|

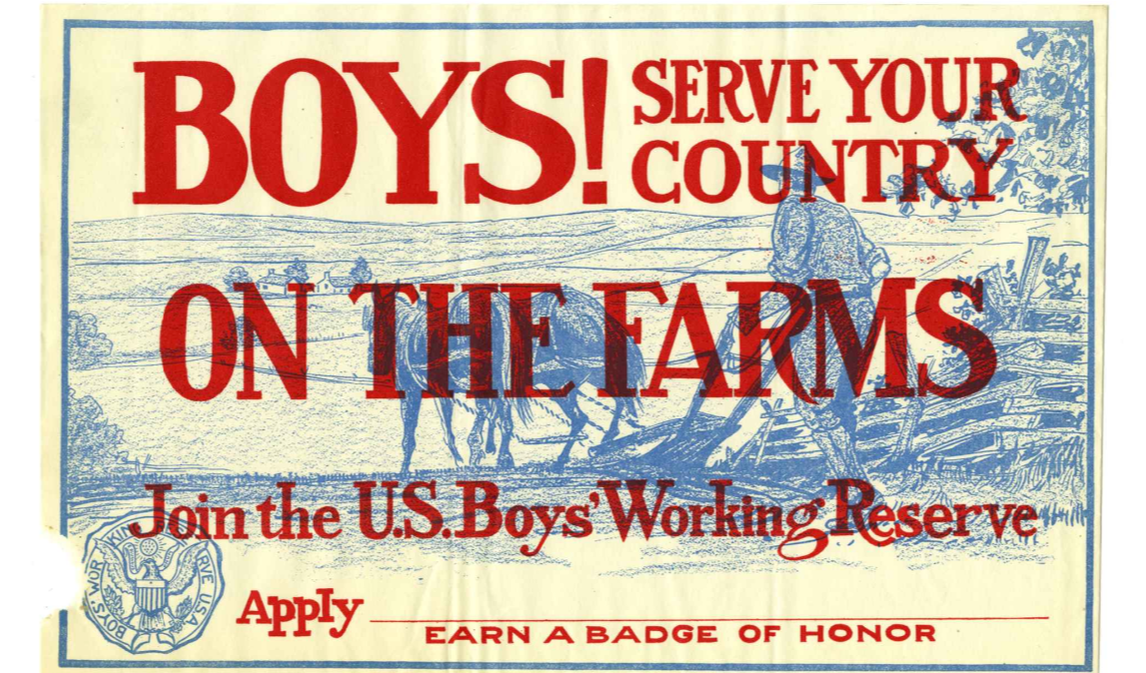

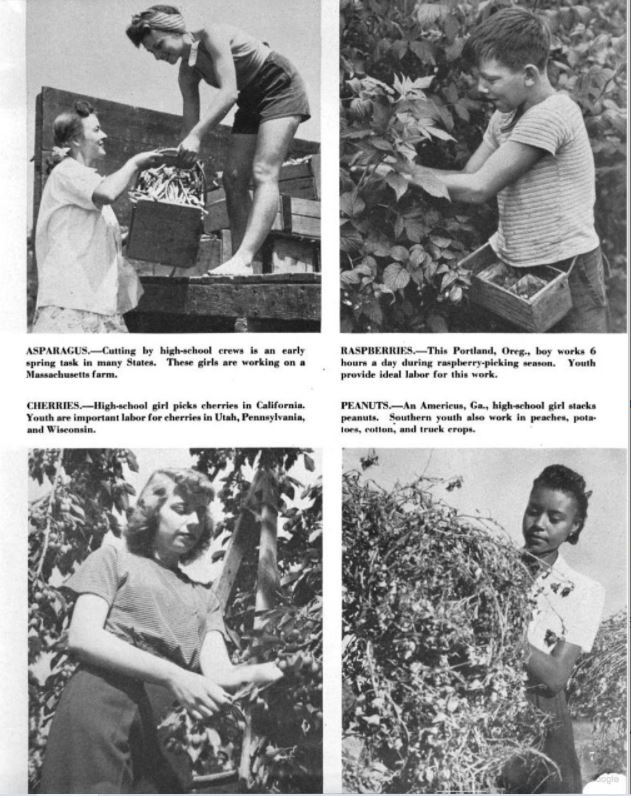

As we enter September (and FINALLY some cooler weather!) I always think of harvest time. Being immersed in finishing my book, I've been doing lots of reading about farm labor (and food preservation and war gardening and all those other fun topics), and Farm Cadets are a topic I've been researching to summarize in the book. During the First World War, very real fears about the food supply led to a whole host of changes to American agriculture, including farm labor. Although farmers lobbied Congress and President Wilson to exempt farmers and agricultural laborers from the draft, they were not exempted. So when the Selective Services Act was passed on May 18, 1917, farmers worried about who was going to harvest their crops. The wages of experienced farm hands began to skyrocket, and state and local governments scrambled to find a solution while the Federal government remained relatively hamstrung by the hold up of the Lever Act which would fund the U.S. Food Administration (and which would not be passed until August, 1917). Indeed, the U.S. Department of Labor would step in to help fill the gap in finding workers for many wartime labor needs. For American suffragists, the Woman's Land Army was a reasonable solution. But rural and agricultural folks are fairly conservative, and the idea of young city women in overalls (scandal!) working their fields was unpalatable for most. Teenaged boys, however, were a good solution, in the eyes of many. Not only were they out or nearly out of school during key planting and harvest times, organized labor camps would train them for military service. And indeed, that's how many of the farm cadet camps were organized - with military tents, uniforms, ranked officers, and military language. The reality of the practice, like that of the Woman's Land Army, was a bit more amorphous. I'm still sifting through the heady propaganda of newspaper articles and official reports versus what actually took place, but it looks like Farm Cadets, which appear to have included girls as well as boys, at least in New York State, did have a positive impact, particularly on fruit harvests, which often needs lots of dexterous manual labor for short periods of time. Gary E. Moore has written a nice overview of the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve, which was a US Department of Labor program started in June, 1917. You can also read a 1918 report from the Bureau of Educational Experiments (no really, that's what it's called), entitled "Camp Liberty: A Farm Cadet Experiment." The Farm Cadet program (like the Woman's Land Army and victory gardens) was revived for service during the Second World War. In 1947, following the war, the United States Department of Agriculture published, "Farm Work for City Youth," a glossy, photo-laden pitch for the value of agricultural labor, rebranded as "Victory Farm Volunteers." In New York State, I have found evidence that the Farm Cadet program lasted, under that name, as late as 1982. With a few unreachable references on Google Books to even further into the 1980s. The need for seasonal agricultural labor today is filled largely by migrant workers, many of whom work in appalling conditions and for poor wages. There have been improvements in recent years as various states implement minimum wage requirements for agricultural workers and mandate things like breaks, restroom facilities, and on-site water. But I wonder, if teenagers (especially white, middle class teenagers) continued to work in agricultural labor on their summers "off" - what would our agricultural labor landscape look like today? If you enjoyed this World War Wednesday history article, please consider joining us on Patreon, which offers special patrons-only perks.

1 Comment

Zeke Youcha

12/30/2023 05:24:18 pm

In 1943-44 I served as a farm cadet and then enlisted in the Navy in 1945. there is little on line about this endeavor in WW2. Where can I find it. Out of the several thousand students in my High School only about 7 of us became cadets. Our grades had to be high we missed several months a year of school attendance and never-the -less had to maintain our grades. It was hard work, but at 96, I still appreciate all that I learned working so hard for my country.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed