|

During the Second World War, food preservation became a national mandate. I've featured canning-related propaganda posters before, but I thought now would be a good time to feature a few of the lesser-known posters. The above poster is from fairly late in the war. It reads "Grow More, Can More... In '44 - Get your canning supplies now! Jars, Caps and Rings." A special seal featuring a hand (presumably Uncle Sam's) holds a basket containing the words, "Food Fights for Freedom" with "Produce and Conserve" and "Share and Play Square" above. It features a rosy-cheeked young woman in an overtly feminized take on the Women's Land Army overalls, a straw hat tilted fashionably far back on her head, and wearing spotless white work gloves. With a hoe tucked in one elbow and a thumb in her overall strap, she gestures with her free hand at an enormous set of glossy clear glass canning jars, expertly filled with whole tomatoes, halved peaches, green beans, sliced red beets, and what might be whole apricots, yellow plums, or yellow cherries, it's tough to tell. The jars feature a variety of lids, including the new aluminum screw-tops, a glass-topped wire bail with a rubber seal, and a zinc screw top with a rubber seal, illustrating the range of canning technologies still in use. The poster is photorealistic and is probably a literal cut-and-paste of actual photographs - a new technique in an era still dominated by illustrations. It's not clear exactly when this poster was released, but it's likely it was early in the season. The poster exhorts the reader to "grow more" in addition to canning more in 1944, which seems to indicate a spring release, despite the prominence of the large glass canning jars. In addition, the poster warns to stock up on canning supplies now, instead of later in the season. When aluminum was short and factories that made glass were used to produce war materiel, it was easier to make smaller quantities over a longer period of time. By planning ahead, home gardeners and canners could also make sure they had enough supplies on hand to handle an increase in garden produce. Things were getting a bit desperate in 1944 - the war was not going well and the prospect of another long year of war was troubling to ordinary Americans. Rationing had ramped up fully in 1943, and as the war dragged on home canned foods took on more importance in everyday nutrition. For many, especially children, the war must have seemed unending. Little did they know that on June 6, 1944, the United States would launch Operation Overlord - also known as the invasion of Normandy - which would become known as D-Day. D-Day would turn the tide of the war in favor of the Allies, but it would still take another fifteen months for the war to end entirely. Until then, rationing continued and Americans were urged to grow and preserve as much food as they could to supplement their rations. The war finally ended in September of 1945, and by December, rationing of every food except sugar had ended. Foods canned in 1944 would have been important support for rations, but foods canned in 1945 would have been less crucial. One wonders how many home canned foods made it to the end of 1946? We may never know. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join now for as little as $1/month.

Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

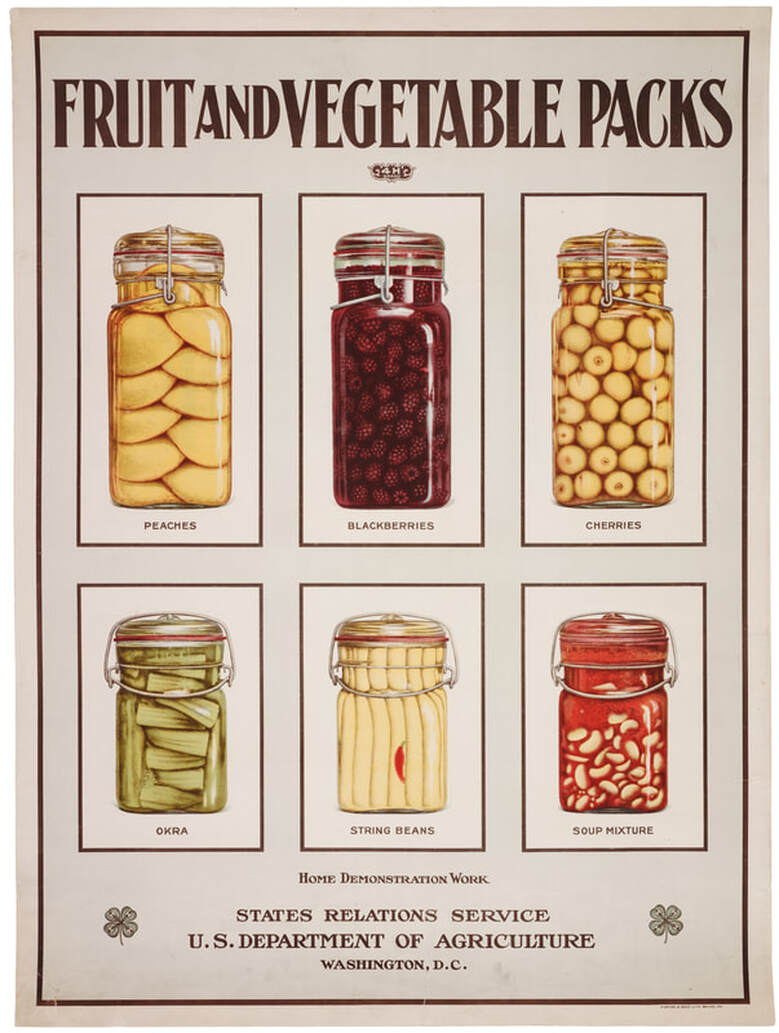

Home canning was promoted as essential to the war effort in both World Wars, but the First World War introduced ordinary Americans to a lot of research on the effectiveness and science of home canning. Although safe canning was still in its infancy (water bath canning low-acid vegetables was still sometimes recommended by home economists at this time, which we now know is not safe), approaching it with a scientific method was new to most Americans. This particular poster's purpose is unclear. Perhaps it was meant to demonstrate the best method of fitting fruits and vegetables into the jars. It is certainly beautiful. The unknown artist illustrated the clear glass wire bail quart and pint jars beautifully. Three quart jars are across the top containing perfectly layered halves of peaches, whole blackberries, and white Queen Anne cherries. Three pint jars across the bottom contain trimmed okra stacked vertically and horizontally, yellow wax beans (labeled "string beans"), which may have been pickled as a tiny red chile pepper can be seen near the bottom of the jar, and "soup mixture" containing white navy or cannellini beans and a red broth that likely contains tomatoes. Wire bail jars work by using rubber gaskets in between the glass jar and a glass lid to get the seal, held in place by tight wire clamps. Although beautiful, they are not recommended today for safe canning. They do, however, make effective and beautiful storage vessels for dry goods like flour, dried beans, spices, dried fruit, etc. (I recommend storing nuts in the freezer to prolong freshness.) Glass wire bail jars were common in the 1910s for home canning and became particularly important for the war effort as aluminum and tin became scarce due to their use in commercial canning and in wartime manufacturing. The poster interestingly includes vegetables in wire bail jars and even bean soup, which is not generally recommended to be canned with the water bath method. If the beans were pickled, they could be safely water-bath canned, but other low-acid vegetables like okra (unless also pickled) need to be pressure-canned to prevent the growth of botulism, a deadly toxin that can survive boiling temperatures. Although pressure canners existed during WWI, they were not in widespread use as they required the purchase of specialized equipment. Community canning kitchens were developed in large part to help housewives share the cost (and use) of more expensive equipment like pressure canners, steam canners, etc. This poster is from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and is labeled "Home Demonstration Work," which indicates it may have been used by home demonstration agents, or trained home economists hired by the USDA, cooperative extension offices, or local Farm Bureaus to train housewives in best practices for home management, including food preparation and preservation. Home demonstration work was in its infancy during World War I, and expanded greatly after the war. What do you think the purpose of this poster is? Share in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

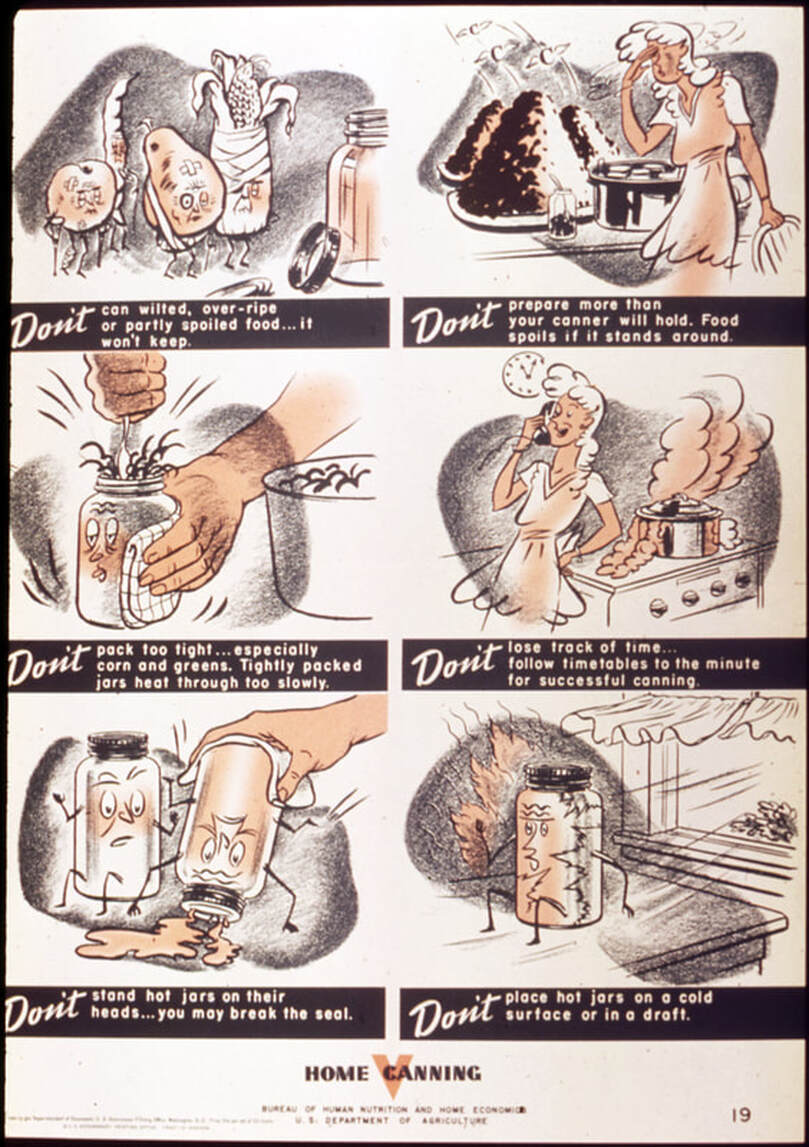

It's prime canning season! If you're facing a glut of tomatoes or more than ready for apple picking so you can make your own sauce, this post is for you. During both World Wars, home food preservation was vital to freeing up supplies of commercially canned goods for feeding soldiers and the Allies. But not everyone was used to canning at home, and even those who were experienced sometimes relied on unreliable or dangerous methods. For instance, my great-grandmother oven canned, which is no longer considered safe. And some folks still try to turn their jars upside down for a seal, which is not recommended. All canned foods work by creating a sterile vacuum seal. High-acid foods like fruit, tomatoes, and vinegar pickled foods can be canned in a water bath, where boiling water (212 F) kills bacteria and seals the jars. Low-acid foods like non-pickled vegetables and meats need to be pressure canned. The pressure canner increases the pressure inside the chamber, which allows water to boil at a much higher temperature. This kills all bacteria, including deadly botulism, and makes the low-acid foods safe to can. One of the ways home economists and the federal government tried to educate people about canning and food safety was through propaganda posters like this one. Here's the advice from the poster: "Don't can wilted, over-ripe or partly spoiled food... it won't keep." If you wouldn't eat it fresh, you shouldn't can it. Although lots of rhetoric during the war was about saving food and preventing waste, canning can only preserve, not restore the quality of food. Poor-quality ingredients makes for poor-quality canned goods, wasting time and effort. "Don't prepare more than your canner will hold. Food spoils if it stands around." Canning takes time, and leaving cut fruits or vegetables lying around waiting to be put into jars makes them more susceptible to collecting bacteria or spoiling. Canning depends on sterile jars and fresh ingredients. Although it can be tempting to work ahead, time your work carefully to avoid waiting. "Don't pack too tight... especially corn and greens. Tightly packed jars heat through too slowly." Canned goods need to be heated through entirely to create a proper vacuum seal and prevent the growth of bacteria. Especially for low-acid foods like corn and greens, proper heating is essential to successful canning. Tightly packed jars not only risked spoilage, they also wasted fuel as it would take them longer to heat through, if at all. "Don't lose track of time... follow timetables to the minute for successful canning." We've all been there. That's what kitchen timers are for. While over-cooking doesn't usually hurt, under-cooking can result in improper seals. Better to use the timer and be sure. Test kitchens and home economists and scientists developed the time tables to ensure a minimum amount of time in the boiling water bath or pressure cooker to ensure adequate seal and food safety. "Don't stand hot jars on their heads... you may break the seal." Although some people still do this to "ensure a good seal," a heat seal is not the same as a vacuum seal, and liquids touching the tops of the cans before they are fully cooled may break the seal and allow air and bacteria in, leading to spoilage. "Don't place hot jars on a cold surface or in a draft." They may break or explode. Seriously. This is also why canning jars need to be heated before filling - not only for sterilization, but also to prevent shock and cracks or breakage. Canning can be intimidating, and certainly time-consuming, but the push to get Americans to participate in home food preservation was a hard one. Although it can be difficult to balance the effort of canning with modern lives, the urgency of food preservation during World War II meant people carved out the time to make the effort. Do you can at home? I usually don't have the time, although nothing beats home canned applesauce (at least, my mom's style) and jam. A friend of mine keeps me supplied with amazing homemade jams. They're worth every penny. Especially since then I don't have to do the canning myself! Share your canning memories and stories (or horror stories) in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

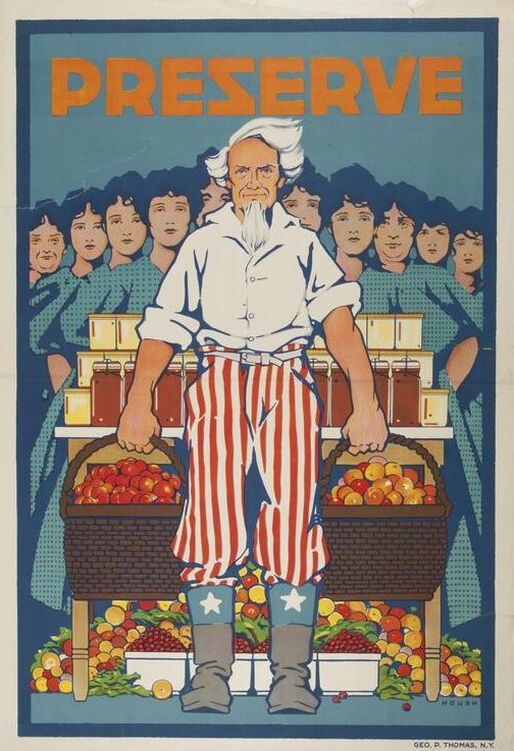

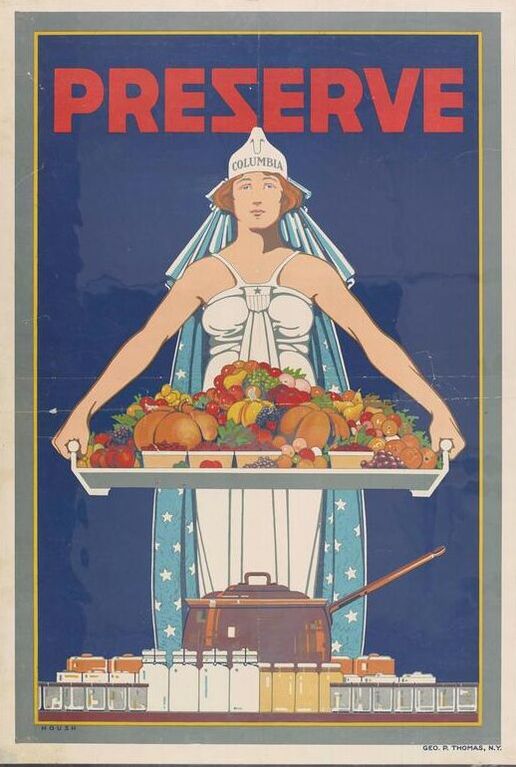

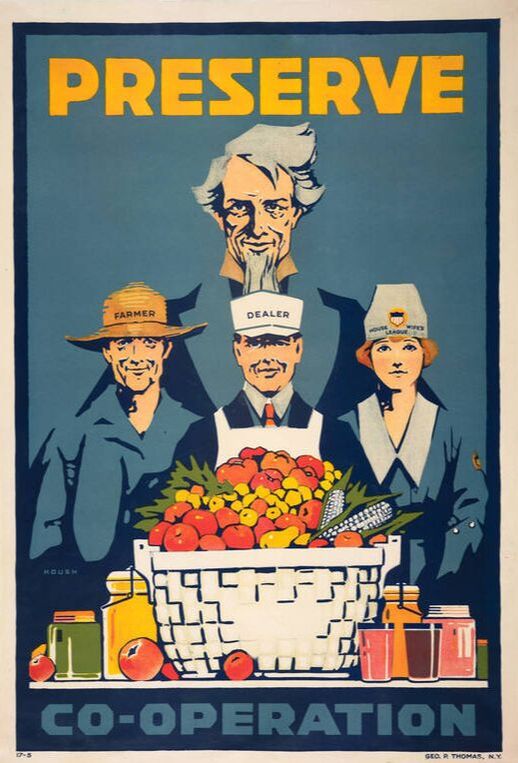

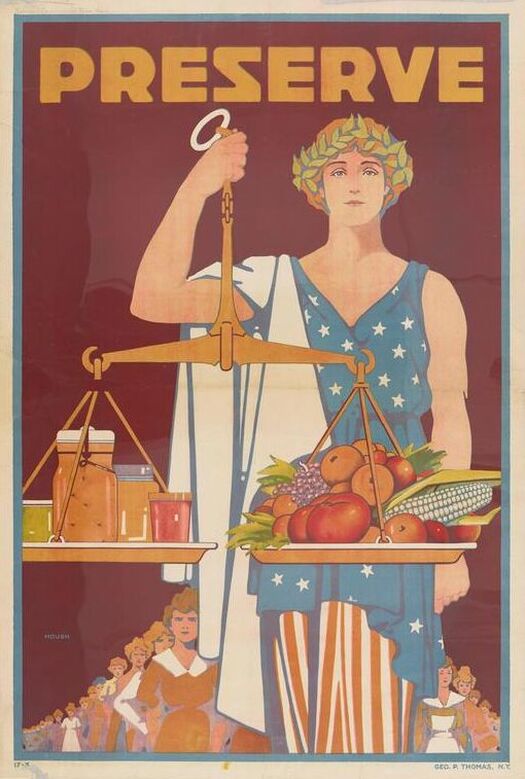

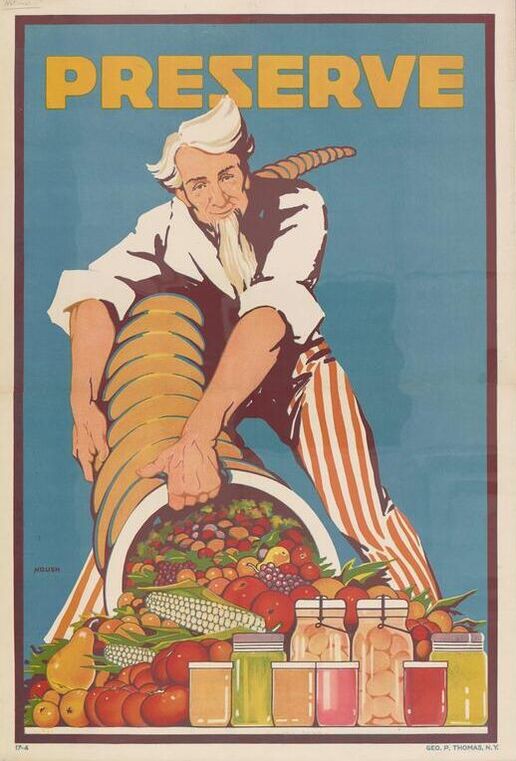

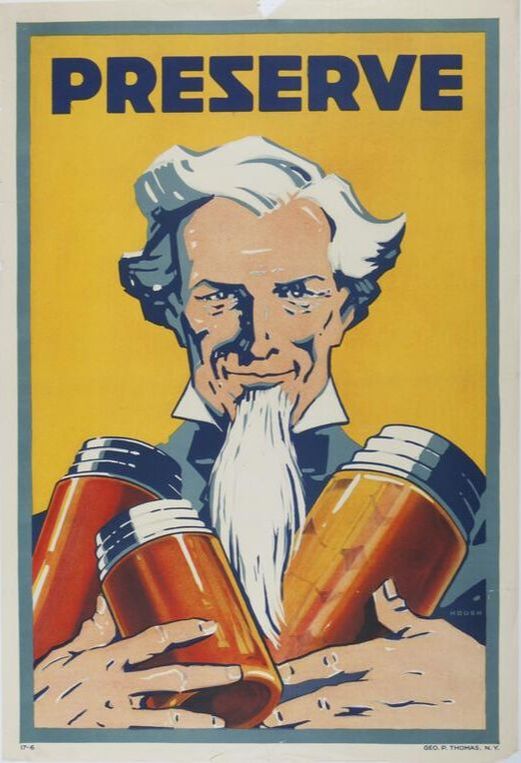

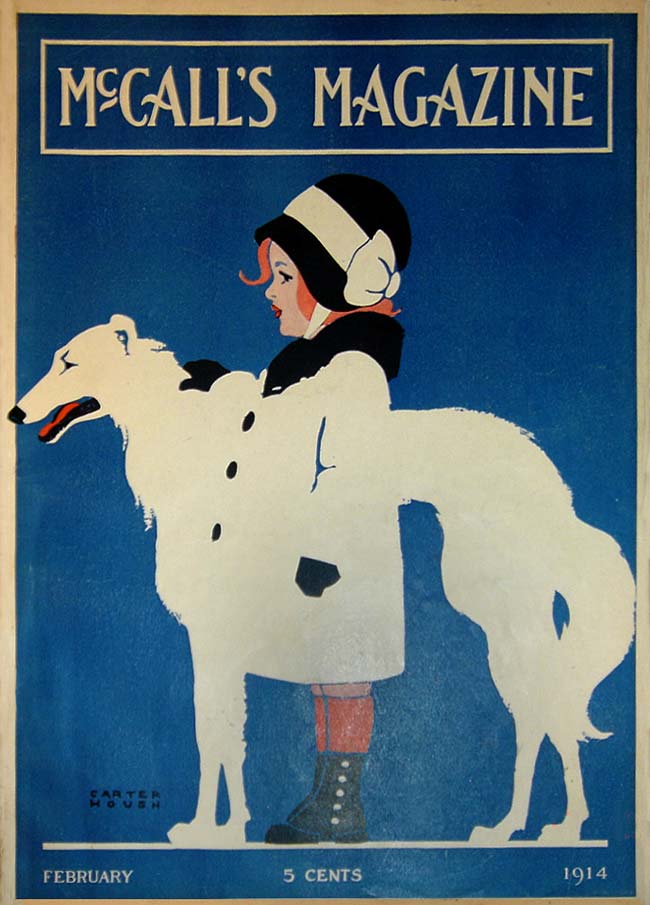

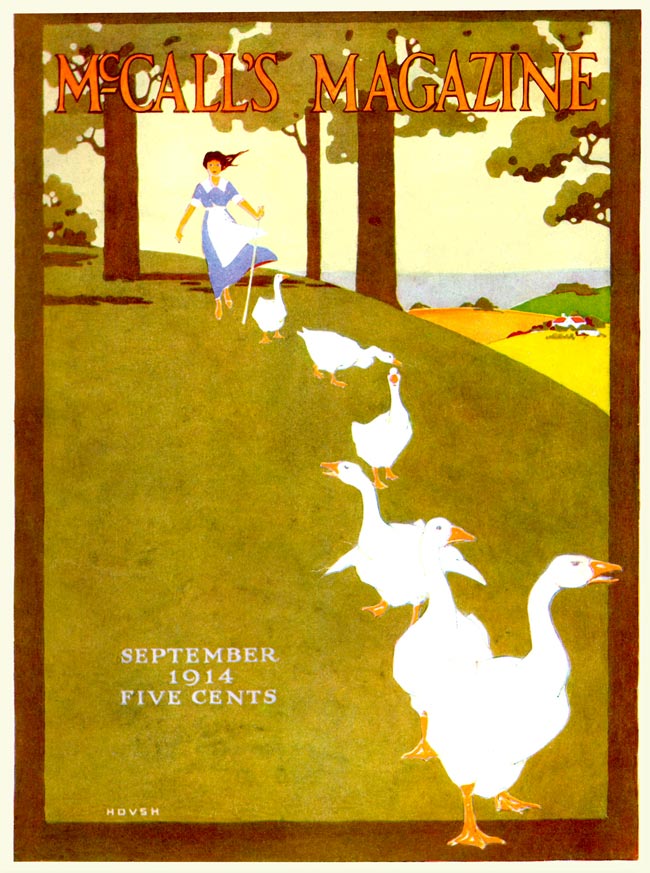

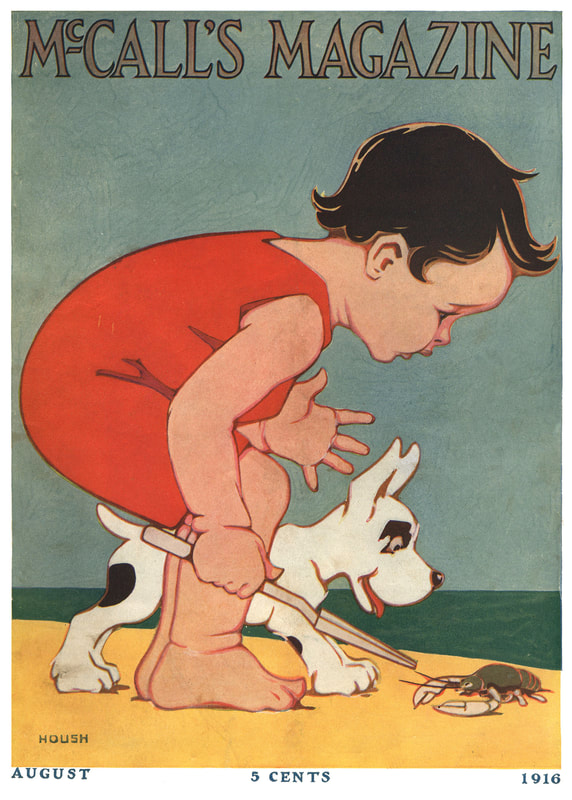

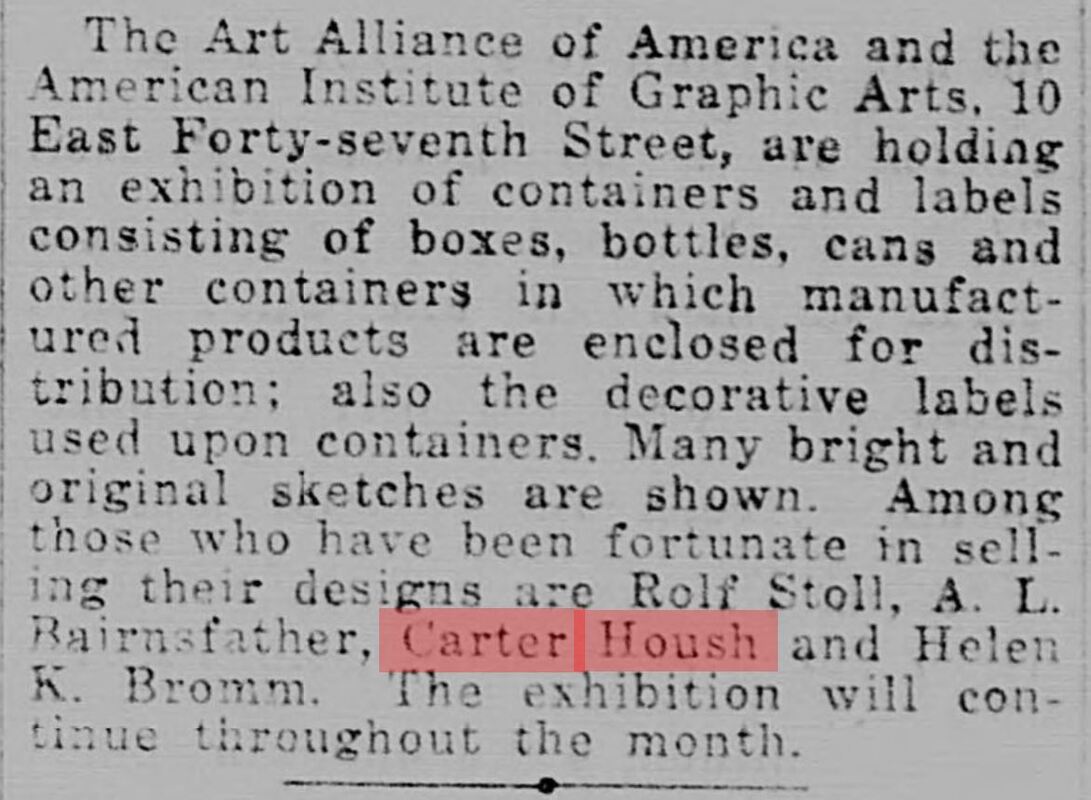

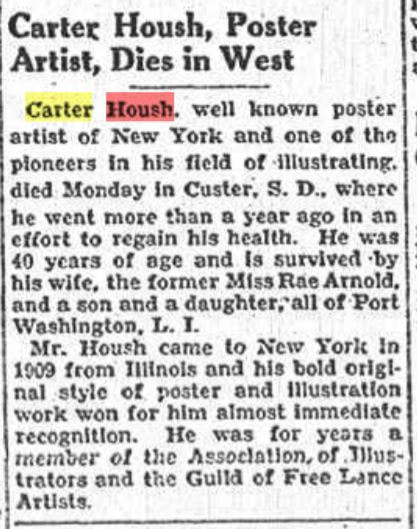

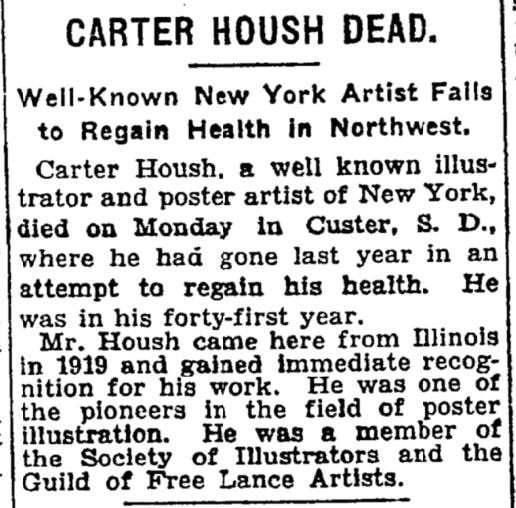

Note: This article was originally published on February 12, 2020 and has been updated with new information! If you haven't figured it out by now, I really love propaganda posters. Especially those from World War I. But my absolute favorite poster artist is one no one seems to know anything about.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, Uncle Sam, in his trademarked striped trousers but without his blue frock coat stands in his shirtsleeves, rolled up to the elbow, holding baskets full of fruit. Behind him is a table laden with full canning jars, with fruit and vegetables overflowing a pile beneath the table and behind that an army of women all dressed in blue. Missouri Historical Society. Carter Housh was apparently born in 1887 and died in 1928. And aside from an illustration or two for McCall's magazine, he is known ONLY for these six propaganda posters, encouraging Americans to preserve food during the First World War.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, a white-clad Columbia, goddess of America, with her French liberty cap and a star-spangled cape holds a massive tray laden with fresh fruits and vegetables. Below, an enormous handled saucepan and empty jars lined up before her, ready for filling. USDA Library Archive. As far as I can tell, nowhere else on the internet are all six of these posters displayed together. In fact, three of them were new to me! I discovered them as I was doing research on Housh, so that was delightful.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, Uncle Sam, again in his blue frock coat, looms behind three figures - a farmer in a straw hat, a "dealer" or greengrocer in white cap and apron, and a woman dressed in the official food preservation uniform with a white cap that reads "House Wife's League" stand before him. An enormous white basket of fresh produce, flanked by filled canning jars, sets on the table before them. Underneath reads "Co-operation," implying that preservation needs the cooperation of the farmer, the retailer, and the housewife, all under Uncle Sam's watchful gaze. Missouri Historical Society. Housh's work has been called "modern" before, but aside from the font with it's rather Z-looking S, the imagery and style seems very typical of the period. I love Housh's use of shadow and color-blocking and his depictions of produce are simply divine - perfect, gleaming, and blemish-free. Quite unlike the real world, alas. I particularly enjoy Housh's depictions of people and Uncle Sam is no exception. Uncle Sam was long used to represent the United States, but during the War James Montgomery Flagg's depiction in his famous "I Want YOU!" poster helped lead to a resurgence in use of Uncle Sam to represent the U.S. I'm particularly fond of Housh's version because he's less scrawny and stern looking than other incarnations. Plus, when he's hard at work, shirtsleeves rolled up, his hair gets a particularly nice wild swoop to it. One that isn't present in his more sedate depictions, like the poster below. One interesting thing about this time period is that both Uncle Sam and Columbia were used to represent the United States. The First World War is one of the last times the Greek-inspired secular goddess would be broadly used to represent America.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. In this image, a different incarnation of Columbia, in a gown of star-spangled blue, red and white stripes, with a white draped sleeve and a crown of laurel, holds enormous scales depicting canned goods and fresh produce in balance. Lined up behind her stretching out into the distance is a variety of American housewives in varying dress. USDA Library Archives. As much as I love Uncle Sam, of course I prefer Columbia because she is just so Progressive Era - an inspiring mix of Greco-Roman, feminist, Romantic representation that doesn't exist anymore. Of course, today's American goddess would look quite a bit different, and probably would not be named after Columbus, and that's equally as wonderful. If you want to know more about Columbia, check out this overview from the Atlantic. Which of these beautiful posters is your favorite? And if anyone happens to find anything on Carter Housh (or his printer, George P. Thomas of New York), please send me the info! Update - more about Carter Housh!Apparently Susan Jackson took my request to heart! Here's what she has to say about Carter Housh, her grandfather! Carter Housh was my mother's father. He was married to Rae (Arnold) Housh Enright. He died when my mother, Barbara Belle (Housh) Gibson, was 13. He left due to illness and went out to South Dakota where he died. He also had a son, David Paine Housh, my mother's younger brother. His wife, Rae, remarried another artist, a political cartoonist and author of children's books, Walter J. Enright. I do not have much information on Carter otherwise, sadly, nor do I have a good picture of him (so far.) Thank you, Susan, for sharing this great biographical info! I did do a little more digging to see what else I could find and I did find a few more references, although fewer than you might expect. In 1910 he appeared to work as an illustrator for the Sunday edition of the Buffalo Times based out of Buffalo, New York. He also worked for several years for McCall's magazine between 1910 and 1916, leaving evidence of several magazine covers, courtesy Flickr and Magazineart.org, a delightful website mentioned in one of the Flickr postings. We see no further known references to Carter Housh until 1918, the height of the U.S. involvement in World War I, when he is mentioned in an exhibition of artists as one of the few people who sold designs. 1918 is also the date attributed to his stunningly beautiful "PRESERVE" poster series. The Art Alliance of America and the American Institute of Graphic Arts, 10 East Forty-seventh Street, are holding an exhibition of containers and labels consisting of boxes, bottles, cans and other containers in which manufactured products are enclosed for distribution; also the decorative labels used upon containers. Many bright and original sketches are show. Among those who have been fortunate in selling their designs are Rolf Stoll, A. L. Bairnsfather, Carter Housh, and Helen K. Bromm. The exhibition will continue throughout the month. Carter Housh died on Monday, May 14, 1928 in Custer, South Dakota. Two obituaries in New York newspapers were published, likely due to his connections to New York City and Buffalo, NY when he was an illustrator. One, "Carter Housh, Poster Artist, Dies in West," published in the New York Sun on May 16, 1928 reads: Carter Housh, Poster Artist, Dies in West Another obituary, "Carter Housh Dead," was published in the New York Times, also on May 16, 1928. Carter Housh Dead Clearly the New York Times was less interested in accuracy than the Sun. It is sad to learn his life was cut so short and one wonders what illness he died of. Still, he leaves a legacy of stunning art and his posters remain my favorites of the entire war. If anyone finds any more breadcrumbs, send them my way and I'll update again! And, as always, if you enjoyed this post, please consider becoming a member of The Food Historian. You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

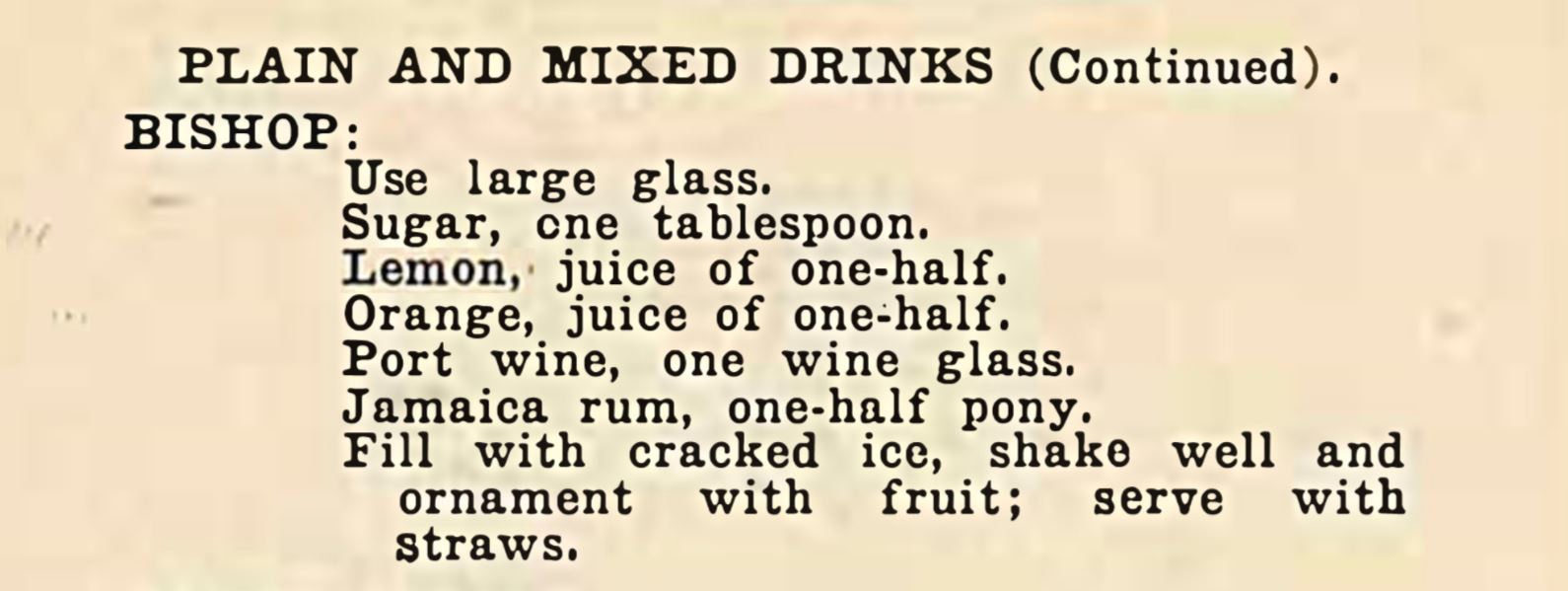

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. Thanks to everyone who joined me on Friday for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, in commemoration of Memorial Day, we talked about its Civil War origins, the history of grave decoration as Decoration Day, cemetery picnics (and picnics in general), history of refrigeration, how food was preserved before refrigeration, including canning, with mention of my book review of Canned, a discussion of fireless cookers/hay boxes, including Sabbath cooking, historical spring (spoiler alert: June used to be spring), book update, including WWI New York City soldiers' canteens, agricultural labor shortages, comparisons between WWI and the coronavirus pandemic, and what I've been reading recently. Bishop Cocktail (1906)I've been looking for a port wine cocktail for a while so that I could crack open my new bottle of Brotherhood Winery's Ruby Port, which is delightful. And, as Anna Katherine pointed out, Friday was Drink Local Wine Night! And Brotherhood Winery - the oldest winery in the country - is located just a few miles from my house. As I mentioned in the video, the Bishop cocktail (notice that the Black Stripe is the very next recipe!) ended up tasting very similar to sangria, which is not a bad thing. But I would definitely cut down on the sugar next time. And having looked it up since the show, Jamaican rum is a dark rum - not at all close to the white Puerto Rican rum I was using. But in a global pandemic, you use what you've got! This cocktail comes from the 1906 How to Mix Drinks: Compiled, Selected, and Concocted by George Spaulding. Here's the original version, with my notes: Use large glass. Sugar, one tablespoons [try one teaspoon instead] Lemon, juice of one-half [or 1 tablespoon bottled] Orange, juice of one-half [or 2 tablespoons bottled] Port wine, one wine glass [ooops! I did a half, you can too] Jamaica rum, one-half pony [1/2 oz.] Fill with cracked ice, shake well and ornament with fruit [I used blood orange]; serve with straws. If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Once again the wheels of publishing grind slowly, but I'm pleased as punch to see one of my book reviews in print again, this time in the Spring 2020 edition of the Agricultural History Journal. Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. By Anna Zeide. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018. 269 pp., $34.95, hardcover, ISBN 9780520290686. Few people these days haven’t tasted canned food, but have you ever considered its origins? Tin cans versus glass jars? The science of safe canning? Anna Zeide did in her new book Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. Tracking the rise of commercially canned foods in America from the condensed milk of the Civil War to modern concerns about bisphenol-A (BPA), Zeide puts canned goods firmly in historical context – connecting them to changes in technology, agricultural science, medicine, politics, and social changes. On the surface, the book is about the safety of canned goods; Zeide studies the roles of lead poisoning, spoilage, botulism, mercury in canned fish, and the 21st century issue of bisphenol-A (BPA) contamination in shaping consumer use of and confidence in canned goods. The chapters are arranged as case studies and are outlined in chronological order. The introduction outlines the history of canning technology (and safety) before moving on to condensed milk in the post-Civil War era and the rise of chemical additives and improvements in canning technology. The chapter on canned peas in the 1910s discusses the relationship between canners, agricultural research, and vertical integration of farming with vegetable varieties bred to be canned, embracing agricultural grading. The chapter on canned ripe olives addresses the threat of botulism in the 1920s, and how the canning industry resisted regulation and attempted to place the blame on careless home canners. The chapter on canned tomatoes in the 1930s outlines how canners resisted grading of canned goods, even as they embraced it for their own suppliers, and attempted to read the mind of “Mrs. Consumer,” now an economic force to be reckoned with. The chapter canned tuna and mercury contamination in the 1970s chronicles the rise of processed food more broadly, the expansion of canners beyond canned food, and the backlash against artificial ingredients, pesticides, and other contaminants in canned goods and industrial food. Finally, Zeide ends with a discussion of consumer fears about BPA in Campbell’s canned soups in the 2010s, and Campbell’s attempts to cover up health concerns even as it tried to appeal to a new, food-savvy generation of consumers. As you can probably tell, beneath the study of the relationship between consumers and food processors is the real meat of the book – on regulation of the industry. At first, early canners were happy to work with government regulators to prove themselves worthy in a crowded and competitive market. And access to agricultural colleges for crop research and federal food safety research were benefits they were only too happy to embrace. But as food processors consolidated and the 20th century wore on, canners became increasingly resistant to government regulation, oversight, and transparency. So much so that by the 2010s when Campbell’s Soup was confronted with consumer concerns about the endocrine disrupting BPA, they closed ranks and denied any safety concerns. But, despite promises to end the use of BPA in can liners and even as it hopped on other bandwagons such as the labeling of genetically modified foods, as of 2016 Campbell’s had yet to replace BPA in their cans. Zeide concludes the book by outlining why government regulation and collective action is more effective in maintaining food safety than the industry’s beloved individual action. Throughout the book, food processors claim that “Mrs. Consumer” can choose for herself which brands are the safest and highest quality, but that ignores circumstances beyond consumer control, such as the case study Zeide cites in which consumers fed on a diet devoid of canned goods and full of locally produced whole foods actually saw their BPA levels increase, likely due to the use of BPA in plastics used as part of the even minimal food processing, such as in the milking industry or in the production of spices in other countries (p. 183). Ultimately, Zeide tries to place canned goods briefly in context in the conclusion – that access to canned fruits and vegetables gave a whole subset of Americans access to nutrients they might not have had access to before, and that emotional responses to the foods of our childhoods will give canned goods longevity. Although at various places throughout the book Zeide makes mention of potential class issues surrounding canned goods, and the assumptions of canners that “Mrs. Consumer” was white and middle class, a more thorough examination of class and race in the context of canned goods would have made this book even stronger, especially considering the emphasis on consumer marketing. However, despite this omission, Canned is ultimately a strong addition to food historiography and I applaud Zeide for her detailed work and her ability to place events and people in context, drawing connections and conclusions that are well supported by her research. If you enjoyed this book review, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content and discounts on programs and classes.

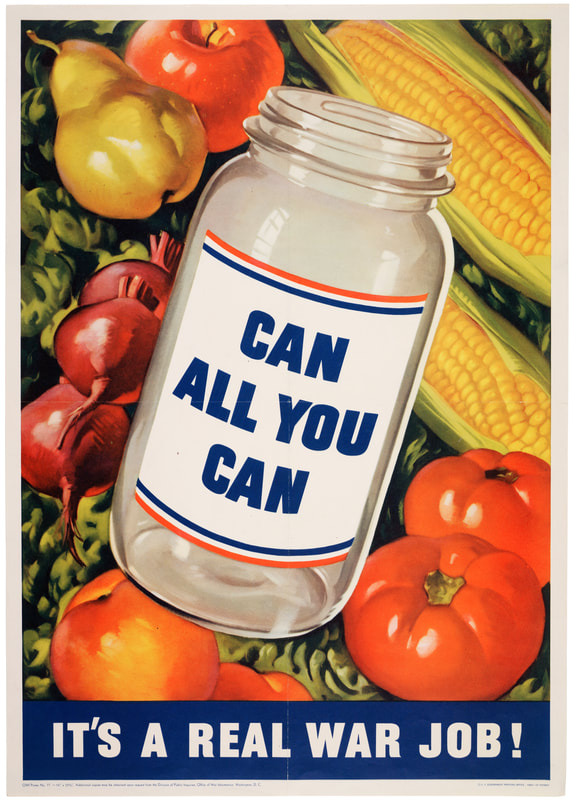

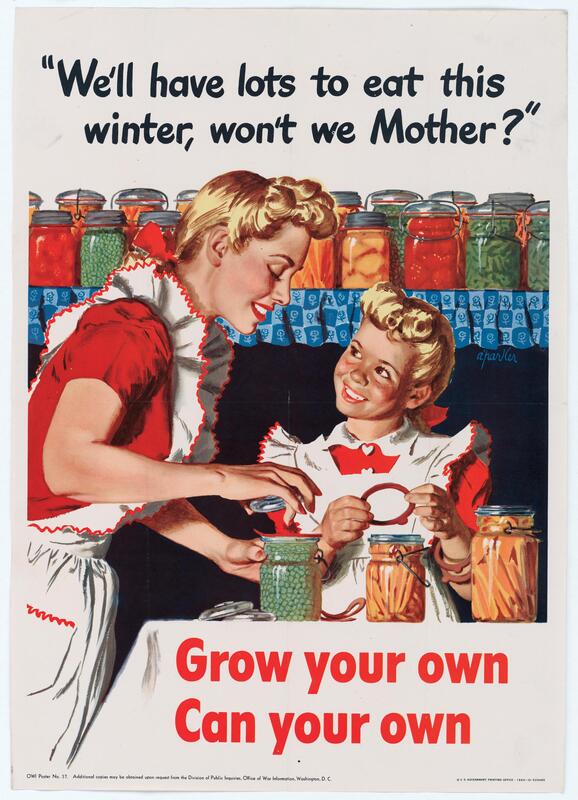

Remember last week's foray into home canning during the First World War? Victory garden and canning efforts returned for World War II. Unlike the First World War, rationing during the Second World War was mandatory and regulated by the Federal government. Because purchased foods were restricted, Americans were strongly encouraged to keep victory gardens. And because commercially canned goods were needed for shipment overseas, ordinary people were encouraged to preserve the fruits of their victory gardens at home. Propaganda posters like the one above made great efforts to frame the drudgery of home food preservation in wartime terms. Housewives were encouraged to "can all you can," while the poster cheerily chirped, "It's a real war job!" presumably to put the kibosh on all the naysayers who insisted otherwise. In addition to being a "real war job," canning efforts were framed in a number of ways. In the above poster, a proud housewife, with perfect victory curls, a ruffly floral apron, and an armful of jars (beets, green beans, and tomatoes from the looks of it, with more beets, raspberries, and corn below) indicates that not only is she preserving food for her own family, she's also "fighting famine." By "canning food at home," she's freeing up commercially canned goods to be sent overseas to help the civilians of war-torn countries stave off famine. In this final poster, a cherubic little girl, in a dress and frilly apron that matches her mother's outfit, helps place the rubber rings on wire bail jars of carrots and peas, preparing them for canning. Hopefully in a pressure canner, since low-acid vegetables like peas and carrots need to be canned at higher than 212 degrees Fahrenheit (boiling point) in order to be safe from botulism. The girl says, "We'll have lots to eat this winter, won't we Mother?" implying that a well-stocked home pantry like the one in the background provided security against future food shortages or tightened rations. Both the promotion of home canning and the implementation of wartime rationing reflected an agricultural system not designed to provide massive surpluses. Coming out of the Dust Bowl era of the Great Depression, agricultural practices in the United States had improved, but most of the food produced at home was still consumed at home. Cuts had to be made domestically in order to free up the food supply for shipment overseas. In the decades since the Second World War, American agriculture has been transformed, both by the leftovers of chemical warfare and explosives production (pesticides and chemical fertilizers come to mind) but also by the mindset that producing unlimited food brings global security. Improvements to global shipping have meant that it is now as easy (or easier, and certainly cheaper) to get garlic from China as it is from the farmer down the street. Or apples from New Zealand or Peru than from a local orchard. Home preservation and home kitchen gardens are certainly no longer necessary, given the world of food at our fingertips at both grocery stores and online. With home food preservation no longer necessary, canning and gardening have taken on a sheen of delight. For many people, it is preferable to can your own jam from berries you picked yourself, rather than buy from the store. But I think the romance that hangs around home food preservation today belies the struggles of the past - when poorly preserved foods or inadequate supplies meant illness and hunger. When a poor harvest didn't just mean higher prices at the grocery store, but threatened real starvation. it's important to remember that food preservation during World War II played an important role in both nutrition and improving the everyday diet of Americans. But it's also important to recognize the amount of labor spent on both victory gardens and home canning at a time when American labor was already stretched thin in the war effort as factories ramped up production and speed, women took on the work of fighting men, and everyone hustled to get things done with fewer people and fewer resources. The size of the United States meant that we never quite had the same threats of deprivation as the U.K., which is perhaps why they are so much better at telling their WWII home front stories than Americans are. The size and scope of our continent meant we could be self-sustaining and still provide food abroad, whereas the United Kingdom had to learn how to do without regular food shipments to its tiny island. So the next time you do some home canning, whether from necessity or for fun, I hope you remember the people of the past. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more!

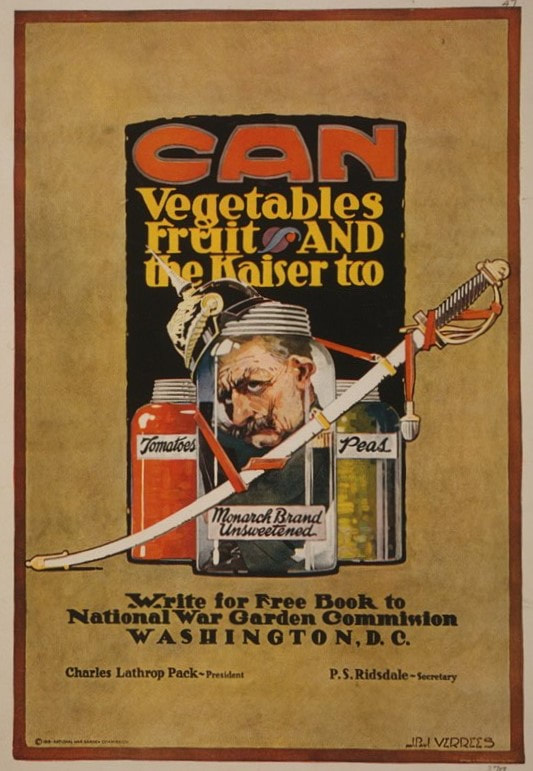

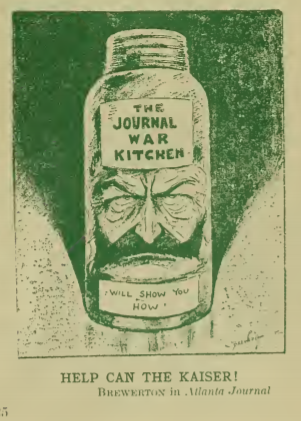

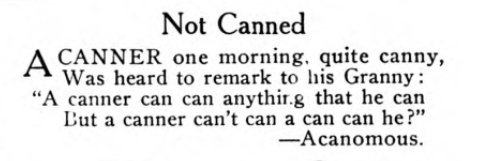

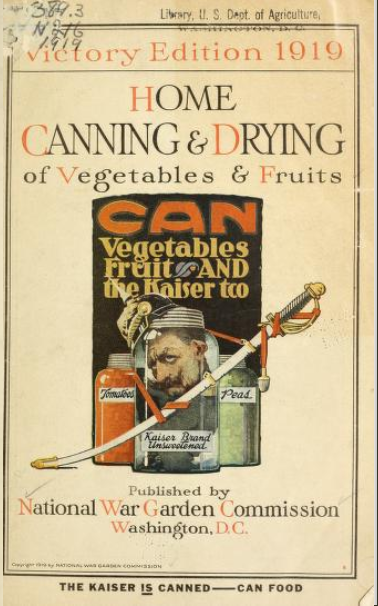

"Can Vegetables, Fruit, and the Kaiser, Too. Write for Free Book to National War Garden Commission, Washington, D.C." September is still preserving time, so I thought the next few World War Wednesdays would be about canning. This is another of my favorite World War I propaganda posters. Developed by the National War Garden Commission, the poster shows glass jars with zinc tops. Tomatoes at left, peas at right, and front and center, the profile of Kaiser Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia. His spiky German helmet and saber hang on the jar, which is labeled "Monarch Brand, Unsweetened." Eminently clever, the poster implies that home preserving has the power to defeat the might of the German Empire and the Kaiser himself. The First World War was one of the first times that ordinary Americans were called upon to preserve food in their homes. Many Americans, especially those in rural areas, were already canning and preserving the bounties of their home gardens. But as commercial canning became increasingly widespread, inexpensive, and safer, people with easy access to food retailers found it much easier to simply purchase canned goods, instead of going through the bother of putting up their own. Many people were still using the tried-and-true, but not necessarily safe, methods of their forebears. And while water bath canning was increasingly outpacing the traditional food preservation methods of fermentation, drying, and sealing jam with paraffin wax, water bath canning low acid vegetables still was not 100% safe. But as the government encouraged food conservation and food preservation, the National War Garden Commission stepped up to the plate. Founded (and funded) by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, the National War Garden Commission published a series of food preservation pamphlets that were used all over the country by home economists and women's groups to encourage home canning. The National War Garden Commission was also behind the school garden movement, but that's another post. The Commission would go on to produce a number of pamphlets on war gardening (renamed "Victory Gardening" post-war, a term that would be revived during the Second World War), including one pamphlet entitled "The War Garden Guyed," published in 1918. A clever play on words ("to guy" someone was to make fun of them, or ridicule), the "Guyed" contained cartoons, poems, and slogans both promoting and making fun of the gardening and food conservation movements. Submitted by newspaper editors, soldiers in the trenches, magazines, and ordinary people, the collection is quite a fun read, and not the only version the National War Garden created. "Raking the Gardener and Canning the Canner" predated "The War Garden Guyed" by one year - published in 1917, a quick turnaround indeed and indicates how quickly ordinary people adjusted to the idea of home gardening and canning. You can view almost all of the National War Garden Commission pamphlets on archive.org. In 1919, the National War Garden Commission used the "Can the Kaiser" poster image again, this time on their revamped "Home Canning & Drying of Vegetables and Fruits," rebranded "Victory Edition" post-war. At the bottom of the cover, it reads, "The Kaiser IS Canned." Although the fervor for home canning, thrift, and self-sufficiency continued into 1919 and 1920, by the time economic prosperity had returned full-force to give us the Roaring Twenties, most ordinary people who took up canning for the war effort abandoned it in victory. But I like to think that many of the food preservation lessons learned during the First World War would be revived and put to good use by the time the Second World War rolled around. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed