|

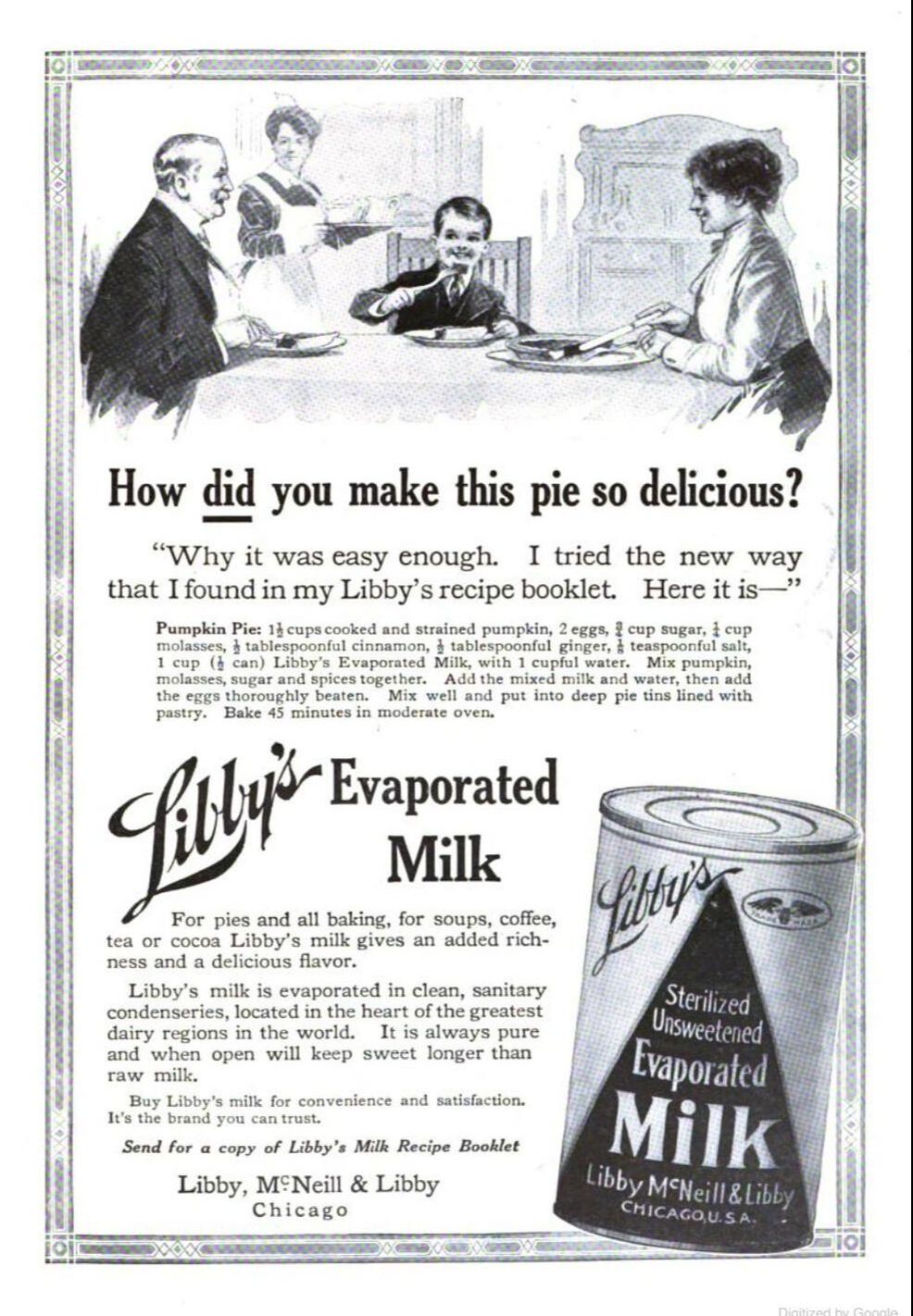

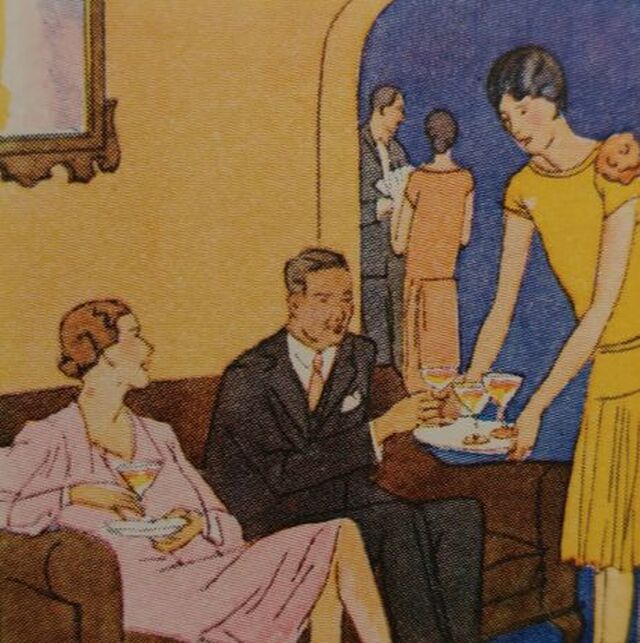

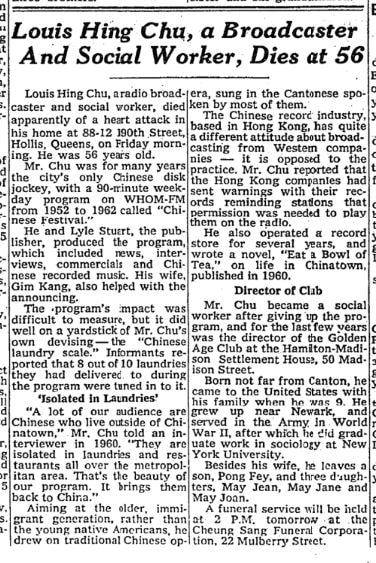

Libby's pumpkin pie is the iconic recipe that graces many American tables for Thanksgiving each year. Although pumpkin pie goes way back in American history (see my take on Lydia Maria Child's 1832 recipe), canned pumpkin does not. Libby's is perhaps most famous these days for their canned pumpkin, but they started out making canned corned beef in the 1870s (under the name Libby, McNeill, & Libby), using the spare cuts of Chicago's meatpacking district and a distinctive trapezoidal can. They quickly expanded into over a hundred different varieties of canned goods, including, in 1899, canned plum pudding. Although it's not clear exactly when they started canning pumpkin (a 1915 reference lists canned squash as part of their lineup), in 1929 they purchased the Dickinson family canning company, including their famous Dickinson squash, which Libby's still uses exclusively today. In the 1950s, Libby's started printing their famous pumpkin pie recipe on the label of their canned pumpkin. Although it is the recipe that Americans have come to know and love, it's not, in fact, the original recipe. Nor is a 1929 recipe the original. The original Libby's pumpkin pie recipe was much, much earlier. In fact, it may have even predated Libby's canned pumpkin. In 1912, in time for the holiday season, Libby's began publishing full-page ads using their pumpkin pie recipe in several national magazines, including Cosmopolitan, The Century Illustrated, and Sunset. But the key Libby's ingredient wasn't pumpkin at all - it was evaporated milk. Sweetened condensed milk had been invented in the 1850s by Gail Borden in Texas, but unsweetened evaporated milk was invented in the 1880s by John B. Meyenberg and Louis Latzer in Chicago, Illinois. Wartime had made both products incredibly popular - the Civil War popularized condensed milk, and the Spanish American War popularized evaporated milk. Libby's got into both the condensed and evaporated milk markets in 1906. Perhaps competition from other brands like Borden's Eagle, Nestle's Carnation, and PET made Libby's make the pitch for pumpkin pie. Libby's Original 1912 Pumpkin Pie Recipe:The ad features a smiling trio of White people, clearly upper-middle class, or even upper-class, seated around a table. An older gentleman and a smiling young boy dig into slices of pumpkin pie, cut at the table by a not-quite-matronly woman. A maid in uniform brings what appears to be tea service in the background. The advertisement reads: "How did you make this pie so delicious?" "Why it was easy enough. I tried the new way I found in my Libby's recipe booklet. Here it is - " "Pumpkin Pie: 1 ½ cups cooked and strained pumpkin, 2 eggs, ¾ cup sugar, ¼ cup molasses, ½ tablespoonful cinnamon, ½ tablespoonful ginger, 1/8 teaspoonful salt, 1 cup (1/2 can) Libby’s Evaporated Milk, with 1 cupful water. Mix pumpkin, molasses, sugar and spices together. Add the mixed milk and water, then add the eggs thoroughly beaten. Mix well and put into deep pie tins lined with pastry. Bake 45 minutes in a moderate oven. "Libby’s Evaporated Milk "For all pies and baking, for soups, coffee, tea or cocoa Libby’s milk gives an added richness and a delicious flavor. Libby’s milk is evaporate din clean, sanitary condenseries, located in the heart of the greatest dairy regions in the world. It is always pure and when open will keep sweet longer than raw milk. "Buy Libby’s milk for convenience and satisfaction. It’s the brand you can trust. "Send for a copy of Libby’s Milk Recipe Booklet. Libby, McNeill & Libby, Chicago." My research has not been exhaustive, but as far as I can tell, Libby's was the first to develop a recipe for pumpkin pie using evaporated milk. Sadly I have been unable to track down a copy of the 1912 edition of their Milk Recipes Booklet, but if anyone has one, please send a scan of the page featuring the pumpkin pie recipe! Curiously enough, the original 1912 recipe treats the evaporated milk like regular fluid milk, which was a common pumpkin pie ingredient at the time. Instead of just using the evaporated milk as-is, it calls for diluting it with water! The recipe also calls for molasses, and less cinnamon than the 1950s recipe, which also features cloves, which are missing from the 1912 version. Both versions, of course, call for using your own prepared pie crust. Nowadays Libby's recipe calls for using Nestle's Carnation brand evaporated milk - both companies are subsidiaries of ConAgra - and Libby's own canned pumpkin replaced the home-cooked pumpkin after it purchased the Dickinson canning company in 1929. Interestingly, this 1912 version (which presumably is also in Libby's milk recipe booklet) does not show up again in Libby's advertisements. Indeed, pumpkin pie is rarely mentioned at all again in Libby's ads until the 1930s - after it acquires Dickinson. And by the 1950s, the recipe wasn't even making the advertisements - Libby's wanted you to buy their canned pumpkin in order to access it - via the label. The 1950s recipe on the can persisted for decades. But in 2019, Libby's updated their pumpkin pie recipe again. This time, the evaporated milk and sugar have been switched out for sweetened condensed milk and less sugar. As many bakers know, the older recipe was very liquid, which made bringing it to the oven an exercise in balance and steady hands (although really the trick is to pull out the oven rack and then gently move the whole thing back into the oven). This newer recipe makes a thicker filling that is less prone to spillage. Still - many folks prefer the older recipe, especially at Thanksgiving, which is all about nostalgia for so many Americans. I'll admit the original Libby's is hard to beat if you're using canned pumpkin, but Lydia Maria Child's recipe also turned out lovely - just a little more labor intensive. I've even made pumpkin custard without a crust. Are you a fan of pumpkin pie? Do you have a favorite pumpkin pie recipe? Share in the comments, and Happy Thanksgiving! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

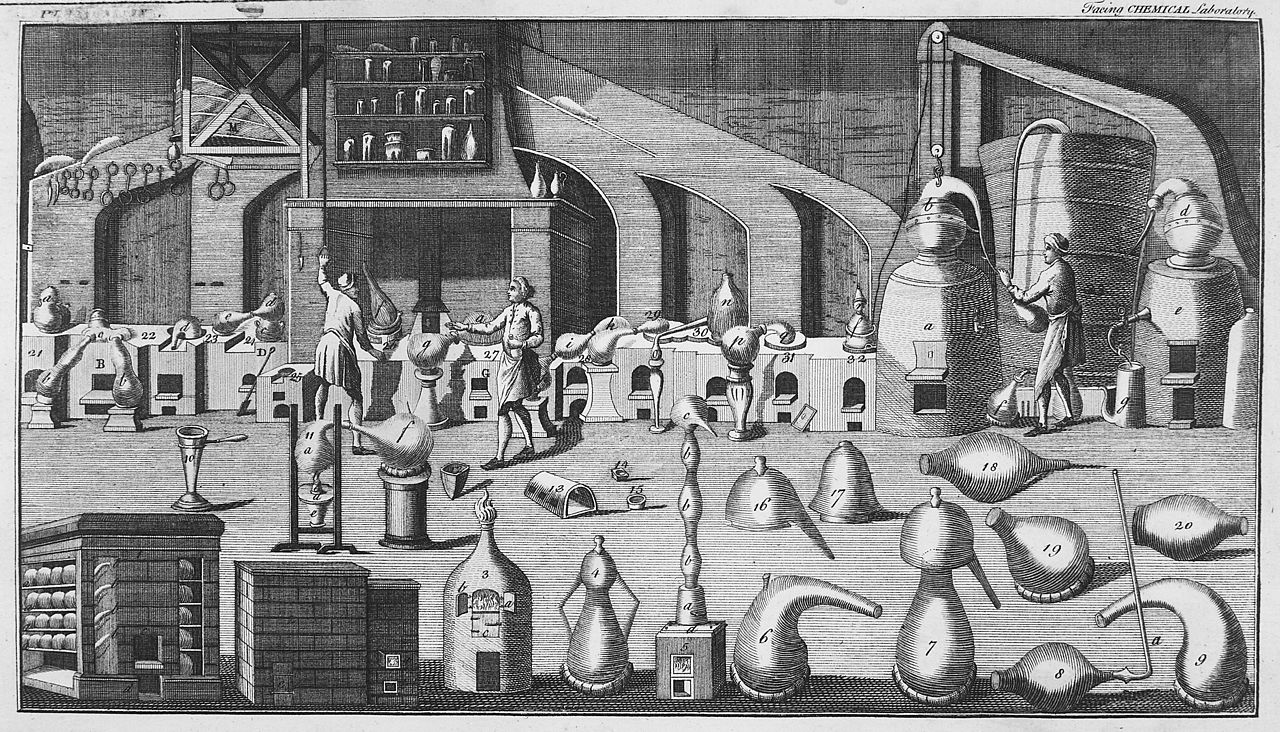

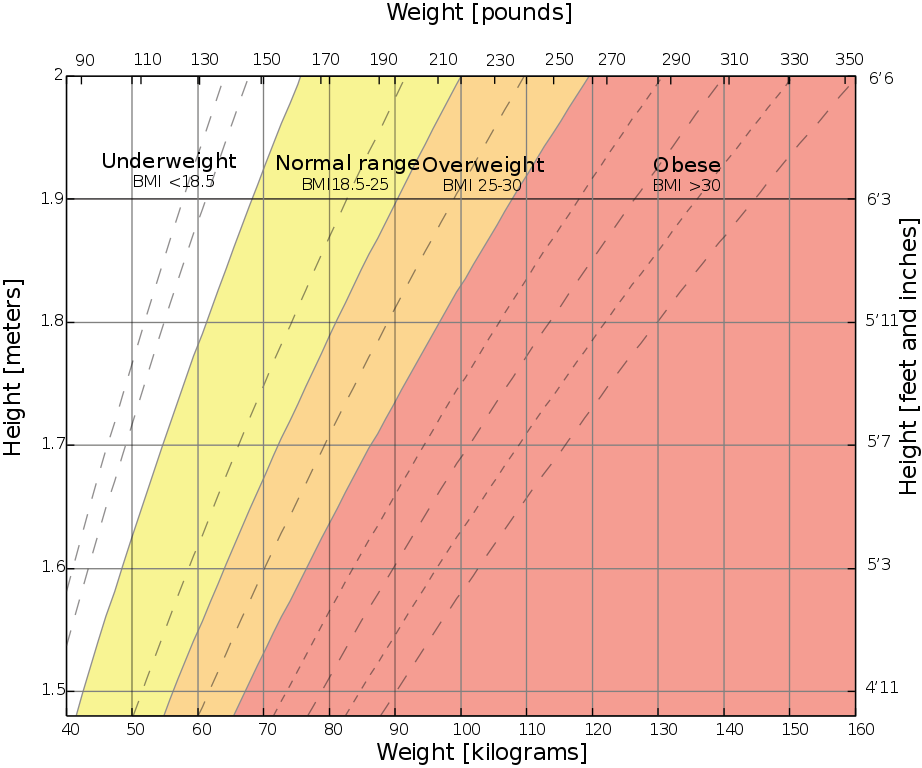

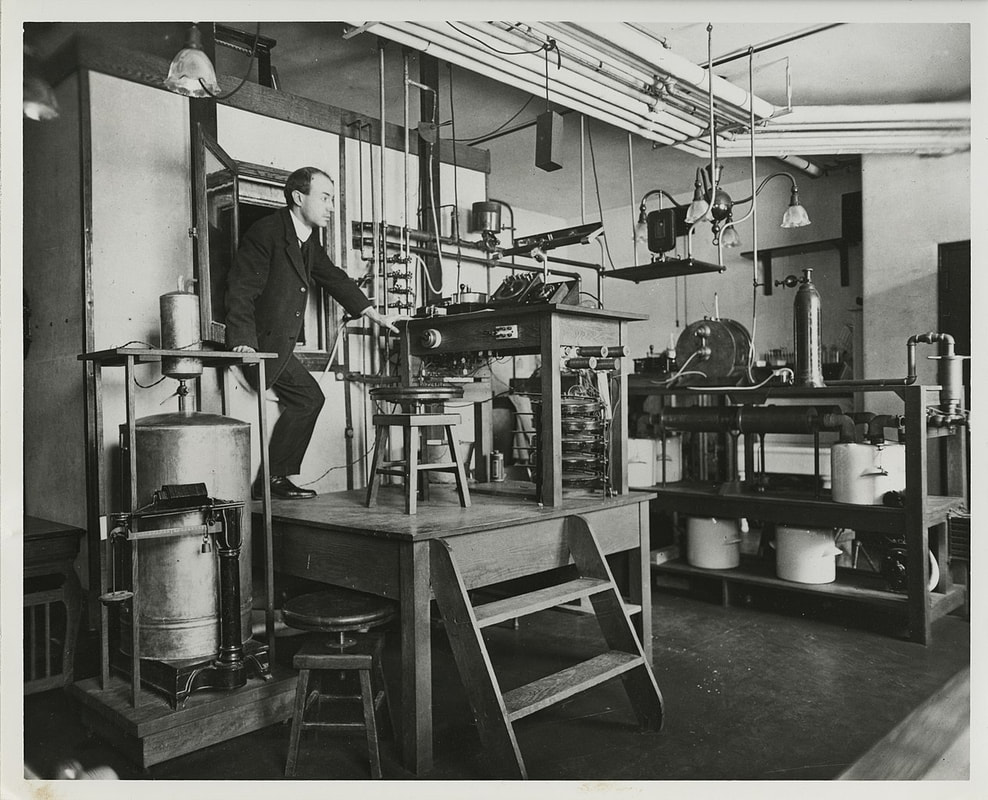

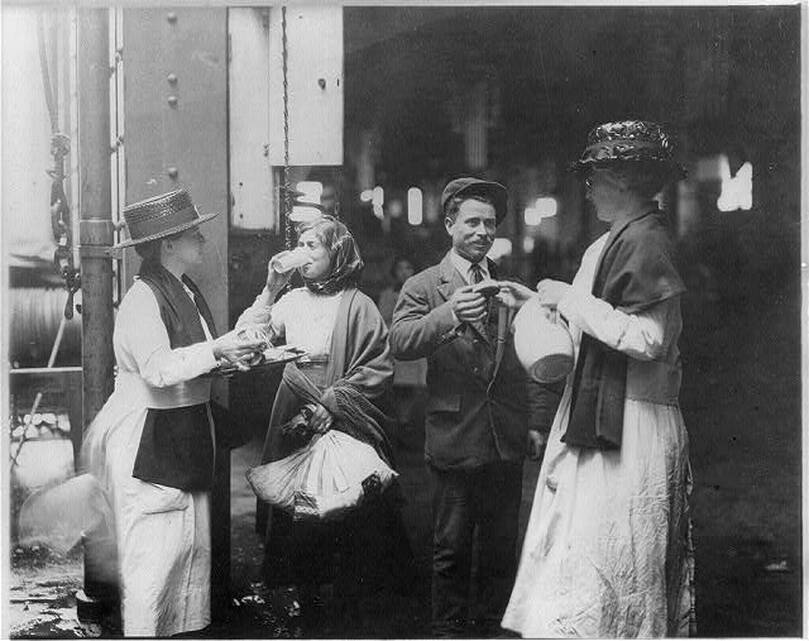

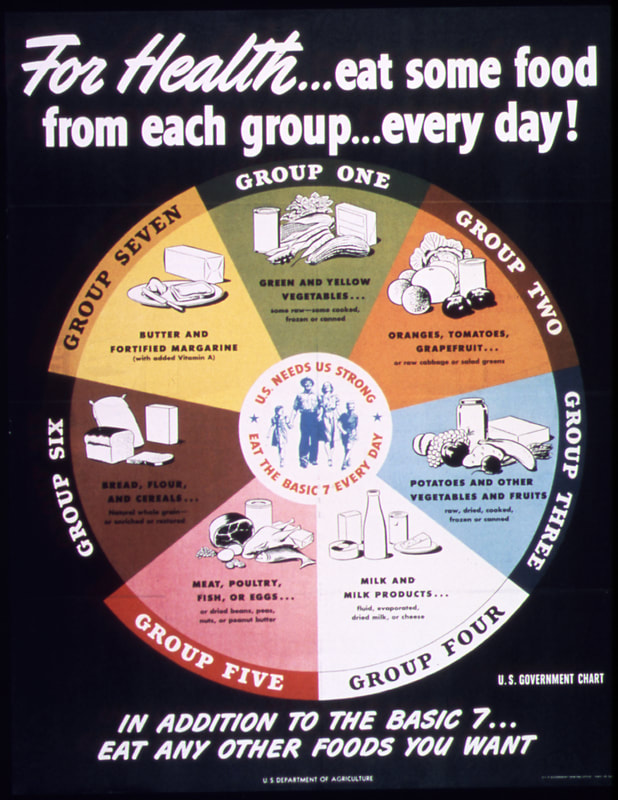

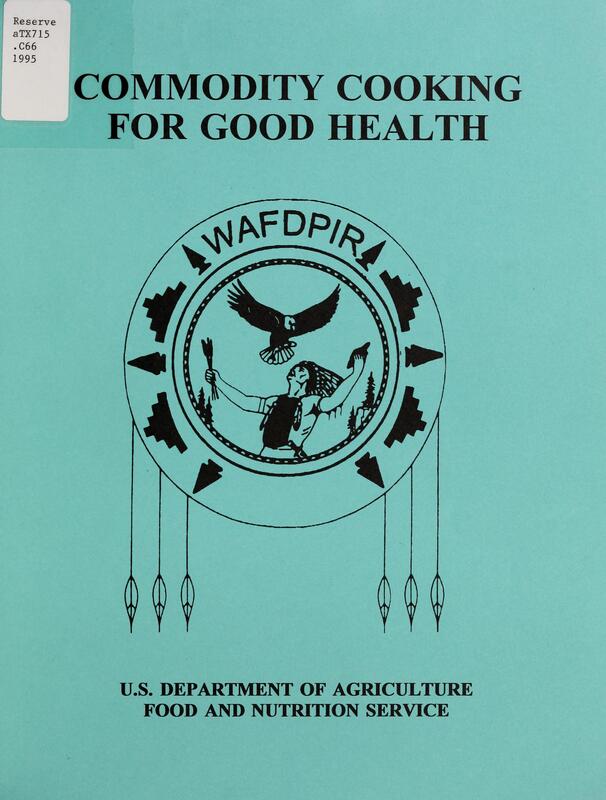

The short answer? At least in the United States? Yes. Let's look at the history and the reasons why. I post a lot of propaganda posters for World War Wednesday, and although it is implied, I don't point out often enough that they are just that - propaganda. They are designed to alter peoples' behavioral patterns using a combination of persuasion, authority, peer pressure, and unrealistic portrayals of culture and society. In the last several months of sharing propaganda posters on social media for World War Wednesday, I've gotten a couple of comments on how much they reflect an exclusively White perspective. Although White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture was the dominant culture in the United States at the time, it was certainly not the only culture. And its dominance was the result of White supremacy and racism. This is reflected in the nutritional guidelines and nutrition science research of the time. The First World War takes place during the Progressive Era under a president who re-segregated federal workplaces that had been integrated since Reconstruction. It was also a time when eugenics was in full swing, and the burgeoning field of nutrition science was using racism as justifications for everything from encouraging assimilation among immigrant groups by decrying their foodways and promoting White Anglo-Saxon Protestant foodways like "traditional" New England and British foods to encouraging "better babies" to save the "White race" from destruction. Nutrition science research with human subjects used almost exclusively adult White men of middle- and upper-middle class backgrounds - usually in college. Certain foods, like cow's milk, were promoted heavily as health food. Notions of purity and cleanliness also influenced negative attitudes about immigrants, African Americans, and rural Americans. During World War II, Progressive-Era-trained nutritionists and nutrition scientists helped usher in a stereotypically New England idea of what "American" food looked like, helping "kill" already declining regional foodways. Nutrition research, bolstered by War Department funds, helped discover and isolate multiple vitamins during this time period. It's also when the first government nutrition guidelines came out - the Basic 7. Throughout both wars, the propaganda was focused almost exclusively on White, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans. Immigrants and African Americans were the target of some campaigns for changing household habits, usually under the guise of assimilation. African Americans were also the target of agricultural propaganda during WWII. Although there was plenty of overt racism during this time period, including lynching, race massacres, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and more, most of the racism in nutrition, nutrition science, and home economics came in two distinct types - White supremacy (that is, the belief that White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values were superior to every other ethnicity, race, and culture) and unconscious bias. So let's look at some of the foundations of modern nutrition science through these lenses. Early Nutrition ScienceNutrition Science as a field is quite young, especially when compared to other sciences. The first nutrients to be isolated were fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fats were the easiest to determine, since fat is visible in animal products and separates easily in liquids like dairy products and plant extracts. The term "protein" was coined in the 1830s. Carbohydrates began to be individually named in the early 19th century, although that term was not coined until the 1860s. Almost immediately, as part of nearly any early nutrition research, was the question of what foods could be substituted "economically" for other foods to feed the poor. This period of nutrition science research coordinated with the Enlightenment and other pushes to discover, through experimentation, the mechanics of the universe. As such, it was largely limited to highly educated, White European men (although even Wikipedia notes criticism of such a Euro-centric approach). As American colleges and universities, especially those driven by the Hatch Act of 1877, expanded into more practical subjects like agriculture, food and nutrition research improved. American scientists were concerned more with practical applications, rather than searching for knowledge for knowledge's sake. They wanted to study plant and animal genetics and nutrition to apply that information on farms. And the study of human nutrition was not only to understand how humans metabolized foods, but also to apply those findings to human health and the economy. But their research was influenced by their own personal biases, conscious and unconscious. The History of Body Mass Index (BMI)Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a result of that same early 19th century time period. It was invented by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet in the 1830s and '40s specifically as a "hack" for determining obesity levels across wide swaths of population, not for individuals. Quetelet was a trained astronomist - the one field where statistical analysis was prevalent. Quetelet used statistics as a research tool, publishing in 1835 a book called Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, the English translation of which is usually called A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. In it, he discusses the use of statistics to determine averages for humanity (mainly, White European men). BMI became part of that statistical analysis. Quetelet named the index after himself - it wasn't until 1972 that researcher Ancel Keys coined the term "Body Mass Index," and as he did so he complained that it was no better or worse than any other relative weight index. Quetelet's work went on to influence several famous people, including Francis Galton, a proponent of social Darwinism and scientific racism who coined the term "eugenics," and Florence Nightingale, who met him in person. As a tool for measuring populations, BMI isn't bad. It can look at statistical height and weight data and give a general idea of the overall health of population. But when it is used as a tool to measure the health of individuals, it becomes extremely flawed and even dangerous. Quetelet had to fudge the math to make the index work, even with broad populations. And his work was based on White European males who he considered "average" and "ideal." Quetelet was not a nutrition scientist or a doctor - this "ideal" was purely subjective, not scientific. Despite numerous calls to abandon its use, the medical community continues to use BMI as a measure of individual health. Because it is a statistical tool not based on actual measures of health, BMI places people with different body types in overweight and obese categories, even if they have relatively low body fat. It can also tell thin people they are healthy, even when other measurements (activity level, nutrition, eating disorders, etc.) are signaling an unhealthy lifestyle. In addition, fatphobia in the medical community (which is also based on outdated ideas, which we'll get to) has vilified subcutaneous fat, which has less impact on overall health and can even improve lifespans. Visceral fat, or the abdominal fat that surrounds your organs, can be more damaging in excess, which is why some scientists and physicians advocate for switching to waist ratio measurements. So how is this racist? Because it was based on White European male averages, it often punishes women and people of color whose genetics do not conform to Quetelet's ideal. For instance, people with higher muscle mass can often be placed in the "overweight" or even "obese" category, simply because BMI uses an overall weight measure and assumes a percentage of it is fat. Tall people and people with broader than "ideal" builds are also not accurately measured. The History of the CalorieAlthough more and more people are moving away from measuring calories as a health indicator, for over 100 years they have reigned as the primary measure of food intake efficiency by nutritionists, doctors, and dieters alike. The calorie is a unit of heat measurement that was originally used to describe the efficiency of steam engines. When Wilbur Olin Atwater began his research into how the human body metabolizes food and produces energy, he used the calorie to measure his findings. His research subjects were the White male students at Wesleyan University, where he was professor. Atwater's research helped popularize the idea of the calorie in broader society, and it became essential learning for nutrition scientists and home economists in the burgeoning field - one of the few scientific avenues of study open to women. Atwater's research helped spur more human trials, usually "Diet Squads" of young middle- and upper-middle-class White men. At the time, many papers and even cookbooks were written about how the working poor could maximize their food budgets for effective nutrition. Socialists and working class unionists alike feared that by calculating the exact number of calories a working man needed to survive, home economists were helping keep working class wages down, by showing that people could live on little or inexpensive food. Calculating the calories of mixed-food dishes like casseroles, stews, pilafs, etc. was deemed too difficult, so "meat and three" meals were emphasized by home economists. Making "American" FoodEfforts to Americanize and assimilate immigrants went into full swing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as increasing numbers of "undesirable" immigrants from Ireland, southern Italy, Greece, the Middle East, China, Eastern Europe (especially Jews), Russia, etc. poured into American cities. Settlement workers and home economists alike tried to Americanize with varying degrees of sensitivity. Some were outright racist, adopting a eugenics mindset, believing and perpetuating racist ideas about criminology, intelligence, sanitation, and health. Others took a more tempered approach, trying to convince immigrants to give up the few things that reminded them of home - especially food. These often engaged in the not-so-subtle art of substitution. For instance, suggesting that because Italian olive oil and butter were expensive, they should be substituted with margarine. Pasta was also expensive and considered to be of dubious nutritional value - oatmeal and bread were "better." A select few realized that immigrant foodways were often nutritionally equivalent or even superior to the typical American diet. But even they often engaged in the types of advice that suggested substituting familiar ingredients with unfamiliar ones. Old ideas about digestion also influenced food advice. Pickled vegetables, spicy foods, and garlic were all incredibly suspect and scorned - all hallmarks of immigrant foodways and pushcart operators in major American cities. The "American" diet advocated by home economists was highly influenced by Anglo-Saxon and New England ideals - beef, butter, white bread, potatoes, whole cow's milk, and refined white sugar were the nutritional superstars of this cuisine. Cooking foods separately with few sauces (except white sauce) was also a hallmark - the "meat and three" that came to dominate most of the 20th century's food advice. Rooted in English foodways, it was easy for other Northern European immigrants to adopt. Although French haute cuisine was increasingly fashionable from the Gilded Age on, it was considered far out of reach of most Americans. French-style sauces used by middle- and lower-class cooks were often deemed suspect - supposedly disguising spoiled meat. Post-Civil War, Yankee New England foodways were promoted as "American" in an attempt to both define American foodways (which reflected the incredibly diverse ecosystems of the United States and its diverse populations) and to unite the country after the Civil War. Sarah Josepha Hale's promotion of Thanksgiving into a national holiday was a big part of the push to define "American" as White and Anglo-Saxon. This push to "Americanize" foodways also neatly ignores or vilifies Indigenous, Asian-American, and African American foodways. "Soul food," "Chinese," and "Mexican" are derided as unhealthy junk food. In fact, both were built on foundations of fresh, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But as people were removed from land and access to land, the they adapted foodways to reflect what was available and what White society valued - meat, dairy, refined flour, etc. Asian food in particular was adapted to suit White palates. We won't even get into the term "ethnic food" and how it implies that anything branded as such isn't "American" (e.g. White). Divorcing foodways from their originators is also hugely problematic. American food has a big cultural appropriation problem, especially when it comes to "Mexican" and "Asian" foods. As late as the mid-2000s, the USDA website had a recipe for "Oriental salad," although it has since disappeared. Instead, we get "Asian Mango Chicken Wraps," and the ingredients of mango, Napa cabbage, and peanut butter are apparently what make this dish "Asian," rather than any reflection of actual foodways from countries in Asia. Milk - The Perfect FoodCombining both nutrition research of the 19th century and also ideas about purity and sanitation, whole cow's milk was deemed by nutrition scientists and home economists to be "the perfect food" - as it contained proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all in one package. Despite issues with sanitation throughout the 19th century (milk wasn't regularly pasteurized until the 1920s), milk became a hallmark of nutrition advice throughout the Progressive Era - advice which continues to this day. Throughout the history of nutritional guidelines in the U.S., milk and dairy products have remained a mainstay. But the preponderance of advice about dairy completely ignores that wide swaths of the population are lactose intolerant, and/or did not historically consume dairy the way Europeans did. Indigenous Americans, and many people of African and Asian descent historically did not consume cow's milk and their bodies often do not process it well. This fact has been capitalized upon by both historic and modern racists, as milk as become a symbol of the alt-right. Even today, the USDA nutrition guidelines continue to recommend at least three servings of dairy per day, an amount that can cause long term health problems in communities that do not historically consume large amounts of dairy. Nutrition Guidelines HistoryBecause Anglo-centric foodways were considered uniquely "American" and also the most wholesome, this style of food persisted in government nutritional guidelines. Government-issued food recommendations and recipes began to be released during the First World War and continued during the Great Depression and World War II. These guidelines and advice generally reinforced the dominant White culture as the most desirable. Vitamins were first discovered as part of research into the causes of what would come to be understood as vitamin deficiencies. Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency), rickets (Vitamin D deficiency), beriberi (Vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency), and pellagra (Vitamin B2 or niacin deficiency) plagued people around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vitamin C was the first to be isolated in 1914. The rest followed in the 1930s and '40s. Vitamin fortification took off during World War II. The Basic 7 guidelines were first released during the war and were based on the recent vitamin research. But they also, consciously or not, reinforced white supremacy through food. Confident that they had solved the mystery of the invisible nutrients necessary for human health, American nutrition scientists turned toward reconfiguring them every which way possible. This is the history that gives us Wonder Bread and fortified breakfast cereals and milk. By divorcing vitamins from the foods in which they naturally occur (foods that were often expensive or scarce), nutrition scientists thought they could use equivalents to maintain a healthy diet. As long as people had access to vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, it didn't matter how they were delivered. Or so they thought. This policy of reducing foods to their nutrients and divorcing food from tradition, culture, and emotion dates back to the Progressive Era and continues to today, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Commodities & NutritionDivorcing food from culture is one government policy Indigenous people understand well. U.S. treaty violations and land grabs led to the reservation system, which forcibly removed Native people from their traditional homelands, divorcing them from their traditional foodways as well. Post-WWII, the government helped stabilize crop prices by purchasing commodity foods for use in a variety of programs operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the National School Lunch Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program. For most of these programs, the government purchases surplus agricultural commodities to help stabilize the market and keep prices from falling. It then distributes the foods to low-income groups as a form of food assistance. Commodity foods distributed through the FDPIR program were generally canned and highly processed - high in fat, salt, and sugar and low in nutrients. This forced reliance on commodity foods combined with generational trauma and poverty led to widespread health disparities among Indigenous groups, including diabetes and obesity. Which is why I was appalled to find this cookbook the other day. Commodity Cooking for Good Health, published by the USDA in 1995 (1995!) is a joke, but it illustrates how pervasive and long-lasting the false equivalency of vitamins and calories can be. The cookbook starts with an outline of the 1992 Food Pyramid, whose base rests on bread, pasta, cereal, and rice. It then goes to outline how many servings of each group Indigenous people should be eating, listing 2-3 servings a day for the dairy category, but then listing only nonfat dry milk, evaporated milk, and processed cheese as the dairy options. In the fruit group, it lists five different fruit juices as servings of fruit. It has a whole chapter on diabetes and weight loss as well as encouraging people to count calories. With the exception of a recipe for fry bread, one for chili, and one for Tohono O'odham corn bread, the remainder of the recipes are extremely European. Even the "Mesa Grande Baked Potatoes" are not, as one would assume from the title, a fun take on baked whole potatoes, but rather a mixture of dehydrated mashed potato flakes, dried onion soup mix, evaporated milk, and cheese. You can read the whole cookbook for yourself, but the fact of the matter is that the USDA is largely responsible for poor health on reservations, not only because it provides the unhealthy commodity foods, but also because it was founded in 1862, the height of the Indian Wars, during attempts by the federal government at genocide and successful land grabs. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the Department of the Interior was largely responsible for the reservation system, the land grant agricultural college system started by the Hatch Act was literally built on the sale of stolen land. In addition, the USDA has a long history of dispossessing Black farmers, an issue that continues to this day through the denial of farm loans. Thanks to redlining, people of color, especially Black people, often live in segregated school districts whose property taxes are inadequate to cover expenses. Many children who attend these schools are low-income, and rely on free or reduced lunch delivered through the National School Lunch Program, which has been used for decades to prop up commodity agriculture. Although school lunch nutrition efforts have improved in recent years, many hot lunches still rely on surplus commodities and provide inadequate nutrition. Issues That PersistEven today, the federal nutrition guidelines, administered by the USDA, emphasize "meat and three" style meals accompanied by dairy. And while the recipe section is diversifying, it is still all-too-often full of Americanized versions of "ethnic" dishes. Many of the dishes are still very meat- and dairy-centric, and short on fresh fruits and vegetables. Some recipes, like this one, seem straight out of 1956. The idea that traditional ingredients should be replaced with "healthy" variations, for instance always replacing white rice with brown rice or, more recently cauliflower rice, continues. Many nutritionists also push the Mediterranean Diet as the healthiest in the world, when in fact it is very similar to other traditional diets around the world where people have access to plenty of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, etc. Even the name - the "Mediterranean Diet," implies the diets of everyone living along the Mediterranean. So why does "Mediterranean" always mean Italian and Greek food, and never Persian, Egyptian, or Tunisian food? (Hint: the answer is racism). Old ideas about nutrition, including emphasis on low-fat foods, "meat and three" style recipes, replacement ingredients (usually poor cauliflower), and artificial sweeteners for diabetics, seem hard to shake for many people. Doctors receive very little training in nutrition and hospital food is horrific, as I saw when my father-in-law was hospitalized for several weeks in 2019. As a diabetic with problems swallowing, pancakes with sugar-free syrup, sugar-free gelatin and pudding, and not much else were their solution to his needs. The modern field of nutritionists is also overwhelmingly White, and racism persists, even towards trained nutritionists of color, much less communities of color struggling with health issues caused by generational trauma, food deserts, poverty, and overwork. Our modern food system has huge structural issues that continue to today. Why is the USDA, which is in charge of promoting agriculture at home and abroad, in charge of federal nutrition programs? Commodity food programs turn vulnerable people into handy props for industrial agriculture and the economy, rather than actually helping vulnerable people. Federal crop subsidies, insurance, and rules assigns way more value to commodity crops than fruits and vegetables. This government support also makes it easy and cheap for food processors to create ultra-processed, shelf-stable, calorie-dense foods for very little money - often for less than the crops cost to produce. This makes it far cheaper for people to eat ultra-processed foods than fresh fruits and vegetables. The federal government also gives money to agriculture promotion organizations that use federal funds to influence American consumers through advertising (remember the "Got Milk?" or "The Incredible, Edible Egg" marketing? That was your taxpayer dollars at work), regardless of whether or not the foods are actually good for Americans. Nutrition science as a field has a serious study replication problem, and an even more serious communications problem. Although scientists themselves usually do not make outrageous claims about their findings, the fact that food is such an essential part of everyday life, and the fact that so many Americans are unsure of what is "healthy" and what isn't, means that the media often capitalizes on new studies to make over-simplified announcements to drive viewership. Key TakeawaysNutrition science IS a science, and new discoveries are being made everyday. But the field as a whole needs to recognize and address the flawed scientific studies and methods of the past, including their racism - conscious or unconscious. Nutrition scientists are expanding their research into the many variables that challenge the research of the Progressive Era, including gut health, environmental factors, and even genetics. But human research is expensive, and test subjects rarely diverse. Nutrition science has a particularly bad study replication problem. If the government wants to get serious about nutrition, it needs to invest in new research with diverse subjects beyond the flawed one-size-fits-all rhetoric. The field of nutrition - including scientists, medical professionals, public health officials, and dieticians - need to get serious about addressing racism in the field. Both their own personal biases, as well as broader institutional and cultural ones. Anyone who is promoting "healthy" foods needs to think long and hard about who their audience is, how they're communicating, and what foods they're branding as "unhealthy" and why. We also need to address the systemic issues in our food system, including agriculture, food processing, subsidies, and more. In particular, the government agencies in charge of nutrition advice and food assistance need to think long and hard about the role of the federal government in promoting human health and what the priorities REALLY are - human health? or the economy? There is no "one size fits all" recommendation for human health. Ever. Especially not when it comes to food. Because nutrition guidelines have problems not just with racism, but also with ableism and economics. Not everyone can digest "healthy" foods, either due to medical issues or medication. Not everyone can get adequate exercise, due to physical, mental, or even economic issues. And I would argue that most Americans are not able to afford the quality and quantity of food they need to be "healthy" by government standards. And that's wrong. Like with human health, there are no easy solutions to these problems. But recognizing that there is a problem is the first step on the path to fixing them. Further ReadingMany of these were cited in the text of the article above, but they are organized here for clarity. I have organized them based on the topics listed above. (note: any books listed below are linked as part of the Amazon Affiliate program - any purchases made from those links will help support The Food Historian's free public articles like this one). EARLY NUTRITION SCIENCE

A HISTORY OF BODY MASS INDEX (BMI)

THE HISTORY OF THE CALORIE

MAKING "AMERICAN" FOOD

MILK - THE PERFECT FOOD

NUTRITION GUIDELINES HISTORY

COMMODITIES AND NUTRITION

ISSUES THAT PERSIST

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

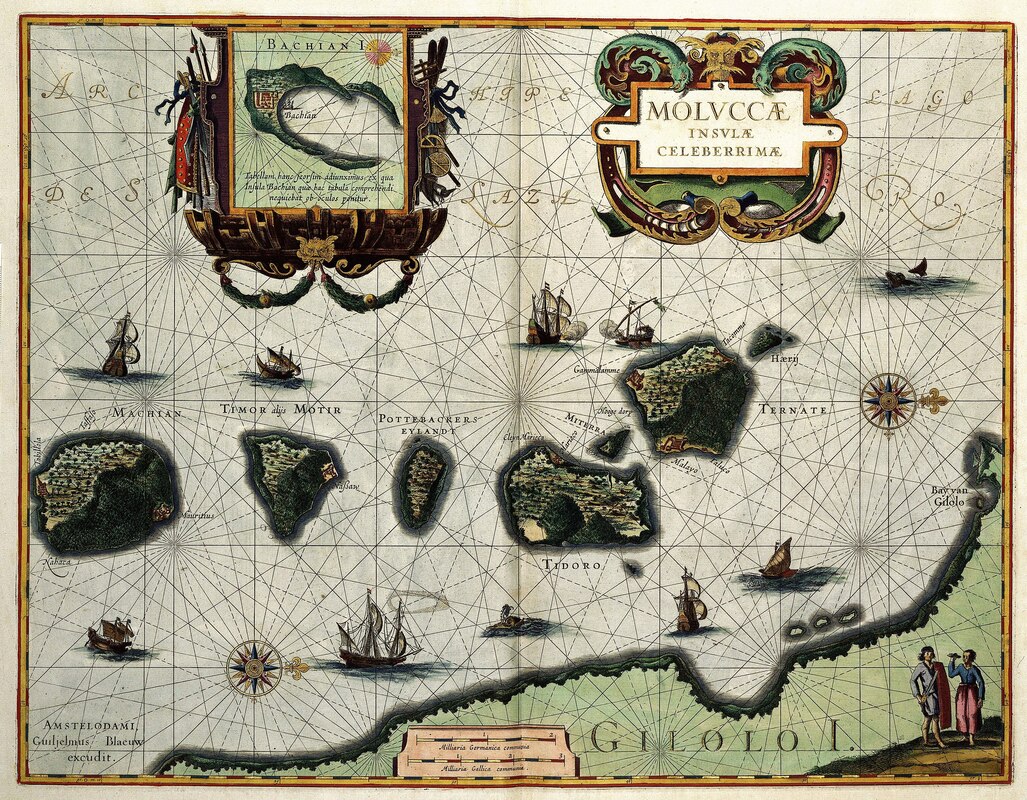

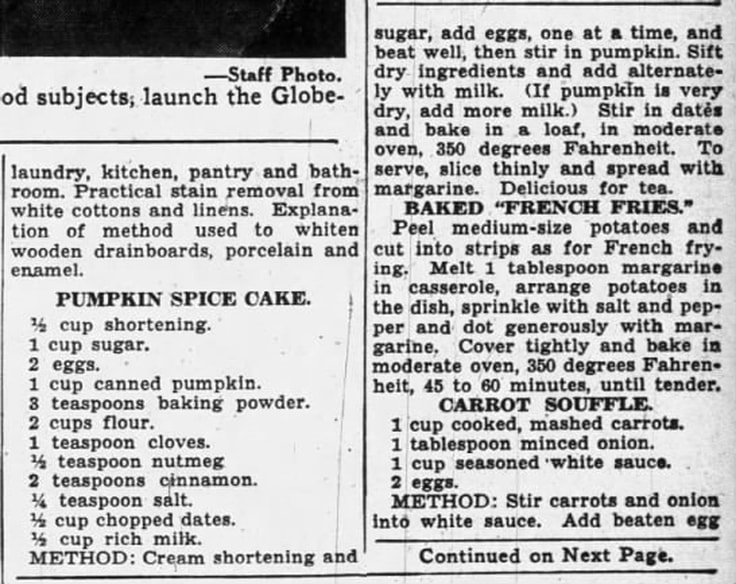

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Pop culture these days seems dominated by arguments over whether or not the pumpkin spice latte (or PSL) is "basic" or not, whether or not enjoying pumpkin spice flavored things can only happen during the few short months of autumn, and whether "fall creep" plays a role in "ruining" some people's summers. But have you ever wondered WHY we eat pumpkin pie spice - and other sweet spices - mostly in the fall? Pumpkin pie spice is a mixture of sweet spices - cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, and either cloves and/or allspice. With the exception of allspice, all of these spices are native to Southeast Asia, especially the so-called "Spice Islands," more commonly known as the Maluku Islands (or Molucca Islands) near Indonesia, where nutmeg trees (which also provide mace) and clove trees originated. Cinnamon is native to Sri Lanka, and ginger is native to Maritime Southeast Asia. Allspice is also a plant of the tropics, native to the Caribbean and Central Mexico. So why do we so strongly associate these flavors with cold fall and winter months in the Northern hemisphere? A Brief History of the Spice Trade This map of the Moluccas Islands was published in 1630 by Willem Jansz. Blaeu (1571-1638). This map clearly shows that very little was known at the time about the Indonesian Archipel. The map shows the islands close together though in reality they are often thousands of miles apart. From the collections of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek. As with many things, it all has to do with money. Prior to the 16th century, all of these spices were available in Europe traveling via trade routes across Asia. Chinese and Arab traders traveled overland via the Silk Road or on ships from the Red Sea across the Indian Ocean. Cinnamon, ginger, and black pepper (native to the Malabar coast of India) were all known in Europe as far back as Ancient Rome. For centuries, Venice controlled much of the flow of spices into Europe, and the wealth gained by the spice trade may have helped spark the Renaissance. But when the Ottoman Empire wrested control of the spice trade from Europeans in 1453, things changed. European nations, spurred by improvements in naval technology, started to search for their own routes to control the lucrative spice trade. Indeed, most of the European "explorers" who ended up in the Americas were searching for a shortcut to Asia and a way to bypass the control of the Muslim Ottoman Empire and cut out the middleman altogether, ensuring massive profits. Instead of dealing with existing trade relationships, as Asian and Arab traders had for centuries, Europeans simply took what they wanted by force. The Dutch were particularly violent as they tried to take control of the Spice Islands through genocide and enslavement. Even after the plants that produced these valuable spices were successfully propagated outside their native habitats, the plantations which grew them commercially were often owned by foreign Europeans and also used enslaved labor to produce the spices more cheaply than ever. Like sugar and chocolate, the plantation economy allowed spices to be produced in massive quantities quite cheaply. The flavors that were once the purview only of wealth European aristocrats were, by the end of the 18th century, much more widely affordable by ordinary people. By the middle of the 19th century, ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, mace, and cloves (along with sugar and cocoa) were positively common. Which is why foods like gingerbread cake, spice cake, and spiced pumpkin and apple pies became such indelible parts of American food history. But why the association with fall? In European cuisine, the most expensive foods were served around special feast days, like Christmas and Twelfth Night. Fruit cakes were rich in spices, spices flavored custards and puddings, and cookies flavored with ginger, cinnamon, mace, nutmeg, and cloves were all staples of the winter holidays. As spices became less expensive over time, they were used in other applications, but their association with the holidays - and cold weather - continued. In the United States, Americans flavored the prolific native squash with the now-familiar mixture of spices in a smooth custard pie. Pumpkin pie was born. Creating "Pumpkin Pie Spice"The name "pumpkin pie spice" refers to the mix of spices used to flavor pumpkin pies - among other things. Sadly, the mix itself contains no actual pumpkin, which is quite confusing when it is used as a flavoring agent sans pumpkin. Developed to flavor the smooth squash custards in a flaky crust we've all come to associate with Thanksgiving, the mixture of sweet, exotic spices was extremely popular. But as the 19th century turned to the 20th, the idea of hand grinding whole spices in a mortar and pestle was not only time-consuming, it threatened the use of spices altogether. Spice and extract companies like McCormick had been around since the late 19th century, but the 20th century brought a whole host of other companies to the scene, especially post WWII. The spice mix itself was commercialized first during the early 20th century, as spice and flavorings companies brainstormed ways to make baking easier and more economical for customers. Thompson & Taylor spice company was the first to create "ready-mixed pumpkin pie spice." The above advertisement, first published in 1933, features a woman asking an older woman with glasses "Mother - Why is it your pumpkin pies are never failures?" The older woman, who is spooning something into a pie crust, answers, "T&T Pumpkin Pie Spice my dear, makes them perfect every time." The advertisement goes on to read, "Home-made pumpkin pie, perfect in flavor, color and aroma, demands the use of nine different spices. The spices must be exactly proportioned, perfectly blended, and, above all, absolutely fresh. For reasons of economy, most housewives are right in hesitating to buy nine spices just for pumpkin pie. But here is news! Now, for the fist time, you can get the necessary nine spices, ready-mixed for instant use, in one 10c package of T&T Pumpkin Pie Spice - enough for 12 pies." Of course, they don't want to tell you what those nine spices are! But likely it was a mixture of cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, allspice, and cloves, and perhaps also mace, cardamom, star anise, and black pepper. Two years later, McCormick advertised their own "Pumpkin Pie & Ginger Bread Spice," a blend of "ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and other spices." I love that it is advertised as good for both pumpkin pie and gingerbread. Although we often associate gingerbread with Christmas, it was also often served at Halloween and throughout the colder months. As canned pumpkin grew in popularity in the 20th century, other pumpkin desserts were also developed to use the same spice profile, including pumpkin spice cake. Here's the recipe as written in the St. Louis Dispatch. Feel free to substitute shortening (and the margarine!) for butter. Pumpkin Spice Cake 1/2 cup shortening 1 cup sugar 2 eggs 1 cup canned pumpkin 3 teaspoons baking powder 2 cups flour 1 teaspoon cloves 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg 2 teaspoons cinnamon 1/4 teaspoon salt 1/2 cup chopped dates 1/2 cup rich milk METHOD: Cream shortening and sugar, add eggs, one at a time, and beat well, then stir in pumpkin. Sift dry ingredients and add alternately with milk. (If pumpkin is very dry, add more milk.) Stir in dates and bake in a loaf, in a moderate oven, 350 degrees Fahrenheit. To serve, slice thinly and spread with margarine. Delicious for tea. Spiced pumpkin foods were largely relegated to desserts for most of the 20th century - pumpkin bars, cakes, muffins, and cookies were all popular, especially after the Second World War. But we weren't at peak pumpkin spice saturation just yet. Enter, the Pumpkin Spice Latte. The Pumpkin Spice Latte and BeyondFounded in 1971 near Pike Place Market in Seattle, Washington, Starbucks originally started as a whole bean coffee company. But the specialty coffee business caught on in the dot com boom of the 1990s and franchises spread all over the country. In the 1980s, Starbucks had developed the popular holiday eggnog latte. The addition of a peppermint mocha in the early 2000s piqued corporate interest in specialty holiday drinks available for a limited time. They trialed a variety of drinks with focus groups, and the pumpkin spice latte was the surprise favorite. Released in 2003, it became a national phenomenon that only grew with time. Starbucks was not the first to develop a pumpkin spice flavored latte, but they certainly popularized it. Nowadays September and October bring the onset of just about everything pumpkin spice flavored, regardless of the weather conditions where you live. And that's the weird thing about pumpkin spice - today it is totally divorced from its geography and history. Born in the tropics, the product of genocide, enslavement, and greed, and associated for centuries with wealth and holidays, today it represents shorthand for a near-fictional concept of autumn that most Americans don't experience. Even in stereotypical New England, where pumpkin pie spice was arguably born, climate change is making autumn shorter and warmer. I'm all for letting people love what they love, and PSL and pumpkin spice are no different. I love a good spiced pumpkin dessert, don't get me wrong. But for all the fuss about pumpkin spice, I'm an apple cider girl myself. Just don't tell Starbucks or the people who seem to think everything from breakfast cereals to hand soap should be flavored with pumpkin spice. What do you think? Are you a fan of pumpkin spice? Tell me how you really feel in the comments! And if you want to learn more about the history of pumpkin pie, check out my talk "As American As Pumpkin Pie: From Colonial New England to PSL" - available on YouTube. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

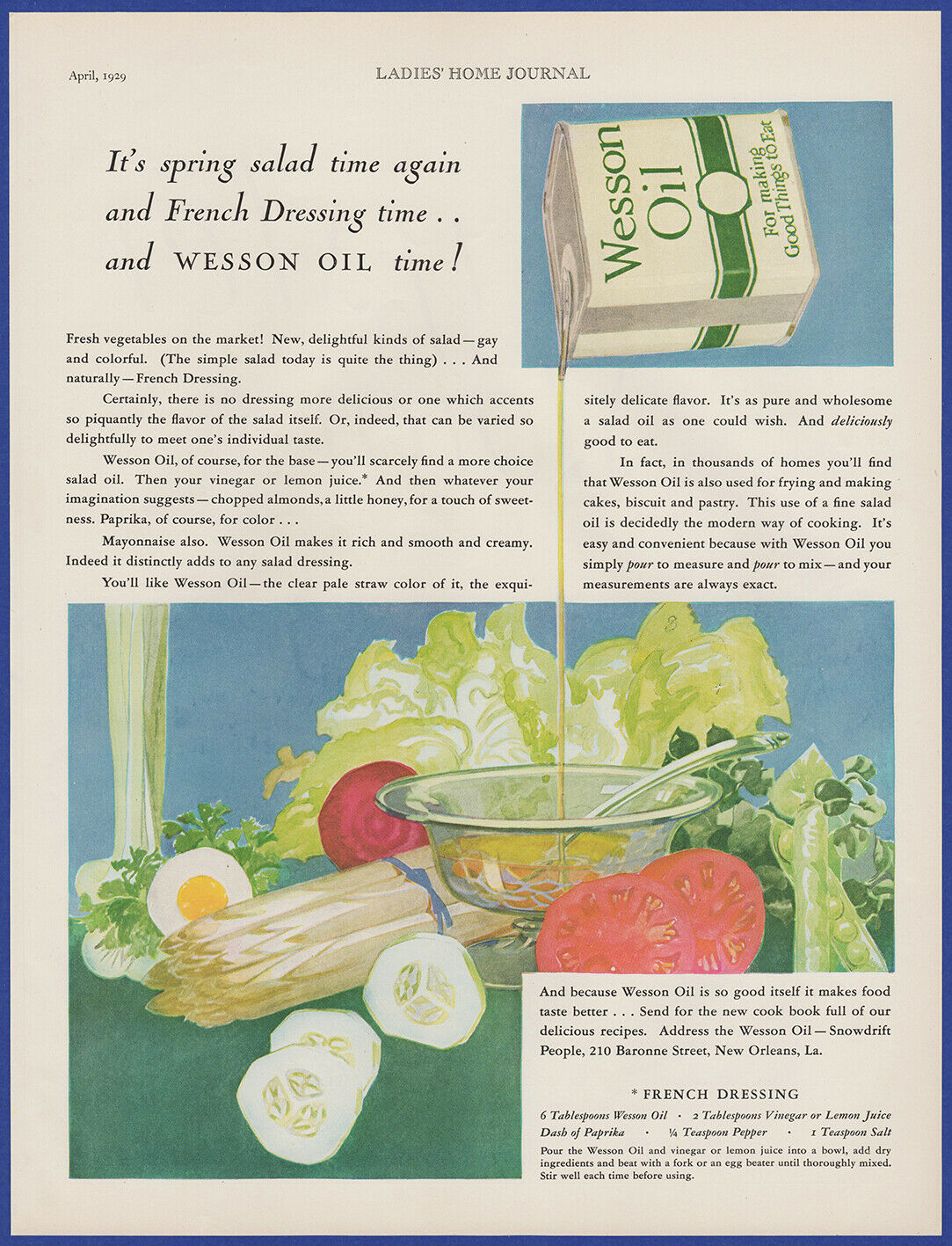

The Food and Drug Administration recently announced that it would be de-regulating French Dressing. And while people have certainly questioned why we A) regulated French Dressing in the first place and B) are bothering to de-regulate it now, much of the real story behind this de-regulation is being lost, and it's intimately tied to the history of French Dressing.

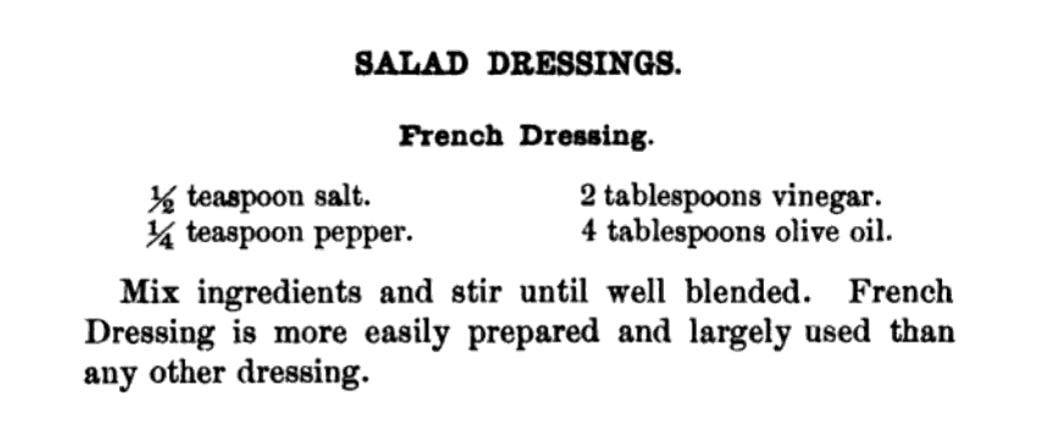

A lot of people like to claim that French Dressing is not actually French. And if you're defining French Dressing as the tangy, gloppy, red stuff pretty much no one makes from scratch anymore, you'd be right. But the devil is in the details, and even the New York Times has missed this little bit of nuance. This Times article, published before the final de-regulation went into place, notes, "The lengthy and legalistic regulations for French dressing require that it contain vegetable oil and an acid, like vinegar or lemon or lime juice. It also lists other ingredients that are acceptable but not required, such as salt, spices and tomato paste." (emphasis mine) What's that? The original definition of French Dressing, according to the FDA, was essentially a vinaigrette? What could be more French than that? In fact, that is, indeed, how "French dressing" was defined for decades. Look at any cookbook published before 1960 and nearly every reference to "French dressing" will mean vinaigrette. Many a vintage food enthusiast has been tripped up by this confusion, but it's our use of the term that has changed, not the dressing. Take, for instance, our old friend Fannie Farmer. In her 1896 Boston Cooking School Cookbook (the first and original Fannie Farmer Cookbook), the section on Salad Dressings begins with French Dressing, which calls for simply oil, vinegar, salt, and pepper.

She's not the only one. I've found references in hundreds of cookbooks up until the 1950s and '60s and even a few in the 1970s where "French dressing" continued to mean vinaigrette. You can usually tell by the recipe - composed salads of vegetables are the most common. If a recipe for "French dressing" is not included, and no brand name is mentioned, it's almost certainly a vinaigrette. So what happened?

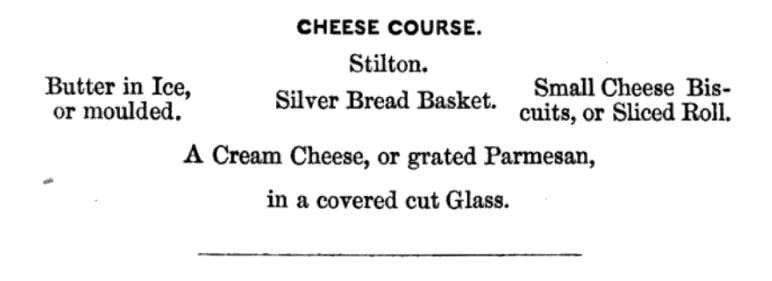

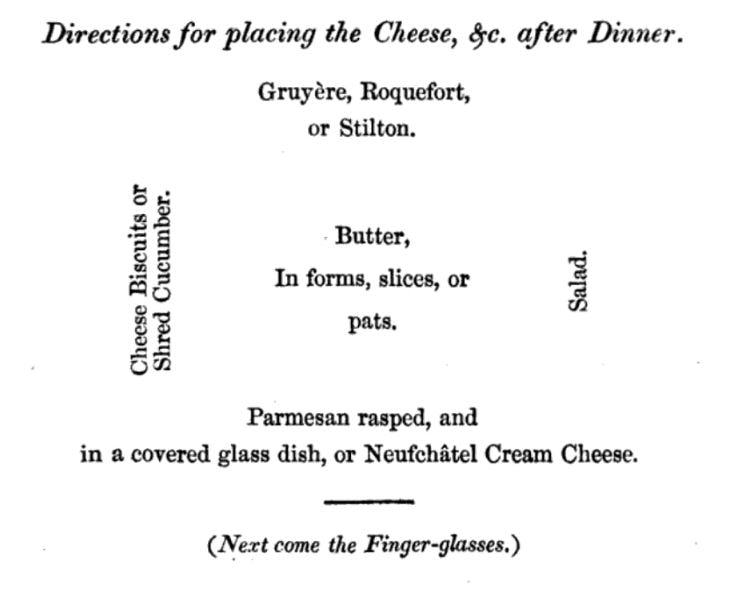

I've managed to track down the original 1950 FDA Standard of Identity for mayonnaise, French dressing, and salad dressing. In it, the three condiments are considered together and are the only dressings identified, likely because few if any other dressings were being commercially produced. Although the term "salad dressing" has been extremely confusing to many modern journalists, it is clearly noted in the 1950 standard of identity of being a semi-solid dressing with a cooked component - in short, boiled dressing. The closest most Americans get today is "Miracle Whip," which is, in fact, a combination of mayonnaise and boiled dressing. Generic brands are often called just "salad dressing" because it was often used to bind together salads like chicken, egg, crab, and ham salad, and also often used with coleslaw. So it makes perfect sense that "French dressing" would be the designated term for poured dressings designed to be eaten with cold lettuce and vegetables - i.e. what we consider salad today. People have wondered why we needed to regulate salad dressings, but there is one very important distinction in the 1950 rule - it prohibits the use of mineral oil in all three. Mineral oil, which is a non-digestible petroleum product (i.e. it has a laxative effect), and which is colorless and odorless, was a popular substitute for vegetable oil during World War II by dieters in the mid-20th century. I collect vintage diet cookbooks and it shows up frequently in early 20th century ones, especially as a substitute for salad dressings. Mineral oil is also extremely cheap when compared with vegetable oils, and it would be easy for unscrupulous food manufacturers to use it to replace the edible stuff, so the FDA was right to ensure that it did not end up in peoples' food. Mineral oil is sometimes still used today as an over-the-counter laxative, but can have serious health complications if aspirated. There were several subsequent addenda to the standard of identity, but most were about the inclusion of artificial ingredients or thickeners, with no mention of any ingredients that might change the flavor or context of what was essentially a regulation for vinaigrette until 1974, when the discussion centered around the use of artificial colors instead of paprika to change the color of the dressing. The FDA ruled that "French dressing may contain any safe and suitable color additives that will impart the color traditionally expected." So here we see that by the 1970s, the standard of identity hadn't actually changed much, but the terminology had. "French dressing" went from the name of any vinaigrette, to a specific style of salad dressing containing paprika (and/or tomato). When people started adding paprika is unclear, but it was probably sometime around the turn of the 20th century, when home economists began to put more and more emphasis on presentation and color. A lively reddish orange dressing was probably preferable to a nearly-clear one. In 2000, the LA Times made an admirable effort to track the early 20th century chronology of the orange recipes. By the 1920s, leafy and fruit salads began to overtake the heavier mayonnaise and boiled dressing combinations of meat and nuts. As the willowy figure of the Gibson Girl gave way to the boyish silhouette of the flapper, women were increasingly concerned about their weight, and salads were seen as an elegant solution.

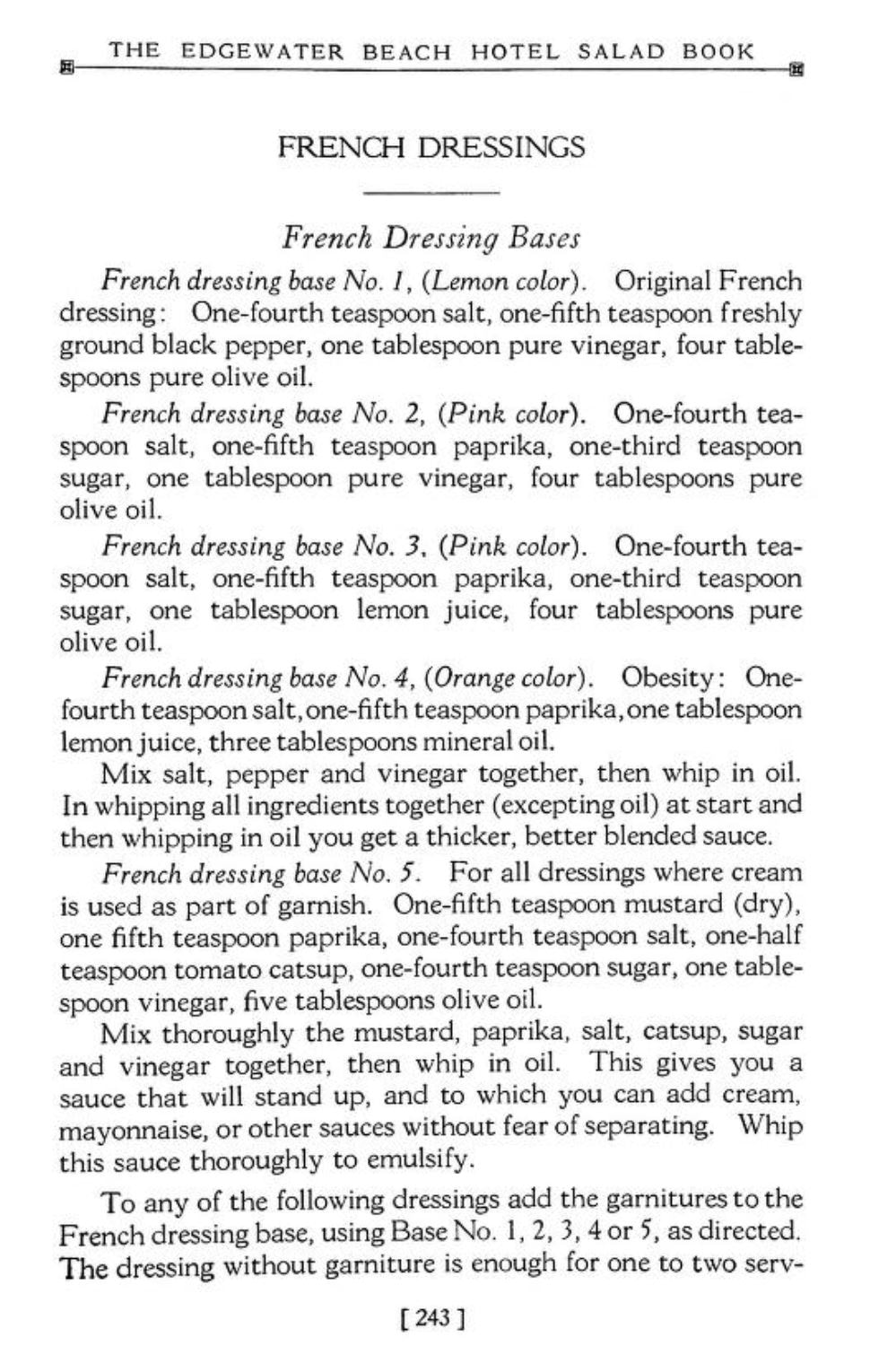

The recipes pictured above are from The Edgewater Beach Hotel Salad Book, published in 1928 (Patreon patrons already got a preview of this cookbook earlier in the week!). The Edgewater Beach Hotel was a fashionable resort on the Chicago waterfront which became known for its catering and restaurant, and in particular its elegant salads. You'll note that several French Dressing recipes are outlined (they are also introduced first in the book), and are organized by color. "No. 4 (Orange Color)" has the note "obesity" not because it would make you fat - quite the opposite - its use of mineral oil was designed for people on diets. Although the fifth recipe does not note a color, it does contain both paprika and tomato "catsup," and all but the original and "obesity" recipes contain sugar. An increase in the consumption of sweets in the early 20th century is often attributed to the Temperance movement and later Prohibition.

By the 1950s, recipes for "French Dressing" that doctored up the original vinaigrette with paprika, chili sauce, tomato ketchup, and even tomato soup abounded. My 1956 edition of The Joy Of Cooking has over three pages of variations on French Dressing. Hilariously, it also includes a "Vinaigrette Dressing or Sauce," which is essentially the oil and vinegar mixture, but with additions of finely chopped pimento, cucumber pickle, green pepper, parsley, and chives or onion, to be served either cold or hot. All the other vinaigrettes have the moniker "French dressing." A Google Books search reveals an undated but aptly titled "Random Recipes," which seems to date from approximately mid-century, and which includes a recipe for Tomato French Dressing calling for the use of Campbell's tomato soup, and "Florida 'French Dressing'," containing minute amounts of paprika, but generous citrus juices and a hint of sugar. So maybe people were making their own sweetly orange French dressing at home after all?

There is some debate as to who actually "invented" the orange stuff, but while Teresa Marzetti may have helped popularize it, the general consensus is the Milani brand, which started selling its orange take in 1938 (or the 1920s, depending who you ask - I haven't found a definitive answer one way or the other), was the first to commercially produce it. Confusingly, the official Milani name for their dressing is "1890 French Dressing." The internet has revealed no clues as to whether or not the recipe actually dates back that far, but a 1947 New York Times article claims "On the shelves at Gimbels you'll find 1890 French dressing, manufactured by Louis Milani Foods. It is made, the company says, according to a recipe that originated in Paris at that time and was brought to this country after the fall of France. This slightly sweet preparation, which contains a generous amount of tomatoes, costs 29 cents for eight ounces." This seems like a marketing ploy rather than the truth, but who knows for sure?

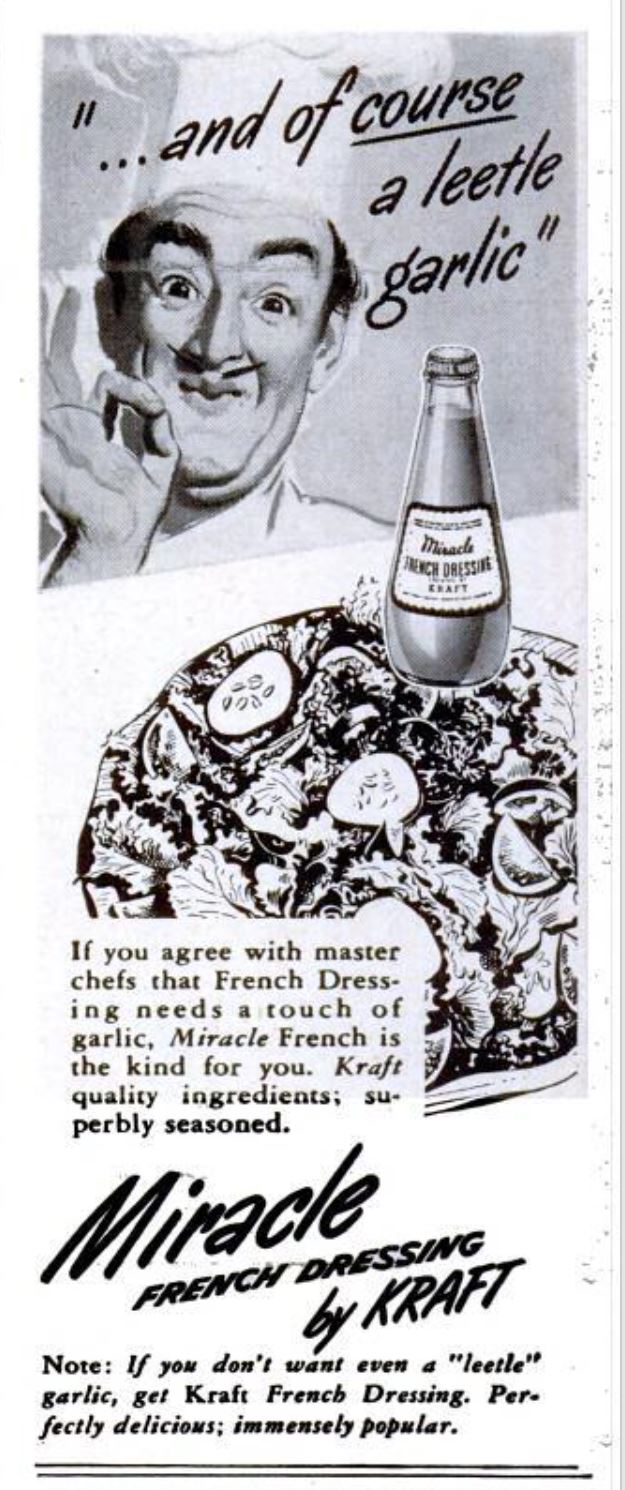

In 1925, the Kraft Cheese Company did sign a contract with the Milani Company to become their exclusive distributor. At least, that's what a snippet view of 1928 New York Stock Exchange listing statements tells me. As early as 1931 Kraft was manufacturing French Dressing under their name, and by the 1940s it had also used the Miracle Whip brand name to create Miracle French Dressing - which had just a "leetle" hint of garlic.

One snippet reference in the 1934 edition of "The Glass Packer" notes, "Differing from Kraft French Dressing, Miracle French is a thin dressing in which the oil and vinegar separate in the bottle, and which must be shaken immediately before using." Miracle French was contrasted often in advertising with classic Kraft French as being zestier, which may have led to the development in the 1960s of Kraft's Catalina dressing, a thinner, spicier, orange-er French dressing.

In fact, as featured in this undated magazine advertisement, Kraft at one point had several varieties of French Dressing including actual vinaigrettes like "Oil & Vinegar," and "Kraft Italian" alongside Catalina, Miracle French, Casino, Creamy Kraft French, and Low Calorie dressing, which also looks like French dressing. What you may notice is that the "Creamy Kraft French" looks suspiciously like most of the gloppy orange stuff you see on shelves today, and which generally doesn't resemble a thin, runny, paprika/tomato-red dressing that dominates the rest of this lineup.

"Spicy" Catalina dressing was likely introduced sometime around 1960 (although the name wasn't trademarked until 1962). Kraft Casino dressing (even more garlicky) was trademarked for both cheese and French dressing in 1951, but by the 1970s appears to have left the lineup. Here are a few fun advertisements that compare some of the Kraft French dressings:

Of course by the 1950s other dressing manufacturers besides Kraft were getting in on the salad dressing game, including modern holdouts like:

Although many people in the United States grew up eating the creamy orange version of French Dressing, it's mostly vilified today (aside from a few enthusiasts). Which is too bad. As a dyed-in-the-wool ranch lover (hello, Midwestern upbringing - have you tried ranch on pizza?), I try not to judge peoples' food preferences. And I have to admit that while I've come to enjoy homemade Thousand Island dressing, I can't say that I've ever actually had the orange French! Of any stripe, creamy, spicy, or otherwise. I'm much more likely to use homemade vinaigrette from everything from lentil, bean, and potato salads to leafy greens. So to that end, let's close with a little poll. Now that you know the history of French Dressing, do you have a favorite? Tell us why in the comments!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

There's this weird trend in modern America where we love to mock the foods of the 1950s (and, to a lesser extent, the 1960s and '70s). Everyone from James Lileks (here and here) to Buzzfeed-style listicles to internet memelords have weighed in on how terrible food was in the 1950s. But was it? Was it really? Or are we just expressing bias (conscious or not) about foods we haven't tried and don't understand? I have seen this meme all over my social feeds lately. Including, regrettably, in some food history and food studies groups. Some clever memer stole an image from Midcentury Menu (which is a delightful blog, please check out Ruth's work) and added their own commentary. The author of the meme is unclear, but it appears to have been posted about a week ago. Whenever I challenge the idea that maybe 1950s foods aren't nearly as bad as we think they are, I often get accused of engaging in nostalgia (spoiler alert, I was born in the 1980s) or romanticizing the past, usually accompanied by an assertion that these foods are "objectively" bad. But I can't help but thinking of how our concepts of disgust are much more a product of the society and time period we were brought up in, than anything resembling objectivity. The New York Times Magazine just published an article about the science of disgust earlier this week, but what I find interesting about the article is how many of the examples centered on food, and yet how little food is actually discussed. Indeed, almost all of the science of disgust seems focused entirely on evolutionary factors, such as protecting us from spoiled foods, from acquiring diseases from bodily fluids and corpses, or from weakening our gene pool through incest. Very few people outside of the food world discuss the cultural reasons behind disgust that have nothing to do with biology and everything to do with cultural, racial, religious, and ethnic factors. Earlier this year The New Yorker published a piece by Jiayang Fan on the controversial Disgusting Food Museum in Malmo, Sweden. The museum "collects" foods from around the world that its founders deem disgusting, with much controversy. Although the museum includes European foods like stinky fermented fish and salty licorice, it also includes many foods from non-Western societies. Many argue it reinforces cultural prejudices. Fan does not make specific value judgements about the museum itself, but does share her personal experiences as a Chinese person in the United States. I found the following passage in particular to be illuminating for Western audiences. Even so, disgust did not leave a lasting mark on my psyche until 1992, when, at the age of eight, on a flight to America with my mother, I was served the first non-Chinese meal of my life. In a tinfoil-covered tray was what looked like a pile of dumplings, except that they were square. I picked one up and took a bite, expecting it to be filled with meat, and discovered a gooey, creamy substance inside. Surely this was a dessert. Why else would the squares be swimming in a thick white sauce? I was grossed out, but ate the whole meal, because I had never been permitted to do otherwise. For weeks afterward, the taste festered in my thoughts, goading my gag reflex. Years later, I learned that those curious squares were called cheese ravioli. Asian foodways, especially Chinese foods, are often at the top of the "disgusting" lists - a combination of racism and deliberate misunderstanding of ancient foodways. For instance, lots of ancient Roman foods were also "gross," but are rarely consumed today, so modern Italians don't get the same level of derision. Many people like to argue that foods they find disgusting are "objectively" bad - but these same folks probably don't bat an eye at moldy congealed milk (blue cheese), partially rotten cucumbers (fermented dill pickles), or 30 day-old meat (dry aged steak). It's all about upbringing and perspective - something that folks who fail to recognize their own personal bias don't seem to get. And certainly, everyone is entitled to their own personal feelings on particular foods. For instance, despite several attempts, I can't stand the flavor of beets. But I know that, because I've tried them. "Disgusting" foods are often vilified by people who have never actually tried them. While immigrant foodways have often been the target of othering through disgust in the United States (see: Progressive Era Americanization efforts), for some reason the Whitest, most capitalistic of the historic American foodways - the 1950s - is the target of the same treatment today. Perhaps it is that in our modern era we have vilified processed corporate foods. And while I'm the first person to advocate for scratch cooking and home gardens and farmer's markets and all that jazz, there's much more seething under the surface of this than just a general dislike of gelatin. When processed foods first began to emerge in the late 19th century with the popularization of canned goods, they democratized foods like gelatin, beef consommé, pureed cream soups, and out-of-season fruits and vegetables that had previously been accessible only to the wealthy. Suddenly, ordinary people could afford to have salmon and English peas and Queen Anne cherries year-round - not just the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts of the world. After the austerity of the Great Depression and the Second World, the world seemed poised to combine those lingering ideas of what the wealthy ate with all the convenience modern technology could offer. Certainly, as some have argued, corporate marketing and test kitchens played a major role in shaping what Americans ate. But just because it was invented for an advertisement doesn't mean Americans didn't eat it on a regular basis. By the 1970s, many of those miracle technologies such as canning, freezing, dehydrating, reconstituting, etc. had become hallmarks of affordable - and therefore poor - foodways. "Government cheese," canned tuna, white bread, canned vegetables, mayonnaise, boxed cake and biscuit mixes, and yes, gelatin and Cool Whip were what poor people ate. Wealthier people ate "real" food - a trend that continues today. Disdain for poor people and their food seems universal, but even today, certain poor people have their foodways elevated over others (namely, pre-Second World War European peasants and select "foreign" street food purveyors). People living predominantly subsistence agricultural lives are seen as "authentic," while their urban counterparts, who consume processed foods by choice or by circumstance, are "selling out." But even "authenticity" only goes so far with some people. And even when foodies pride themselves on "bravely" eating chicken feet and fermented fish and other foods many would deem "disgusting," there's still an element of othering and disdain at play, a loud proclamation of worldliness and coolness at eating what their peers might avoid, that has little to do with actually understanding the culture behind the food. The food of the 1950s, once the clean, efficient, technologically advanced wave of the future quickly became the purview of the poor and working class. And while mid-century foodies like MFK Fisher and James Beard and (to a lesser extent) Julia Child descried processed foods and hailed European cuisines, peasant and "haute" alike, the vast majority of ordinary people ate ordinary, processed foods, and tried recipes dreamed up by home economists in corporate test kitchens. And within two decades, once the futurism wore off and the affordability factor set in, it became perfectly acceptable, cool even, to deride and mock those foodways. Which brings me back to the tuna on waffles. Canned tuna in cream of mushroom soup on top of hot, crisp waffles (probably NOT frozen, as frozen waffles weren't invented until 1953) is not something most of us are likely to eat on a regular basis today. However, it is hearkening back to a much older recipe: creamed chicken on waffles, which dates back to the Colonial period in America. Although the history of creamed chicken on waffles isn't crystal clear, this dish is clearly what Campbell's was emulating with their recipe. But what's the disgust factor? How is creamed tuna on waffles different from a tuna melt? Creamed chicken and biscuits? Fried chicken and waffles? Perhaps it is because today we associate waffles exclusively with sweet breakfast foods, so the idea of savory waffles is baffling. But they've only been used that way for a fraction of their history, for most of which they were used much more like biscuits or bread than a dessert. Or perhaps it's the tuna? Despite being hugely popular in the 1950s, tuna has fallen out of favor nationwide. Concerns about mercury, dolphins, and its association with poverty have helped dethrone tuna. But in the 1950s, it was a relatively new, and popular food. Today, it's a "smelly" fish associated with cafeterias and diners and cheap meals like tuna noodle casserole. Maybe it's the canned cream of mushroom soup? Cream of whatever soups remain a popular casserole (hotdish, for my fellow Midwesterners) ingredient even today, and the ability to replace the more labor-intensive white sauce with a canned good has helped many a housewife. Today, canned soups are vilified as laden with sodium and, for the creamy ones, fat. But canned goods have also been scorned as poverty food, with modern foodies touting scratch made sauces and fresh vegetables as healthier and better tasting. In the context of the 1950s, fresh vegetables were not always widely available as they are today, so canned and frozen vegetables took the drudgery out of canning your own or going without. In fact, our modern food system of fresh fruits and vegetables is propped up by agricultural chemicals, cheap oil, watering desert areas, and outsourcing agricultural labor to migrant workers or farms in the global south. Something many foodies like to conveniently overlook. My ultimate point isn't that people shouldn't reject processed foods in favor of scratch cooking. Indeed, I think that anyone who can afford to cook from scratch, should. But there's the rub, isn't it? Afford to. Because as much as homesteaders and bloggers and foodies like to proclaim that cooking from scratch is cheaper and healthier, it requires several ingredients they take for granted that aren't always available to everyone - a kitchen with working appliances, adequate cooking utensils, access to a grocery store and the means to transport fresh foods (fresh fruits and vegetables are HEAVY), the skills to know how to cook from scratch effectively and efficiently, and most importantly, TIME. As the old adage goes, you can have good, fast, and cheap, but never all three at once. Good and fast is expensive, good and cheap takes time, and fast and cheap is usually not very good. And when you're working multiple jobs to make ends meet, getting decent-tasting food on the table in a timely manner is more important than worrying about cooking from scratch. Those were the same concerns many working class people in the 1950s had, too. Even though the stereotypical White 1950s housewife had plenty of time to cook from scratch, plenty of women, especially women of color, worked outside the home in the 1950s. And mid-century Americans spent a far higher percentage of their income on food than they do today. And while fast food was around in the 1950s, it wasn't particularly cheap. For most Americans, it was an occasional treat, and restaurant eating in general was reserved for special occasions. Casual family dining as we know it today didn't exist. So that meant the typical housewife, wage working or not, had to cook 2-3 meals a day, nearly 365 days a year. Is it any wonder they turned to processed foods where most of the work was done for them? Maybe I've got a little personal bias of my own - after all I was raised in the land of tater tot hotdish and salads made with Cool Whip (That Midwestern Mom gets me). Foods that are often vilified by (frankly snobbish) coastal foodies, but that are "objectively" quite delicious. I like melty American cheese on my burger and grilled cheese as much as I enjoy making a scratch gorgonzola cream sauce. Fruit salad made with Cool Whip is a fun holiday treat. And while I prefer to make my own macaroni and cheese from scratch, I'd never mock or turn up my nose if someone offered me Kraft dinner. I think the driving force behind this pet peeve of mine is the idea that anyone can be the arbiter of taste (or disgust) when it comes to someone else's foodways. As my mom always used to say, "How do you know you don't like it if you don't try it?" Everyone's food history deserves respect and understanding. So let's give up the mean girl attitudes about foods we're not familiar with and let go of the guilt about liking the foods we like, be they 1950s processed foods or 500 year old family recipes. And the next time someone talks about how "gross" or "disgusting" a food is, or goes "Ewwww!" when presented with something new, give them a gimlet eye, ask them if they've ever had the dish, and then ask, "Who are you to judge?" The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!