|

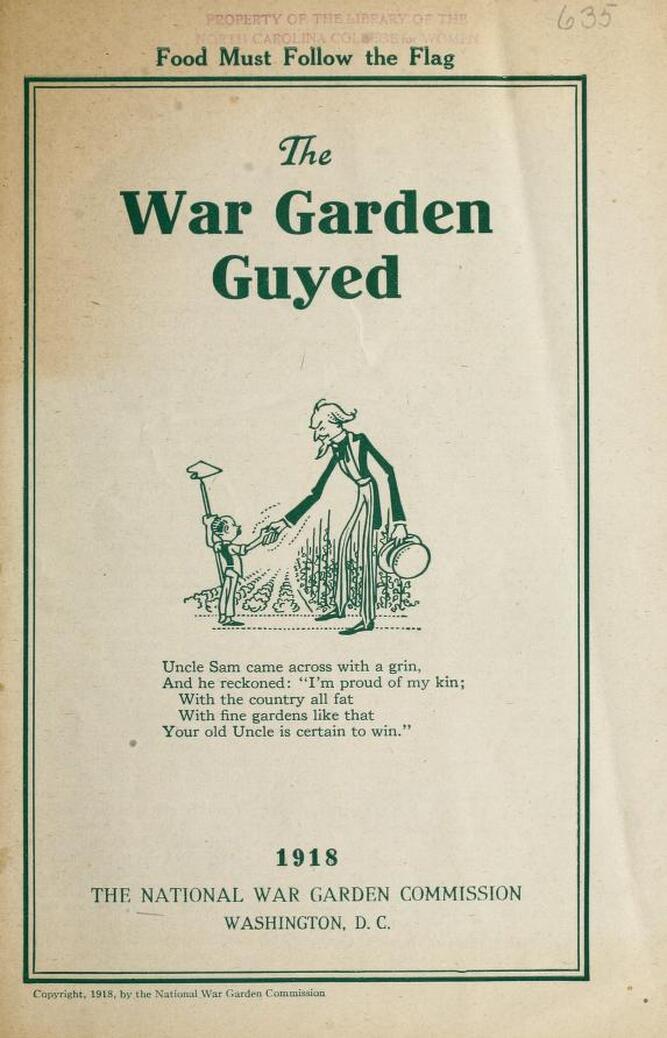

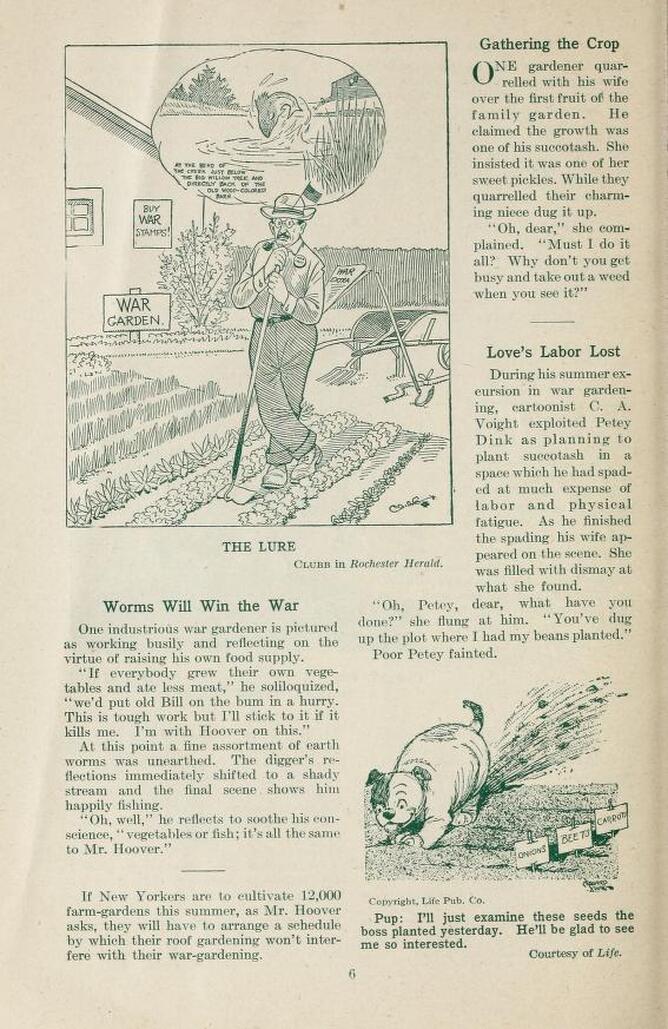

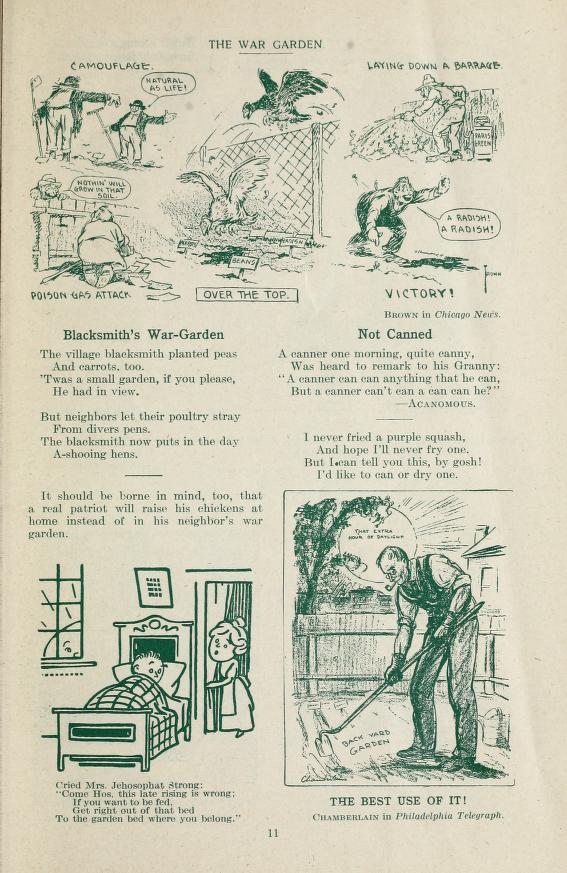

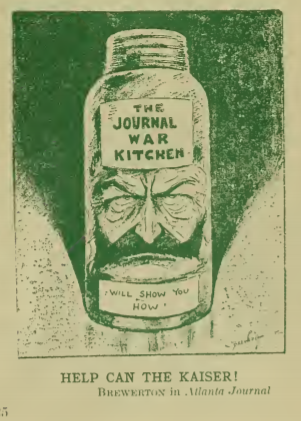

Although literal tons of snow have fallen across the United States in the past week or so, it's still beginning to feel like spring, which for many of us means our thoughts turn to gardening. If you know anything about World War II, you've probably heard of Victory Gardens. But did you know they got their start in the First World War? And the popularity of "war gardens" as they were initially called, is largely thanks to a man named Charles Lathrop Pack. Pack was the heir to a forestry and lumber fortune, and pumped lots of his own money into creating the National War Garden Commission, which promoted war gardening across the country, along with food preservation. They published a number of propaganda posters and instructional pamphlets. Today's World War Wednesday feature is another pamphlet, but its primary audience was not the general public, but rather newspaper and magazine publishers! Full of snippets of poetry, jokes, cartoons, and articles published by newspapers and magazines around the country, even the title was a bit of a joke. "The War Garden Guyed" is a play on the words "guide" and the verb "guy" which means to make fun of, or ridicule. So "The War Garden Guyed" is both a manual to war gardens and also a way to make fun of them. In the introduction, the National War Garden Commission (likely Charles Lathrop Pack himself), writes: "This publication treats of the lighter side of the war garden movement and the canning and drying campaign. Fortunately a national sense of humor makes it possible for the cartoonist and the humorist to weave their gentle laughter into the fabric of food emergency. That they have winged their shafts at the war gardener and the home canner serves only to emphasize the vital value of these activities." Each page of the "guyed" has at least one image and a few bits of either prose or poetry. The below page is one of my favorites. In the upper cartoon, an older man leans on his hoe in a very orderly war garden. His house in the background features a large "War Garden" sign and a poster saying "Buy War Stamps!" In his pocket is a folded newspaper with the headline "War Extra." But he is dreaming of a lake with jumping fish and the caption - indicating the location of the best fishing spot. The cartoon is called "The Lure" and demonstrates how people ordinarily would have been spending their summers. In the lower right hand corner, a roly poly little dog digs frantically in fresh soil. Little signs read "Onions, Beets, Carrots." The caption says "Pup: I'll just examine these seeds the boss planted yesterday. He'll be glad to see me so interested." Another article on the page is titled "Love's Labor Lost." It reads: "During his summer excursion in war gardening, cartoonist C. A. Voight exploited Petey Dink as planning to plant succotash in a space which had had spaded at much expense of labor and physical fatigue. As he finished the spading his wife appeared on the scene. She was filled with dismay at what she found. 'Oh Petey, dear, what have you done?' she flung at him. 'You've dug up the plot where I had my beans planted.' Poor Petey fainted." Many of the bits of doggerel and cartoons poked fun at inexperienced gardeners like Petey Dink. Pests, animals, digging up backyards and hauling water, the difficulty in telling weeds from seedlings, and finally the joy at the first crop. This page has a comic at the top that illustrates these trials and tribulations perfectly, through the lens of war. In the upper left hand corner, a sketch entitled "Camouflage" depicts a man who has just finished putting up a scarecrow who crows, "Natural as life!" as he poses exactly the same as his creation. Below, another called "Poison Gas Attack" depicts a neighbor leaning over the fence to comment "Nothin will grow in that soil" at a man kneeling in the dirt, a bowl of seed packets and a hoe on either side of him. The title implies that the neighbor is full of hot air and poison. The center scene, titled "Over the Top," shows a pair of chickens gleefully flying over a fence to attack a plot marked "Carrots," "Beans," and "Radishes." In the top right-hand corner, in a sketch titled "Laying Down a Barrage," a man with a pump cannister labeled "Paris Green" is spraying his plants. Paris Green was an arsenical pesticide. And finally, in one labeled "Victory!" a man gleefully points to a small seedling in an otherwise empty row and cries, "A radish! A radish!" In a bit of verse called "Not Canned" reads: A canner one morning, quite canny, Was heard to remark to his Granny: "A canner can can anything that he can, But a canner can't can a can can he?" And finally, apt for this past weekend's Daylight Savings Time "spring forward" is an evocative sketch depicts a man hoeing up his back yard garden while a large sun shines brightly and reads "That extra hour of daylight." The sketch is captioned, "The best use of it!" "The War Garden Guyed" has 32 pages of verse, doggerel, short articles, and cartoons. Charles Lathrop Pack was correct when he said the newspapers evoked "gentle laughter" as none of the satirical sheets actually discourage gardening. Indeed, most of the text is directly in line with the propaganda of the day promoting the development of household war gardens and the movement to "put up" produce through home canning and drying. Many of the cartoons directly connect to the war itself, comparing fighting pests to fighting Huns, pesticides to ammunition and "trench gas," and equating canning and food preservation efforts with vanquishing generals. What the booklet does do is poke fun at all of the hardships and difficulties first-time or inexperience gardeners would face. Stray chickens, cabbage worms and potato beetles, dogs and children, competing spouses, naysaying neighbors, post-vacation forests of weeds, and trying desperately to impress coworkers and neighbors with first efforts. War gardens were no easy task, and there were plenty of people who felt that they were a waste of good seed. But Pack and the National War Garden Commission persisted. They believed that inspiring ordinary people to participate in gardening would not only increase the food supply, but also free up railroads for transporting war materiel instead of extra food, get white collar workers some exercise and sunshine, and provide fresh foods in a time of war emergency. How successful the gardens of first-year gardeners were is certainly debatable. But in many ways, war gardens were more about participating than food. After the war, Pack rebranded his "war gardens" as "victory gardens," asking people to continue planting them even in 1919. The idea struck such a chord that when the Second World War rolled around two decades after the first had ended, "victory gardens" and home canning again became a clarion call for ordinary people to participate in the war on the home front. The full "War Garden Guyed" has been digitized and is available online at archive.org. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

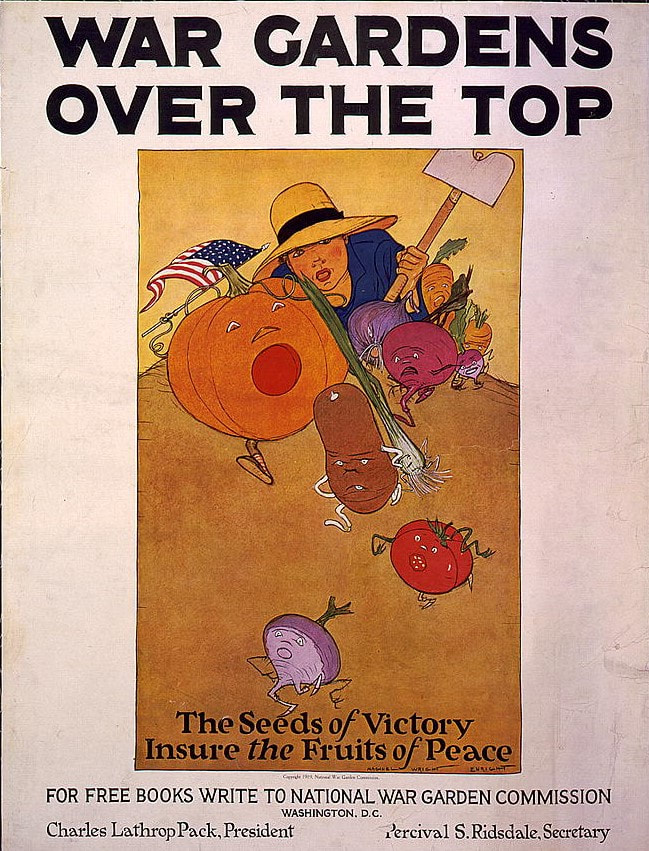

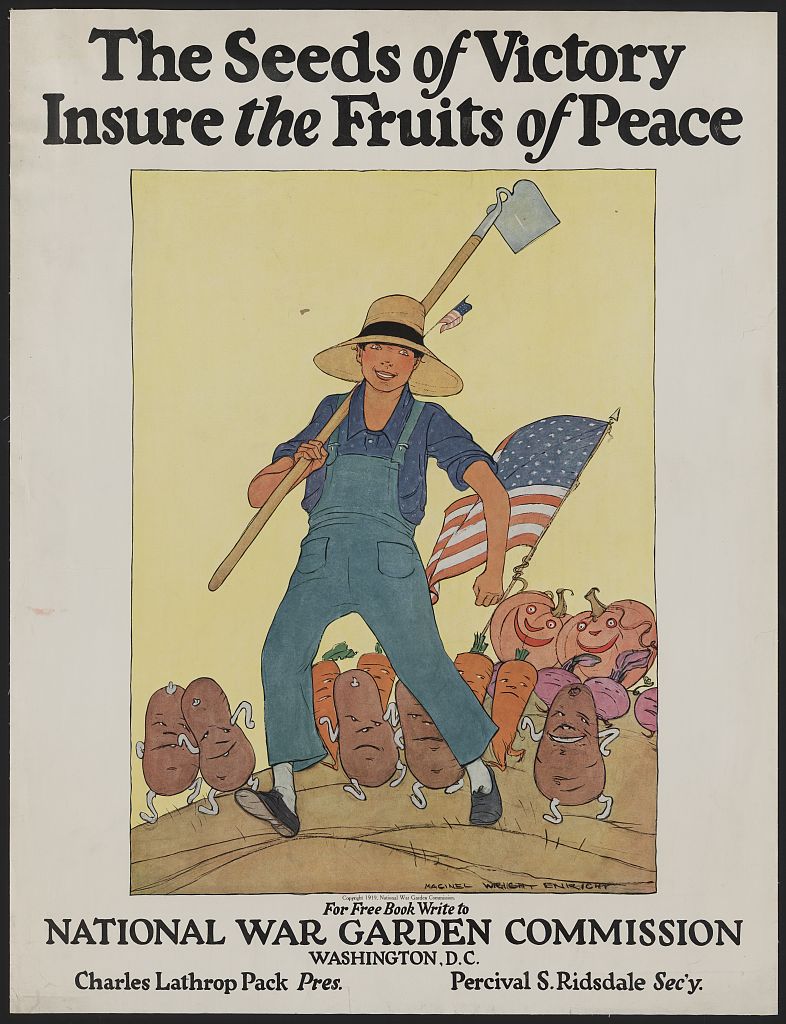

This is one of the more famous food-related posters of the First World War. Created by famous illustrator and artist James Montgomery Flagg, "Sow the Seeds of Victory," and its sister poster (below) "Will you have a part in Victory?" were both produced by the National War Garden Commission, headed by Charles Lathrop Pack. The bottom of each poster reads "Every Garden a Munition Plant" with instructions in the lower right-hand corners reading "Write to the National War Garden Commission - Washington, D.C. for free books on gardening, canning, & drying." The posters both feature the same image - the United States embodied as Columbia, striding boldly, sandaled feet marching through a freshly plowed field, and broadcasting seed from a round basket. Columbia wears her Classical-style dress in the colors of the American flag - red, white, and blue - and wears a Phyrgian cap on her head, a symbol of freedom and liberty. The poster implies that by planting gardens, ordinary Americans could "Sow the seeds of Victory" and "plant and raise your own vegetables" - helping the war effort both literally and symbolically. Although "Every Garden a Munitions Plant" is a bit on the nose, the martial language helped reinforce the importance of growing vegetables at home, rather than consuming fuel and war materiel by purchasing vegetables grown far away, or canned commercially. The phrasing of the first poster is more in line with the sentiment of the image, and was likely the first produced. "Will you have a part in Victory" implies that the viewers may have already seen the first poster and understand its original intent. The Library of Congress estimates that these posters were produced in 1918, which is entirely possible, but the National War Garden Commission had instructional booklets on gardening, canning, and drying all published in 1917. Given that the NWGC was one of the first organizations to advocate for war gardens, even before the outbreak of war, so it is possible these are from 1917. Ironically, James Montgomery Flagg helped hasten the demise of Columbia as a symbol of the United States. His depiction of Uncle Sam, first featured on the July 6, 1916 cover of Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper asking "What are YOU doing for Preparedness?" - he later repurposed the image, inspired by Britain's Lord Kitchener, into the infamous "I Want YOU" Army recruitment poster, which was so effective it was recycled for the Second World War. By the 1930s, Uncle Sam (and his feminine counterpart, Aunt Sammy) had completely superseded Columbia as a symbol of the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! The National War Garden Commission, a private organization funded by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, was one of the most prolific sources of wartime propaganda posters outside the federal government. One of the major proponents of civilian garden programs, even before the U.S. entered the First World War, the National War Garden Commission gave away free booklets on gardening, canning, and food preservation. The above poster features a boy with a spade and straw hat climbing over a mound of dirt. In the lead are series of anthropomorphic vegetables, including a pumpkin carrying the American flag, and all appear to be yelling or screaming as they run down the hill. Reading "War Gardens Over the Top," and "The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace," the poster brings to mind the "boys" going "over the top" of the trenches in battle. This use of military language in propaganda posters was not uncommon, but this particular phrase likely did not have the full impact in the period that it does now. Today, we realize how horrific the charges of men "over the top" and across no-man's land between the trenches on the front really were. But in the period, it's likely people had only sanitized newspaper articles and perhaps a propagandized newsreel or two to give them a frame of reference for the term. In this second poster, which also reads "The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace," our military allusions are a little more innocent. Here our same overall-ed and straw-hatted boy marches in a parade, hoe over his shoulder, accompanied by more anthropomorphized vegetables. These vegetables look less than thrilled to be marching, but the sentiment is the same. Both posters were published in 1919, technically AFTER the war was over. But as with most wars, the end of conflict does not mean that everything goes back to normal. There were numerous attempts by a number of organizations, including the federal government, to get Americans to continue to conform to wartime measures, including voluntary rationing and war gardens, which were termed victory gardens after the cessation of hostilities, well in to 1919 and even 1920. Here, the National War Garden Commission makes the argument that the "seeds of victory insure the fruits of peace," meaning that by continuing to plant vegetable gardens and free up domestic food supply for shipment overseas, Americans could help stabilize and rebuild Europe in the wake of the war. Illustrated by Maginel Wright Enright, primarily known as a children's book illustrator, the posters have a luminous clarity, even if Enright was not particularly good at giving vegetables convincing facial expressions. Lots of folks are starting year two of pandemic gardens - are you one of them? I am! Raised beds are going in this year and I already have my seeds and a plan. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

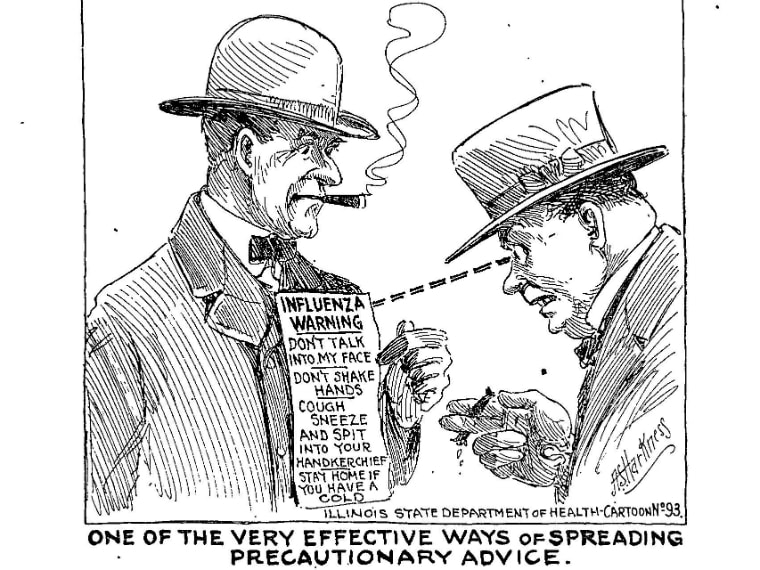

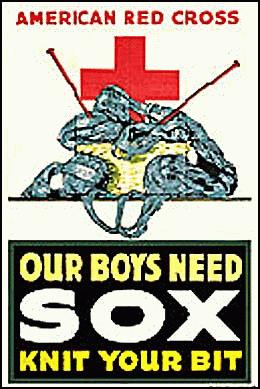

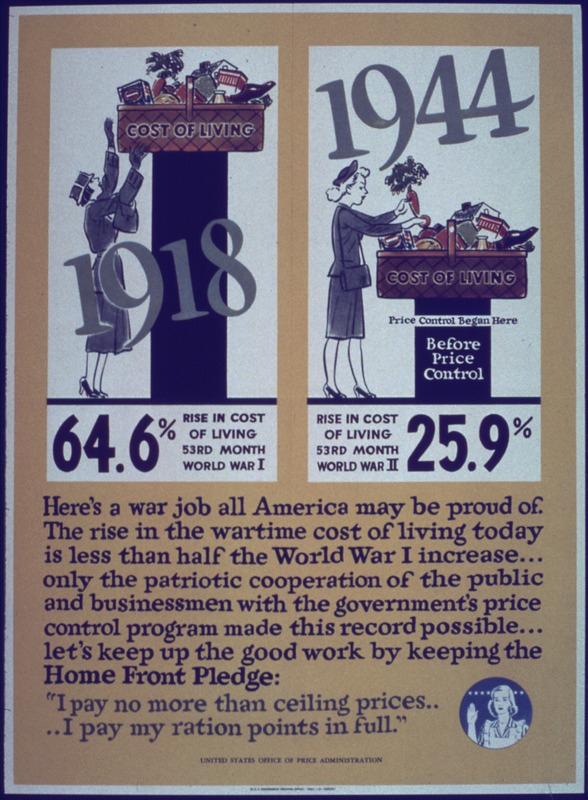

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. Y'know that old saw, "Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it?" Well, like a lot of old adages, this one has a big grain of truth in it. Historians often can see parallels to the modern world as they study history. Indeed, my area of specialty - the Progressive Era and World War I home front - has led to LOTS of comparisons to modern life. But with the addition of the coronavirus lockdown, the comparisons grew more numerous. To that end, I thought I would catalog some of the striking similarities. Failure of Bureaucracy: Military SupplyOne thing that has becomes especially striking at this time is the failure of the federal government to manage national supplies during an emergency. In this instance, it's the management of medical supplies for COVID-19, particularly personal protective equipment (a.k.a. PPE). States are competing on an open market and with each other, driving up prices and leading to shortages. To make up the shortfall, ordinary citizens are creating homemade versions of masks, face shields, and other equipment. During the first months of the U.S. entrance into World War I, the exact same thing was happening. Historian Robert Ziegler in his book America's Great War: World War I and the American Experience, outlines the deplorable state of military supply following the Spanish American War. Individual battalions were competing with each other on the open market to purchase supplies, thus driving prices up. In addition, the United States had never fielded such an enormous army and the production of other military supplies, such as uniforms and rifles had yet to keep up with the demand of a suddenly-enormous army. According to historian David M. Kennedy, in his book Over Here: The First World War and American Society, soldiers were sent to Europe with hardly any training. Men and boys who had been recruited in July, 1918 were on the front lines by September. Some men arrived never having used a rifle, and had to take an intensive 10 day course before being sent into battle. The logistics of shipping war materiel, both within the borders of the United States and overseas was also a mess, causing railroad and port backups. Some credit the poor supply of soldiers in training camps (inadequate clothing, bedding, housing) with exacerbating the effects of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Combined with this was the efforts of the American Red Cross. Famed for providing bandages and nursing aid during the American Civil War, thousands of chapters sprang up across the nation and throughout 1917, women were encouraged to "knit their bit" by knitting sweaters, socks, wristers, and watch caps for "our boys" being sent overseas. Why? Likely because military supply chains were, as stated, in shambles and because it was easier (and cheaper) to task the nation's women with keeping soldiers warm than to mobilize factories. Wool socks in particular were in high demand because of the poor conditions in the trenches. But by 1918, according to historian Christopher Cappazola in his book, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, the federal government was frantically telling women to STOP knitting, likely because military supply was completely reorganized. Although there are plenty of resources about knitting in WWI and the American Red Cross (including this lovely one), few people seem to have made the connection between "knitting your bit" and the failure of military supply. It was only part-way through American participation in the war that the federal government reorganized military supply under a centralized Quartermaster General. It wasn't until the Korean War that the United States passed the Defense Production Act (1950), which empowered the federal government to compel private business to prioritize the production of war materiel and prevent hoarding and price gouging. If the United States were to learn the lesson of WWI supply today - the federal government would coordinate with individual states to purchase - and allocate - medical supplies where most needed, instead of bidding against states on the open market. Xenophobia, Immigration, RaceIn the years leading up to the First World War, the United States was inundated with immigrants from all over the world, but particularly Eastern and Southern Europe. The United States was also recovering from the abandonment of Reconstruction and Black Americans were becoming more and more prosperous, with a growing middle class. Combined with a brain and labor drain on rural areas, this led to people like President Theodore Roosevelt warning of "race suicide" for White Anglo Americans unable to keep pace with the more fertile immigrants. Roosevelt also worried about rural life and started the Country Life Commission to study and combat the drain of population from rural America to urban areas. Tempted by "cosmopolitan" life, reformers worried, young people would be corrupted and the bedrock foundation of democracy - the landowning yeoman farmer - would diminish. Unfortunately for reformers, the majority of people in rural areas lived difficult lives and particularly in the South, most did not own the land they farmed. But the idea that rural America, and farmers in particular, are the "salt of the earth" is an idea that has persisted even today. With "flyover country" being courted by politicians, especially conservative ones, with every election. Immigration and race remain hallmark dogwhistles in modern politics. The Trump campaign used the slogan "America First" on the campaign trail - echoing the campaign slogan of Woodrow Wilson leading up to his first term as a neutral isolationist. It was a policy he would abandon in his second term, as the U.S. entered World War I in the spring of 1917. Americans were notoriously isolationist in the early 20th century (except for their colonialist ambitions in Central America, Hawaii, and the Phillipines) and America's first propaganda machine had to be created to convince them that joining the war was a good idea. To convince them, Woodrow Wilson invented the idea of defending and spreading democracy (and American exceptionalism) abroad - a policy that has continued to be used in every American war since then. Attempts to Americanize immigrants remained in effect throughout the war. Progressive reformers from settlement houses and canning kitchens on up to proponents for the war which thought a draft would help Americanize immigrants tried to force people into the mold of White Anglo American (usually Northeastern) culture. Black Americans faced similar pressures, and segregated versions of just about every middle-class voluntary organization - including the Red Cross - was implemented during the war. Following the war, newly economically mobile Black Americans, buoyed by industrial jobs for war production, faced even more hostility than before. Resentment by racists clashed with confident (and armed) veterans returning from war. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is just one example of Black WWI veterans attempting to defend themselves and their communities. Race riots, lynchings, and a dramatic expansion of the Ku Klux Klan were the hallmarks of 1919, 1920, and beyond. Today, Black American communities still deal with over-policing, incarceration, and violence. Latinx-Americans have dealt with a dramatic ramp-up of incarceration, family separation, and deportation (even of children), as well as more casual racism. And Asian-Americans in particular have borne the brunt of some horrific incidents of racism directly related to the coronavirus - as the ignorant believe that they (regardless of whether or not they had been to China recently, or were even of Chinese descent) were "carriers" of the disease - another old saw of racism most famously used by Nazis against the Jews (among others). The High Cost of LivingIn the two decades leading up to WWI, the United States underwent a series of depressions and recessions. Starting with the Depression of 1893 (which the US did not recover from until 1897-98), and with smaller recessions in 1907 and 1913-14, the "high cost of living" (commonly abbreviated as "HCL" or "H.C.L.") saw a dramatic rise in cost of living, including food and housing, while wages stagnated. Called "stagflation" by economists, this situation led to labor unrest, and strikes, food boycotts, and food riots were all common during this time period. Socialists were also in political ascendancy due to income and labor inequalities. Labor strikes were often broken by deadly force. Food boycotts and riots remained the purview of the desperate - often women with starving children which tugged at the heartstrings of wealthy and middle-class White Progressives, even as some were organized by socialist activists (read about the 1917 food riots in New York City). Many of the strikes and riots of the 1900s and 1910s led to serious labor reform, including the ending of child labor, worker safety reforms, reduced hours, and more. New York City during WWI tried to pass a minimum wage law, but it was vetoed by the Mayor. Today's parallels include a different sort of high cost of living - most "luxury" items are cheaper than they've ever been, but housing, education, healthcare, and food costs have risen by as much as 200% in the last 20 years. In addition, democratic socialists and real, "bread and roses" socialists have seen their numbers spike in the last few years. Activists are fighting for a minimum wage increase, universal healthcare, and other reforms, although union membership has taken a steep dive in the last few decades. Coronavirus has only highlighted the "essential" role many low-wage workers play in American life, and some retail workers, cleaners/janitors, and restaurant workers are now being hailed as heroes alongside medical professionals and scientists. War Gardens & RationingOne particularly fascinating trend that appears to be occurring right now is the skyrocketing sale of vegetable seeds and plants. Tied in part to the fact that so many Americans are sheltering in place and have time to garden, the resurgent interest in "Victory Gardens" is also a reaction to temporary shortages in grocery stores (due to logistics, rather than supply) and fears that the food supply might be endangered by coronavirus. The First World War was also one of the first times in American history that a concerted effort to get ordinary people to plant kitchen gardens. Of course, part of that was because of the changing demographics of population. People in rural areas had almost always had kitchen gardens. But as more and more people moved into urban and suburban environments, and fresh food supplies became easier and cheaper to acquire, kitchen gardens became less necessary, and most people who could afford to focused on flower gardens instead. But the U.S. entrance into the war, with its commitment to feeding the Allies, came with very real fears that food would be in short supply. This was reinforced by rhetoric from Wilson and Herbert Hoover, the new U.S. Food Administrator, who knew that in the spring of 1917, existing crops would be inadequate to feed both Americans, their growing army, and the Allies without serious changes. Enter war gardens and voluntary rationing. Hoover was the brains behind the idea of voluntary rationing - he wanted Americans to show the world their personal fortitude and strength through voluntary efforts, including rationing. He also believed that the bureaucracy necessary to enforce mandatory rationing would not only be hugely expensive, it would also be ineffective. To lead by example, Hoover and the entire Food Administration were all volunteers. Rationing included refraining from eating wheat, meat, butter, and sugar whenever possible, and by the fall of 1917, "wheatless, meatless, and sweetless" days were implemented. Grain and flour substitutions, sugar substitutions, and vegetarian meals became more normalized during the war. The National War Garden Commission was also a voluntary organization, albeit a private, not public, one. Started by forestry magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, it encouraged Americans, especially school children, to plant "war gardens" (later renamed "victory gardens," a name that would resurface during WWII) which would provide fresh vegetables for ordinary people. Not only would this free up conventional food supplies, the production of local food would also free up transportation resources, which by the end of 1917 were becoming so congested that the United States temporarily nationalized its railroads. Spanish Influenza "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. And, of course, the obvious one. I've already written a bit about the Spanish Flu, but it bears noting that during the course of the 1918 pandemic, the government was reluctant to report real numbers or spread information about the severity of the pandemic because they were worried that it would endanger the war effort or reduce morale. Some cities, like Philadelphia, held enormous and patriotic Liberty Loan parades, allowing the virus to spread like wildfire. In fact, despite evidence that the influenza strain likely started in the United States, it wasn't until neutral Spain was infected, and its newspapers reported the real death toll, that the general public learned of the pandemic. Hence the name, "Spanish Influenza." Similar things are happening now, with the Trump Administration's initial reluctance to admit coronavirus was a serious problem because they feared the effect on the economy. Conflicting information in the media (and from the President) about the severity of the virus and the need for social distancing and stay at home orders have exacerbated the problem here in the U.S. More recently, a dearth of testing has led to some experts to conclude that the death toll is severely underreported. We are now also learning that China has likely suppressed or underreported the true infection rate and death toll from coronavirus. Thankfully, unlike 1918, when newspapers largely cooperated with government propaganda efforts (under threat of having their licenses revoked, effectively putting them out of business), modern information is more accessible and immediate than ever through the internet. Although sifting fact from fiction is a bit more difficult these days. ConclusionThere are a number of other Progressive Era similarities to modern life - women's rights, environmental conservation, voting rights, and income inequality, to name a few - that I chose not to include in this list largely because they were less immediately relevant to the coronavirus pandemic. To learn more about food in World War I, check out my Bibliography page, which was links to lots of great books. I hope you enjoyed this read. It certainly helped me organize my thoughts around these similarities and I hope that we can learn from the successes and failures of the past. That's all any historian can hope. Thanks for reading. Stay safe, stay home. If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

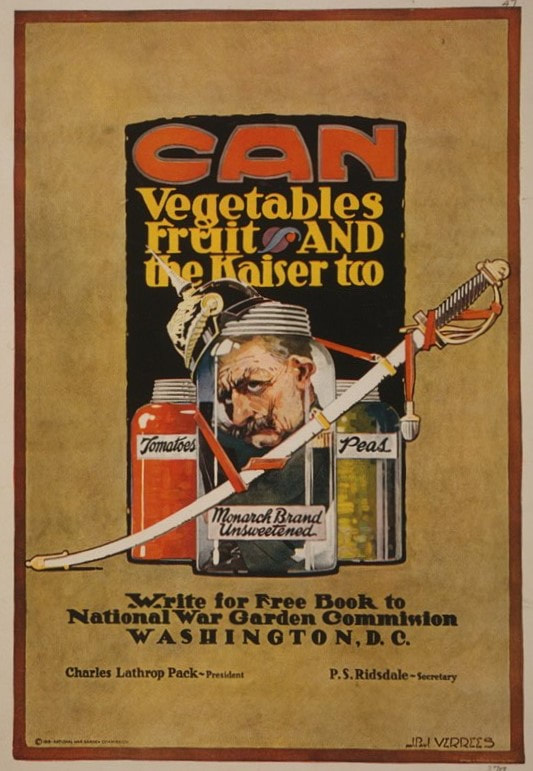

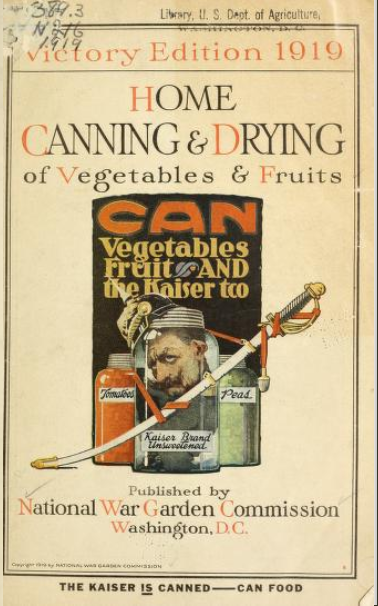

"Can Vegetables, Fruit, and the Kaiser, Too. Write for Free Book to National War Garden Commission, Washington, D.C." September is still preserving time, so I thought the next few World War Wednesdays would be about canning. This is another of my favorite World War I propaganda posters. Developed by the National War Garden Commission, the poster shows glass jars with zinc tops. Tomatoes at left, peas at right, and front and center, the profile of Kaiser Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia. His spiky German helmet and saber hang on the jar, which is labeled "Monarch Brand, Unsweetened." Eminently clever, the poster implies that home preserving has the power to defeat the might of the German Empire and the Kaiser himself. The First World War was one of the first times that ordinary Americans were called upon to preserve food in their homes. Many Americans, especially those in rural areas, were already canning and preserving the bounties of their home gardens. But as commercial canning became increasingly widespread, inexpensive, and safer, people with easy access to food retailers found it much easier to simply purchase canned goods, instead of going through the bother of putting up their own. Many people were still using the tried-and-true, but not necessarily safe, methods of their forebears. And while water bath canning was increasingly outpacing the traditional food preservation methods of fermentation, drying, and sealing jam with paraffin wax, water bath canning low acid vegetables still was not 100% safe. But as the government encouraged food conservation and food preservation, the National War Garden Commission stepped up to the plate. Founded (and funded) by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, the National War Garden Commission published a series of food preservation pamphlets that were used all over the country by home economists and women's groups to encourage home canning. The National War Garden Commission was also behind the school garden movement, but that's another post. The Commission would go on to produce a number of pamphlets on war gardening (renamed "Victory Gardening" post-war, a term that would be revived during the Second World War), including one pamphlet entitled "The War Garden Guyed," published in 1918. A clever play on words ("to guy" someone was to make fun of them, or ridicule), the "Guyed" contained cartoons, poems, and slogans both promoting and making fun of the gardening and food conservation movements. Submitted by newspaper editors, soldiers in the trenches, magazines, and ordinary people, the collection is quite a fun read, and not the only version the National War Garden created. "Raking the Gardener and Canning the Canner" predated "The War Garden Guyed" by one year - published in 1917, a quick turnaround indeed and indicates how quickly ordinary people adjusted to the idea of home gardening and canning. You can view almost all of the National War Garden Commission pamphlets on archive.org. In 1919, the National War Garden Commission used the "Can the Kaiser" poster image again, this time on their revamped "Home Canning & Drying of Vegetables and Fruits," rebranded "Victory Edition" post-war. At the bottom of the cover, it reads, "The Kaiser IS Canned." Although the fervor for home canning, thrift, and self-sufficiency continued into 1919 and 1920, by the time economic prosperity had returned full-force to give us the Roaring Twenties, most ordinary people who took up canning for the war effort abandoned it in victory. But I like to think that many of the food preservation lessons learned during the First World War would be revived and put to good use by the time the Second World War rolled around. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed