|

Today's World War Wednesday poster is one of the more whimsical food posters created during World War II. "Lick the Platter Clean, Don't Waste Food" features a tall, thin man and a short, stout woman showing a shining clean brass platter. They are both dressed in old-fashioned, even Medieval-looking clothing, as befitting fairy tale characters. Of course, they are Jack Sprat and his wife, from the famous nursery rhyme: "Jack Sprat could eat no fat, his wife could eat no lean, but between the two of them, they licked the platter clean." The fairytale cartoon style is distinctive to artist Vernon Grant, who is probably best known for creating the original "Snap, Crackle, and Pop" characters for Rice Krispies cereal in 1933. The use of cartoons during the Second World War to promote propaganda ideals was not uncommon, and even Walt Disney and his animators got involved. Like hearkening back to the patriotism of the American Revolution, the use of fairy tales and other common childhood references were a clever way to remind people of pre-existing frames of reference for the behavioral changes the government was requesting of everyone. The message, of course, was a frequent one, although more often directed at soldiers and seamen than ordinary Americans, for whom the focus was more on food storage and cooking than eating. But the idea of not wasting food you took remains even today, when parents exhort their children to clean their plates. Did you grow up with the Jack Sprat rhyme? Were you told to clean your plate growing up? Let us know in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

0 Comments

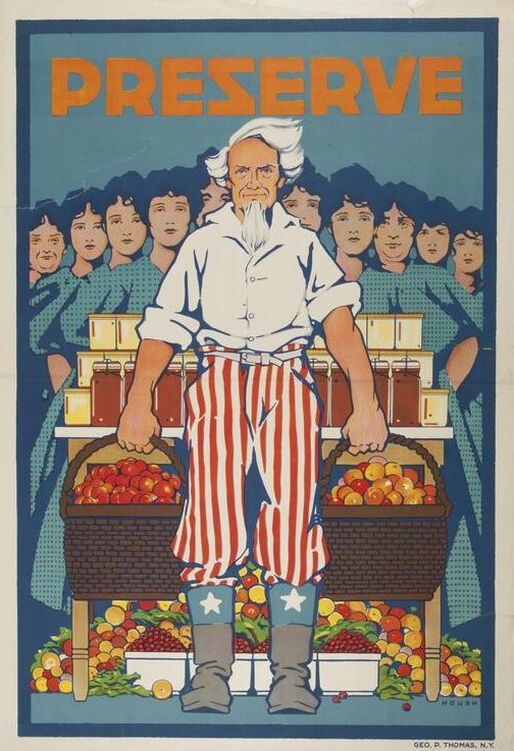

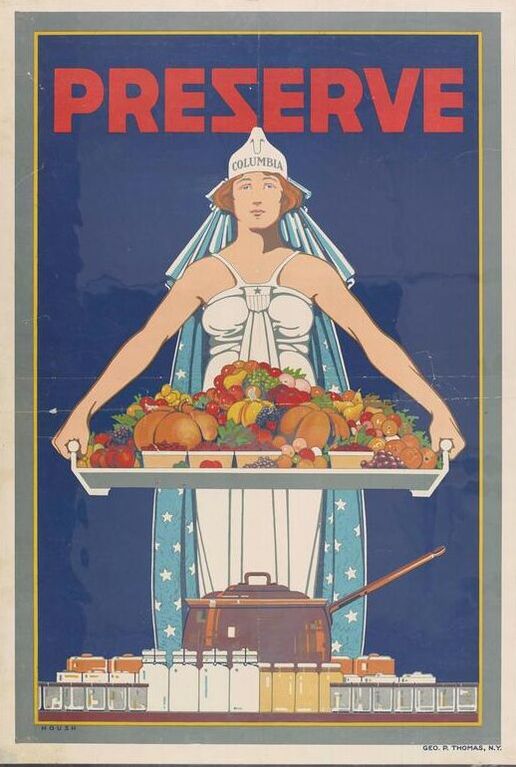

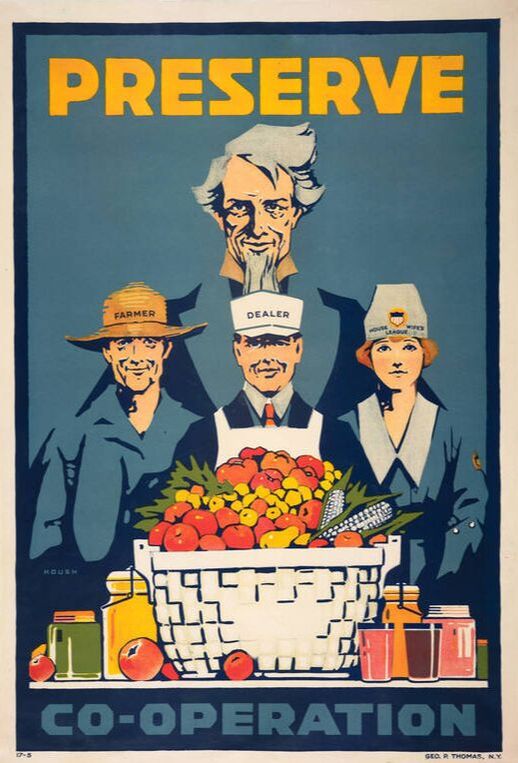

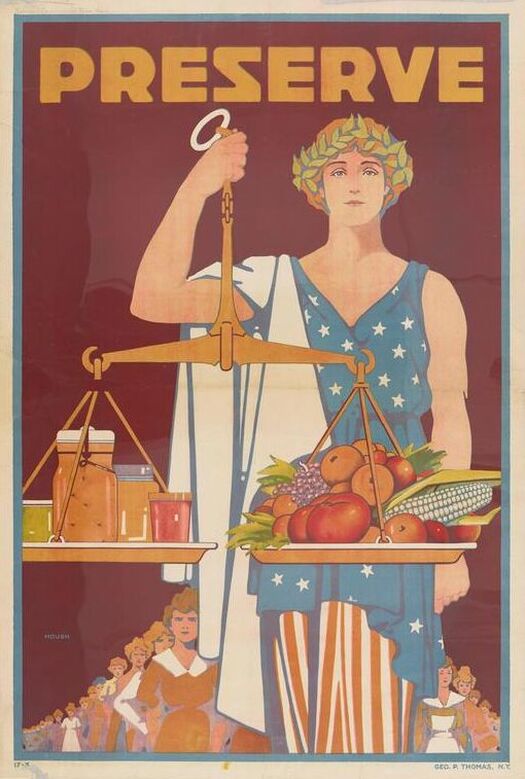

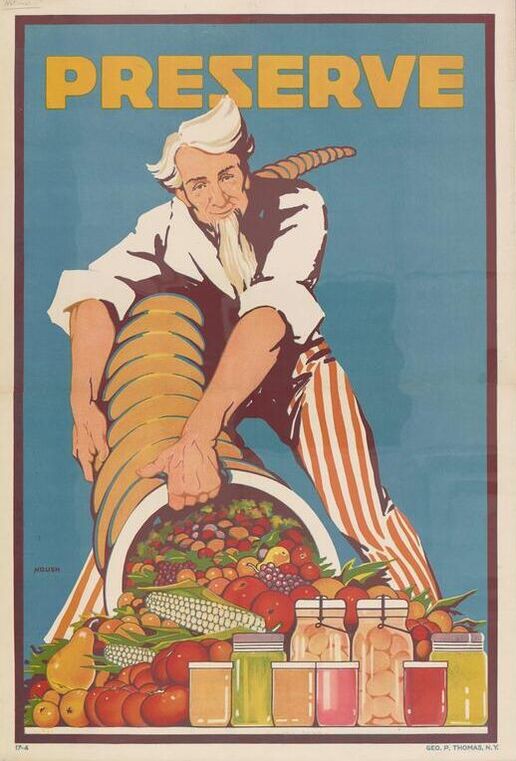

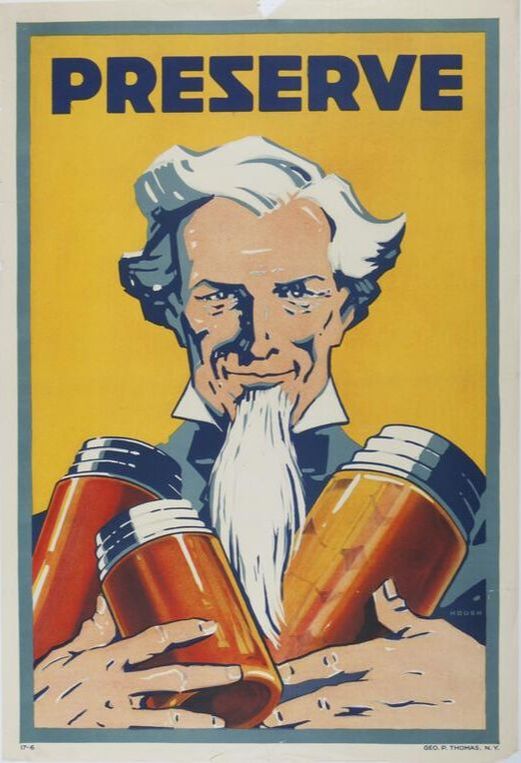

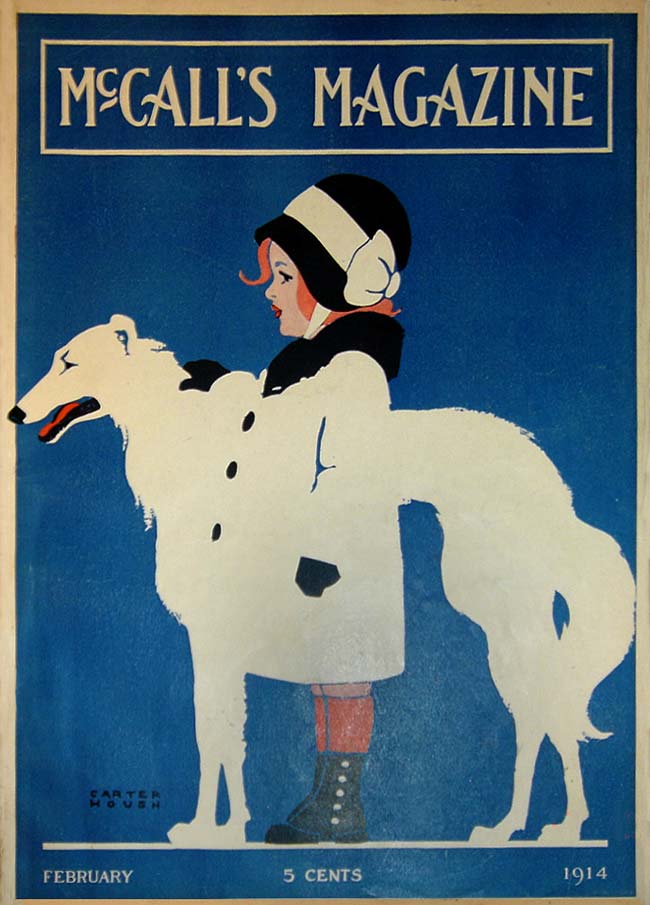

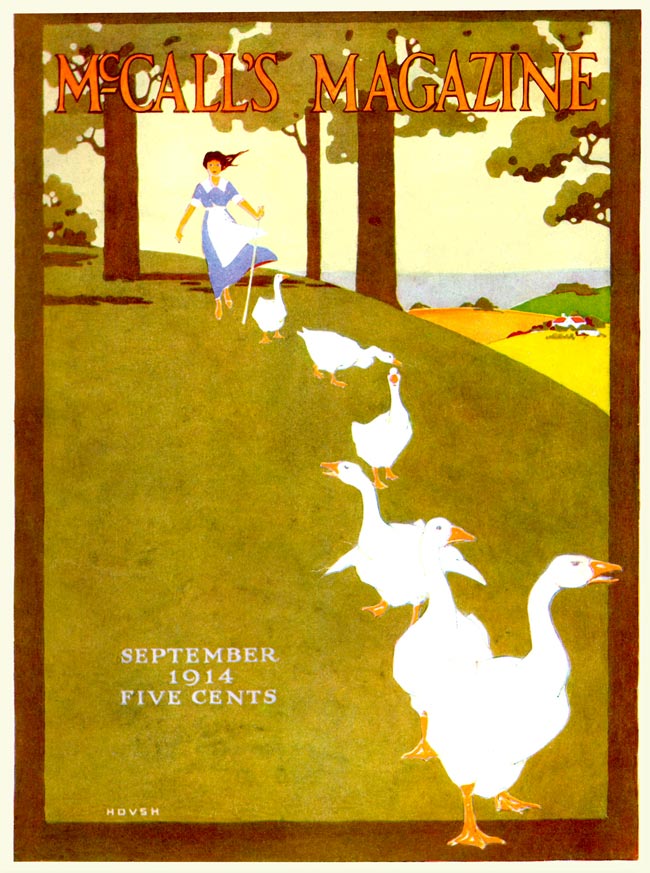

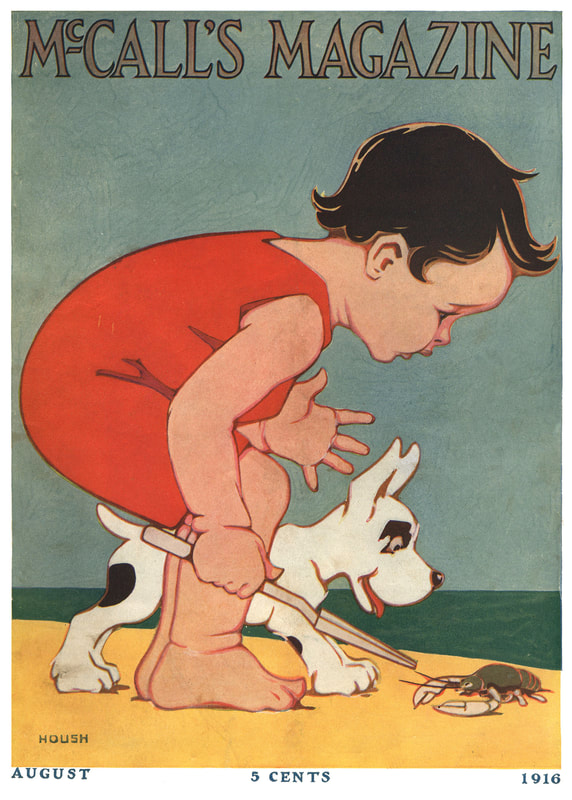

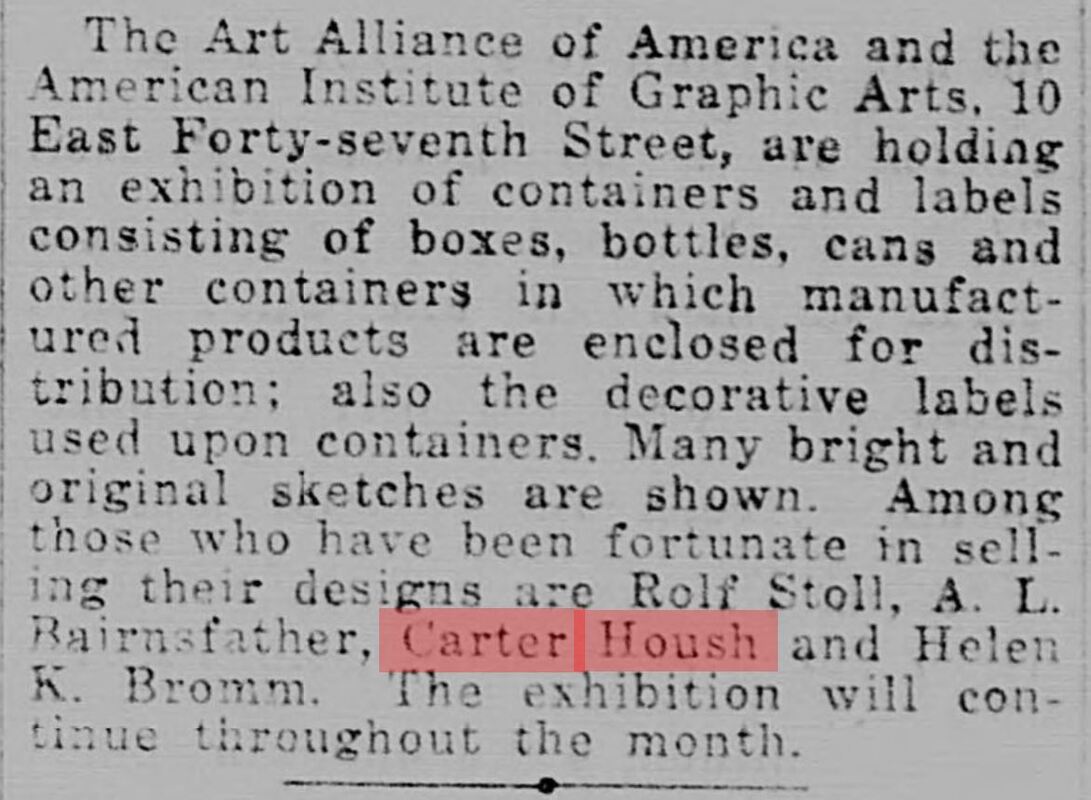

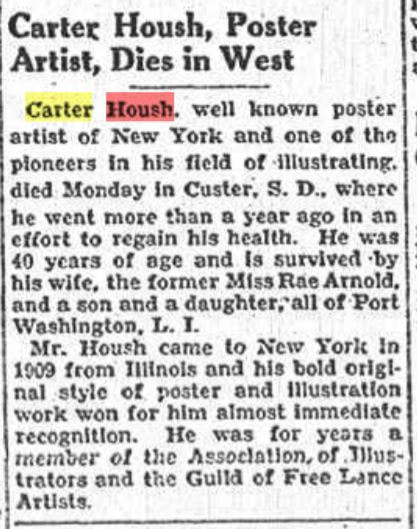

Note: This article was originally published on February 12, 2020 and has been updated with new information! If you haven't figured it out by now, I really love propaganda posters. Especially those from World War I. But my absolute favorite poster artist is one no one seems to know anything about.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, Uncle Sam, in his trademarked striped trousers but without his blue frock coat stands in his shirtsleeves, rolled up to the elbow, holding baskets full of fruit. Behind him is a table laden with full canning jars, with fruit and vegetables overflowing a pile beneath the table and behind that an army of women all dressed in blue. Missouri Historical Society. Carter Housh was apparently born in 1887 and died in 1928. And aside from an illustration or two for McCall's magazine, he is known ONLY for these six propaganda posters, encouraging Americans to preserve food during the First World War.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, a white-clad Columbia, goddess of America, with her French liberty cap and a star-spangled cape holds a massive tray laden with fresh fruits and vegetables. Below, an enormous handled saucepan and empty jars lined up before her, ready for filling. USDA Library Archive. As far as I can tell, nowhere else on the internet are all six of these posters displayed together. In fact, three of them were new to me! I discovered them as I was doing research on Housh, so that was delightful.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. Here, Uncle Sam, again in his blue frock coat, looms behind three figures - a farmer in a straw hat, a "dealer" or greengrocer in white cap and apron, and a woman dressed in the official food preservation uniform with a white cap that reads "House Wife's League" stand before him. An enormous white basket of fresh produce, flanked by filled canning jars, sets on the table before them. Underneath reads "Co-operation," implying that preservation needs the cooperation of the farmer, the retailer, and the housewife, all under Uncle Sam's watchful gaze. Missouri Historical Society. Housh's work has been called "modern" before, but aside from the font with it's rather Z-looking S, the imagery and style seems very typical of the period. I love Housh's use of shadow and color-blocking and his depictions of produce are simply divine - perfect, gleaming, and blemish-free. Quite unlike the real world, alas. I particularly enjoy Housh's depictions of people and Uncle Sam is no exception. Uncle Sam was long used to represent the United States, but during the War James Montgomery Flagg's depiction in his famous "I Want YOU!" poster helped lead to a resurgence in use of Uncle Sam to represent the U.S. I'm particularly fond of Housh's version because he's less scrawny and stern looking than other incarnations. Plus, when he's hard at work, shirtsleeves rolled up, his hair gets a particularly nice wild swoop to it. One that isn't present in his more sedate depictions, like the poster below. One interesting thing about this time period is that both Uncle Sam and Columbia were used to represent the United States. The First World War is one of the last times the Greek-inspired secular goddess would be broadly used to represent America.  "Preserve" by Carter Housh. In this image, a different incarnation of Columbia, in a gown of star-spangled blue, red and white stripes, with a white draped sleeve and a crown of laurel, holds enormous scales depicting canned goods and fresh produce in balance. Lined up behind her stretching out into the distance is a variety of American housewives in varying dress. USDA Library Archives. As much as I love Uncle Sam, of course I prefer Columbia because she is just so Progressive Era - an inspiring mix of Greco-Roman, feminist, Romantic representation that doesn't exist anymore. Of course, today's American goddess would look quite a bit different, and probably would not be named after Columbus, and that's equally as wonderful. If you want to know more about Columbia, check out this overview from the Atlantic. Which of these beautiful posters is your favorite? And if anyone happens to find anything on Carter Housh (or his printer, George P. Thomas of New York), please send me the info! Update - more about Carter Housh!Apparently Susan Jackson took my request to heart! Here's what she has to say about Carter Housh, her grandfather! Carter Housh was my mother's father. He was married to Rae (Arnold) Housh Enright. He died when my mother, Barbara Belle (Housh) Gibson, was 13. He left due to illness and went out to South Dakota where he died. He also had a son, David Paine Housh, my mother's younger brother. His wife, Rae, remarried another artist, a political cartoonist and author of children's books, Walter J. Enright. I do not have much information on Carter otherwise, sadly, nor do I have a good picture of him (so far.) Thank you, Susan, for sharing this great biographical info! I did do a little more digging to see what else I could find and I did find a few more references, although fewer than you might expect. In 1910 he appeared to work as an illustrator for the Sunday edition of the Buffalo Times based out of Buffalo, New York. He also worked for several years for McCall's magazine between 1910 and 1916, leaving evidence of several magazine covers, courtesy Flickr and Magazineart.org, a delightful website mentioned in one of the Flickr postings. We see no further known references to Carter Housh until 1918, the height of the U.S. involvement in World War I, when he is mentioned in an exhibition of artists as one of the few people who sold designs. 1918 is also the date attributed to his stunningly beautiful "PRESERVE" poster series. The Art Alliance of America and the American Institute of Graphic Arts, 10 East Forty-seventh Street, are holding an exhibition of containers and labels consisting of boxes, bottles, cans and other containers in which manufactured products are enclosed for distribution; also the decorative labels used upon containers. Many bright and original sketches are show. Among those who have been fortunate in selling their designs are Rolf Stoll, A. L. Bairnsfather, Carter Housh, and Helen K. Bromm. The exhibition will continue throughout the month. Carter Housh died on Monday, May 14, 1928 in Custer, South Dakota. Two obituaries in New York newspapers were published, likely due to his connections to New York City and Buffalo, NY when he was an illustrator. One, "Carter Housh, Poster Artist, Dies in West," published in the New York Sun on May 16, 1928 reads: Carter Housh, Poster Artist, Dies in West Another obituary, "Carter Housh Dead," was published in the New York Times, also on May 16, 1928. Carter Housh Dead Clearly the New York Times was less interested in accuracy than the Sun. It is sad to learn his life was cut so short and one wonders what illness he died of. Still, he leaves a legacy of stunning art and his posters remain my favorites of the entire war. If anyone finds any more breadcrumbs, send them my way and I'll update again! And, as always, if you enjoyed this post, please consider becoming a member of The Food Historian. You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

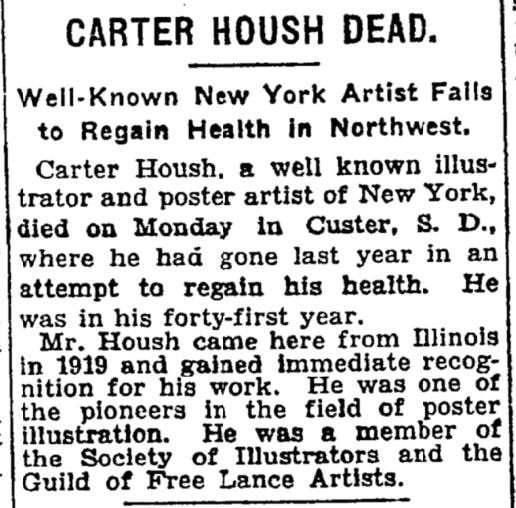

Thanks to everyone who joined me for Food History Happy Hour this month. We talked about all things Irish and food, including the origins of corned beef, Irish soda bread, the Irish Potato Famine, Irish slavery and prejudice, cabbage, brussels sprouts, and the role of brassicas in European and Asian cuisine, and we touched on carageenan or Irish moss pudding, scones and bannocks, Irish coffee, and Irish desserts.

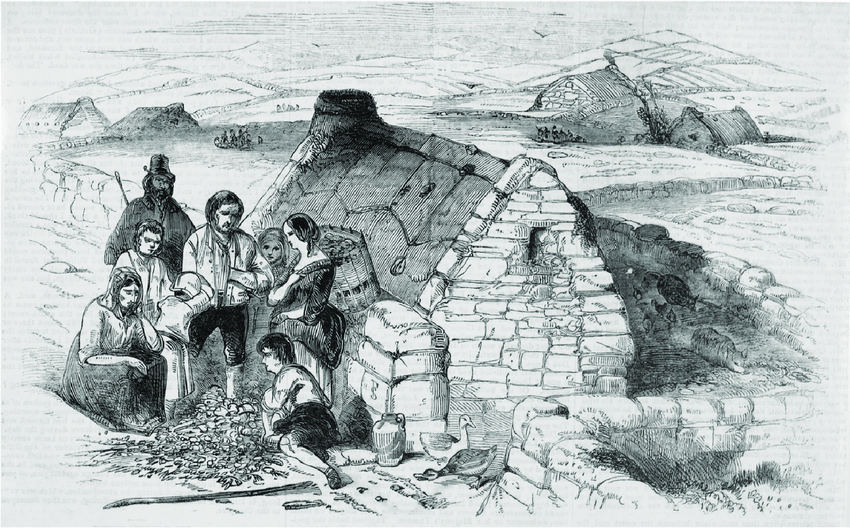

Irish Cocktail (1902)

Tonight's cocktail came from Fox's Bartender's Guide by Richard K. Fox (1902). The 1902 edition was preceded by The Police Gazette Bartender's Guide, first published in 1888, and with a much more interesting cover. Richard K. Fox was the Irish immigrant publisher of The Police Gazette, widely considered the one of the first men's magazines, and which covered tabloid-style sensationalist news, manly (and illegal) sports such as boxing and cockfighting, coverage of vaudeville shows, and "girlie" images of burlesque dancers and other ladies of ill repute.

The cocktail itself is called "Irish" because of the use of Irish whiskey, which also features in several other cocktail recipes. Fox (or whomever was authoring the recipes) seemed rather fond of both absinthe and especially curacao, which feature prominently in most of the cocktail recipes. I won't replicate my version of this recipe as I made a number of substitutes (some knowingly, some out of ignorance) and the end result was not to my taste. Perhaps your version will be better!

Irish Cocktail.

Use large bar glass. Fill glass with shaved ice. Two dashes of absinthe. (or anisette) One dash Maraschino. (the liqueur, not the cherries) One dash Curacoa. (he means Curacao) Two dashes bitters. One wine-glassful of Irish whiskey. (probably 2 ounces) Stir well with spoon, and after straining in cocktail glass, put in medium olive and squeeze lemon peel on top. (a.k.a. a twist of lemon) This cocktail took on a rather unappealing hue, in large part because modern Curacao, an orange-flavored liqueur, is colored bright blue (something that apparently dates to the 1920s). But even historically absinthe was green. Thankfully, Maraschino liqueur is clear. But blue, green, and brown (the whiskey) a muddy-looking cocktail make, so keep that in mind. Episode Sources & Further Reading

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

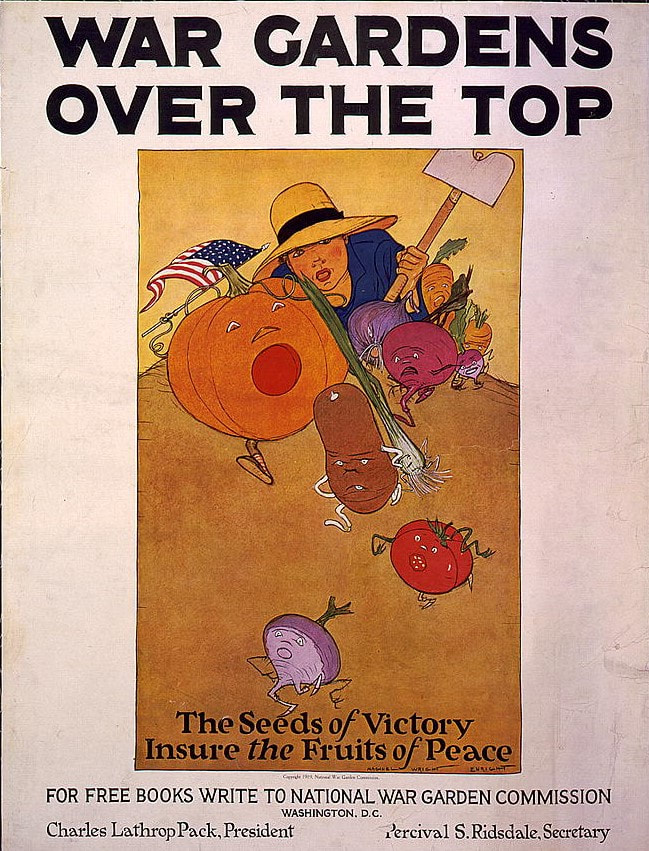

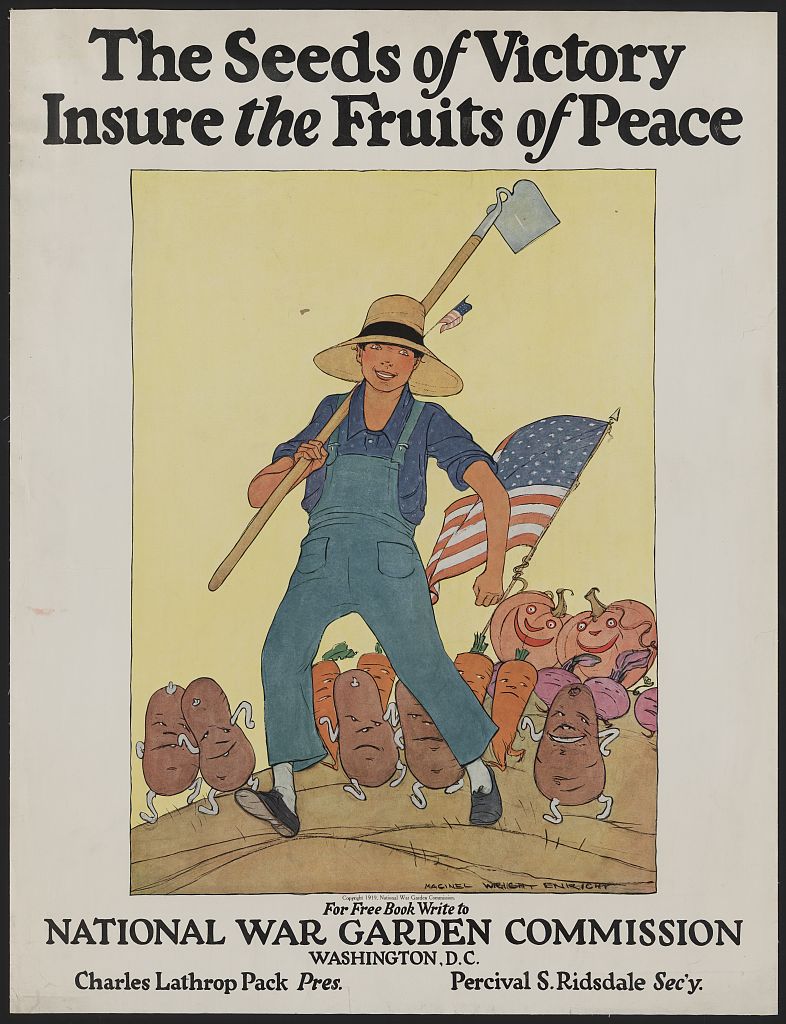

The National War Garden Commission, a private organization funded by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, was one of the most prolific sources of wartime propaganda posters outside the federal government. One of the major proponents of civilian garden programs, even before the U.S. entered the First World War, the National War Garden Commission gave away free booklets on gardening, canning, and food preservation. The above poster features a boy with a spade and straw hat climbing over a mound of dirt. In the lead are series of anthropomorphic vegetables, including a pumpkin carrying the American flag, and all appear to be yelling or screaming as they run down the hill. Reading "War Gardens Over the Top," and "The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace," the poster brings to mind the "boys" going "over the top" of the trenches in battle. This use of military language in propaganda posters was not uncommon, but this particular phrase likely did not have the full impact in the period that it does now. Today, we realize how horrific the charges of men "over the top" and across no-man's land between the trenches on the front really were. But in the period, it's likely people had only sanitized newspaper articles and perhaps a propagandized newsreel or two to give them a frame of reference for the term. In this second poster, which also reads "The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace," our military allusions are a little more innocent. Here our same overall-ed and straw-hatted boy marches in a parade, hoe over his shoulder, accompanied by more anthropomorphized vegetables. These vegetables look less than thrilled to be marching, but the sentiment is the same. Both posters were published in 1919, technically AFTER the war was over. But as with most wars, the end of conflict does not mean that everything goes back to normal. There were numerous attempts by a number of organizations, including the federal government, to get Americans to continue to conform to wartime measures, including voluntary rationing and war gardens, which were termed victory gardens after the cessation of hostilities, well in to 1919 and even 1920. Here, the National War Garden Commission makes the argument that the "seeds of victory insure the fruits of peace," meaning that by continuing to plant vegetable gardens and free up domestic food supply for shipment overseas, Americans could help stabilize and rebuild Europe in the wake of the war. Illustrated by Maginel Wright Enright, primarily known as a children's book illustrator, the posters have a luminous clarity, even if Enright was not particularly good at giving vegetables convincing facial expressions. Lots of folks are starting year two of pandemic gardens - are you one of them? I am! Raised beds are going in this year and I already have my seeds and a plan. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

George Washington Carver is a historical figure you may have heard of. Perhaps you grew up learning in elementary school that he invented peanut butter (he didn't), or perhaps you know his work in popularizing sweet potatoes. You might know he was born into slavery, and through his pioneering efforts at plant science, helped found the agricultural college at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

But the bulk of his accomplishments have been glossed over in popular culture, until now. Grist recently published an excellent overview of the real contributions Carver made, and why they have largely been ignored. George Washington Carver died on January 5, 1943. Just a few months before his death, he published Nature's Garden for Victory and Peace, his contribution to the victory garden conversation during the Second World War.

Many people wrongly attribute Carver's booklet as a guide to victory gardens. In fact, it is a guide to foraging, and in line with Carver's ideas about food sovereignty that were decades ahead of their time.

Carver knew that access to land meant access to food, and even if Black families were denied access to land to grow gardens, they could forage in the wild public spaces or unclaimed verges of roads, edges of fields, etc. Still coming out of the Great Depression in 1941, people were eager to supplement often meager food supplies however they could. Free food was worth the labor to collect and process it. Nature's Garden lays out not only the common and botanical names of many wild-growing and native greens and herbs, some with accompanying line drawings, but also advice for harvesting and processing, recipe suggestions, and advice on drying garden produce for long-term storage - cheaper and easier than canning, which required expensive equipment and jars. Carver also includes references to Indigenous food uses, such as the use of sumac in making "lemonade," and directions for how to make "Lye Hominy," using the nixtamalizing process invented by Indigenous peoples in Mexico to hull corn and make the naturally-occurring niacin in the corn absorbable by the human body. The booklet was given away free - one copy per person. Additional copies could be acquired at the cost of printing. A Simple, Plain, and Appetizing Salad

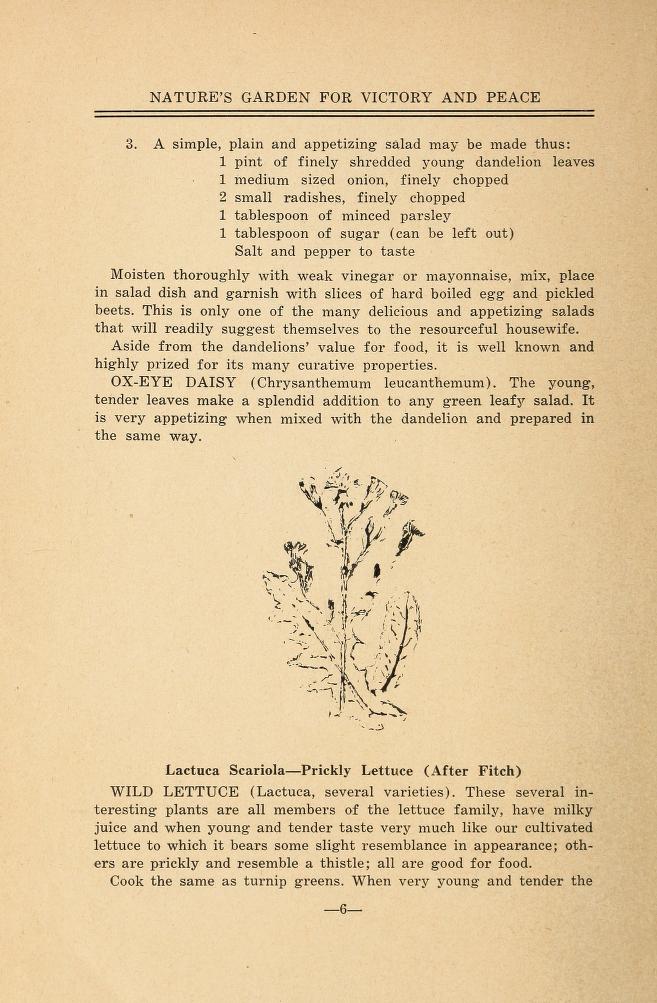

One of the few recipes Carver actually outlines in Nature's Garden is also one of the first - a recipe for dandelion salad.

It reads: "A simple, plain and appetizing salad made be made thus: 1 pint of finely shredded young dandelion leaves 1 medium sized onion, finely chopped 2 small radishes, finely chopped 1 tablespoon of minced parsley 1 tablespoon of sugar (can be left out) Salt and pepper to taste "Moisten thoroughly with weak vinegar or mayonnaise, mix, place in salad dish and garnish with slices of hard boiled egg and pickled beets. This is only one of the many delicious and appetizing salads that will readily suggest themselves to the resourceful housewife." A modern incarnation might be made with arugula, instead of dandelion leaves, if you are unable to forage your own safely.

Today, other foragers are trying to reclaim foraging for BIPOC communities. Alexis Nikole Nelson, also known as Black Forager, is one of those people. Like Carver, she reminds everyone that foraging has been the purview of BIPOC communities for as long or longer than the white male foragers who often get all the attention these days.

I love Alexis' near-daily posts and how she cooks the food she forages - the most important information and often left out of the foraging equation. She's been profiled by TheKitchn, and Civil Eats, but you can learn the most by just following her on Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, or Facebook. You can also support her work by becoming a patron on Patreon! Further Reading

To learn more about George Washington Carver, check out these excellent resources.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

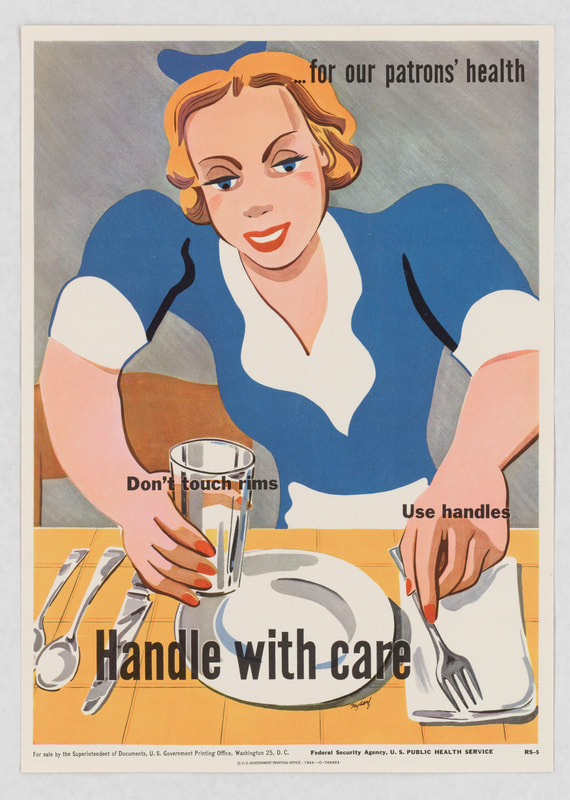

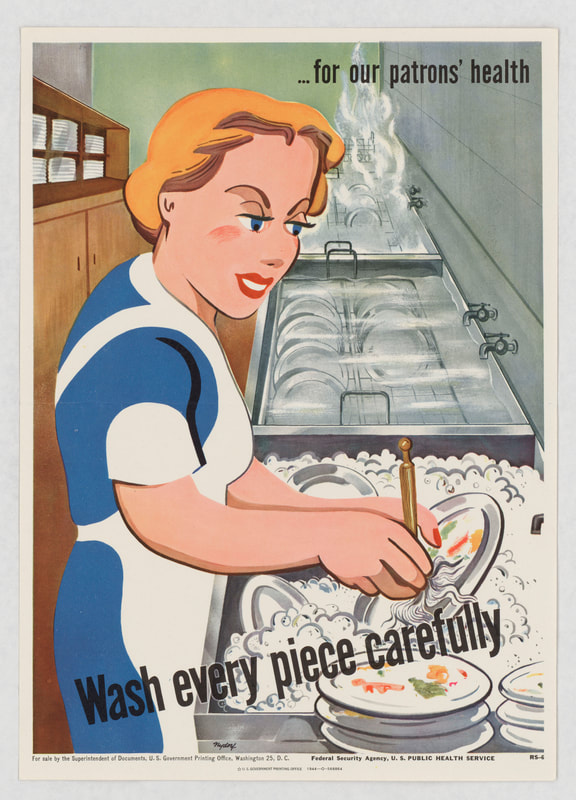

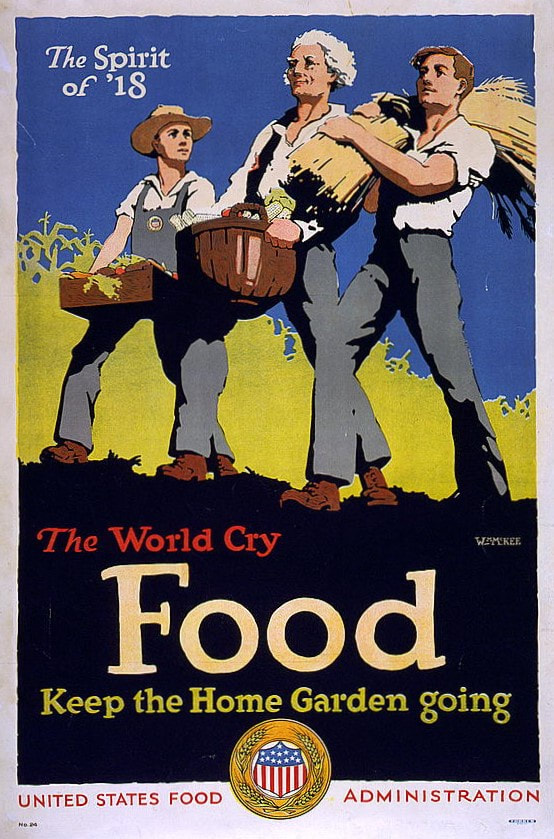

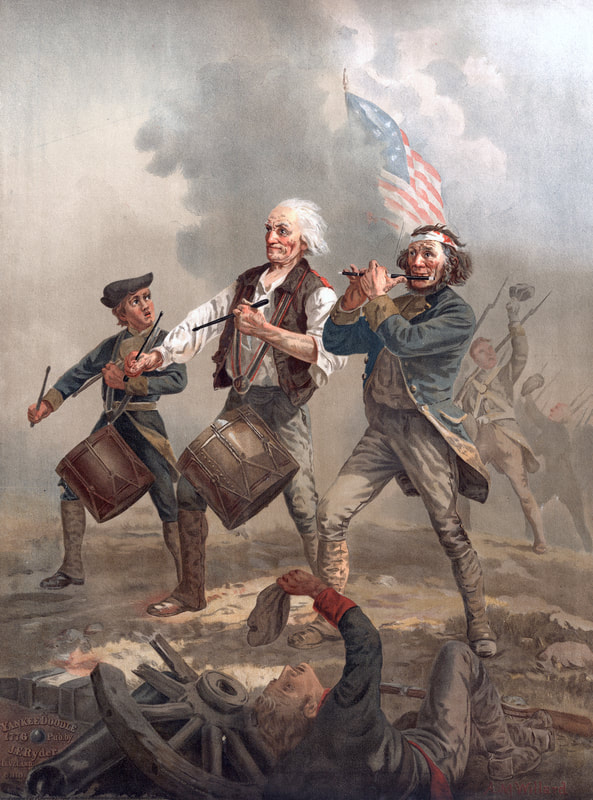

World War II propaganda posters were not only directed at individual Americans - they were also often directed at people involved in wartime work. And while factory workers might be the more popular images shown in books and documentary films, restaurant workers were a vital part of the wartime workforce. This series of posters was designed to encourage good hygiene and sanitation practices in restaurants, not only to conform with health department rules, but also to keep the workforce healthy and able to work. Produced by the U.S. Public Health Service of the Federal Security Agency, this series of six posters still resonates today! They were designed by artist Seymour Nydorf (1914-2001), who designed a number of posters for the Public Health Service. Featuring a blonde waitress in a blue uniform and different white aprons, with her little blue hat when in the front of house, the style of the illustrations is more stylized than strictly true to life, but makes the point all the same. As we are in the midst of a global pandemic, these posters seems particularly apt, especially this first one, exhorting restaurant workers to "Wash your hands often." This one, which encourages workers to "Use a fork - don't be a butterfinger," shows a waitress using a two-tined fork to take butter pats from a container of ice and placing them in little foil containers - much more sanitary than using her fingers. This poster, "Keep these under cover," shows a waitress adding a cup of pudding to a refrigerated case full of slices of pie, an eclair, and a salad - all things with cut edges that should not be exposed to air for fear of bacterial contamination. I'm sure we all hope that all restaurant workers still adhere to this advice! "Handle with care" shows a waitress placing a fork and cup at the place setting. The poster reminds her to "Don't touch rims" of glasses and "Use handles" to place cutlery. This poster, "Wash every piece carefully," shows a waitress washing a sink full of dirty dishes, with a rinse sink and possibly a steam sink, and shelves of clean plates behind her. This is an interesting scene to me because of the mop-like swab she is using to clean the plates, and what appears to be enormous racks of dishes in the sinks that can be lifted out. And finally, poster number six, "Keep these cold," shows our waitress placing a plate of cooked shrimp in the refrigerator with a whole shelf of milk bottles, a bone-in sliced ham, a square of gelatin, cups of pudding, and what appears to be a large dish of potato or macaroni salad. A thermometer indicating that the temperature is below 50 degrees Fahrenheit is prominently located in the foreground. All the advice in these posters still holds true today! Both in restaurants and at home. Except, these days, we'd have to add "wear a mask" to the list. But now, as then, restaurant workers have turned out to be much more essential than perhaps many people realized. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Last week we featured a propaganda poster from World War II that hearkened back to Valley Forge. This week we're featuring a propaganda poster from World War I that also hearkened back to the American Revolution - "The Spirit of '18." During the First World War, the United States Food Administration, along with private organizations like the National War Garden Commission, encouraged ordinary Americans to plant war gardens (later termed "victory gardens," a name that stuck when revived in the Second World War). War gardens were needed to free up commercial agricultural products to send overseas to American Allies, many of whom were suffering after three years of privations, and to feed American troops abroad. In particular, the 1915 and 1916 wheat harvests had been poor, leaving little to export. In order to free up domestic supplies for shipment overseas, the government encouraged Americans to grow and preserve more of their own food, alleviating the domestic strain on food supplies and freeing up commercial foods for government use. This was a tactic which was revisited during World War II. In this poster, a young boy wearing overalls bearing the US Food Administration seal, carries a wooden crate of vegetables. He looks on at the older man in the center, whose haircut brings to mind George Washington, and who carries a larger basket of produce. At the far right, a young man carries a sheaf of wheat on his shoulder. All are marching in step, a stylized cornfield and a brilliant blue sky behind them. "Spirit of '18," the poster reads at the top. Below, it says, "The World Cry Food - Keep the Home Garden Going," with the United States Food Administration title and seal at the bottom. Although it doesn't seem like it on the surface, this poster references the American Revolution. It is based on a very famous image which would have been familiar to Americans at the time. Painted by Archibald MacNeil Willard in 1875 for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the painting which became known as "Spirit of '76" was revealed to little critical acclaim, but great popularity among ordinary people. Willard reproduced it several times. The original was enormous - eight feet by ten feet. The above image of "Spirit of '76" is a chromolithograph produced by J. E. Ryder for the Centennial Exposition and sold to tourists as a souvenir (see the original here). This helped its popularity greatly, as it was widely panned by critics as too dark. The painting illustrates two drummers - one elderly and one a young boy, accompanied by a wounded man playing fife - behind them flies the American flag (or perhaps the Cowpens battle flag) and more troops waving their tricorn hats - evoking perhaps that the resolute fife and drum corps are leading a column of relief troops, bringing victory to the battle that wounded the artilleryman in the foreground with his cannon on the ground, its carriage broken. You can see how closely William McKee mirrored the work of Archibald Willard - the three figures in both images are nearly identical - a young boy, an elderly man, and a young man, although in the World War I poster the young man is considerably younger and more Adonis-looking than Willard's figure. The figures represent the three generations - youth, adulthood, and old age, as well as the breadth of men participating in the American Revolution and World War I. During the Revolutionary War, musicians were usually boys too young and men too old to enlist as regular soldiers. Old men and young boys were also "drafted" during the First World War for home front duties, including gardening and farm labor. In both images, the figures are marching forward, bringing victory behind them. Archibald Willard died on October 11, 1918, exactly one month short of the end of World War I. So it is possible he saw his work replicated in this poster. "Spirit of '76" was his most popular and enduring work, but it did not bring fame or fortune. For other Americans who saw the "Spirit of '18" poster, it surely would have instantly brought to mind the "Spirit of '76," and the sacrifices and courage of the American Revolution, inspiring similar levels of patriotism and sacrifice by Progressive Era Americans during the First World War to "do their bit" and contribute to the war effort through war gardens. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

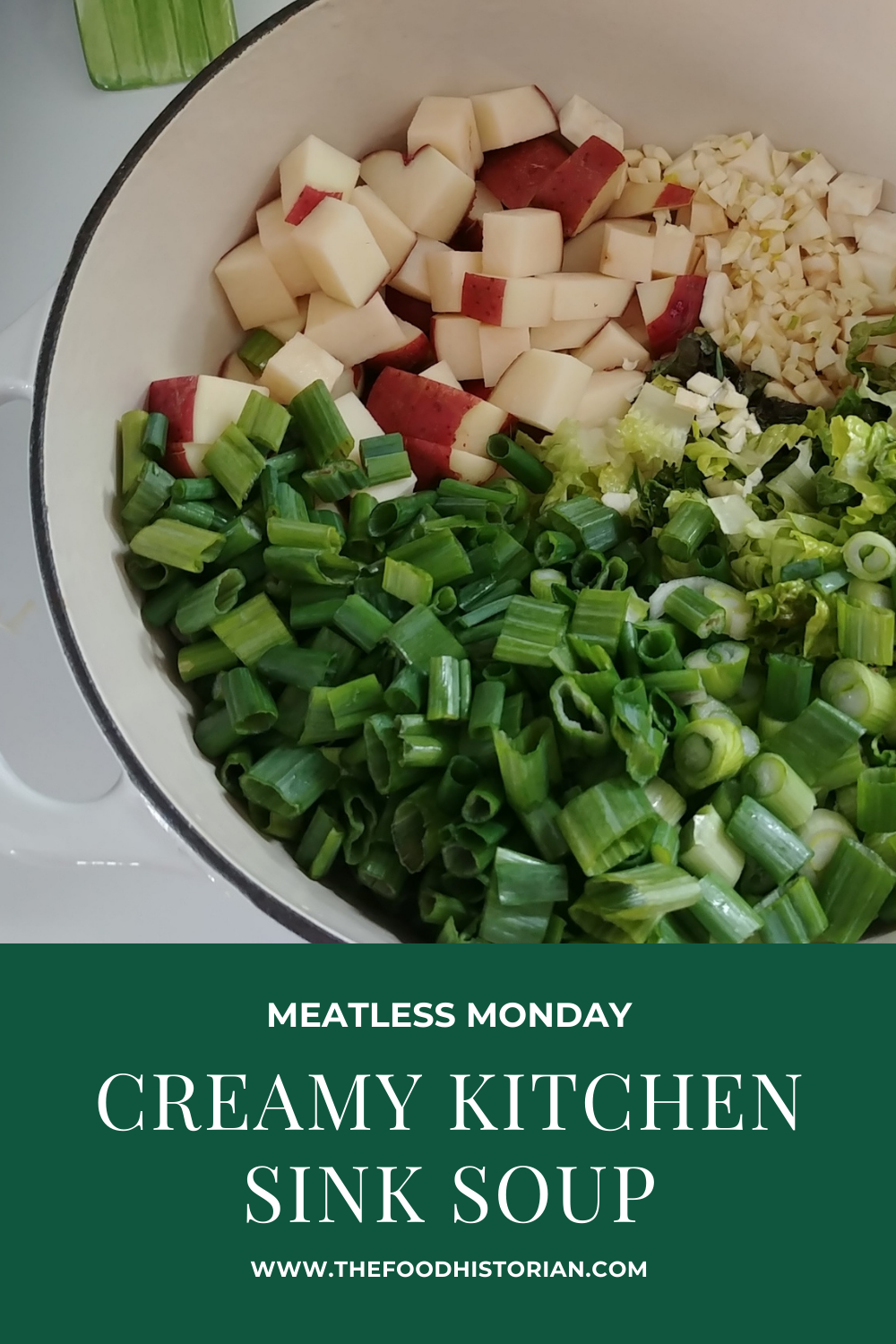

It's been cold and snowy lately here in the northeast, and sometimes you just have to have soup. But going to the grocery store in a snowstorm is ill-advised. This recipe lets you use up all kinds of bits and ends that might be languishing in your refrigerator.

This particular recipe is my own creation, based on what was in my kitchen, but is entirely inspired by history. Several parts of history, in fact. The first is reducing food waste. Historical peoples did not throw out potatoes just because they were starting to sprout, or lettuce because it was a bit wilted, and neither should you. Putting lettuce in soup is also extraordinarily historic, and a practice that should be revived. Another is that this recipe is based on one of my favorites, "Green Onion Soup," from Rae Katherine Eighmey's Hearts & Homes: How Creative Cooks Fed the Soul and Spirit of America's Heartland, 1895-1939 (2002). Eighmey read hundreds of agricultural magazines and gleaned recipes and wisdom from the farm home sections. Found in the December 26, 1924 issue of Wallace's Farmer, Green Onion Soup is a unique recipe. A combination of simply green onions and potatoes, the soup is cooked in a small amount of water, and then partially mashed right in the pot without draining. Cream and milk are added to thin the soup and add richness. The soup is comforting and nourishing and retains all of the vitamins and minerals that might otherwise be lost by draining away the cooking water. Which brings me to the final inspiration - vitamin retention in the style of recipes from World War II. By cooking the vegetables in the water that becomes the broth, you lose far fewer nutrients and flavor. Plus, other aspects of the soup are also quite appropriate to WWII - it's meatless, in line with rationing, and makes good use of milk, a favorite 1940s ingredient. Creamy Kitchen Sink Soup Recipe

I had a number of foods that needed using up that made their way into this soup: a few red potatoes, a head of wilted red lettuce, the fresh bits of baby spinach out of a box that was on the verge of getting slimy, a whole celery root starting to go a bit soft, some garlic starting to go green in the middle, and the tail end of a gallon of milk. The only fresh addition was two bunches of green onions. You could modify it pretty much however you want - any kind of greens, any kind of onion, any kind of root vegetable.

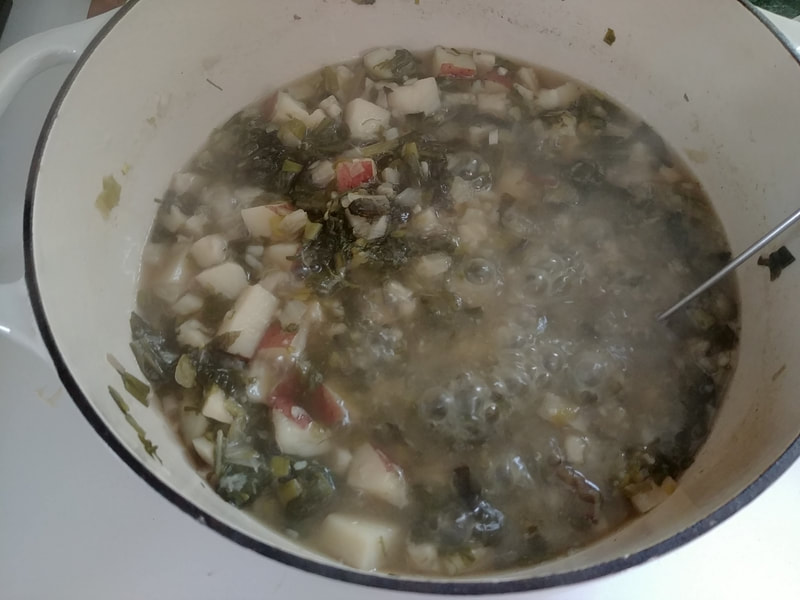

4 red potatoes 2 bunches green onions (scallions) 1 celery root 3 cloves garlic 1 head red lettuce 1-2 cups baby spinach water salt pepper 1/2 cup half and half 1 cup buttermilk whole milk Scrub and dice the potatoes, cutting away any eyes or bad parts, but leave the skin on. Slice the green onions, white and green parts. Cut away the knobbly skin from the celery root, then cut into small dice. Mince the garlic, wash and chop the whole head of lettuce. Add it all, with the spinach to a large stock pot and add water not quite to cover. Add at least 1 teaspoon salt (I used wild garlic flavored crystal salt languishing in a drawer) and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer hard until all vegetables are very tender and potatoes fall apart when pierced with a fork. Do not drain. Using a potato masher or sauce whisk, mash vegetables in the pot until blended with the water, leaving some chunks. Add a the half and half and buttermilk (or you could use part heavy cream, or leave out the buttermilk, or just use milk) then add milk to thin out the soup and to taste. Taste for salt and add more if necessary, along with pepper and whatever other herbs and spices you like. Serve nice and hot with buttered bread or toast. The buttermilk does add a nice, distinctive tang. If you don't have any, add a dollop of sour cream, or some plain yogurt, or a splash of lemon juice. You could make this vegan with plant-based milk and butter. For a different flavor, add whatever fresh herbs you have lying around - dill, parsley, basil, and cilantro would all be good here. Add vegetable broth and some lemon juice instead of milk for a bright, brothy soup instead of something creamy. Use sweet potatoes or squash and tomato broth with the greens. The possibilities are really endless.

If you'd like more interesting recipes, you can purchase Eighmey's book from Bookshop or Amazon - either way, if you do, your purchase will support The Food Historian!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed