|

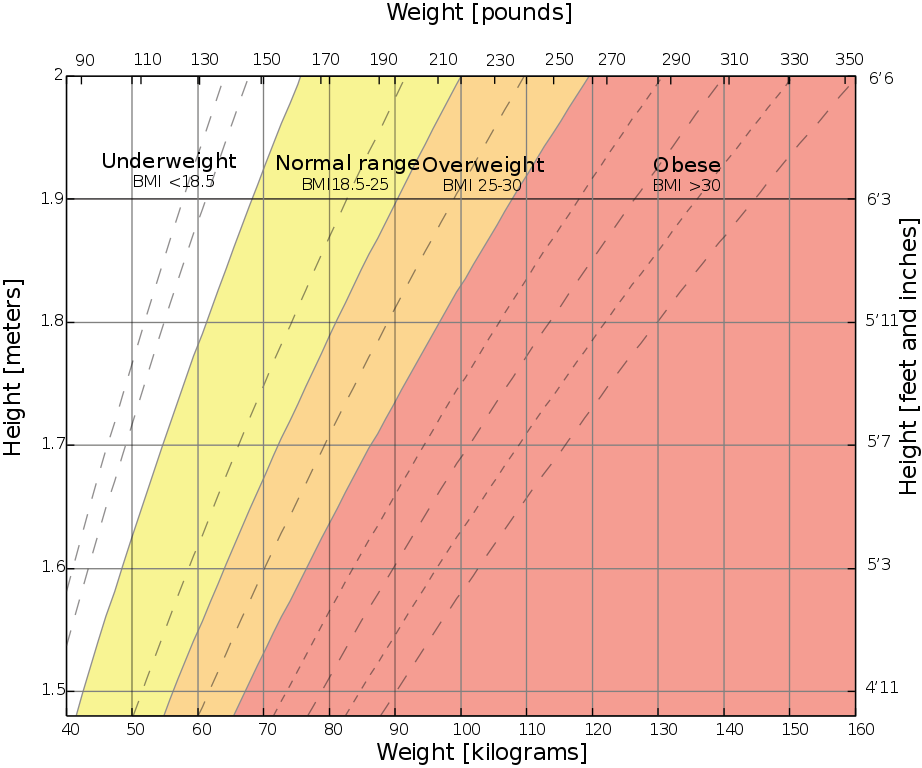

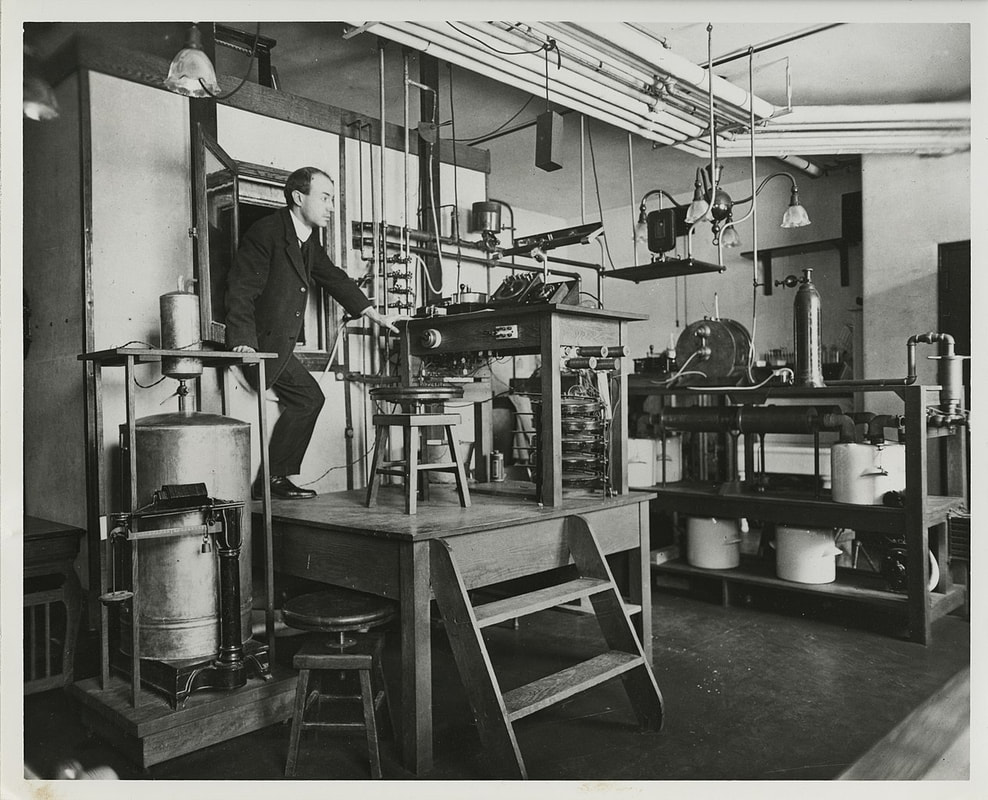

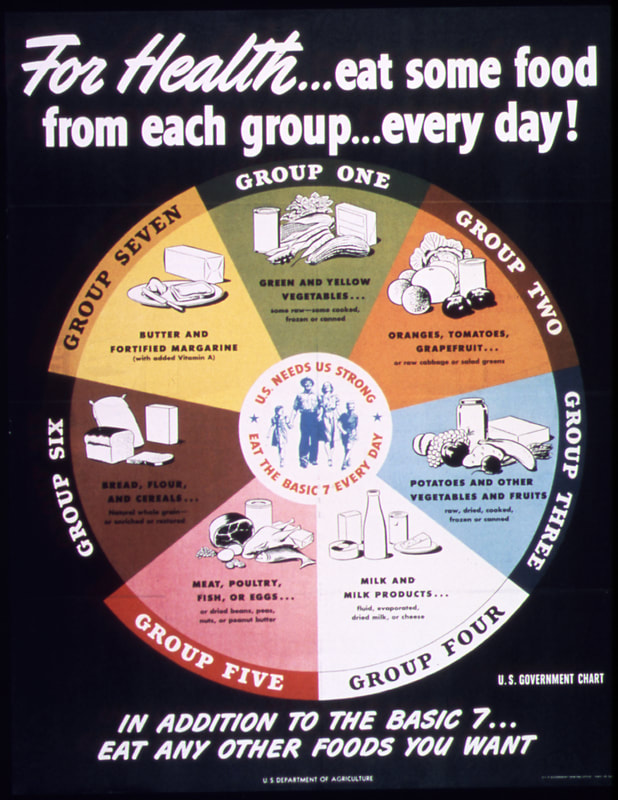

The short answer? At least in the United States? Yes. Let's look at the history and the reasons why. I post a lot of propaganda posters for World War Wednesday, and although it is implied, I don't point out often enough that they are just that - propaganda. They are designed to alter peoples' behavioral patterns using a combination of persuasion, authority, peer pressure, and unrealistic portrayals of culture and society. In the last several months of sharing propaganda posters on social media for World War Wednesday, I've gotten a couple of comments on how much they reflect an exclusively White perspective. Although White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture was the dominant culture in the United States at the time, it was certainly not the only culture. And its dominance was the result of White supremacy and racism. This is reflected in the nutritional guidelines and nutrition science research of the time. The First World War takes place during the Progressive Era under a president who re-segregated federal workplaces that had been integrated since Reconstruction. It was also a time when eugenics was in full swing, and the burgeoning field of nutrition science was using racism as justifications for everything from encouraging assimilation among immigrant groups by decrying their foodways and promoting White Anglo-Saxon Protestant foodways like "traditional" New England and British foods to encouraging "better babies" to save the "White race" from destruction. Nutrition science research with human subjects used almost exclusively adult White men of middle- and upper-middle class backgrounds - usually in college. Certain foods, like cow's milk, were promoted heavily as health food. Notions of purity and cleanliness also influenced negative attitudes about immigrants, African Americans, and rural Americans. During World War II, Progressive-Era-trained nutritionists and nutrition scientists helped usher in a stereotypically New England idea of what "American" food looked like, helping "kill" already declining regional foodways. Nutrition research, bolstered by War Department funds, helped discover and isolate multiple vitamins during this time period. It's also when the first government nutrition guidelines came out - the Basic 7. Throughout both wars, the propaganda was focused almost exclusively on White, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans. Immigrants and African Americans were the target of some campaigns for changing household habits, usually under the guise of assimilation. African Americans were also the target of agricultural propaganda during WWII. Although there was plenty of overt racism during this time period, including lynching, race massacres, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and more, most of the racism in nutrition, nutrition science, and home economics came in two distinct types - White supremacy (that is, the belief that White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values were superior to every other ethnicity, race, and culture) and unconscious bias. So let's look at some of the foundations of modern nutrition science through these lenses. Early Nutrition ScienceNutrition Science as a field is quite young, especially when compared to other sciences. The first nutrients to be isolated were fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fats were the easiest to determine, since fat is visible in animal products and separates easily in liquids like dairy products and plant extracts. The term "protein" was coined in the 1830s. Carbohydrates began to be individually named in the early 19th century, although that term was not coined until the 1860s. Almost immediately, as part of nearly any early nutrition research, was the question of what foods could be substituted "economically" for other foods to feed the poor. This period of nutrition science research coordinated with the Enlightenment and other pushes to discover, through experimentation, the mechanics of the universe. As such, it was largely limited to highly educated, White European men (although even Wikipedia notes criticism of such a Euro-centric approach). As American colleges and universities, especially those driven by the Hatch Act of 1877, expanded into more practical subjects like agriculture, food and nutrition research improved. American scientists were concerned more with practical applications, rather than searching for knowledge for knowledge's sake. They wanted to study plant and animal genetics and nutrition to apply that information on farms. And the study of human nutrition was not only to understand how humans metabolized foods, but also to apply those findings to human health and the economy. But their research was influenced by their own personal biases, conscious and unconscious. The History of Body Mass Index (BMI)Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a result of that same early 19th century time period. It was invented by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet in the 1830s and '40s specifically as a "hack" for determining obesity levels across wide swaths of population, not for individuals. Quetelet was a trained astronomist - the one field where statistical analysis was prevalent. Quetelet used statistics as a research tool, publishing in 1835 a book called Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, the English translation of which is usually called A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. In it, he discusses the use of statistics to determine averages for humanity (mainly, White European men). BMI became part of that statistical analysis. Quetelet named the index after himself - it wasn't until 1972 that researcher Ancel Keys coined the term "Body Mass Index," and as he did so he complained that it was no better or worse than any other relative weight index. Quetelet's work went on to influence several famous people, including Francis Galton, a proponent of social Darwinism and scientific racism who coined the term "eugenics," and Florence Nightingale, who met him in person. As a tool for measuring populations, BMI isn't bad. It can look at statistical height and weight data and give a general idea of the overall health of population. But when it is used as a tool to measure the health of individuals, it becomes extremely flawed and even dangerous. Quetelet had to fudge the math to make the index work, even with broad populations. And his work was based on White European males who he considered "average" and "ideal." Quetelet was not a nutrition scientist or a doctor - this "ideal" was purely subjective, not scientific. Despite numerous calls to abandon its use, the medical community continues to use BMI as a measure of individual health. Because it is a statistical tool not based on actual measures of health, BMI places people with different body types in overweight and obese categories, even if they have relatively low body fat. It can also tell thin people they are healthy, even when other measurements (activity level, nutrition, eating disorders, etc.) are signaling an unhealthy lifestyle. In addition, fatphobia in the medical community (which is also based on outdated ideas, which we'll get to) has vilified subcutaneous fat, which has less impact on overall health and can even improve lifespans. Visceral fat, or the abdominal fat that surrounds your organs, can be more damaging in excess, which is why some scientists and physicians advocate for switching to waist ratio measurements. So how is this racist? Because it was based on White European male averages, it often punishes women and people of color whose genetics do not conform to Quetelet's ideal. For instance, people with higher muscle mass can often be placed in the "overweight" or even "obese" category, simply because BMI uses an overall weight measure and assumes a percentage of it is fat. Tall people and people with broader than "ideal" builds are also not accurately measured. The History of the CalorieAlthough more and more people are moving away from measuring calories as a health indicator, for over 100 years they have reigned as the primary measure of food intake efficiency by nutritionists, doctors, and dieters alike. The calorie is a unit of heat measurement that was originally used to describe the efficiency of steam engines. When Wilbur Olin Atwater began his research into how the human body metabolizes food and produces energy, he used the calorie to measure his findings. His research subjects were the White male students at Wesleyan University, where he was professor. Atwater's research helped popularize the idea of the calorie in broader society, and it became essential learning for nutrition scientists and home economists in the burgeoning field - one of the few scientific avenues of study open to women. Atwater's research helped spur more human trials, usually "Diet Squads" of young middle- and upper-middle-class White men. At the time, many papers and even cookbooks were written about how the working poor could maximize their food budgets for effective nutrition. Socialists and working class unionists alike feared that by calculating the exact number of calories a working man needed to survive, home economists were helping keep working class wages down, by showing that people could live on little or inexpensive food. Calculating the calories of mixed-food dishes like casseroles, stews, pilafs, etc. was deemed too difficult, so "meat and three" meals were emphasized by home economists. Making "American" FoodEfforts to Americanize and assimilate immigrants went into full swing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as increasing numbers of "undesirable" immigrants from Ireland, southern Italy, Greece, the Middle East, China, Eastern Europe (especially Jews), Russia, etc. poured into American cities. Settlement workers and home economists alike tried to Americanize with varying degrees of sensitivity. Some were outright racist, adopting a eugenics mindset, believing and perpetuating racist ideas about criminology, intelligence, sanitation, and health. Others took a more tempered approach, trying to convince immigrants to give up the few things that reminded them of home - especially food. These often engaged in the not-so-subtle art of substitution. For instance, suggesting that because Italian olive oil and butter were expensive, they should be substituted with margarine. Pasta was also expensive and considered to be of dubious nutritional value - oatmeal and bread were "better." A select few realized that immigrant foodways were often nutritionally equivalent or even superior to the typical American diet. But even they often engaged in the types of advice that suggested substituting familiar ingredients with unfamiliar ones. Old ideas about digestion also influenced food advice. Pickled vegetables, spicy foods, and garlic were all incredibly suspect and scorned - all hallmarks of immigrant foodways and pushcart operators in major American cities. The "American" diet advocated by home economists was highly influenced by Anglo-Saxon and New England ideals - beef, butter, white bread, potatoes, whole cow's milk, and refined white sugar were the nutritional superstars of this cuisine. Cooking foods separately with few sauces (except white sauce) was also a hallmark - the "meat and three" that came to dominate most of the 20th century's food advice. Rooted in English foodways, it was easy for other Northern European immigrants to adopt. Although French haute cuisine was increasingly fashionable from the Gilded Age on, it was considered far out of reach of most Americans. French-style sauces used by middle- and lower-class cooks were often deemed suspect - supposedly disguising spoiled meat. Post-Civil War, Yankee New England foodways were promoted as "American" in an attempt to both define American foodways (which reflected the incredibly diverse ecosystems of the United States and its diverse populations) and to unite the country after the Civil War. Sarah Josepha Hale's promotion of Thanksgiving into a national holiday was a big part of the push to define "American" as White and Anglo-Saxon. This push to "Americanize" foodways also neatly ignores or vilifies Indigenous, Asian-American, and African American foodways. "Soul food," "Chinese," and "Mexican" are derided as unhealthy junk food. In fact, both were built on foundations of fresh, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But as people were removed from land and access to land, the they adapted foodways to reflect what was available and what White society valued - meat, dairy, refined flour, etc. Asian food in particular was adapted to suit White palates. We won't even get into the term "ethnic food" and how it implies that anything branded as such isn't "American" (e.g. White). Divorcing foodways from their originators is also hugely problematic. American food has a big cultural appropriation problem, especially when it comes to "Mexican" and "Asian" foods. As late as the mid-2000s, the USDA website had a recipe for "Oriental salad," although it has since disappeared. Instead, we get "Asian Mango Chicken Wraps," and the ingredients of mango, Napa cabbage, and peanut butter are apparently what make this dish "Asian," rather than any reflection of actual foodways from countries in Asia. Milk - The Perfect FoodCombining both nutrition research of the 19th century and also ideas about purity and sanitation, whole cow's milk was deemed by nutrition scientists and home economists to be "the perfect food" - as it contained proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all in one package. Despite issues with sanitation throughout the 19th century (milk wasn't regularly pasteurized until the 1920s), milk became a hallmark of nutrition advice throughout the Progressive Era - advice which continues to this day. Throughout the history of nutritional guidelines in the U.S., milk and dairy products have remained a mainstay. But the preponderance of advice about dairy completely ignores that wide swaths of the population are lactose intolerant, and/or did not historically consume dairy the way Europeans did. Indigenous Americans, and many people of African and Asian descent historically did not consume cow's milk and their bodies often do not process it well. This fact has been capitalized upon by both historic and modern racists, as milk as become a symbol of the alt-right. Even today, the USDA nutrition guidelines continue to recommend at least three servings of dairy per day, an amount that can cause long term health problems in communities that do not historically consume large amounts of dairy. Nutrition Guidelines HistoryBecause Anglo-centric foodways were considered uniquely "American" and also the most wholesome, this style of food persisted in government nutritional guidelines. Government-issued food recommendations and recipes began to be released during the First World War and continued during the Great Depression and World War II. These guidelines and advice generally reinforced the dominant White culture as the most desirable. Vitamins were first discovered as part of research into the causes of what would come to be understood as vitamin deficiencies. Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency), rickets (Vitamin D deficiency), beriberi (Vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency), and pellagra (Vitamin B2 or niacin deficiency) plagued people around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vitamin C was the first to be isolated in 1914. The rest followed in the 1930s and '40s. Vitamin fortification took off during World War II. The Basic 7 guidelines were first released during the war and were based on the recent vitamin research. But they also, consciously or not, reinforced white supremacy through food. Confident that they had solved the mystery of the invisible nutrients necessary for human health, American nutrition scientists turned toward reconfiguring them every which way possible. This is the history that gives us Wonder Bread and fortified breakfast cereals and milk. By divorcing vitamins from the foods in which they naturally occur (foods that were often expensive or scarce), nutrition scientists thought they could use equivalents to maintain a healthy diet. As long as people had access to vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, it didn't matter how they were delivered. Or so they thought. This policy of reducing foods to their nutrients and divorcing food from tradition, culture, and emotion dates back to the Progressive Era and continues to today, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Commodities & NutritionDivorcing food from culture is one government policy Indigenous people understand well. U.S. treaty violations and land grabs led to the reservation system, which forcibly removed Native people from their traditional homelands, divorcing them from their traditional foodways as well. Post-WWII, the government helped stabilize crop prices by purchasing commodity foods for use in a variety of programs operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the National School Lunch Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program. For most of these programs, the government purchases surplus agricultural commodities to help stabilize the market and keep prices from falling. It then distributes the foods to low-income groups as a form of food assistance. Commodity foods distributed through the FDPIR program were generally canned and highly processed - high in fat, salt, and sugar and low in nutrients. This forced reliance on commodity foods combined with generational trauma and poverty led to widespread health disparities among Indigenous groups, including diabetes and obesity. Which is why I was appalled to find this cookbook the other day. Commodity Cooking for Good Health, published by the USDA in 1995 (1995!) is a joke, but it illustrates how pervasive and long-lasting the false equivalency of vitamins and calories can be. The cookbook starts with an outline of the 1992 Food Pyramid, whose base rests on bread, pasta, cereal, and rice. It then goes to outline how many servings of each group Indigenous people should be eating, listing 2-3 servings a day for the dairy category, but then listing only nonfat dry milk, evaporated milk, and processed cheese as the dairy options. In the fruit group, it lists five different fruit juices as servings of fruit. It has a whole chapter on diabetes and weight loss as well as encouraging people to count calories. With the exception of a recipe for fry bread, one for chili, and one for Tohono O'odham corn bread, the remainder of the recipes are extremely European. Even the "Mesa Grande Baked Potatoes" are not, as one would assume from the title, a fun take on baked whole potatoes, but rather a mixture of dehydrated mashed potato flakes, dried onion soup mix, evaporated milk, and cheese. You can read the whole cookbook for yourself, but the fact of the matter is that the USDA is largely responsible for poor health on reservations, not only because it provides the unhealthy commodity foods, but also because it was founded in 1862, the height of the Indian Wars, during attempts by the federal government at genocide and successful land grabs. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the Department of the Interior was largely responsible for the reservation system, the land grant agricultural college system started by the Hatch Act was literally built on the sale of stolen land. In addition, the USDA has a long history of dispossessing Black farmers, an issue that continues to this day through the denial of farm loans. Thanks to redlining, people of color, especially Black people, often live in segregated school districts whose property taxes are inadequate to cover expenses. Many children who attend these schools are low-income, and rely on free or reduced lunch delivered through the National School Lunch Program, which has been used for decades to prop up commodity agriculture. Although school lunch nutrition efforts have improved in recent years, many hot lunches still rely on surplus commodities and provide inadequate nutrition. Issues That PersistEven today, the federal nutrition guidelines, administered by the USDA, emphasize "meat and three" style meals accompanied by dairy. And while the recipe section is diversifying, it is still all-too-often full of Americanized versions of "ethnic" dishes. Many of the dishes are still very meat- and dairy-centric, and short on fresh fruits and vegetables. Some recipes, like this one, seem straight out of 1956. The idea that traditional ingredients should be replaced with "healthy" variations, for instance always replacing white rice with brown rice or, more recently cauliflower rice, continues. Many nutritionists also push the Mediterranean Diet as the healthiest in the world, when in fact it is very similar to other traditional diets around the world where people have access to plenty of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, etc. Even the name - the "Mediterranean Diet," implies the diets of everyone living along the Mediterranean. So why does "Mediterranean" always mean Italian and Greek food, and never Persian, Egyptian, or Tunisian food? (Hint: the answer is racism). Old ideas about nutrition, including emphasis on low-fat foods, "meat and three" style recipes, replacement ingredients (usually poor cauliflower), and artificial sweeteners for diabetics, seem hard to shake for many people. Doctors receive very little training in nutrition and hospital food is horrific, as I saw when my father-in-law was hospitalized for several weeks in 2019. As a diabetic with problems swallowing, pancakes with sugar-free syrup, sugar-free gelatin and pudding, and not much else were their solution to his needs. The modern field of nutritionists is also overwhelmingly White, and racism persists, even towards trained nutritionists of color, much less communities of color struggling with health issues caused by generational trauma, food deserts, poverty, and overwork. Our modern food system has huge structural issues that continue to today. Why is the USDA, which is in charge of promoting agriculture at home and abroad, in charge of federal nutrition programs? Commodity food programs turn vulnerable people into handy props for industrial agriculture and the economy, rather than actually helping vulnerable people. Federal crop subsidies, insurance, and rules assigns way more value to commodity crops than fruits and vegetables. This government support also makes it easy and cheap for food processors to create ultra-processed, shelf-stable, calorie-dense foods for very little money - often for less than the crops cost to produce. This makes it far cheaper for people to eat ultra-processed foods than fresh fruits and vegetables. The federal government also gives money to agriculture promotion organizations that use federal funds to influence American consumers through advertising (remember the "Got Milk?" or "The Incredible, Edible Egg" marketing? That was your taxpayer dollars at work), regardless of whether or not the foods are actually good for Americans. Nutrition science as a field has a serious study replication problem, and an even more serious communications problem. Although scientists themselves usually do not make outrageous claims about their findings, the fact that food is such an essential part of everyday life, and the fact that so many Americans are unsure of what is "healthy" and what isn't, means that the media often capitalizes on new studies to make over-simplified announcements to drive viewership. Key TakeawaysNutrition science IS a science, and new discoveries are being made everyday. But the field as a whole needs to recognize and address the flawed scientific studies and methods of the past, including their racism - conscious or unconscious. Nutrition scientists are expanding their research into the many variables that challenge the research of the Progressive Era, including gut health, environmental factors, and even genetics. But human research is expensive, and test subjects rarely diverse. Nutrition science has a particularly bad study replication problem. If the government wants to get serious about nutrition, it needs to invest in new research with diverse subjects beyond the flawed one-size-fits-all rhetoric. The field of nutrition - including scientists, medical professionals, public health officials, and dieticians - need to get serious about addressing racism in the field. Both their own personal biases, as well as broader institutional and cultural ones. Anyone who is promoting "healthy" foods needs to think long and hard about who their audience is, how they're communicating, and what foods they're branding as "unhealthy" and why. We also need to address the systemic issues in our food system, including agriculture, food processing, subsidies, and more. In particular, the government agencies in charge of nutrition advice and food assistance need to think long and hard about the role of the federal government in promoting human health and what the priorities REALLY are - human health? or the economy? There is no "one size fits all" recommendation for human health. Ever. Especially not when it comes to food. Because nutrition guidelines have problems not just with racism, but also with ableism and economics. Not everyone can digest "healthy" foods, either due to medical issues or medication. Not everyone can get adequate exercise, due to physical, mental, or even economic issues. And I would argue that most Americans are not able to afford the quality and quantity of food they need to be "healthy" by government standards. And that's wrong. Like with human health, there are no easy solutions to these problems. But recognizing that there is a problem is the first step on the path to fixing them. Further ReadingMany of these were cited in the text of the article above, but they are organized here for clarity. I have organized them based on the topics listed above. (note: any books listed below are linked as part of the Amazon Affiliate program - any purchases made from those links will help support The Food Historian's free public articles like this one). EARLY NUTRITION SCIENCE

A HISTORY OF BODY MASS INDEX (BMI)

THE HISTORY OF THE CALORIE

MAKING "AMERICAN" FOOD

MILK - THE PERFECT FOOD

NUTRITION GUIDELINES HISTORY

COMMODITIES AND NUTRITION

ISSUES THAT PERSIST

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

1 Comment

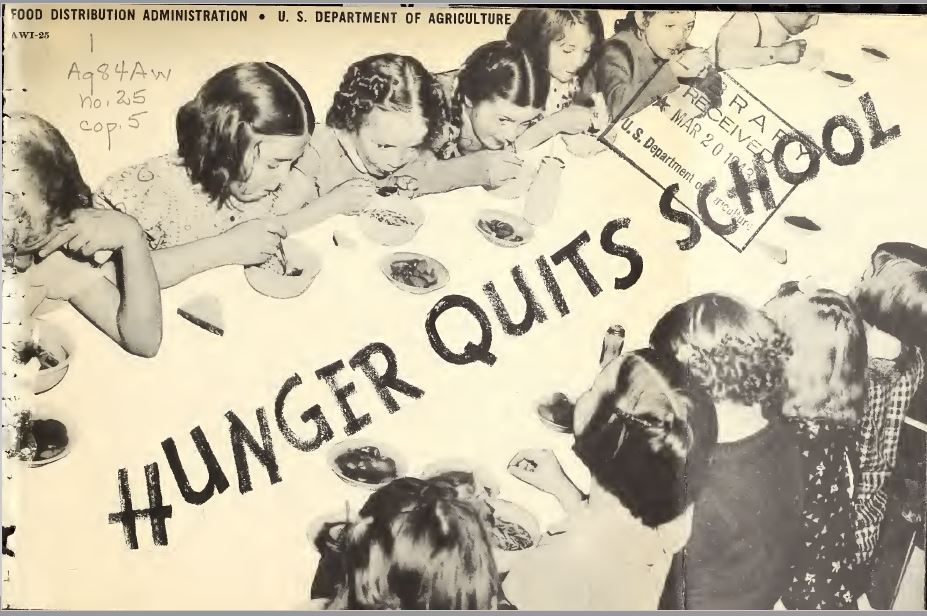

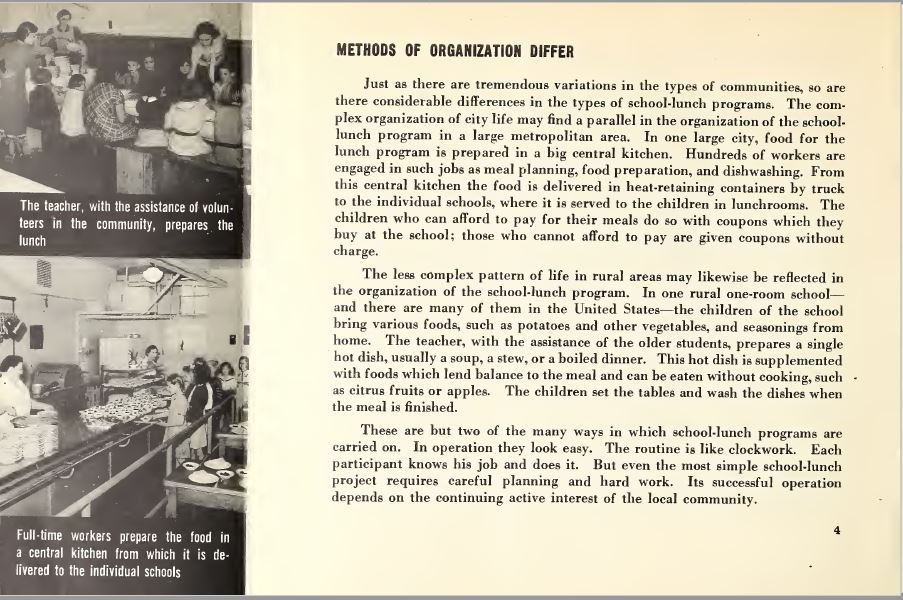

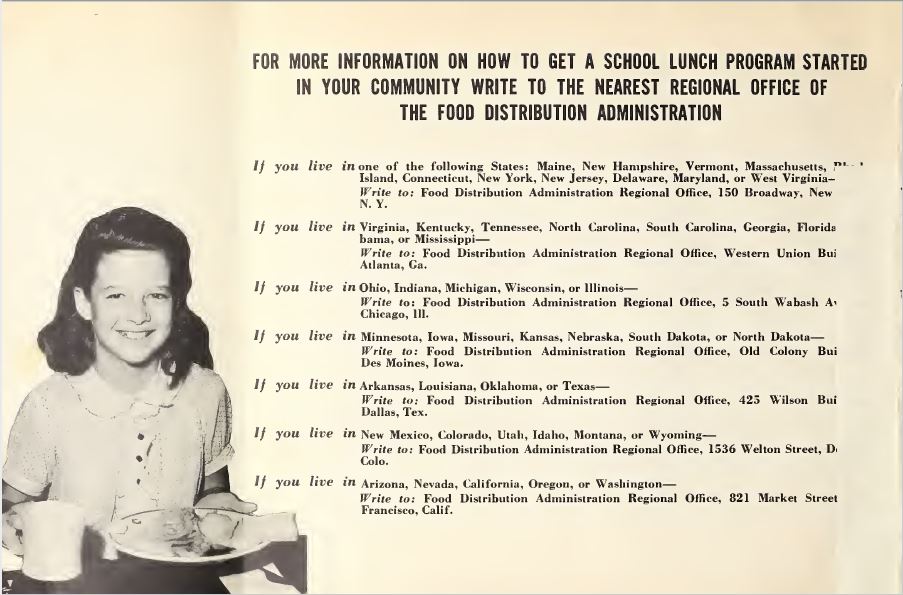

In 1943, the USDA published the informational booklet Hunger Quits School. On December 5, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the Food Distribution Administration, which oversaw, among other things, the school-lunch program. School lunch was influenced in part by the military draft. As many as a quarter of recruits were rejected for military service due to malnutrition. The panic around military readiness lead to many advancements in nutrition science and education of ordinary Americans about nutrition, including the development of the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations and yes, even school lunch. I've transcribed and shown the booklet in its entirety for your reading pleasure and edification. As you read you'll see how clearly school lunch programs were tied to military readiness even in the period, as well as how their execution differed in various communities. If you'd like to learn more about the history of school lunch, scroll to the bottom for reading recommendations. "Hunger has quit 93,000 schools throughout the United States where programs to provide noonday meals to students are operated by local communities in cooperation with the Food Distribution Administration. These programs are providing wholesome food to those who need it most - they are helping to build a healthy and physically fit population. Shortages of certain commodities cannot be permitted to impair the welfare of our future citizens. It is imperative that the youngsters who most need nourishing food get it in their school lunch. War adds to the urgency of the task. "A physically fit population and properly managed food supply are essential now more than ever before. Obviously, school-lunch programs are not substitutes for the courage of fighting men, for a fleet of airplanes, for guns, ships, tanks, or for the purchase of war bonds and stamps. Nevertheless, they are important in the Nation's War effort, since in modern total war the requirements for victory are indivisible." Images to left of text: Stylized black and white warship "Ships must transport food," stylized soldiers in a mess tent "Soldiers must eat," stylized workers in a factory with lunch room "Workers must eat," stylized woman typing and separate building with family in kitchen "Civilians must eat," stylized children sitting at table with knives and forks "Our children must eat." "WHY COMMUNITY SCHOOL-LUNCH PROGRAMS? "From the standpoint of the local community the reasons for operating lunch programs in the schools are immediate and easy to understand. Mothers and fathers, teachers and school administrators, doctors and health officers, and others in the community know the importance of having children eat properly. Since most children are away at school during lunch time for most of the year, the school lunch is an important part of the total diet of the individual. "Because parents, teachers, and others know the importance of proper food, that doesn't necessarily mean that all school children get the right kind of lunch or any lunch at all for that matter. In many cases, parents don't have enough money to put the right kinds of food in their children's lunch pails. In some cases - and this is increasingly true as more women go into war work - parents just don't have the time to put up the right kind of lunch for their children. In other cases, parents aren't well enough informed about nutrition to prepare an adequate lunch for their children. "All these and other factors have prompted local people to establish school-lunch programs as community enterprises. Programs are currently in operation to provide noonday meals to children in schools in every State and the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Thousands of persons - parents, teachers, volunteer workers, and well as paid workers - are giving their time and effort to carry on these projects, and millions of children are benefiting. "Although the Food Distribution Administration of the United States Department of Agriculture cooperated in school lunch programs in 93,000 schools during the 1941-42 school year by furnishing various foods without charge, the major responsibility for initiation of each program and for its successful operation is a community responsibility." Images to the right of text: Above, photo of young white boy outside a school eating a sandwich "The Cold Sandwich is no substitute." Below, photo of white children eating soup at a long table, caption continues ". . . For a Well-Balanced Hot Lunch." "METHODS OF ORGANIZATION DIFFER Just as there are tremendous variations in the types of communities, so are there considerable differences in the types of school-lunch programs. The complex organization of city life may find a parallel in the organization of the school lunch program in a large metropolitan area. In one large city, food for the lunch program is prepared in a big central kitchen. Hundreds of workers are engaged in such jobs as meal planning, food preparation, and dishwashing. From this central kitchen the food is delivered in heat-retaining containers by truck to the individual schools, where it is served to the children in lunchrooms. The children who can afford to pay for their meals do so with coupons which they buy at the school; those who cannot afford to pay are given coupons without charge. "The less complex pattern of life in rural areas may likewise be reflected in the organization of the school-lunch program. In one rural one-room school - and there are many of them in the United States - the children of the school bring various foods, such as potatoes and other vegetables, and seasonings from home. The teacher, with the assistance of the older students, prepares a single hot dish, usually a soup, a stew, or a boiled dinner. This hot dish is supplemented with foods which lend balance to the meal and can be eaten without cooking, such as citrus fruits or apples. The children set the tables and wash the dishes when the meal is finished. "These are but two of the many ways in which school-lunch programs are carried on. In operation they look easy. The routine is like clockwork. Each participant knows his job and does it. But even the most simple school-lunch project requires careful planning and hard work. Its successful operation depends on the continuing active interest of the local community." Images to left of text: Top, black and white photo of white adult women helping white students at lunch table, "The teacher, with the assistance of volunteers in the community, prepares the lunch." Bottom, black and white photo of open kitchen with white women cafeteria workers and line of white children, "Full-time workers prepare the food in a central kitchen from which it is delivered to the individual schools." "HOW TO GET STARTED IN YOUR COMMUNITY "Suppose the school in your community does not have a lunch program and you would like to see one in operation. How do you go about getting it started? "The first thing to keep in mind is that this is a job for your local people - yourself and your neighbors. Various agencies of the Government may lend you technical assistance, but the primary responsibility is yours. "If you have the interest and the willingness and the perseverance to follow through on a community lunch program, the thing to do is to get together with your neighbors, the parents of other school children, and see how much interest you can arouse and how much support you can get for the proposal. You will need much support if your plan is to be a success. "What you do next depends on what kind of community you live in. The procedure in a city of 100,000 population is different from that in a rural area. The steps to take are different in a city of 20,000 from those in a village of 2,000. But the procedure that has been followed in these different types of communities will give you an idea of what lies ahead in your effort to get started. "In one city of more than 100,000 population a group of mothers presented their proposal for a school-lunch program to the teachers and the principal of their neighborhood school. They were given a sympathetic hearing and arrangements were made to present the plan to the city superintendent of schools and the board of education. The meetings resulted in a survey to ascertain what facilities were available in the various schools for the operation of a lunch program on a city-wide basis, what additional facilities would have to be provided, and what would be needed in the way of financing. "The survey completed, plans were laid to put the school-lunch program into operation. Some of the needed facilities were provided from public funds, and" [. . . continued on next page] Image to right of text: Black and white photo of seated white adults as at a public meeting, "This is a job for local people . . . yourself and your neighbors." [continued from previous page] "the remainder was purchased by a number of civic and fraternal organizations which took an interest in the project. A permanent staff of paid workers was hired, and their work was supplemented by the work of volunteers. Much of the food was purchased locally, but some was provided without cost by the Food Distribution Administration. Those children who could pay a nominal sum for their lunch did so, and those who could not afford to pay were fed without charge. "Teachers took the initiative in serving lunches at school in one village of 2,000. They had seen some children sitting out in the cold eating sandwiches and others having nothing at all to eat. Investigating the possibilities of doing something about it, they learned that a school-lunch project was in operation in a nearby community. At the next meeting of the parent-teacher association they brought up the idea of a school-lunch program. The result was the appointment of a committee to visit the neighboring village and see how the program operated there. The committee made an enthusiastic report at the next meeting, and it was decided to present the whole matter to the local school board. "After a number of conferences with representatives of the State welfare department, the FDA, and other interested groups, the school board agreed to formally sponsor the lunch program. A lunchroom was set up in part of the school basement which was not in use. The county home demonstration agent provided technical assistance in meal planning. Two full-time paid workers were hired, and the rest of the labor forced was made up of volunteers. "The entire community, in one rural area, pooled its efforts to get a lunch program going in its one-room school. It was a real job, as the school lacked" [. . . continued on next page]. Images to left of text: Top photo, white adults gather around a table looking at papers "Parents and school authorities discuss a proposed school-lunch program." Bottom photo, white adults sit in auditorium, "Civic and fraternal organizations play an important part in the success of many school-lunch programs." [continued from previous page] "everything in the way of facilities and had no available space for cooking or serving. The men of the community solved the problem by getting together enough salvaged lumber and building a lean-to addition to the school, also tables and benches. The women of the community meanwhile organized a shower to collect the necessary pots, pans, and other cooking utensils. A merchant in the nearby town donated a second-hand stove. Each child brought his dishes and "silver" from home. Each family provided foods, and the mothers took turns going to the school to do the cooking. The school board, of course, approved the undertaking and formally sponsored the program to make it eligible for FDA assistance. "Should you contact anyone else for help in getting a school-lunch program going in your community? There is no one answer. In many counties there are home-demonstration agents, home-economics teachers, and home supervisors of the Farm Security Administration who can supply technical advice and assistance. Parent-teacher organizations, civic organizations, chambers of commerce, veterans' organizations and auxiliaries, State and local education departments, State and local health organizations, State and local welfare agencies, and the WPA are among the groups which have helped in other communities. In many cities there are representatives of the Food Distribution Administration who can supply information and advice regarding procedure for obtaining reimbursement from the FDA for the purchase of specified foods. "Your first objective in getting a school lunch program started is, of course, better meals for the children in school. This, too, was the main objective in the thousands of communities which are now operating the programs. These communities have found that many benefits to the children in school have stemmed from better nutrition." Images to right of text: top photo, white women stand next to table of plates of food, actively plating, "Teachers took the initiative in serving school lunches in a small community. Bottom photo, two white women stand in kitchen cooking, "Lunches like this mean more adequate diets for millions of children every day." "BETTER NUTRITION NOT THE ONLY BENEFIT "Records kept in many schools show that attendance is better after a school-lunch program is put in operation than it was before. One school reports 11 percent fewer absent than before the lunch program was started, another 8 percent; and still another 15 percent. Investigation shows that in many cases the better attendance is the result of less illness. Proper food does much to prevent illness, especially in growing children. "Thousands of doctors and dentists have gone into the armed forces. War needs have taxed our health facilities all along the line. It is more important than ever that as much illness as possible be prevented. To the extent that school lunches keep children healthy they are making a direct contribution to the welfare of the Nation at war. "There are many striking reports of children who have been built up physically as a result of eating school lunches. In one midwestern community an undernourished boy gained 25 pounds during a single school year. Many examples like this could be cited. Not only such run-down children, but in many cases the entire class of a school reports better physical fitness as a result of school lunches. "Many prominent health authorities have pointed out that it is a waste of the taxpayers' money to try properly to educate children who are malnourished. They simply cannot do good work when they are hungry. Such records as have been kept show that in almost every school where adequate lunches are provided the students are making better progress in their studies than formerly. "Teachers report that students are better behaved when they are properly nourished. Eating together in groups improves the table manners and the per-" [. . . continued on next page] Images to left of text: Top photo of white men administering vaccinations to other white men, "Thousands of doctors and dentists have gone into the armed forces." Bottom, young white children play on equipment outside, "Keeping children healthy is a direct contribution to the welfare of the Nation at war." [continued from previous page] "[per]sonal habits of many youngsters. Through the example of watching their schoolmates eat certain foods, children come to like foods previously unfamiliar. They eat what is put on the table. "In many communities the benefits of the lunch program are carried into the home. Children have reported back to their mothers the things that they learn about diet and better nutrition, with the result that the meals of whole families frequently have improved. "It is apparent that these benefits to children are all good reasons for parents, teachers, and local communities to be interested in school-lunch programs. How about the Federal Government and the Food Distribution Administration? "FDA'S PART IN SCHOOL-LUNCH PROGRAMS "One of the important jobs of the FDA is to assist in the management of the Nation's wartime food supply through the stimulation of increased production, the maintenance of machinery for orderly marketing, and the prevention of waste. School lunches, in addition to feeding those who most need proper nourishment, are one of the devices used in helping to do these jobs. "In recent months the war effort has made it necessary not only to maintain existing levels of food production but to increase these levels greatly. Although there has been a tremendous expansion in food production during the past year, some production goals have been revised upward. Under these conditions, when concerted efforts are being made to increase food production, it is important that farmers be able to market all they grow. Market stability is thus an important factor in stimulating increased production. "Not only is market stability important as an incentive to ever increasing output, but it is important in guarding against waste of food already produced." Images to right of text: top, a white farmer stands in the furrows of a field with sacks of potatoes, "It is important that good use be made of all that farmers produce." Bottom, two white men shake hands outdoors, "Sponsors buy from local producers and are reimbursed by the Food Distribution Administration." "In the past unstable markets sometimes made it impossible for farmers to harvest their entire crop and sell it at a price that would cover their costs. The result, when such conditions prevailed, was that part of the crop was not harvested but was left in the fields or in the orchards to rot. Such conditions might arise again for some commodities, even though supplies of certain other foods may be short, and if they do the school-lunch programs are a mechanism to prevent possible waste. "Sometimes food purchased originally for shipment abroad under the lend-lease program could not be used for this purpose because of changed requirements of our allies, lack of shipping space, or other uncontrollable factors. In such cases the school-lunch program provided a desirable outlet for the commodities. "In the past, the FDA's job in connection with school-lunch programs was to buy up foods and to channel them to schools for use by the youngsters who needed them most. Purchases were sent in carlots to the welfare departments of the various States. The State welfare department distributed foods to county warehouses which in turn distributed part of the supply for use in lunch programs in eligible schools. "Shortages born of the war - transportation, equipment, manpower - necessitated a revision of this distribution plan. In some large communities, commodities are still distributed to schools from warehouses operated by State welfare departments, but in most communities the program is now carried on under a local purchase plan. "Under this new local purchase plan, the FDA reimburses the sponsors for the purchase price of specified commodities for the lunches. The commodities eligible for purchase under the plan are given in a School Lunch Foods List which is issued from time to time. Products in regional abundance and those high in nutritional value have first consideration in compiling the lists. Sponsors buy from producers or associations of producers, or from wholesalers or retailers. They are reimbursed for the cost of the commodities up to a specified amount" [. . . continued on next page]. Images to left of text: top, two men load stack barrels, "A few foods are still available from the FDA for delivery to schools in some areas." Bottom, box trucks lined up outside a building as a man loads a box, "Sponsors arrange for the delivery of foods to the schools where they are used." [continued from previous page . . .] "which is based on the number of children participating, the type of lunch served, the financial resources of the sponsor, and the cost of food in the locality. "In addition to those foods for which the FDA provides reimbursement of the purchase price, local sponsors buy with their own funds such additional commodities as are needed to round out the meals. What better use can be made of some of our food supplies than to make them available to growing children who otherwise may not get enough to eat? "WHAT SCHOOLS ARE ELIGIBLE? "Schools eligible to participate in the program must be of a nonprofit-making character and must serve lunches to children who need them. Schools receiving FDA assistance must permit no discrimination between children who pay for their lunches and those unable to pay. A formal sponsor, representing the school, must enter into an agreement with the FDA that the conditions governing the program will be complied with. Nonprofit-making nursery schools and child-care centers are eligible for participation in the program. "From the standpoint of our national welfare it is important that all school children be properly nourished, and that all food produced be properly utilized. This explains the interest of the Federal Government in the community school-lunch program, since the Government represents all the people acting in concert. "Although the school-lunch programs alone have not succeeded in reaching all children who need more adequate nourishment, they have been instrumental in bringing food to a substantial number of them. During the peak month of March 1942 the lunch programs in which the FDA was cooperating fed 6,000,000 children. Nor have the lunch programs alone succeeded in making possible the most effective utilization of all foods produced. But they have been one means of working toward these two objectives. "The lunch programs have been a means of forcing hunger out of a great many schools in the United States." Images to right of text: Top: young white girls at play on a see-saw. Middle: a school building. Bottom: a white nun gives a sandwich and bottle of milk to a young white boy. "FOR MORE INFORMATION ON HOW TO GET A SCHOOL LUNCH PROGRAM STARTED IN YOUR COMMUNITY WRITE TO THE NEAREST REGIONAL OFFICE OF THE FOOD DISTRIBUTION ADMINISTRATION "If you live in one of the following States: Main, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, or West Virginia - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 150 Broadway, New York, N.Y. "If you live in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, or Mississippi - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, Western Union Building, Atlanta, Ga. "If you live in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, or Illinois - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 5 South Wabash Ave., Chicago, Ill. "If you live in Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, or North Dakota - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, Old Colony Building, Des Moines, Iowa. "If you live in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, or Texas - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 425 Wilson Building, Dallas, Tex. "If you live in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Montana, or Wyoming - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 1536 Welton Street, Denver, Colo. "If you live in Arizona, Nevada, California, Oregon, or Washington - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 821 Market Street, San Francisco, Calif." And that is the end of the transcription! What did you think? Were there any surprises in there for you? I had known for a long time that the school lunch program was a way to use up agricultural surpluses AFTER the war, but hadn't realized that using up wartime surpluses was a factor since the beginning. I also liked the emphasis on treating children who couldn't afford to pay no differently than those who could. FURTHER READING: If you'd like to learn more about the history of school lunch, check out these additional resources. (Purchases made from Amazon links help support The Food Historian):

Happy reading! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed