|

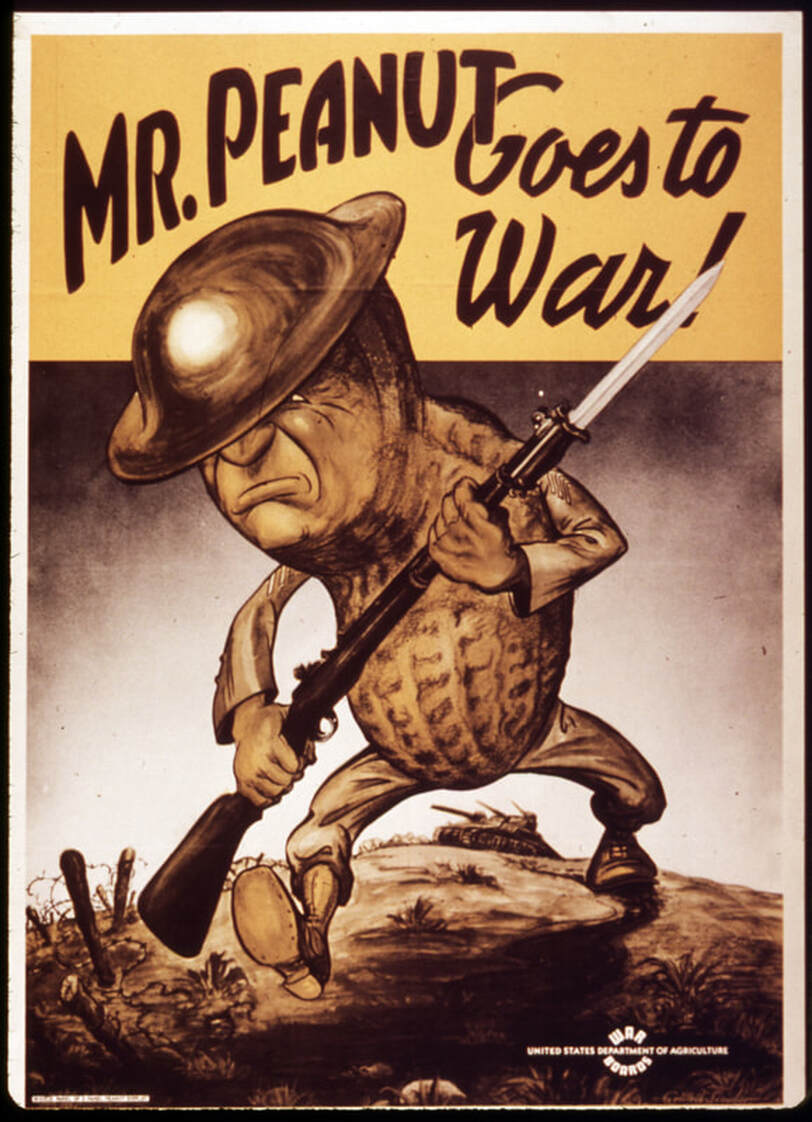

When you think of rationing in World War II, you may not think of peanuts, but they played an outsized role in acting as a substitute for a lot of otherwise tough-to-find foodstuffs, mainly other vegetable fats. When the United States entered the war in December, 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the dynamic of trade in the Pacific changed dramatically. The United States had come to rely on cocoanut oil from the then-American colonial territory of the Philippines and palm oil from Southeast Asia for everything from cooking and the production of foods like margarine to the manufacture of nitroglycerine and soap. Vegetable oils like coconut, palm, and cottonseed were considered cleaner and more sanitary than animal fats, which had previously been the primary ingredient in soap, shortening, and margarine. But when the Pacific Ocean became a theater of war, all but domestic vegetable oils were cut off. Cottonseed was still viable, but it was considered a byproduct of the cotton industry, not an product in and of itself, and therefore difficult to expand production. Soy was growing in importance, but in 1941 production was low. That left a distinctly American legume - the peanut. Peanuts are neither a pea nor a nut, although like peas they are a legume. Unlike peas, the seed pods grow underground, in tough papery shells. Native to the eastern Andes Mountains of South America, they were likely introduced to Europe by the Spanish. European colonizers then also introduced them to Africa and Southeast Asia. In West Africa, peanuts largely replaced a native groundnut in local diets. They were likely imported to North America by enslaved people from West Africa (where peanut production may have prolonged the slave trade). Peanuts became a staple crop in the American South largely as a foodstuff for enslaved people and livestock, but the privations of White middle and upper classes during the American Civil War expanded the consumption of peanuts to all levels of society. Union soldiers encountered peanuts during the war and liked the taste. The association of hot roasted peanuts with traveling circuses in the latter half of the 19th century and their use in candies like peanut brittle also helped improve their reputation. Peanuts are high in protein and fats, and were often used as a meat substitute by vegetarians in the late 19th century. Peanut loaf, peanut soup, and peanut breads were common suggestions, although grains and other legumes still held ultimate sway. George Washington Carver helped popularize peanuts as a crop in the early 20th century. Peanuts are legumes and thus fix nitrogen to the soil. With the cultivation of sweet potatoes, Carver saw peanuts as a way to restore soil depleted by decades of cotton farming, giving Black farmers a way to restore the health of their land while also providing nutritious food for their families and a viable cash crop. During the First World War, peanut production expanded as peanut oil was used to make munitions and peanuts were a recommended ration-friendly food. But it was consumer's love of the flavor and crunch of roasted peanuts that really drove post-war production. By the 1930s, the sale of peanuts had skyrocketed. No longer the niche boiled snack food of Southerners or ground into meal for livestock, peanuts were everywhere. Peanut butter and jelly (and peanut butter and mayonnaise) became popular sandwich fillings during the Great Depression. Roasted peanuts gave popcorn a run for its money at baseball games and other sporting events. Peanut-based candy bars like Baby Ruth and Snickers were skyrocketing in sales. And roasted, salted, shelled peanuts were replacing the more expensive salted almonds at dinner parties and weddings. Peanuts were even included as a "basic crop" in attempts by the federal government to address agricultural price control. They were included in the 1929 Agricultural Marketing Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, and an April, 1941 amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. Peanuts were included in farm loan support and programs to ensure farmers got a share of defense contracts. By the U.S. entry into World War II, most peanuts were being used in the production of peanut butter. And while Americans enjoyed them as a treat, their savory applications were ultimately less popular as an everyday food. But their use as source of high-quality oil was their main selling point during the Second World War. Peanut oil was the primary fuel in Rudolf Diesel's first engine, which debuted in 1900 at the Paris World's Fair. Its very high smoke point has made it a favorite of cooks around the world. During the Second World War peanut oil was used to produce margarine, used in salad dressings and as a butter and lard substitute in cooking and frying. But like other fats, its most important role was in the production of glycerin and nitroglycerine - a primary component in explosives. Which brings us to our imagery in the above propaganda poster. "Mr. Peanut Goes to War!" the poster cries. Produced by the United States Department of Agriculture, it features an anthropomorphized peanut in helmet and fatigues, carrying a rifle, bayonet fixed, marching determinedly across a battlefield, with a tank in the background. Likely aimed at farmers instead of ordinary households, Mr. Peanut of the USDA was nothing like the monocled, top-hatted suave character Planter's introduced in 1916. This Mr. Peanut was tough, determined to do his part, and aid in the war effort. The USDA expected farmers (including African American farmers) to do the same. Further Reading: Note: Amazon purchases from these links help support The Food Historian.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

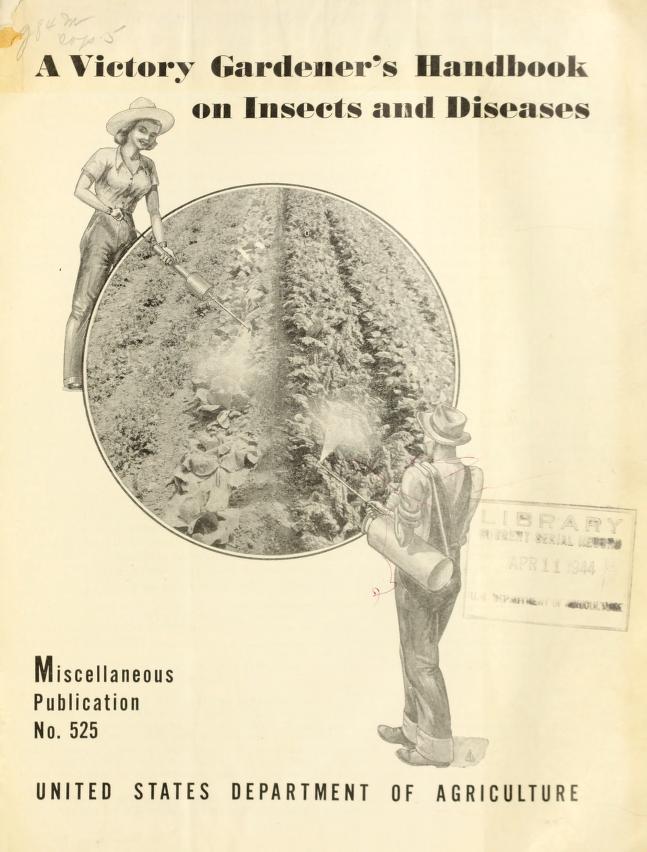

When it comes to modern ideas about Victory Gardens, there's a lot of romanticism and rose-colored glasses. Hearkening back to a kinder, gentler time when everyone pulled together toward a common goal and had delicious, organic vegetables in their backyards while they did it. But the reality was often much different from our modern perceptions. This propaganda poster is a good example of that. "Shoot to kill!" it says - "Protect Your Victory Garden!" In it, a woman wearing blue coveralls and a wide-brimmed hat, a trowel in her back pocket, sprays pesticide on a large, green insect (a grasshopper?) taking a bite out of an enormous and perfectly red tomato. She is protecting her victory garden from the "fifth column" of insect predation. "The Fifth Column" was a term used in the United States to describe sabotage and rumor-mongering by foreign spies. In this instance, insects become the "fifth column" because the act of eating crops threatens wartime food supplies, and is therefore sabotage by a foreign enemy. The food supply had to be protected and maximized at all costs. Anxieties around food supplies, especially in the winter when commercially produced foods might be scarce, meant that victory gardens took on special urgency. For the first time in at least a generation, Americans were having to put up their own food to help them get through the winter. And making every quart count was only possible if the garden did well. Lots of militarized language was used in propaganda concerning food, but none as war-like as the battle against pests in the victory garden. The idea that gardening before the 1950s was all organic is a common misconception. Even prior to the First World War, farmers and even some gardeners were dusting their crops with Paris Green and London Purple. Paris Green was a bright green toxic crystalline salt made of copper and arsenic. London Purple was calcium arsenate - normally white, but also a byproduct of the aniline dye industry, and was therefore sometimes tinged purple. Along with arsenate of lead, another salt, these three were termed arsenical pesticides and were used often in agriculture. The arsenic in rice scare from a few years ago was likely due to elevated levels of arsenical pesticide residue in the soil. Especially since rice from California, which first began to be commercial produced in 1912, but was not widely available across the country until the 1960s. That late adoption of rice agriculture meant that production was not as exposed to arsenical pesticides as elsewhere in the U.S. In 1944, the USDA published "A Victory Gardener's Handbook of Insects and Diseases" that identified common pests and suggested remedies. Calcium arsenate and Paris green were recommended (albeit with warnings about arsenic residue), along with:

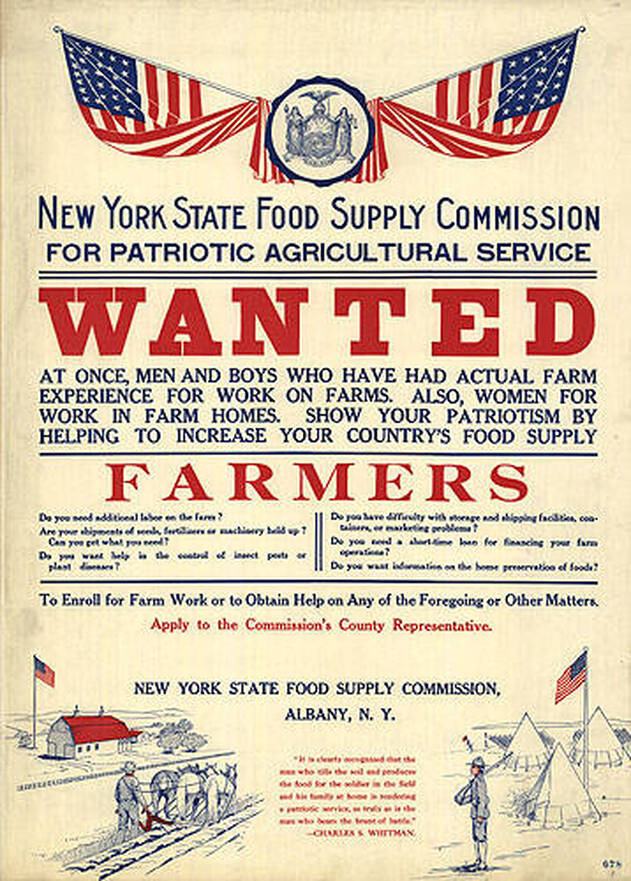

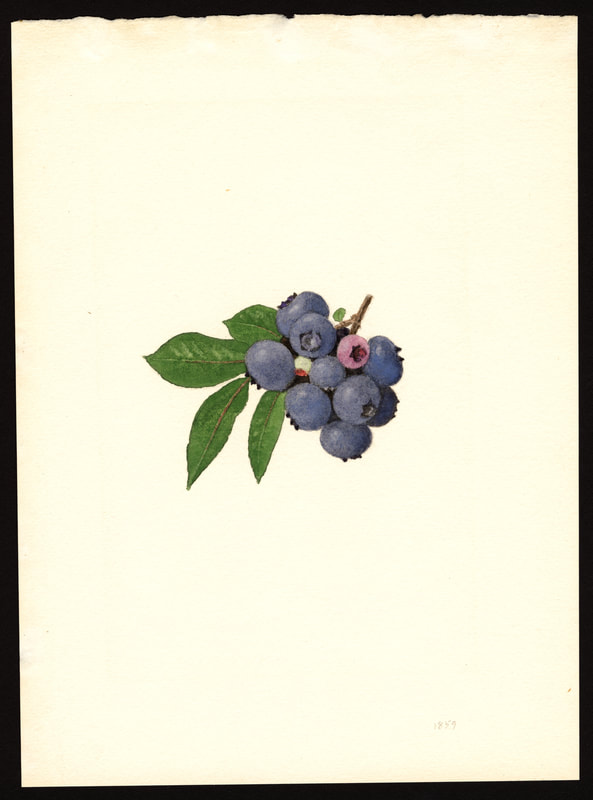

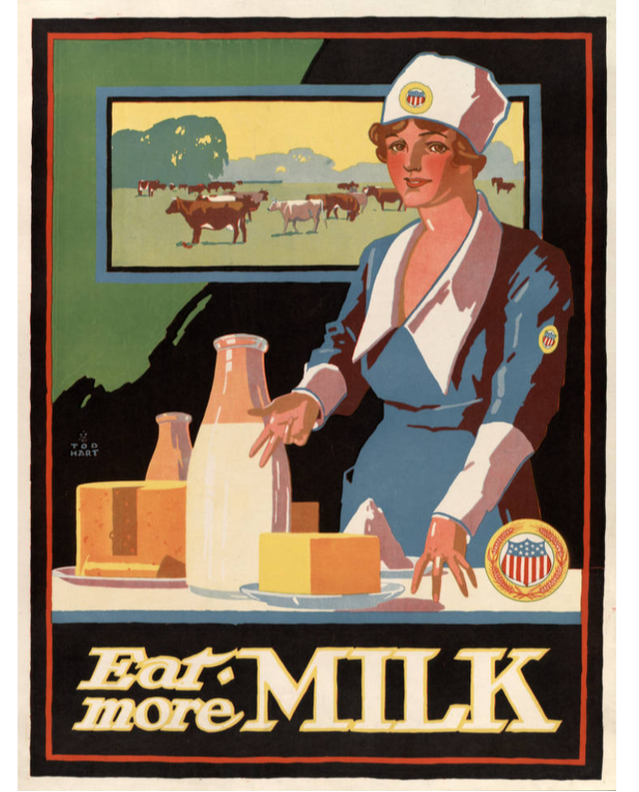

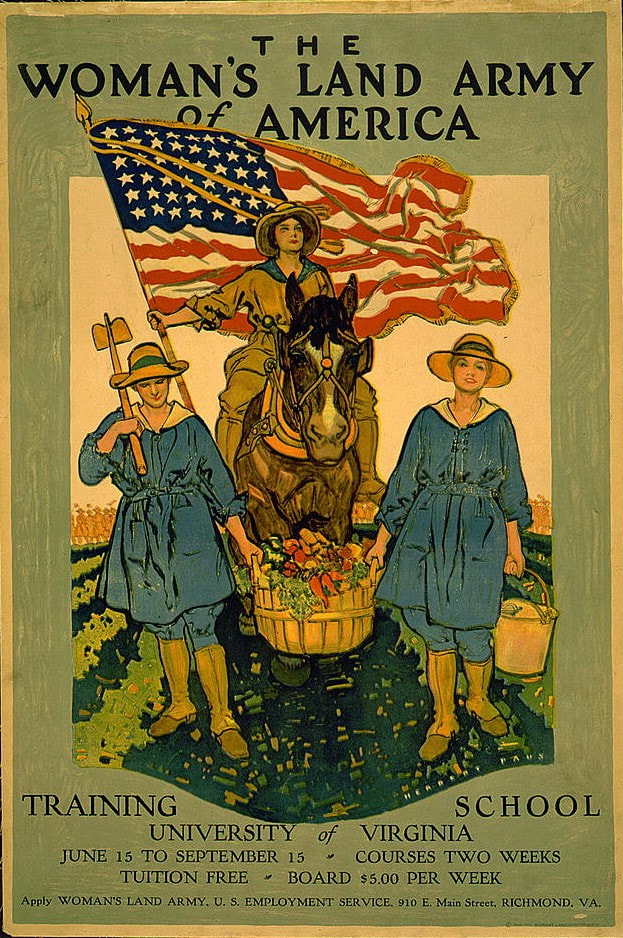

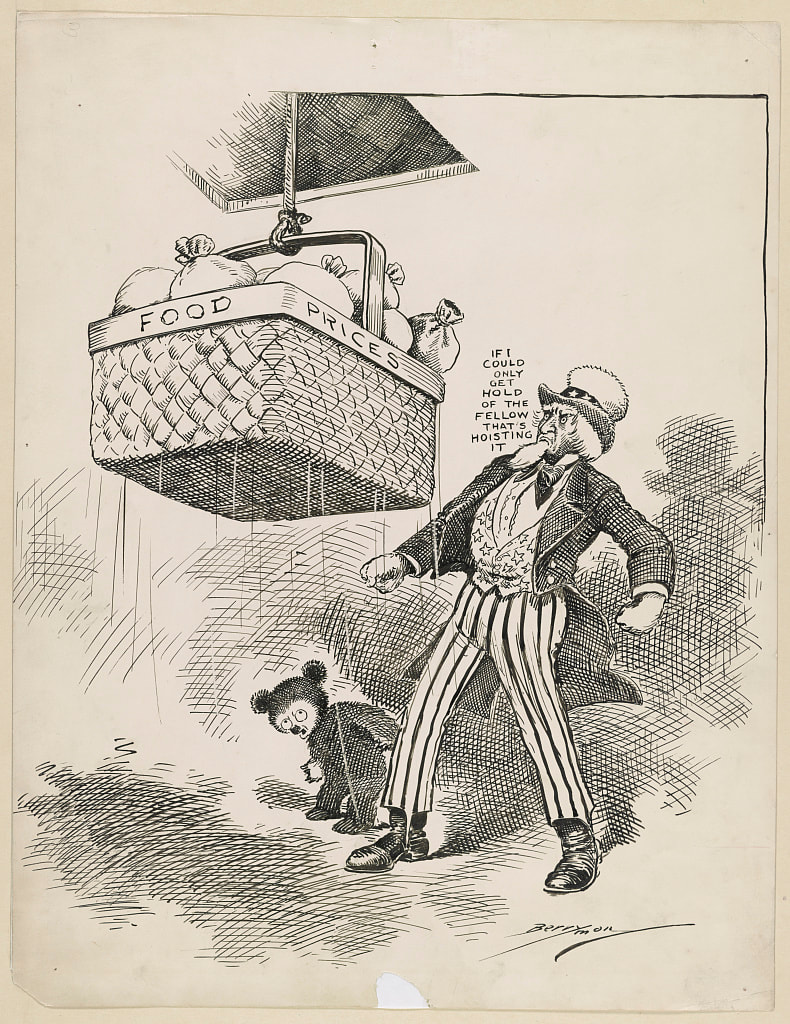

Although some people may have chosen not to purchase pesticides, likely due to expense more than concerns about poisoning, the emphasis on the danger pests posed to the general food supply continued. Hand atomizers, which is what the hand sprayer in the propaganda poster is called, were frequently depicted in print and even on film. Despite USDA warnings about application safety, no one is ever seen applying the highly toxic, aerosolized liquid pesticides with protective equipment. However, the science of the effects of exposure to toxic chemicals was not yet well-studied. DDT, invented in 1939, was deemed a miracle chemical and helped dramatically reduce diseases like malaria and water-borne bacteria that in previous wars had sometimes killed more soldiers than the conflict itself. Because soldiers faced no immediate effects, the chemical was deemed safe, and used everywhere from farms to a treatment for lice in children. But like the arsenical pesticides, the effect was cumulative, and it wasn't until Rachel Carson's 1962 Silent Spring that Americans began to wake up to the dangers of pesticides. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! This beautiful propaganda poster from the First World War is the result of a controversy. The fresh-faced young white woman in her United States Food Administration-approved food conservation uniform and cap, gestures to a table with an enormous glass bottle of milk, a huge block of butter, a wheel of cheese, and what is either a mound of cottage cheese or some sort of milk pudding. A framed view of dairy cows in a green field floats behind her. It exhorts the reader to "Eat more MILK." But why? Throughout World War I in the United States, dairy farmers struggled. Feed prices went up, and retail prices of milk went up, but the wholesale prices that farmers got from milk dealers and dairies remained static. Despite dozens of local and state and federal inquiries, no single culprit for high milk prices was ever discovered. The result of high prices combined with government advocating for increased production and Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet, particularly for children, meant that by the spring of 1918 there was a serious milk surplus. For several years, the butter, cheese, and condensed milk industries had absorbed the milk surplus, but by the spring of 1918 they were also over capacity. The United States Food Administration, in conjunction with state governments, embarked on a campaign to try to get Americans to consume more milk, with limited success. In May of 1918, New York City hosted the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition at the Grand Central Palace. New York State Governor Charles Whitman opened the exposition, and United States Food Administrator Herbert Hoover also attended. Home economists praised milk-based dishes such as puddings, custards, and the use of cottage cheese and brick cheeses - hence the phrase "Eat more milk," rather than "drink," as drinking cows milk was not common among adults. Cottage cheese and brick cheese were touted as affordable meat alternatives. Despite the classic Progressive Era boosterism, including the attendance of "famous" cows at the exposition, retail milk prices remained relatively high, with seasonal dips in the spring and early summer. Federally fixed milk prices helped solve the problem short-term, but even after the war, dairy farmers were subject to a Congressional investigation to determine whether they price gouged consumers (they didn't), and the right of farmers to form co-ops was in danger of becoming illegal under anti-trust laws. Ultimately, it was falling grain prices and rising postwar demand that evened out prices, although to this day the dairy industry still struggles. Even after the war, Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet persisted, and were recycled during the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase something from a link, you'll be supporting The Food Historian! The Woman's Land Army of America came out of the women's suffrage movement as a way for young, largely college-educated women to prove their worth during wartime by providing agricultural labor to make up labor shortages thanks to the draft, better wages in industrial work, and the need to increase agricultural production. The movement started in New York State, and has been ably chronicled by Elaine Weiss' book The Fruits of Victory. This beautiful propaganda poster from the University of Virginia Training School for the Woman's Land Army of America is just delightful. The imagery is evocative. A young woman holding an American flag, which billows out behind her, is dressed in a khaki uniform and riding a plow horse through a green agricultural field, simultaneously calling to mind a mounted standard bearer, Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders, and Army cavalry. In the foreground, two young women in matching blue uniforms share the load of a bushel basket laden with vegetables. The woman at left has a hoe over her shoulder, reminiscent of how a soldier might carry a rifle. The woman at right carries what appears to be a milk pail. Far in the background, what appears at first glance to be a field of ripe wheat is in fact a golden line of uniformed women with agricultural implements on their shoulders, marching behind the leading three. The costumes were among the official Woman's Land Army costume - in khaki and blue chambray. A loose tunic with full sleeves (rolled up) and a cinched waist falls to the knee, covering military-style jodhpurs and puttees over sensible shoes. A broad-brimmed hat and a kerchief around the neck complete the sensible outfit, which somehow still scandalized some members of the public at a time when women's skirts rarely rose above the ankle. The poster is advertising the Woman's Land Army's Training School at the University of Virginia. Designed to give young women basic agricultural skills, and sometimes specialized skills like the use of tractors, the schools were generally free, but required payment for room and board, as this one does at $5.00 per week for a two week course. Sometimes called "farmerettes," likely a combination of the terms "farmer" and "suffragette," and one which not every member of the Woman's Land Army enjoyed. But then, not every farmerette was a member of the Woman's Land Army, and the term actually predated the U.S. entrance into the war. The women saw some success in the adoption of their labor in agriculture, but it created no sea change of labor distribution post-war. Most farmers outside orchards and truck farmers mechanized in the face of labor shortages, rather than using farmerettes or farm cadets (teenaged boys released from school to work on farms). And increasing specialization of crops and livestock meant that mechanization was easier and more profitable than hiring young women at good wages for just 8 hour days (pre-war farm laborers had no such protections). The Land Army would be revived during World War II, this time divorced from its suffragist origins and encouraging young people of both sexes to assist with farm labor. But that's a post for another day. Woman's Land Army Books Fruits of Victory: The Woman's Land Army of America in the Great War by Elaine F. Weiss Weiss tracks the evolution of the Woman's Land Army in America, focused primarily on New York State, which was where the WLA officially began in the U.S. In intimate detail, she introduces us to a whole host of historic characters, including leading lights of the women's suffrage movement, and how they tried to prove women's agricultural labor was the future.  Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement by Cecilia Gowdy-Wygant Cultivating Victory examines the interrelationships between the British and American Woman's Land Armies, as well as their connections to the war garden and victory garden movements. Covering both the First and Second World Wars, Gowdy-Wygant compares and contrasts the efforts in both nations and the differences and similarities between both wars. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!  "New York State Food Supply Commission for Patriotic Agricultural Service. Wanted at once, men and boys who have had actual farm experience for work on farms. Also, women for work in farm homes. Show your patriotism by helping increase your country's food supply. Farmers - Do you need additional labor on the farm? Are your shipments of seeds, fertilizers or machinery held up? Can you get what you need? Do you want help in the control of insect pests or plant diseases? Do you have difficulty with storage and shipping facilities, containers, or marketing problems? Do you need a short-term loan for financing your farm operations? Do you want information on the home preservation of foods? To Enroll for Farm Work or to Obtain Help on Any of the Foregoing or Other Matters. Apply to the Commission's County Representative. New York State Food Supply Commission, Albany, N.Y." 1917, Temple University. The United States entered the First World War on April 6, 1917. On April 13, New York State Governor Charles S. Whitman appointed a Patriotic Agricultural Service Committee. On April 17, an Act of the New York State legislature created the New York State Food Supply Commission. This propaganda poster is likely from the spring of 1917 for several reasons. First, by the fall of 1917, the commission had changed its name to the New York State Food Commission, Second, the emphasis on laborers with farming experience, rather than the inexperienced, was a hallmark of early efforts to increase agricultural production. The poster reads: "New York State Food Supply Commission for Patriotic Agricultural Service. Wanted at once, men and boys who have had actual farm experience for work on farms. Also, women for work in farm homes. Show your patriotism by helping increase your country's food supply. Farmers - Do you need additional labor on the farm? Are your shipments of seeds, fertilizers or machinery held up? Can you get what you need? Do you want help in the control of insect pests or plant diseases? Do you have difficulty with storage and shipping facilities, containers, or marketing problems? Do you need a short-term loan for financing your farm operations? Do you want information on the home preservation of foods? To Enroll for Farm Work or to Obtain Help on Any of the Foregoing or Other Matters. Apply to the Commission's County Representative. New York State Food Supply Commission, Albany, N.Y." Interestingly, this poster not only focuses on farm labor, seed acquisition, farm loans, etc., but also on securing women's labor "for work in farm homes." The general idea was that women could help relieve some of the household burden on farm wives, and assist with food preservation, so that farm wives, who were often more experienced in farm management than most farm laborers, could assist their husbands. Neither plan really worked out well. The few women who were interested in farm labor wanted to do the agricultural work - not housework. And while experienced farm hands were in high demand, that drove wages up considerably - not every farmer was able to afford them. The Food Supply Commission coped by helping some farms modernize. They purchased a series of tractors - then still a rarity in the Northeast - and helped farmers acquire seed potatoes, beans, and more. But it took until the end of 1917 for the Commission to find its footing. By then, it became a partner of the United States Food Administration, working hand-in-hand with Hoover. You can read more about the New York State Food Supply Commission and its early work in its annual report for 1917, published in 1918. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Even though the United States didn't officially join the war until April 7, 1917, the U.S. had long supported the Allies and neutral nations through the sale of agricultural products. But the 1910s was a time of little government regulation and increasingly global commerce. The Allied European nations all leaned heavily on their colonial holdings to produce food and war materiel, what goods they could get through German U-boat blockades. Part of the reason for German expansionism in Europe was a lack of colonial holdings (also the reason for the Second World War, as ably argued by Lizzie Collingham in The Taste of War), and therefore a lack of agricultural capacity. As an independent nation rich in natural resources (through their own brutal colonization of the continent), the United States was able to meet the increasing European demand. Midwestern wheat farmers in particular were very happy, as the increased demand increased prices. But while farmers were happy to have good return on their crops, the increased demand from abroad was increasing food prices at home. The High Cost of Living or "H.C.L." as it was often referred to in the press, was the topic of much discussion throughout the Progressive Era. Kosher meat riots in 1902 and again in 1910 in New York City were only the beginning. Exacerbated by the war, by 1917 rising food prices led women around the world to riot against food prices that increased sometimes 200% in a matter of weeks. You can read more about the food riots of New York City in a previous blog post. In this image (hard to tell if it was used as a political cartoon or a poster), Uncle Sam looks at a picnic basket labeled "Food Prices" being hauled up through the ceiling. He mutters to himself, "If only I could get hold of the fellow that's hoisting it." His fists are at his side, impotently, while a small teddy bear (whose significance is unclear, but may have been a reference to Teddy Roosevelt --- see the update below!) looks on in dismay. The image reinforced the idea that the federal government had little or no control over food prices. Ultimately, the food price question was never really settled. Boycotts temporarily created surpluses, which lowered prices. But only the increased wartime production when the U.S. entered the war in 1917 seemed to raise wages and increase agricultural supply enough to address rising food prices. And when the war ended in late 1918, food prices increased again as regulating government agencies like the United States Food Administration were dismantled, but relief efforts abroad continued, along with the supply of the American Expeditionary Forces, many of whom did not return until the end of 1919 or even later. Increased production encouraged during the war years resulted in an agricultural depression in the 1920s, as European nations recovered their own agricultural production and demand for American exports fell. The agricultural depression was an early harbinger of the Great Depression. Stay tuned next week for propaganda about the High Cost of Living during the Second World War. UPDATE: Many thanks to Food Historian reader Peter K. for giving us some more context about the teddy bear! Apparently artist Clifford Berryman was the originator of the Teddy Bear, which was indeed inspired by Theodore Roosevelt. Adding the teddy bear to various political cartoons was one of Berryman's signatures, although the bear was often the star of the show. Once Teddy Roosevelt left office, Berryman also used the bear to represent his own opinions in political cartoons. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!  “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf, not the farmer of the United States who works and sacrifices to fill the holds of victory ships…,” says the narrator as an oversized silhouetted farmer pours grain into the hold of a ship. Still from the film "Food Will Win the War" (1942). Courtesy Cartoonresearch.com Previously, we met Jack Sprat and his wife in a fairytale cartoon propaganda poster. This week, we go all out total war with Walt Disney. Produced by Disney in 1942, "Food Will Win the War" was a propaganda film of the Agricultural Marketing Administration, under the auspices of the United States Department of Agriculture. Narrated like a newsreel, the cartoon illustrates the might of American agriculture, in brilliant technicolor. The cartoon illustrations of the overwhelming productivity of American agriculture compare mind-boggling production numbers to well-known landmarks and other Very Large Things. Flour to blizzards, bread to the Egyptian pyramids, tomatoes to the Rock of Gibraltar, cheese to the moon, etc. When getting to meat production, we get to see the Disney's Three Little Pigs, leading a parade of hundreds of hogs, playing "Who's Afraid of the Big, Bad Wolf?" on fife and drum. Periodically, we are reminded that the size of several of these items could crush Berlin, including a very plump blonde representing American fat and oil production. One scene compares American agriculture to a giant bowling ball, which is depicted rolling through Nazi headquarters (tattering the Nazi flag in the process), and bowling over pins caricaturing Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Emperor Hirohito. The film closes with a grim montage of the challenges faced by shipping and a call to the Four Freedoms outlined by FDR - Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. Like many propaganda films and newsreels from World War II, this one has plenty of bombast, with good and evil portrayed in stark black and white terms (even though the animation is in color). Released to American audiences on July 21, 1942, it had several goals. One was to buoy American confidence in food supplies. There were concerns that the U.S. was shipping too much produce overseas and that there would be shortages at home. These concerns were not unfounded, but wartime production increased enough that even though rationing eventually grew tight, everyone had enough to eat. Another was to impress upon foreign audiences that American production capacity was overwhelming and would strengthen the Allies, who had been at war for over two years already. In 1941, Disney was suffering major financial losses from Fantasia - it was a box office flop and made just a fraction of what it cost to produce. You can see the economy of animation in many of the scenes of this film - where largely still images move across the frame or zoom in or out - achieved by layering cells. But the success of Disney's animated films for the war effort helped keep the studio afloat during the war. They became well-known in particular for training films, as Disney animators were able to illustrate in fine detail mechanical operations and theoretical scenarios that would be difficult or impossible to film in real life. Some speculate that without World War II, Disney Studios might have gone under after only a few films. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

George Washington Carver is a historical figure you may have heard of. Perhaps you grew up learning in elementary school that he invented peanut butter (he didn't), or perhaps you know his work in popularizing sweet potatoes. You might know he was born into slavery, and through his pioneering efforts at plant science, helped found the agricultural college at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

But the bulk of his accomplishments have been glossed over in popular culture, until now. Grist recently published an excellent overview of the real contributions Carver made, and why they have largely been ignored. George Washington Carver died on January 5, 1943. Just a few months before his death, he published Nature's Garden for Victory and Peace, his contribution to the victory garden conversation during the Second World War.

Many people wrongly attribute Carver's booklet as a guide to victory gardens. In fact, it is a guide to foraging, and in line with Carver's ideas about food sovereignty that were decades ahead of their time.

Carver knew that access to land meant access to food, and even if Black families were denied access to land to grow gardens, they could forage in the wild public spaces or unclaimed verges of roads, edges of fields, etc. Still coming out of the Great Depression in 1941, people were eager to supplement often meager food supplies however they could. Free food was worth the labor to collect and process it. Nature's Garden lays out not only the common and botanical names of many wild-growing and native greens and herbs, some with accompanying line drawings, but also advice for harvesting and processing, recipe suggestions, and advice on drying garden produce for long-term storage - cheaper and easier than canning, which required expensive equipment and jars. Carver also includes references to Indigenous food uses, such as the use of sumac in making "lemonade," and directions for how to make "Lye Hominy," using the nixtamalizing process invented by Indigenous peoples in Mexico to hull corn and make the naturally-occurring niacin in the corn absorbable by the human body. The booklet was given away free - one copy per person. Additional copies could be acquired at the cost of printing. A Simple, Plain, and Appetizing Salad

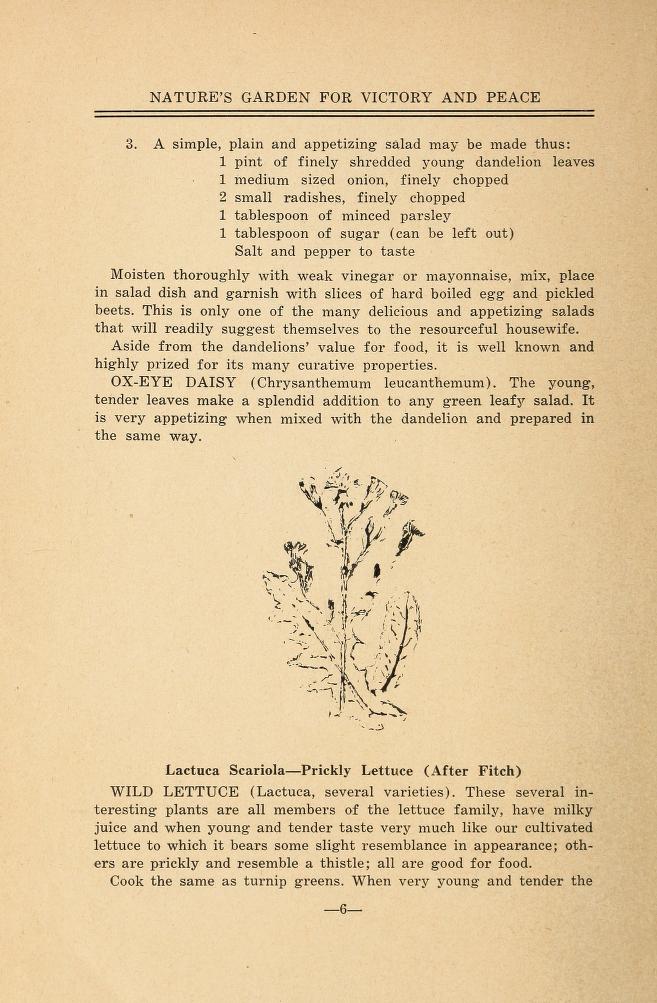

One of the few recipes Carver actually outlines in Nature's Garden is also one of the first - a recipe for dandelion salad.

It reads: "A simple, plain and appetizing salad made be made thus: 1 pint of finely shredded young dandelion leaves 1 medium sized onion, finely chopped 2 small radishes, finely chopped 1 tablespoon of minced parsley 1 tablespoon of sugar (can be left out) Salt and pepper to taste "Moisten thoroughly with weak vinegar or mayonnaise, mix, place in salad dish and garnish with slices of hard boiled egg and pickled beets. This is only one of the many delicious and appetizing salads that will readily suggest themselves to the resourceful housewife." A modern incarnation might be made with arugula, instead of dandelion leaves, if you are unable to forage your own safely.

Today, other foragers are trying to reclaim foraging for BIPOC communities. Alexis Nikole Nelson, also known as Black Forager, is one of those people. Like Carver, she reminds everyone that foraging has been the purview of BIPOC communities for as long or longer than the white male foragers who often get all the attention these days.

I love Alexis' near-daily posts and how she cooks the food she forages - the most important information and often left out of the foraging equation. She's been profiled by TheKitchn, and Civil Eats, but you can learn the most by just following her on Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, or Facebook. You can also support her work by becoming a patron on Patreon! Further Reading

To learn more about George Washington Carver, check out these excellent resources.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

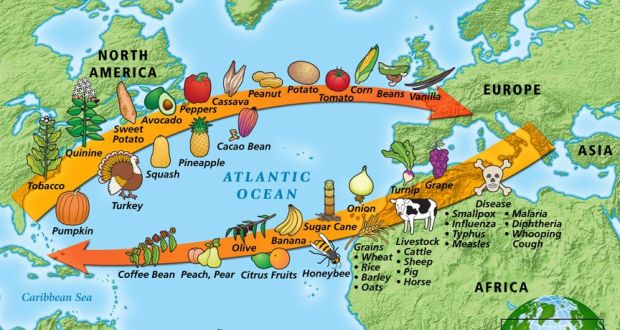

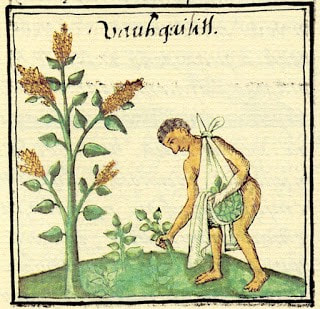

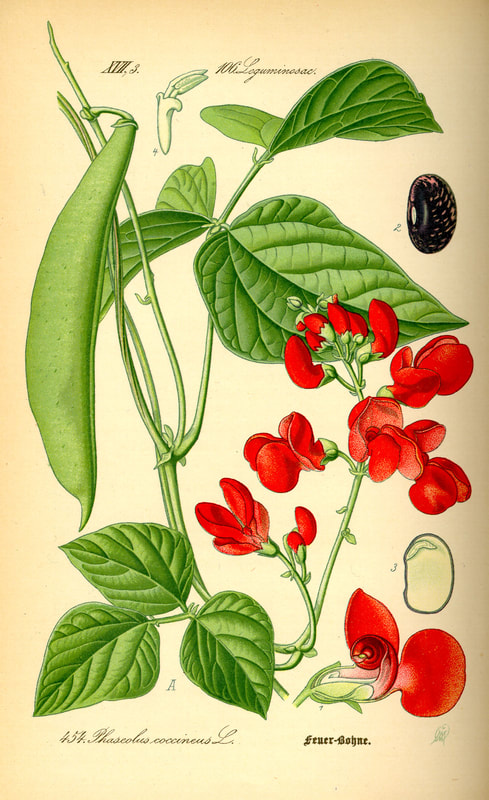

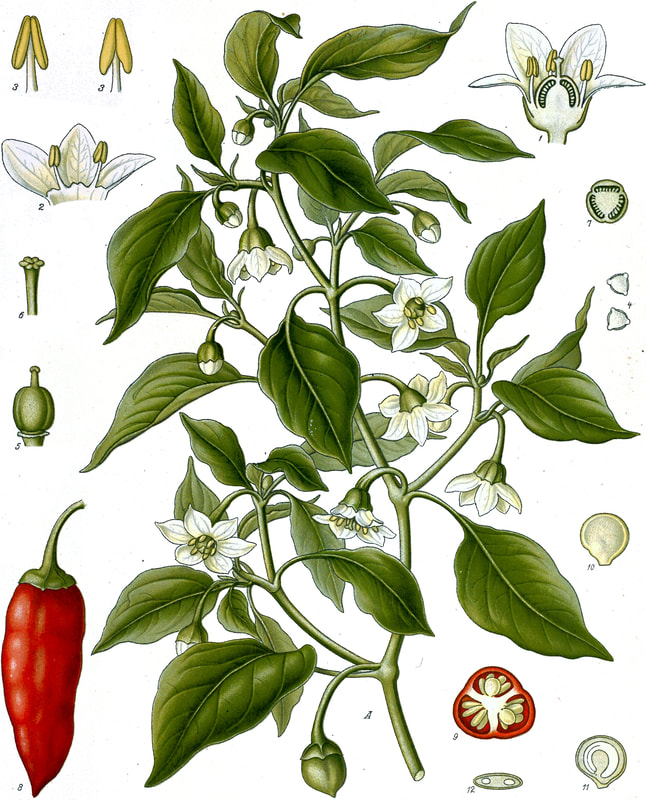

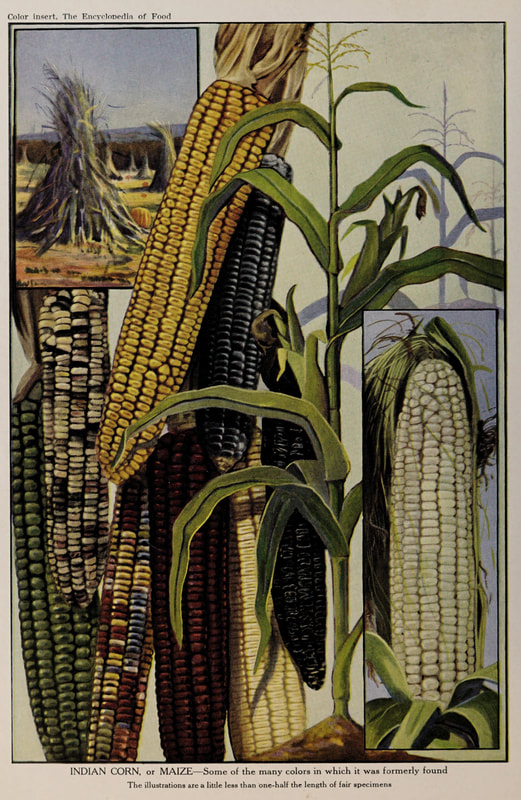

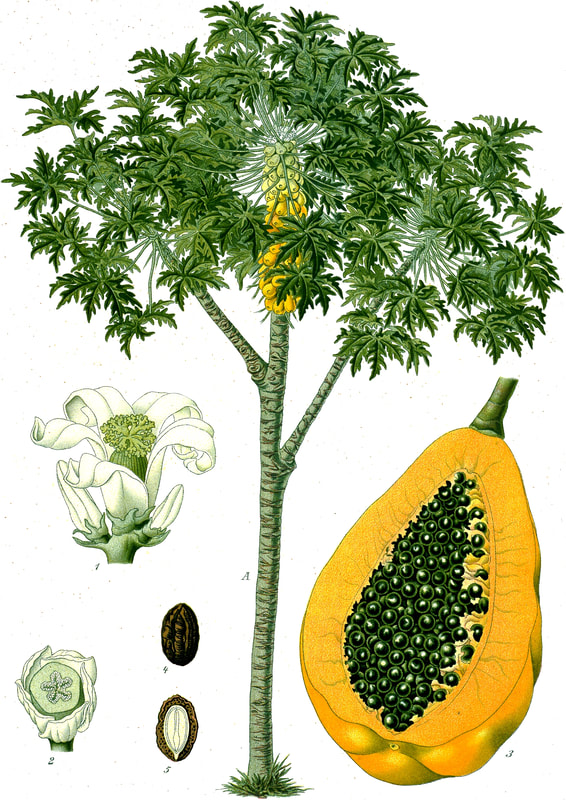

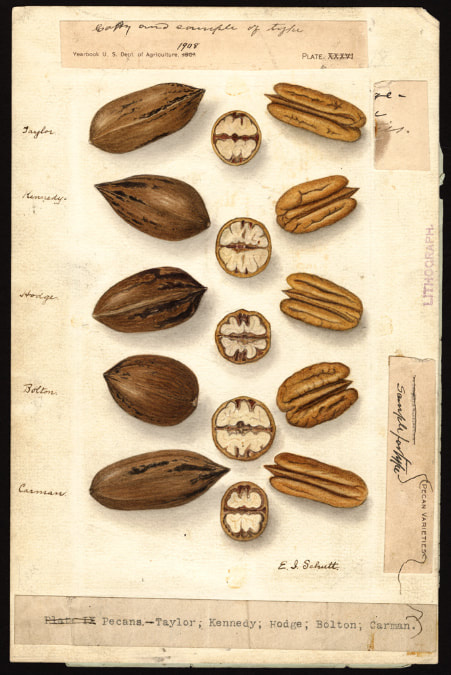

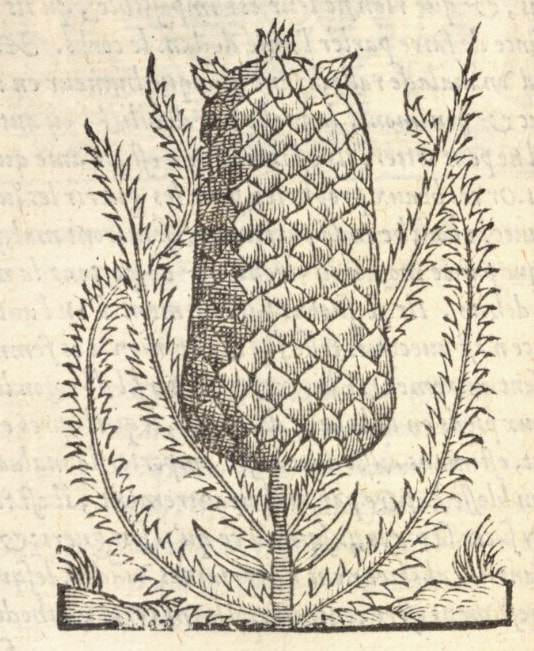

Today is Indigenous Peoples' Day. What, you thought it was Columbus Day? Well, for some people who don't know any better it still is, but Columbus was a pretty terrible person, driven by greed, and he didn't "discover" anything. Instead, he did things like sell 9 year old Taino girls into sex slavery, cut off children's hands if they didn't meet gold quotas, and generally committed genocide and slavery against every non-white person he met. He almost completely wiped out the Arawak-speaking peoples of the Caribbean, including the Lucayan people of the Bahamas and especially the Taino people of Hispaniola (present day Haiti and Dominican Republic). But as with most genocides, they're never 100% successful, and people throughout the Caribbean are descended from Taino people. One thing Columbus did lend his name to is a term called "The Columbian Exchange." The term was coined in the 1970s by historian Alfred W. Crosby, who studied the impacts of geography and biology on history, specifically the relationship between Europe and the rest of the world. Because Columbus was the first European to bring back many of the plants now used across the world, the exchange is named after him. Essentially, Irish potatoes, Italian tomato sauce, Swiss chocolate, Thai chilis, and a whole host of other important international foods are not actually from any of those places. They are ALL indigenous to North and South America and did not exist outside those continents prior to 1492. I'm going to catalog Indigenous American foodways in a minute, but first I want to emphasize how important it is to recognize that all of these foods are a result of Indigenous agricultural innovation. There is a tendency among many White folks to assume that these foods were just growing "wild" - and while that may be the case with some fruits, the vast majority were cultivated by Indigenous people, often in brilliant and surprising ways. And if you'd like to skip the list and go straight to figuring out where you can buy Indigenous foods and support Indigenous growers, harvesters, and producers, a good starting place is the list created by the Toasted Sister podcast. It's not comprehensive, but it's a great start. You can also check out this directory of certified American Indian Foods producers by the Intertribal Agricultural Council. You can even search by state! A small disclaimer - this is obviously not a complete list of Indigenous foods - I thought I would list the most influential foods globally and in the modern American diet. But I encourage you to use the magic of the internet to see what other foods you can find Indigenous to the area you live. And one final note - while it is important to preserve Indigenous foods and seeds, it's equally important to support the Indigenous people working to preserver them, like the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network. So while groups like Seed Savers Exchange are great, I encourage everyone to seek out Indigenous-owned and Indigenous-led companies and groups when choosing who to support. AmaranthWhere I grew up on the Northern Plains, in Lakota territory, one species amaranth is often known as "pigweed," and is considered a noxious weed by farmers. But Indigenous people know it as an important grain crop. Developed by the Aztec, amaranth was banned by the Spanish. The leaves of amaranth are also edible and some varieties are known as "callaloo," an important green vegetable for enslaved African peoples throughout the Caribbean and southern United States. If you're a gardener, "love-lies-bleeding" is a decorative variety of amaranth. There are dozens of varieties, but amaranth grains are often available for purchase from specialty stores and online. AvocadoAvocadoes, modern purview of hipsters, are actually an ancient fruit developed near Puebla, Mexico nearly 10,000 years ago (seriously, the world owes so much to Mexico in terms of agricultural innovation). The Indigenous residents of Puebla began cultivating the tree as much as 5,000 years ago. Modern-day avocadoes come in a whole host of varieties, but residents of the U.S. are most familiar with the Hass variety. Introduced to the American Southwest in the 1830s, avocado consumption in the United States didn't really take off nationally until the 1930s, influenced by California cuisine and used primarily in salads. Look in old cookbooks for references to "alligator pears," so named because of their bumpy green skin and pear shape. BeansBeans, especially climbing pole beans like the scarlet runner bean, are an important component of the Three Sisters style of agriculture, in which pumpkins or squash, corn, and beans are grown in concert with each other. The corn provides the stalk for beans to climb, the beans fix nitrogen in the soil for the corn and squash, and the broad leaves of the squash shade the ground, helping to prevent competing plants from growing and keeping the soil moist. Although some varieties of legumes did exist in Europe prior to the Columbian Exchange, notably chickpeas, peas, lentils, and broad beans, the introduction of the wide variety of cultivated Indigenous beans to Europe, especially kidney beans, including what would become the famous Italian cannelini. Black beans, pinto beans, and pink beans are other Indigenous varieties. Blueberries Image of the Weymouth variety of blueberries (scientific name: Vaccinium corymbosum), with this specimen originating in New Jersey, United States. Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705, 1940. Lowbush blueberries (often marketed in grocery stores as "wild" blueberries) are native to North America, as other other blueberry-like fruits including huckleberries and juneberries (also known as serviceberries). Although these plants grew wild, blueberry barrens and other stands were often maintained by Indigenous peoples. Dried blueberry and cracked corn mush may have been served at the First Thanksgiving. Early European observers misnamed them "bilberries," after a relative native to Britain. In the early 20th century, highbush blueberries were cultivated from Indigenous blueberries in New Jersey. Highbush blueberries are bigger and therefore easier to harvest and ship than lowbush blueberries and are most often what you'll find in grocery stores today. CashewMost people probably associate cashews with Southeast Asia and Indian cuisines. But cashews are actually native to Brazil. The word "cashew" is a corruption of the word "acaju," which is Tupi for "nut." The Tupi people (of which there are dozens of sub-tribes) were who the Portuguese encountered when they first arrived there in the early 1500s. It was the Portuguese who brought the cashew to Goa, India in the late 1500s, where it thrived. Today, most commercially produced cashews are grown in India. ChiaMaybe you've noticed the trend for chia puddings these days. Or perhaps you're old enough to remember the Chia Pet craze of the 1980s. But the origins of chia are much older than you might suppose. Native to Central America, chia is thought to have been cultivated by the Aztecs as much as 3,500 years ago. An important staple crop throughout Mesoamerica, it was likely also used for religious purposes and may have been banned by Spanish colonizers for that reason. Thankfully, it survived. Chilis & PeppersChili peppers - from which all modern capsicums are derived, including bell peppers - were cultivated in Mexico as early as 6,000 years ago. Self-pollinating, chilis quickly spread throughout Mexico and Central and South America. Known in many countries by their cultivar name - capsicum - in the United States we call them "peppers" because Columbus and other Europeans associated them with the heat they had previously only known from black pepper. Like cashews, chili peppers were brought to Southeast Asia by Portuguese traders, where they quickly took hold as an essential part of many Asian cuisines. In the United States, New Mexico is best known for its production of chili peppers and its chili-eating heritage. Chilis are an essential ingredient in salsa, and Indigenous Mexican peoples use all different varieties (not just jalapenos and habaneros) for different levels of heat and flavor. ChocolateToday, chocolate is most often associated with Switzerland, Germany, and France. But its origins are ancient and date to Mesoamerica. The oldest references are for the Olmec peoples of central Mexico, who used it in religious ceremonies. But it was also used by the Maya and Aztec peoples, who both used cocoa beans as currency and used chocolate beverages in daily life and religious ceremonies. Although the origin of cacao plants is contested, they appear to have been common in Central America and actively cultivated as early as 5,300 years ago. Chocolate's chemical signature is often tracked as part of archaeological digs, and recent finds have suggested that its use and cultivation are earlier and more widespread than previously known. When it was introduced to Europe, Europeans treated it much like they did another dark, bitter beverage - coffee - by adding cream and sugar to it and drinking it for breakfast. By the 18th century, mechanization and slavery had made chocolate affordable to the middle classes. But it wasn't until the 19th century that chocolate bars, mixed with vanilla, sugar, dairy solids, and cocoa butter, came into widespread use. Corn (Maize)For most Americans, corn is hybridized sweet corn, popcorn, and maybe yellow or white cornmeal (or grits). But corn comes in thousands of different varieties and can be processed in hundreds of different ways. Did you know, for instance, that different varieties of corn - popcorn, dent, flint, flour, etc. - were cultivated for different uses? And that most corn can be eaten at all stages of development? And that "sweet" corn was originally just eating immature "green" corn before the sugars had turned to starch? Indigenous cooks also developed nixtamalization - a process whereby corn is soaked in wood ashes and water (i.e. lye) to de-hull and soften the corn. Nixtamalization also has the important additional benefit of releasing the niacin (Vitamin B3) from the corn so that it can be processed by the body. Niacin deficiency, also known as pellagra, plagued 19th and early 20th century White Americans, who did not know how to process the corn properly. Corn was developed from a grass native to south central Mexico called teosinte - which is still used today in Mexico as a fodder for livestock. As cultivated varieties spread throughout North America, they took on different characteristics as they cross-pollinated with other varieties and native species of teosinte. Corn is wind pollinated, meaning that it cross-breeds easily. Today, corn's global dominance is almost entirely related to its role as livestock feed, especially with beef. Sadly, beef cattle are not well suited to being raised on corn, and "corn fed beef," which is designed to put on a lot of fat for your "well-marbled" steak, is actually extremely destructive to bovine digestive systems. Not to mention unhealthy for humans, too. American agricultural subsidies for corn, which allow food processors to purchase it for less than it costs farmers to produce, have also allowed the proliferation of its use as an industrial food, notably corn syrup, but corn is now in almost everything we eat. And not in a good way. If you want to help Indigenous producers, buy Indigenous-grown Indigenous corn products. Here in New York, you can buy Iroquois White Corn. Don't feel like eating corn but want to help? Support Indigenous seedkeeper groups. Can't find one in your area? Donate to the Indigenous Seedkeeper's Network. CranberriesToday, cranberries are most often associated with Thanksgiving and New England, but cranberries are native to the northeast of North America and were used often by Indigenous peoples in those areas. Although a variety of cranberry is native to the bogs of Britain, and the Scandinavian lingonberries are a relative, the vast majority of modern cranberry consumption is based on species native to the U.S. and Canada. Maple Syrup & SugarMaple Syrup is one of the few sweeteners native to North America (honeybees, sugar cane, sorghum, and sugar beets are all imported). First used by Indigenous peoples in the Northeast, it is unclear which tribes first started use of maple sap as a sweetener. One Haudenosaunee/Iroquois legend indicates that the people first observed red squirrels cutting into the bark of maple trees and returning to drink the sap that flowed out. This has since been confirmed by scientific observation of squirrel behavior. Maple syrup and sugar was made either by freezing the water out of the sap, or by boiling with heated rocks. European colonists were quick to adopt maple sugaring as an important source of late winter calories and shelf-stable year-round sweetener. Although for some reason in the United States maple products are associated with fall, maple sugaring time is usually in March, when daytime temperatures rise above freezing, and fall below freezing at night - perfect conditions for optimum sap production. PapayaThe native range of the papaya is from southern Mexico to northern South America, although it has been naturalized throughout the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. With a quick maturity - some papaya can produce fruit after just one year - Europeans spread the plant to other tropical regions around the world where it is widely used in many different stages of ripeness, both cooked and raw. PeanutsThe archaeological record of peanut cultivation is not clear, but it is clear that it was present in Brazil and Central America in the 16th century when European explorers arrived in South America. The peanut is not actually a nut - it is a legume and more closely related to beans than, say, pecans. But its culinary importance grew once it was imported by Europeans to Africa and Asia. The peanut actually came to North America by way of enslaved Africans, who carried it with them as they were stolen from their homelands. The peanut was largely regarded as animal fodder by Europeans, and used in subsistence farming by enslaved Africans and African-Americans in the U.S. In the late 19th century, a number of people, including John Harvey Kellogg and Heinz, were filing patents for peanut-butter-like substances. Ironically, George Washington Carver, African-American plant scientist and the man most associated with peanut butter, didn't actually invent it. Today, about the only people who don't enjoy peanuts much are Europeans, which is ironic given their role in spreading them globally. PecanNative to North America, the pecan is one of my favorite nuts. Its native range ran from New England to Mexico and was widely used by Indigenous peoples. The word "pecan" likely comes from a 16th century European corruption of the Algonquian word "pacane," describing nuts that required stones to crack. Hickory nuts (also known as butternuts) and black walnuts are in the same family as pecans. PineappleAlthough most Americans associate pineapples with Hawaii, they are actually native to the Paraguay River basin, which stretches between modern-day Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina. Pineapples were cultivated by the Maya and Aztecs and Europeans first encountered them in the 15th century. Named the "pine apple" because of its resemblance to a pine cone and its status as a fruit, Europeans were able to grow some pineapples in greenhouses. In the 18th century, the pineapple was a symbol of hospitality and wealth and were much smaller than modern-day cultivars. Pineapple plantations were first installed by White Americans in Hawaii in the 1880s. James Dole made his fortune with pineapple plantations, processing, and canning innovations, which introduced the pineapple to ordinary Americans across the country. PotatoesWhat would Europe be without the potato? And yet, this starchy tuber, which spread throughout the Andes mountains prior to European contact, is originally from the border of modern-day Peru and Bolivia and dates back as far as 8,000 years ago. Cultivated from the wild tuber by Indigenous agriculturalists, over 5,000 varieties now exist. Potatoes were the staple crop of the Inca, who built their empire on it. Andean Indigenous peoples used it in all the usual ways, but also pioneered a special preservation technique called chuño, whereby the potatoes were frozen and dried in a way that made them very light and allowed them to keep for years. Chuño was usually prepared as part of a stew and was an important cash crop for Indigenous farmers. Prior to its introduction to Europe, most of the poorer classes relied on turnips and rutabaga for starchy bulk calories. But the potato was not only more palatable, it was more prolific, easier to grow, and it kept longer in storage. The shift to potatoes throughout Northern Europe in particular meant that the advent of potato blight in the mid-19th century, particularly in subjugated Ireland, started a mass migration of Europe's poor to the nations which had fed them so well for so long. QuinoaAlso native to the Andes and Peru, quinoa (pronounced "keen-wah"), is a member of the amaranth family. Used as a cereal crop by the Inca and other Indigenous peoples in the Andes mountains, quinoa has been in cultivation for as many as 5,000 years. When the Spanish arrived, determined to stamp out Incan culture, quinoa almost disappeared, but it persisted. Its "discovery" by White Americans interested in "superfoods," the price of this essential Indigenous grain actually skyrocketed. Whether or not this is good for Indigenous farmers is a matter of some debate, but when in doubt, be sure to buy from Indigenous producers. Squash & PumpkinAlong with corn and beans, squash make up the famous "Three Sisters" of Indigenous foodways. One of the oldest cultivated crops of the Americas, dating back as many as 10,000 years ago (before maize and beans), squashes are native to the Andes and Mesoamerica and wild varieties actually predate human inhabitation on the continents. Their cultivation was widespread throughout North and South America prior to European contact. All global varieties of squash, including pumpkins, zucchini, and decorative gourds, originated in the Americas. The word "squash" is an English corruption of the Narragansett word "askutasquash" meaning "a green thing eaten raw." Today, pumpkins (a word for a particular kind of large, round, orange squash that doesn't actually have an official classification) are mostly associated with Thanksgiving and New England foodways, although in the 19th century they were also stereotypically associated with slavery. They were one of the Indigenous foods featured in the first "American" cookbook, published by Amelia Simmons in 1796. SunflowerSunflowers are also native to North America, thought to have been cultivated near present-day Arizona and New Mexico around 3000 BC. Cultivated for their oily seeds and tuberous roots (also known as sunchokes or "Jerusalem artichokes"), sunflowers were also sometimes used as dyes. Although they were an important crop for Indigenous peoples, they were not in widespread use by European-Americans until their popularization in 19th century Russia, where they had been imported. Today, North and South Dakota are the biggest producers of sunflowers in the US and sunflower seeds, "sunbutter" and sunflower oil are popular modern uses. Not so much with the "sunchoke," although the tubers are regaining some popularity. Sweet PotatoSweet potatoes are native to Central America. Although called "potatoes" and sometimes "yams," they are not related to either plant. Sweet potatoes are more closely related to morning glory and bindweed. Sweet potatoes were spread across the Pacific nearly 400 years before Columbus by Polynesians, who brought the vine back with them. It was the Spanish and the Portuguese, however, who spread the sweet potato to the Philippines and Japan, respectively. The Spanish also brought the sweet potato to West Africa, where it was adopted, but not without some derision as its taste. The yam is native to Africa, which is likely why so many Americans, especially African-Americans, call sweet potatoes "yams." TomatoWhich is more authentic? Italian tomato sauce, or Mexican salsa? Hate to break it to you, but the Mexicans have the ayes on this one. Wild tomatoes are native to Western Mexico and were originally tiny, sour, and hard. Careful cultivation by Indigenous people led to thousands of more edible varieties, including husk tomatoes ranging from tomatillos to ground cherries. In Nahuatl (the Aztec language), "tomatl" was used to reference green tomatoes like tomatillos, and "xitomatl" was used for red varieties. The Spanish translated it as "tomate" and hence the term "tomato." When brought back to Europe, the bright red fruits were originally identified as a type of eggplant (both are members of the nightshade family), it garnered the nickname "love apple," and was originally considered poisonous. Although it was cultivated as a decorative plant, it was not in widespread use in Europe until the mid-18th century. It's widespread adoption in Italy was likely connected to nationalist sentiments in the 19th century and its association with the color red in the flag of Italian unification. In the United States, Thomas Jefferson may have helped popularize the tomato outside of the American southwest. And his relative by marriage, Mary Randolph, featured tomatoes in her Virginia Housewife cookbook, published in 1824. By the end of the 19th century, tomatoes became a popular American preserve, providing color, acidity, and sweetness to the typical American table. TurkeyIndigenous to North America, turkeys have been consumed by Indigenous peoples for centuries. Turkeys were domesticated in Mesoamerica as early as 800 BC. The Spanish brought back domesticated Aztec turkeys to Europe, where they quickly joined the European game bird lexicon. Associated with Christmas in Britain as early as the 17th century, the British Christmas goose persisted until the 20th century. In the United States, turkey is most commonly associated with Thanksgiving, although it is also often consumed at Christmas. Turkeys are one of the only indigenous American meat animals widely adopted in Europe and elsewhere. The name "Turkey" is likely associated with how Europeans were first introduced to turkeys - either through trade with the Middle East, or in association with guinea fowl as a game bird, introduced via Turkey. Domesticated turkeys are thought to have been descendants of Aztec domesticated birds reintroduced to North America via Europe. The turkeys purportedly eaten at the First Thanksgiving would have almost certainly been wild varieties, however. A shift to large scale commercial poultry production in the early 20th century has helped introduce turkey into the American diet through things like sliced deli turkey. The virtual disappearance of wild turkeys from New England due to deforestation meant that they had to be reintroduced to New England, an effort that began in the 1960s. VanillaVanilla is an orchid native to the Caribbean and south Central America. Cultivated by pre-Columbian Maya people, it was widely adopted by subsequent Indigenous peoples, including the Aztecs, who added it as a flavoring agent to their chocolate beverages. Attempts to cultivate vanilla in Europe were unsuccessful, largely because vanilla is naturally pollinated only by a native species of bee. An boy named Edmond Albius, enslaved on the Island of Reunion, pioneered a hand pollination technique that allowed vanilla to spread across the globe, including to the islands of Tahiti and Madagascar. Wild RiceWild rice, known in Anishinaabe/Ojibwe as "manoomin," is, indeed, a wild rice. Growing in marshy lakes, truely wild rice is harvested by hand from the wild. Wild rice is central to Anishinaabe culture, and one legend indicates that Ojibwe people emigrated from the Atlantic coast to the "place where food grows on the water." Although Northern wild rice is the most common, other two other varieties are native to North America - one in Florida and one in Texas. Suggestions to grow wild rice commercially were suggested as early as the mid-19th century, but it was not attempted on any scale until the 1950s. Commercially cultivated "wild" rice is now a great source of controversy, as is the genetic modification of wild rice. Opponents argue that commercial wild rice conflicts with Indigenous food sovereignty and treaty rights. True wild rice can also be endangered by relaxed water pollution standards, oil pipelines, and more. Indigenous people were rarely if ever involved in the research and are not beneficiaries of commercial varieties. For reasons of taste and to support Indigenous tribes and businesses, I strongly recommend that you source your wild rice from Indigenous producers. ConclusionPhew! That is a LOT of influential foods developed by Indigenous Americans. I hope you learned something with this catalog - I know I did. And I hope you'll support Indigenous food producers by purchasing direct whenever you can. Thanks to the magic of the internet, that's now possible more than ever. And for those of you interested, I'm planning a couple more posts (and a few talks) about the influence of pumpkins, corn, wild rice, and more. So stay tuned! What's your favorite Indigenous American food? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! If you found this article interesting, useful, and/or thought-provoking, join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

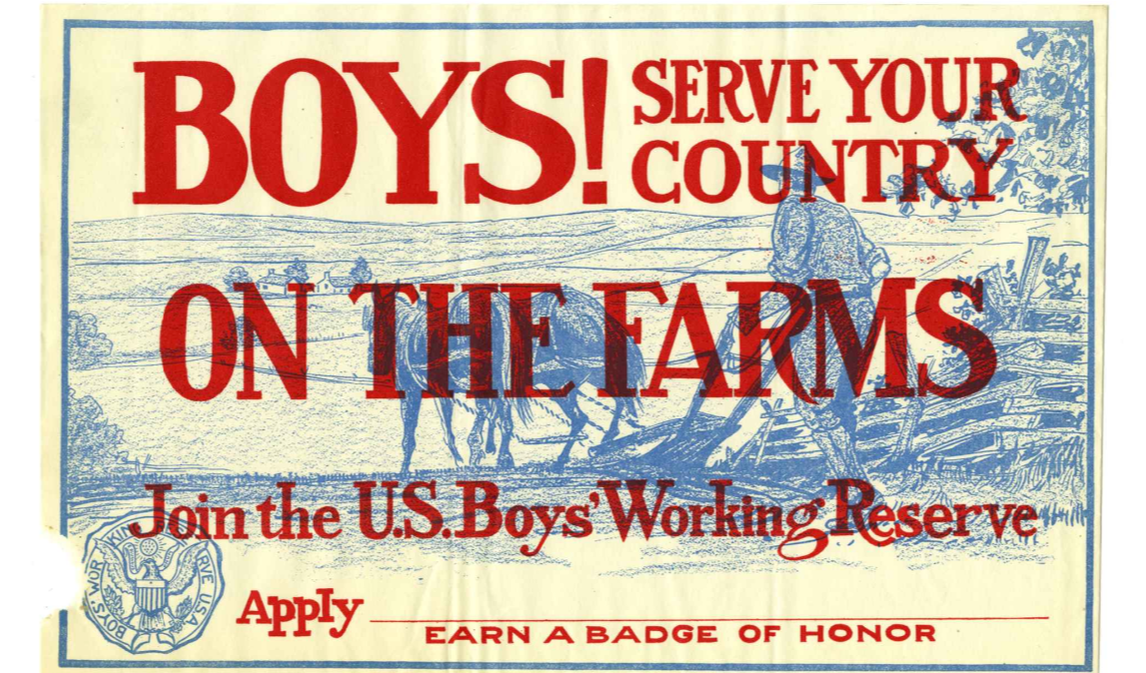

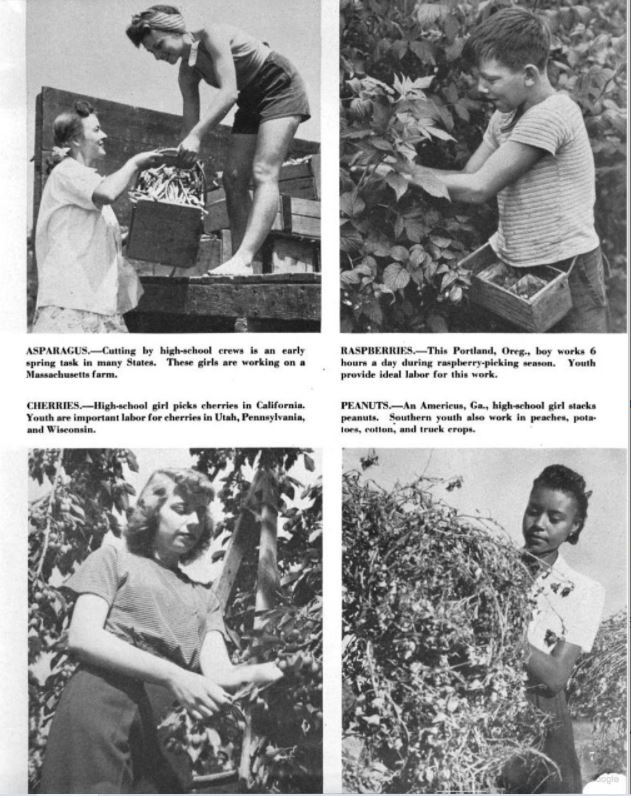

As we enter September (and FINALLY some cooler weather!) I always think of harvest time. Being immersed in finishing my book, I've been doing lots of reading about farm labor (and food preservation and war gardening and all those other fun topics), and Farm Cadets are a topic I've been researching to summarize in the book. During the First World War, very real fears about the food supply led to a whole host of changes to American agriculture, including farm labor. Although farmers lobbied Congress and President Wilson to exempt farmers and agricultural laborers from the draft, they were not exempted. So when the Selective Services Act was passed on May 18, 1917, farmers worried about who was going to harvest their crops. The wages of experienced farm hands began to skyrocket, and state and local governments scrambled to find a solution while the Federal government remained relatively hamstrung by the hold up of the Lever Act which would fund the U.S. Food Administration (and which would not be passed until August, 1917). Indeed, the U.S. Department of Labor would step in to help fill the gap in finding workers for many wartime labor needs. For American suffragists, the Woman's Land Army was a reasonable solution. But rural and agricultural folks are fairly conservative, and the idea of young city women in overalls (scandal!) working their fields was unpalatable for most. Teenaged boys, however, were a good solution, in the eyes of many. Not only were they out or nearly out of school during key planting and harvest times, organized labor camps would train them for military service. And indeed, that's how many of the farm cadet camps were organized - with military tents, uniforms, ranked officers, and military language. The reality of the practice, like that of the Woman's Land Army, was a bit more amorphous. I'm still sifting through the heady propaganda of newspaper articles and official reports versus what actually took place, but it looks like Farm Cadets, which appear to have included girls as well as boys, at least in New York State, did have a positive impact, particularly on fruit harvests, which often needs lots of dexterous manual labor for short periods of time. Gary E. Moore has written a nice overview of the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve, which was a US Department of Labor program started in June, 1917. You can also read a 1918 report from the Bureau of Educational Experiments (no really, that's what it's called), entitled "Camp Liberty: A Farm Cadet Experiment." The Farm Cadet program (like the Woman's Land Army and victory gardens) was revived for service during the Second World War. In 1947, following the war, the United States Department of Agriculture published, "Farm Work for City Youth," a glossy, photo-laden pitch for the value of agricultural labor, rebranded as "Victory Farm Volunteers." In New York State, I have found evidence that the Farm Cadet program lasted, under that name, as late as 1982. With a few unreachable references on Google Books to even further into the 1980s. The need for seasonal agricultural labor today is filled largely by migrant workers, many of whom work in appalling conditions and for poor wages. There have been improvements in recent years as various states implement minimum wage requirements for agricultural workers and mandate things like breaks, restroom facilities, and on-site water. But I wonder, if teenagers (especially white, middle class teenagers) continued to work in agricultural labor on their summers "off" - what would our agricultural labor landscape look like today? If you enjoyed this World War Wednesday history article, please consider joining us on Patreon, which offers special patrons-only perks.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed