|

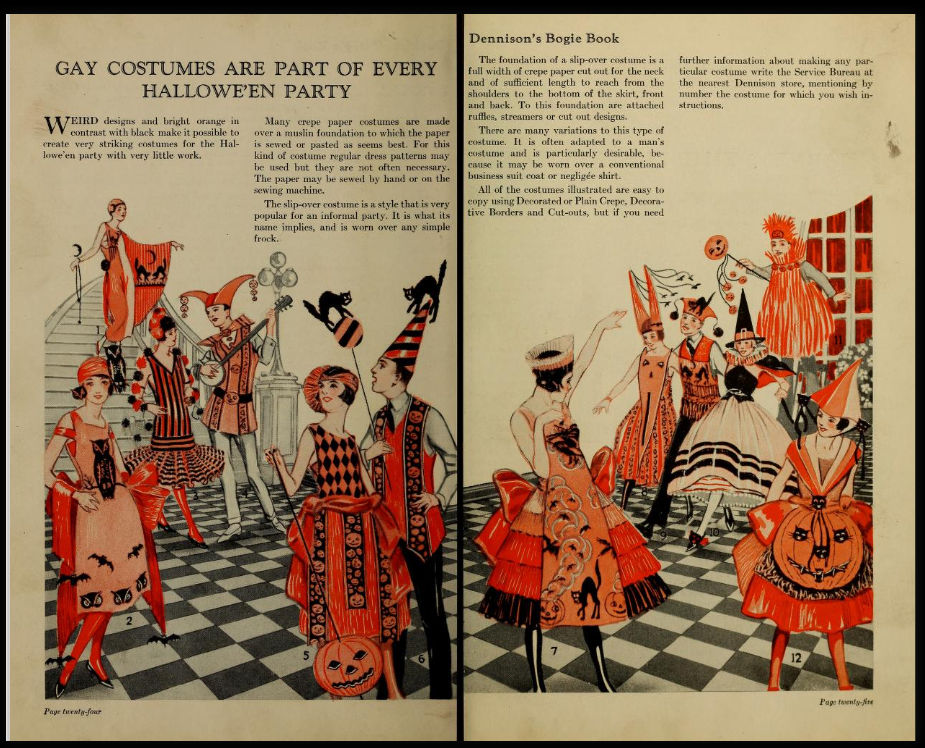

Halloween is a distinctly American holiday. Although it may have its roots in Great Britain, lots of wonderful traditions started right here in the U.S. In particular, Halloween parties became very popular in the 1920s, helped in part by the work of a crepe paper company called the Dennison Manufacturing Company. Starting in the 1920s they published a series of "Bogie Books," which were part advertisement, part instruction manual on how to use their products to craft your own Halloween decorations, costumes, and party favors to throw the perfect party. Few Bogie books have been digitized, as they are insanely popular collector's items, as are the paper goods the Dennison company produced. However, via the Library of Congress, the Internet Archive has a digitized copy you can peruse! Chock full of fantastic images like this one: There are other Halloween party-planning gems out there as well. Mary Blain's "Games for Hallow-e'en" from 1912 is lovely for party ideas, with lots of historic divination games perfect for this time of year. Halloween is one of my favorite holidays. I love to decorate, dress up, and feed people. So it's no surprise that throwing a vintage-inspired Halloween part was right up my alley. When I said I wanted to dress up as a spiritualist medium, a friend suggested making the whole party 1920s and '30s themed! So I did. Costumes in the theme were required and some folks really outdid themselves. Sadly (or perhaps, wonderfully), most of my guests are usually so busy chatting and eating and having a good time, that we never have the chance to do games or activities! I did take some inspiration from the Bogie Books, however, as paper decorations definitely played a leading role. Halloween parties in the early 20th century might have had elaborate decorations and games, but the food usually hearkened back to simpler times. Very seasonal, the suggestions usually included nuts, apples, pumpkins, corn, and other autumnal foods. Gingerbread, popcorn, and apples - fresh, roasted, or as dumplings - evoked the Colonial era. Sweets, including candied apples, popcorn balls, cookies, fudge, and other candies were often homemade, although plenty of store-bought confections were certainly available. Halloween parties were usually the purview of the young, so food was teenager-friendly and included sandwiches, pickles, and many of the aforementioned treats. Simple was considered best. With that in mind, and channeling an early 20th century home economist, I made sure all the food was color themed in orange, white, and black! And because I had a lot of events and late work nights leading up to the night of the party, I tried to simplify things to help-yourself snacks. We had:

The smash hit of the evening was blue cheese dip with sweet potato chips. And everyone, even people who claimed not to like bread pudding, loved my bread pudding. Because I make the best. :D It was a bit of a scramble, but I was able to get all the fruit and veggies chopped and all the dips made (with a few exceptions) in like, two hours. Three, if you include the time to make and bake the bread pudding. Stay tuned for more recipes, but here are two: the easy-peasy blue cheese dip (seen here in the cute white pumpkin baking dish), and the roasted garlic white bean dip. Hot Blue Cheese DipNo messy combining mixing cold cream cheese with this one. Just heat, stir, and serve! 3 packages (16 oz.) neufchatel cream cheese 2 packages (8 oz.) Castelano or other very soft creamy blue cheese (or gorgonzola dolce) about a handful shredded mozzarella cheese Place blocks of cream cheese, blue cheese, and mozzarella in an oven proof dish. Bake at 350 F, uncovered, until cheese is soft and melty. Stir thoroughly to combine. Serve hot or room temp with plenty of sweet potato chips. Roasted Garlic White Bean DipFull disclosure: I tried to "roast" garlic cloves overnight in the crock pot and it mostly did NOT work. Even on low. But no time called for desperate measures. Cloves got hard/almost burnt. Worked well enough for the dip, though. I just fished the crunchy ones out before sending through the food chopper. I would recommend making roasted garlic in the oven or using whole heads of garlic instead. This also makes a LOT. So feel free to cut the recipe in half if you're not feeding a crowd. 2-4 heads of garlic, roasted and removed from skins 2 double cans cannellini beans, drained olive oil Process the beans and roasted garlic in stages with the olive oil until smooth. Add to crockpot and keep warm. Serve warm or room temperature with blue corn chips or pita chips. If you wanted to spice things up a bit, some dried thyme or fresh basil or parsley (or all three!) would not be remiss. If you want more party ideas, recipes, and other vintage food fun, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon! Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

0 Comments

Okay, so this is only peripherally about food, but it's an important image to give some context about. During both World War I and World War II, gasoline was in short supply. It and rubber tires were actually rationed during the Second World War, as evidenced by the propaganda poster above. In it, a woman walks along, her arms full of packages. In the background, the silhouettes of soldiers, bayonets fixed, packs full, march behind her. She says, "I'll carry mine, too!" making a clear reference to the packs the soldiers behind her are carrying. Below it says, "Trucks and tires must last till victory." This image needs some context because most modern Americans don't realize what grocery shopping was like before the 1950s. As a rule, most cities did not have supermarkets as we know them today. That development was starting in the 1940s, but it was not until the end of the war that being able to roam a large store with a shopping cart and help yourself was a common occurrence for most ordinary Americans. Most Americans in the first half of the 20th century visited individual shops - a greengrocer for produce, a butcher for meat, a bakery for bread and pastries, and often yet another store for canned goods or staples like flour, sugar, and coffee. In big cities, you might also visit a cheesemonger, pickle store, or other specialty shop. Milk and other dairy products were obtained from a fluid milk dealer, who delivered. Although early in the century lower-quality milk was sometimes also available "dipped," meaning you brought your own pail and they dipped it out for you. This was largely consumed by folks who could not afford to have higher quality bottled milk delivered. But many families also had other food products delivered. It made sense prior to the First World War. After all, milk, ice (for your ice box), and coal were already delivered. It was simple enough to use a telephone to place a weekly or even daily order from the butcher and greengrocer. But wartime meant efficiencies. So delivering small items to individual households multiple times a week was a waste of manpower and fuel. The campaign to cut down on deliveries started during the First World War as housewives were encouraged to actually visit the stores they ordered from. Propaganda persuaded housewives that they could better keep an eye on quality and sanitation if they went themselves. Which was likely true, as some housewives may have been duped by unscrupulous shopkeepers. But housewives visiting those shops themselves would have still had to place a request with a shop clerk, who would retrieve the items and weigh or measure them for you from bulk. With the exception of the increasing popularity of brand name products, many people still bought "generic" bulk goods. Gelatin, coffee, canned soups, boxed cereals, crackers and cookies, condiments like ketchup and mustard, spices, and coffee and tea were increasingly purchased pre-packaged. But someone else brought the package down from the shelf for you. That way of shopping was changing by the 1940s, but home deliveries still abounded. During World War II, the emphasis was on saving fuel and tires. By walking and carrying her own goods, the housewife was saving on fuel, rubber, and manpower, too. Of course, changes to housing patterns post-war would also play a role. The development of suburbs meant that no longer could the housewife walk or take public transportation to the nearest store. She had to drive. Driving meant she could carry more, and bigger refrigerators and new deep freezers meant she could shop less frequently, too. It was a sea change in how life was lived. And the repercussions are what many people are trying to escape today, with a return to mixed-use and walkable neighborhoods. Despite living only a mile or so away from several grocery stores, there are no sidewalks in my neighborhood and I live on a very busy road where the speed limit is 55 mph. Which means I have to drive to stay safe. But I try to combine trips on my way home from work to be more efficient. In this day and age, communities are also increasingly banning or restricting the use of plastic bags. The county I work in has a total ban, and charges 5 cents for paper bags. As a result, I've started carrying reusable bags with me more often. But the lack of plastic packaging in this image is striking - the boxes are wrapped in brown paper and tied with string. In her paper bag, a bunch of carrots with green tops pokes out of top, along with what appears to be celery and paperboard boxes - maybe pasta or cereal? At any rate, it's a striking image, and one with some lessons in sustainability. Could we ever go back to an era of paper, cardboard, tin, and glass when we are currently so addicted to single-use plastic? Something to think about. How do you do your shopping? If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more!

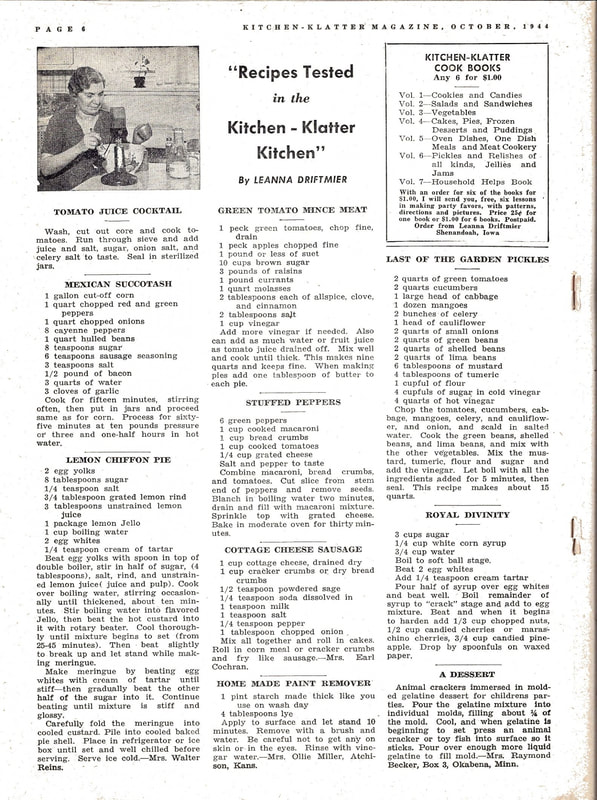

Inspired by my Patreon patrons (please join us!), I'll be occasionally posting Meatless Monday historic recipes. I ran across a gem of a website with scanned pages of all the recipes from Kitchen Klatter Magazine. The magazine was an outcropping of a radio show by the same name, hosted by Iowa homemaker Leanna Field Driftmier. On the air for sixty-one years, Kitchen Klatter is thought to be the longest-running show of its kind in the U.S. Anyone interested in doing some research on Driftmier can find her papers as well as cookbooks and other materials at the University of Iowa Library. I have an interest in homemaker radio shows, but my World War I research isn't quite ready to let go of me just yet, so more in-depth research is on the horizon. Sadly, it doesn't seem as though the Kitchen Klatter radio program survived, although I could be wrong. Few, if any of them, have been digitized. Although oral history collections and historic film are often preserved through digitization, historic radio is more neglected, particularly homemaker shows. At any rate, this particular recipe page (listed above) is from 1944, toward the end of the Second World War. In my opinion, cottage cheese is completely under appreciated in modern American cooking, which is why I always enjoy finding historic recipes for it. High in protein and generally low in fat, it is creamy and delicious. Cottage cheese, and its siblings ricotta and farmer cheese, are well-used in many European cuisines, particularly in Eastern Europe. RECIPE: Cottage Cheese Sausage1 cup cottage cheese, drained dry Note that the recipe calls for "cottage cheese, drained dry." Cottage cheese naturally has creamy whey in it, but for this recipe you need to drain the whey off or use farmer cheese, which is simply cottage cheese that already has the whey drained off. To drain, line a sieve with cheesecloth or a coffee filter, place it in a bowl to catch the whey, and add the cottage cheese. Cover and refrigerate for several hours or overnight. Before using, squeeze out any additional whey. Frying "sausages" like this will require a fair amount of oil - preheat a pan (I prefer a cast iron skillet) and cover the bottom with enough oil to run when the pan is tipped. Or, add even more to shallow fat fry the sausages. Serve with mashed or roasted root vegetables and a green vegetable, or, for a more breakfast sausage treatment, serve with pancakes, french toast, or fried eggs. BONUS RECIPE: White Bean "Sausage" CakesAs a bonus for the vegans out there, I made up a similar recipe last year using canned cannellini beans and oatmeal. Here's an approximation of the recipe (I make it differently every time). 1 can cannellini beans, drained (save the liquid) There are lots of "mock sausage" recipes that have been around since very early in American history. The sage is the primary suggestion of sausage, so don't leave it out, unless you prefer herbed white bean cakes to mock sausage. Now that the colder weather is back with us, I think I may just attempt the cottage cheese recipe. Do you have any historic vegetarian recipes to share? What have you been cooking lately? If you enjoyed this installment of #MeatlessMondays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more!

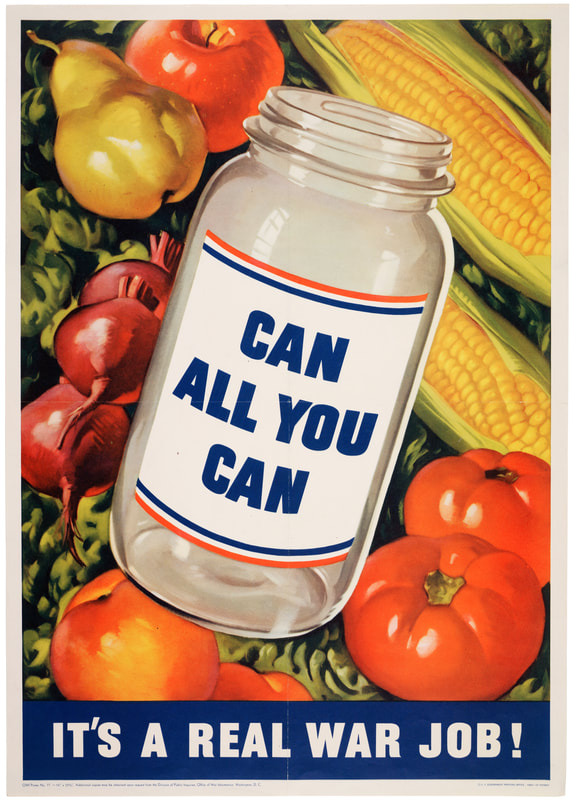

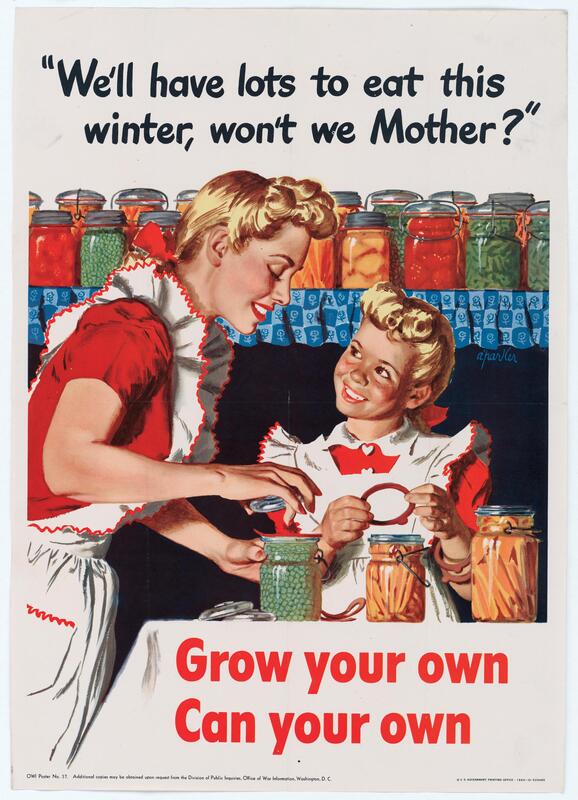

Remember last week's foray into home canning during the First World War? Victory garden and canning efforts returned for World War II. Unlike the First World War, rationing during the Second World War was mandatory and regulated by the Federal government. Because purchased foods were restricted, Americans were strongly encouraged to keep victory gardens. And because commercially canned goods were needed for shipment overseas, ordinary people were encouraged to preserve the fruits of their victory gardens at home. Propaganda posters like the one above made great efforts to frame the drudgery of home food preservation in wartime terms. Housewives were encouraged to "can all you can," while the poster cheerily chirped, "It's a real war job!" presumably to put the kibosh on all the naysayers who insisted otherwise. In addition to being a "real war job," canning efforts were framed in a number of ways. In the above poster, a proud housewife, with perfect victory curls, a ruffly floral apron, and an armful of jars (beets, green beans, and tomatoes from the looks of it, with more beets, raspberries, and corn below) indicates that not only is she preserving food for her own family, she's also "fighting famine." By "canning food at home," she's freeing up commercially canned goods to be sent overseas to help the civilians of war-torn countries stave off famine. In this final poster, a cherubic little girl, in a dress and frilly apron that matches her mother's outfit, helps place the rubber rings on wire bail jars of carrots and peas, preparing them for canning. Hopefully in a pressure canner, since low-acid vegetables like peas and carrots need to be canned at higher than 212 degrees Fahrenheit (boiling point) in order to be safe from botulism. The girl says, "We'll have lots to eat this winter, won't we Mother?" implying that a well-stocked home pantry like the one in the background provided security against future food shortages or tightened rations. Both the promotion of home canning and the implementation of wartime rationing reflected an agricultural system not designed to provide massive surpluses. Coming out of the Dust Bowl era of the Great Depression, agricultural practices in the United States had improved, but most of the food produced at home was still consumed at home. Cuts had to be made domestically in order to free up the food supply for shipment overseas. In the decades since the Second World War, American agriculture has been transformed, both by the leftovers of chemical warfare and explosives production (pesticides and chemical fertilizers come to mind) but also by the mindset that producing unlimited food brings global security. Improvements to global shipping have meant that it is now as easy (or easier, and certainly cheaper) to get garlic from China as it is from the farmer down the street. Or apples from New Zealand or Peru than from a local orchard. Home preservation and home kitchen gardens are certainly no longer necessary, given the world of food at our fingertips at both grocery stores and online. With home food preservation no longer necessary, canning and gardening have taken on a sheen of delight. For many people, it is preferable to can your own jam from berries you picked yourself, rather than buy from the store. But I think the romance that hangs around home food preservation today belies the struggles of the past - when poorly preserved foods or inadequate supplies meant illness and hunger. When a poor harvest didn't just mean higher prices at the grocery store, but threatened real starvation. it's important to remember that food preservation during World War II played an important role in both nutrition and improving the everyday diet of Americans. But it's also important to recognize the amount of labor spent on both victory gardens and home canning at a time when American labor was already stretched thin in the war effort as factories ramped up production and speed, women took on the work of fighting men, and everyone hustled to get things done with fewer people and fewer resources. The size of the United States meant that we never quite had the same threats of deprivation as the U.K., which is perhaps why they are so much better at telling their WWII home front stories than Americans are. The size and scope of our continent meant we could be self-sustaining and still provide food abroad, whereas the United Kingdom had to learn how to do without regular food shipments to its tiny island. So the next time you do some home canning, whether from necessity or for fun, I hope you remember the people of the past. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed