|

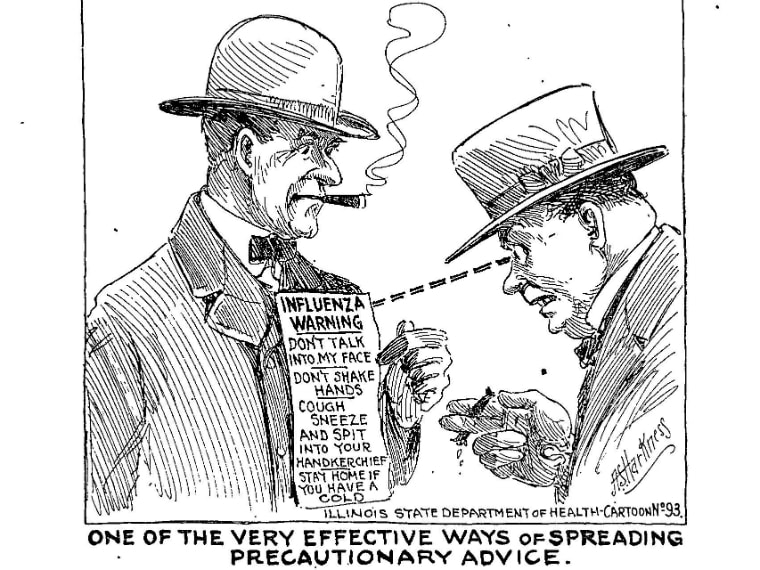

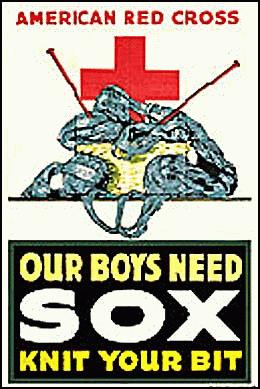

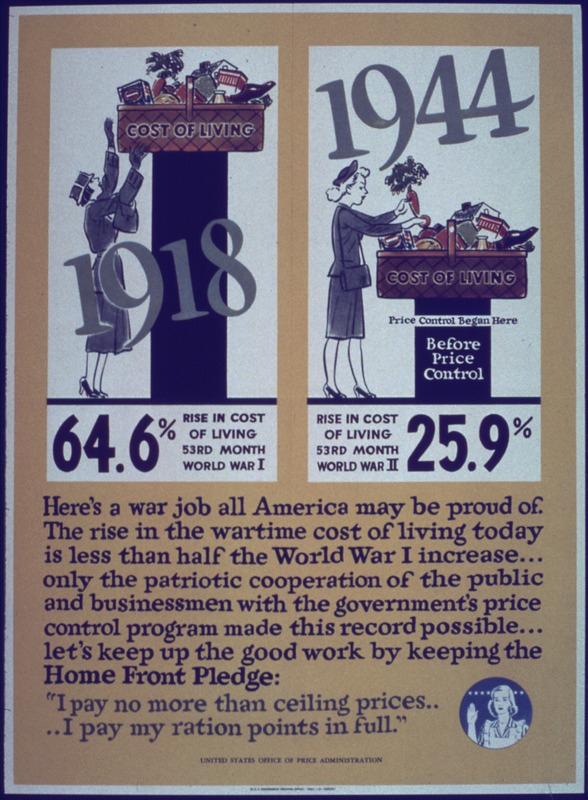

Y'know that old saw, "Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it?" Well, like a lot of old adages, this one has a big grain of truth in it. Historians often can see parallels to the modern world as they study history. Indeed, my area of specialty - the Progressive Era and World War I home front - has led to LOTS of comparisons to modern life. But with the addition of the coronavirus lockdown, the comparisons grew more numerous. To that end, I thought I would catalog some of the striking similarities. Failure of Bureaucracy: Military SupplyOne thing that has becomes especially striking at this time is the failure of the federal government to manage national supplies during an emergency. In this instance, it's the management of medical supplies for COVID-19, particularly personal protective equipment (a.k.a. PPE). States are competing on an open market and with each other, driving up prices and leading to shortages. To make up the shortfall, ordinary citizens are creating homemade versions of masks, face shields, and other equipment. During the first months of the U.S. entrance into World War I, the exact same thing was happening. Historian Robert Ziegler in his book America's Great War: World War I and the American Experience, outlines the deplorable state of military supply following the Spanish American War. Individual battalions were competing with each other on the open market to purchase supplies, thus driving prices up. In addition, the United States had never fielded such an enormous army and the production of other military supplies, such as uniforms and rifles had yet to keep up with the demand of a suddenly-enormous army. According to historian David M. Kennedy, in his book Over Here: The First World War and American Society, soldiers were sent to Europe with hardly any training. Men and boys who had been recruited in July, 1918 were on the front lines by September. Some men arrived never having used a rifle, and had to take an intensive 10 day course before being sent into battle. The logistics of shipping war materiel, both within the borders of the United States and overseas was also a mess, causing railroad and port backups. Some credit the poor supply of soldiers in training camps (inadequate clothing, bedding, housing) with exacerbating the effects of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Combined with this was the efforts of the American Red Cross. Famed for providing bandages and nursing aid during the American Civil War, thousands of chapters sprang up across the nation and throughout 1917, women were encouraged to "knit their bit" by knitting sweaters, socks, wristers, and watch caps for "our boys" being sent overseas. Why? Likely because military supply chains were, as stated, in shambles and because it was easier (and cheaper) to task the nation's women with keeping soldiers warm than to mobilize factories. Wool socks in particular were in high demand because of the poor conditions in the trenches. But by 1918, according to historian Christopher Cappazola in his book, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, the federal government was frantically telling women to STOP knitting, likely because military supply was completely reorganized. Although there are plenty of resources about knitting in WWI and the American Red Cross (including this lovely one), few people seem to have made the connection between "knitting your bit" and the failure of military supply. It was only part-way through American participation in the war that the federal government reorganized military supply under a centralized Quartermaster General. It wasn't until the Korean War that the United States passed the Defense Production Act (1950), which empowered the federal government to compel private business to prioritize the production of war materiel and prevent hoarding and price gouging. If the United States were to learn the lesson of WWI supply today - the federal government would coordinate with individual states to purchase - and allocate - medical supplies where most needed, instead of bidding against states on the open market. Xenophobia, Immigration, RaceIn the years leading up to the First World War, the United States was inundated with immigrants from all over the world, but particularly Eastern and Southern Europe. The United States was also recovering from the abandonment of Reconstruction and Black Americans were becoming more and more prosperous, with a growing middle class. Combined with a brain and labor drain on rural areas, this led to people like President Theodore Roosevelt warning of "race suicide" for White Anglo Americans unable to keep pace with the more fertile immigrants. Roosevelt also worried about rural life and started the Country Life Commission to study and combat the drain of population from rural America to urban areas. Tempted by "cosmopolitan" life, reformers worried, young people would be corrupted and the bedrock foundation of democracy - the landowning yeoman farmer - would diminish. Unfortunately for reformers, the majority of people in rural areas lived difficult lives and particularly in the South, most did not own the land they farmed. But the idea that rural America, and farmers in particular, are the "salt of the earth" is an idea that has persisted even today. With "flyover country" being courted by politicians, especially conservative ones, with every election. Immigration and race remain hallmark dogwhistles in modern politics. The Trump campaign used the slogan "America First" on the campaign trail - echoing the campaign slogan of Woodrow Wilson leading up to his first term as a neutral isolationist. It was a policy he would abandon in his second term, as the U.S. entered World War I in the spring of 1917. Americans were notoriously isolationist in the early 20th century (except for their colonialist ambitions in Central America, Hawaii, and the Phillipines) and America's first propaganda machine had to be created to convince them that joining the war was a good idea. To convince them, Woodrow Wilson invented the idea of defending and spreading democracy (and American exceptionalism) abroad - a policy that has continued to be used in every American war since then. Attempts to Americanize immigrants remained in effect throughout the war. Progressive reformers from settlement houses and canning kitchens on up to proponents for the war which thought a draft would help Americanize immigrants tried to force people into the mold of White Anglo American (usually Northeastern) culture. Black Americans faced similar pressures, and segregated versions of just about every middle-class voluntary organization - including the Red Cross - was implemented during the war. Following the war, newly economically mobile Black Americans, buoyed by industrial jobs for war production, faced even more hostility than before. Resentment by racists clashed with confident (and armed) veterans returning from war. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is just one example of Black WWI veterans attempting to defend themselves and their communities. Race riots, lynchings, and a dramatic expansion of the Ku Klux Klan were the hallmarks of 1919, 1920, and beyond. Today, Black American communities still deal with over-policing, incarceration, and violence. Latinx-Americans have dealt with a dramatic ramp-up of incarceration, family separation, and deportation (even of children), as well as more casual racism. And Asian-Americans in particular have borne the brunt of some horrific incidents of racism directly related to the coronavirus - as the ignorant believe that they (regardless of whether or not they had been to China recently, or were even of Chinese descent) were "carriers" of the disease - another old saw of racism most famously used by Nazis against the Jews (among others). The High Cost of LivingIn the two decades leading up to WWI, the United States underwent a series of depressions and recessions. Starting with the Depression of 1893 (which the US did not recover from until 1897-98), and with smaller recessions in 1907 and 1913-14, the "high cost of living" (commonly abbreviated as "HCL" or "H.C.L.") saw a dramatic rise in cost of living, including food and housing, while wages stagnated. Called "stagflation" by economists, this situation led to labor unrest, and strikes, food boycotts, and food riots were all common during this time period. Socialists were also in political ascendancy due to income and labor inequalities. Labor strikes were often broken by deadly force. Food boycotts and riots remained the purview of the desperate - often women with starving children which tugged at the heartstrings of wealthy and middle-class White Progressives, even as some were organized by socialist activists (read about the 1917 food riots in New York City). Many of the strikes and riots of the 1900s and 1910s led to serious labor reform, including the ending of child labor, worker safety reforms, reduced hours, and more. New York City during WWI tried to pass a minimum wage law, but it was vetoed by the Mayor. Today's parallels include a different sort of high cost of living - most "luxury" items are cheaper than they've ever been, but housing, education, healthcare, and food costs have risen by as much as 200% in the last 20 years. In addition, democratic socialists and real, "bread and roses" socialists have seen their numbers spike in the last few years. Activists are fighting for a minimum wage increase, universal healthcare, and other reforms, although union membership has taken a steep dive in the last few decades. Coronavirus has only highlighted the "essential" role many low-wage workers play in American life, and some retail workers, cleaners/janitors, and restaurant workers are now being hailed as heroes alongside medical professionals and scientists. War Gardens & RationingOne particularly fascinating trend that appears to be occurring right now is the skyrocketing sale of vegetable seeds and plants. Tied in part to the fact that so many Americans are sheltering in place and have time to garden, the resurgent interest in "Victory Gardens" is also a reaction to temporary shortages in grocery stores (due to logistics, rather than supply) and fears that the food supply might be endangered by coronavirus. The First World War was also one of the first times in American history that a concerted effort to get ordinary people to plant kitchen gardens. Of course, part of that was because of the changing demographics of population. People in rural areas had almost always had kitchen gardens. But as more and more people moved into urban and suburban environments, and fresh food supplies became easier and cheaper to acquire, kitchen gardens became less necessary, and most people who could afford to focused on flower gardens instead. But the U.S. entrance into the war, with its commitment to feeding the Allies, came with very real fears that food would be in short supply. This was reinforced by rhetoric from Wilson and Herbert Hoover, the new U.S. Food Administrator, who knew that in the spring of 1917, existing crops would be inadequate to feed both Americans, their growing army, and the Allies without serious changes. Enter war gardens and voluntary rationing. Hoover was the brains behind the idea of voluntary rationing - he wanted Americans to show the world their personal fortitude and strength through voluntary efforts, including rationing. He also believed that the bureaucracy necessary to enforce mandatory rationing would not only be hugely expensive, it would also be ineffective. To lead by example, Hoover and the entire Food Administration were all volunteers. Rationing included refraining from eating wheat, meat, butter, and sugar whenever possible, and by the fall of 1917, "wheatless, meatless, and sweetless" days were implemented. Grain and flour substitutions, sugar substitutions, and vegetarian meals became more normalized during the war. The National War Garden Commission was also a voluntary organization, albeit a private, not public, one. Started by forestry magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, it encouraged Americans, especially school children, to plant "war gardens" (later renamed "victory gardens," a name that would resurface during WWII) which would provide fresh vegetables for ordinary people. Not only would this free up conventional food supplies, the production of local food would also free up transportation resources, which by the end of 1917 were becoming so congested that the United States temporarily nationalized its railroads. Spanish Influenza "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. And, of course, the obvious one. I've already written a bit about the Spanish Flu, but it bears noting that during the course of the 1918 pandemic, the government was reluctant to report real numbers or spread information about the severity of the pandemic because they were worried that it would endanger the war effort or reduce morale. Some cities, like Philadelphia, held enormous and patriotic Liberty Loan parades, allowing the virus to spread like wildfire. In fact, despite evidence that the influenza strain likely started in the United States, it wasn't until neutral Spain was infected, and its newspapers reported the real death toll, that the general public learned of the pandemic. Hence the name, "Spanish Influenza." Similar things are happening now, with the Trump Administration's initial reluctance to admit coronavirus was a serious problem because they feared the effect on the economy. Conflicting information in the media (and from the President) about the severity of the virus and the need for social distancing and stay at home orders have exacerbated the problem here in the U.S. More recently, a dearth of testing has led to some experts to conclude that the death toll is severely underreported. We are now also learning that China has likely suppressed or underreported the true infection rate and death toll from coronavirus. Thankfully, unlike 1918, when newspapers largely cooperated with government propaganda efforts (under threat of having their licenses revoked, effectively putting them out of business), modern information is more accessible and immediate than ever through the internet. Although sifting fact from fiction is a bit more difficult these days. ConclusionThere are a number of other Progressive Era similarities to modern life - women's rights, environmental conservation, voting rights, and income inequality, to name a few - that I chose not to include in this list largely because they were less immediately relevant to the coronavirus pandemic. To learn more about food in World War I, check out my Bibliography page, which was links to lots of great books. I hope you enjoyed this read. It certainly helped me organize my thoughts around these similarities and I hope that we can learn from the successes and failures of the past. That's all any historian can hope. Thanks for reading. Stay safe, stay home. If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

2 Comments

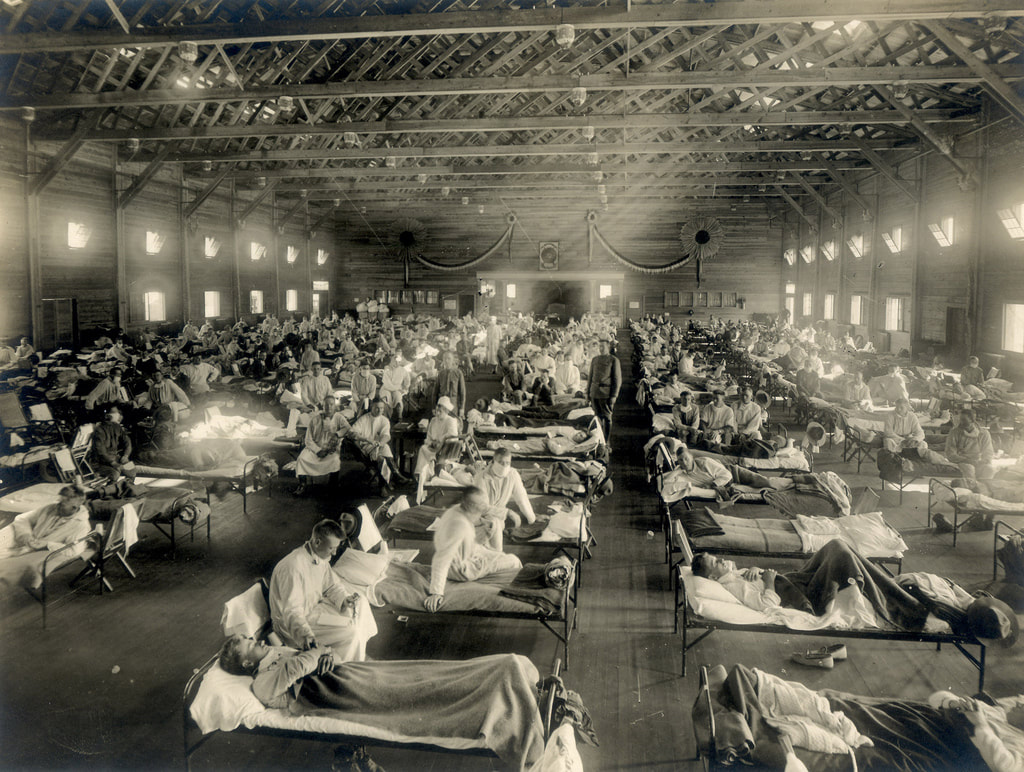

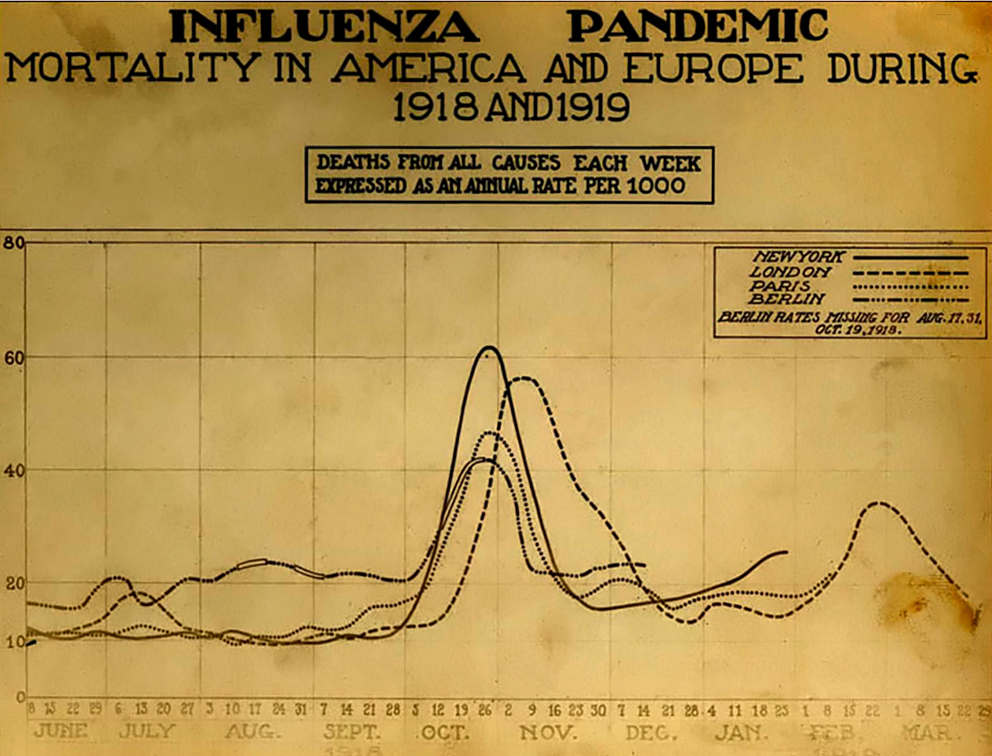

Given the prevalence of COVID-19 around the world, the comparisons to the influenza epidemic of 1918, and a reduction in my hours at work, I finally spent some time today familiarizing myself with the "flu." Folks, it wasn't pretty. The origins of what became known as Spanish Influenza is disputed, mostly because influenza mutates frequently, especially when humans are housed in close contact with animals. Some researchers claim British army camps in France, some claim Austria, some China, many as early as 1917. But one instance is believed to have occurred in Haskell County, Kansas, in January, 1918 (Barry, 110-112). It was a strange new version of the well-known influenza - violent coughing, nosebleeds, pneumonia, and in some cases, skin that turned so dark blue it was difficult to tell if a person was Black or White. And most concerning of all, the disease seemed to strike young, healthy people more than the typical infants or elderly. The influenza ran through crowded conditions during the very cold winter and spring in Army camps in Kansas, including Camp Funston, and then seemed to disappear. But it was spreading across the globe. In May, 1918, it reached Spain and sickened Alfonso XIII, the King of Spain. Unlike the United States and other European nations, Spain was politically neutral. And unlike its neighbors, who refused to reveal any sense of weakness that news of an epidemic might bring, Spain reported about this new strain of influenza in its newspapers. Hence the name, "Spanish flu." By August, 1918, a more virulent strain appeared in France, Sierra Leone, and Boston. By October the disease had become a global pandemic. The vast majority of those who died were under the age of 65. One theory as to why older people, who are typically first victims, would have been spared is that they may have developed immunity as young adults due to exposure to the "Russian flu," an influenza pandemic from 1889-1890. In addition, modern research has determined that the Spanish flu caused a violent immuno-response. The stronger the immune system, the more violent the response. Other factors in the high mortality rate may have included aspirin poisoning, as many of the worst death rates in the United States coincided with the US Surgeon General's recommendation that mega-doses of aspirin be used to treat the symptoms of influenza. Few public records of influenza remain, in large part because few were ever created. Like his counterparts in Europe, President Woodrow Wilson feared negative press and its impact on national morale. By the fall of 1918, he was determined to hammer home victory by sheer force. By that time, the American press, influenced by George Creel's Committee for Public Information and the threat of censorship law, published nothing Wilson wouldn't like. So few references to the influenza epidemic exist in newspaper references, it is almost as if it didn't happen. But happen it did. The public denial of a problem extended to government assistance as well. State and municipal governments were largely left to fend for themselves. The only real advice came from the Surgeon General: "Surgeon General’s Advice to Avoid Influenza

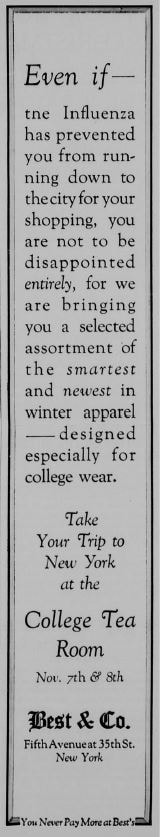

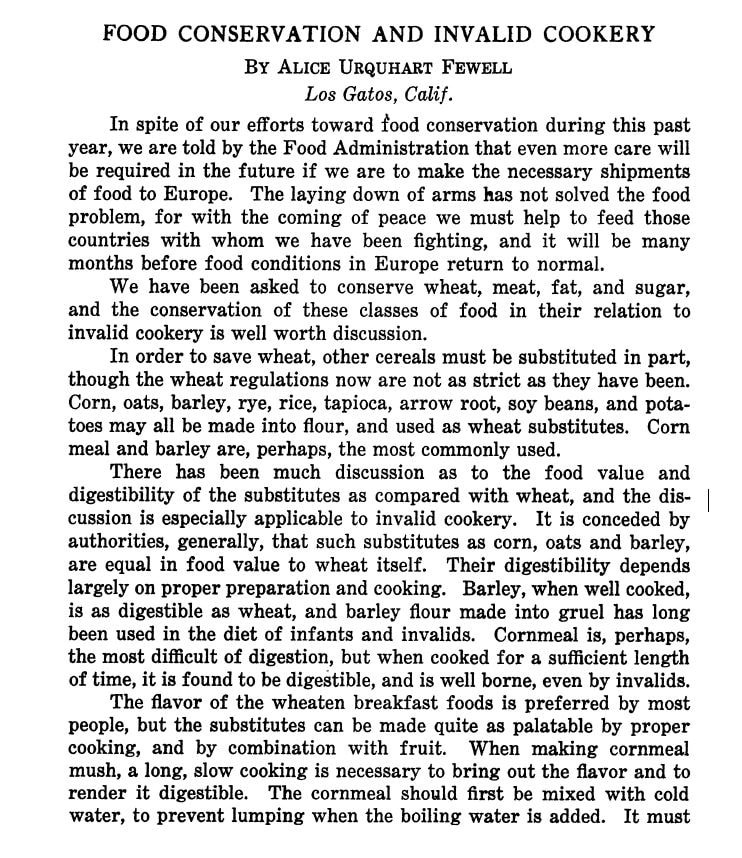

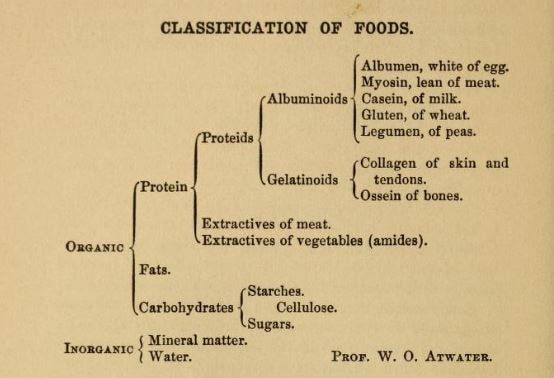

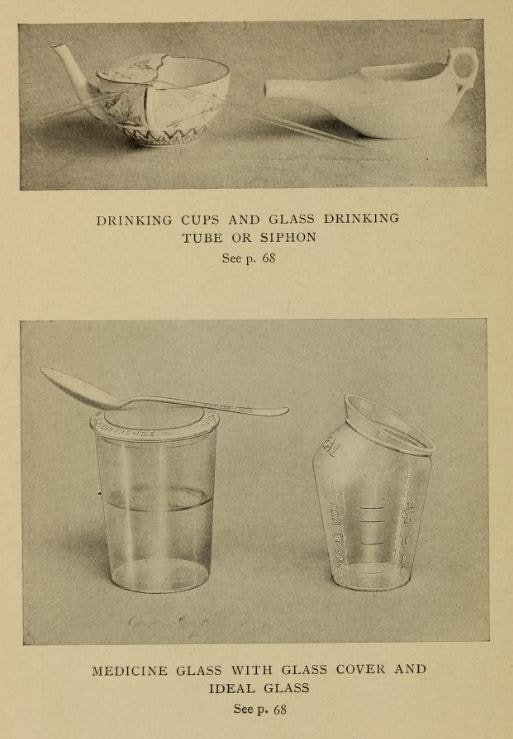

Many cities began to enforce the closure of public places. In recent news, the parable of Philadelphia and St. Louis have come up frequently. Philadelphia didn't shut down public spaces and in fact held an enormous parade, despite the risk. Within three days, people started dying. St. Louis, by contrast, took extraordinary measures to reduce crowds in public spaces, in the face of intense criticism, but had much lower infection and death rates. New York City, although the most populous city in the nation at the time, fared better than neighboring Philadelphia and Boston for two reasons. First, as the major maritime port for the whole Eastern seaboard, it started quarantining influenza cases as early as August, 1918. Second, the New York City Board of Health in early October recategorized influenza, allowing it to be reported as other infectious diseases. This allowed the city to monitor the situation and make decisions such as a staggered business schedule to reduce traffic on public transportation. On October 15, 1918, the New York Times published "Will District City in Influenza Fight," outlining how the city was to be divided up into districts for better organizing. That day, there was a meeting of the Emergency Advisory Committee, including Dr. Lee K. Frankel, who was at the meeting to represent social services organizations in the city. Of the plan to district, he said, "We shall try to find districts with a physical plant where cooking can be done, so as to supply families where there is illness, and the people are unable to care for themselves in connection with supplying food." This is one of the few indications of city-wide organization of cooked food for victims of influenza and its effects. But the pandemic did have a huge effect on the general population, not the least of which was orphaning children and leaving families without a breadwinner. From the 75th Annual Report of the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor [what a name!]: “In handling the influenza epidemic, the report says, the association tackled one of the heaviest problems it has ever had to face in its seventy-five years. As an indication of the widespread effects of the disease the report points out that during the epidemic it cared for 355 families which had never before received aid from any relief organization. From Oct. 1 to March 1, the association took charge of 600 homes where influenza was prevalent. The work still continues. The association is spending $3,000 a month to care for families whose wage earners died during the epidemic. "In reviewing the year’s work, Bailey B. Burritt, the general director, in reference to the influenza epidemic said: “This has meant greatly increased drafts upon the energies of our nursing and visiting corps. It has meant many additional families which have had to be cared for, and some of these families will have to be cared for for many months because of the death of the breadwinner. It has meant the opening of an additional convalescent home for the after care of influenza cases. It has meant also greatly increased expenditures." At Vassar College, one of the Seven Sisters colleges where upper class white women attended, was also involved with pandemic relief efforts. In the November 27, 1918 issue of Vassar Miscellany News, the weekly(ish) Vassar campus newspaper, Helen Morton, Chairman of the General Service Committee of Christian Association, wrote an article entitled "The Epidemic That Was:" "Perhaps you remember? Yes, and the Poughkeepsie people probably do too! Poughkeepsie was well organized to meet the emergency and they were kind enough to let us help where we could. The College as a whole responded wonderfully. Old clothes fairly showered into the box in Main, mixed with toys for the orphans at Wheaton Park. Sheets monograms and all were sacrificed at a moment's notice. Hundreds of swabs and masks were made within half an hour; dozens of night gowns and a few layettes were made within a week. Six hundred odd dollars were collected in three days. One sick freshman even sent a generous contribution from the Infirmary for those who had influenza. With this money We were able to contribute to the support of the City Club "Kitchen." We were able to send food there every day: vegetables, cereals, orange juice, custards, etc.: we were able to help Miss Oxley with her splendid work in Arlington, to help the Associated Charities, and now we can start in on the reconstruction work with substantial support. The Associated Charities said—"It has given us the greatest pleasure to serve as stewards of the Vassar girls in the distribution of the comforts you gave us, and we are anxious to pass on to the owners the grateful thank- of the recipients." Members of the faculty helped us out in carrying things to and from town, and a few, willing martyrs, allowed their car- to be used for everything imaginable. In fact, everybody seemed willing to pitch in and work wherever they were given an opportunity. Was the college always so wonderful — or is the power to adapt ourselves to an emergency, which was so apparent during those trying weeks, one of the lessons of the Great War?" It's not clear why the article is written in the past-tense, as the pandemic continued for several months after November, but perhaps the worst was over in Poughkeepsie by that point. In the December, 1918 issue of Vassar Miscellany News, The Associated Charities of Poughkeepsie wrote a thank-you letter to "the young women of Vassar College," for their donation of $147.59, which was used to purchase food for needy families in the city for Thanksgiving dinner. Elsie Osborn Davis, General Secretary of the Associated Charities wrote, "Many of these families were either past sufferers or still convalescent from the influenza epidemic. *** In no instance where we gave was there an able-bodied man in the family. Households were either fatherless, or else the wage earner was hopelessly ill in hospital or sanitarium, or languishing in jail, or still convalescent from influenza." Although there is a fair amount of information about responses to the epidemic itself, and some references to the fact that food was needed or was delivered, very little is mentioned of what food was used for patients during this time. Cooking for patients at this time was generally called "invalid cookery" (invalids are sick people, rather than people who are not valid). Typical invalid cookery in the early 1900s was focused on soft, liquid, and/or easy-to-digest foods including beef tea and other meat broths, blanc mange and other milk-based puddings, eggs, and cooked cereals like farina (aka cream of wheat), oatmeal, and milk toast. In January, 1919, the American Journal of Nursing published an article titled, "Food Conservation and Invalid Cookery." Although the war officially ended in November, 1918, voluntary food conservation was urged well into 1919 to help feed the Allies - and defeated Germany - through the winter. Author Alice Urquhart Fewell, a home economist who specialized in invalid cookery, outlined how cooks may deal with rationing, including how to cook cornmeal instead of wheat cereals, to use chicken and eggs in place of beef and to avoid other protein substitutes as being too difficult to digest, and how to use sugar substitutes like honey, corn syrup, and maple sugar. In North Carolina, nurses and invalid cooks suggested that patients with fevers be fed an all-liquid diet, advice that was repeated elsewhere. In addition to beef or chicken broth, buttermilk, and malted milk, albumen water was also suggested. Albumen water is water mixed with raw egg white, and sometimes fruit juice, and served chilled. It was sometimes recommended as an alternative to milk for children. Gelatin was another popular suggestion for invalids as it was easy to swallow and gentle on the stomach. Perhaps the best-known resource available to women and nurses during the Spanish Flu epidemic was written by a very famous person indeed. In 1904, Fannie Merrit Farmer (yes, that Fannie Farmer) published "Food for the Sick and Convalescent." Farmer herself suffered a "paralytic stroke" as a teenager and was forced to drop out of school as she convalesced. She eventually relearned how to walk, though she walked with a limp for the rest of her life and used a wheelchair near the end of her life. Perhaps because of this, she became an expert in invalid cookery and was a frequent lecturer on the topic at the Harvard Medical School. Farmer's invalid cookery is very typical of the period, with its focus on broths and other fortified liquids, cooked grain dishes, eggs, custards, fruits and fruit juices, jellies (gelatin), and frozen desserts, with forays into meat, vegetables, and breads. What is unique about this cookbook is the amount of scientific material in it. Farmer's very first chapter starts in on the current, up-to-date nutrition science of the period, outlining information about essential minerals (we hadn't quite discovered vitamins yet) and listing a chart created by William O. Atwater, an influential nutrition science and the person who turned the calorie not only to use in nutrition science, but also into a household term. Today, we know that this chart isn't QUITE right, although it is on the right track. For instance, "albuminoids" is an old-fashioned term for what today are called "scleroproteins," such as collagen, elastin, and keratin - the insoluble structures of proteins. Farmer also discusses how the body absorbs and metabolizes proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. Her second chapter is all about calories, and even includes a math equation for how to determine the caloric values of any food. Her third chapter discusses digestion (a favorite topic of dyspeptic Victorians), and chapter four, which is quite short, puts forth the somewhat radical idea that eating wholesome food, well prepared, and plenty of rest, fresh air, and exercise were far more essential to good health - preventative medicine, if you will - than simply trying to correct existing diseases with drugs. This scientific approach is, of course, entirely on purpose. Not only was Farmer the kind of rigorous, exacting cook that gave us level measurements, she was also clearly extremely interested in nutrition science and wanted to share what she had learned with her thousands (if not millions) of readers. In part to convince them of her authority on the subject, but also I think to give women the tools they needed to care for their own families, or to pursue careers as nurses. Chapters five and six focus on the care and feeding of infants and children and it is not until chapter seven that we finally start to discuss the ideal diet for the ill, including pictures of some very interesting specialized dishware and glassware for feeding prone patients. Some of Farmer's recipes are not as typical as you might expect. For instance, in the chapter on milk (then considered a "perfect food" for its composition of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats), Farmer touts the benefits of koumiss, kefir, and matzoon - all fermented dairy beverages which Farmer claims are more digestible than straight milk. Which, to be fair, they probably were, not the least of which because the vast majority of milk available to Americans at this time was raw and unpasteurized. Even alcohol has a role to play in Farmer's cookery for the sick, and alcoholic beverages mixed with milk and/or eggs (milk punch, eggnog, hot cocoa with brandy are a few examples). Perhaps the most enduring advice from Farmer is that not only should food be digestible and healthy, it should also LOOK and TASTE good as well. A lesson that a lot of hospitals today could learn from. Fannie Merritt Farmer and other home economists and nutrition scientists were all part of the same movement that led American epidemiologists to try to innovate and find cures for pandemics like the Spanish Flu. The Progressive Era was a time when Americans were trying more than ever to understand the world around them and find ways to cure the physical and societal ills of a nation still dealing with the excesses of the Gilded Age. Although they met with varying success, and many of the upper middle-class white professionals leading the charge were far from perfect, they did make strides. The lessons of Spanish Flu were immediate. In New York City, on November 7, 1918, just days before Armistice, the New York Times published an article entitled "Epidemic Lessons Against Next Time." In it, New York City Health Commissioner Dr. Royal S. Copeland outlined the successes of the city's response, including the immediate quarantine of any cases arriving in the Port of New York by ship, which likely helped curb the introduction of influenza into the city. But most successful of all, perhaps, was the public-private partnership that resulted from the cooperation of private voluntary and relief organizations and city government. Including the mobilization of the Mayor's Committee of Women on National Defense, and its sub-committee on food, to organize food production and cooking for the designated district centers - often located in church basements or settlement houses - and the Automobile Committee, in which wealthy New York women used their automobiles to deliver the food to households in need. The Henry Street Settlement, founded and led by public health nurse Lilian Wald, was singled out in the article for special commendation. The Henry Street Settlement still exists today. The lessons of cooperation, faith in the scientific method, and reliance on experts are all important ones to remember today. As always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed