|

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase any of the listed books, you'll help support The Food Historian!

A friend of mine is a retired librarian from New York University. A few weeks ago he told me a fascinating story - in the 1970s, in order to make room in the library for new works, the powers that be at NYU decided to get rid of all the master's theses in the library collection. Master's graduates who were still alive and with addresses on file were contacted and asked if they would like their originals. Some departments saved works they thought were important. But most were destined for the dumpster.

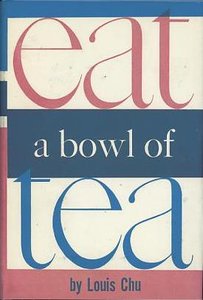

A young librarian had been hired specifically to dispose of the collection. One day, someone walked in off the street, pulled a typed thesis off the shelf, handed it to the that librarian, and said, "This is an extremely important work, please don't throw it out," and walked away. That librarian kept that thesis, and when she quit at the end of the depressing project, she passed it onto my friend, who tucked it way in his desk drawer. Almost a decade later, in the 1980s, he happened to be walking by the circulation desk when a "rookie librarian" was dealing with a request to see a Master's thesis for the first time. "Isn't that right? All the MA theses were thrown away?" she asked him. My librarian friend started to say, "Yes that's right," and the he looked at the index card the researcher had handed over, and added, "except for the one you are looking for, which is in my desk." Rumors of this particular thesis had been swirling among scholars for years, which was how the researcher knew exactly what to request, despite the fact that it was not listed in the library catalog. That work was "The Chinese Restaurants in New York" by master's student Louis H. Chu, which he completed in 1939, along with his Master's degree in Sociology. It WAS an extremely important work - it cataloged Chinese restaurants in New York City at a time when people didn't seem to care much about food history, or about Chinese America. Chu's thesis was largely forgotten. He is better known for going on to write the groundbreaking novel, Eat a Bowl of Tea (1961), which was set among the lives of unmarried Chinese immigrant men in New York City's Chinatown. Although it was not a critical success at the time, it found greater acclaim in the 1970s. In 1989 it was made into a film. It is still cited as one of the most influential works of Asian-American literature.

In addition to his book, Chu also hosted a long-running radio program of Chinese music, and in 1961, he appeared as the mystery guest on the popular television show, "What's My Line?" as part of a promotion for Eat a Bowl of Tea.

"The Chinese Restaurants of New York," however long it languished in that fateful desk drawer, did go on to influence of a generation of researchers of the Chinese-American experience. The thesis is cited in at least twelve subsequent works, including influential recent books like Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America by Yong Chen (2016), Eating Asian American: A Food Studies Reader (2013), and Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family Restaurants by John Jung (2010).

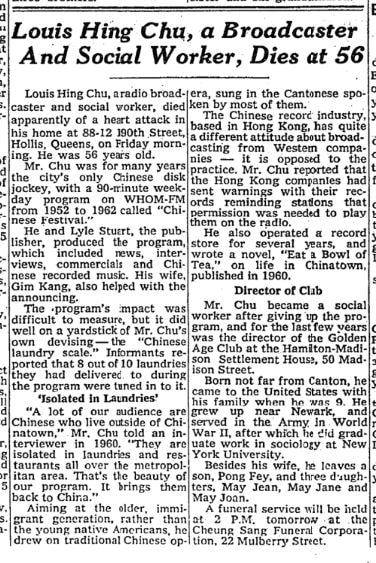

Louis Hing Chu died at home in Hollis, Queens of an apparent heart attack on Friday, February 27, 1970. He was just 56 years old. His obituary focuses on his work as a disc jockey for WHOM-FM, where he played Chinese music for a 90 minute show called "Chinese Festival," which aired on weekdays between 1952 and 1962. Here's the full text of the obituary, "Louis Hing Chu, a Broadcaster and Social Worker, Dies at Age 56," published in the New York Times on March 2, 1970:

Louis Hing Chu, a radio broad caster and social worker, died apparently of a heart attack in his home at 88‐12 190th Street, Hollis, Queens, on Friday morning. He was 56 years old. Mr. Chu was for many years the city's only Chinese disk jockey, with a 90‐minute week day program on WHOM‐FM from 1952 to 1962 called “Chinese Festival.” He and Lyle Stuart, the publisher, produced the program, which included news, inter views, commercials and Chinese recorded music. His wife, Gim Kang, also helped with the announcing. The program's impact was difficult to measure, but it did well on a yardstick of Mr. Chu's own devising— the “Chinese laundry scale.” Informants reported that 8 out of 10 laundries they had delivered to during the program were tuned in to it. ‘Isolated in Laundries’ “A lot of our audience are Chinese who live outside of Chinatown,” Mr. Chu told an interviewer in 1960. “They are isolated in laundries and restaurants all over the metropolitan area. That's the beauty of our program. It brings them back to China.” Aiming at the older, immigrant generation, rather than the young native Americans, he drew on traditional Chinese opera, sung in the Cantonese spoken by most of them. The Chinese record industry, based in Hong Kong, has quite a different attitude about broad casting from Western companies — it is opposed to the practice. Mr. Chu reported that the Hong Kong companies had sent warnings with their records reminding stations that permission was needed to play them on the radio. He also operated a record store for several years, and wrote a novel, “Eat a Bowl of Tea,” on life in Chinatown, published in 1960. Director of Club Mr. Chu became a social worker after giving up the pro gram, and for the last few years was the director of the Golden Age Club at the Hamilton‐Madison Settlement House, 50 Madison Street. Born not far from Canton, he came to the United States with his family when he was 9. He grew up near Newark, and served in the; Army, in World War II, after which he did graduate work in sociology at New York University. Besides his wife, he leaves son, Pong Fey, and three daughters, May Jean, May Jane and May Joan. A funeral service will be held at 2 P.M. tomorrow at the Cheung Sang Funeral Corporation, 22 Mulberry Street. Sadly, Chu died before his novel became more widely respected. And neither NYU nor UCLA, which holds the only other copy of his thesis, have ever seen fit to digitize "The Chinese Restaurants of New York," which seems a shame, given how influential it has gone on to become. I, for one, am just grateful to that unidentified person who knew the work well enough to try to save it, and for the librarians who did. My librarian friend updated me that he tried to request the original thesis, which is now cataloged, but was told it was "processing," which hopefully means it is being digitized, so it won't ever be at risk of destruction again.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

5 Comments

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed