|

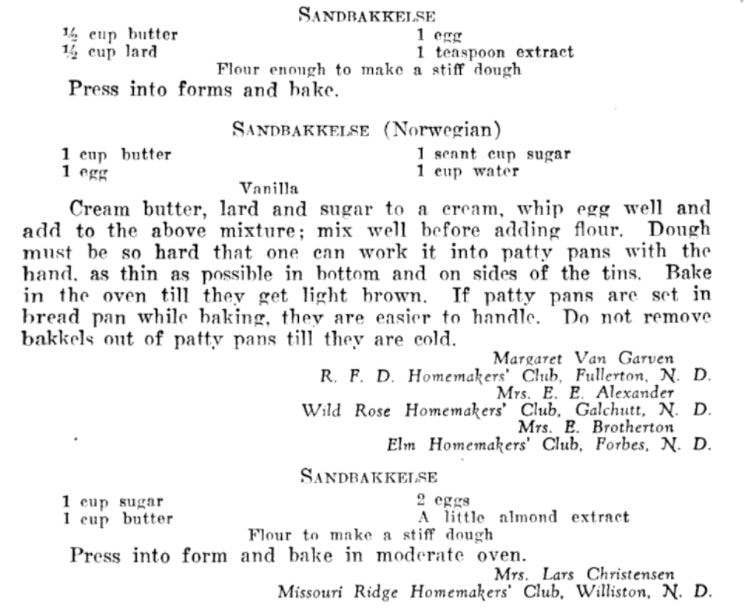

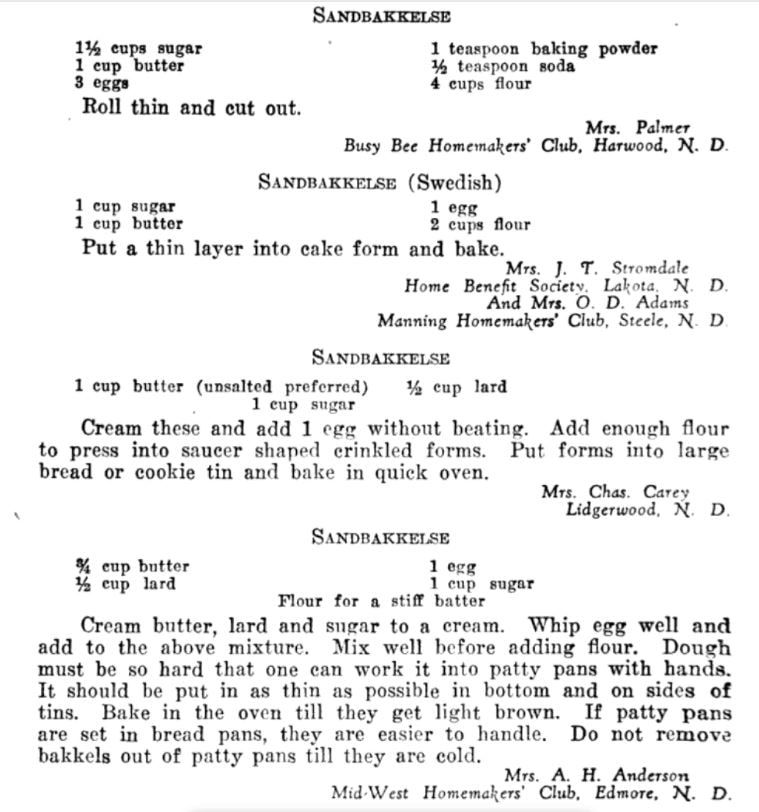

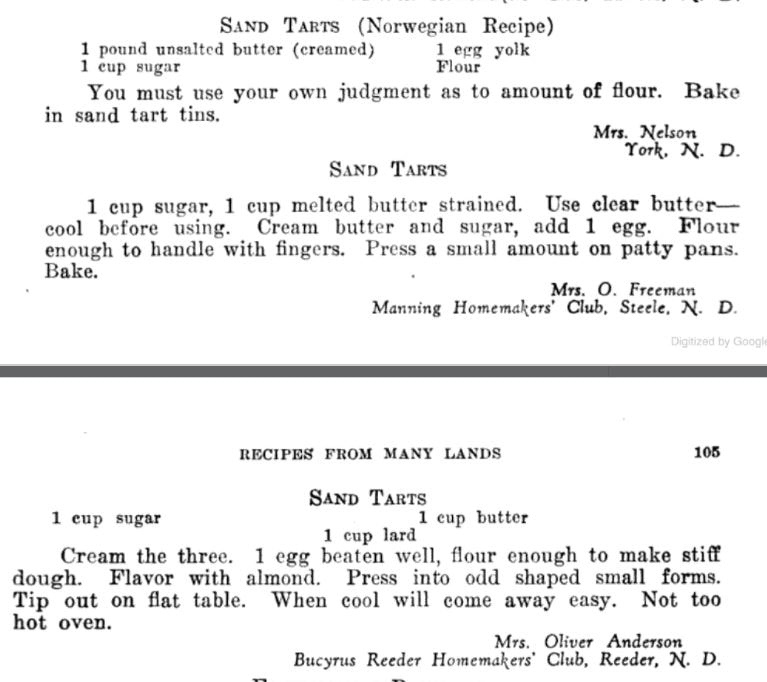

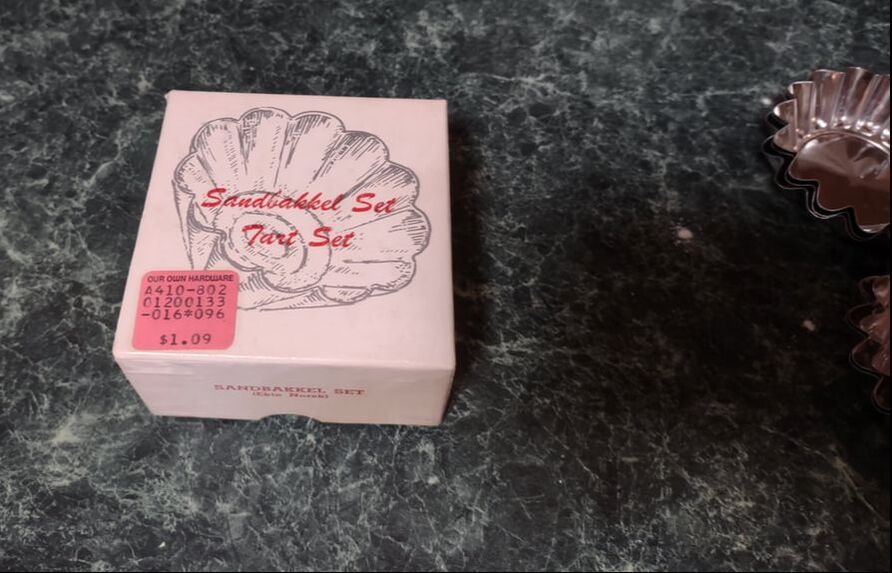

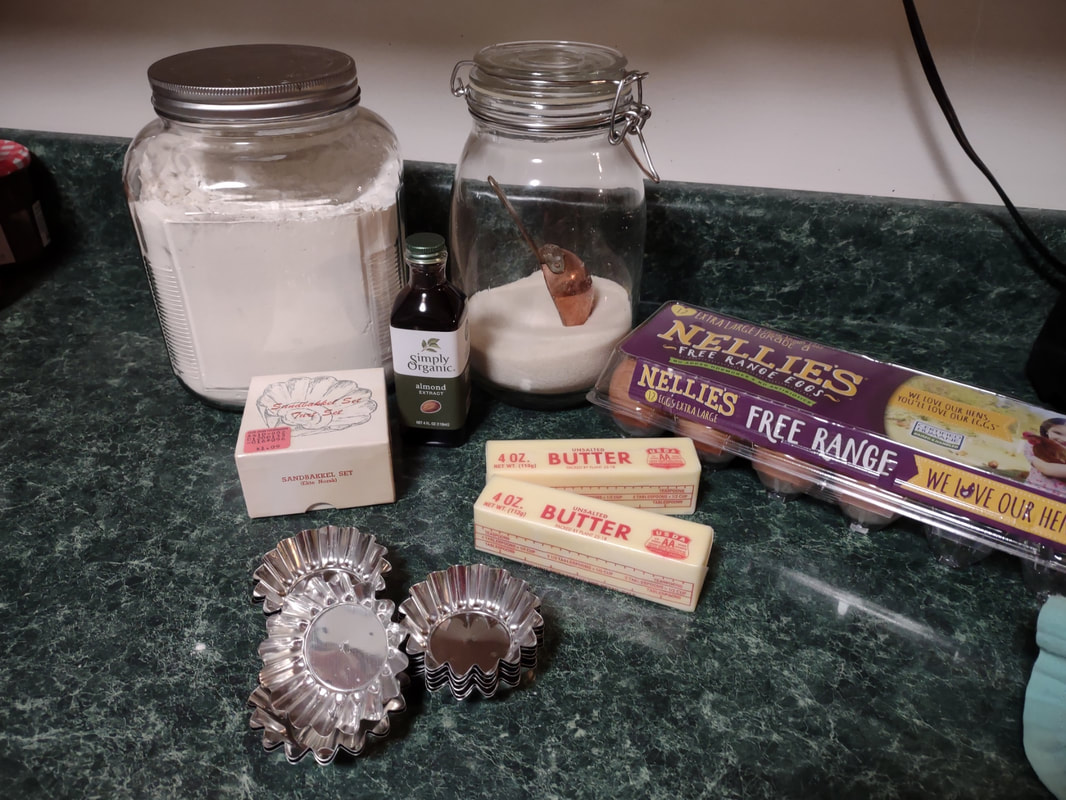

For a lot of Norwegian-Americans, sandbakkels (the plural in Norwegian is actually sandbakkelse, but we can Americanize) remind them of Christmas. The crisp, buttery cookies are essentially dense tart shells, similar to shortbread, but more crumbly. Meaning "sand pastry," sandbakkels are baked in special fluted tins and contain either ground almonds or more commonly in the U.S., almond extract. Despite the fact that they are usually served plain here in the states, those little tart shells just begged to be filled. So when I was planning my Scandinavian Midsummer Porch Party, I thought they would make the perfect little dessert. The problem was, what recipe to use? One of my best-loved talks is on the history of Christmas cookies, and I've got a whole section on Scandinavian ones. So I turned to my former research and remembered the PAGES of sandbakkel recipes from Recipes from Many Lands, a little cookbook of recipes submitted by North Dakota housewives and home economists around the state and published in July, 1927 as Circular 77 of the Agricultural Extension Division of North Dakota State University. I've clipped all the Sandbakkelse recipes (also Americanized to "Sand Tarts") and posted them below. The vast majority of these recipes are very similar - almost all call for a mixture of butter and lard, sugar, an egg or two, almond extract, and flour. The instructions are usually quite vague. Some don't even include amounts of flour. Some just say to press into tins and bake. So I decided to take the best advice from all the recipes and the Swedish Sandbakkelse recipe (which actually had measurements for everything) and go from there. But first, I had to find my sandbakkel tins! At some point I either stole them from my mother (she always had too many and never used them), but I had a little original box of vintage sandbakkel tins in mint condition hiding in the bottom of a kitchen drawer. Alas, I only had a dozen of them, so I had to make due with the recipe in other ways, which you'll see below. But how cute is this box? With the original hardware store price tag! Scandinavian Sandbakkelse Recipe (1927)The recipe is pretty straightforward, and if you don't have sandbakkel tins, never fear! There's a hack suggested in the historic recipes that I'll outline below. 1 cup softened butter (2 sticks) 1 cup granulated sugar 1 egg 1 teaspoon almond extract 2 cups flour (plus more to knead) Preheat the oven to 350 F. In a large bowl, cream the butter and the sugar together, then add the egg and extract and mix until smooth. Add the flour, a little at a time, until the dough starts to come together, then knead with the hands until smooth. Take half dollar sized pieces of dough and press into the tart tin, pressing the dough all the way out to the edge of the tin, but not over the edges. Make sure to press well to ensure good fluting. The dough is buttery enough that you won't need to grease the tins. Place tins on a sheet pan and bake 12-15 minutes or until golden brown. Let cool in the tins. Uhoh - you've still got a ton of dough left, and your sandbakkel tin set only came with 12 tins! What do you do? Well dear reader, you follow the advice of those sage 1920s North Dakota farm wives, who maybe didn't have sandbakkel tins either, and you press the dough into a pie plate, and bake it that way. And instead of filling the adorable individual tarts with jam and whipped cream, you fill a whole pie worth and cut it into slices to serve. Easy peasy! You could probably also use muffin tins, in a pinch. But the fluting is the pretty part, so if you can find sandbakkel tins, use them! I actually took a fair number of photos this time, so enjoy the process via the power of film: In all, the sandbakkelse were among the easiest of the Scandinavian cookies to make. Which is probably why in Norway they are traditionally the first Christmas cookie that kids help make. But they're not just for Christmas! They were delightful as a summer treat. You could also fill them with pastry cream, fresh fruit, chocolate, or whatever you like! But berry jam and whipped cream felt the most appropriate for Midsummer. If you'd like to buy your own sandbakkelse tins, Bethany Housewares makes the round kind, and you can get the fancy shapes from Norpro. And if you are a whipped cream fiend like my husband (and to a lesser extent me), and you admired the pretty piping, I can't recommend enough getting a professional, reusable whipped cream dispenser. We love this one. When you factor in buying the heavy cream and the nitrous oxide cartridges, they're not much cheaper than buying the disposable cans, but the whipped cream is some of the best you'll ever taste and you waste a lot less packaging. Plus the cream, once charged, keeps in the fridge for as long as the heavy cream was good. A little shake and it restores to fluffy deliciousness. Happy baking, happy eating! If you purchase anything from the links, The Food Historian gets a small commission! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

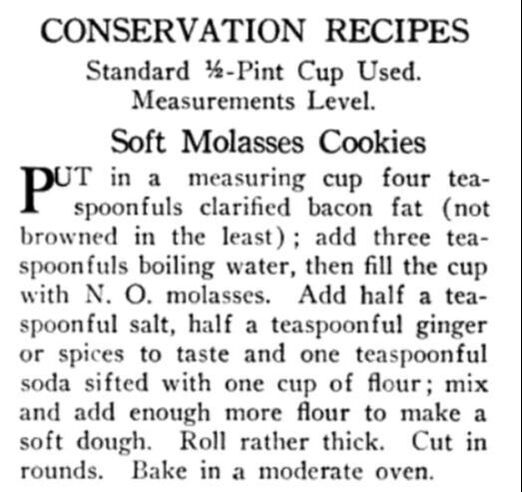

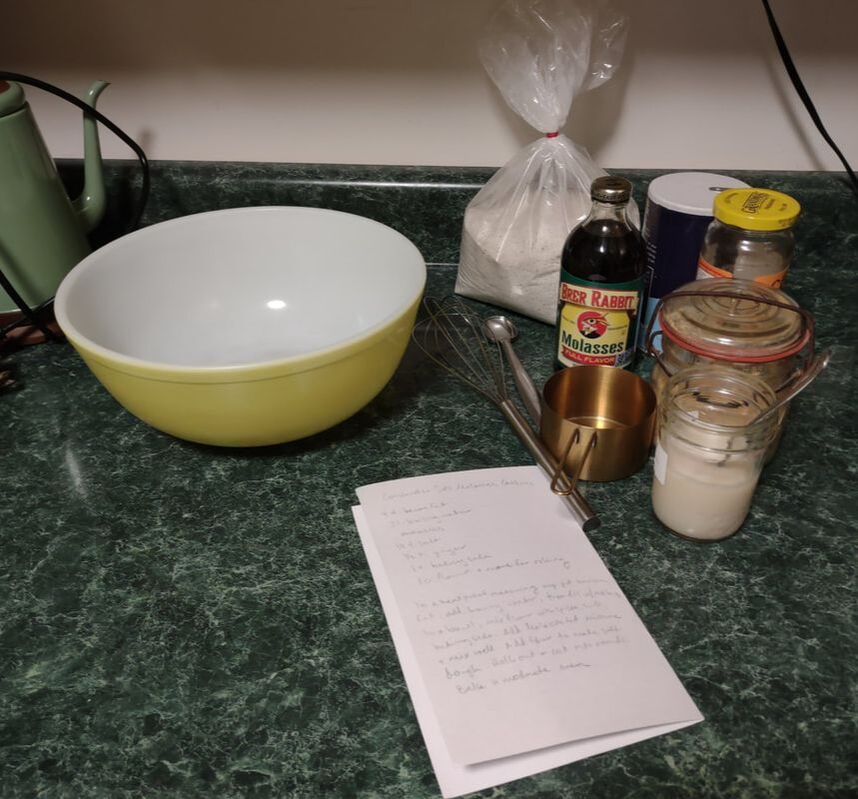

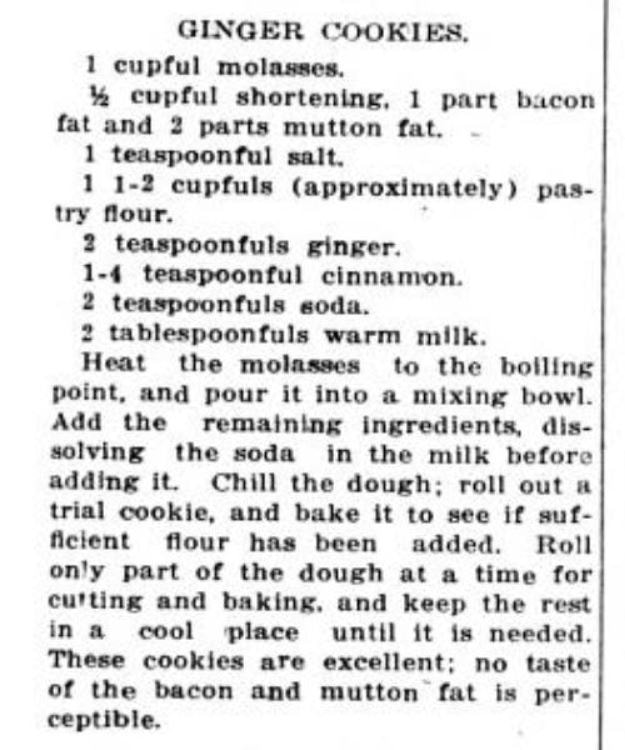

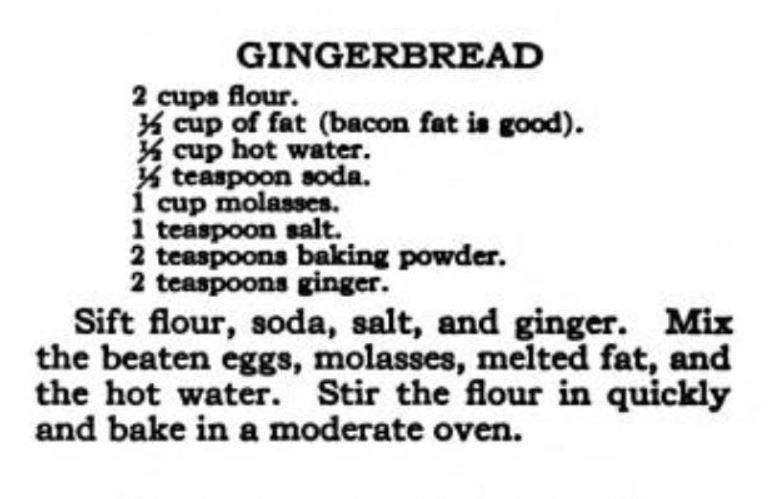

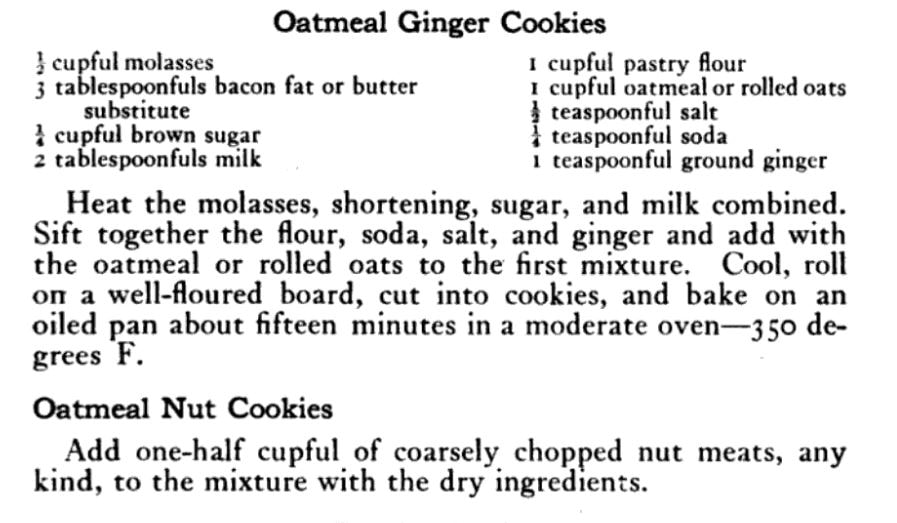

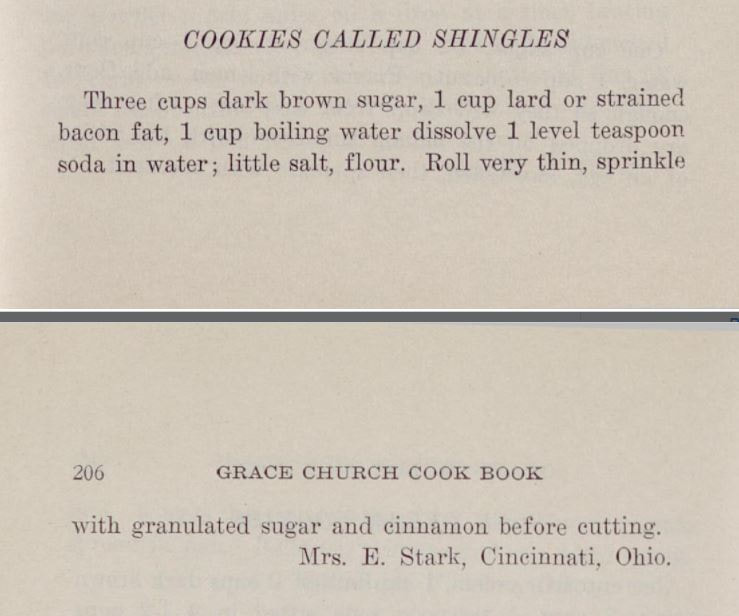

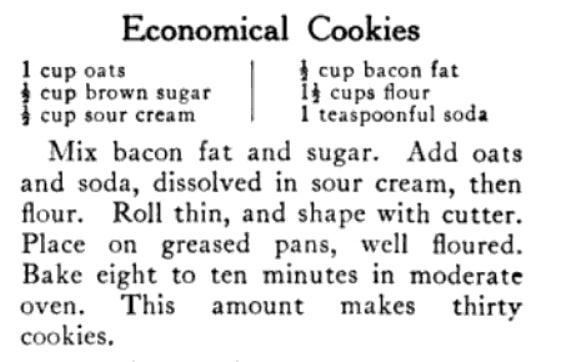

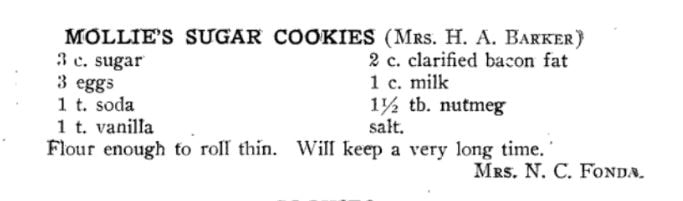

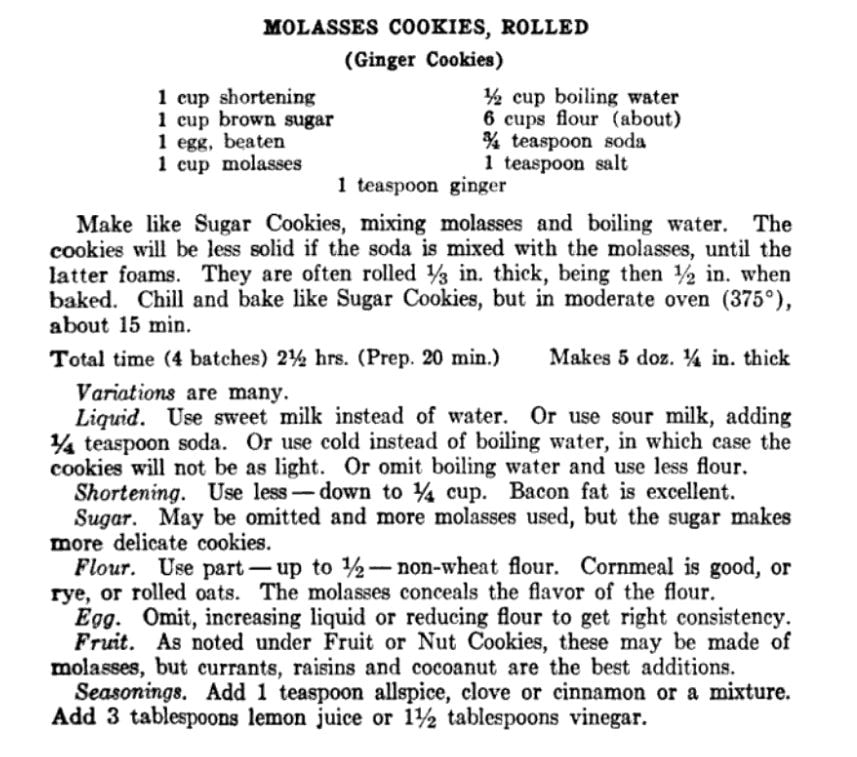

I first ran across bacon fat gingersnaps in the Christmas cookie collection the New York Times posted for December, 2021. Although I'm not a NYT Cooking subscriber, I did a google and found an article about the original recipe, which indicated the recipe was likely historic. Even though I'd just finished my Christmas cookies research, the bug bit again and the hunt was on. I found several historic recipes for bacon fat cookies, some of them gingery, some of them not (scroll to the bottom for the gallery of recipes), but because I am a World War I historian, I decided that the recipe I was most interested in at the moment was the "Soft Molasses Cookies" listed as a "Conservation Recipe" in the February, 1918 issue of American Cookery, formerly the Boston Cooking School Magazine. And it seemed appropriate to be baking them in February, 2022! The recipe is not written in a way we're used to today, but is fairly straightforward. It reads: Put in a measuring cup four teaspoons clarified bacon fat (not browned in the least); add three teapsoonfuls boiling water, then fill the cup with N.O. [New Orleans] molasses. Add half a teaspoonful salt, half a teaspoonful ginger or spices to taste and one teaspoonful [baking] soda sifted with one cup of flour; mix and add enough more flour to make a soft dough. Roll rather thick. Cut in rounds. Bake in a moderate oven. This recipe is sugarless, eggless, and butter-less, and it uses fats that might otherwise go to waste, making it the perfect conservation recipe during a time when Americans were asked to save wheat, sugar, meat, and fats for the war effort. The use of New Orleans molasses was specifically to save space on cargo ships and support American sugar production (molasses is a byproduct of sugar cane processing). By using bacon fat, normally a waste fat, Americans could save on lard and butter. Bacon Fat Soft Molasses Cookies (1918)I will admit that I started this recipe before I realized I was virtually out of all-purpose flour. And since I had a good deal of whole rye flour to use up, and I thought it in keeping with the spirit of the recipe to make this wheatless as well, I used all rye (although in the period rye was not considered an official substitute for wheat, largely because it was in fairly short supply). It did make a rather heartier cookie than I think was intended, but it worked just fine. Here's my translation of the original: 2+ cups flour (I used whole rye) 1 teaspoon baking soda 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger 4 teaspoons bacon fat 3 teaspoons boiling water a little less than 1 cup molasses Preheat the oven to 350 F. In a large mixing bowl, whisk together 1 cup flour, the baking soda, salt, and ground ginger. In a heat-proof measuring cup, place the bacon fat and add the boiling water. Then add molasses enough to make 1 cup. Pour into the flour mixture and beat well. Add more flour (about another cup) until a soft dough forms. You may need more flour as the dough will be very sticky. Knead in a little more flour as needed to make a dough that can be rolled without excessive stickiness. Flour your rolling surface well, and roll out the dough about a half inch thick, or a little thicker. Cut into rounds and bake on a parchment-lined baking sheet (to prevent sticking and save on grease!) at 350 F for 10-12 minutes. My batch rolled relatively thin made just short of 2 dozen largish cookies. Next time I would probably let them be a little thicker and I'd probably end up with a dozen and a half. Although these aren't crisp or particularly sweet, they do taste astonishingly close to the Archway brand of molasses cookies you can find very inexpensively in just about every grocery store. Soft, and a little cakey, with strong molasses flavor and just a hint of gingery spice. I couldn't really taste the bacon fat while they were still warm (though my husband claims he could), but the flavor will likely improve the next day. I did frost a few to dessert-them up a little. Just a few teaspoons of heavy cream mixed with some powdered/icing sugar. Shhh! Don't tell Herbert Hoover! Although these are quite soft right out of the oven, they will harden up as they cool, so be sure to store them in an air-tight container to help retain moisture. All things considered, I think this recipe turned out rather well for one that was supposed to be a bit of a privation during the war. Although I don't think it was UN-common to use bacon fat or drippings or any other animal fats as shortening in baking in the 19th century (indeed in the 1800s "shortening" just meant any kind of solid fat - remember we don't get vegetable shortening until the 1870s), we don't really see bacon fat specifically called out in cookbooks until the 1910s. One reason is likely that bacon was an increasingly popular breakfast food. Oscar Mayer, in particular, started selling pre-packaged sliced bacon in 1924. Breakfast was rebranded in the 1920s away from stodgy porridges and even health-food cold cereals and toward bacon, eggs, and tableside electric appliances that made things like waffles, fresh-squeezed orange juice, coffee, and toast. All that bacon frying meant that cooks had a surfeit of grease, and frugal cooks would hate to waste it. And while bacon fat is perfect for frying potatoes into hash, there's only so many things you can fry in bacon fat. Hence, the baking recipes. As you can see from the collection below, they're all for 1915 and later, with most in the 1920s. Bacon fat was saved in WWII as well, but housewives were just as likely to save the fat for munitions than bake with it. Once animal fats were connected to heart disease in the 1950s, bacon took a back seat in the United States until its revival in the 2000s (largely coinciding with the popularity of the Atkins Diet). We don't make bacon all that often. Usually it's with a big breakfast or brunch I make on the weekends. But I've made a point lately to save the fat. If you bake your bacon in the oven like I do (450 F for 10-15 mins), you can just pour the fat off of the baking sheet and into a glass jar. Keep the jar in the fridge and you'll have a smoky, salty fat for flavoring beans, potatoes, eggs, and yes, even molasses cookies. Which bacon fat recipe do you think I should try next? I'm leaning towards the sugar cookies... The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Just leave a tip |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed