europeans throughout the Caribbean, and later in American states like Louisiana. Sugar plantations were some of the most brutal of the plantation economy. The life expectancy of an enslaved person was very low, and some islands imported double or triple their populations per year in slaves, as many died faster than they could be replaced. Today, sugar is almost completely mechanized, but most of our modern foodways - sugary desserts in particular - are possible only through the massive effort to enslave millions of people for profit. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sugar became increasingly affordable, as sugar production mechanized. The cultivation of sugarcane remained incredibly labor-intensive. Sugarcane harvesting, for example, was not really mechanized in the American South until World War II. As an aside, I recently learned that the United States was active in the slave trade for decades after it was made illegal, and that the primary point of destination for American slave traders after kidnapping mostly children from West Africa was the sugar plantations of Cuba. This illegal trade continued until the 1860s. Further Reading:

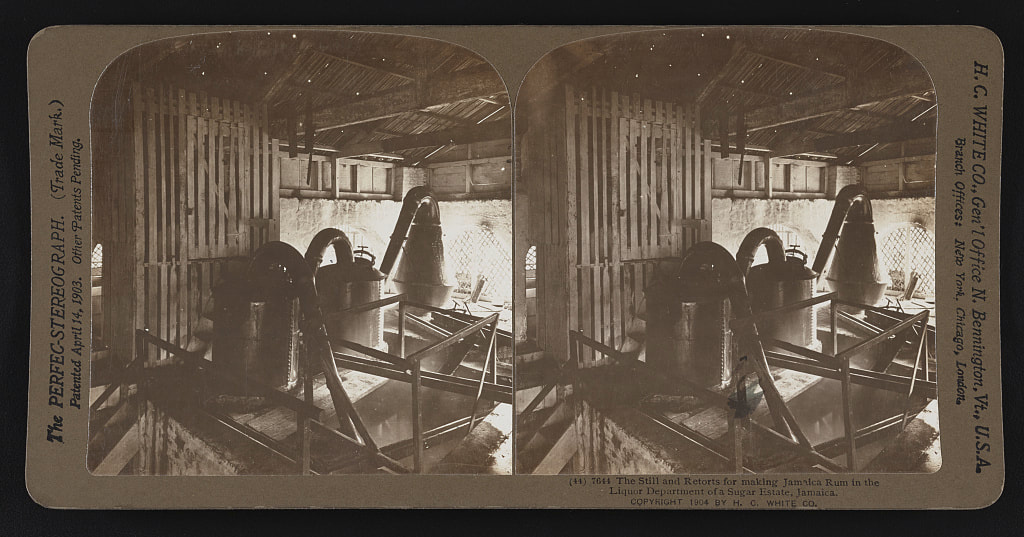

MolassesMolasses may make you think of baked beans, or gingerbread, or soft molasses cookies. But molasses is a byproduct of the sugar industry, and therefore slavery. Molasses, the cheapest sweetener, also was used in slave rations and was a major foodstuff among poor Whites throughout the United States until the mid-20th century. But although Molasses becomes intimately connected with New England and pioneer foodways, it has another important use... RumRum may make you think of pirates, but it was actually developed as a way to transform relatively worthless molasses into a high-value commodity. And while vicious pirates guzzled it by the gallon, it was also a huge economic engine not only in the Caribbean, but also in New England, where it was produced and used to purchase people and goods in West Africa as part of the slave trade. The irony being that a product largely produced by slaves (first in producing the molasses, and then often again in producing rum) was being used to purchase more slaves should not be lost on anyone. Further Reading:

Jack Daniels WhiskyWhile we're on the topic of alcohol and slavery, let's just take a moment to recognize that Jack Daniels was taught how to make whisky by Nathan "Nearest" Green, an enslaved man who used a charcoal filtering technique he learned to clean water in West Africa to filter the distilled alcohol. He was Jack Daniel's first master distiller, but only got credit more recently. Read the full story. RiceI know what you're thinking - Sarah, how are you going to relate RICE to slavery? Well, although today we consume a lot of rice developed in India and Japan, throughout the 19th century, Carolina Gold rice was king. Rice production in South Carolina dates back to the 18th century and plantation owners specifically sought out and captured West Africans skilled in rice agriculture and enslaved them to operate their rice plantations. The White plantation owners got obscenely rich on this scheme. Although Carolina Gold rice is no longer as prevalent in American food culture, it still made a huge impact on the economy of the South. Further Reading:

OkraNative to Ethiopia and cultivated in Africa as early as 12,000 years ago, okra was brought to North America by enslaved West Africans, the seeds braided in their hair. It went on to spread throughout the American South, influencing such dishes as regional varieties of gumbo and often served stewed with tomatoes or breaded and fried. Although not as widespread as some of the other foods on this list, okra still maintains a huge impact on American foodways. Further Reading:

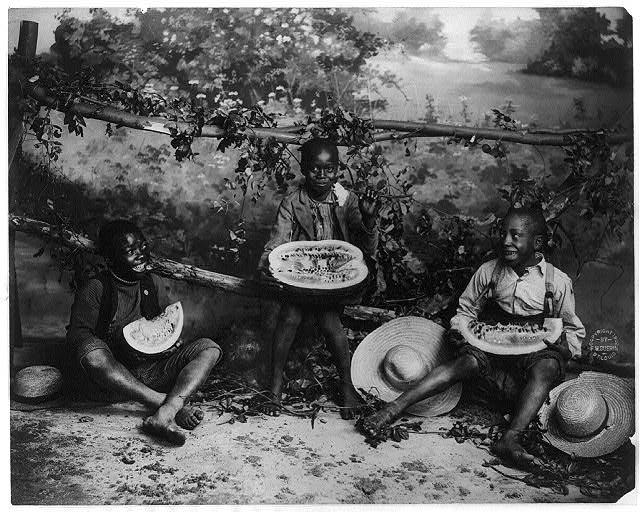

WatermelonDeveloped in the Kalahari desert of Africa, the watermelon was carefully bred by Indigenous Africans to go from a thick-rinded, rather tasteless melon to the sweet, juicy treat we know today. Although it did spread to Egypt and the Middle East, it was likely introduced to North America via the slave trade - either purchased by slave traders and kidnappers, or brought over by enslaved people themselves. The American stereotype of associating Black folks with watermelon as an insult is still around today. Further Reading:

Black Eyed PeasNative to West Africa, black eyed peas, sometimes called cowpeas, were brought to the Americas by enslaved Africans. In the U.S. they are most commonly known as the main ingredient in "Hoppin' John," a popular dish consumed on New Year's Day for good luck. Two stories about black eyed peas and luck have emerged over the years. The first is that when General Sherman made his way through Georgia, one of the only foods the Union Army did not take was black eyed peas, as they were considered cattle fodder in the North. The Confederate Army subsisted on this "slave food," an irony they clearly did not understand. The other story, and one I think far more likely, is that black eyed peas were one of the celebratory dishes consumed on January 1, 1863 - the day the Emancipation Proclamation became law. Further Reading:

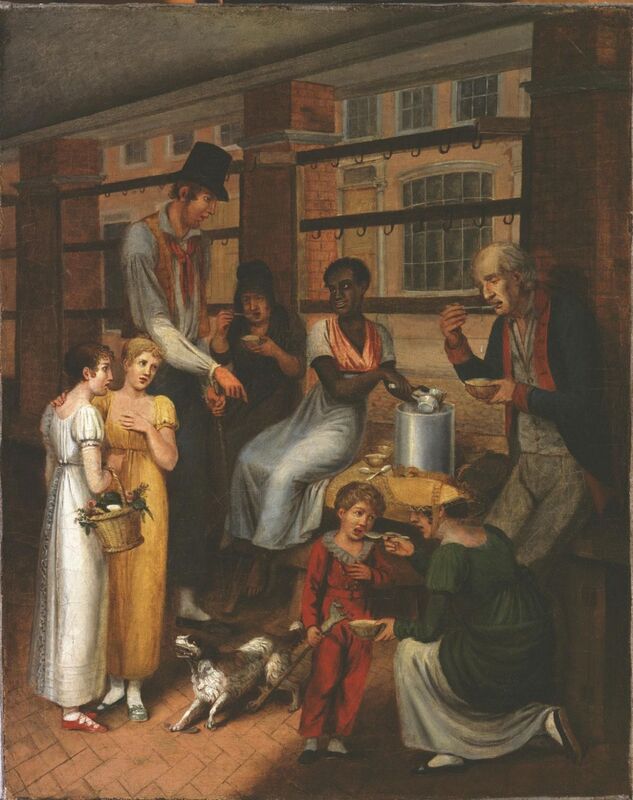

Philadelphia Pepper Pot SoupAccording to Tonya Hopkins, The Food Griot, Philadelphia Pepper Pot Soup, a favorite dish of George Washington, is quintessentially West African in style, including the addition of a whole hot pepper to flavor the soup. It was popularized as a street food in Philadelphia by Black women like the one pictured here. In the 20th century it was commercialized for a brief time by Campbell's, but its popularity waned by the late 20th century. Today, some chefs are reviving the food tradition. Further Listening:

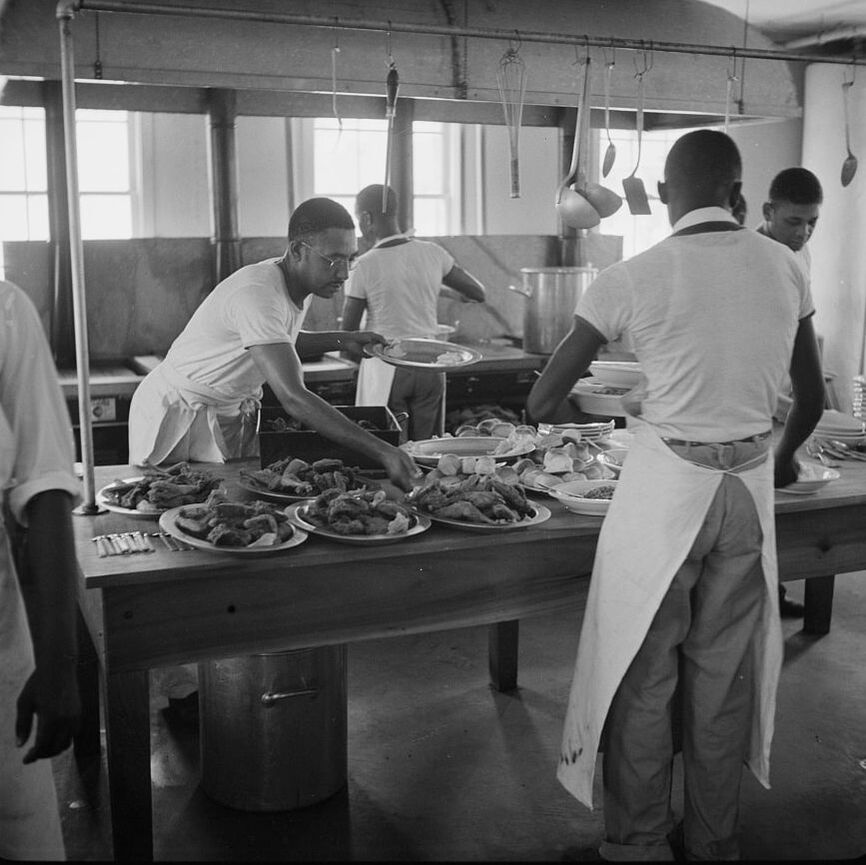

Fried ChickenAlthough who really brought fried chicken to the Americas is disputed (did it come from Africa, Scotland, or some confluence of the two?), by the late 18th century fried chicken is indisputably tied to the South and enslaved cooks. A special-occasion dish that, following the American Civil War, became a real source of income for freed people and their descendants, fried chicken became emblematic of soul food in the 20th century. Further Reading:

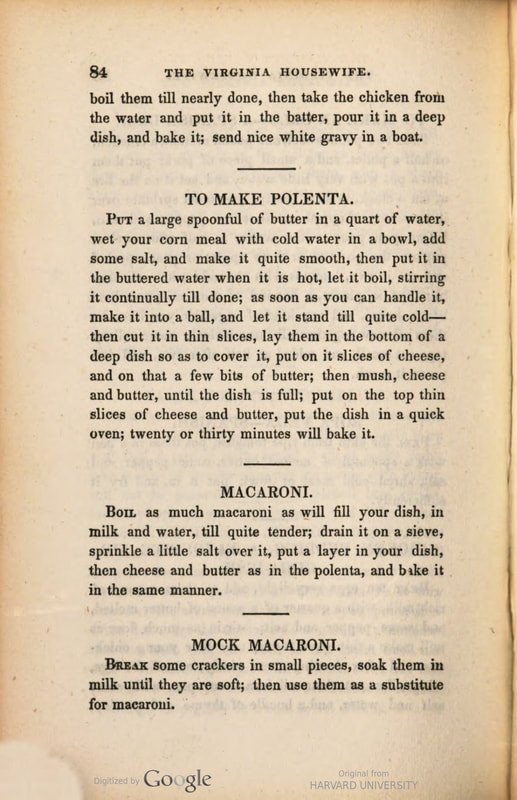

Macaroni and CheeseIs there a more quintessentially American food than macaroni and cheese? It has surprising origins, but was popularized early in American history thanks largely to an enslaved man - James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson's enslaved chef de cuisine. Its popularity among Black Americans is almost certainly due to the long history of macaroni and cheese in Southern (and mostly black-staffed) kitchens. Its use in railroad dining cars staffed by Black cooks also helps popularize it with Americans of all backgrounds. Further Reading:

Obviously, this is not a complete list, but I hope you learned a little something new with this post. As we all celebrate Juneteenth, let's not forget to keep recognizing the contributions of enslaved people and their descendants in contributing significantly to American food and culture throughout our nation's history. Want to learn more? Check out last year's "Black Food Historians You Should Know" for even more further reading. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

1 Comment

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

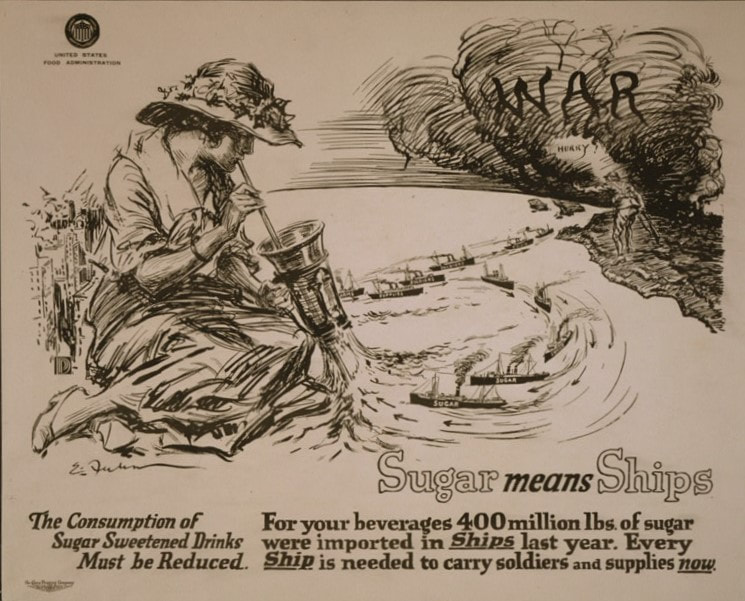

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. "Sugar means Ships. Consumption of Sugar Sweetened Drinks Must be Reduced. For your beverages 400 million lbs. of sugar were imported in Ships last year. Every Ship is needed to carry soldiers and supplies now."

This unobtrusive but nonetheless striking propaganda poster from the First World War was produced by artist Ernest Fuhr in 1917 for the United States Food Administration. In it, a soldier stands on the shores of Europe, rifle in hand, beckoning and shouting "Hurry!" to steamships carrying supplies from the United States as he heads toward the dark clouds of War. At left, in the foreground, a fashionable young woman drinks from a giant soda fountain cup. By sucking on the straw, she diverts more than half of the steamships, these labeled "sugar," back to the United States and into her cup. Although sugar was not rationed for civilians until the fall of 1918, a number of factors are at play here. First, is that unlike during World War II, the United States had poor mobilization of industry. In the short year and a half that the United States was in the war, not a single merchant ship was completed in time for war service, though 122 were started and completed after the war. In addition, even when the United States was a neutral country, German U Boats were always a risk (see: the sinking of the Lusitania). When it came time to ship millions of troops and supplies overseas, every ship possible was pressed into service. At this time, although the United States did produce its own sugar, largely through sugar cane plantations in Louisiana, it also purchased a great deal of sugar from the Caribbean, particularly Cuba. With railroads also tied up as goods and people moved east, ships were among the most efficient ways to ship shelf-stable staples like sugar. Leading up the U.S. entrance into the First World War, the United States had the highest per-capita sugar consumption in the world, consuming 85 pounds of sugar per person annually, compared to just 40 pounds in England. This extremely high sugar consumption was tied in part to the Temperance movement. Under the conventional wisdom of white, middle- and upper-class Protestants, alcohol was a social evil, and the basement saloons and bars that dotted urban neighborhoods throughout the country, with their free lunches to entice customers inside to drink more beer and other liquor, were dens of iniquity, tempting working class men to drink up their wages, to the detriment of their families. Nevermind that for many immigrant communities, social drinking was a convivial community event that often involved women and children (the Yankee reformers would be horrified). Soda fountains and tea rooms were a growing alternative. Soda fountains in particular were attractive to young people. And the reputation of fizzy "mineral" waters and "tonics" like Coca-Cola (which contained cola leaves - the main ingredient in cocaine) gave a veneer of health to what was otherwise sugar water. Ice cream was another extremely popular dessert turned snack in the Progressive Era and commercial production skyrocketed in the years leading up to the war. Tea rooms served fancy iced tea cakes and cookies, sweetened tea, and "dainties" like creamy fruit salads made with Jell-O - and plenty of sugar. The conventional nutrition wisdom of the time was that sugar was a carbohydrate, and carbohydrates gave you energy, therefore, sugar was good for you. Although sugar was not rationed for civilians during the war, it was for commercial enterprises. The production of ice cream and soda were both restricted during the war starting in the fall of 1917, and restaurants, hotels, and railroad dining cars were banned from leaving sugar bowls on the tables, as had previously been the norm. Civilians were encouraged to give up their sugar addictions, or at least transfer them to other sweeteners like honey, corn syrup, molasses, and maple syrup. Recipes for cakes, cookies, and preserving with these sugar alternatives were released to the public as part of the war effort. Although it's not clear if these efforts did have an effect on American sugar consumption during the war, the popularity of soda fountains, ice cream, gelatin fruit salads, and candies continued to be an American obsession. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed