|

Note: This article includes descriptions of wartime violence, genocide, and violence against women. Sensitive readers be warned.

Earlier this year, on Armenian Remembrance Day, President Biden officially declared the actions of Ottoman Turkey against Armenians during the First World War to be genocide. While some people might be aware of the Armenian genocide, I think fewer Americans are aware that it was part of the First World War.

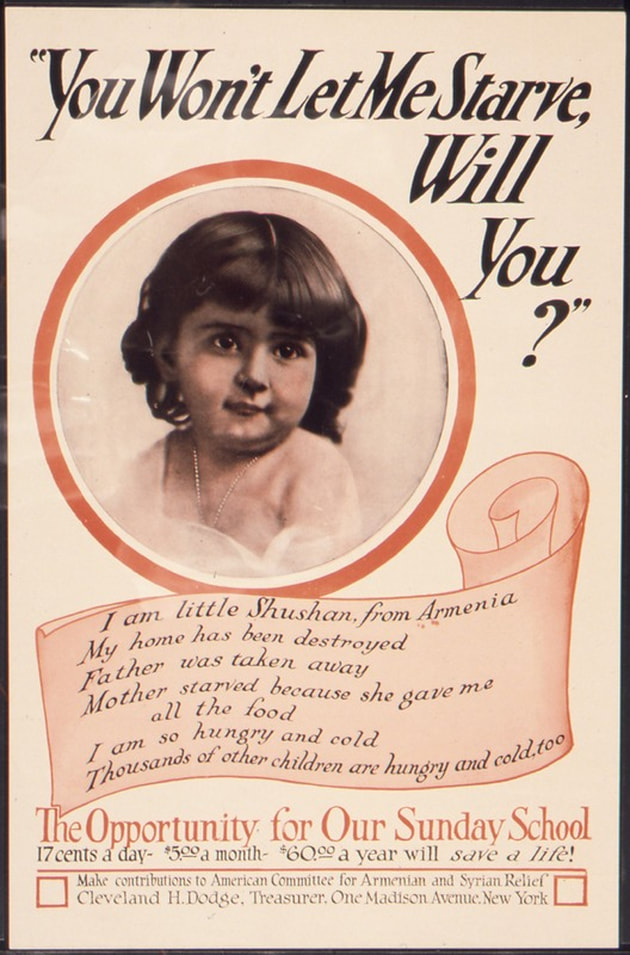

In the above poster, "You Won't Let Me Starve, Will You?" "Little Shushan" says, "My home has been destroyed. Father was taken away. Mother starved because she gave me all the food. I am so hungry and cold. Thousands of other children are hungry and cold, too." Directed specifically at Sunday Schools and children to raise funds for the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian relief, this poster is just one of the appeals made to Americans for charitable support for war-torn regions of Europe and the Middle East. Americans in 1915 were intensely aware of the actions of the Ottoman Empire as it was widely covered by newspapers. Like many campaigns that used starving children in Belgium to raise relief funds or exhort Americans to change their eating habits, Near East Relief and Armenian and Syrian Relief efforts were undertaken as charitable endeavors. The United States never declared war on the Ottoman Empire, perhaps at the behest of relief organizers. But without military intervention, the genocide continued as late as the 1920s. Armenians were Orthodox Christian in a predominantly Muslim Turkish empire. Russia, Turkey's enemy, was also predominantly Orthodox Christian at the time, meaning Armenians were largely branded a "fifth column" of seditious enemy spies living within the borders of the empire. This attitude was exacerbated by the Battle of Sarikamish, in which the Ottoman forces attempted to invade Russia between December, 1914 and January, 1915. Unprepared for the winter weather, the Ottoman military lost more than 60,000 men in a resounding military defeat. In retreat, the Ottomans indiscriminately burned, looted, and massacred Armenian villages near the border. The Ottoman military commander blamed the Armenians for the defeat, saying they had sided with the Russians. This set off a whole host of anti-Armenian violence, despite the fact that many Armenian men had enlisted in the Ottoman military. By the spring of 1915, the Ottoman Empire had launched a campaign of extermination against the Armenians. The lucky ones were able to escape. The not so lucky ones were systematically massacred or sent on forced death marches. The few Turkish politicians who protested were threatened with assassination. Any Muslim caught harboring an Armenian was threatened with execution. Many Armenian men who were massacred were rounded up and taken away from their villages to be killed. So many bodies were dumped in the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that the corpses clogged the waterways and had to be disposed of with explosives. The pollution caused disease for communities living downstream, even after the war was over.

Although charitable organizations worked in the "Near East" throughout the war, and Americans did donate thousands of dollars toward food and relief work, the brutality continued. Coinciding with the massacres of men, Armenian women, children, and the elderly were sent on forced marches into the Syrian desert, punctuated by violence. Those few who survived to arrive at camps after marching without food or water, saw their children sold to childless Muslim families, and the women systematically raped. Those who survived to 1916 and 1917 were ultimately also massacred, so the Empire could avoid freeing them after the war. In all, more than 90% of the Armenian population in the Ottoman Empire was killed or deported, a number scholars estimate at between 1.5 and 2 million people.

The "Lest They Perish" poster above illustrates an Armenian (or possibly Syrian) woman with a child on her back standing in the midst of a bombed-out village. Despite the best efforts of the charitable organizations trying to help Armenians, most of them did, indeed, perish.

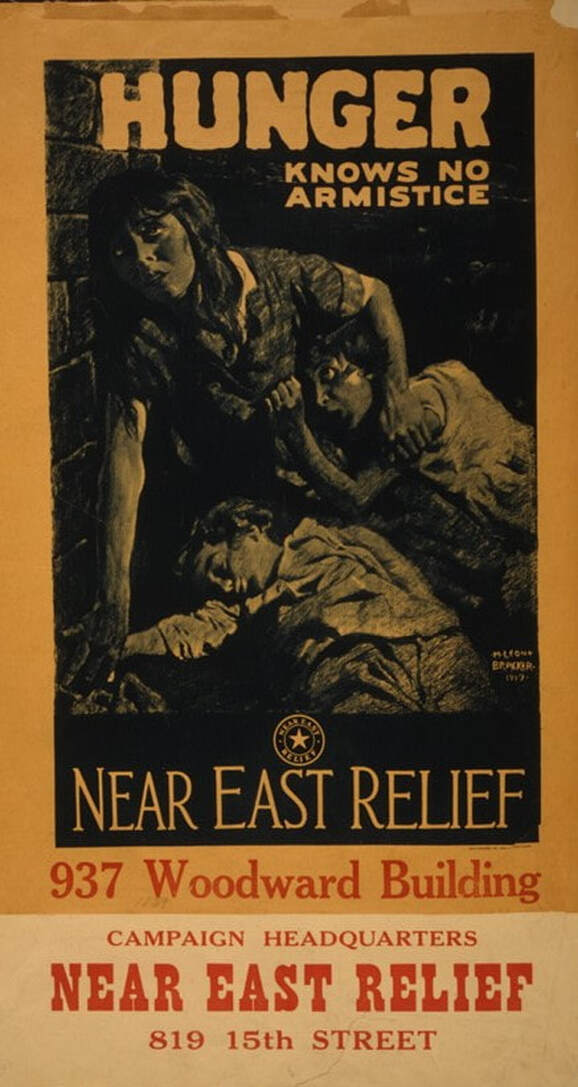

The use of hollow-cheeked women and children in war-torn regions was designed to pull on the heartstrings (and pockets) of Americans of all ages and backgrounds. Propaganda posters by charities like Near East Relief began in 1915 and continued until after the war, along with the genocide. Government-sponsored killings largely ended by 1917, but massacres continued on and off and widespread starvation threatened those who had managed to survive. This poster, "Hunger Knows No Armistice," succinctly points out that starvation was the post-war threat.

Near East Relief was founded in 1915 in Syracuse, NY as the American Committee on Armenian Atrocities, in reaction to reports from Henry Morgenthau, Sr., who was serving as American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Morgenthau was a German-born Jew appointed by Wilson to serve as ambassador in 1913 - a position he initially refused because of Wilson's idea that Jews were well-suited to serve as a bridge between Christians and Muslims. He ultimately accepted the position, and although his work at first consisted mostly of protecting Jewish residents and Christian missionaries, he was soon absorbed by the plight of Armenians in the Empire. Despite his frequent reports of genocide and violence against civilians, the United States remained officially neutral. Frustrated by the Turkish government's refusal to stop the killings, and by the American policy of non-interference, Morgenthau resigned in 1916. In 1918 he published Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, an accounting of his conversations with Ottoman officials about the genocide. However, during his tenure as Ambassador, he was the primary contact for the organization that would become Near East Relief, and was in charge of disbursing charitable donations in Turkey. After his 1916 resignation, it is not clear who disbursed funds, but fundraising continued. In 1919 the committee became only the second charitable organization in American history to receive a Congressional charter. The American Red Cross had been the first. And although charitable efforts continued, they could not stem the tide of genocide. The following video from Facing History & Ourselves, outlines the work of Morgenthau, the Committee on Near East Relief, and the American response (or lack thereof) to the Armenian genocide.

Near East Relief continued their work, focused largely on rescuing Armenian orphans and housing and educating them in a complex system of orphanages inside and outside of Turkey. In 1922, with the burning of Smyrna, Near East Relief evacuated 22,000 children into neighboring states. Evidence suggests that Greek and Armenian neighborhoods in Smyrna may have been purposely set alight by Turkish soldiers. The Muslim and Jewish quarters remained undamaged by the fire. Greek and Armenian residents of Smyrna were subjected to additional massacres, rape, and deportation, both before and after the fire.

In 1930, Near East Relief pivoted to become the Near East Foundation, working on education and economic development efforts in the Middle East and Africa. It still exists as a charitable organization today and the Near East Foundation has created a museum and archive about its organizational history and origins in the Armenian genocide. The U.S. Government never declared war on the Ottoman Empire. There was no military intervention. After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the Treaty of Sevres, and subsequent overthrow of Sultanate with the Turkish Revolution, there was an opportunity to create an Armenian state, which Woodrow Wilson had apparently been in favor of. However, his dreams of reorganizing the Middle East were dashed. The new Turkish government and Bolshevik Russia simultaneously invaded and partitioned the old Armenian Republic before Wilson's plan could be implemented. This led to the creation of both the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic and the absorption by Turkey of portions of the former Armenian Republic, confirmed by the 1922 Treaty of Moscow between Soviet Russia and the new Turkish state. Despite ample first-person evidence of the horrific, systematic, and state-sponsored massacres, and the promise by the Allied Nations in 1915 that the Ottoman Empire would be held responsible for crimes against humanity, no one was ever prosecuted. In fact, the lack of consequences for the genocide may have inspired Adolf Hitler's death camps. He wrote, "I have issued the command -- and I'll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad -- that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy. Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formations in readiness -- for the present only in the East -- with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?" The rapid fall of the Ottoman Empire following the war likely played a major role in the lack of prosecution, as politicians were killed or dispersed and official evidence destroyed. In addition, it took until the Second World War to establish the United Nations and the criminal court at the Hague. Even so, international recognition of the genocide did not formally begin until the United Nations War Crimes Commission published a report in 1948 establishing what constituted war crimes. The Armenian genocide was cited as prime historical example of war crime and crimes against humanity. But it was not until 1985 that the term "genocide" was officially given to the massacres. Most nations did not officially recognize the Armenian genocide until the very late 20th or early 21st centuries. In fact, the United States, which had put so much effort into charitable work and so little effort into military intervention, only just recognized the genocide this year (2021). The Turkish government still refuses to admit to that the actions against the Armenian people during the First World War amounted to genocide. What is left of the Republic of Armenia became an independent state in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union. Today aligned politically and culturally with Europe, Armenians have transitioned fully to a capitalist economy. But their politics, like those of many nations, remain fraught in the modern era. In 2018 anti-government protests, named the 2018 Armenian Revolution, helped usher in political reforms. But other, older conflicts remain, including the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which recently re-erupted in violence in the fall of 2020. A ceasefire was negotiated, and Armenians evacuated, but lasting peace remains elusive. To learn more about the Armenian genocide, visit the Armenian Genocide Museum of America.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

0 Comments

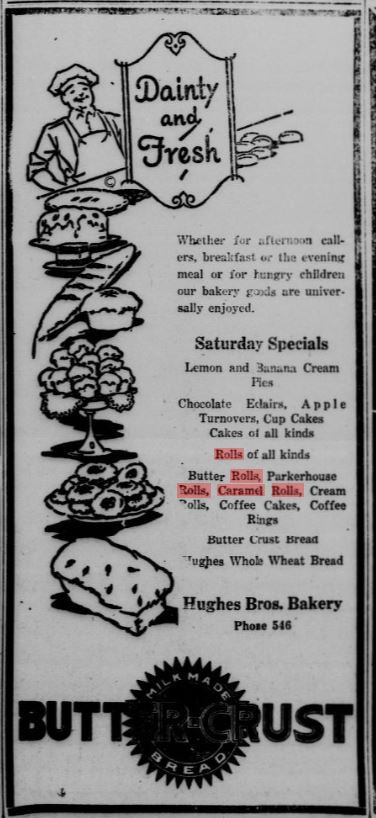

Last week I went home to Fargo, ND for my grandfather's funeral. He had passed away in June of this year, just a few weeks short of his 102nd birthday. Born in 1919, he lived to see a lot of change and ultimately, two global pandemics. It was the first time I had been home since 2019, when I returned for grandpa's 100th birthday and a cousin's wedding. Every time I go home to North Dakota, there's both joy and grief. Joy in seeing old friends and family, in visiting the old stomping grounds, in being able to see the whole sky without too many trees and mountains in the way, and being back in the land where Scandinavian culture still looms large (I went to the Sons of Norway, Kringen Lodge, four times in six days). But also grief, for what once was and will never be again. The common sort of grief when the stomping grounds change almost beyond recognition, but also another sort of grief, of cultural loss. When I was in high school, North Dakota had two Democratic Senators and a Democratic Representative and our biggest exports were wheat, sunflower seeds, honey, and sugar beets. Things have certainly changed since then. But some things haven't changed at all. Case in point: the North Dakota Caramel Roll (pronounced "car-mull," not "care-ah-mel"), formerly called "Dakota Rolls." Once the purview of rural cafes and church basements, the caramel roll is seeing something of a North Dakota renaissance. It's everywhere, and it's amazing. Not to be confused with cinnamon rolls or the sad, dried out, caramel roll cousin, the "sticky bun," caramel rolls are pillowy soft and drenched in smooth caramel. There's nothing worse than getting a caramel roll that's more roll than caramel. The Northeast can keep its dry and sticky buns with burnt pecans. I tried my best to track down the history of "Dakota rolls," but sadly no one else appears to have done the research yet, so this is my stab at it. I think perhaps their prominence in North Dakota has to do with the specific confluence of immigration that makes North Dakota - especially the Eastern half of the state - special when compared to others. Scandinavians, especially Norwegians, abound. Germans, too, but one particular group, Germans from Russia, have settled on the northern plains, including North Dakota, in higher concentrations than anywhere else in the world. The intersection of Scandinavian and German immigration has meant that North Dakota is home to some prodigious bakers. Cinnamon rolls are thought to have originated in Scandinavia, possibly Sweden. They were also historically popular in Germany, where the sticky bun or "schnecken" (snail) is from. Honey-sweetened buns date back to ancient Rome, but the idea to roll the dough flat, spread it with a filling, and roll it into a spiral before slicing was an inspiration whose inventor is lost to time. Caramel rolls specifically seem to date to the early 20th century in North Dakota. I did find a few 19th century references to "sticky buns," but no recipes. The search term "caramel roll" turns up almost exclusively candy advertisements and recipes until the 1920s. I did find one reference to caramel rolls from the Hughes Brothers Bakery in Bismarck, ND. Although the bakery itself predates 1911, they moved to a new location that year, and apparently began engaging in regular newspaper advertisements thereafter. I love the 1928 advertisement - "Let us do your baking these hot days," and published close to Memorial Day, no less! "Why spend time fussing about doing your own baking when we can and will gladly do it for you at less cost than you can do it yourself?" Why, indeed, Hughes Brothers. Why, indeed? Likely coinciding with the rise of diners, roadside cafes, and school cafeterias, the caramel roll expanded across North Dakota (and into some neighboring states, notably South Dakota) with a vengeance. Although there is little mention of them in North Dakota community cookbooks from the 1940s, by the 1970s they're in full evidence. The few recipes that I was able to find are remarkably similar, and all call for making the dough from scratch. But some modern bakers cheat and use frozen bread dough, notably Rhodes brand. My copy of the Westminster Presbyterian Church cookbook from Casselton, ND, undated but likely circa 1970s, judging by the handwriting, has a recipe for "Dakota Rolls" submitted by Mrs. William L. Guy. Mr. William L. Guy was governor of North Dakota from 1961-1973, and the Mrs. was Elizabeth "Jean" (Mason) Guy, who is credited with helping revive the Democratic Nonpartisan League in North Dakota (thanks for the research tip, Mom!). I've reproduced Jean's recipe in full below. Dakota Rolls Recipe1 c. scalded milk (do not boil) 2 T. butter 2 T. sugar 1 t. salt 1 cake compressed or 1 pkg. granulated yeast 1/4 c. lukewarm water 1 egg, well beaten 3 1/2 c. flour (about) Soften yeast in lukewarm water. Stir and let stand about 5 minutes. Combine milk, sugar, salt and shortening (i.e. the butter) and cool to lukewarm. Stir yeast and add to cooled milk. Beat egg, add to milk and yeast mixture. Gradually stir in the flour to form a soft dough (there should be about 1/2 cup flour left for kneading). Beat until smooth. Turn out on floured canvas or board. Cover with greased wax paper and a damp towel. Let rest for 10 minutes. Knead until smooth and satiny, adding flour as needed. This roll dough should not be too firm. Place dough in a warm greased bowl, turning until all of surface is lightly greased. Cover with greased wax paper and damp towel, and let rise in a warm place (85-90 F) about 1 hour and 45 minutes or until double in bulk. Punch down and let rise again until double in bulk. Turn out on flour dusted canvas or board and roll about 1/4" thick in oblong shape, 8" x 16". Brush with melted butter and sprinkle with 1/4 cup brown sugar. Roll as for cinnamon rolls. Cut in 1" slices. Combine 1 C. of brown sugar, 2 T. light corn syrup, and 1 T. butter. Heat slowly in a greased shallow pan or muffin tin. Set aside to cool. Place rolls, cut side down, over the mixture. Cover, let rise until double in bulk. Bake in 375 F oven for 25 minutes. Remove from pan. Cool, bottom side up. Makes 2 dozen rolls. It seems to me that this recipe, while very instructive in terms of the dough, has not nearly enough caramel to cover two dozen rolls. Modern cooks usually combine brown sugar and heavy cream, or some even swear that melted vanilla ice cream is the secret to good and ample caramel. However, the 1975 Fargo-Moorhead Centennial Cookbook also has a recipe for Dakota Rolls, submitted by Judy Adams, which appears to be lifted almost verbatim from the Casselton cookbook. Here's a more caramel-y modern recipe. Sadly, I haven't had time to test this recipe and it's been too hot to bake lately, but fall weather is coming! So maybe a weekend of yeast baking is in order soon. Perhaps I'll combine my caramel roll baking with orange rolls - another Midwestern specialty that seemed to be more prominent in the 1930s and '40s than their caramelly cousins. I'll leave you with one of the few photos I took at home - sunset on Tamarack Lake in Minnesota. And if you're ever in Fargo, try the rhubarb caramel rolls (yes! they put rhubarb in the bottom with the caramel! It's amazing!) at Kroll's Diner. They're divine. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed