|

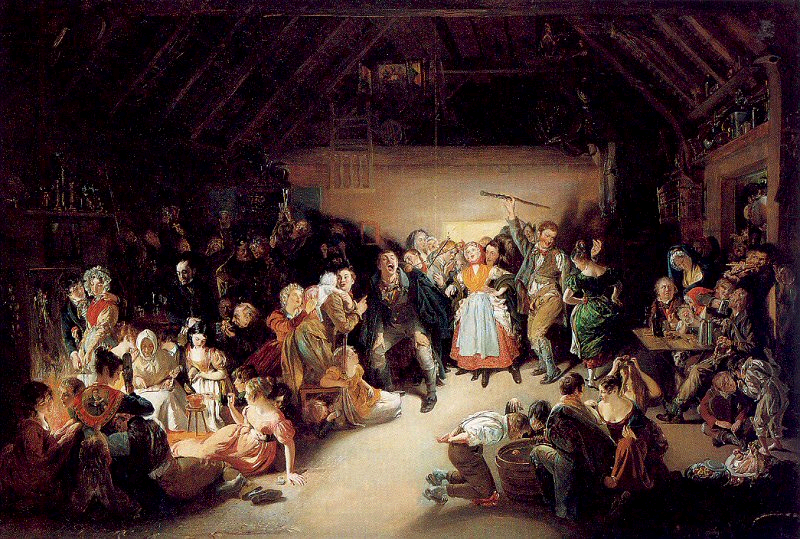

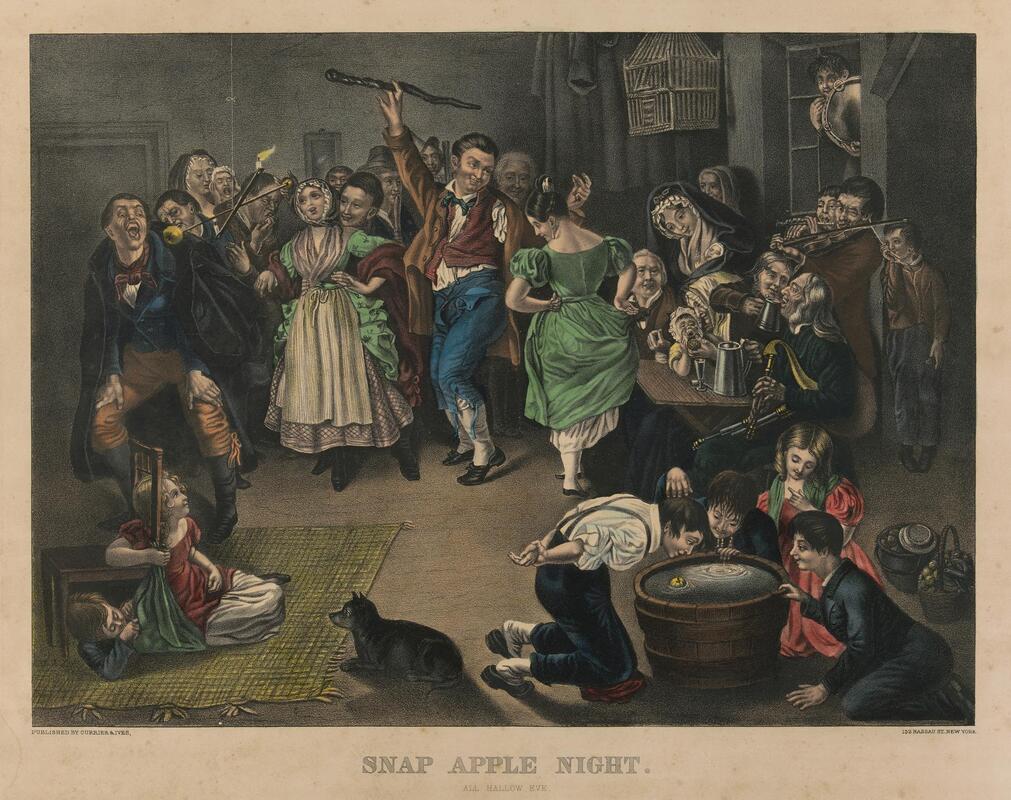

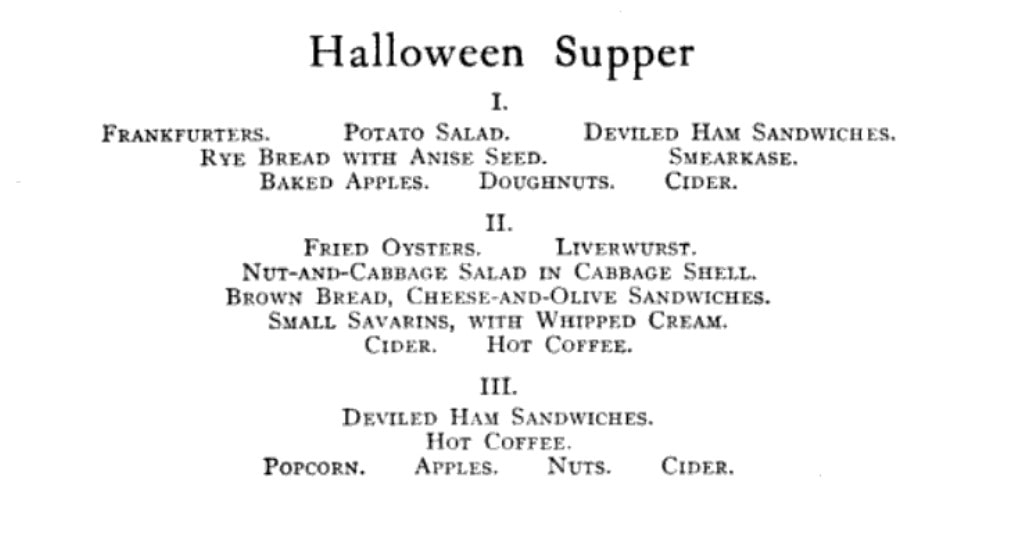

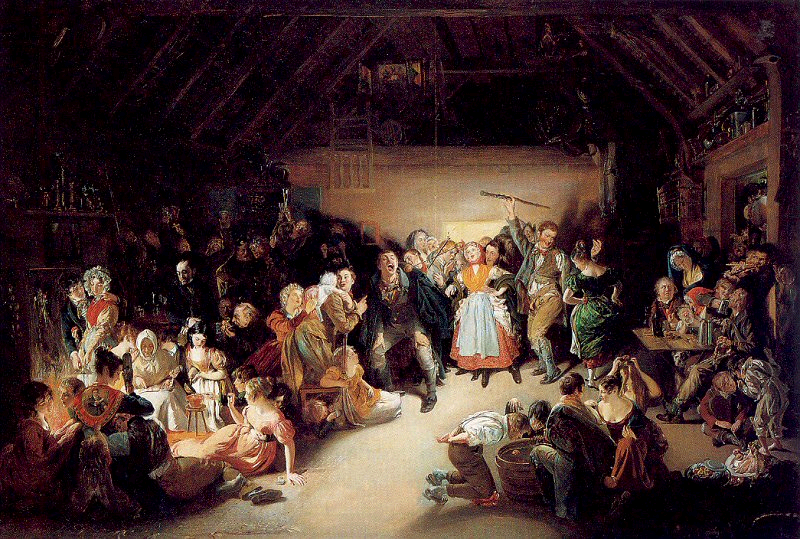

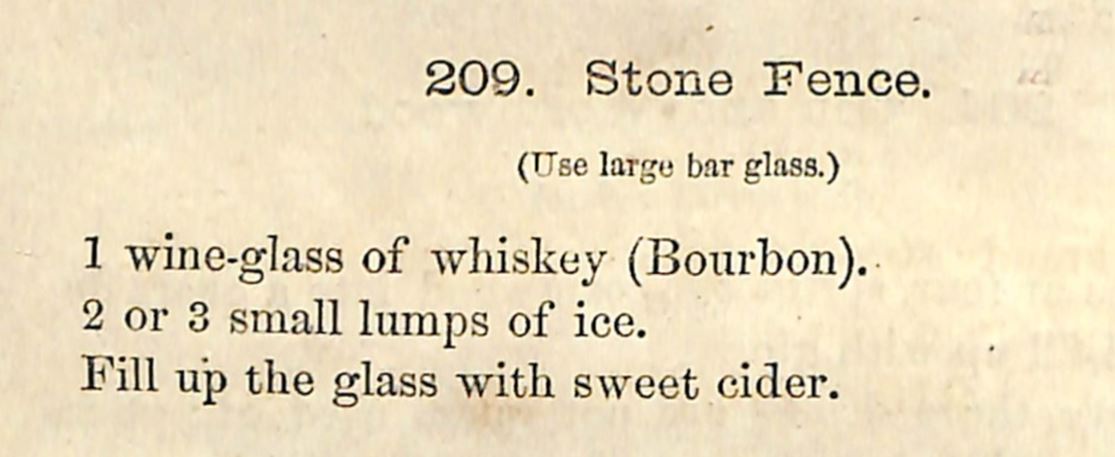

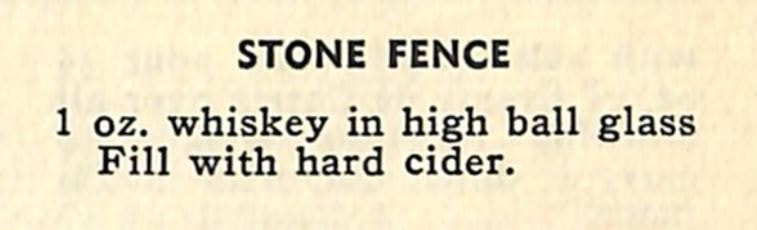

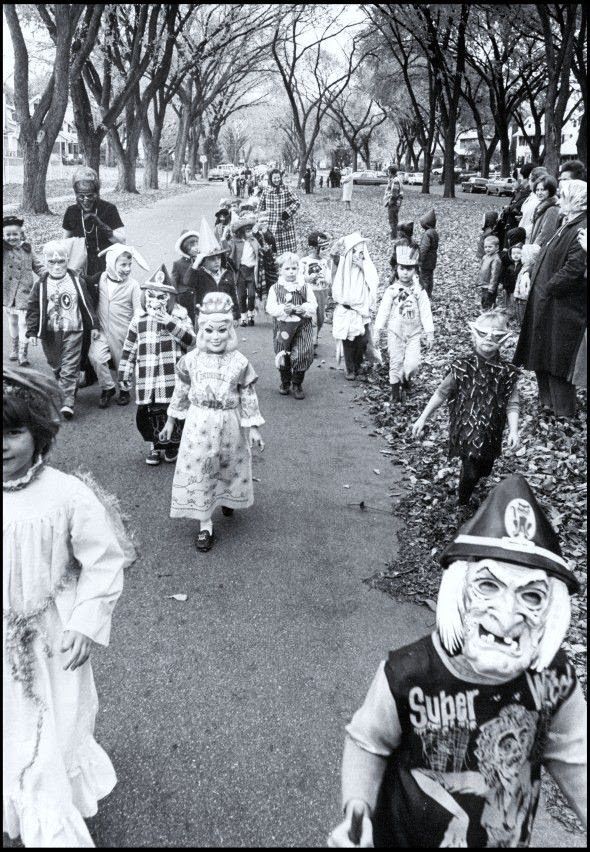

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Happy Halloween, everyone! When it comes to Halloween, pumpkins get all the love. But Halloween's REAL favorite fruit is apples. Let me explain. The origins of Halloween date back to ancient Ireland and Scotland - a place where the now-ubiquitous pumpkin was not available until the 16th century at the earliest, and not really in practice until the 19th century. But apples? Apples were everywhere. They were the best fruit for storing over the long winters. Certain varieties kept better than others, but unlike soft berries or less sweet root vegetables, apples were a reliable source of sugar at a time when calories were all-important. 19th and early 20th century historians often attributed the apple celebrations of the British Isles to Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit orchards, including apples, which in Romance languages share the Latin root word "pomum," meaning fruit. "Apple" was also originally meant to describe all kinds of fruits, not just the Malus domestica, much like "corn" historically referred to all types of grain (and which is why most of the rest of the world refers to it as "maize.") I'm skeptical of the direct connection to Pomona. More likely was simply the fact that apples were in season at this time of year. Apple harvest generally lasts from August through the end of October, depending on the breadth of your apple varieties. Apples were eaten fresh, put up as sauce or apple butter, dried, and processed into apple cider, hard cider, scrumpy, applejack, and apple cider vinegar. But for Halloween, fresh apples were still very common, and a LOT of Halloween traditions involve fresh apples. Snap Apple NightIn Ireland, Halloween was often referred to as "Snap Apple Night," as is illustrated by the classic painting above by Irish artist Daniel Maclise. Maclise based it on a real Halloween party he visited in Ireland in 1832. He illustrates many of the classic traditions. At left, a courting couple burns nuts on the hearth grate to see how their relationship will fare and girls drip molten lead into water to read their fates in the shapes. At right, boys bob for apples and others play pranks on the musicians. And the center, namesake of the painting, is snap apple - a rather precarious and hilarious game. A pair of wooden sticks are fastened together into a cross. On two opposing ends, the sticks were sharpened and apples stuck on. On the opposite ends, burning candles were affixed. The whole thing was hung from the ceiling on a string, and set spinning. The goal was to catch and remove the apple using only your mouth - no hands allowed - without getting hit in the face by a burning candle, or the hot wax. Upon exhibition, Maclise's painting was accompanied by the following poem: There Peggy was dancing with Dan While Maureen the lead was melting, To prove how their fortunes ran With the Cards could Nancy dealt in; There was Kate, and her sweet-heart Will, In nuts their true-love burning, And poor Norah, though smiling still She'd missed the snap-apple turning. As Irish immigrants came to the United States following the great potato famine of the 1840s, they brought their Halloween traditions with them. This rather poorly rendered lithograph by Currier & Ives is a copy of a copy of Daniel Maclise's original painting. Printed in 1853, it reflected the adoption of Halloween by Americans. Missing the divination happening hearthside, this lithograph focuses on the game of snap apple, the dancing and music, and in the foreground, bobbing for apples. This image from the frontispiece of The Book of Hallowe'en, published in 1919 by Ruth E. Kelley, shows the staying power of Maclise's painting, and the power of the mysterious history of Halloween. In this illustration, ("from an Old English print"), we have bobbing for apples and a well-lit game of snap apple. The clothing of the people in the illustration evokes somewhere between the turn of the 19th century and the 1840s - the fuzziness of the time period part of the mystique of the book, which purports to trace the history of Halloween and yes, does link it to the Roman festivals for Pomona. Kelley's book was part of a resurgence of interest in Halloween throughout the United states, and one of a number of books published on the subject, including more serious histories like hers, and more commercial publications like Dennison's Bogie Books. Snap apple remained a popular game, although later versions were slightly safer. As the century wore on and we turned to the 20th century, alternatives went from attaching the apples with strings, to replacing the candles with small sacks of flour (far less dangerous than flame and hot wax, but no less humiliating to get hit in the face with a puff of flour), and eventually simply hanging apples from a string. An even easier later variation even replaced the apples with donuts! As Halloween traditions shifted from at home parties to public events like costume parades and community trick or treating, snap apple faded into obscurity. History of Bobbing for ApplesThe above painting is one of my favorites from the time period. Howard Christy's "Halloween" depicts a very fancy Progressive Era Halloween party that still smacks of the Gilded Age. The decadent mansion, with enormous Classical paintings, gilded furniture, and elaborate gaslights is filled with men in tuxedoes and sleek haircuts and women in glistening silks and satins - nary a fancy dress costume in sight. In the foreground a fancy Classical style fountain has a few apples floating in it, and one young lady bends close - contemplating bobbing, perchance? - while others look on. In the background, a young woman and a man gaze into a mirror - the woman holds a lit taper candle, which evokes the Halloween divination tradition of gazing into a dark mirror by candlelight at midnight. Supposedly your future husband would appear. It's a slightly ridiculous take on the historically very messy and hilarious tradition of bobbing for apples. Like snap apple, bobbing for apples (sometimes known as dunking or ducking for apples), was a game of hilarity, skill, and danger. A large basin - often the wooden laundry basin - was filled with water and apples floated on top. The object of the game was to retrieve them with only your mouth - hands behind your back. There were a number of tricks to retrieve them. Some tried to grab the stem in their teeth. Others used their lips to suction the side of the apple. Still others shoved their entire heads under water, trying to trap the apple between their mouth and the bottom of the basin. Like with snap apple, courting couples could cooperate to sandwich an apple between them. And like snap apple, bobbing for apples drifted into obscurity as the 20th century wore on, although it remained more firmly in the American cultural consciousness than snap apple.  This undated postcard, likely from the turn of the 20th century, features two girls and a boy bobbing for apples. It's one of the few images of the period showing a girl actually doing the bobbing while the other two watch. A smoking jack o'lantern typical of the period sits in the foreground. Toronto Public Library collection. Apple Divination In this 1909 Halloween postcard by illustrator Bernhardt Wall, a young woman is tossing a long apple peel over her shoulder, believing that the peel will fall to the floor in the shape of a letter that will reveal the first letter of her future husband's name. Posted by collector Alan Mays to Flickr. Like May Day and Midsummer, Halloween was chock full of divination opportunities, and apples were at the center of several. The more famous is apple peel divination. A young girl would peel an apple in a long strand - sources vary over whether she had to do the whole apple in one unbroken peel - and toss the peel over her shoulder. Supposedly, the peel would land in the shape of the initial of the man she was to marry. In practice it seems like there would be a lot of S's, C's, L's, and O's, and not too many T's or H's. Another romantic divination game involved the apple seeds. Pressing fresh seeds to your forehead you would assign to each one a crush or romantic interest. The one that stayed on the longest was destined to be yours. Still other apple seed games involved squeezing them in your fingers. The direction they shot out of your fingers was where your true love would approach from. Candy and Caramel Apple HistoryAlthough apples were consumed regularly in the autumn months in northern climes all over the world, it wasn't until the late 19th century that the modern apple as we know it today developed. Starting post-Civil War, fruit orchardists like the Stark Brothers and agricultural college experimental stations began developing specific varieties of fruit, grafted for taste, disease resistance, ripening time, etc. With these scientific developments came the emergence of the modern dessert apple. Designed for eating, rather than for producing cider, these apples were sweeter than their predecessors. Apples, through improvements in orchard husbandry, were also getting larger, more standardized, and shipped better. People in cities were able to access fresh apples on an increasing basis. Which led to innovations in eating. Candying fruits in sugar or honey syrup is ancient. But the idea of dipping fresh apples in a candy coating was relatively new. Candy apples are coated in a shiny red candy glaze, whereas caramel apples are dipped in sticky brown caramel. Taffy apples are somewhere in between. Toffee apples, as they are called in England, are similar to both. Although candy apples are widely attributed to William Kolb of New Jersey in 1908, but toffee apples and caramel apples have newspaper references in England and France in the 1890s. Also in 1908, one newspaper article for "Caramel Apples" went viral - appearing in 62 newspapers across the country. It is not quite the same as the caramel apples we associate with today, which are more similar to British toffee apples of a sour apple dipped in soft caramel. These were more like a combination of the medieval candied apples and modern caramel apples, with nary a stick in sight. Here's the article in its entirety: CARAMEL APPLES ARE GOOD. As you can see from the recipe, these apples must have been incredibly sweet as they were both cooked in syrup and then also covered in caramel and more syrup and served with whipped cream. No wonder the sugar addicts of 1908 made this recipe go viral! Caramel and candy apple associations with Halloween come a bit later, coinciding with the apple harvest season. Most Americans connect them to county fairs and old-fashioned trick-or-treating, when people still made homemade treats to distribute before the candy scares of the 1970s. Today, they're found everywhere from pick-your-own apple orchards to places like Coldstone Creamery, although most are now dipped in chocolate, rather than caramel or candy, as getting a candied coating that is thick enough to stick and soft enough not to break your teeth is a bit of a lost art. Chocolate is far easier to handle. Apple Cider For Halloween MenusAlthough the Pumpkin Spice latte may have taken over fall in today's world, in my opinion apple cider is a much better companion. And historic cooks and party planners agreed. Apple cider was often featured in Halloween menus like the ones above from the late Victorian period on. This would have been sweet cider, of course, because even before Prohibition most home economists and domestic scientists were advocates of the Temperance movement. Whether served cold or spiced, cider was often associated with other more casual foods like doughnuts, popcorn, frankfurters (aka hotdogs), pickles, and nuts. Outdoor events like bonfires, hay rides, and outdoor parties along with public events where children or teenagers were present were also commonly associated with simpler foods like outlined in the menus above. The prevalence of cider reveals its more industrial origins. Apple orchards growing dessert apples were more prevalent, as older heirloom cider apples fell out of use. Commercial bottling in the mid-19th century allowed companies like Martinelli's to produce hard cider and sodas. The growing popularity of the Temperance movement shifted companies away from hard cider and toward unfermented sweet cider, which remains the focus of Martinelli's today. Companies like Mott's also started out making hard cider, and then shifted to sweet in the 20th century as bottling sanitation improved and the demand for non-alcoholic beverages increased. Today, most commercially-sold apple juice is filtered and pasteurized, making for a thinner-bodied, sweeter, and less acidic product. Apple cider is generally not filtered and is sometimes sold unpasteurized, as the acidity level gives it anti-microbial properties. This, along with the sugar content, is generally also what allows apple cider to ferment, rather than spoil. Today, most hard cider is inoculated with champagne yeast, but historically wild yeast would naturally gather in the sugary liquid. Sweet cider is available most places where apples are grown, and New York is the second-largest apple-producing state in the country, so I'm lucky to have ample access to it. I've even made my own with a historic cider press! (Just a small, household sized one, not one of the giant presses.) In all, apples take the cake (sometimes literally) in Halloween eats in large part because they were a readily available source of sugar a time when refined cane sugar was largely the purview of the wealthy. And besides which, although pumpkin pie was also associated with Halloween, there's only so much of it you can eat before you get sick of it. Apples - whether candied and carameled or turned into pie, salads, cakes, muffins, crisps, dumplings, sauce, butter, cider, or even candy - are tough to get sick of, especially after a long, hot summer. What do you thing - do apples beat out pumpkins for ideal Halloween eats? Or should we be celebrating other fruits altogether, like pears or blackberries? Edwardian HalloweenAs I was working on this post, I was watching BBC's Edwardian Farm (which is also available on Amazon Prime - using the link helps support The Food Historian). Episode 2 is great to watch in its entirety (lime burning, apple cider pressing, and egg preservation, oh my!), but I've started the YouTube video below at the beginning of the Halloween party, where you'll see a variation of snap apple, an apple divination game involving sticking apple seeds to your forehead, and of course, fermented apple cider. Enjoy, and have a happy, apple-ish Halloween! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

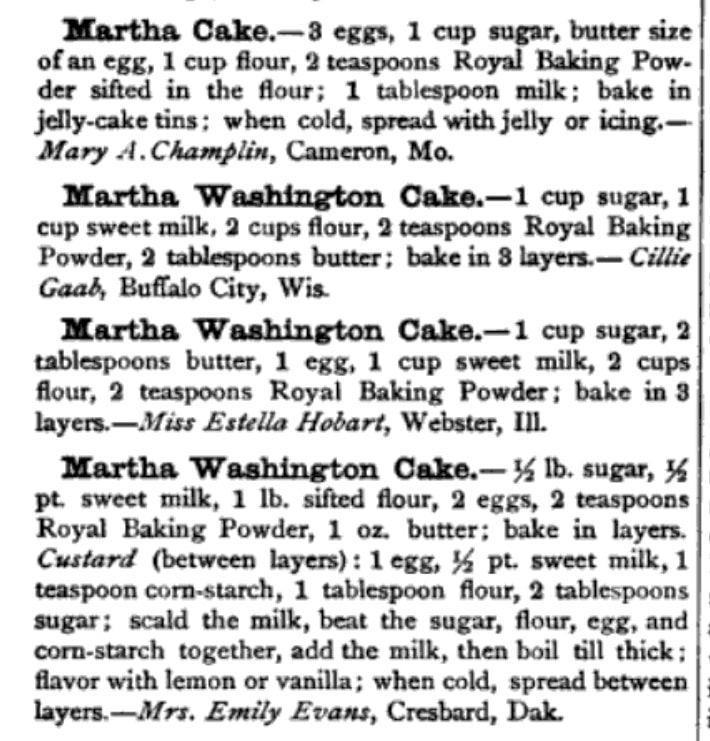

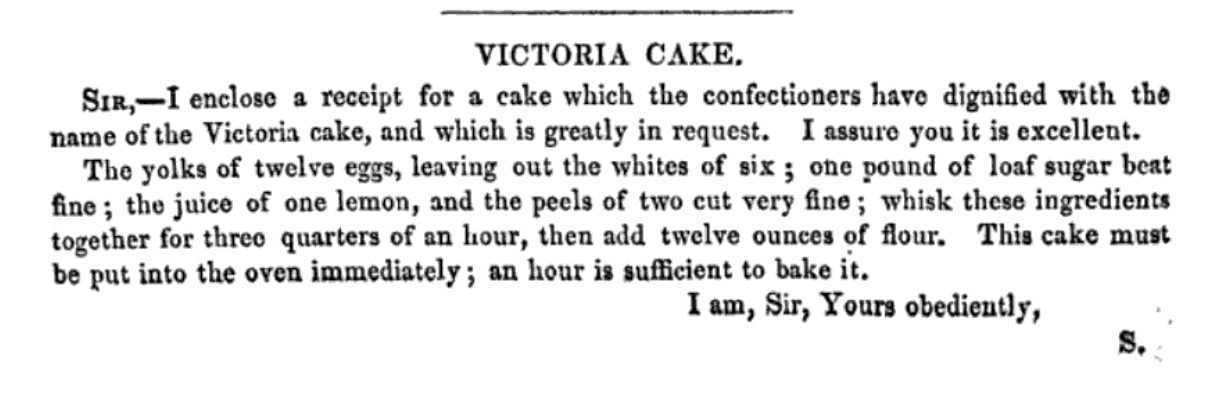

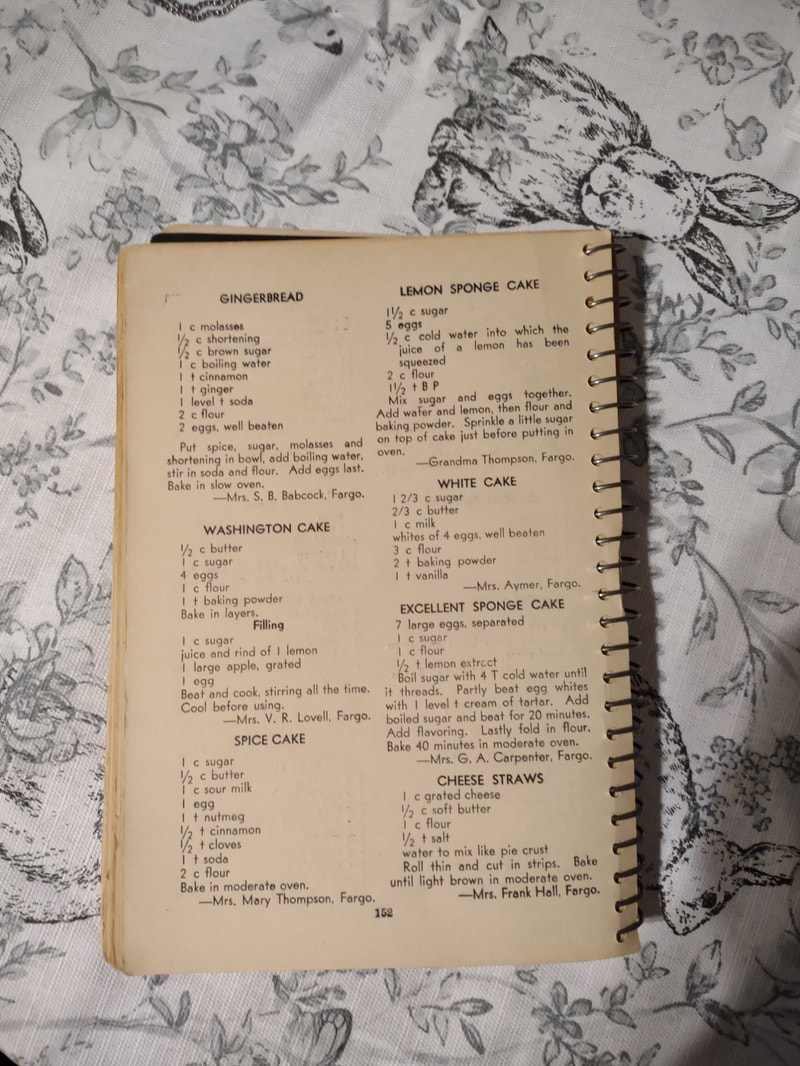

Washington Pie HistoryWashington pie is everywhere in 19th century cookbooks. Confusingly, it is not a pie. Gastro Obscura traced the history of Washington pie, but spoiler alert - it was called a pie because it was baked in tin pie pans, which back then had straight sides similar to modern cake pans. WHY it was named after George Washington isn't clear - and the earliest references we can find date to 1850. Gastro Obscura and Patricia Reber trace it back to Mrs. Putnam's Receipt Book and Young Housekeeper, by Elizabeth H. Putnam and published in 1850. But I found another reference from 1850, the Practical Cook Book by Mrs. Bliss (of Boston), also published in 1850, for "No. 1 Washington Cake," which included the note "This cake is sometimes called WASHINGTON PIE, LAFAYETTE PIE, JELLY CAKE, &c." Mrs. Bliss' recipe is preceded by the lovely-sounding "Virginia Cake," which calls for sieved sweet potato and molasses, and "Victoria's Cake," which is a lemon-flavored sponge cake with no mention of the jam and cream commonly found in Victoria Sponge. I did find several earlier references to "Washington Cake," many of which were more a type of white fruit cake with currants (Mrs. Bliss' "No. 2 Washington Cake" is of this type), not a layer cake with jelly, with one exception. "Washington Cake" in Mrs. T. J. Crowen's 1845 Every Lady's Cook Book calls for a similar style cake flavored with lemon and brandy. However it does not say to bake it in layers, nor fill it with jam or jelly. But let's take a harder look at that "Layfayette Pie" reference from Mrs. Bliss. Lafayette Pie, Martha Washington Pie or Cake HistoryAlthough Washington Pie is traditionally made with only jam or jelly, there was another variation that shows up later: the Lafayette or Martha Washington Pie/Cake. Similar to Washington Pie, both "pies" are a simple cake baked in thin layers, but instead of filled with jelly or jam, are filled with custard (or more rarely, whipped cream). Confusingly, though the majority of references to Lafayette Pie and Martha Washington Pie call for custard, I have seen occasional references to jelly options, too. The above recipes, from My Favorite Receipt, published by the Royal Baking Powder Company in 1886 is one of the earliest references I can find to Martha Washington Cake/Pie. The first one, called just "Martha Cake" calls for it to be baked in "jelly-cake tins" and spread with "jelly or icing." The next two recipes are identical, and call for the cake to be baked in three layers, but no reference to fillings. The final version (from a North Dakotan!), is the one which also lists the cooked custard filling, to be flavored with vanilla or lemon. The earliest reference I could find for "Lafayette Pie" is Mrs. E. Putnam's 1867 version of her Mrs. Putnam's Receipt Book, which follows the Washington Cake recipe with "Lafayette Pie," a rather less precise recipe than Washington's, which is "enough for two pies" and is followed with "Filling for the Above Pies," seeming to mean both Washington and Lafayette. It reads "Two ounces of butter, quarter of a pound of sugar, two eggs, and one lemon; beat all together without boiling." At first, I read this to mean uncooked, but instead it must mean heated but not boiled - essentially a rich, lemon-flavored custard. The Methodist Cook Book, published in 1899, contains a recipe for "Lafayette Pie," which calls for being baked in a "Deep pie plate," and then cut in half lengthwise (confusingly, it says to "cut out the center to make room for the filling") and filled with a cornstarch-egg custard. Just like Martha's. Boston Cream Pie History As far as I can tell, Lafayette Pie and Martha Washington Pie/Cake are essentially the same: a simple layer cake baked in pie tins and filled with cooked custard. Sound familiar? Recipes called "Boston Cream Pie" were for decades exactly the same - a thin plain layer cake filled with a cooked custard. Contrary to what Gastro Obscura claims, when Americans made Boston Cream Pie at home in the 19th century, it was WITHOUT a chocolate topping. None of the 19th century recipes I could find titled "Boston Cream Pie" (and there were many) contain chocolate at all - only one Maria Parloa recipe calls for chocolate, and that is named "Chocolate Cream Pie." Chocolate-free Boston Cream Pie recipes continue to be published into the 1940s. As far as cookbooks go, Boston Cream Pie doesn't morph into the chocolate-topped version until the 20th century. The Home Dissertations cookbook, published in 1886, includes a recipe for "Boston Cream Pie" among its pastry recipes, even though it is clearly a cake. It calls for the cake to be baked in "round tins so that the cake will be one inch and a half thick" and filled with a cooked custard made with eggs and cornstarch, flavored with vanilla or lemon. No chocolate in sight. How or why all of these "pies" which are really cakes got their names remains lost to history. Likely, the cake was baked in honor of Washington's birthday, or other patriotic occasions. Washington's Birthday became a federal holiday in 1879, which may explain the popularity of the cake at the end of the 19th century. Lafayette and Martha likely followed as other patriotic homages. Other political figures also got their due, like this "Mrs. Madison's Cake" from 1855, which lists just above a white fruitcake-style "Washington's Cake," "Madison Cake" from 1856, and "Mrs. Madison's Whim," a similar-style cake "good for three months" stays in print as late as 1860. Even Jefferson got his own cake, although only in one 1865 edition of Godey's Magazine, and it reads more like a sweet biscuit than a true cake. Political cakes may have been a thing in the 19th century, because the 1874 The Home Cook Book of Chicago has an Adams Cake, a Clay Cake, two Harrison Cakes, and a Lincoln Cake, and the Adams and Clay cakes (named for President John Adams and Senator Henry Clay, one presumes) read very much like Washington Pie. There are also TWO recipes for "Washington Pie," one of which has a filling that includes apples. I could only find one other "Lincoln Cake" in the 19th century, published in 1863. And Boston? It could be that the patriotic cakes were simply popular in Beantown, which leant its name as the "pies" spread elsewhere (a la Boston Brown Bread, Boston Baked Beans, etc.). Certainly the Parker House Hotel in Boston claims to have invented Boston Cream Pie, although I've yet to see any hard evidence (like a recipe or period description) that indicates it had a chocolate topping in the 1860s. Victoria Sponge Cake HistoryWashington Pie really is quite similar to Victoria Sponge, which if you're a fan of the Great British Bakeoff, you know is one of Britain's (and Queen Victoria's) favorite desserts. And, ironically, not actually a sponge cake, as it calls for butter (true sponge cakes have no fat). Likely developed in the late 1840s, coinciding with the development of baking powder in 1843, and adopted by the Queen in mourning in the 1860s. Like Washington Cake, some of the first references to "Victoria Cake" are much closer to a white fruitcake or pound cake than a sponge, like this recipe from 1842, or this recipe from 1846 by Francatelli. The first recipe to a sponge-style Victoria Cake comes in 1838, the year after she became queen (recipe pictured above) from The Magazine of Domestic Economy. Although it does not call for filling of either jam nor whipped cream. The oft-cited recipe published in The Practical Cook (1845), is identical to the 1838 recipe, down to the letter. Of course, Mrs. Bliss' "Victoria's Cake," published in 1850, while not identical to the letter, is certainly just a slightly re-worded copy. Despite the popularity of the sponge, "Victoria's Cake" continues to be the yeasted fruitcake that Francatelli and later Soyer keep pushing well into the 1860s. "Victoria Sandwiches" come into play in the 1850s, whereby pieces of sponge cake are sandwiched with jam and topped with pink icing, a la The Practical Housewife, published in 1855 by Robert Kemp Philp. Ridiculously, Francatelli's version of "Victoria Sandwiches" are a literal sandwich, made with hard boiled egg and anchovies. Not quite as flattering to the queen. Mrs. Beeton wisely hops on the sponge cake "Victoria Sandwiches" bandwagon in the 1860s. Although curiously none of these early recipes call for whipped cream to accompany the jam. Perhaps because Mrs. Beeton's recipe for Victoria Sandwiches is immediately followed by one for Whipped Cream, maybe someone put two and two together. Which cake was inspired by whose we'll perhaps never know. Unless some manuscript cookbook has in it somewhere "Washington Pie, from Victoria's Cake" or "Victoria Sandwiches, in the style of Washington Pie." Regardless, it was the exact right kind of cake to associate with heads of state, apparently, once everyone got over heavy white fruit cakes laden with lemon and currants and alcohol. In making a birthday brunch for a friend, I wanted to focus on vintage recipes and had Washington Pie already in mind. But unwilling to use the internet (cheating!), I instead consulted my historic cookbooks. I had been on the lookout for another recipe, when I found a recipe for "Washington Cake" in one of my North Dakota community cookbooks, this one dating to the 1940s: The North Dakota Baptist Women's Cook Book. The cookbook does not have a publication date, but there is a reference to 1947 in the frontspiece, and from that and judging by the style of font and print, we can safely date it to the late 1940s, possibly 1950, but not much later. Interestingly, the recipe for Washington Cake was in a section in the back called "1905 Recipes" and dedicated to the women of the First Baptist Church of Fargo, ND, which was built in 1905. The recipes that follow were all written by women of the church for that first construction - likely from an older cookbook. The dedication reads, "In loving memory of those who have made a very definite contribution to the Christian cause through their labors in the First Baptist Church of Fargo, N. D., and who have left behind them fruits that are being utilized in this book, this page is gratefully dedicated." It then lists two biblical references to death and a list of women's names. The recipes read as much older than 1905, with emphasis on things like brown bread, suet pudding, doughnuts, gingerbread, and mincemeat. Likely they were submitted as "colonial" or similar "old-fashioned" recipes that were part of the popular colonial revival that began at the turn of the 20th century. The recipe for "Washington Cake" was contributed by Mrs. V. R. Lovell of Fargo, ND. It reads: 1/2 c butter 1 c sugar 4 eggs 1 c flour 1 t baking powder Bake in layers. Filling 1 c sugar juice and rind of 1 lemon 1 large apple, grated 1 egg Beat and cook, stirring all the time. Cool before using. Not exactly the most descriptive recipe I've ever read, but better than many! I decided not to use the interesting-sounding filling, although I may revisit it at a future date. Instead, I wanted to go the jam-and-cream route. 1905 Washington Cake (or Pie), AdaptedUnlike a traditional sponge cake, which can be quite finicky with separating egg whites, I found this recipe to be just as delicious, but much simpler. As an added bonus, you don't have to split a taller cake evenly lengthwise - the layers are already thin enough to stack as-is. You can use any kind of jam, but I chose my favorite brand of strawberry. 1/2 cup butter 1 cup sugar 4 eggs 1 cup flour 1 teaspoon baking powder 1 teaspoon vanilla (or lemon or extract) Strawberry jam Whipped cream Preheat the oven to 350 F. Butter well two round cake pans. Cream but the butter and sugar together, then add the eggs one at a time, beating after each addition. Add the vanilla (or lemon), then the flour and baking powder, then mix well until everything is well combined. Pour equal amounts into the two cake pans, then bake on the center rack for approximately 30 minutes (check after 20 - when the cake is golden at the edges and the center springs back to the touch, it is done). Tip the cakes out of their pans onto a cooling rack and let cool completely. Then spread strawberry jam on one layer, and top with whipped cream (I stabilized mine with cornstarch - which you could taste, so I would not recommend doing that again), then add the second layer, more strawberry jam, and more whipped cream. If you want this cake to keep better, I would recommend going the traditional Washington Pie route and just filling thickly with strawberry jam, and serving it with whipped cream on top to taste. This cake is very easy, bakes relatively quickly, and tasted delicious. It was VERY sweet, so I might cut back on the sugar slightly if I make it again. But while I'm sure Great British Bakeoff experts would criticize the fact that I didn't weigh my ingredients or make sure my eggs were room temperature, I thought the cake turned out very lovely indeed. And the combination of cake, whipped cream, and sweetened fruit can never be wrong. As for all the other political cakes? I may have to do some more investigative baking for Presidents' Day 2023. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? You can leave a tip!

Thanks to everyone who joined me for Food History Happy Hour tonight! We talked about the history of diets, dieting, and diet culture, with forays into 19th century religious diets (including Sylvester Graham, Ellen H. White, and John Harvey Kellogg), raw food diets, veganism, changes in fashion influencing ideas about body types, the role of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and WWI in informing modern ideas about dieting, willpower, and health, the invention of the calorie, the development of dieting and diet fads in the 1930s and '40s, including juicing and the Hollywood diet, we talked about Dr. Norman W. Walker, Gaylord Hauser, Dr. Weston Price, Adele Davis, the role of animal fats in heart disease research, the history of artificial sweeteners, environmental factors in fatness and obesity, and that diet culture is super toxic! I probably could have talked for another hour on this subject, so we can revisit it, if you want to! Let me know in the comments.

We also made a (red) wine spritzer (I thought it was a bottle of white wine, it wasn't) and the history of wine spritzers. Wine Spritzer (19th century)

White wine spritzers are the classically low-calorie bar favorite in the late 20th century United States, but they date back to the early 19th century and are likely associated with the health and spa culture surrounding sparkling mineral waters, but may have also been simply an attempt to make an artificially sparkling wine!

Take your favorite wine - red or white - chilled, and cold club soda or seltzer or sparkling mineral water, also chilled. You can combine them in any ratio, but I think half and half is probably best. Further Reading:

Obviously, I had a blast doing this episode and I think I need to now do some biography blog posts about fad diets and nutritionism and their proponents. Did you know Gaylord Hauser had a TV show? You can alsowatch an interview with Adelle Davis!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

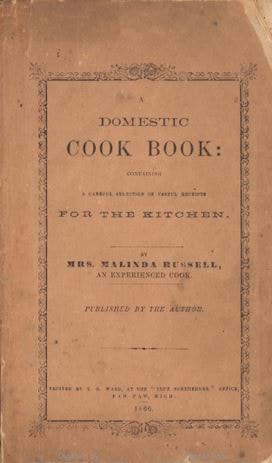

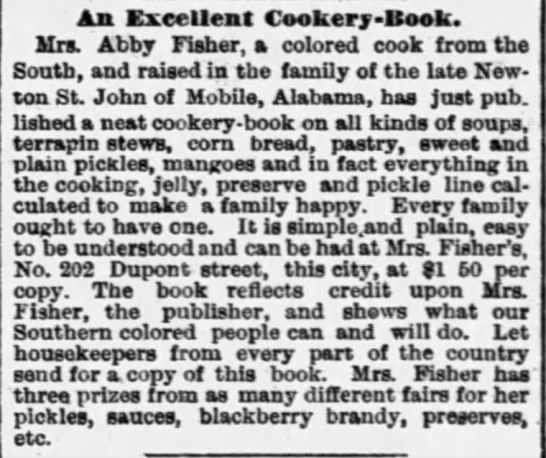

Throughout the 19th century, white women used their domestic assets to pick up the slack left by disabled or deceased husbands - homes became boarding houses and tea rooms and domestic skills were translated into magazine articles and cookbooks. But free Black women in the 19th century did not have as many assets. And even when they did, these assets were often taken from them, and a racist and sexist judicial system gave them little recourse to recover property. Enslaved women freed by the Emancipation Proclamation had their freedom, but little else. The promised 40 acres and a mule never materialized. Despite these often difficult starts, many free and formerly enslaved women of color used their wits and skills to make their own way in the world. Often relegated to service jobs in households, many women created their own small businesses to avoid working for wages - tea rooms, boarding houses, laundries, seamstress and millinery shops, catering, etc. Most of these jobs had low startup costs and could be done from home, allowing for the care of children and family members. Many women also worked as professional cooks for taverns and hotels, a job that held more promise of profit and respect than working in a private household. The vast majority of women working in these fields remain hidden from history - unnamed and un-written-about. But some women of color have managed to make their mark on food history. Here are a few of their stories. Anne Northup - Twelve Years AloneAnne Northup was my first real encounter with the stories of adversity and perseverance many Black women faced throughout the 19th century. I attended a special program at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City with a historic dinner recreated by The Food Griot - Tonya Hopkins. Anne Hampton was born in 1808 in upstate New York. A free woman of color, she married Solomon Northup in the 1820s and in 1834 they sold their farm and moved to Saratoga. Solomon often worked as a fiddler and Anne worked as a cook and kitchen manager at hotels in the spa resort town. She was working at the Pavilion Hotel in Saratoga when she met wealthy white New Yorker Eliza Jumel in 1841. Divorcee/widow of Aaron Burr, Madame Jumel convinced Anne to come south and serve as a cook in her household. Anne sent her eldest daughter Elizabeth to Manhattan with Jumel, but waited until later in the year to come south herself, likely finishing out the busy tourist season. Earlier that summer of 1841, Anne's husband Solomon had answered an advertisement looking for musicians for a job in Virginia. An accomplished violinist, Solomon had answered the advertisement and traveled south. He was captured and sold into slavery, spending the next twelve years enduring brutal conditions on a Louisiana sugar plantation. Anne was left to fend on her own. After a year in Eliza Jumel's household, Anne and some (but not all) of her children returned to Saratoga, where they stayed until 1850, when they moved to Glens Falls and Anne continued her hotel work. They were not reunited with Solomon until 1853. He wrote a book about his experiences - Twelve Years a Slave. We lose track of Solomon Northup in the 1860s and his death date is unknown, although Anne and her children continue to live in New York. To learn more about the Northup family, read this excellent account by historian David Fiske. Anne Northup died on August 8, 1876 in Moreau, New York. Although she leaves behind no documentation of the food she cooked, given her positions in fashionable resort town hotels and wealthy households, she was likely very skilled in a variety of foodways. To me, she represents how many free women of color made their way in the world on the strength of their cooking skills, even in the face of extraordinary adversity. Malinda Russell & Her Union PrinciplesIn 2000, Jan Longone ran across a slim, crumbling cookbook wrapped in brown paper at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where she is curator of American culinary history. That cookbook, A Domestic Cookbook, published in 1866 by a woman named Malinda Russell, turned out to be the earliest known cookbook published by an African American woman. The cookbook has since been digitized, and when I read it for the first time the other day, I was struck by the incredible hardship Russell had to overcome in her life. In the autobiographical account that explains why she wrote the cookbook, Russell recounted the many setbacks in her life. Born free in Tennessee, at age 19 she set out to emigrate to Liberia, a promise of life free from the racism and oppression that continued to plague free Black communities in the North. But along the way, she was robbed by someone from her party, and was forced to stay in Virginia, where she made a living as a cook and a nurse. There, she married Anderson Vaughn, and they had a son together, but Vaughn died just four years later, leaving Russell a widow with a handicapped son. She moved back to Tennessee and opened a boarding house in a town that featured springs as a tourist attraction. She later opened a pastry shop in that same down and had saved up a sum of money to support herself and her son. But in early 1864, she was attacked and robbed by a "guerrilla party," likely Confederate soldiers. She and her son fled Tennessee during the height of the Civil War. Although Tennessee was a Union state, its proximity to the border meant it was not safe for Russell. She made her way to Michigan, enduring several attacks along the way, and went on to start over, again, in a new state. In May, 1866, she published A Domestic Cookbook. She closed her introduction stating that she hoped the sale of the cookbook would help her raise funds to return to Tennessee and reclaim some of her lost property when peace was restored. We do not know if she ever made it home to Tennessee, or really much else about her at all, although Jan Longone has worked to find more about her. According to Russell herself, "I have learned my trade of Fanny Steward, a colored cook, of Virginia, and have since learned many new things in cooking." She also indicated her cookbook was organized along the lines of Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife (1824). Malinda Russell reset much of the conventional wisdom about Black cooking heritage at the time it was rediscovered. But her cookbook is not much different from any other cookbook of the period - reflecting her experience as a boarding house owner and cook, cooking for the public and likely for audiences diverse in race and socioeconomic status. It also knows its audience, consisting largely of dessert and preserves recipes. These were commonly featured in published cookbooks because they were more complex than the everyday cooking of meat and vegetables and less likely to be familiar to ordinary cooks. Her cookbook contains everything from the humble "Baked Indian Meal Pudding" and 'Sliced Sweet Potato Pie," to the exquisite "Floating Islands" and "Charlotte Russe." For me, the most striking thing about Russell is not the content of her cookbook, but rather the fact that it exists at all - a testament to her difficult life and the grit she used to persevere. What Abby Fisher Knew "Pickles and Fruit. The purest home-made Pickles and Preserves of all kinds, put up in the good old Southern style. A liberal discount to the trade. Address, Mrs. Abbey Fisher and Husband, 569 Howard St. San Francisco." Advertisement from the December 13, 1879 issue of "The Placer Herald," published in Rocklin, CA. Unlike Anne Northup and Malinda Russell, Abby Clifton was born into slavery in 1831 in South Carolina to a white father and an enslaved mother. It is unclear when gained her freedom, but by 1860 she had moved to Alabama and married Albert Fisher. In 1877, they emigrated to California and by 1880, Abby and Albert were in San Francisco, where the 1880 Census listed Abby as a "cook" and Albert as a pickle and preserve manufacturer. But this attribution was likely due to sexism common among census takers. In reality, it was Abby who was manufacturing pickles and preserves - as listed in an 1882 San Francisco directory. Albert was listed as a porter. Abby leveraged her expertise in pickles and preserves to reach the highest echelons of San Francisco society. She was awarded a diploma at 1879 Sacramento State Fair. At the 1880 San Francisco Mechanics Institute Fair, she won a bronze medal for her pickles and preserves. Although she and Albert could not read or write, in 1881 she published the cookbook, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. with assistance from white friends who helped her translate and transcribe her memorized recipes into cookbook format. The book does not contain just pickles and preserves, although they and her famous blackberry cordial certainly make a showing. The title inclusion of "Old Southern Cooking" is certainly apt, given recipes for "Maryland Beat Biscuit," "Plantation Corn Bread," "Ochra Gumbo," "Creole Chow Chow," "Sweet Potato Pie," and "Peach Cobbler." But it also includes typical British-American foods popular in the Northeast and throughout the United States, including "Sally Lund" bread, "Jumble" cookies, "Sauce for Suet Pudding," "Rhubarb Pie," (rhubarb grows poorly in the South, needing below freezing temperatures), three different kinds of "Sherbet," "Yorkshire Pudding," and "Terrapin Soup." In short, her cooking is more representative of broad American style cooking of the period, with some Southern flavor, rather than stereotypically "Southern" (i.e. Black) cooking. The interest in Southern cooking, as evidenced by the marketing of her book, was likely part of a reaction to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Historian Megan Elias has written about "Lost Cause cookbooks" in which white Americans romanticized the "good old days" of slavery and subservient Black folks with "magic" cooking skills. It is possible that Abby Fisher's cookbook was swept up in the wave of racist nostalgia. But it is also possible that Abby's cookbook was simply a reflection of the interest in California residents in the cuisines of many newly arrived emigrants of all cultures and backgrounds. This seems to be the case in one announcement, published in the San Francisco Examiner on July 11, 1881. It reads: "An Excellent Cookery-Book. "Mrs. Abby Fisher, a colored cook from the south, and raised in the family of the late Newton St. John of Mobile, Alabamaa, has just published a neat cookery-book on all kinds of soups, terrapin stews, corn bread, pastry, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes and in fact everything in the cooking, jelly, preserve and pickle line calculated to make a family happy. Every family ought to have one. It is simple and plain, easy to be understood and can be had at Mrs. Fisher's, No. 202 Dupont street, this city, at $1.50 per copy. The book reflects credit upon Mrs. Fisher, the publisher, and shows what our Southern colored people can and will do. Let housekeepers from every part of the country send for a copy of this book. Mrs. Fisher has three prizes from as many different fairs for her pickles, sauces, blackberry brandy, preserves, etc." Although we may never know how many copies Abby sold, the cookbook seemed to garner positive reviews. For several weeks in 1881, she (or the publisher) advertised it in the Oakland Tribune (see below).  "Mrs. Abby Fisher's, Southern Cookery book on soups, terrapin stews, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes, preserves, corn bread; price $1.50; 202 Dupont st., San Francisco. jy11-1m." Advertisement for Mrs. Fisher's cookbook in the "Oakland Tribune," published July 11, 1881, but running for several weeks prior and after. In the 1890 San Francisco directory, "Mrs. Abbie Fisher" was still listed as "mnfr. pickles and preserves," but it is unclear what happened after that. Her exact death date is also unknown. No known obituary was published. After the Great San Francisco Fire of 1907, reference to Abby and her cookbook all but disappeared until a copy surfaced in 1984 at a Sotheby's auction in New York City. The Schlesinger Library purchased it and at the time it was thought to be the first cookbook published in the United States by a Black woman, until Malinda Russell toppled Abby from her throne in 2000. Like Malinda and Anne, Abby used her cooking skills to make her own way in the world - supporting her family and showcasing her talents. Ghosts in the KitchenOf course, we know about these women because they left a written record. We know about Anne through her husband Solomon and his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave and the records of Eliza Jumel. We know about Malinda because of her cookbook and the autobiography she includes in it. And we know about Abby because of her cookbook and her existence in newspapers and city directories. But there were tens of thousands of women of color making their own way on the strength of their culinary skills, just like these women, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Ashbell McElveen called James Hemings the "ghost in America's kitchen," but he wasn't the only one. Enslaved women and men shaped American food profoundly. And women of color - enslaved, freed, and born free - left their mark as well. Because I know how history works, I am hopeful that more records and cookbooks of cooks of color - published or not - will continue to show up in the coming decades. And when they do, I know they'll help us better understand how our food got to be the way it is, and where it can go in the future. Further ReadingAnne Northup:

Malinda Russell:

Abby Fisher:

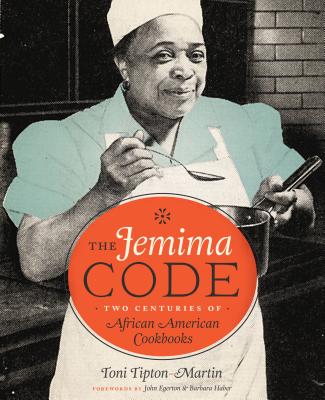

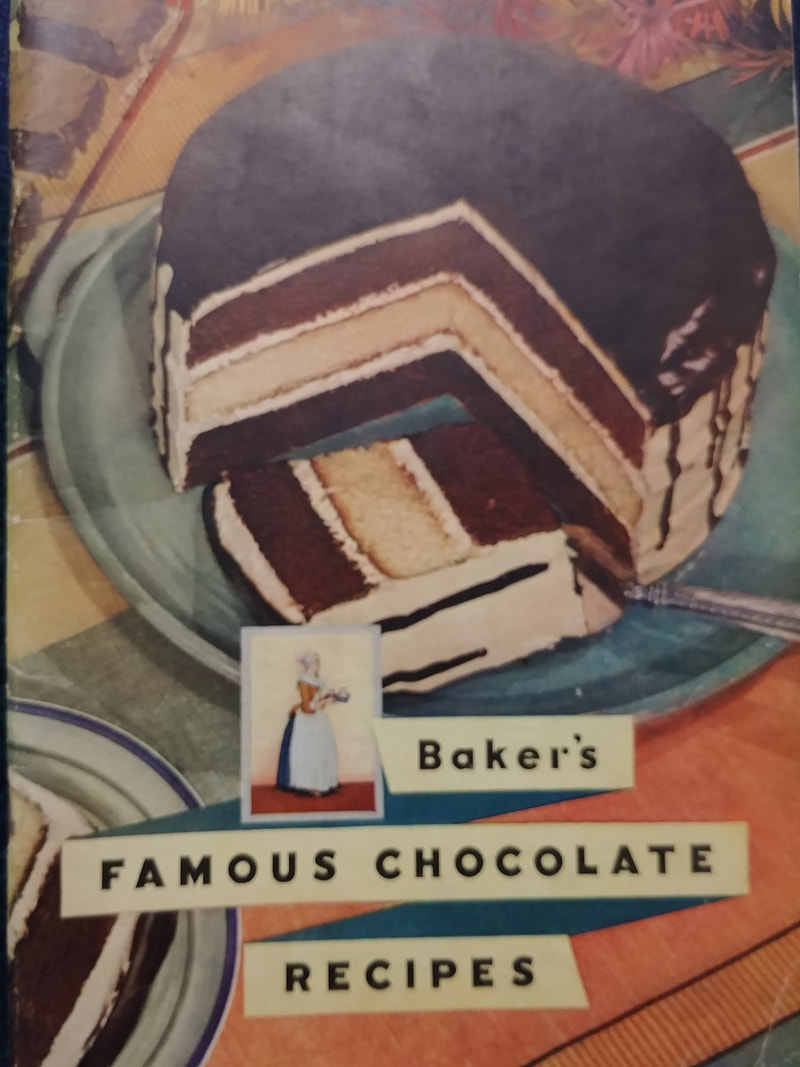

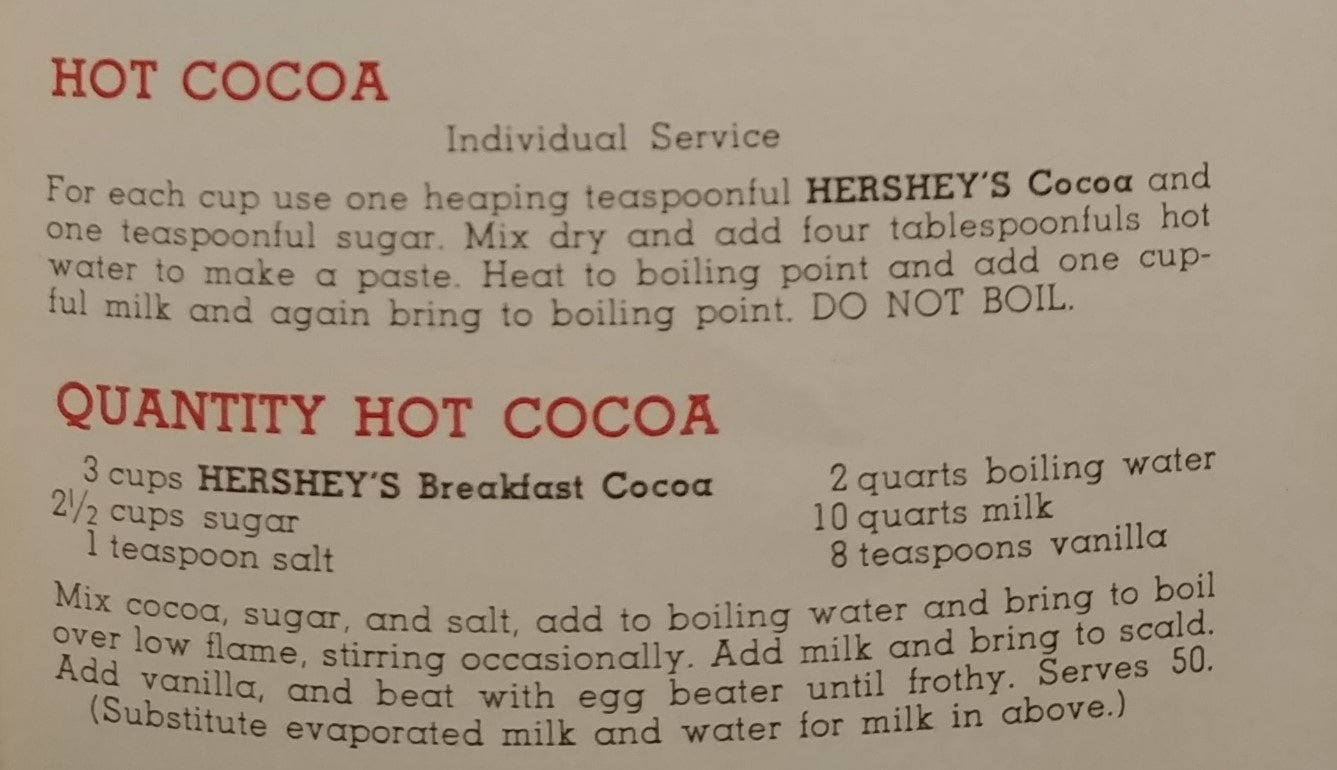

The Jemima CodeThe Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, Toni Tipton Martin. University of Texas Press, 2015. ISBN 0292745486. This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. If you want to know more about African American cookbooks, I recommend Toni Tipton Martin's The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. Although the information for each entry is sadly quite brief, it is nonetheless an important, enlightening, and beautifully produced catalog of all the known cookbooks authored by African Americans (real and fictional) in the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! In the United States, the terms "hot chocolate" and "hot cocoa" are used pretty interchangeably, but they aren't quite the same thing! Hot ChocolateHot chocolate is a truly ancient drink, dating back as many as 3000 years. Developed by ancient Indigenous people in Mesoamerica, the cacao bean was used by the Olmecs and drinking chocolate perfected by the Maya and Aztecs. A mixture of ground roasted cacao beans, spices, including chili peppers and vanilla, sometimes sweetened with honey, and often containing other ingredients, including ground maize and cochineal to color it red, early drinking chocolate was frothed into a foam and consumed as part of religious ceremonies. In the late 16th century, Spanish invaders had brought cocoa beans - and drinking chocolate - back to Spain, where it quickly spread throughout aristocratic Europe. It came to colonial America via Europe in the late 17th century, where cocoa processors started importing direct from Central America and the Caribbean. Hot chocolate became a fashionable breakfast beverage. But how was it made? Processed cocoa beans were fermented in the pulp, then dried, then roasted. Chopped into nibs, they were then stone ground to create a chocolate paste. Mixed with sugar, hot water, and spices, the bitter drink was served with cream and sugar, much like coffee or tea. By the 18th century, cakes of processed chocolate were being produced for transformation into drinking chocolate. In the mid-19th century, cocoa butter and sugar were added to the cacao and through conching and tempering, eating chocolate developed. By the Victorian period, hot chocolate had transformed from a popular adult beverage on par with coffee and tea, to the purview of children. Hot CocoaPart of the shift from breakfast beverage of aristocrats to children's treat had to do with the fact that both cacao and sugar were increasing in production and therefore dropping in price throughout the 19th century. Cocoa production expanded to other equatorial areas besides Mesoamerica and sugar, fueled by slavery and technological advances, also increased in production. The development of cocoa powder in the 1820s helped expand access to chocolate. Cocoa powder is created by melting or pressing the cocoa butter out of the nibs, then drying and grinding the defatted cocoa beans. Lighter weight, more shelf stable, and easier to blend into beverages than drinking chocolate, cocoa powder became the main ingredient in hot cocoa recipes. Most cocoa powder was natural process, like Hershey's, meaning that it was dried and ground after the Broma process of defatting. But some cocoa powders (like Fry's) were Dutched, or created using the Dutch process, which meant that the defatted cocoa nibs were immersed in an alkaline solution to help neutralize some of their natural acidity before being dried and ground. Natural cocoa is reddish brown in color - Dutch process color is a dark grayish brown. So there you have it! The difference between hot chocolate and hot cocoa is that one is made from melted cocoa, usually 100% cacao unsweetened chocolate, and hot cocoa is made from a mixture of cocoa powder and sugar, often cooked into a syrup. But how do you know which one you prefer? Hot chocolate or hot cocoa? Try these historic recipes and find out! Baker's Hot Chocolate Recipe (1936)I made this recipe as part of a talk on hot chocolate history, and while not very sweet, it is very rich and chocolatey. If you are a chocoholic, this is the recipe for you. Please note that you'll need Baker's Unsweetened 100% Cacao Chocolate, and that these days 2 squares is really 2 ounces, or 8 quarter ounce rectangles. 2 squares Baker's Unsweetened Chocolate 1 cup water 3 tablespoons sugar dash of salt 3 cups milk Add chocolate to water in top of double boiler and place over low flame, stirring until chocolate is melted and blended. Add sugar and salt and boil [over direct heat] 4 minutes, stirring constantly [this will boil off most of the water and make a thick syrupy chocolate]. Place over boiling water, add milk gradually, stirring constantly; then heat. Just before serving, beat with rotary egg beater until light and frothy. Serves 6. Hershey's Single Serve Hot Cocoa Recipe (1937)For each cup, use one heaping teaspoonful HERSHEY'S COCOA and one teaspoonful sugar [I used a heaping spoonful, which it needed]. Mix dry and add four tablespoons hot water to make a paste. Heat to boiling point and add one cupful milk and again bring to boiling point. DO NOT BOIL. You can use either natural process or Dutch process cocoa for this one. It is not as thick and rich as the Baker's hot chocolate, but it does have that familiar cocoa taste from childhood and is still quite good. You can always change these recipes to suit your tastes with more sugar or with half and half or part cream, instead of all milk. Top with whipped cream, marshmallows, or try your hand at Indigenous-inspired spices like chili powder, cinnamon, vanilla, etc. You can also substitute almond milk (the most historical substitution, since almond milk was known in 16th century Europe), or any other non-dairy milk. Which do you prefer, hot chocolate or hot cocoa? And how do you like yours prepared? I like mine extra-creamy with whipped cream. Maybe a little peppermint or salted caramel syrup if I'm feeling extra-indulgent. Share your perfect cup in the comments! These recipes are part of a talk with cooking demonstration on the history of hot chocolate I do for public events. For upcoming programs, visit my Event page. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 24 of the Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made eggnog and talked about all things Christmas, including Medieval beverages, the origins of fruitcake, plum pudding, and mincemeat. Full list of historic Christmas beverages below, and here's a little more history on the Eggnog Riot of 1826 at West Point! We also talked briefly about Charles Dickens (hence the Fezziwig image!) and the 2017 movie "The Man Who Invented Christmas," which I recommend!

(Apologies for the fuzzy audio - not sure what happened!)

A LOT of historic recipes for eggnog call for party-sized portions. But there are lots of single-serve versions in vintage bartender's guides through the ages. I thought we would use this one, Practical Bar Management, by Eddie Clark, published in 1954, which, co-incidentally, is also the same year the movie White Christmas came out. If you'd like to catch up with the menu I put together to go along with White Christmas, you can see all the blog posts and recipes here.

Eggnog (1954)

As you can tell, this recipe isn't exactly exact! Not even the spelling. Here's the original text:

"This drink can be made with either Brandy, Whisky, Rum, Gin, Sherry, or Port. "Pour into the shaker: 1 measure of the desired spirit or 1 wine glass of the chosen wine. Add the contents of 1 egg, 1 tablespoonful of sugar, 1/2 tumbler fresh milk. "Shake extra well and strain into a tall tumbler glass. Grate a little nutmeg on the drink before serving." Here's my adaptation, which I shook over ice to make it cold, which I think watered things down a smidge. Still very good. 1 jigger spiced rum 1 pony bourbon 1 large egg, well-washed 1/2 cup whole milk 1 tablespoon sugar Shake very well until cold and frothy. Grate some fresh nutmeg on top and serve cold. I am not generally a fan of prepared eggnog you can buy in stores. It's usually thickened with carageenan, VERY sweet, and very strongly flavored. This homemade version was much nicer - not as thick (although you could use half and half or light cream instead of milk for a richer product and skip the ice), not nearly as sweet, and although the alcohol was very forward (you could cut back a bit if you want), it was quite nice - creamy with a frothy head and didn't taste much like eggs at all, surprisingly. I'm a fan! Holiday Beverage Glossary

A LOT of different holiday beverages came up in the comments, so I thought I'd list a few with approximate ages and places of origin.

So what do you think? Did I miss any historic holiday beverages? At our house, we always serve an 18th century punch called Second Horse Punch. Which, like most Christmas classics, needs to be made in advance! Do you have any special or traditional holiday beverages? Share in the comments!

Food History Happy Hour and the Food Historian blog are supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

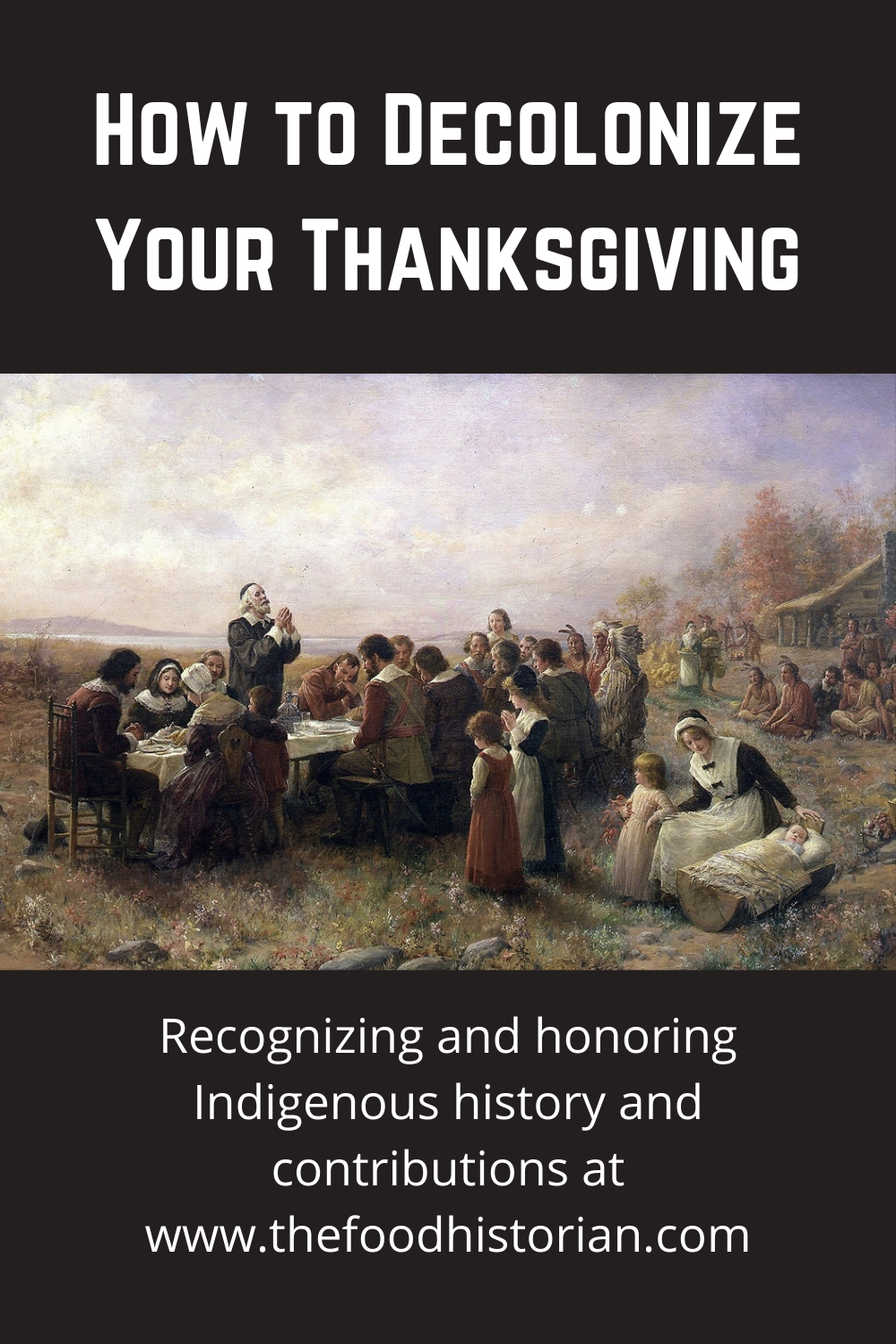

Think about the story of Thanksgiving you grew up with - Pilgrims in black clothes and funny hats and white aprons and shoes with big buckles sitting down to a Thanksgiving dinner with "the Indians," celebrating peace and harmony and the harvest. Maybe you made a construction paper turkey by tracing your hand. Maybe your teacher made Pilgrim hats and bonnets and "Indian headdresses." The focus was on the food and American exceptionalism. The real story is much, much different. "The First Thanksgiving," in 1621 was preceded and followed by violence. Indigenous voices and the role of the Wampanoag people in literally saving the lives of the English separatists (they didn't call themselves "Pilgrims") have been purposefully erased. The legacy of Indigenous foods - cultivated and created by Indigenous people - has also been largely erased from our cultural lexicon. So what can we do about it? This year, you can decolonize your Thanksgiving by learning the real history behind it and familiarizing yourself with the various Indigenous nations in your own backyard and who played an important role in American history. Today's blog post is essentially going to be a giant collection of articles to read and films to watch. I hope you take the time this weekend to read or watch a few with your family or friends and discuss (especially with your kids) the real story behind the myth. Mythbusting the First Thanksgiving What Really Happened at the 1st Thanksgiving from Voice of America What you learned about the ‘first Thanksgiving’ isn’t true. Here’s the real story - from USA Today via the Cape Cod Times The Real History Of The First Thanksgiving That You Didn’t Learn In School from All That Interesting Everything You Learned About Thanksgiving Is Wrong from the New York Times The Real History Of Thanksgiving Isn't The One You Learned In School—Here's How To Celebrate Smarter from Delish The Myths of the Thanksgiving Story and the Lasting Damage They Imbue from Smithsonian Magazine The true story behind Thanksgiving is a bloody one, and some people say it's time to cancel the holiday from Insider The Thanksgiving Myth Gets a Deeper Look This Year from the New York Times Meet the WampanoagMashpee Wampanoag Tribe The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, also known as the People of the First Light, has inhabited present day Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island for more than 12,000 years. After an arduous process lasting more than three decades, the Mashpee Wampanoag were re-acknowledged as a federally recognized tribe in 2007. In 2015, the federal government declared 150 acres of land in Mashpee and 170 acres of land in Taunton as the Tribe’s initial reservation, on which the Tribe can exercise its full tribal sovereignty rights. The Mashpee tribe currently has approximately 2,600 enrolled citizens. Learn more >>> Wampanoag History from the Wampanoag Nation 400 Years After the ‘First Thanksgiving,’ the Tribe That Fed the Pilgrims Continues to Fight for Its Land Amid Another Epidemic from Time Magazine In 1621, the Wampanoag Tribe Had Its Own Agenda from The Atlantic “OUR” STORY: 400 Years of Wampanoag History an online exhibit with short documentary films from Plymouth 400. U.S. Appeals Ruling In Mashpee Wampanoag Land Case from WBUR and the Cape Cod Times. Although the Mashpee Wampanoag won their case against the Department of the Interior, which had revoked their federal recognition, the US government is currently appealing that ruling. Hopefully that appeal process will cease in 2021. National Day of MourningThe National Day of Mourning was organized in 1970 in response to a specific event of the suppression of history. This is the 50th anniversary of that event. Here's some background on what led to the creation of the National Day of Mourning from the United American Indians of New England: "In 1970, United American Indians of New England declared US Thanksgiving Day a National Day of Mourning. This came about as a result of the suppression of the truth. Wamsutta, an Aquinnah Wampanoag man, had been asked to speak at a fancy Commonwealth of Massachusetts banquet celebrating the 350th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims. He agreed. The organizers of the dinner, using as a pretext the need to prepare a press release, asked for a copy of the speech he planned to deliver. He agreed. Within days Wamsutta was told by a representative of the Department of Commerce and Development that he would not be allowed to give the speech. The reason given was due to the fact that, "...the theme of the anniversary celebration is brotherhood and anything inflammatory would have been out of place." What they were really saying was that in this society, the truth is out of place. "What was it about the speech that got those officials so upset? Wamsutta used as a basis for his remarks one of their own history books - a Pilgrim's account of their first year on Indian land. The book tells of the opening of my ancestor's graves, taking our wheat and bean supplies, and of the selling of my ancestors as slaves for 220 shillings each. Wamsutta was going to tell the truth, but the truth was out of place. "Here is the truth: "The reason they talk about the pilgrims and not an earlier English-speaking colony, Jamestown, is that in Jamestown the circumstances were way too ugly to hold up as an effective national myth. For example, the white settlers in Jamestown turned to cannibalism to survive. Not a very nice story to tell the kids in school. The pilgrims did not find an empty land any more than Columbus "discovered" anything. Every inch of this land is Indian land. The pilgrims (who did not even call themselves pilgrims) did not come here seeking religious freedom; they already had that in Holland. They came here as part of a commercial venture. They introduced sexism, racism, anti-lesbian and gay bigotry, jails, and the class system to these shores. One of the very first things they did when they arrived on Cape Cod -- before they even made it to Plymouth -- was to rob Wampanoag graves at Corn Hill and steal as much of the Indians' winter provisions as they were able to carry. They were no better than any other group of Europeans when it came to their treatment of the Indigenous peoples here. And no, they did not even land at that sacred shrine down the hill called Plymouth Rock, a monument to racism and oppression which we are proud to say we buried in 1995. "The first official "Day of Thanksgiving" was proclaimed in 1637 by Governor Winthrop. He did so to celebrate the safe return of men from Massachusetts who had gone to Mystic, Connecticut to participate in the massacre of over 700 Pequot women, children, and men. "About the only true thing in the whole mythology is that these pitiful European strangers would not have survived their first several years in "New England" were it not for the aid of Wampanoag people. What Native people got in return for this help was genocide, theft of our lands, and never-ending repression. "But back in 1970, the organizers of the fancy state dinner told Wamsutta he could not speak that truth. They would let him speak only if he agreed to deliver a speech that they would provide. Wamsutta refused to have words put into his mouth. Instead of speaking at the dinner, he and many hundreds of other Native people and our supporters from throughout the Americas gathered in Plymouth and observed the first National Day of Mourning. United American Indians of New England have returned to Plymouth every year since to demonstrate against the Pilgrim mythology. "On that first Day of Mourning back in 1970, Plymouth Rock was buried not once, but twice. The Mayflower was boarded and the Union Jack was torn from the mast and replaced with the flag that had flown over liberated Alcatraz Island. The roots of National Day of Mourning have always been firmly embedded in the soil of militant protest." You can learn more about the United American Indians of New England and their mission and watch a livestream of their National Day of Mourning program live from Plymouth here: http://www.uaine.org/ Not all Native Americans celebrate Thanksgiving. Find out why. from the Cape Cod Times. For Native Peoples, Thanksgiving Isn't A Celebration. It's A National Day Of Mourning from WBUR 400 Years After First Thanksgiving, Native Americans Honor 'Day of Mourning' Instead from Newsweek Indigenous Foods & Thanksgiving DinnerYou may recall my catalog of Indigenous foods a few weeks ago. The global impact of Indigenous agriculturalists is a staggering and often overlooked or ignored part of our history. Here are some books, films, and articles you can read to learn more about the impact of Indigenous food on our diet and the struggles of Indigenous chefs and historians to reclaim their food sovereignty. Indigenous Chefs On Traditional Cooking And Their Complicated Relationship With Thanksgiving from Delish Native Americans want to decolonize Thanksgiving with native foods and a proper history lesson KIRO radio Sean Sherman, The Sioux Chef: ‘This Is The Year To Rethink Thanksgiving’ from the Huffington Post This Thanksgiving, Make These Native Recipes From Indigenous Chefs from the Huffington Post 3 Indigenous Chefs Talk About What Thanksgiving Means to Them from Bon Appetit This Thanksgiving, try these recipes for local Native American foods from Kansas City Magazine How to Decolonize Your Thanksgiving Dinner by Vice “We are still alive”: How Native communities grapple with Thanksgiving’s colonial legacy from The Counter Films to Watch this ThanksgivingI cannot recommend the film Gather enough. You can rent it on Vimeo, Amazon Prime, or check their website for free screenings. It's stunningly filmed, it portrays a huge variety of Indigenous voices and stories, and it tells an amazing story of the effort of Indigenous people to reclaim their food sovereignty. Sean Sherman, also known as the Sioux Chef, has done a lot to bring national attention to Indigenous foodways. He's written a book and you can learn more about him on his website. Andi Murphy is the host of the Toasted Sister Podcast: Radio about Native American Food. Well folks if I want to get this done before midnight on Thanksgiving I have to stop, but stay tuned for another post on Indigenous Food Historians You Should Know, which I hope to get up soon. Featuring all kinds of amazing people, stories, books, and even more documentary films. I hope this collection of resources has helped you re-learn your American history and decolonize your Thanksgiving this and every year. As always, The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!