|

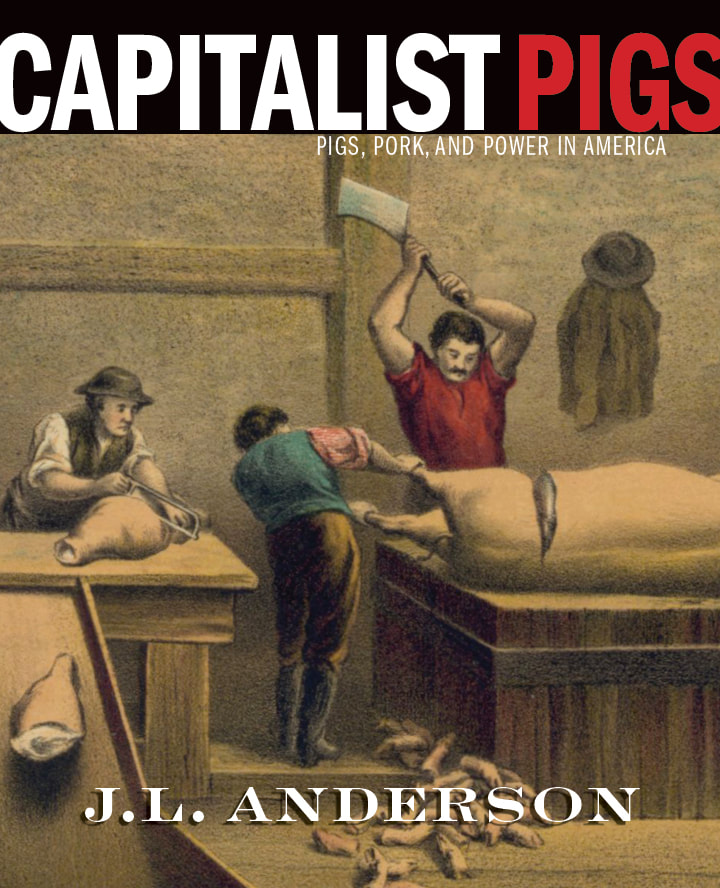

Okay folks, just 6 months after submitting and 9 months after receiving the invitation and book, my review of Capitalist Pigs is finally in print in the latest issue of Agricultural History - the journal of the Agricultural History Society. It's a pretty great issue, so I recommend you check out the few articles they have put up online. Alas, my review is not one of them, BUT! Being the rebel that I am, and seeing that I wrote this review for free (albeit in exchange for an advanced copy of the book, which was pretty cool), I'm going to do you a solid and post it here for you to read for yourself. For photographic proof, click through the images above! Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America. By J.L. Anderson. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2018. 300 pp., $34.99, paperback, ISBN 978-1-946684-73-8. “Capitalist pigs” is a term most frequently attributed to stereotypical Soviet protagonists describing Americans, or perhaps fat hogs in suits and top hats representing greedy businessmen in political cartoons. But in Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America, J.L. Anderson puts a clever turn on the phrase as he explores the role of pigs and pork in America from the early Colonial period to the present. In Capitalist Pigs, Anderson argues that hogs have played a unique role in the development of the United States, and that the United States played a unique role in the development of the hog. “Americans maximized opportunities for the proliferation of the hog, even amid changing values and ideals about empire, agriculture, cities, and health.” (5). In particular, Anderson emphasizes that the story of the hog in America is one of excess, as farmers and marketers alike attempted to “transcend limits” on production. Capitalist Pigs covers the Colonial period to the present in the United States and is organized thematically rather than chronologically. Anderson covers such topics as free-range hogs and their influence on early settlements, pork consumption and its shifting role from frontier and working class food to re-branded “other white meat,” early industrialization of pork production and husbandry, including a discussion of hog cholera and enclosure, the role of the hog as garbage disposal, from our earliest urban areas to the industrialized present, and finally with a discussion of the modern industrialization of the hog, including changing its very physique to match modern consumer tastes and the controversial rise of confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Capitalist Pigs is well-researched and the broad chronology of the book provides a sweeping view of the influence of the hog on American culture and development throughout the centuries, giving needed context to historians of all stripes. Anderson is at his most compelling when he includes the voices of marginalized people and his sections on indigenous populations, enslaved people, and the Civil Rights movement are among his best. For urban and environmental historians, the discussion of the role of hogs in reshaping the landscape and the transition of urban spaces to exclude them, even as they continued to operate as waste disposal systems, will be of particular interest. Twentieth century historians, particularly agriculture historians, will be impressed by his discussion of the industrialization of hog production and marketing from the 1940s on. Anderson’s background as a public historian means his writing is clear, straightforward, and free of jargon and unnecessarily convoluted sentences. His writing style is engaging and would appeal to not only professional historians, but likely students and laypeople as well. Although Anderson’s writing style is clear, his main arguments are not. It seems as though Anderson could not quite decide whether to write Capitalist Pigs as a more technical agricultural history, or as a social history, and decided to split the difference. Anderson notes the influence of pigs in the institution of slavery, subsistence farms, and as a “mortgage lifter.” But the primary argument outlined in the introduction is focused instead on how Americans changed the pig. An interesting, if somewhat divergent take from the usual social history bent of most food histories, the argument is ultimately a weak one. Although Anderson discusses extensively in the latter half of the book how farmers industrialized and economized pork production and even changed the body shape of pigs to accommodate changing consumer tastes, he spends little time discussing the effects on the pigs themselves. Although breeding is mentioned frequently, the only mention of any particular breed in the entire book is about how heritage breeds have become more fashionable in modern nose-to-tail cuisine and sustainable agriculture (172-73), despite the fact that discussing the various breeds of pig throughout the book would have lent weight to later industrial changes and changing consumer tastes. He also skirts around the effects of industrialization on the hogs themselves - only in a photo caption does he mention accusations of cruelty in hog confinement operations (201). In addition, although the title and discussions in several chapters imply that hogs played a significant role in building America’s capitalist system, Anderson does not quite make those connections clear throughout the chapters, and discussion of meat-packing beyond the 1850s is conspicuously absent. Given the influential role of America’s meat-packers in the late nineteenth century in both industrial capitalism and union history, this is a curious oversight. Although Capitalist Pigs doesn’t quite live up to the premise of its fantastic title, it is a worthy combination of agriculture and food history - combining the history of industrial technology and consumer uses of hogs throughout the entirety of American history. Food and agriculture historians in particular will find much of use, but American social, environmental, rural, urban, and Civil War historians will also enjoy the read. If you enjoyed this book review, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

2 Comments

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed