|

The Food and Drug Administration recently announced that it would be de-regulating French Dressing. And while people have certainly questioned why we A) regulated French Dressing in the first place and B) are bothering to de-regulate it now, much of the real story behind this de-regulation is being lost, and it's intimately tied to the history of French Dressing.

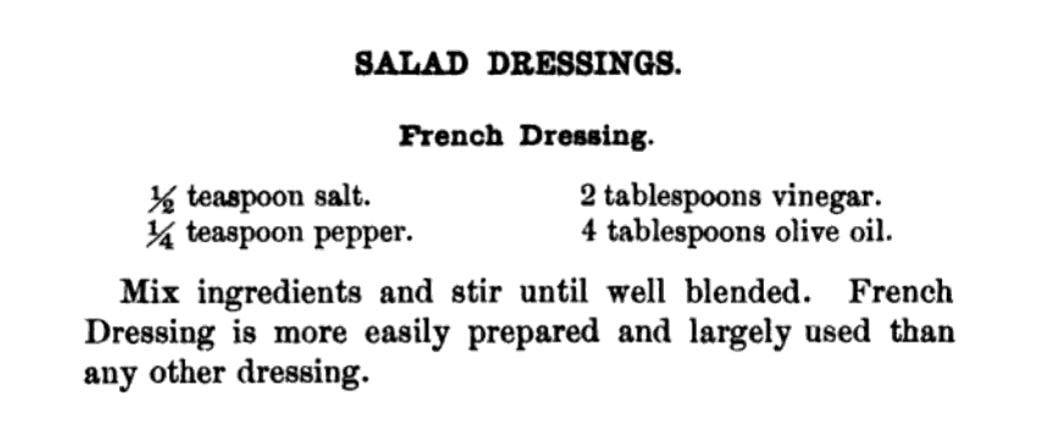

A lot of people like to claim that French Dressing is not actually French. And if you're defining French Dressing as the tangy, gloppy, red stuff pretty much no one makes from scratch anymore, you'd be right. But the devil is in the details, and even the New York Times has missed this little bit of nuance. This Times article, published before the final de-regulation went into place, notes, "The lengthy and legalistic regulations for French dressing require that it contain vegetable oil and an acid, like vinegar or lemon or lime juice. It also lists other ingredients that are acceptable but not required, such as salt, spices and tomato paste." (emphasis mine) What's that? The original definition of French Dressing, according to the FDA, was essentially a vinaigrette? What could be more French than that? In fact, that is, indeed, how "French dressing" was defined for decades. Look at any cookbook published before 1960 and nearly every reference to "French dressing" will mean vinaigrette. Many a vintage food enthusiast has been tripped up by this confusion, but it's our use of the term that has changed, not the dressing. Take, for instance, our old friend Fannie Farmer. In her 1896 Boston Cooking School Cookbook (the first and original Fannie Farmer Cookbook), the section on Salad Dressings begins with French Dressing, which calls for simply oil, vinegar, salt, and pepper.

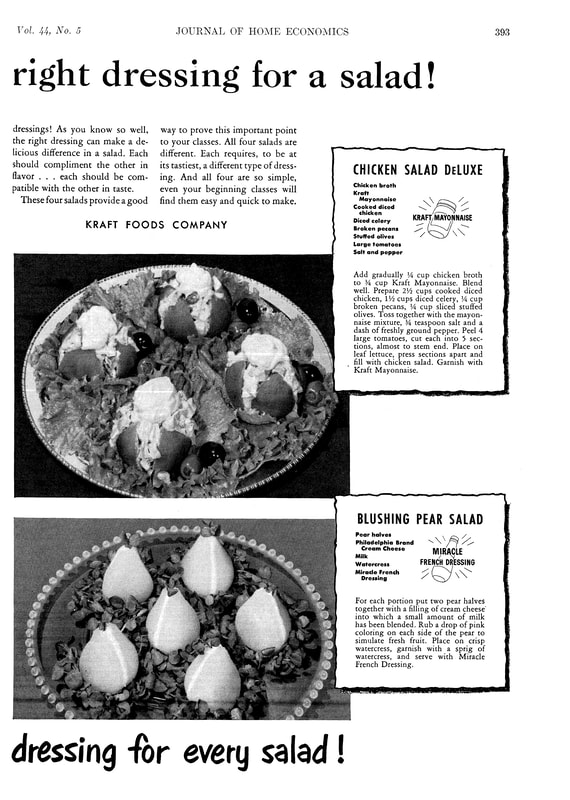

She's not the only one. I've found references in hundreds of cookbooks up until the 1950s and '60s and even a few in the 1970s where "French dressing" continued to mean vinaigrette. You can usually tell by the recipe - composed salads of vegetables are the most common. If a recipe for "French dressing" is not included, and no brand name is mentioned, it's almost certainly a vinaigrette. So what happened?

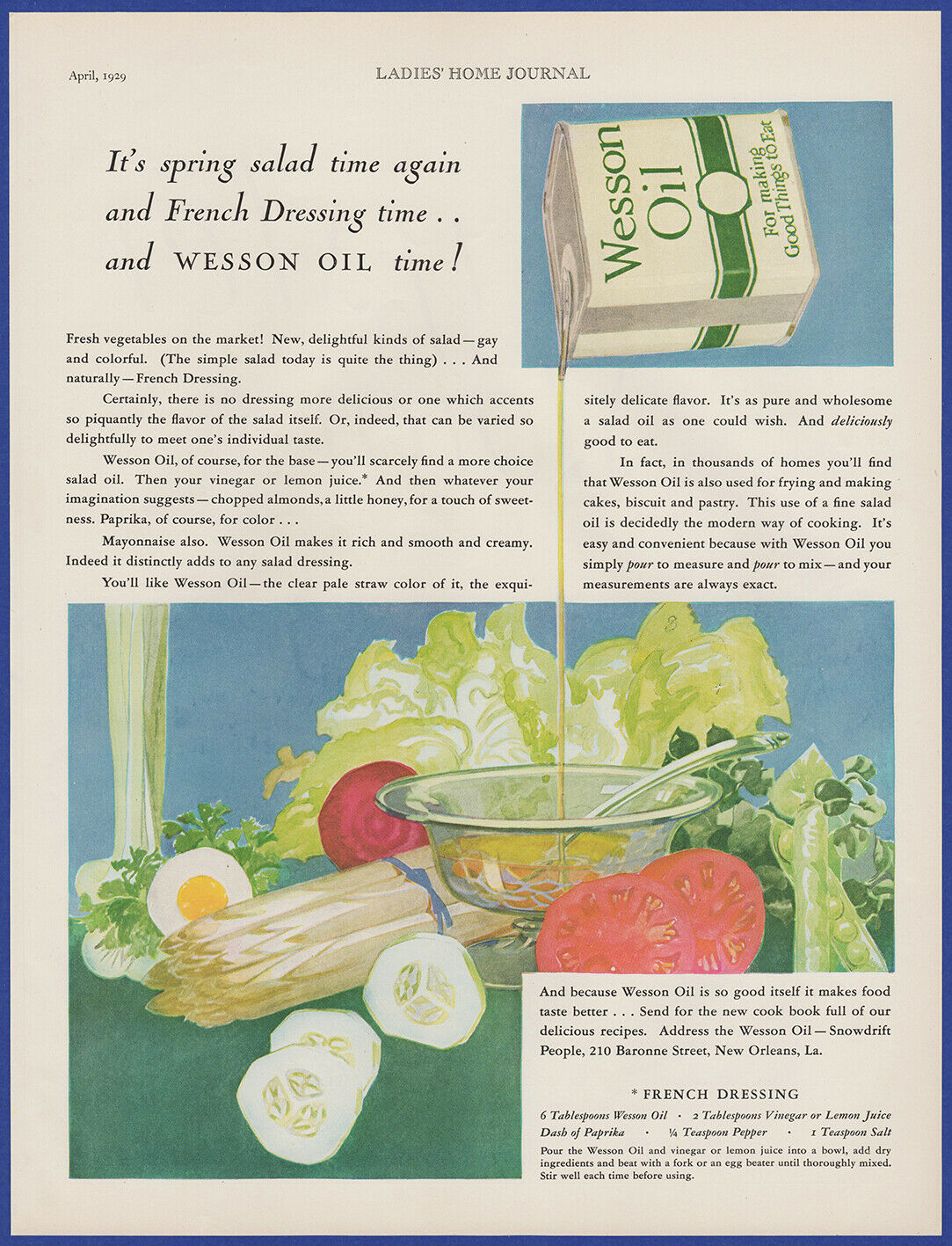

I've managed to track down the original 1950 FDA Standard of Identity for mayonnaise, French dressing, and salad dressing. In it, the three condiments are considered together and are the only dressings identified, likely because few if any other dressings were being commercially produced. Although the term "salad dressing" has been extremely confusing to many modern journalists, it is clearly noted in the 1950 standard of identity of being a semi-solid dressing with a cooked component - in short, boiled dressing. The closest most Americans get today is "Miracle Whip," which is, in fact, a combination of mayonnaise and boiled dressing. Generic brands are often called just "salad dressing" because it was often used to bind together salads like chicken, egg, crab, and ham salad, and also often used with coleslaw. So it makes perfect sense that "French dressing" would be the designated term for poured dressings designed to be eaten with cold lettuce and vegetables - i.e. what we consider salad today. People have wondered why we needed to regulate salad dressings, but there is one very important distinction in the 1950 rule - it prohibits the use of mineral oil in all three. Mineral oil, which is a non-digestible petroleum product (i.e. it has a laxative effect), and which is colorless and odorless, was a popular substitute for vegetable oil during World War II by dieters in the mid-20th century. I collect vintage diet cookbooks and it shows up frequently in early 20th century ones, especially as a substitute for salad dressings. Mineral oil is also extremely cheap when compared with vegetable oils, and it would be easy for unscrupulous food manufacturers to use it to replace the edible stuff, so the FDA was right to ensure that it did not end up in peoples' food. Mineral oil is sometimes still used today as an over-the-counter laxative, but can have serious health complications if aspirated. There were several subsequent addenda to the standard of identity, but most were about the inclusion of artificial ingredients or thickeners, with no mention of any ingredients that might change the flavor or context of what was essentially a regulation for vinaigrette until 1974, when the discussion centered around the use of artificial colors instead of paprika to change the color of the dressing. The FDA ruled that "French dressing may contain any safe and suitable color additives that will impart the color traditionally expected." So here we see that by the 1970s, the standard of identity hadn't actually changed much, but the terminology had. "French dressing" went from the name of any vinaigrette, to a specific style of salad dressing containing paprika (and/or tomato). When people started adding paprika is unclear, but it was probably sometime around the turn of the 20th century, when home economists began to put more and more emphasis on presentation and color. A lively reddish orange dressing was probably preferable to a nearly-clear one. In 2000, the LA Times made an admirable effort to track the early 20th century chronology of the orange recipes. By the 1920s, leafy and fruit salads began to overtake the heavier mayonnaise and boiled dressing combinations of meat and nuts. As the willowy figure of the Gibson Girl gave way to the boyish silhouette of the flapper, women were increasingly concerned about their weight, and salads were seen as an elegant solution.

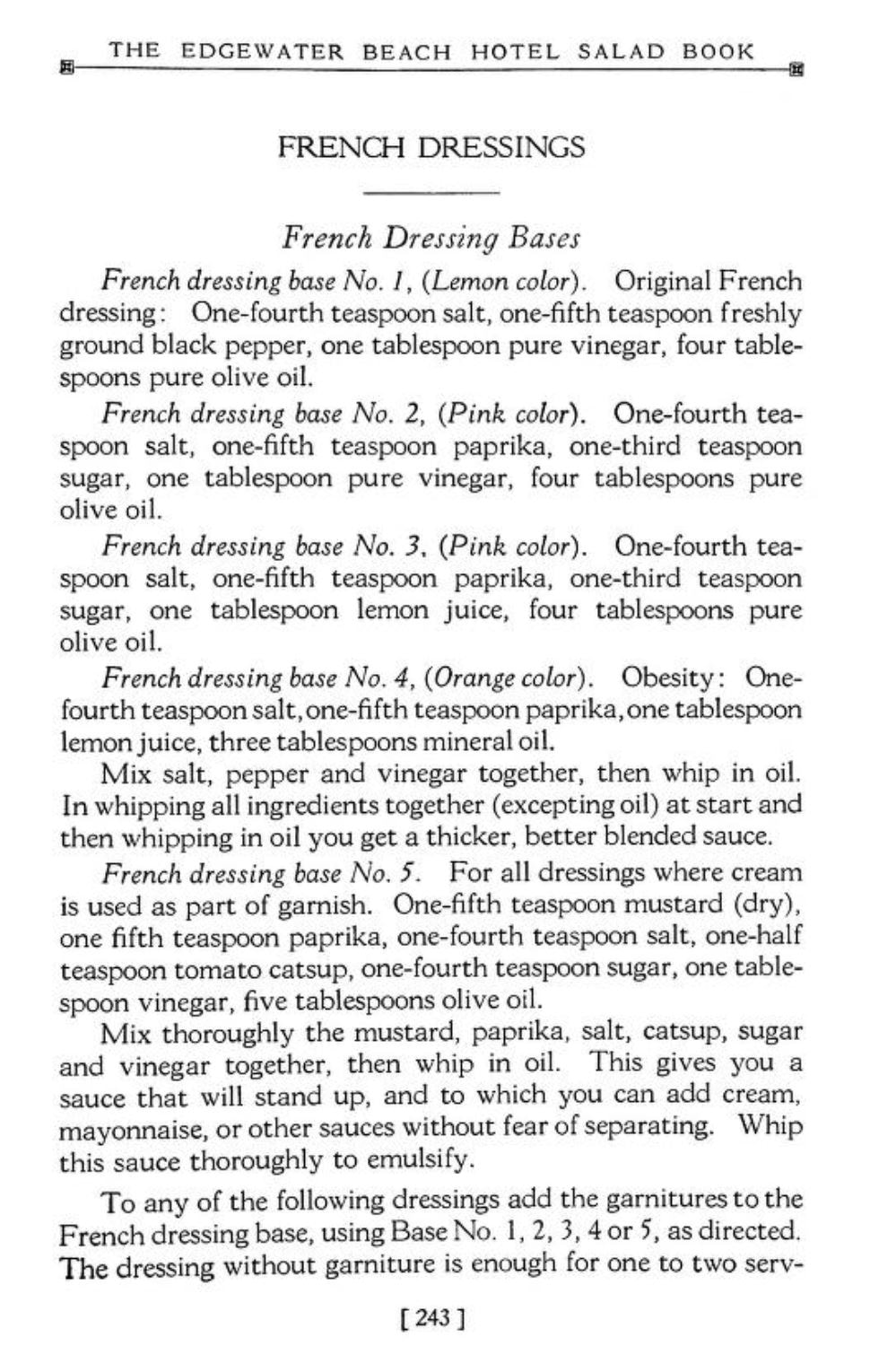

The recipes pictured above are from The Edgewater Beach Hotel Salad Book, published in 1928 (Patreon patrons already got a preview of this cookbook earlier in the week!). The Edgewater Beach Hotel was a fashionable resort on the Chicago waterfront which became known for its catering and restaurant, and in particular its elegant salads. You'll note that several French Dressing recipes are outlined (they are also introduced first in the book), and are organized by color. "No. 4 (Orange Color)" has the note "obesity" not because it would make you fat - quite the opposite - its use of mineral oil was designed for people on diets. Although the fifth recipe does not note a color, it does contain both paprika and tomato "catsup," and all but the original and "obesity" recipes contain sugar. An increase in the consumption of sweets in the early 20th century is often attributed to the Temperance movement and later Prohibition.

By the 1950s, recipes for "French Dressing" that doctored up the original vinaigrette with paprika, chili sauce, tomato ketchup, and even tomato soup abounded. My 1956 edition of The Joy Of Cooking has over three pages of variations on French Dressing. Hilariously, it also includes a "Vinaigrette Dressing or Sauce," which is essentially the oil and vinegar mixture, but with additions of finely chopped pimento, cucumber pickle, green pepper, parsley, and chives or onion, to be served either cold or hot. All the other vinaigrettes have the moniker "French dressing." A Google Books search reveals an undated but aptly titled "Random Recipes," which seems to date from approximately mid-century, and which includes a recipe for Tomato French Dressing calling for the use of Campbell's tomato soup, and "Florida 'French Dressing'," containing minute amounts of paprika, but generous citrus juices and a hint of sugar. So maybe people were making their own sweetly orange French dressing at home after all?

There is some debate as to who actually "invented" the orange stuff, but while Teresa Marzetti may have helped popularize it, the general consensus is the Milani brand, which started selling its orange take in 1938 (or the 1920s, depending who you ask - I haven't found a definitive answer one way or the other), was the first to commercially produce it. Confusingly, the official Milani name for their dressing is "1890 French Dressing." The internet has revealed no clues as to whether or not the recipe actually dates back that far, but a 1947 New York Times article claims "On the shelves at Gimbels you'll find 1890 French dressing, manufactured by Louis Milani Foods. It is made, the company says, according to a recipe that originated in Paris at that time and was brought to this country after the fall of France. This slightly sweet preparation, which contains a generous amount of tomatoes, costs 29 cents for eight ounces." This seems like a marketing ploy rather than the truth, but who knows for sure?

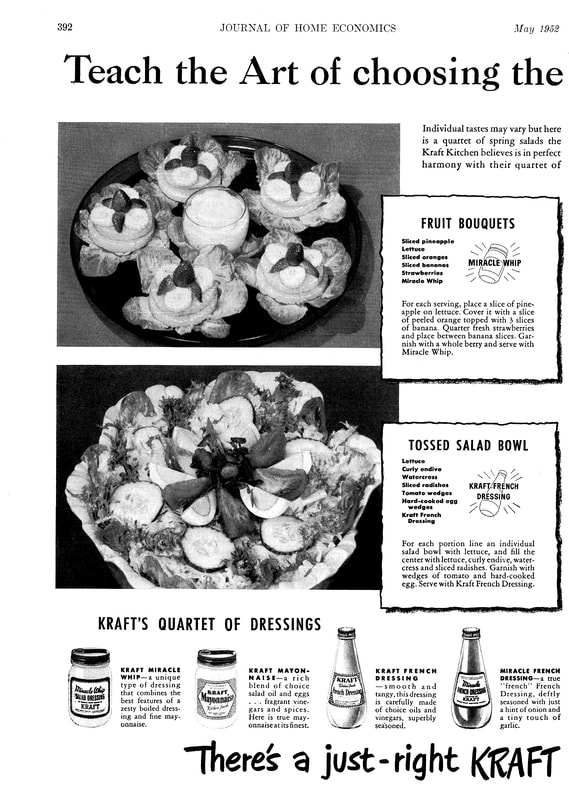

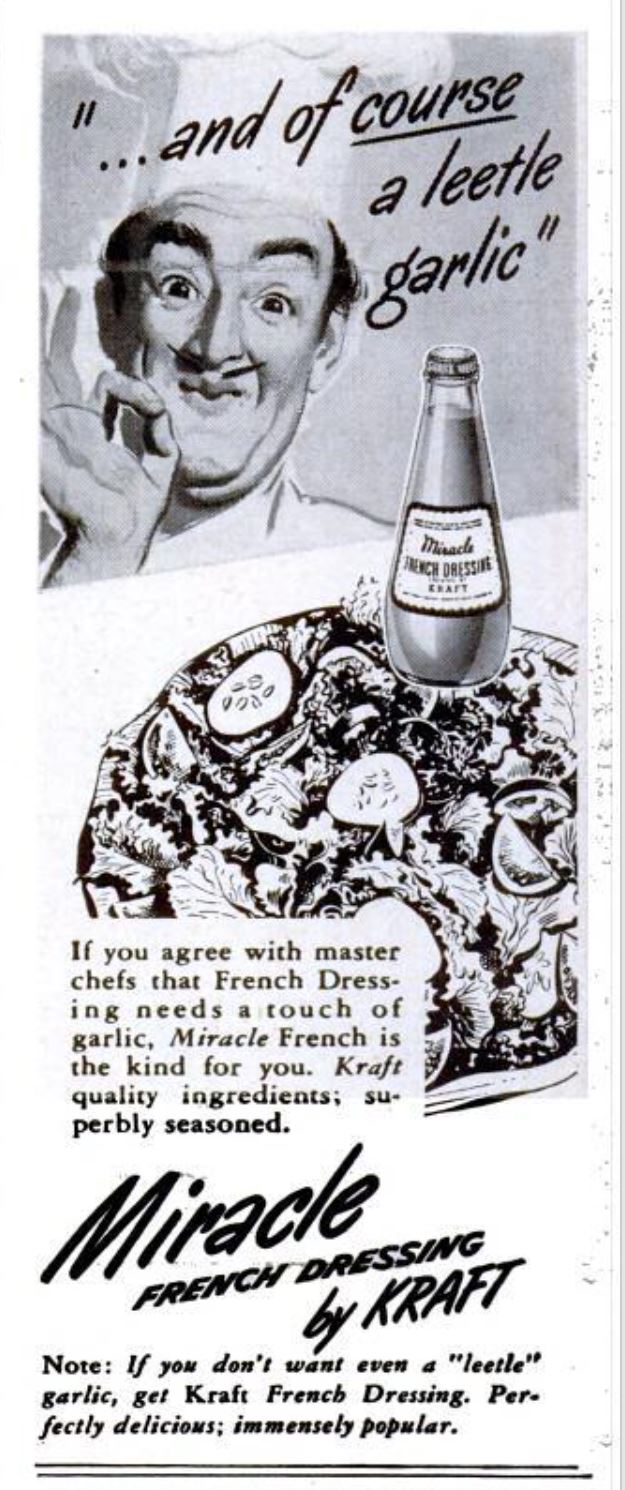

In 1925, the Kraft Cheese Company did sign a contract with the Milani Company to become their exclusive distributor. At least, that's what a snippet view of 1928 New York Stock Exchange listing statements tells me. As early as 1931 Kraft was manufacturing French Dressing under their name, and by the 1940s it had also used the Miracle Whip brand name to create Miracle French Dressing - which had just a "leetle" hint of garlic.

One snippet reference in the 1934 edition of "The Glass Packer" notes, "Differing from Kraft French Dressing, Miracle French is a thin dressing in which the oil and vinegar separate in the bottle, and which must be shaken immediately before using." Miracle French was contrasted often in advertising with classic Kraft French as being zestier, which may have led to the development in the 1960s of Kraft's Catalina dressing, a thinner, spicier, orange-er French dressing.

In fact, as featured in this undated magazine advertisement, Kraft at one point had several varieties of French Dressing including actual vinaigrettes like "Oil & Vinegar," and "Kraft Italian" alongside Catalina, Miracle French, Casino, Creamy Kraft French, and Low Calorie dressing, which also looks like French dressing. What you may notice is that the "Creamy Kraft French" looks suspiciously like most of the gloppy orange stuff you see on shelves today, and which generally doesn't resemble a thin, runny, paprika/tomato-red dressing that dominates the rest of this lineup.

"Spicy" Catalina dressing was likely introduced sometime around 1960 (although the name wasn't trademarked until 1962). Kraft Casino dressing (even more garlicky) was trademarked for both cheese and French dressing in 1951, but by the 1970s appears to have left the lineup. Here are a few fun advertisements that compare some of the Kraft French dressings:

Of course by the 1950s other dressing manufacturers besides Kraft were getting in on the salad dressing game, including modern holdouts like:

Although many people in the United States grew up eating the creamy orange version of French Dressing, it's mostly vilified today (aside from a few enthusiasts). Which is too bad. As a dyed-in-the-wool ranch lover (hello, Midwestern upbringing - have you tried ranch on pizza?), I try not to judge peoples' food preferences. And I have to admit that while I've come to enjoy homemade Thousand Island dressing, I can't say that I've ever actually had the orange French! Of any stripe, creamy, spicy, or otherwise. I'm much more likely to use homemade vinaigrette from everything from lentil, bean, and potato salads to leafy greens. So to that end, let's close with a little poll. Now that you know the history of French Dressing, do you have a favorite? Tell us why in the comments!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

1 Comment

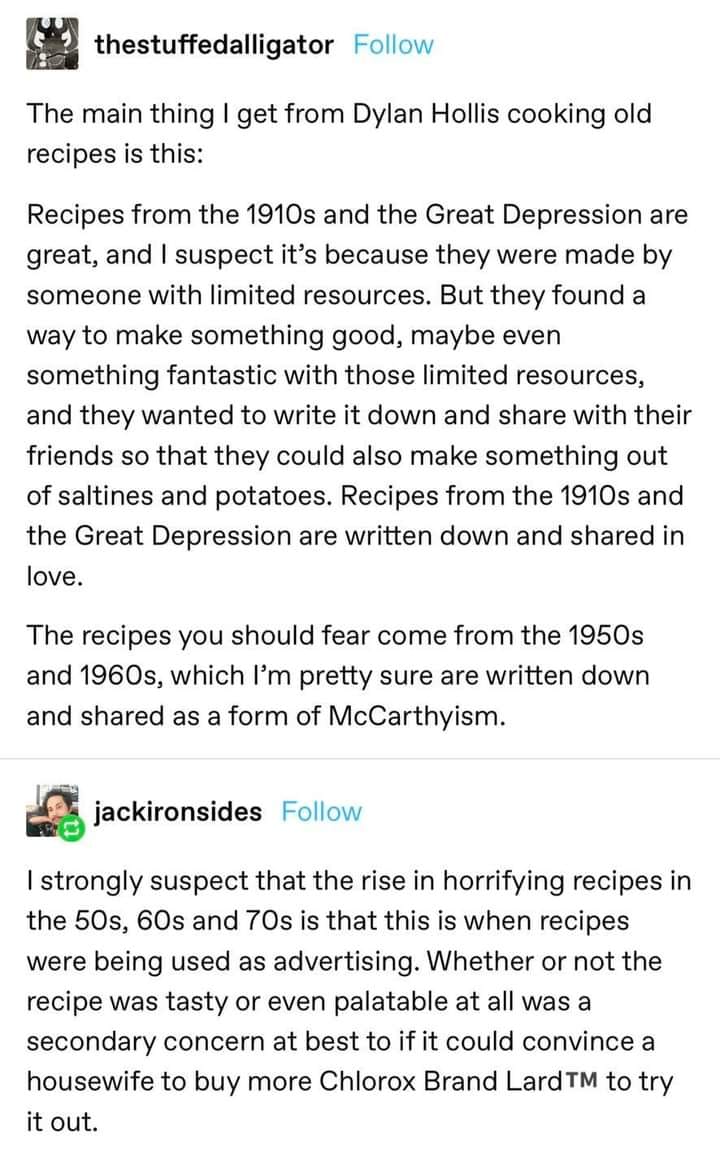

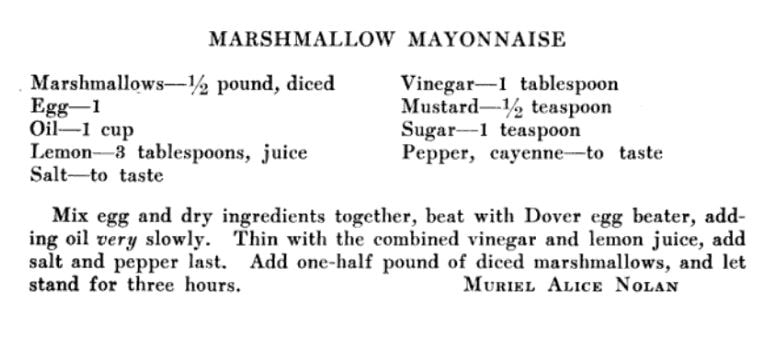

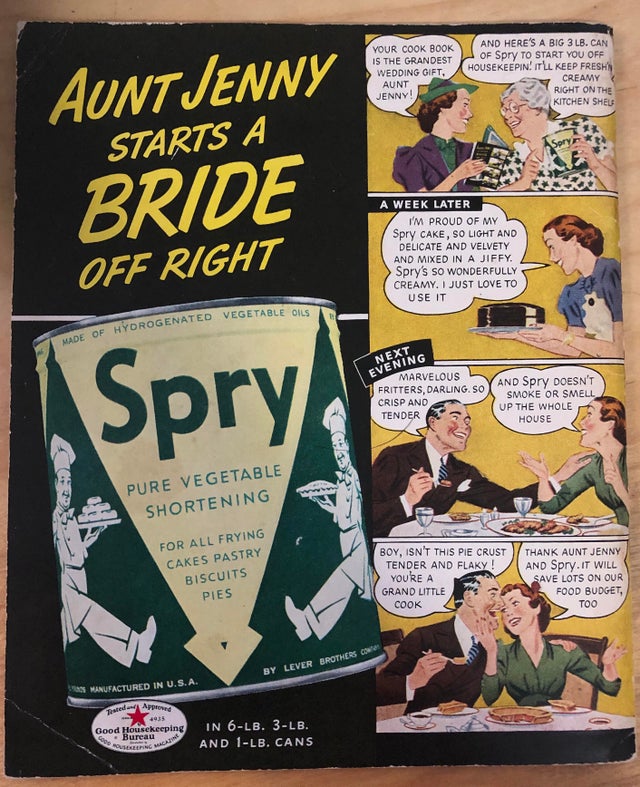

Well friends, I said I was contemplating a part two to last week's examination of 1950s food, and this meme kept popping up on my socials, so here we are again! This one isn't quite as inflammatory, and no fun illustration to catch your eye, but it makes a similar claim nonetheless. Here's the original text: The main thing I get from Dylan Hollis cooking old recipes is this: If you haven't seen any of Dylan Hollis' TikTok videos, I recommend them! He's hilarious. Not a food historian, but he cooks historic recipes and taste tests them. Some are horrific, but most are delicious - and while Dylan's reactions are 99% of the fun, his shock when things are actually tasty, while hilarious, does grate a little sometimes. Yes, people in the past really did know what they were doing! The meme claims that the food of the 1910s and the Great Depression were better than the 1950s, and were made with love, working with limited ingredients, whereas 1950s recipes were made to sell products during the McCarthy era. And while those ideas aren't necessarily wrong, they're definitely not the whole story. The time period of 1900 to 1950 is my favorite time period for cookbooks. They usually have decent instructions with things like measurements and oven temperatures, but are still from scratch. USUALLY being the key word there. Because starting in the 1870s, corporate food brands started publishing cookbooklets to sell their products. One of the earliest adopters of this sales tactic? Cottolene brand shortening. Not exactly lard, but pretty darn close! A lot of the corporate cookbooks and cookbooklets of the late 19th and early 20th century were primarily for ingredients. Different brands of flavorings and spices, baking powder, flour, shortening or lard, etc. were the main branded food products at the time. A lot of major food companies today started out as flour companies, including General Mills. So the cookbooks were largely normal scratch recipes that just recommended the cook or baker use the branded ingredients, but it was easy to substitute whatever you had on hand. And then, we started to get corporate food products like Campbell's canned soups, and Libby's canned corned beef, and powdered Knox gelatine and Jell-O, and other foods that were closer to finished foods already. You can only eat so much soup in a week. So how was Campbell's to get people to eat more of it? In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we had more and more women graduating from food and nutrition schools and college programs. Domestic scientists and expert cooks and home economists happily filled the role of cookbook authors and test kitchen managers for food corporations. Which is how we got things like tomato soup spice cake (Dylan Hollis does a recipe from the 1950s, but it was actually invented in the 1920s!), cream of whatever soup casseroles, and marshmallow mayonnaise. While tomato soup spice cake is probably delicious (at least, Dylan Hollis thinks it is!), and cream of whatever soup is a lot easier than white sauce, I'm not sure about the marshmallow mayonnaise, but the cookbook says to serve it with fruit salad, so maybe it is? Who am I to judge? The point being, by the 1910s, there were plenty of marketing cookbooks and advertisements with recipes for processed foods for housewives to choose from. And while home economists were cranking out recipes that were sometimes smash hits and sometimes abject failures, there was a bit of a storm brewing in households around the country. Mainly, the "servant problem." For most of the 19th century, middle and upper-middle class families had at least one household servant (or enslaved person, prior to the Civil War) who did the bulk of the heaviest household labor. Middle class women and their daughters did household work too, but were generally spared things like scouring pots and scrubbing floors and hauling water and coal. But at the turn of the 20th century, we started to get pink collar jobs - being a shop girl or secretary or teacher or nurse was preferable for many women to the 24/6.5 schedules of being in service. Rural families usually had lots of children to help with agricultural labor, but in a family of 6 or 10, the older girls always helped care for the younger children and everyone did household chores. As families shrunk and household servants became harder to find and more expensive, more and more women had to do with less and less help at home. At the same time, education levels for women were rising. Girls stayed in school beyond the elementary level and attended high school and college in larger and larger numbers. Many parents also wanted better lives for their children than they had, and wanted to spare girls the drudgery of household labor. Upper and upper-middle class girls, in particular, had been raised in households with servants and mothers who spared them all but the basics of running a household. So when they married, all of a sudden girls with college educations had to figure out household budgets and weekly grocery shopping and cooking on their own, without many skills or resources to help them. Enter the ad man and the home economist. Swearing to save the clueless young bride from a lifetime of drudgery, while still pleasing her husband, all sorts of companies targeted young, inexperienced women just starting their households, but none perhaps as diligently as Spry, which manufactured first lard and later shortening (there's that lard reference again!). Aunt Jenny was the fictional grandmotherly character who knew just everything and would teach it all to her clueless niece. And of course, the secret was always a giant can of Spry. While Spry cookbooklets joined the legion of competitors, it was their cartoon-style print ads and extensive radio shows and advertisements that helped sway millions of American women to the Spry way of life. Is it any wonder that women who married in the 1930s and '40s raised children in the 1950s on corporate foods? Untrained, without the household help of their mothers and grandmothers, and with high expectations for home cleanliness and cooking three meals a day, 364 days a year would be enough to drive anyone into the arms of kindly home economists and fictional characters like Aunt Jenny, Mary Lee Taylor, Betty Crocker, and others. Recipes as advertisements for corporate foods did NOT start in the 1950s by any means. But the meme is somewhat correct in that scratch cooking was more prevalent in the Great Depression in particular, largely because at the time industrial foods were still more expensive than cooking from scratch, and because women who were adults in the 1930s were more likely to have been born into households that still taught them something about cooking and household management. And although the balance of population in the United States tipped from rural to urban in the 1920s, we still had a huge population of people primarily involved in agriculture, meaning families were larger (my mom's parents, born to farmers in the 1930s, came from families of 9 and 10 children, respectively), so women had more household help. Rural areas were also slower to adopt new fashions, including fashionable food, and often had less access to industrial goods of all sorts, including processed foods. Rural families were also much more likely to grow and preserve the bulk of their own food, well into the 1970s, than the rest of America. If you had land and free labor, it was certainly cheaper than buying commercially canned goods. If your grandmother grew up in a rural area during the Great Depression, like mine did, she probably learned how to cook from scratch. But by the 1950s, she was raising kids on her own, and maybe had a career of her own, or was supporting her husband's career, which meant less time to cook from scratch as she cared for her own children and a house with higher standards of cleanliness and fashion than her mother's with a lot less help. At the same time, in the 1950s, the general consensus was that industrial foods were the wave of the future - they were boons to help a busy housewife, not things to be scorned and rejected. And as incomes rose, it was much easier to purchase foods than doing your own home preserving. And while the Great Depression did result in a lot of creative cooks (banana bread, for instance), I find the mention in the original meme of Saltines ironic. Although Saltines and cracker companies like Ritz didn't invent cracker-based mock apple pie (that dates back to the 1850s, believe it or not), they sure hopped right on that bandwagon and used it as a selling point. Necessity is the mother of invention. But rising incomes are the mother of convenience. And while McCarthyism probably did prevent the spread of some delicious and interesting foodways through its xenophobia and rigid conformity, the road to corporate convenience foods was a long one. They didn't appear overnight once the calendar ticked over from 1949 to 1950. Indeed, scratch cooking and baking continued well into the 1950s, and many of the foods we associate with the 1950s (Cool Whip, anyone?) weren't actually invented until the 1960s. For instance, the Pillsbury Bake-Off baking contest didn't start until 1949, and while modern incarnations of the contest are usually dominated by mutated versions of whatever convenience food Pillsbury has cooked up (usually crescent rolls or cinnamon rolls or canned biscuits), the original contest was meant to promote Pillsbury flour, so the recipes are all from scratch. And looking at my food historian library shelves, the 1950s section has plenty of community cookbooks filled with can-of-this, box-of-that recipes, and advertising cookbooklets galore, but there are also cookbooks like The Magic in Herbs (first printed in 1941 but on its seventh printing by my 1950 copy) and The Peasant Cookbook (1955, and my copy was from the library of the Ladies' Home Journal!), and Whole Grain Cookery (1951) and those community cookbooks always had scratch recipes in them, too. And my 1930s section? I have more corporate cookbooklets from the 1930s than any other era! Like most of history, individual decades might be changed and marked by big events, but history is complicated. In the Progressive Era we had brutal strikes and food riots, but we also had Gibson Girls and Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. During the Great Depression we had the Dust Bowl and migrant workers, but we also had the glamour of Hollywood. And yes, in the 1950s we had McCarthyism (and sexism and racism) and processed food, but we also had folks like James Beard and Julia Child and plenty of scratch cooking. So let's stop stereotyping decades and accept them for what they are - complicated, messy, and fascinating time periods with both good food and bad. And the next time you see a corporate food cookbook from the 1950s - give it a gander. You might be surprised by what you find inside. There are good recipes in just about every cookbook, if you take the time to look. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! There's this weird trend in modern America where we love to mock the foods of the 1950s (and, to a lesser extent, the 1960s and '70s). Everyone from James Lileks (here and here) to Buzzfeed-style listicles to internet memelords have weighed in on how terrible food was in the 1950s. But was it? Was it really? Or are we just expressing bias (conscious or not) about foods we haven't tried and don't understand? I have seen this meme all over my social feeds lately. Including, regrettably, in some food history and food studies groups. Some clever memer stole an image from Midcentury Menu (which is a delightful blog, please check out Ruth's work) and added their own commentary. The author of the meme is unclear, but it appears to have been posted about a week ago. Whenever I challenge the idea that maybe 1950s foods aren't nearly as bad as we think they are, I often get accused of engaging in nostalgia (spoiler alert, I was born in the 1980s) or romanticizing the past, usually accompanied by an assertion that these foods are "objectively" bad. But I can't help but thinking of how our concepts of disgust are much more a product of the society and time period we were brought up in, than anything resembling objectivity. The New York Times Magazine just published an article about the science of disgust earlier this week, but what I find interesting about the article is how many of the examples centered on food, and yet how little food is actually discussed. Indeed, almost all of the science of disgust seems focused entirely on evolutionary factors, such as protecting us from spoiled foods, from acquiring diseases from bodily fluids and corpses, or from weakening our gene pool through incest. Very few people outside of the food world discuss the cultural reasons behind disgust that have nothing to do with biology and everything to do with cultural, racial, religious, and ethnic factors. Earlier this year The New Yorker published a piece by Jiayang Fan on the controversial Disgusting Food Museum in Malmo, Sweden. The museum "collects" foods from around the world that its founders deem disgusting, with much controversy. Although the museum includes European foods like stinky fermented fish and salty licorice, it also includes many foods from non-Western societies. Many argue it reinforces cultural prejudices. Fan does not make specific value judgements about the museum itself, but does share her personal experiences as a Chinese person in the United States. I found the following passage in particular to be illuminating for Western audiences. Even so, disgust did not leave a lasting mark on my psyche until 1992, when, at the age of eight, on a flight to America with my mother, I was served the first non-Chinese meal of my life. In a tinfoil-covered tray was what looked like a pile of dumplings, except that they were square. I picked one up and took a bite, expecting it to be filled with meat, and discovered a gooey, creamy substance inside. Surely this was a dessert. Why else would the squares be swimming in a thick white sauce? I was grossed out, but ate the whole meal, because I had never been permitted to do otherwise. For weeks afterward, the taste festered in my thoughts, goading my gag reflex. Years later, I learned that those curious squares were called cheese ravioli. Asian foodways, especially Chinese foods, are often at the top of the "disgusting" lists - a combination of racism and deliberate misunderstanding of ancient foodways. For instance, lots of ancient Roman foods were also "gross," but are rarely consumed today, so modern Italians don't get the same level of derision. Many people like to argue that foods they find disgusting are "objectively" bad - but these same folks probably don't bat an eye at moldy congealed milk (blue cheese), partially rotten cucumbers (fermented dill pickles), or 30 day-old meat (dry aged steak). It's all about upbringing and perspective - something that folks who fail to recognize their own personal bias don't seem to get. And certainly, everyone is entitled to their own personal feelings on particular foods. For instance, despite several attempts, I can't stand the flavor of beets. But I know that, because I've tried them. "Disgusting" foods are often vilified by people who have never actually tried them. While immigrant foodways have often been the target of othering through disgust in the United States (see: Progressive Era Americanization efforts), for some reason the Whitest, most capitalistic of the historic American foodways - the 1950s - is the target of the same treatment today. Perhaps it is that in our modern era we have vilified processed corporate foods. And while I'm the first person to advocate for scratch cooking and home gardens and farmer's markets and all that jazz, there's much more seething under the surface of this than just a general dislike of gelatin. When processed foods first began to emerge in the late 19th century with the popularization of canned goods, they democratized foods like gelatin, beef consommé, pureed cream soups, and out-of-season fruits and vegetables that had previously been accessible only to the wealthy. Suddenly, ordinary people could afford to have salmon and English peas and Queen Anne cherries year-round - not just the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts of the world. After the austerity of the Great Depression and the Second World, the world seemed poised to combine those lingering ideas of what the wealthy ate with all the convenience modern technology could offer. Certainly, as some have argued, corporate marketing and test kitchens played a major role in shaping what Americans ate. But just because it was invented for an advertisement doesn't mean Americans didn't eat it on a regular basis. By the 1970s, many of those miracle technologies such as canning, freezing, dehydrating, reconstituting, etc. had become hallmarks of affordable - and therefore poor - foodways. "Government cheese," canned tuna, white bread, canned vegetables, mayonnaise, boxed cake and biscuit mixes, and yes, gelatin and Cool Whip were what poor people ate. Wealthier people ate "real" food - a trend that continues today. Disdain for poor people and their food seems universal, but even today, certain poor people have their foodways elevated over others (namely, pre-Second World War European peasants and select "foreign" street food purveyors). People living predominantly subsistence agricultural lives are seen as "authentic," while their urban counterparts, who consume processed foods by choice or by circumstance, are "selling out." But even "authenticity" only goes so far with some people. And even when foodies pride themselves on "bravely" eating chicken feet and fermented fish and other foods many would deem "disgusting," there's still an element of othering and disdain at play, a loud proclamation of worldliness and coolness at eating what their peers might avoid, that has little to do with actually understanding the culture behind the food. The food of the 1950s, once the clean, efficient, technologically advanced wave of the future quickly became the purview of the poor and working class. And while mid-century foodies like MFK Fisher and James Beard and (to a lesser extent) Julia Child descried processed foods and hailed European cuisines, peasant and "haute" alike, the vast majority of ordinary people ate ordinary, processed foods, and tried recipes dreamed up by home economists in corporate test kitchens. And within two decades, once the futurism wore off and the affordability factor set in, it became perfectly acceptable, cool even, to deride and mock those foodways. Which brings me back to the tuna on waffles. Canned tuna in cream of mushroom soup on top of hot, crisp waffles (probably NOT frozen, as frozen waffles weren't invented until 1953) is not something most of us are likely to eat on a regular basis today. However, it is hearkening back to a much older recipe: creamed chicken on waffles, which dates back to the Colonial period in America. Although the history of creamed chicken on waffles isn't crystal clear, this dish is clearly what Campbell's was emulating with their recipe. But what's the disgust factor? How is creamed tuna on waffles different from a tuna melt? Creamed chicken and biscuits? Fried chicken and waffles? Perhaps it is because today we associate waffles exclusively with sweet breakfast foods, so the idea of savory waffles is baffling. But they've only been used that way for a fraction of their history, for most of which they were used much more like biscuits or bread than a dessert. Or perhaps it's the tuna? Despite being hugely popular in the 1950s, tuna has fallen out of favor nationwide. Concerns about mercury, dolphins, and its association with poverty have helped dethrone tuna. But in the 1950s, it was a relatively new, and popular food. Today, it's a "smelly" fish associated with cafeterias and diners and cheap meals like tuna noodle casserole. Maybe it's the canned cream of mushroom soup? Cream of whatever soups remain a popular casserole (hotdish, for my fellow Midwesterners) ingredient even today, and the ability to replace the more labor-intensive white sauce with a canned good has helped many a housewife. Today, canned soups are vilified as laden with sodium and, for the creamy ones, fat. But canned goods have also been scorned as poverty food, with modern foodies touting scratch made sauces and fresh vegetables as healthier and better tasting. In the context of the 1950s, fresh vegetables were not always widely available as they are today, so canned and frozen vegetables took the drudgery out of canning your own or going without. In fact, our modern food system of fresh fruits and vegetables is propped up by agricultural chemicals, cheap oil, watering desert areas, and outsourcing agricultural labor to migrant workers or farms in the global south. Something many foodies like to conveniently overlook. My ultimate point isn't that people shouldn't reject processed foods in favor of scratch cooking. Indeed, I think that anyone who can afford to cook from scratch, should. But there's the rub, isn't it? Afford to. Because as much as homesteaders and bloggers and foodies like to proclaim that cooking from scratch is cheaper and healthier, it requires several ingredients they take for granted that aren't always available to everyone - a kitchen with working appliances, adequate cooking utensils, access to a grocery store and the means to transport fresh foods (fresh fruits and vegetables are HEAVY), the skills to know how to cook from scratch effectively and efficiently, and most importantly, TIME. As the old adage goes, you can have good, fast, and cheap, but never all three at once. Good and fast is expensive, good and cheap takes time, and fast and cheap is usually not very good. And when you're working multiple jobs to make ends meet, getting decent-tasting food on the table in a timely manner is more important than worrying about cooking from scratch. Those were the same concerns many working class people in the 1950s had, too. Even though the stereotypical White 1950s housewife had plenty of time to cook from scratch, plenty of women, especially women of color, worked outside the home in the 1950s. And mid-century Americans spent a far higher percentage of their income on food than they do today. And while fast food was around in the 1950s, it wasn't particularly cheap. For most Americans, it was an occasional treat, and restaurant eating in general was reserved for special occasions. Casual family dining as we know it today didn't exist. So that meant the typical housewife, wage working or not, had to cook 2-3 meals a day, nearly 365 days a year. Is it any wonder they turned to processed foods where most of the work was done for them? Maybe I've got a little personal bias of my own - after all I was raised in the land of tater tot hotdish and salads made with Cool Whip (That Midwestern Mom gets me). Foods that are often vilified by (frankly snobbish) coastal foodies, but that are "objectively" quite delicious. I like melty American cheese on my burger and grilled cheese as much as I enjoy making a scratch gorgonzola cream sauce. Fruit salad made with Cool Whip is a fun holiday treat. And while I prefer to make my own macaroni and cheese from scratch, I'd never mock or turn up my nose if someone offered me Kraft dinner. I think the driving force behind this pet peeve of mine is the idea that anyone can be the arbiter of taste (or disgust) when it comes to someone else's foodways. As my mom always used to say, "How do you know you don't like it if you don't try it?" Everyone's food history deserves respect and understanding. So let's give up the mean girl attitudes about foods we're not familiar with and let go of the guilt about liking the foods we like, be they 1950s processed foods or 500 year old family recipes. And the next time someone talks about how "gross" or "disgusting" a food is, or goes "Ewwww!" when presented with something new, give them a gimlet eye, ask them if they've ever had the dish, and then ask, "Who are you to judge?" The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed