|

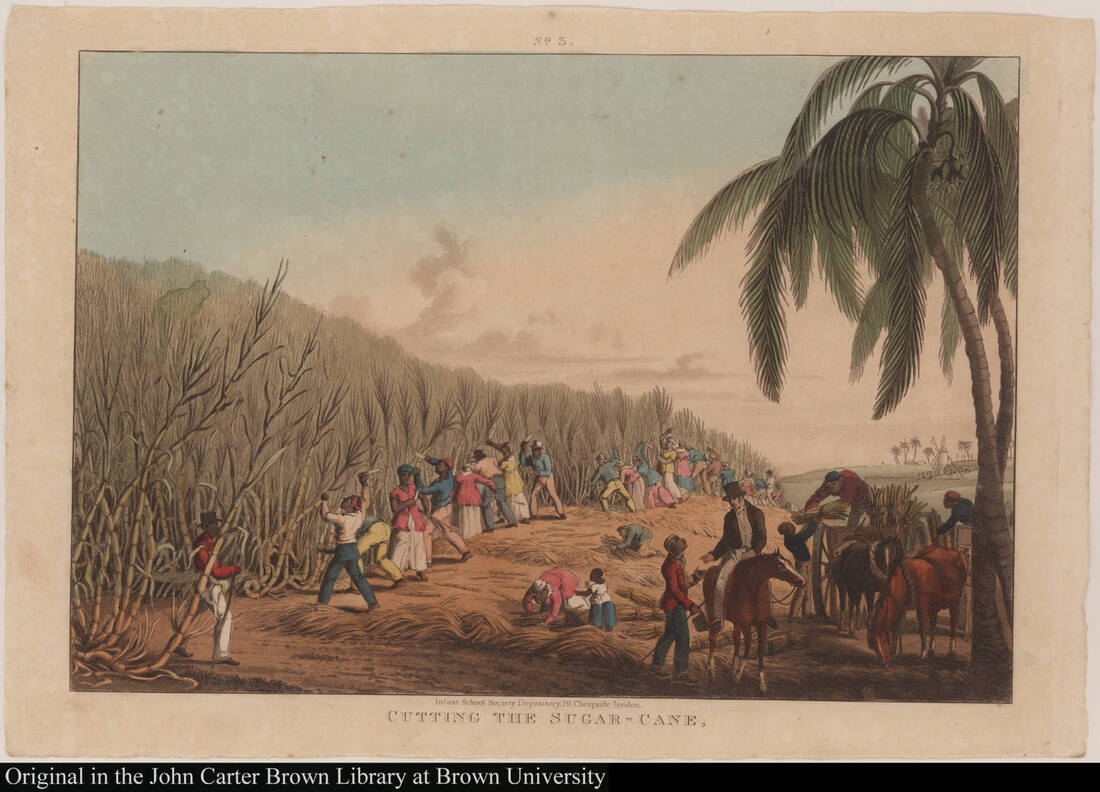

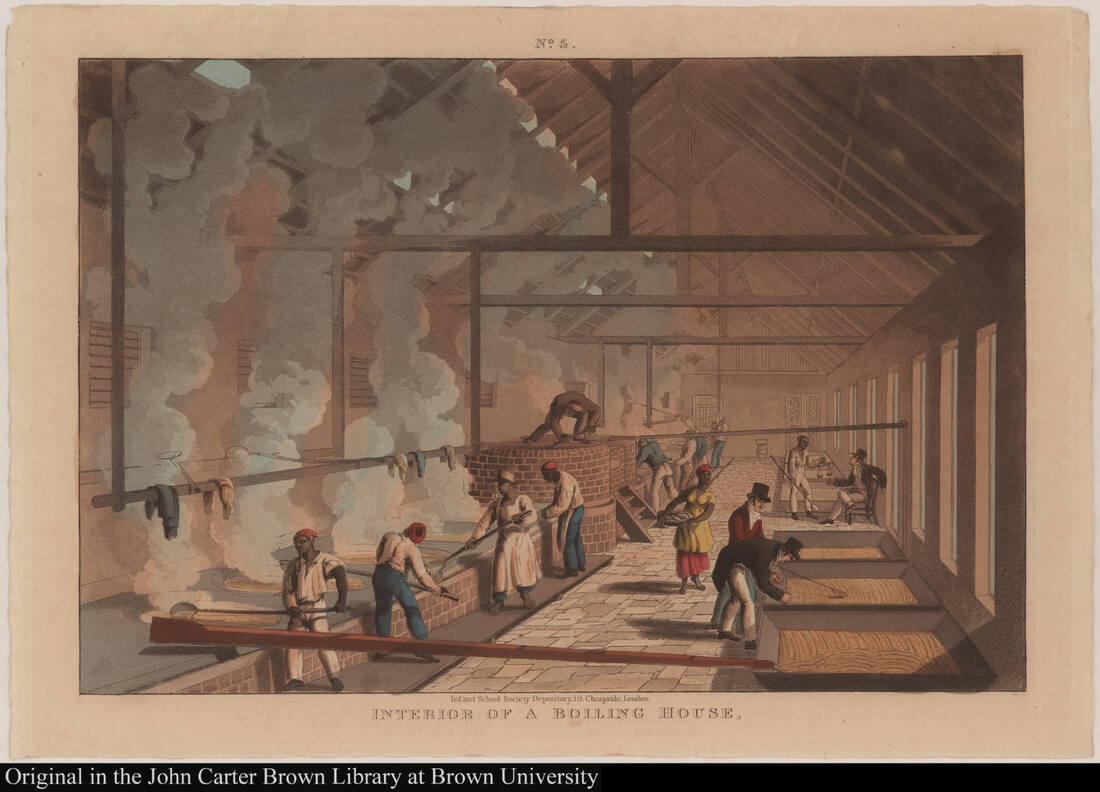

The United States owes enslaved people and their descendants a lot. White Americans don't like to admit that often, but we really do. And to me, nowhere is that more evident than in our modern food system. Today is Juneteenth - a celebration of the end of slavery in the United States. Not on the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, which was issued on January 1, 1863 and which LEGALLY freed all enslaved people in the country. No, it took until June 19, 1865 - fully two and a half years later, for the message (and the enforcement) to finally arrive in Texas with a group of Union soldiers. For although all enslaved people in the United States were deemed free in 1863, the Confederacy did not recognize that authority, and continued to enslave and exploit Black people until forced to do otherwise by armed Federal troops. So to celebrate Juneteenth, you can certainly look up recipes and plan a party. But I think it's equally important to recognize incredible contributions enslaved people made to our food system, and for Americans of all backgrounds to reckon with the truth that much of our modern foods are the direct result of violence and exploitation. At last night's Food History Happy Hour, viewer Cathy brought up that we learn a lot in school about the contributions of White immigrants, but not so much about the contributions of enslaved people. And that struck me as both very true and very sad. Because so much of what is considered American food is intimately connected to both West Africa and the enslaved people brought here against their wills. People who experienced incredible hardship still had the perseverance and fortitude not only to hold on to their foodways on the horrific voyage across the Atlantic, but to persist in keeping those foodways in the United States. Not all of the foods listed below came from West Africa, but all are a direct result of the enslavement of West Africans. Editor's note: The Food Historian is an Amazon affiliate. Any purchases you make through the book links below will help support blog posts like this! SugarWe can start with the biggest one. Before the enslavement of Africans in the Caribbean and American South, sugar was produced in India at great expense. By kidnapping people and forcing them into bondage, enormous sugar plantations were established by Europeans throughout the Caribbean, and later in American states like Louisiana. Sugar plantations were some of the most brutal of the plantation economy. The life expectancy of an enslaved person was very low, and some islands imported double or triple their populations per year in slaves, as many died faster than they could be replaced. Today, sugar is almost completely mechanized, but most of our modern foodways - sugary desserts in particular - are possible only through the massive effort to enslave millions of people for profit. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sugar became increasingly affordable, as sugar production mechanized. The cultivation of sugarcane remained incredibly labor-intensive. Sugarcane harvesting, for example, was not really mechanized in the American South until World War II. As an aside, I recently learned that the United States was active in the slave trade for decades after it was made illegal, and that the primary point of destination for American slave traders after kidnapping mostly children from West Africa was the sugar plantations of Cuba. This illegal trade continued until the 1860s. Further Reading:

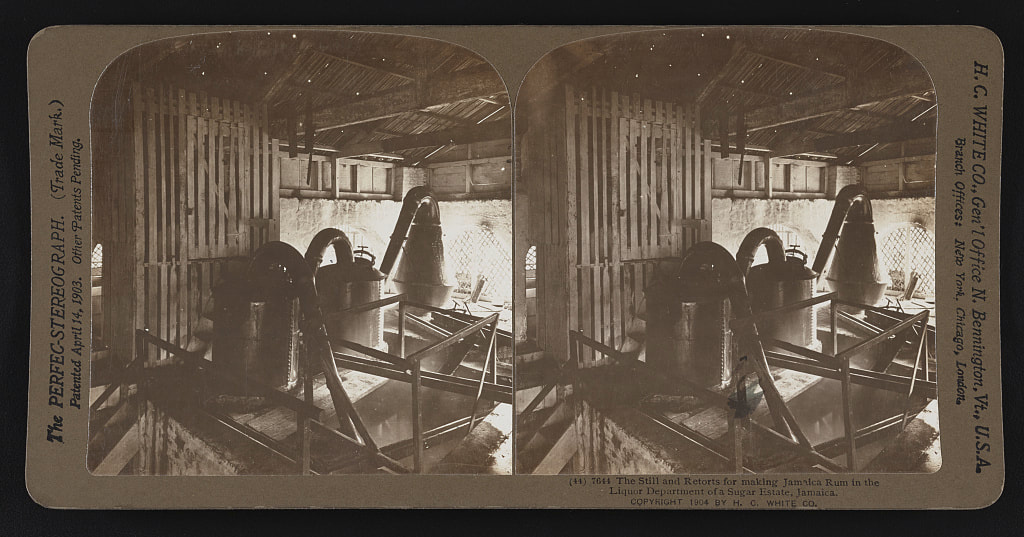

MolassesMolasses may make you think of baked beans, or gingerbread, or soft molasses cookies. But molasses is a byproduct of the sugar industry, and therefore slavery. Molasses, the cheapest sweetener, also was used in slave rations and was a major foodstuff among poor Whites throughout the United States until the mid-20th century. But although Molasses becomes intimately connected with New England and pioneer foodways, it has another important use... RumRum may make you think of pirates, but it was actually developed as a way to transform relatively worthless molasses into a high-value commodity. And while vicious pirates guzzled it by the gallon, it was also a huge economic engine not only in the Caribbean, but also in New England, where it was produced and used to purchase people and goods in West Africa as part of the slave trade. The irony being that a product largely produced by slaves (first in producing the molasses, and then often again in producing rum) was being used to purchase more slaves should not be lost on anyone. Further Reading:

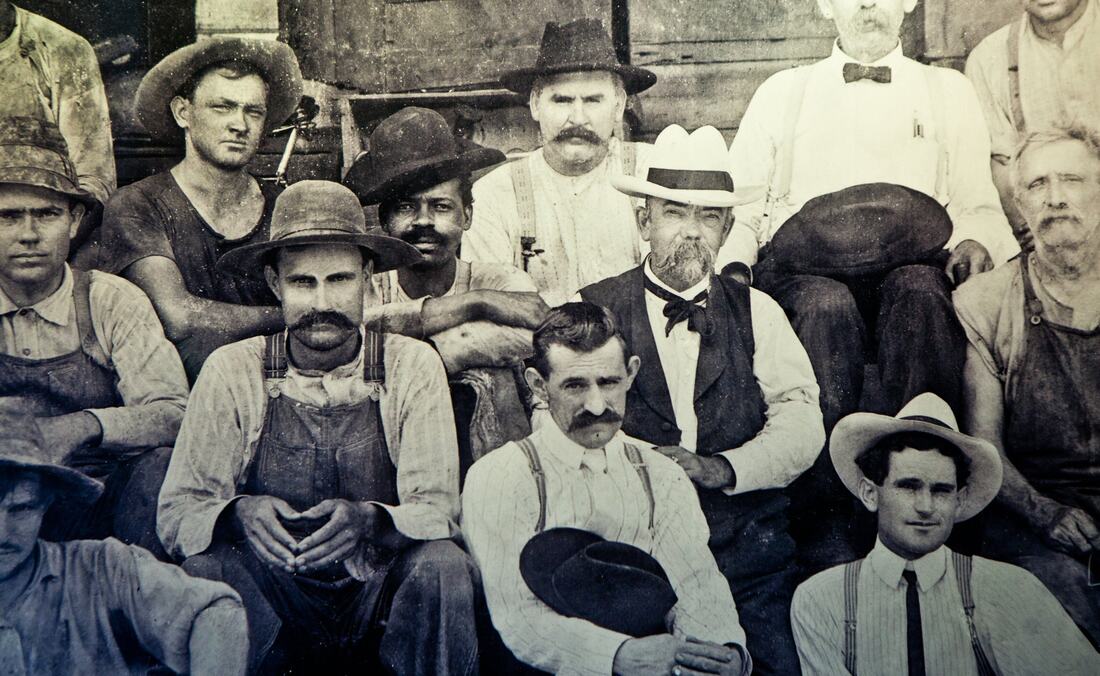

Jack Daniels WhiskyWhile we're on the topic of alcohol and slavery, let's just take a moment to recognize that Jack Daniels was taught how to make whisky by Nathan "Nearest" Green, an enslaved man who used a charcoal filtering technique he learned to clean water in West Africa to filter the distilled alcohol. He was Jack Daniel's first master distiller, but only got credit more recently. Read the full story. RiceI know what you're thinking - Sarah, how are you going to relate RICE to slavery? Well, although today we consume a lot of rice developed in India and Japan, throughout the 19th century, Carolina Gold rice was king. Rice production in South Carolina dates back to the 18th century and plantation owners specifically sought out and captured West Africans skilled in rice agriculture and enslaved them to operate their rice plantations. The White plantation owners got obscenely rich on this scheme. Although Carolina Gold rice is no longer as prevalent in American food culture, it still made a huge impact on the economy of the South. Further Reading:

OkraNative to Ethiopia and cultivated in Africa as early as 12,000 years ago, okra was brought to North America by enslaved West Africans, the seeds braided in their hair. It went on to spread throughout the American South, influencing such dishes as regional varieties of gumbo and often served stewed with tomatoes or breaded and fried. Although not as widespread as some of the other foods on this list, okra still maintains a huge impact on American foodways. Further Reading:

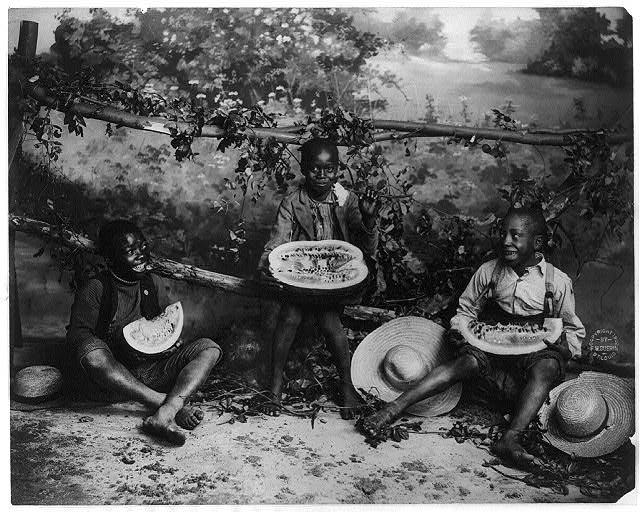

WatermelonDeveloped in the Kalahari desert of Africa, the watermelon was carefully bred by Indigenous Africans to go from a thick-rinded, rather tasteless melon to the sweet, juicy treat we know today. Although it did spread to Egypt and the Middle East, it was likely introduced to North America via the slave trade - either purchased by slave traders and kidnappers, or brought over by enslaved people themselves. The American stereotype of associating Black folks with watermelon as an insult is still around today. Further Reading:

Black Eyed PeasNative to West Africa, black eyed peas, sometimes called cowpeas, were brought to the Americas by enslaved Africans. In the U.S. they are most commonly known as the main ingredient in "Hoppin' John," a popular dish consumed on New Year's Day for good luck. Two stories about black eyed peas and luck have emerged over the years. The first is that when General Sherman made his way through Georgia, one of the only foods the Union Army did not take was black eyed peas, as they were considered cattle fodder in the North. The Confederate Army subsisted on this "slave food," an irony they clearly did not understand. The other story, and one I think far more likely, is that black eyed peas were one of the celebratory dishes consumed on January 1, 1863 - the day the Emancipation Proclamation became law. Further Reading:

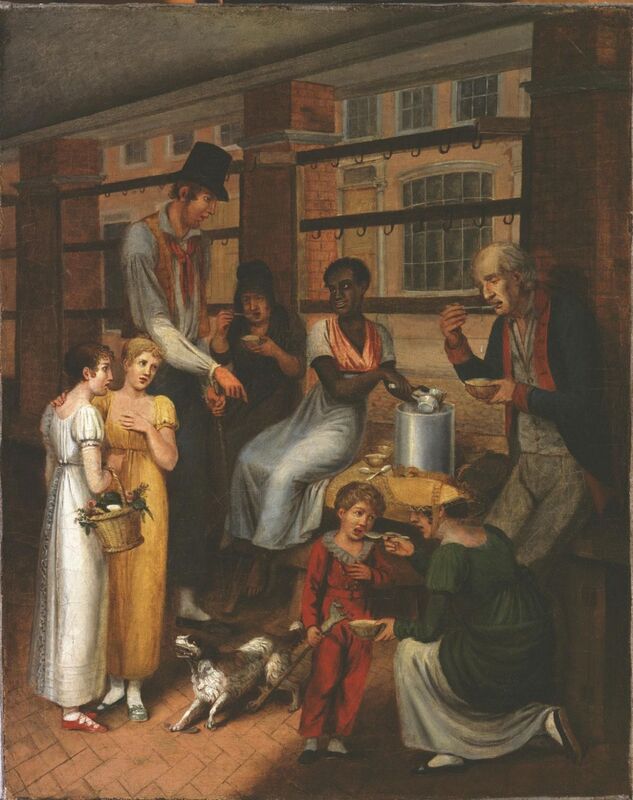

Philadelphia Pepper Pot SoupAccording to Tonya Hopkins, The Food Griot, Philadelphia Pepper Pot Soup, a favorite dish of George Washington, is quintessentially West African in style, including the addition of a whole hot pepper to flavor the soup. It was popularized as a street food in Philadelphia by Black women like the one pictured here. In the 20th century it was commercialized for a brief time by Campbell's, but its popularity waned by the late 20th century. Today, some chefs are reviving the food tradition. Further Listening:

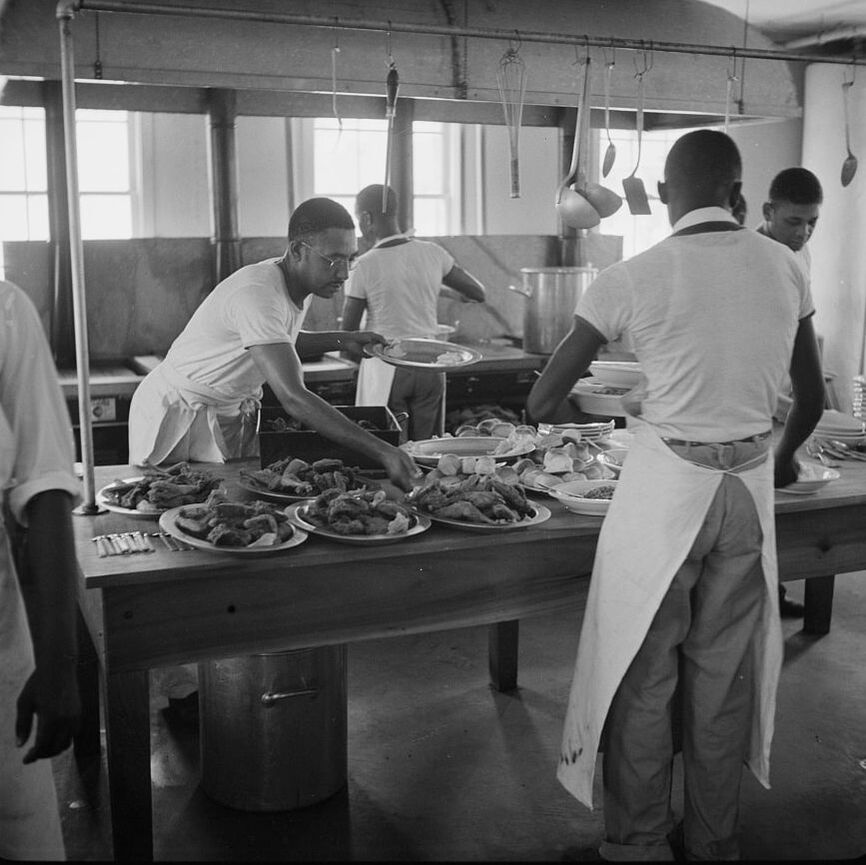

Fried ChickenAlthough who really brought fried chicken to the Americas is disputed (did it come from Africa, Scotland, or some confluence of the two?), by the late 18th century fried chicken is indisputably tied to the South and enslaved cooks. A special-occasion dish that, following the American Civil War, became a real source of income for freed people and their descendants, fried chicken became emblematic of soul food in the 20th century. Further Reading:

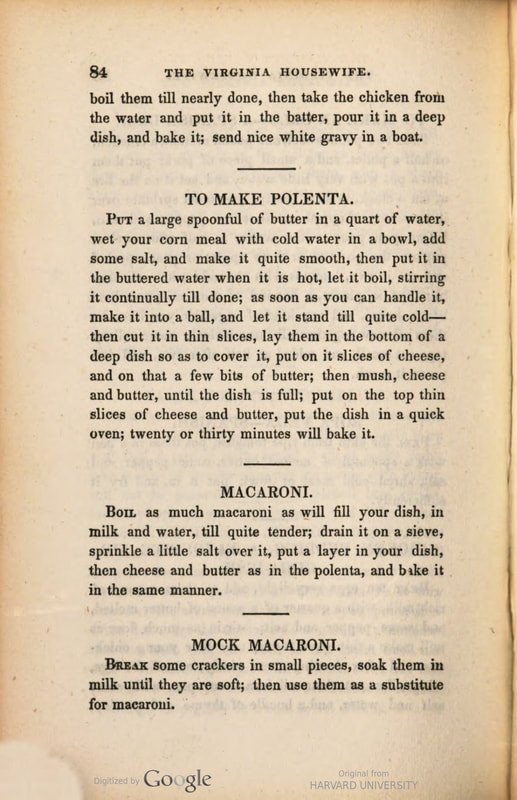

Macaroni and CheeseIs there a more quintessentially American food than macaroni and cheese? It has surprising origins, but was popularized early in American history thanks largely to an enslaved man - James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson's enslaved chef de cuisine. Its popularity among Black Americans is almost certainly due to the long history of macaroni and cheese in Southern (and mostly black-staffed) kitchens. Its use in railroad dining cars staffed by Black cooks also helps popularize it with Americans of all backgrounds. Further Reading:

Obviously, this is not a complete list, but I hope you learned a little something new with this post. As we all celebrate Juneteenth, let's not forget to keep recognizing the contributions of enslaved people and their descendants in contributing significantly to American food and culture throughout our nation's history. Want to learn more? Check out last year's "Black Food Historians You Should Know" for even more further reading. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

1 Comment

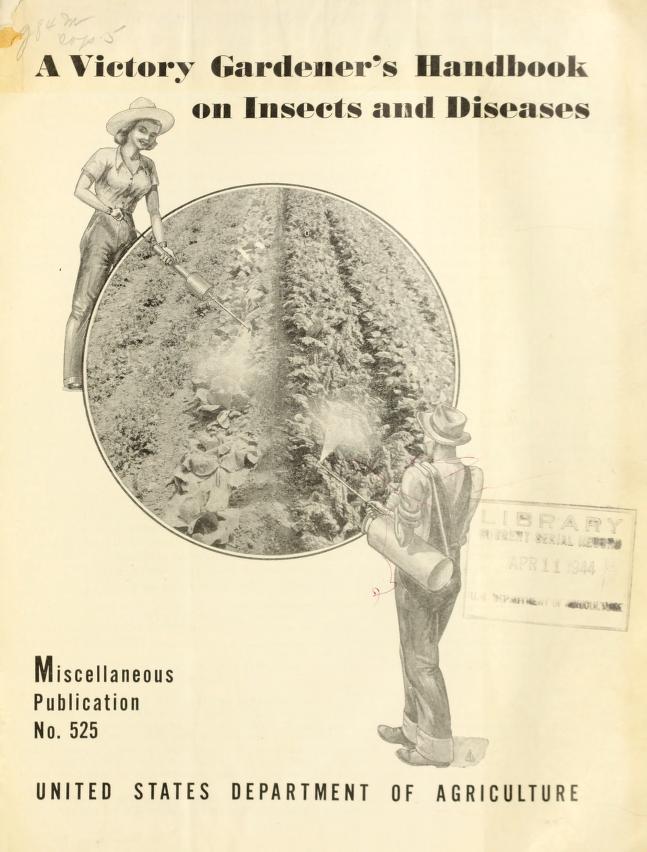

When it comes to modern ideas about Victory Gardens, there's a lot of romanticism and rose-colored glasses. Hearkening back to a kinder, gentler time when everyone pulled together toward a common goal and had delicious, organic vegetables in their backyards while they did it. But the reality was often much different from our modern perceptions. This propaganda poster is a good example of that. "Shoot to kill!" it says - "Protect Your Victory Garden!" In it, a woman wearing blue coveralls and a wide-brimmed hat, a trowel in her back pocket, sprays pesticide on a large, green insect (a grasshopper?) taking a bite out of an enormous and perfectly red tomato. She is protecting her victory garden from the "fifth column" of insect predation. "The Fifth Column" was a term used in the United States to describe sabotage and rumor-mongering by foreign spies. In this instance, insects become the "fifth column" because the act of eating crops threatens wartime food supplies, and is therefore sabotage by a foreign enemy. The food supply had to be protected and maximized at all costs. Anxieties around food supplies, especially in the winter when commercially produced foods might be scarce, meant that victory gardens took on special urgency. For the first time in at least a generation, Americans were having to put up their own food to help them get through the winter. And making every quart count was only possible if the garden did well. Lots of militarized language was used in propaganda concerning food, but none as war-like as the battle against pests in the victory garden. The idea that gardening before the 1950s was all organic is a common misconception. Even prior to the First World War, farmers and even some gardeners were dusting their crops with Paris Green and London Purple. Paris Green was a bright green toxic crystalline salt made of copper and arsenic. London Purple was calcium arsenate - normally white, but also a byproduct of the aniline dye industry, and was therefore sometimes tinged purple. Along with arsenate of lead, another salt, these three were termed arsenical pesticides and were used often in agriculture. The arsenic in rice scare from a few years ago was likely due to elevated levels of arsenical pesticide residue in the soil. Especially since rice from California, which first began to be commercial produced in 1912, but was not widely available across the country until the 1960s. That late adoption of rice agriculture meant that production was not as exposed to arsenical pesticides as elsewhere in the U.S. In 1944, the USDA published "A Victory Gardener's Handbook of Insects and Diseases" that identified common pests and suggested remedies. Calcium arsenate and Paris green were recommended (albeit with warnings about arsenic residue), along with:

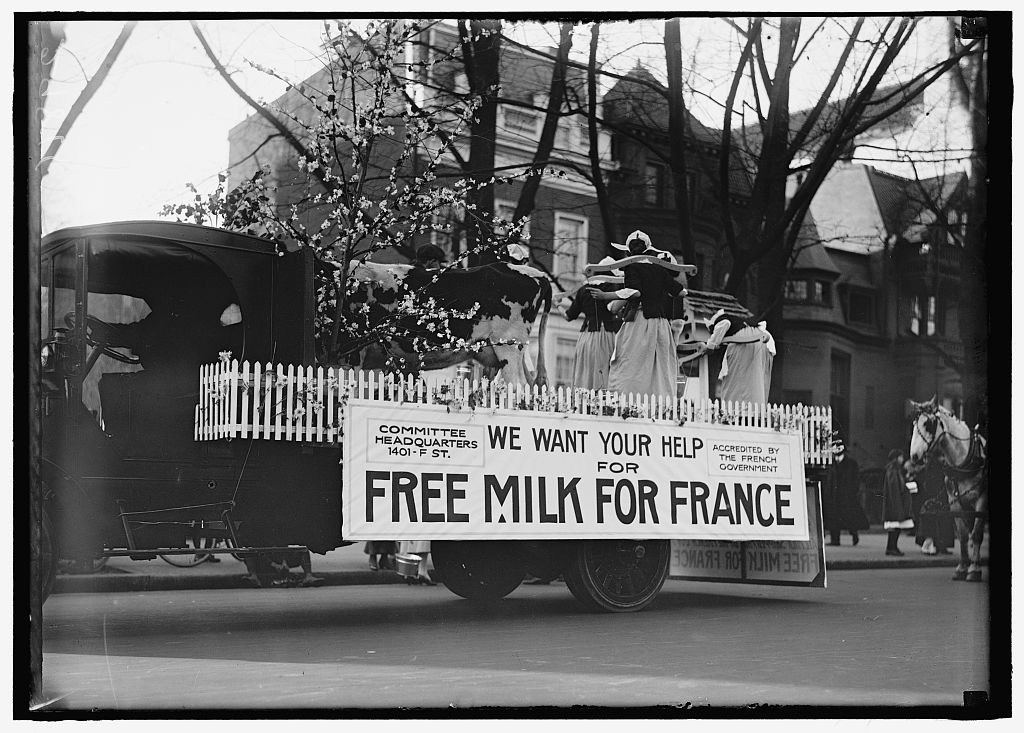

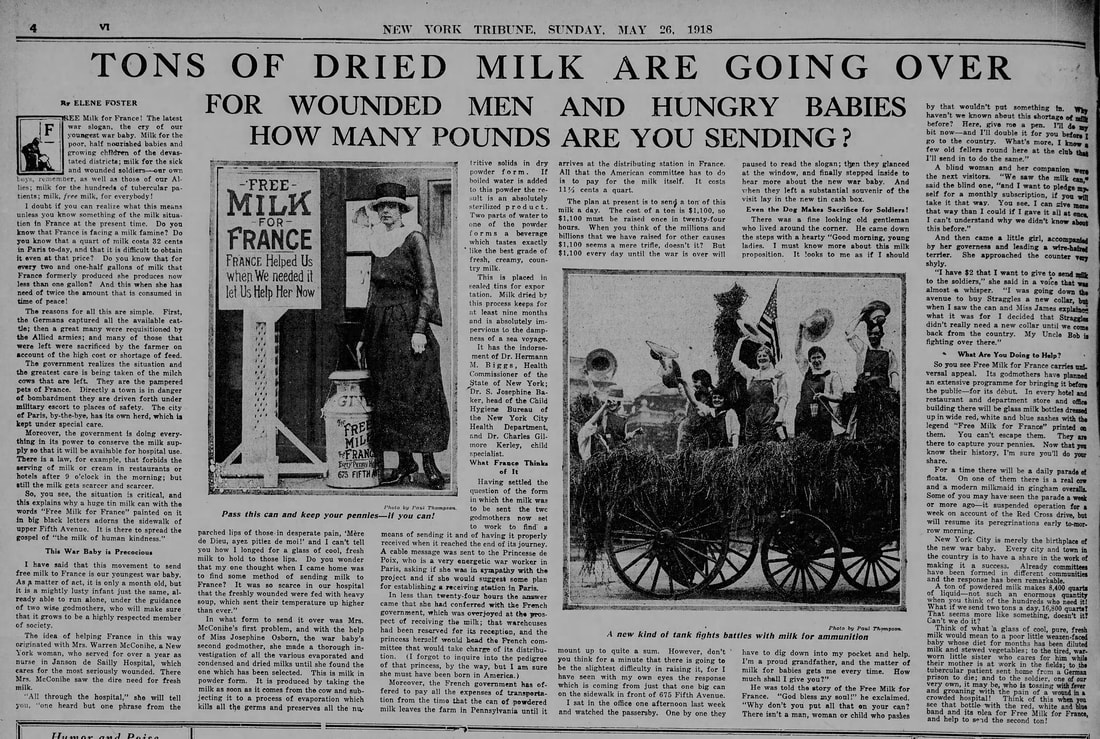

Although some people may have chosen not to purchase pesticides, likely due to expense more than concerns about poisoning, the emphasis on the danger pests posed to the general food supply continued. Hand atomizers, which is what the hand sprayer in the propaganda poster is called, were frequently depicted in print and even on film. Despite USDA warnings about application safety, no one is ever seen applying the highly toxic, aerosolized liquid pesticides with protective equipment. However, the science of the effects of exposure to toxic chemicals was not yet well-studied. DDT, invented in 1939, was deemed a miracle chemical and helped dramatically reduce diseases like malaria and water-borne bacteria that in previous wars had sometimes killed more soldiers than the conflict itself. Because soldiers faced no immediate effects, the chemical was deemed safe, and used everywhere from farms to a treatment for lice in children. But like the arsenical pesticides, the effect was cumulative, and it wasn't until Rachel Carson's 1962 Silent Spring that Americans began to wake up to the dangers of pesticides. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! Last week we learned about the big Dairy Exposition during WWI - this week we're examining the Free Milk for France movement, which coalesced about the same time. This propaganda poster by F. Louis Mora from 1918 is one of the more famous of the food-themed propaganda posters of the First World War. In it, a soldier ladles milk out of a large milk can into the bowl of a French child, one of several, accompanied by a wounded French soldier with a tin cup and crutch. Judging by how bundled up everyone is, it's probably winter. Ironically, the Free Milk for France campaign actually focused on provided dried milk. On May 13, 1918, the Committee to Obtain Free Milk for France launched a fundraising parade. "The parade, consisting of two floats and an escort of soldiers and sailors, including a navy band, started from the First Field Hospital Armory at Sixty-sixth Street and Broadway and canvassed the city as far down as the Wall Street District," reported the New York Times the following day. "The money will be used to purchase powdered milk to be sent to France for the use of wounded soldiers, babies, and tubercular patients." In the above photo, a woman dressed in overalls and a straw hat drives a team of horses pulling a large hay wagon. Another woman riding on the wagon is dressed in a military-style outfit holding a small bucket and a wooden shoe - likely soliciting donations. An American flag attached to a sheaf of hay is behind them. The first parade made over $1,000. The group launched another parade a few days later, on May 17th, parading "down Fifth Avenue from Fifty-ninth Street to Twenty-second Street yesterday afternoon." Featuring seven floats, including young society girls "dressed as milkmaids."  Free Milk for France parade, motor truck with a float of milkmaids with a live cow and flowering tree, surrounded by a white picket fence. A large sign reads, "We want your help for Free Milk for France," with smaller notes - "Committee Headquarters 1401-F St." and "Accredited by the French government." Harris & Ewing photographers, May, 1918. Library of Congress. In the above black and white photo, a flat bed truck features a large float carrying a flowering tree, a live dairy cow, and at least five young women dressed as Brittany milkmaids. The edges of the float are surrounded by a white picket fence. On May 19, 1918, the New York Times published "America Sending Milk to France." The article is transcribed below: One of the greatest sources of suffering in France has been lack of milk. The causes for this lack are manifold. In many instances the Germans slaughtered cows for beef whose greater value lay in their milk; in other instances the Government of France requisitioned the animals for army use, and in still others the farmers found themselves forced to kill their cattle on account of the shortage of pasture and fodder. All in all there have been lose to the people of France about 2,000,000 cows, and the main source of maintenance of infants and children, of the crippled and the wounded, the sick and tubercular, lies in milk. At present the death rate of children in France is from 58 to 98 per cent. The number of wounded and crippled needs no repetition here. The increase in the ranks of the tubercular is appalling. Outside Belgium, perhaps, there is no other country which has so greatly succumbed to this disease. The supply of milk in France has been depleted at least 16 per cent. Under present conditions infants must take vegetable stews as a food substitute. What this means to their health and their growth the mortality figures show. Wounded soldiers get heavy soups, which are well-nigh fatal in their effects. The tubercular of France have almost been forgotten. Milk has become a luxury far beyond the reach of the majority of them. In order to do something to meet this situation and to conserve the milk they have, the French Government is taking vigorous measures. Great care is devoted to the protection of milch cows. From bombarded towns, under military escort, two or three at a time are led back to places of safety. Farmers are urged to make all sacrifices possible to provide proper feed for them. Within Paris a herd of cows is kept under civic care. Government restriction now forbids the serving of milk or cream for any purpose in restaurants, hotels, or public eating places after 9 o'clock in the morning. In private homes, rich or poor, milk is only given to young children and the sick. Milk in Paris costs 32 cents a quart, when it can be bought. It was in a desire to do something to change these conditions that Mrs. Warren McConihe and Miss Josephine Osborne organized the Free Milk for France Fund. Mrs. McConihe had seen the soldiers suffering greatly for want of milk, she had seen them grow feverish under the influence of heavier foods. She had seen the Belgian and French refugees almost starved for lack of milk. Upon her return to this country she found that America had enough milk to send some across. Because it requires less shipping space, she chose powdered milk. It is scientifically prepared by subjecting fresh, pure, full-creamed milk to a rapid evaporating process, which preserves the nutritive solids and keeps without ice for months. The milk when prepared costs about 13 cents a quart. There is no other cost. The Government of France has taken over the details of transportation. It is the aim of the organization to send one ton of milk a day. All that is necessary is to mix with hot water. The milk in this form has been recommended even for home use by Dr. Hermann M. Biggs, State Health Commissioner; Dr. S. Josephine Baker of the Child Hygiene Bureau, and Dr. Charles G. Kerley, a child specialist. At a cost of $1,100 a ton of dried milk is sent across, enough to feed 8,400 babies or wounded soldiers or tubercular patients. $52 will send 100 pounds of dry milk or 40 quarts of liquid; $5.20 will sent ten pounds, or forty quarts, and 13 cents will send one quart. The aim of the Free Milk for France organization is to have the nation as a whole respond to its work. Branches are being organized all over the country. The headquarters of the fund is at 675 Fifth Avenue. These two parades, held during the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition, were just the first of a campaign that would last into 1919 and spread across the country. By the end of 1919, there were campaigns in thirty-six states, and the distribution in France was being organized by Madame Foch - wife of French General Ferdinand Foch. The rhetoric around milk and its importance in the diet, especially for children and the sick, would be replicated in the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! For the first time in my life I've signed up for a CSA and last week got my first box. It was just crammed with greens! A bunch of lactinato kale, a bunch of rainbow chard, a bag of spinach, two stalks of green garlic, two little red lettuce heads, a bunch of fresh basil, a purple daikon radish, and a dozen eggs! Thankfully we love greens in my household and simple creamed greens is one of my favorite ways to eat them. You may be familiar with creamed spinach, but in the 18th and early 19th centuries, spinach and cream was more likely to be served with sugar than with garlic. It's really not until the turn of the 20th century that savory creamed spinach becomes a steakhouse staple (and even then it's often still got nutmeg in it). Although creamed spinach is quite good, I actually prefer to cream sturdier greens. Kale, in particular, especially the curly kind, is very good creamed. It's not as meltingly soft, but I prefer a little more texture. Many creamed greens recipes use a white sauce or cream cheese, and while those are good, the easiest way to make them is simply to reduce cream with a little salt. It gives the greens a creamy coating without overpowering them. Creamed Spring Greens on ToastThis dish turned out even more delightfully than I expected. Be forewarned - like most dishes of cooked greens, it takes a lot to make a lot. This recipe results in really just two hearty servings - four if you're eating other foods on the side. You can of course substitute just about any hearty greens in this dish. For a richer dish, use heavy cream instead of half and half (which was all I had in the fridge). 2 tablespoons butter 2 stalks green garlic 1 bunch lacinato kale 1 bunch rainbow chard 1/3 cup or so half and half 4-6 small leaves fresh basil 2 inch square of feta, plus extra for garnish salt to taste whole grain toast In a dutch oven, melt the butter over medium-low heat. Slice the green garlic thinly crosswise, white and green stalk (discard the tough leaves), then mince. Add to the butter. Chiffonade the kale and finely slice the stems of the rainbow chard. Add to the butter and garlic and increase the heat to medium. Sautee until the stalks are tender. Chiffonade the swiss chard leaves and add to the pot. Sautee a little longer, until all greens are wilted. Meanwhile, mince the basil finely. Add the cream, basil, and feta. Increase the heat to medium-high and simmer until the cream thickens and is almost completely absorbed. Pile on hot toast and garnish with more feta. The garlic and basil flavors were subtle but delicious. If you like stronger flavors, add more basil and use clove garlic, or add the green garlic later in the cooking process. You might think that a pile of greens with a few crumbs of cheese is not a very satisfying meal, but you would be wrong. The greens are part silky, with tender but toothsome bits of stalk. The feta adds a salty tang and it's all tinged with fragrant basil and garlic. It is very true, however, that two whole bunches of greens does cook down quite a lot, and my husband and I ate the whole pot, just the two of us. So if you're looking to get more greens in your diet, this is a great way to go! But if you're cooking for a crowd, definitely double or triple the recipe. Do you have a favorite way to eat dark leafy greens? The Food Historian blog is supported by tips, members, and patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 on Patreon or with a membership below and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase any of the listed books, you'll help support The Food Historian!

A friend of mine is a retired librarian from New York University. A few weeks ago he told me a fascinating story - in the 1970s, in order to make room in the library for new works, the powers that be at NYU decided to get rid of all the master's theses in the library collection. Master's graduates who were still alive and with addresses on file were contacted and asked if they would like their originals. Some departments saved works they thought were important. But most were destined for the dumpster.

A young librarian had been hired specifically to dispose of the collection. One day, someone walked in off the street, pulled a typed thesis off the shelf, handed it to the that librarian, and said, "This is an extremely important work, please don't throw it out," and walked away. That librarian kept that thesis, and when she quit at the end of the depressing project, she passed it onto my friend, who tucked it way in his desk drawer. Almost a decade later, in the 1980s, he happened to be walking by the circulation desk when a "rookie librarian" was dealing with a request to see a Master's thesis for the first time. "Isn't that right? All the MA theses were thrown away?" she asked him. My librarian friend started to say, "Yes that's right," and the he looked at the index card the researcher had handed over, and added, "except for the one you are looking for, which is in my desk." Rumors of this particular thesis had been swirling among scholars for years, which was how the researcher knew exactly what to request, despite the fact that it was not listed in the library catalog. That work was "The Chinese Restaurants in New York" by master's student Louis H. Chu, which he completed in 1939, along with his Master's degree in Sociology. It WAS an extremely important work - it cataloged Chinese restaurants in New York City at a time when people didn't seem to care much about food history, or about Chinese America. Chu's thesis was largely forgotten. He is better known for going on to write the groundbreaking novel, Eat a Bowl of Tea (1961), which was set among the lives of unmarried Chinese immigrant men in New York City's Chinatown. Although it was not a critical success at the time, it found greater acclaim in the 1970s. In 1989 it was made into a film. It is still cited as one of the most influential works of Asian-American literature.

In addition to his book, Chu also hosted a long-running radio program of Chinese music, and in 1961, he appeared as the mystery guest on the popular television show, "What's My Line?" as part of a promotion for Eat a Bowl of Tea.

"The Chinese Restaurants of New York," however long it languished in that fateful desk drawer, did go on to influence of a generation of researchers of the Chinese-American experience. The thesis is cited in at least twelve subsequent works, including influential recent books like Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America by Yong Chen (2016), Eating Asian American: A Food Studies Reader (2013), and Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family Restaurants by John Jung (2010).

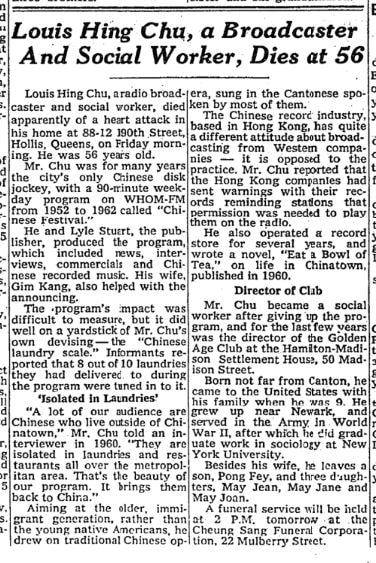

Louis Hing Chu died at home in Hollis, Queens of an apparent heart attack on Friday, February 27, 1970. He was just 56 years old. His obituary focuses on his work as a disc jockey for WHOM-FM, where he played Chinese music for a 90 minute show called "Chinese Festival," which aired on weekdays between 1952 and 1962. Here's the full text of the obituary, "Louis Hing Chu, a Broadcaster and Social Worker, Dies at Age 56," published in the New York Times on March 2, 1970:

Louis Hing Chu, a radio broad caster and social worker, died apparently of a heart attack in his home at 88‐12 190th Street, Hollis, Queens, on Friday morning. He was 56 years old. Mr. Chu was for many years the city's only Chinese disk jockey, with a 90‐minute week day program on WHOM‐FM from 1952 to 1962 called “Chinese Festival.” He and Lyle Stuart, the publisher, produced the program, which included news, inter views, commercials and Chinese recorded music. His wife, Gim Kang, also helped with the announcing. The program's impact was difficult to measure, but it did well on a yardstick of Mr. Chu's own devising— the “Chinese laundry scale.” Informants reported that 8 out of 10 laundries they had delivered to during the program were tuned in to it. ‘Isolated in Laundries’ “A lot of our audience are Chinese who live outside of Chinatown,” Mr. Chu told an interviewer in 1960. “They are isolated in laundries and restaurants all over the metropolitan area. That's the beauty of our program. It brings them back to China.” Aiming at the older, immigrant generation, rather than the young native Americans, he drew on traditional Chinese opera, sung in the Cantonese spoken by most of them. The Chinese record industry, based in Hong Kong, has quite a different attitude about broad casting from Western companies — it is opposed to the practice. Mr. Chu reported that the Hong Kong companies had sent warnings with their records reminding stations that permission was needed to play them on the radio. He also operated a record store for several years, and wrote a novel, “Eat a Bowl of Tea,” on life in Chinatown, published in 1960. Director of Club Mr. Chu became a social worker after giving up the pro gram, and for the last few years was the director of the Golden Age Club at the Hamilton‐Madison Settlement House, 50 Madison Street. Born not far from Canton, he came to the United States with his family when he was 9. He grew up near Newark, and served in the; Army, in World War II, after which he did graduate work in sociology at New York University. Besides his wife, he leaves son, Pong Fey, and three daughters, May Jean, May Jane and May Joan. A funeral service will be held at 2 P.M. tomorrow at the Cheung Sang Funeral Corporation, 22 Mulberry Street. Sadly, Chu died before his novel became more widely respected. And neither NYU nor UCLA, which holds the only other copy of his thesis, have ever seen fit to digitize "The Chinese Restaurants of New York," which seems a shame, given how influential it has gone on to become. I, for one, am just grateful to that unidentified person who knew the work well enough to try to save it, and for the librarians who did. My librarian friend updated me that he tried to request the original thesis, which is now cataloged, but was told it was "processing," which hopefully means it is being digitized, so it won't ever be at risk of destruction again.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

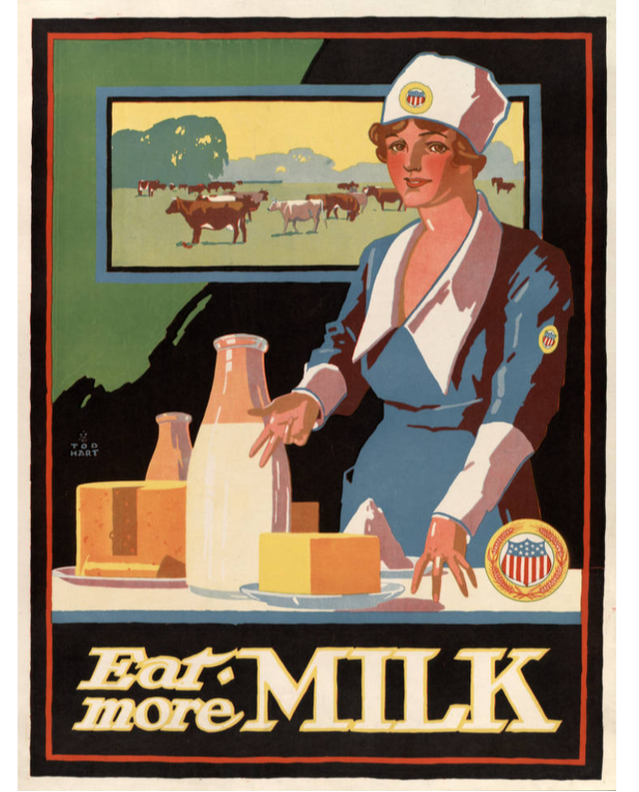

This beautiful propaganda poster from the First World War is the result of a controversy. The fresh-faced young white woman in her United States Food Administration-approved food conservation uniform and cap, gestures to a table with an enormous glass bottle of milk, a huge block of butter, a wheel of cheese, and what is either a mound of cottage cheese or some sort of milk pudding. A framed view of dairy cows in a green field floats behind her. It exhorts the reader to "Eat more MILK." But why? Throughout World War I in the United States, dairy farmers struggled. Feed prices went up, and retail prices of milk went up, but the wholesale prices that farmers got from milk dealers and dairies remained static. Despite dozens of local and state and federal inquiries, no single culprit for high milk prices was ever discovered. The result of high prices combined with government advocating for increased production and Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet, particularly for children, meant that by the spring of 1918 there was a serious milk surplus. For several years, the butter, cheese, and condensed milk industries had absorbed the milk surplus, but by the spring of 1918 they were also over capacity. The United States Food Administration, in conjunction with state governments, embarked on a campaign to try to get Americans to consume more milk, with limited success. In May of 1918, New York City hosted the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition at the Grand Central Palace. New York State Governor Charles Whitman opened the exposition, and United States Food Administrator Herbert Hoover also attended. Home economists praised milk-based dishes such as puddings, custards, and the use of cottage cheese and brick cheeses - hence the phrase "Eat more milk," rather than "drink," as drinking cows milk was not common among adults. Cottage cheese and brick cheese were touted as affordable meat alternatives. Despite the classic Progressive Era boosterism, including the attendance of "famous" cows at the exposition, retail milk prices remained relatively high, with seasonal dips in the spring and early summer. Federally fixed milk prices helped solve the problem short-term, but even after the war, dairy farmers were subject to a Congressional investigation to determine whether they price gouged consumers (they didn't), and the right of farmers to form co-ops was in danger of becoming illegal under anti-trust laws. Ultimately, it was falling grain prices and rising postwar demand that evened out prices, although to this day the dairy industry still struggles. Even after the war, Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet persisted, and were recycled during the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed