|

Yes, dear readers, I bought myself a birthday present. I was so excited, too! I had read an article about this cookbook a while ago, and was delighted to find it in print with what I thought would be some historical analysis. Alas, I was very wrong. This is one of those things where someone takes a public domain cookbook, puts a modern spin on the layout, and pretends it's new. SIGH. I hesitate to even call this a review, as I won't be recommending much about my present to myself. I purchased "Vintage Vegan: Recipes From the World's First Raw Vegan Restaurant." It's attributed to Vera Richter, despite the fact that the actual title of the cookbook she published in 1925 (and again in 1948) was "Mrs. Richter's Cook-less Book." Vera Richter was a proponent of raw food and veganism and she and her husband John opened a raw vegan restaurant in Los Angeles, California sometime after 1918. And guess what! There's a Fargo, ND (my hometown) connection! John's father Frederick Richter (a trained pastor) became a physician and pharmacist there in the 1870s in the very early days of settlement. John later studied the sanitarium style healthcare pioneered by John Kellogg and started treating his father's patients with natural cures. He married Vera in 1918 and they moved to California where they opened a restaurant they later calledv"Eutrophion," which is apparently Greek for "good nourishment." It's a pretty fascinating story and apparently the restaurant was fairly influential in LA's early health food and body building scene. But of course, none of that is included in the book. Which is a pity, because with a little effort the reprint could have been wonderful, instead of disappointing. Essentially, the "editor" of the cookbook, wrote a 2 page intro which reads like a Wikipedia article (except the actual Wikipedia article is more extensive) and added a couple of editor's notes on the recipes. The editor is also quite clearly a proponent of raw veganism, and thus takes any and all claims at face value, and adds a few of her own. I'm not really sure why I was so convinced it was going to be a history of the cookbook and the restaurant with the recipes included. Just another case of expecting food history where clearly there is none! Sadly, so much context could have been given about California in the 1910s (when the restaurant was opened), the history of veganism and raw foodism in the United States and elsewhere, why California, etc., etc. Thankfully Mrs. Richter's actual cookbook is quite interesting, although her egg-less mayonnaise calls for the use of a ripe banana - not sure the taste is quite the same. But fascinating nonetheless. If anyone is looking for good raw vegetable salad recipes, this is the place to visit. But maybe, visit the original, instead of buying the reprint. And if you want to know more about Mrs. Richter? The LA Weekly has you (and me) covered. And, as always, if you enjoyed this post (and want to celebrate my birthday!), please consider becoming a member of The Food Historian. You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

0 Comments

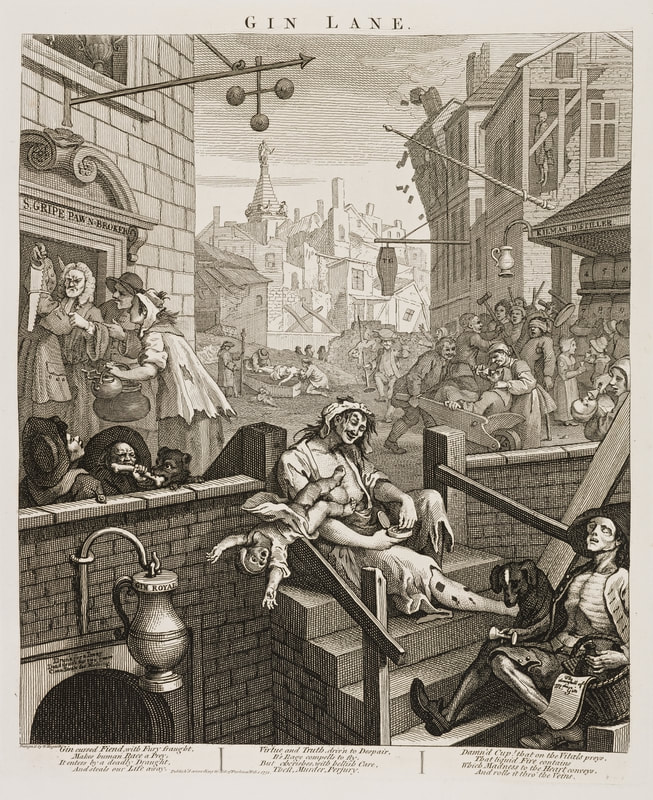

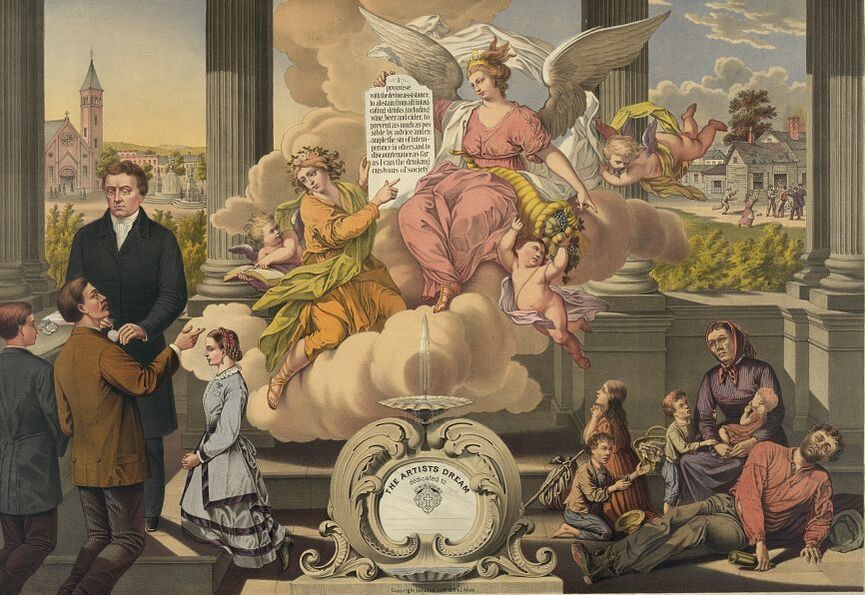

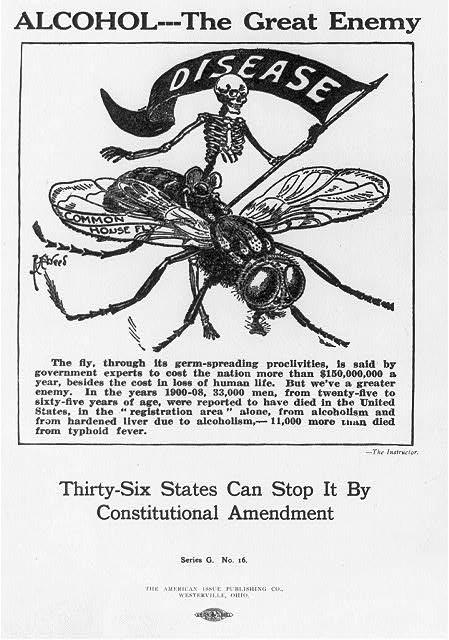

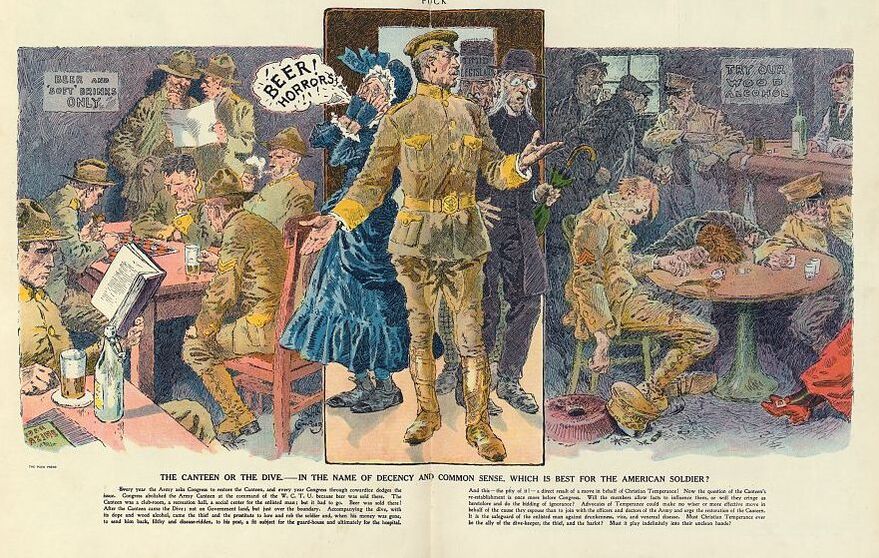

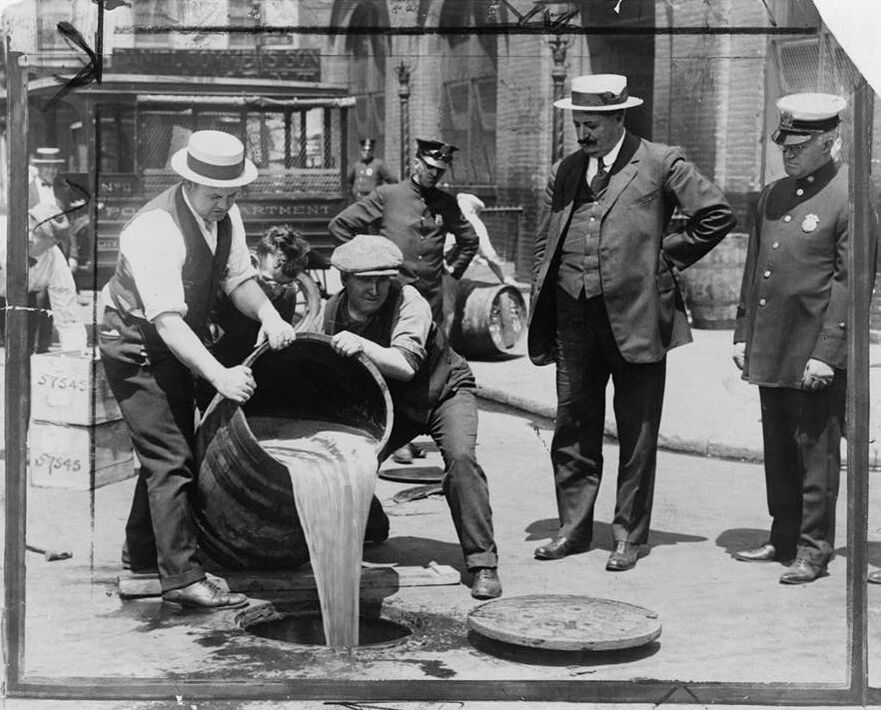

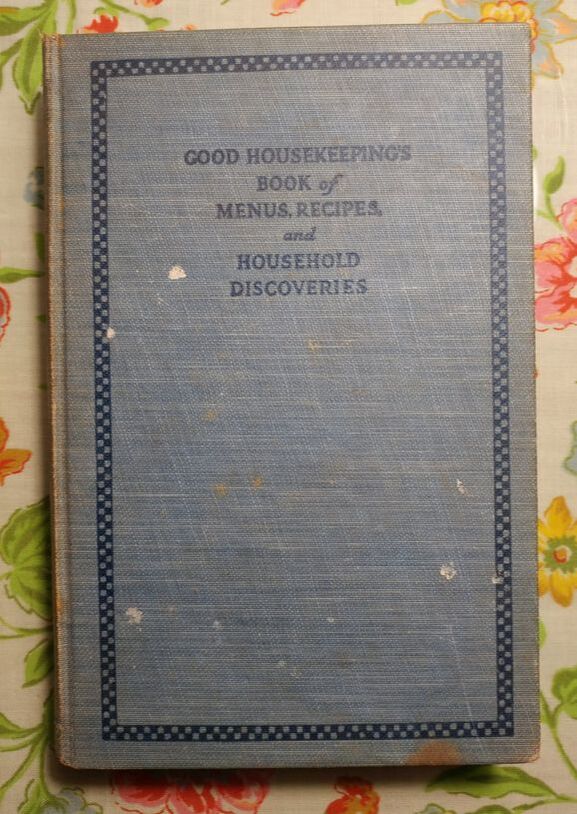

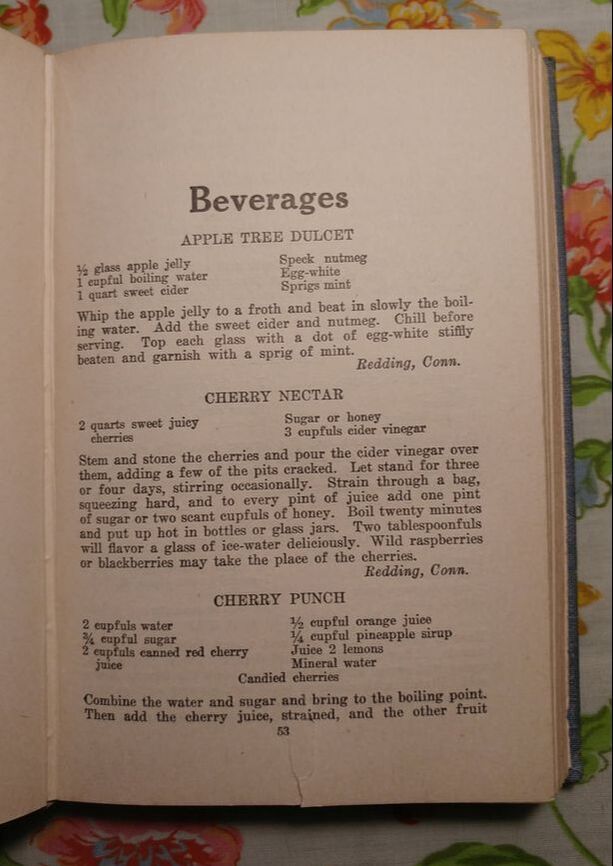

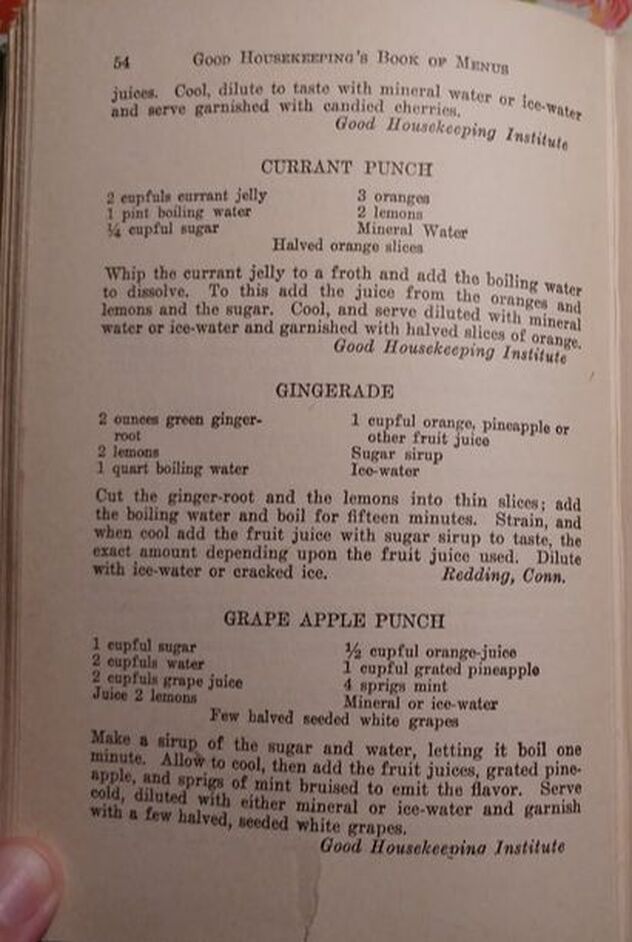

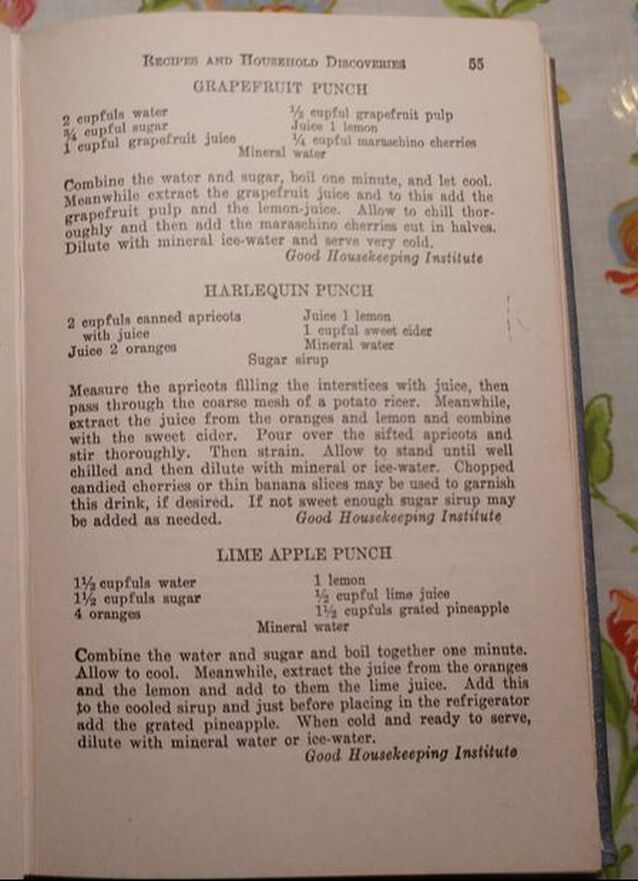

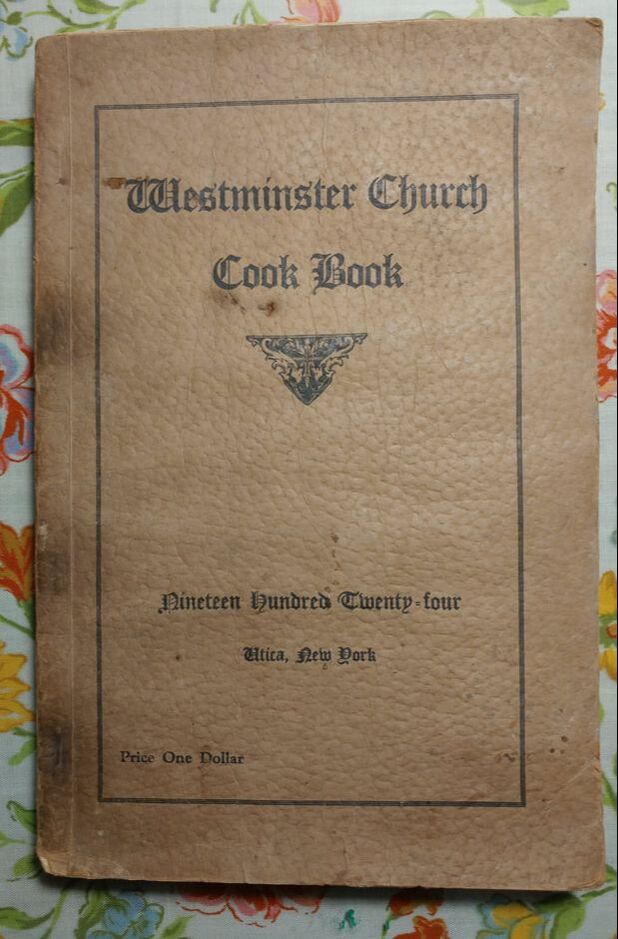

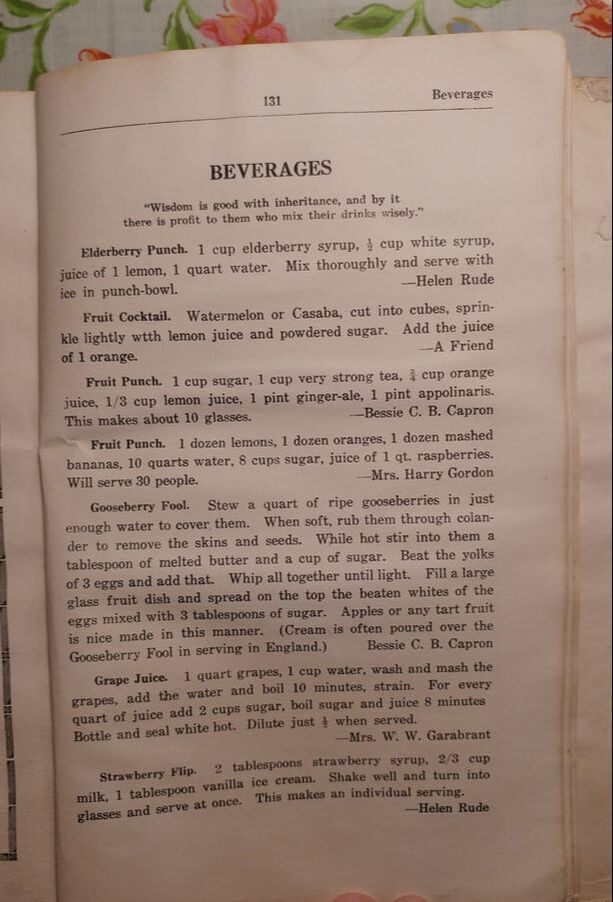

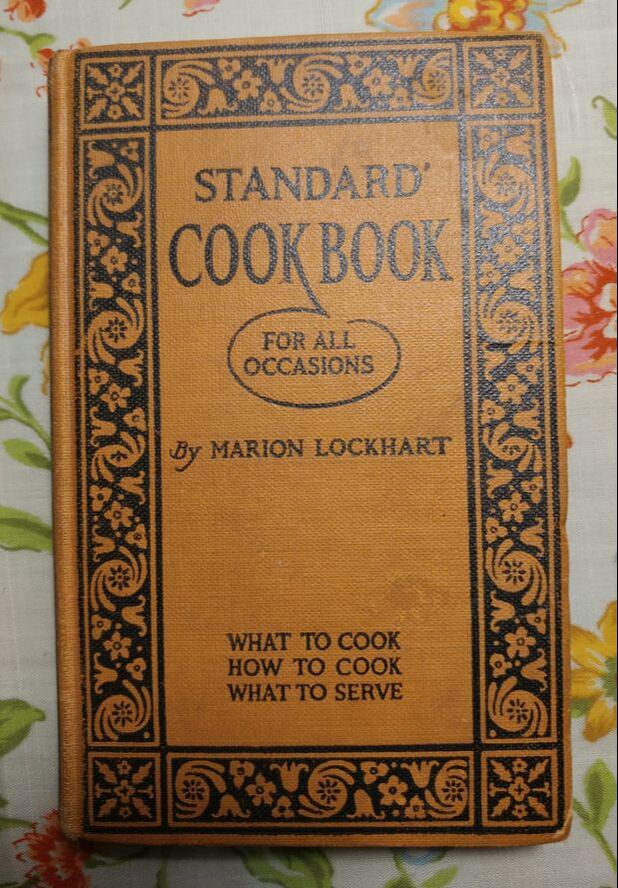

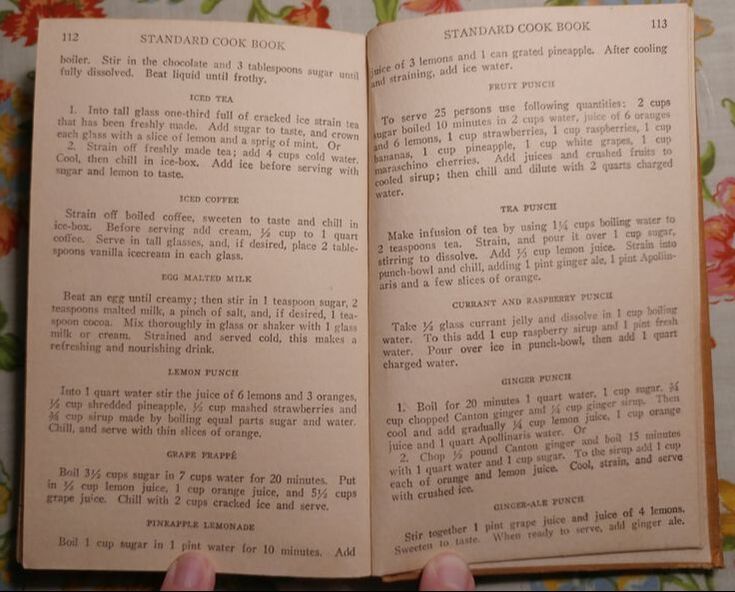

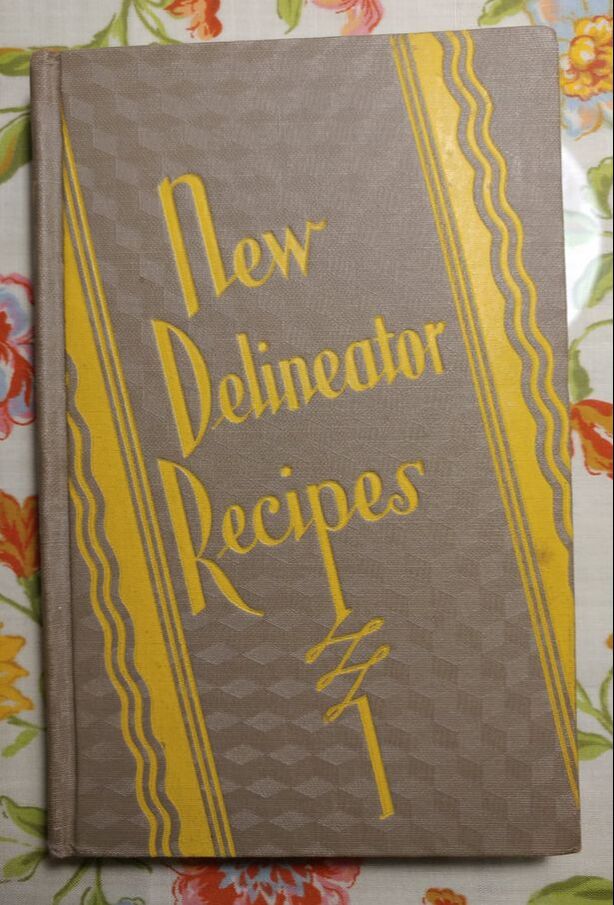

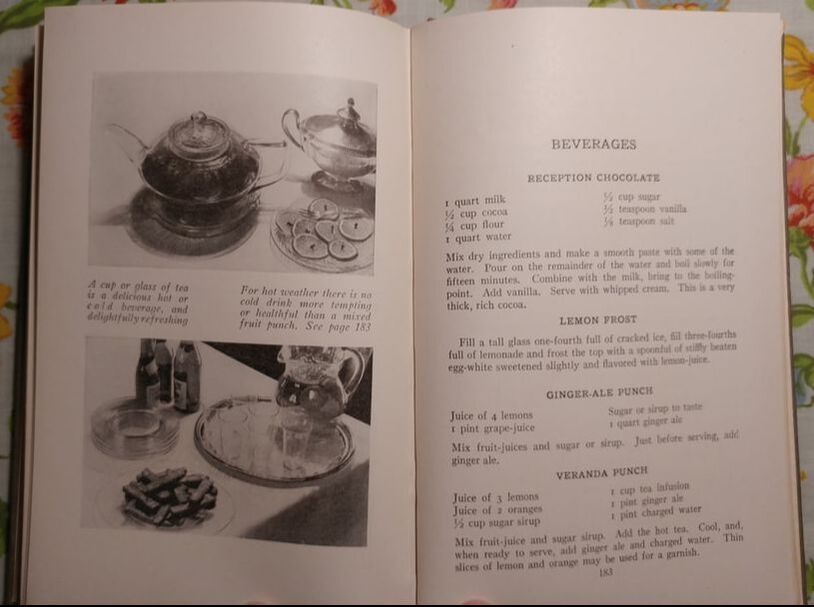

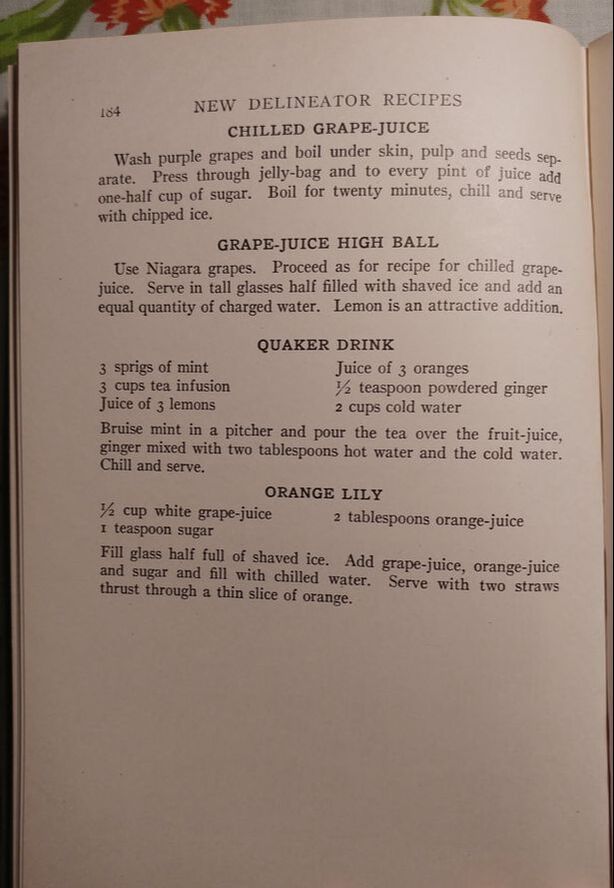

Well, dear readers, it seems as though we are in the '20s again, and since "Dry January" seems to be a growing trend, I thought I would look at some historic alternatives to alcohol for those who don't imbibe or those who are taking a break. Prohibition, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution banning importation, production, sale, and consumption of alcohol in the United States, officially took effect across the country in January, 1920. It was a long, long road to the Constitutional amendment. Begun in the late 18th century, the Temperance movement was a response to the increasing consumption of distilled liquor by the general populace. Rum, distilled by slaves from molasses produced by brutal Caribbean sugar plantations, was flooding the market at the end of the 18th century. Cider, ale, and small beer were common daily beverages. John Adams was known to enjoy hard cider with breakfast. George Washington adored Maderia. All the founding fathers drank at levels that seem excessive by today's standards. And the Whisky Rebellion was just the beginning of American distilling. Alcohol was a way to preserve and consume calories (whether from apples or grain) and was known to be safer for drinking than most water. But it had unsavory unintended consequences. For Temperance advocates, alcohol enhanced all of humanity's sins: drunkenness begat violence, both domestic and public, and wasted hard-earned wages while children starved. In February, 1751, the famed British satirical artist William Hogarth published a pair of etchings in reaction to the Gin Craze. They were meant to be viewed side-by-side, with "Beer Street" at the left and "Gin Lane" at the right. The etchings were accompanied by the following poem: Gin, cursed Fiend, with Fury fraught, Makes human Race a Prey. It enters by a deadly Draught And steals our Life away. Virtue and Truth, driv'n to Despair Its Rage compells to fly, But cherishes with hellish Care Theft, Murder, Perjury. Damned Cup! that on the Vitals preys That liquid Fire contains, Which Madness to the heart conveys, And rolls it thro' the Veins. The pair of images was meant to illustrate the evils of gin consumption in London. In the above image, emaciated drunks line the streets. A drunken woman lets her baby fall to its death. A person has hung themselves in a dilapidated building and other dwellings are falling down. The distillery, pawn shop, and coffin maker are all doing very well and EVERYONE is drinking gin. Meanwhile, on Beer Street, healthily rotund, industrious people are resting from their day's work to have a beer. The pawn broker's building is a dilapidated ruin, the dwellings in good shape as construction begins on another, and everyone is well-dressed and otherwise in good spirits. This images was accompanied by the following poem: Beer, happy Produce of our Isle Can sinewy Strength impart, And wearied with Fatigue and Toil Can cheer each manly Heart. Labour and Art upheld by Thee Successfully advance, We quaff Thy balmy Juice with Glee And Water leave to France. Genius of Health, thy grateful Taste Rivals the Cup of Jove, And warms each English generous Breast With Liberty and Love! If we were to compare 18th century Britain to America, we might replace gin with rum (with its problematic connections to slavery), and beer with hard cider, the drink of choice for thousands of colonists and later American citizens. William Henry Harrison won the 1840 presidential election by running as the "log cabin and cider" candidate - meaning a Western pioneer, the better to appeal to rural voters against the much-maligned Martin Van Buren, of upstate New York, who lost his reelection campaign. But while whiskey, rum, and "fortified" wines like Madeira and port remained popular beverages throughout the 18th and 19th century, alcohol consumption remained as a problem for women and children. Although many Temperance advocates initially just targeted distilled spirits, soon beer and wine and indeed, any alcohol at all, was decried as the root of many evils. Many abolitionists were also Temperance advocates. Lyman Beecher, father to cookbook author Catherine Beecher and her more famous author sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, was an early Temperance advocate. Connected to a religious revival in America as part of the Second Great Awakening, Temperance gained traction in communities throughout the United States. The above image is a 19th century analog to the Hogarth images. At left, a healthy-looking family kneels before a man who is perhaps a minister. The angel of Temperance with her anti-alcohol pledge floats down on a cloud, with cupids and a cornucopia of prosperity. In the background, a new and prosperous looking church At the right, a drunkard, bottle in hand, sprawls on the floor. His overworked wife and starving children huddle in the background, with the little girl praying to the glorious angel. Sad looking shacks appear behind them, with a mob of people in the street. After the Civil War, the fight for Temperance continued. Throughout the 19th century, towns, counties, and even states held referendums on whether or not to go "dry." Some advocates installed drinking fountains in public squares in cities around the country. The Women's Christian Temperance Union, one of the strongest proponents of Temperance, formed in 1874. In 1900, Carrie Nation took to violence, chopping up saloons with a hatchet, to try to suppress alcoholism. In 1913, the federal income tax was instated. For the first time, the federal government had a form of tax income that did NOT come directly from the sale of alcohol, which had previously been the main source of tax income. During WWI, the Temperance movement and the Prohibitionists used the threat of wartime and even the need to conserve grain as a reason to instate Prohibition. Here, the threat of alcoholism and "hardened liver" is compared to the deaths caused by the common house fly. At the bottom, the flyer calls for a Constitutional Amendment. Published in 1917, this flyer was created at the outbreak of World War I. Although the United States was not at war when the above image was published in Puck, it nevertheless made a case to reinstate the Army canteen, where beer and soft drinks were sold. Congress had apparently disbanded them by grace of the Women's Christian Temperance Movement - illustrated here by a hysterical older woman in blue and accompanied by an elderly minister and, in the rear, a "timid legislator." The comparison is made between an Army-sponsored canteen and a public "dive," where soldiers drink to wrack and ruin and can consort with the prostitute implied by her red dress and shoes in the lower right hand corner. This illustrates that some people still fought to keep beer and hard cider as a part of daily life, even as public opinion against distilled spirits waxed to a frenzy. Thirty-six states did, indeed, ratify the 18th Amendment on January 16, 1919. It read, "After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited." Prohibition, as it came to be known, went into effect on January 16, 1920. Prohibition came to represent government overreach into peoples' daily lives and the criminalization of alcohol allowed organized crime to flourish in the 1920s, despite the best efforts of police. Gangsters like the infamous Al Capone, wielding machine guns they learned to use in the First World War, made fortunes off of illegal distilleries, speakeasies, and other criminal enterprises, all while dodging federal taxes. Well, at least until the Feds catch up with you, right Al? The wealthy could afford to keep consuming booze (often from the wine cellars amassed on their private estates) as police and prosecutors largely looked the other way. The poor and middle class risked their lives on bathtub gin, wood alcohol, and methylated spirits (also known as denatured alcohol) which caused blindness or even death. The illegality meant that alcohol production was unregulated and therefore dangerous to human health. Prohibition was ultimately a failure. The stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression left many people in severe economic (and mental) distress. It was repealed on December 5, 1933, with the ratification of the 21st Amendment, which specifically repealed the 18th. For many, the return of the ability to self-medicate with alcohol helped temper the despair of the Depression, although it likely ruined as many lives as it helped. But while romanticized notions of the "Roaring Twenties" continue today, we can learn from the problems that Temperance sought to solve. Absenteeism and incarceration both declined during Prohibition. Alcohol consumption overall did decline in the 20th century, thanks in large part to the Temperance movement. Today, more and more people are reassessing their relationship with alcohol. In 2006, food writer John Ore coined the term "Drynuary" to describe what he and his wife considered to be a post-holiday alcohol detox. "Drynuary" or "Dry January" has been embraced by an increasing number of people and while the peer pressure to consume alcohol in social settings still exists, it is becoming more acceptable to abstain in public. Are we on the brink of a new Temperance movement? Probably not, but interesting to see the historical parallels. As we are in full swing of "Dry January," and as more people are embracing temperance, we can look to the past for interesting non-alcoholic beverages to tempt our palates. The nice thing about having an extensive library is that it is easy to do research when I want to - I just head upstairs to my little office and library, tucked up under the eaves of our little house. I pulled a couple of 1920s cookbooks that revealed some fascinating recipes. Coffee and tea were the most common alcohol replacers in polite society, but a number of fruit-based beverages and punches were also popular. Of course, most of them are very heavy on the sugar. The rise of soda fountains in the 1900s was in part a direct response to Temperance - it was a wholesome place for young people, women, and families to meet and socialize. It also meant that many Americans were replacing the vice of alcohol with what we know today to be the vice of sugar. Good Housekeeping Book of Menus, Recipes, and Household Discoveries (1922)The first book I perused was not this one, but I thought I would start here because it is the oldest of the 1920s cookbooks I looked at and its recipes were among the most interesting. Good Housekeeping's Book of Menus, Recipes, and Household Discoveries was published in 1922. Don't these sound delightful? "Apple Tree Dulcet" in particular is a brilliant name, although it's much more of a dessert than a beverage. "Gingerade," made with fresh or "green" ginger root also sounds delightful, if spicy. Grapefruit PunchOf these I think the Grapefruit Punch sounded the most delicious. I love both grapefruit and maraschino cherries, but have never had them together. I often drink half grapefruit juice, half ginger ale as a bitter-sweet winter tonic. 2 cupfuls water 3/4 cupful sugar 1 cupful grapefruit juice 1/2 cupful grapefruit pulp juice of 1 lemon 1/4 cupful maraschino cherries mineral water Combine the water and sugar, boil one minute, and let cool. Meanwhile, extract the grapefruit juice and to this add the grapefruit pulp and the lemon-juice. Allow to chill thoroughly and then add the maraschino cherries cut in halves. Dilute with mineral ice-water and serve very cold. Westminster Church (Utica, NY) Cook Book (1924)I love collecting community cookbooks - the earlier the better. This particularly nice one from Utica, NY (which is also where I found it), has just one page of beverages. Published in 1924, it includes a homemade version of what was likely a soda fountain drink: Strawberry Flip. Note that it calls for only one TABLESPOON of vanilla ice cream. Per serving, of course. The one that seems the most interesting to me is the first Fruit Punch, by Bessie C.B. Capron. Fruit Punch1 cup sugar 1 cup very strong tea (black) 2/3 cup orange juice 1/3 cup lemon juice 1 pint ginger ale 1 pint appolinaris This makes enough for 10 glasses. Okay, this probably needs a little translation for most people. To make the tea very strong, steep 2-3 bags in one cup of boiling water. The orange and lemon juice should be fresh-squeezed. And the ginger ale is probably better if you can find something a little stronger than your garden variety - a craft ginger ale would do nicely. And appolinaris? That's a German type of sparkling mineral water. Known as the "Queen of Table Waters," Appolinaris was a brand name mineral water discovered in the 1850s that is still around today. Although these days it's owned by Coca-Cola. This recipe is actually somewhat similar to 18th century punches that called for sugar, citrus juices, black tea, and sparkling water, albeit with the addition of strong spirits like rum and brandy (see: Fish House Punch). Standard Cookbook - For All Occasions (1925)Marion Lockhart's Standard Cookbook is a teensy tiny little hard cover (hence the fingers to hold it open). Published in 1925, it has a wide variety of punches, which is lovely. I do love malted milk, but I'm wary of raw eggs, so the "Egg Malted Milk" is not one I would probably attempt. However, the "Currant and Raspberry Punch" sounds divine. Currant and Raspberry PunchTake 1/2 glass (about 3-4 ounces) currant jelly and dissolve in 1 cup boiling water. To this add 1 cup raspberry sirup and 1 pint fresh water. Pour over ice in punch-bowl, then add 1 quart charged (sparkling) water. This makes about 2 quarts and seems like the perfect pink party punch to serve for Valentine's Day or a girly party. Despite the syrup and jelly, it also probably isn't too sweet, as you're cutting about 1 pint of sweet stuff with 1 pint of water and a quart of sparkling water. New Delineator Recipes (1929)And last but not least! The New Delineator Recipes. Published in 1929, this one comes with a few quite lovely photos. "Reception Chocolate" looks delicious and would be perfect for a winter hygge party. "Veranda Punch" listed here is very similar to the "Fruit Punch" listed above. Of all of these recipes, "Grape High Ball" sounds the most interesting, in part because it uses Niagara grapes. If you live in the Northeast, you can still find both Concord and Niagara grapes at some U-Pick orchards. If you've never had Niagara grapes, I recommend trying them if you see them. A dusky golden color, neither they nor the classic deep purple Concords are much like today's table grapes. Niagara grapes are very soft, with slippery-sweet insides and seeds. But they have a lovely flavor - almost perfumed, and would make a sophisticated beverage. Niagara Grape High BallFor sake of ease, I am combining the two recipe instructions. Wash grapes and boil [until] skin, pulp, and seeds separate. Press through a jelly bag and to every pint of juice add one-half cup of sugar. Boil for twenty minutes and chill. In glasses half-filled with shaved ice, add equal parts syrup and charged (sparkling) water. Lemon is an attractive addition. Well, that's all for now folks. Are any of you attempting a Dry January? If so, what do you normally drink for festive occasions? Share in the comments!

And, as always, if you enjoyed this (long!) post, please consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today! And what a year it has been! But Sarah, you say, a year? Didn't "The Food That Built America" only come out in August? Why yes, dear reader, it did. But the magic of television isn't created overnight. And it was exactly on January 16, 2019 that the dear folks hired by the History Channel to do the production of that wonderful series sent me an email through this very website. Although I have been on television before, this was my first interview of this length and professionalism. It took place on a frigid January day in a Brooklyn warehouse equipped with a very noisy heater. So it was off during filming. My 2 pm interview was constantly interrupted by the air brakes and backing-up beeps of the trucks that still visited the industrial area where we were filming. At one point you could see my breath on the air. But dear reader, it was so FUN. There were two cameras, one on a track to my side, which was a bit intimidating. The other was affixed with a mirror so I could see interviewer Thaddeus in the reflection (he was sitting to the side of the camera) and look right into the camera while appearing to look him in the face. Which made things much easier and less intimidating, to be honest. There were also about 10 people in the room with us, but of course they were so quiet it was easy to forget they were there. Thaddeus asked me lots of interesting questions, and I did my best to give good answers and, my specialty, lots of fantastic context to all the topics they were discussing. On several occasions, I even managed to repeat myself after each truck interruption without losing too much of the original quote. In all, I'm pretty proud of how I acquitted myself. My only regret is the World War I context - Thaddeus didn't make it clear in his questioning that they were going to be talking primarily about the businesses during WWI, so my responses were all about the regulations on individual Americans. Had I realized, I could have pontificated at length about the impacts on food businesses and retail during the war. Oh well. No one's perfect. At any rate, a friend who teaches Family and Consumer Science (or FACS, as it is often called) told me the other day that FACS teachers around the country were using "The Food That Built America" in their lesson plans. And every couple of months another person I went to high school with or I know through work takes the time to mention that they saw me on TV, which is always fun. Although, sadly, I did not receive payment for my interview (as I'm sure few of the other interviewees did), I did get a free train ride and a car to pick me up, so that was nice. If you haven't seen "The Food That Built America" yet and you have cable - check out the History Channel from time to time - they seem to be replaying it quite frequently. Looks like they removed the online screening from The History Channel website, sadly. BUT! If, like me, you do NOT have cable, you can purchase or rent the episodes through Amazon Prime. As an Amazon affiliate, if you purchase anything from this link, I will get a small commission. Have you seen "The Food That Built America?" What was your favorite part? If you saw and enjoyed "The Food That Built America," please consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

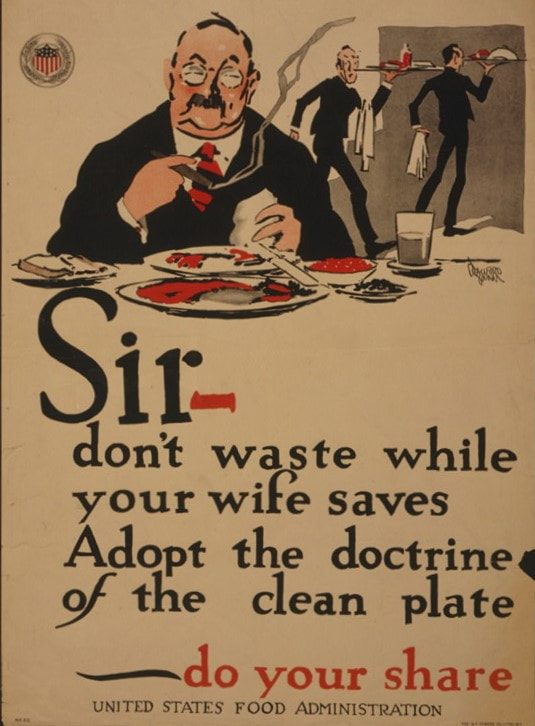

January is the time of year when many Americans, having made New Year's resolutions, try to eat healthier. But household food waste accounts for a good chunk of overall food waste, which besides being a big waste of water and energy, is also a contributor to the production of greenhouse gases. During both World Wars, food waste came up, but the First World War was a bit more significant. We were still coming off the effects of the Gilded Age, when wealthy Americans ate to excess, feasting on a great deal of meat, including some from rare or even endangered animals (for instance, terrapin, the diamondback turtle made so famous by soup, was hunted nearly to extinction and is still threatened to this day). Even as we underwent a series of depressions and industrial recessions between 1893 and 1914, the rise of restaurants and the proliferation of refrigerated railroad cars made more food accessible to more Americans than ever before. But WWI made global competition for resources more intense than ever. As the United States entered 1917 with only enough wheat to feed itself, and hog, beef, and dairy production designed largely for domestic consumption, Americans had to conserve in order to free up enough food to send overseas. The United States Food Administration's anti-waste campaign was part of that conservation plan. Progressives loved statistics, and used them to good measure. If each American saved just one slice of bread per meal, for instance, it would add up to hundreds of thousands of loaves, which would translate into plenty of wheat flour to be sent overseas. Combined with messages of thrift (curbing waste saves money) were subtle messages about weight and consumption that fit in nicely with the new Progressive values of self-control, an active lifestyle, and the willowy Gibson Girl physique. This propaganda poster is a good example of just that. A rather large man, reminiscent certainly of the rotund gentlemen commonly seen in Gilded Age paintings and photographs, sits alone at a table, smoking a cigar. Clearly he has finished eating, although there is still food on all of the numerous plates in front of him, and two waiters in the background bear away trays containing more half-eaten food. One of the slender waiters looks back incredulously at the diner. The text says, "Sir, don't waste while your wife saves. Adopt the doctrine of the clean plate - do your share." Restaurants in particular would come under the jurisdiction of the United States Food Administration, but while there were restrictions on bread service and sugar bowls and meat on the menu, the federal government could not stop people from ordering as much food as they could afford, whether they ate it or not. The reference to the wife was perhaps meant to shame men. Women were largely in control of the household meals, and many middle and upper-class women were taking to voluntary rationing with a vengeance. Perhaps wealthy men escaped to restaurants to eat as they pleased. The federal government was urging them not to undo the patriotic war work of their wives and to pull their own weight in the fight for food conservation. The first propaganda poster makes a slightly more subtle play, reading in part, "Leave a clean dinner plate. Take only such food as you will eat. Thousands are starving in Europe." Sound familiar? Perhaps your family used the (admittedly racist) "Children are starving in Africa," but the sentiment is the same. Photographs and images of children in Belgium and France were being used to good effect in the United States in an attempt to wake up isolationists to the terrors happening abroad. Both phrases use guilt and shame to get you to finish eating everything you took. Not exactly the most healthful advice, but at least during WWI they recommended you take only what you knew you could eat, instead of letting your eyes be bigger than your stomach. Although not as popular as calls to plant war gardens or can fruits and vegetables, the "gospel of the clean plate" nevertheless urged people to think more about food waste. Of course, as one woman complained in a letter to Herbert Hoover, the poor already saved food, planted gardens, ate less meat, and preserved what they could. Still it's advice that we would all do well to emulate today. We're pretty good at eating leftovers in my house, but sometimes we just can't finish them in time or (shocker, I know), dinner wasn't as good as you'd hoped, so eating the leftovers becomes a real chore. My leftovers usually make it to the compost pile, if not our stomachs. But other food waste reduction advice of the time included feeding But if you find yourself buying boxes or bags of leafy greens and salmon and fresh fruit in a fit of health this year, maybe hold off a bit, and eat down your cupboards instead. If you enjoyed this edition of World War Wednesday, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

Longtime followers of this blog may have noticed that I keep moving the goalposts on book publication. That's because life, as it often does, has intervened in the past few years. So poor "Preserve or Perish" gets neglected, and I feel guilty about it. I'm hoping that 2020 will bring more stability, less stress, and more routine and free time. So of course, the book is at the top of the list! My primary goals for 2020 are thus: Write.My book, "Preserve or Perish," on food in New York State during WWI is nearly complete. Peer reviewers wanted more context, my editor wanted a chapter on propaganda, and I wanted to add recipes and make the academic text a little more approachable to the lay reader. But editing, an essential part of the writing process, is HARD. Especially when adding context means you have to go back and read (and take notes on) and condense and cite even more secondary source books. I am, however, probably most of the way there. I'm not sure what the final book will look like, as this one is ending up longer than expected, but I know that the finished product will be better for the time and attention. Setting a completion deadline for myself also usually works to kick in my "oh no I have a deadline let me work furiously and extremely efficiently to meet it" generally works. So fingers crossed. I also want to post more in this blog. Thank goodness for the scheduling function, so I can sit down and write a few posts at a time. But I also want to branch out in topics. I've loved the World War Wednesday series, but I want more time for historic recipes and cookbooks, too. Teach.I know a LOT about food history. I've been studying it, on a fairly regular basis, for over 15 years. And I want to share what I know, but the traditional college course is not really for me (also, adjuncts are treated terribly in academia). Which is why I'm in the process of developing a couple of online courses. I also want to get back into podcasting and/or make a few YouTube videos. Part of the online course process is creating online videos, so why not make a few shorts to post on YouTube? Organize.In the past few years I've acquired a LOT of vintage cookbooks. I've managed to organize some of them, but I have it on good authority that more are coming in 2020. So, that not only means organizing my library (again), but also cataloging what I have and digitizing a few gems to share. Community.This is a bonus resolution, in part because I think it will be so much fun. We've got a great group over on Facebook and my Patreon patrons delight me in more ways than I can say. But I'd like to develop a place for all us like-minded folks to be able to better communicate and spend time together. SO! To that end, I'd like your feedback! What do you think of these goals? I've made a little survey for you to take (only 4 questions long!) and help shape the future of The Food Historian. How About You?Do you have any 2020 goals related to food, history, or food history? Share in the comments!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed