|

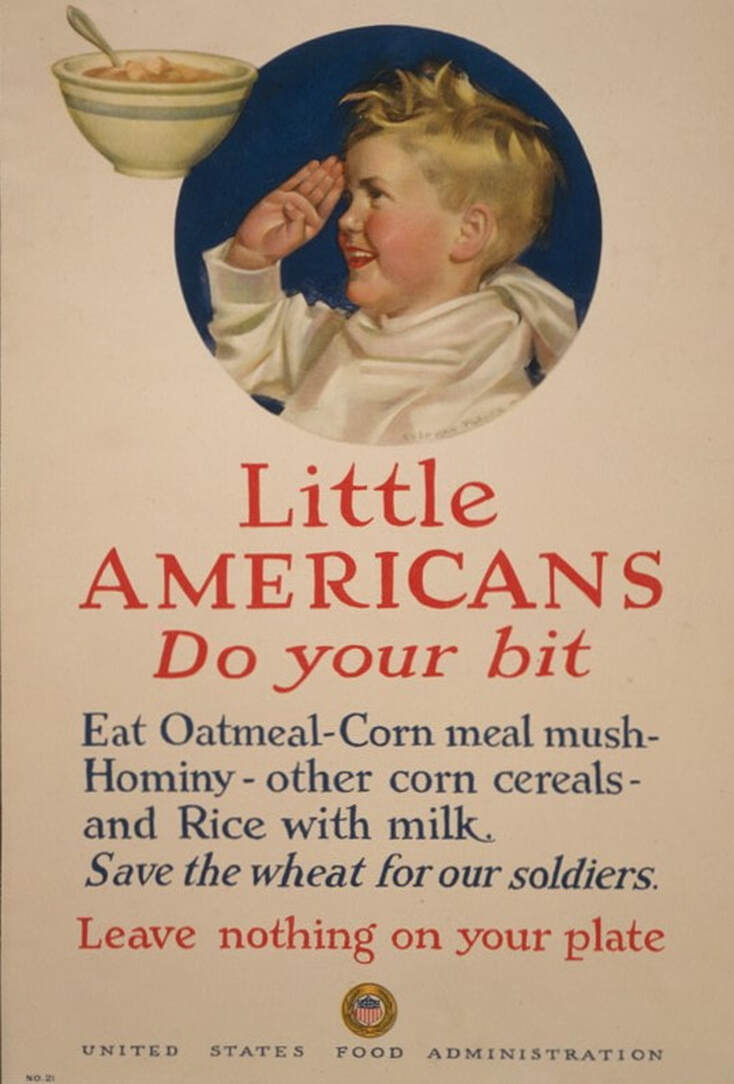

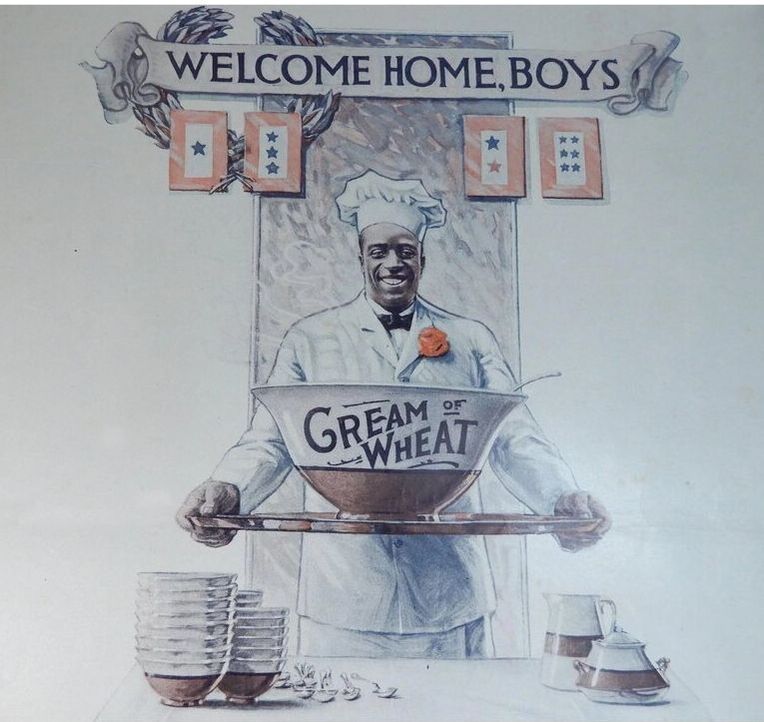

I was interviewed recently about breakfast cereals, especially corn flakes and the Kellogg brothers, so I thought for this week's World War Wednesday we'd take a look at this sweet propaganda poster from the First World War. "Little Americans - Do Your Bit! Eat Oatmeal - Corn meal mush - Hominy - other corn cereals - and Rice with milk. Save the wheat for our soldiers. Leave nothing on your plate" was designed by commercial artist Cushman Parker, who also designed covers featuring cherubic children for the Saturday Evening Post. This poster is interesting because the message is targeted specifically at children. Aside from the school garden movement, there weren't many food-related wartime posters directed to kids - this is one of the only ones. In this poster, a rosy-cheeked blond young man - who looks to be about five or six years old, salutes a floating bowl of hot cereal, a large white napkin tied around his neck as a bib. Although cold breakfast cereals were around at the time of the First World War, they were still considered less nourishing than hot cereals, especially for children. Oatmeal, Cream of Wheat (a.k.a. farina or semolina), and cornmeal or hominy mush were still popular at the breakfast table. Wheat was in short supply during the First World War, so ordinary Americans were encouraged to voluntarily restrict use to free up supplies for American soldiers and the Allies. That meant no more farina! As was true of much of the wartime propaganda, this poster calls for Americans to support the soldiers, doing without so "the boys over there" could have enough. Although Americans only entered the war in the spring of 1917, and it was over by the fall of 1918, wheat supplies continued to tighten throughout the war. By shifting eating habits to focus on other hot cereals, especially oatmeal and corn products like grits, Americans could help "do their bit" for the war effort. Rationing was voluntary for Americans, but Meatless Mondays and Wheatless Wednesdays still came to dominate American daily life. And children were no exception! Although advertising usually targeted the person who did the food shopping (usually the mother), this poster stands out as one targeting children directly, likely to help educate them about the needs of American troops and cut down on potential complaining, which might encourage parents to give into whining and purchase wheat products. The return of wheat, sugar, meat, and fats like butter and lard were a welcome herald to the end of the war. In this 1919 magazine advertisement, Rastus, the racist depiction of an African American cook used by Cream of Wheat packaging and advertisements for over 100 years before finally being removed in the fall of 2020, welcomes home American troops with an enormous bowl of Cream of Wheat - a sign of the end of rationing and likely an attempt to return Cream of Wheat to the tables of Americans who might have gotten used to eating other alternatives. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

2 Comments

This post contains Amazon affiliate links. Summer Kitchens Recipes and Reminiscences from Every Corner of Ukraine by Olia Hercules had been on my wish list for a while. Released in 2020, it seemed like just exactly the kind of cookbook I would like - interesting recipes linked with interesting stories. When Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, and Olia Hercules became a defacto spokesperson for Ukrainian foodways, I decided to finally purchase it. I'm quite picky about cookbooks, and it takes a lot to impress me. The recipes need to be familiar but surprising, introducing me to new techniques and especially flavor combinations. The headnotes have to be robust, the recipes not too finicky, and the storytelling excellent. Summer Kitchens manages to meet and exceed all of these requirements. It's really quite a stunning little book. Olia is just a year older than me, was born and spent most of her childhood in Ukraine. At age 12 her family moved to Cyprus for her asthma, and as a young adult she moved to London to study, where she lives today. She started her career in film, and it shows through her storytelling. She also worked as a professional chef, including for Ottolenghi's. Summer Kitchens is her third cookbooks. Her first, Mamushka: Recipes from Ukraine and Eastern Europe, was published in 2015, and her second, Kaukasis The Cookbook: The culinary journey through Georgia, Azerbaijan & beyond, was published in 2017. Her fourth cookbook, Home Food: Recipes to Comfort and Connect, is due to be released in December of this year. Although I haven't read her earlier cookbooks, I did have the opportunity to flip through Mamushka in a bookstore the other day, and I have to admit it wasn't as appealing as Summer Kitchens. I think that's in part because Summer Kitchens is all about that indefinable longing for a home you only knew for a little while. Like Olia, and many of the authors of letters she includes in the back of the book, I have memories of rural idylls as a child. Mine were of visiting my great-grandmothers in rural North Dakota in the summer. Of enormous gardens where I learned that peas actually aren't so bad if you eat them fresh and sweet right from the pod. Of old-fashioned flowers, and dirt cellars full of glass jars of preserved food. Of freshly-turned black dirt in the potato patch so soft it was perfect for bare feet to make impressions. Of homemade baked beans (my first ever taste) and fat, nutmeg-scented donuts and homemade pickles and sweet water buns with bright red chokecherry jelly. Of rhubarb custard cakes and the world's best North Dakota red mashed potatoes. Of playing beneath enormous cottonwood trees with their rustling leaves, and searching the quiet gravel roads for agates and quartz and petrified wood. Olia's reminiscences are a little different, but they still resonate. Sunny days in gardens, preserving food for winter, helping grandmas and moms clean fruit and chop vegetables. Memories of delicious homemade foods, special holidays, and especially the pich - the enormous brick and tile stoves that are common in many northeastern European countries, including my ancestral Scandinavia. The cookbook itself is divided seven chapters of recipes, preceded by essays on the summer kitchen and Ukraine's unique food regions. The chapters are:

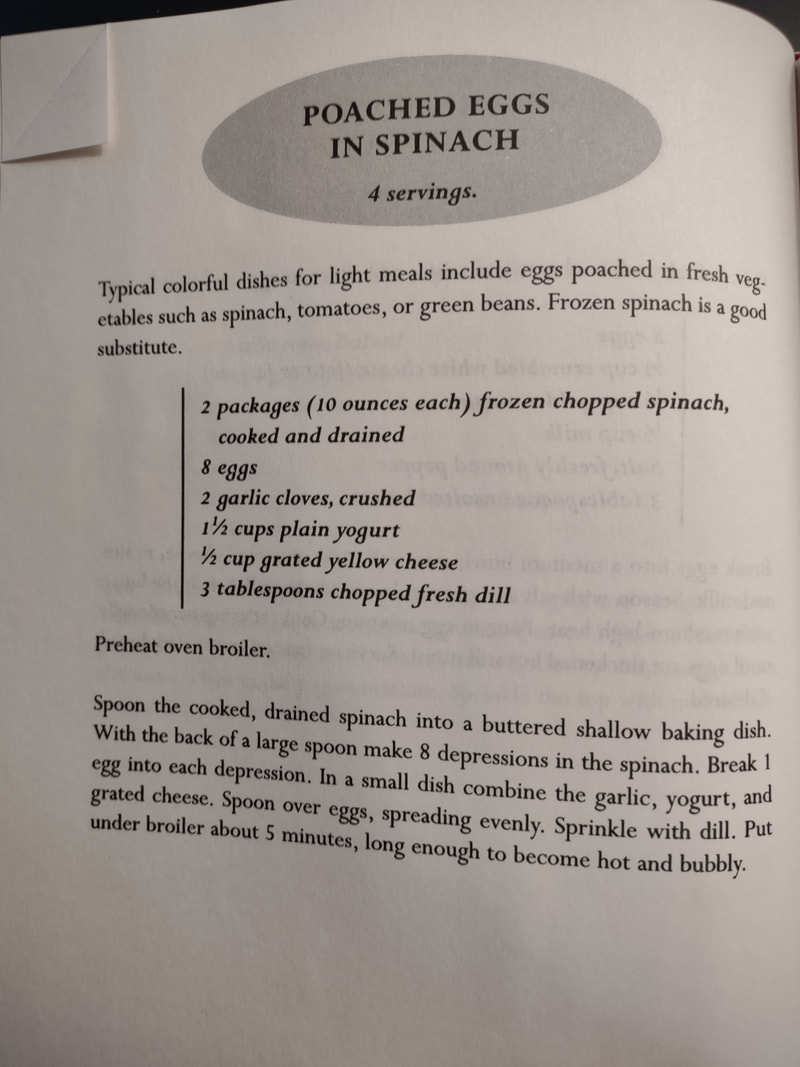

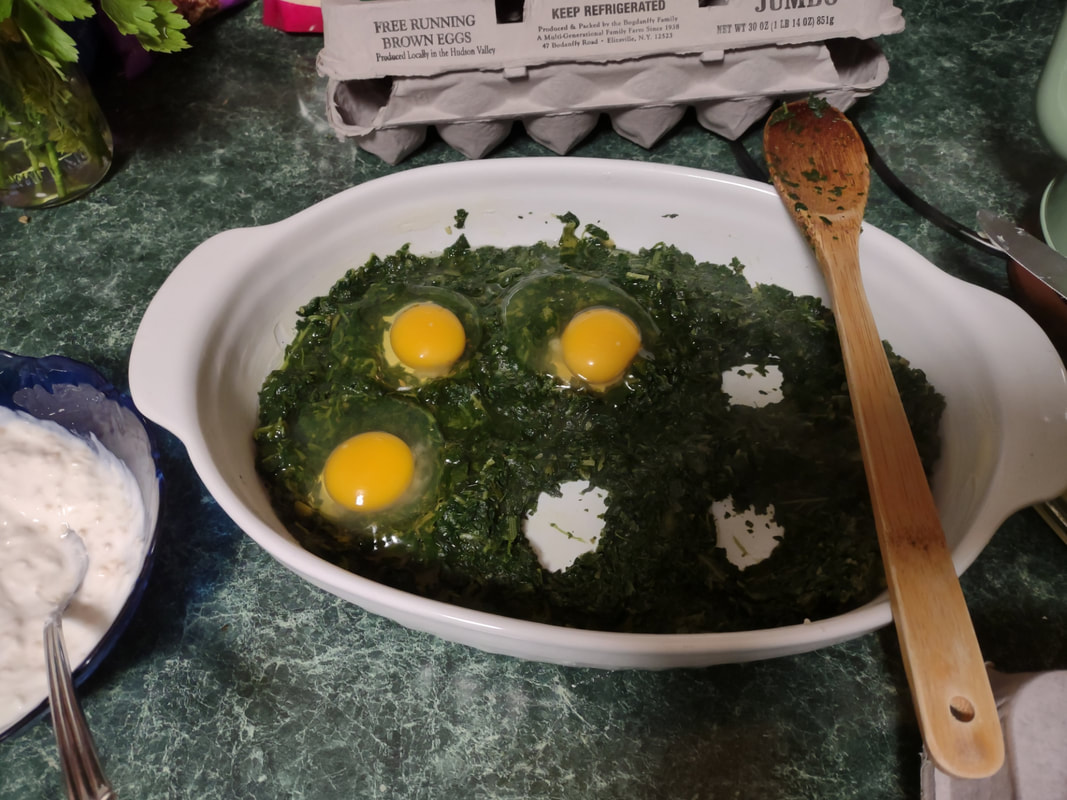

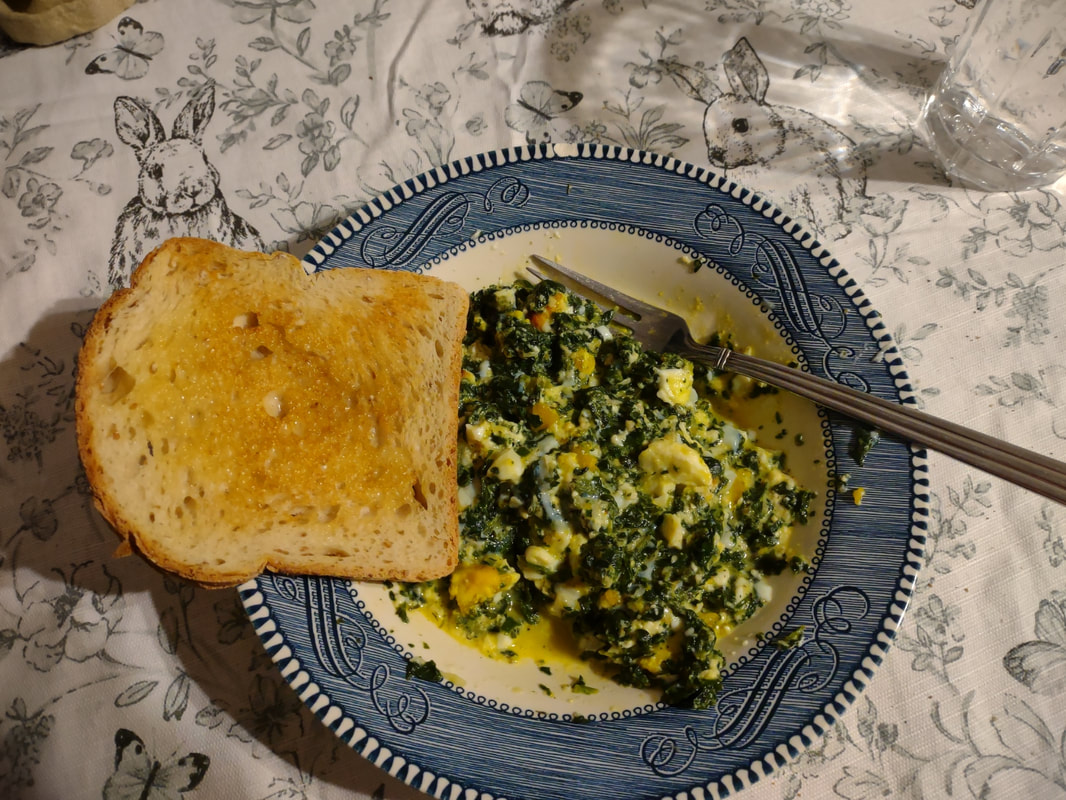

Although the chapter on fermenting will likely make Americans flinch slightly (Summer Kitchens was published in the UK, which apparently does not have as stringent rules about food preservation advice as the U.S.), the recipes sound amazing, and several don't require preservation at all, including the intriguing-sounding smoked pears (and plums). I was interested to see that Hercules included watermelon molasses in the cookbook. Her headnotes indicate that she included it more for posterity than for anyone to use it, but sweet watermelon paste is still used in some areas of North Dakota, where Germans from Russia immigrants left Ukraine for the Northern Plains. Although it is definitely not a vegetarian cookbook, many of the recipes are vegetarian. This reflects in part the background of the people who developed this cuisine - meat was not always abundant, and vegetables often were. But also, as Hercules mentions, her husband is vegetarian, as are many of her friends, and so she cooks vegetarian often. This was incredibly refreshing for me to see. I am not vegetarian, but enjoy vegetarian food and am always looking for new recipes. Some, like cucumbers in sour cream are familiar. Others, like a tomato mulberry salad with red onion and purple basil are stunningly beautiful and sound delicious. Even the meat recipes, which I usually find boring in most cookbooks, are inviting, like the slow-roasted pork with sauerkraut and dried fruit. Fatty pork gets rubbed with spices and then cooked slowly in the oven with sliced onion, sauerkraut (homemade, of course), prunes, dried apricots, apples, and toasted caraway, coriander, and fennel seeds. Olia recommends fending off greedy guests to ensure enough leftovers to stuff into a sweet bun recipe also included in the cookbook. With the exception of pistachio napoleons and poppyseed babka, the dessert recipes are also unfussy and delicious-looking. A caramelized apple ricotta cake, classic potato-dough dumplings stuffed with halved plums and served with honey, steamed bilberry-stuffed donuts rolled in crushed walnuts and sugar. Summer Kitchens is not just about summer cooking. It is about how summer kitchens have been used throughout Ukraine historically, how they continue to be used, and what they represent. It's no accident that Hercules starts her book in September, with preserving season. Because the summer kitchen is also a reflection of the summer garden. Many recipes, especially in the first chapter, reflect an abundance of produce that most of us no longer have access to. Hercules even notes this change in her essays, noting in one how dismayed a young Ukrainian was to find her uncle had dropped a forty pound sack of cucumbers off on her front step. Instead of joy at the opportunity to turn free produce into pickles, the young woman saw only work and the guilt to do something with the cucumbers before they went bad. And therein lies the rub. While Hercules has managed to produce an amazingly atmospheric and even cozy cookbook full of recipes any home cook with a little ambition could produce, it is also a love letter to a way of life many would say is dying. Hercules herself admits that her beloved pich ovens are increasingly being torn out for more modern appliances, and summer kitchens are being converted or torn down. It's easy to romanticize the past, to the frustration of those trying to still live it. But in a day and age when whole generations dream of giving up the rat race and settling in a little rural cottage with a big garden, Olia Hercules' depictions of Ukraine can sound like paradise. And perhaps it is. But in a time when Ukraine is being torn apart by war (again) and threatened with hunger (again), Summer Kitchens reads more like a love letter to what every Ukrainian would love to have, but can never seem to grasp for long. Serfdom, World Wars, collectivism, famine, invasion, Sovietization - all these have threatened but never quite destroyed the Ukrainian garden of Eden. But like most old foodways, Ukrainian food is threatened by modernity. I'm hopeful that books like Summer Kitchens will help keep them alive. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! If you'd like to learn more about Ukraine, food history, and politics, check out my new Substack newsletter - Historical Supper Club. Note: This article contains Amazon Affiliate links. As I'm sure many of you have, I've been thinking a lot about Ukraine and Eastern Europe these days. Last week I launched a Substack specifically so I could give food history commentary on current events, and my first post was all about Ukraine. I've long had an interest in the cuisines of Eastern Europe and the states of the former Russian/Soviet empires. Their creative use of ordinary ingredients and emphasis on fresh fruits and vegetables is extremely appealing to a Midwesterner raised on meat and potatoes. The connection to the land, gardens, and older folks also reminds me a lot of visiting my great-grandmothers in rural North Dakota, who kept huge gardens, and dirt cellars full of preserved foods. I'm always on the lookout for new cookbooks in this vein, so when I saw the following, I snatched it up. The week before the Russian invasion of Ukraine - Cuisines of the Caucasus Mountains: Recipes, Drinks, and Lore from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Russia by Kay Shaw Nelson arrived at my door. First published in 2002, it's written by Nelson, an American who studied Russian language and literature and later became enamored of the food of Georgia (which I am also very interested in). She covers the whole of the Caucasus Mountains, and writes eloquently on each country and their regional differences in agriculture, wild foods, terrain, and foodways. I'm always interested in vegetarian dishes, and this cookbook has quite a few, in addition to some delicious-sounding meat dishes. The book is divided by a combination of meal and ingredient, including appetizers, soups, dairy dishes (where eggs are confusingly included), fish, meat/poultry/game, vegetables & salads, grains & legumes, breads/pastas/savory pastries, desserts & sweets, and beverages/drinks/wine. I have earmarked a number of dishes, including salads and egg-based dishes. After the success of Eggs en Cocotte last week, I thought we'd take a stab at another egg dish for a simple supper. Nelson doesn't assign this dish to a country or region, like she does the others, so I've ascribed it to the entire Caucasus Mountains region. Poached Eggs in Spinach with Garlic and YogurtNelson's original "Poached Eggs in Spinach" recipe is pretty straightforward, and as she remarks in the headnotes, tomatoes and green beans are an alternative vehicle for the poached eggs (similar to Middle Eastern shakshuka). However, her recipe leaves a bit to be desired. Because spinach is the main vehicle of this dish, if you don't season the cooked greens and the eggs well, it will be a flop. Here's my adaptation of her original recipe. 2 packages frozen spinach (10 ounces each), cooked and drained salt, pepper, and whatever other spices you like lemon juice 6 eggs 1 1/2 cups plain yogurt 2 garlic cloves, finely chopped 1/2 cup shredded mozzarella salt pepper dried dill butter for the baking dish Preheat your broiler. Season the spinach with salt, pepper, and lemon juice. Place in a well-buttered baking dish (not glass, which is not broiler safe) and make six indentations for the eggs. Mix the yogurt, garlic, and mozzarella. Crack the eggs into the indentations, then spread the yogurt evenly over the top (I skimped mine a little because I was using fewer eggs, and shouldn't have). Top the yogurt with more salt and pepper and dried dill. Broil for 10-15 minutes or until the yogurt is bubbly and browned and the egg whites are set. Two eggs per person was plenty, and the leftovers weren't bad, although the egg will obviously cook more once you reheat it. I ate mine all mixed up with some buttered cracked wheat toast (Heidelberg Bread Company in New York makes the BEST toast). This turned out pretty well, all things considered. Without the seasoning it would have been especially bland, so make sure you season your greens! A few things I would change - press more of the water out of the spinach and add more lemon juice, add chopped fresh dill and parsley to the spinach mix, or lemony fresh sorrel if I could find it. I think I would also add onion or more garlic to the spinach itself, instead of just the topping. I would also follow the instructions and use more yogurt for the topping - the places where the egg white wasn't covered it got a little tough in the oven. I think I would still stick with just six eggs, instead of eight, because it was a nice ratio of egg-to-spinach, so the spinach felt like a substantial part of the meal, instead of a garnish for the eggs. I might also try this again in a stovetop-safe vessel like a cast iron skillet, or pre-heat the spinach in the oven before adding the eggs. The bottoms of the eggs were still a little undercooked and the tops were a bit tough. That being said, this was a surprisingly satisfying dish, and anything that gets more dark leafy greens into the diet is always a good thing. I would definitely try this again, but with some changes to make it more flavorful. What do you think - would you try it? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Tip Jar

$1.00 - $20.00

Like what you read, watch, or hear? Wanna help support The Food Historian, but don't want to commit to a monthly thing, or sign up for Patreon? Then you're in luck! You can leave a tip! This one-time (non-tax-deductible) donation helps keep The Food Historian going and pays for things like webhosting, Zoom, additions to the cookbook library, and helps compensate Sarah for her time and energy in helping everyone learn more about the history of food, agriculture, cooking, and more. Thank you! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed