|

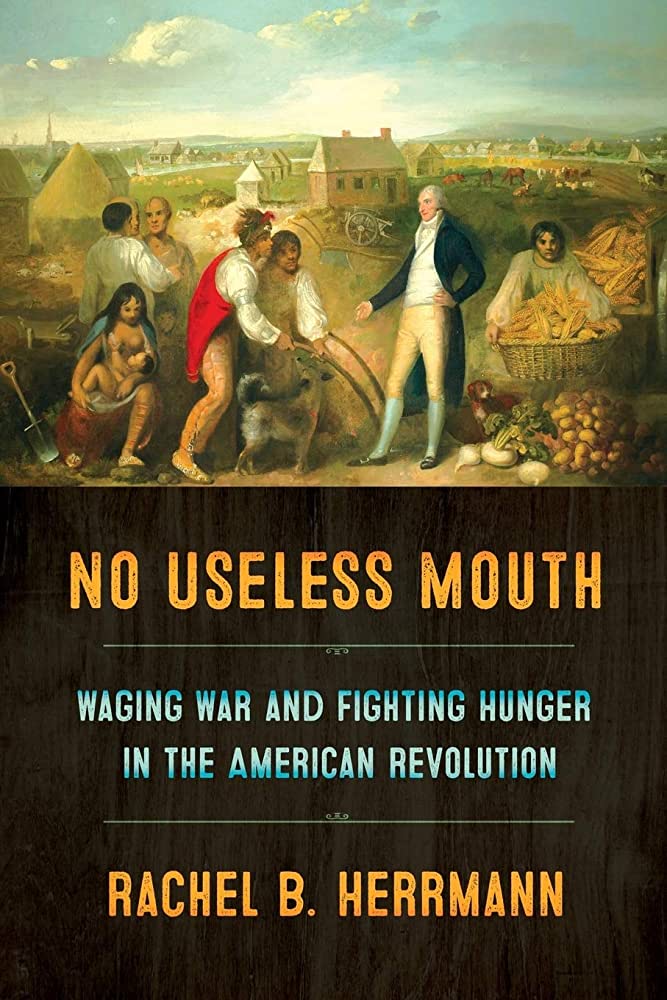

This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. This may be the longest I have ever taken to write a book review. I first received this book and the invitation to review it for the Hudson Valley Review in the fall of 2021. As many of you know, 2022 was a rough year for me, for many reasons, but I finally turned in the review in February of 2023. A few days ago, I received my copy of the Review and now that my book review is in print, I feel I can share it here! This edition of the Review is great, with several excellent articles and other book reviews, so if you manage to find a copy, please check it out! Back issues are often posted digitally. Without further ado, the review: In the historiography of the American Revolution, one can be forgiven for thinking every possible topic has been covered. But Rachel B. Herrmann’s new book No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution brings new nuance to the period. In it, Herrmann argues that food played a decisive role in the shifting power dynamics between White Europeans, Indigenous Americans, and enslaved and free Africans and people of African descent. She looks at the American Revolution through an international lens, covering from 1775 in the various colonies through to the dawning of the 19th century in Sierra Leone. The book is divided into eight chapters and three parts. Part I, “Power Rising,” introduces us to the ideas of “food diplomacy,” “victual warfare,” and “victual imperialism” within the context of the American Revolution. Contrasting the roles of the Iroquois Confederacy in the north and the Creeks and Cherokees in the South, Herrmann brings additional support to the idea that U.S. treaties with Indigenous groups should join the pantheon of diplomacy history, while centering food and food diplomacy within the context of those treaties. She also addresses how Indian Affairs agents communicated with various Indigenous groups – with varying success. Part II, “Power in Flux,” addresses the roles of people of African descent in the American Revolution, focusing primarily on Black Loyalists as they gained freedom through Dunmore’s Proclamation and the Philipsburg Proclamation. Black Loyalists fought on behalf of the British as soldiers, spies, and foraging groups, and escaped post-war to Nova Scotia with White Loyalists. Part III, “Power Waning,” summarizes what happened to Indigenous and Black groups post-war, focusing on the nascent U.S. imperialism of Indian policy and assimilation and the role food and agriculture played in attempts to control Native populations. It also argues that Black Loyalists adopted the imperialism of their British compatriots in attempts to control food in Sierra Leone, ultimately losing their power to White colonists. Part III also includes Herrmann’s conclusion chapter. No Useless Mouth is most useful to scholars of the American Revolution, providing good references to food diplomacy while also highlighting under-studied groups like Native Americans and Black Loyalists. However, lay readers may find the text difficult to process. Herrmann often makes references to groups and events with little to no context, assuming her readers are as knowledgeable as she. In addition, the author appears to conflate Indigenous groups with one another, making generalizations about food consumption patterns and agricultural practices without the context of cultural differences. In focusing on the Iroquois Confederacy and the Creeks/Cherokee, Herrmann also ignores other Native groups, despite sometimes using evidence from other Indigenous nations to support her arguments. For instance, when discussing postwar assimilation practices with the Iroquois in the north and the Creeks and Cherokee in the south (often jumping from one to another in quick succession), she cites Hendrick Aupaumut’s advice to Europeans for dealing successfully with Indigenous groups. But she fails to note that Aupaumut was neither Iroquois, Creek, nor Cherokee, but was in fact Stockbridge Mohican. The Stockbridge Mohicans were a group from Stockbridge, Massachusetts that was already Christianized prior to the outbreak of the American Revolution. They fought on the Patriot side of the war, with disastrous consequences to the Stockbridge Munsee population, and ultimately lost their lands to the people they fought to defend. Without knowledge of this nuance, readers would accept the author’s evidence at face-value. Herrmann’s strongest chapters are on the Black Loyalists, and her research into the role of food control in both Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone is groundbreaking, but even those chapters have a few curious omissions. In discussing Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, which was issued in 1775 in Virginia and targeted enslaved people held in bondage by rebels, freeing those who were willing to join the British Army. The chapter then focuses primarily on the roles of enslaved people from the American South. But Herrmann also mentions briefly the Philipsburg Proclamation, issued in 1779 in Westchester County, NY, which freed all people held in bondage by rebel enslavers who could make it to British lines. That proclamation arguably had a much larger impact on the Black Loyalist population, as it also included women, children, and those above military age, thousands of whom streamed into New York City, the primary point of evacuation to Nova Scotia. And yet, Herrmann does not mention at all enslaved people in New York and New Jersey, where slavery was still very active throughout the American Revolution and well into the 19th century. In the chapter on Nova Scotia, Herrmann also mentions that White Loyalists brought enslaved people with them, still held in bondage. Neither Dunmore’s nor the Philipsburg proclamations freed people held in bondage by Loyalists, and yet they get only a brief mention. Her chapters on Indigenous-European relations are extremely useful for other historians researching the period, but would have been improved with additional context on land use in relation to food. Herrmann often references famine, food diplomacy, and victual warfare in these chapters, without addressing the impact of land grabs and disease on the ability of Indigenous groups to feed themselves. She references, but does not fully address the need of European settlers to expand settlement into Indian Country as a motivating factor in war and postwar diplomacy. Finally, while the focus of the book is specifically on the roles of Indigenous and Black groups in the context of food and warfare, the omission of victual warfare by British and American troops and militias, especially in “foraging” and destroying foodstuffs of White civilian populations throughout the colonies seems like a missed opportunity to compare and contrast with policies and long-term impacts of victual warfare toward Indigenous groups. In all, this book is a worthy addition to the bookshelves of serious scholars of the American Revolution, especially those interested in Indigenous and Black history of this time period, but it also leaves room for future scholars to examine more closely the issues Herrmann raises. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

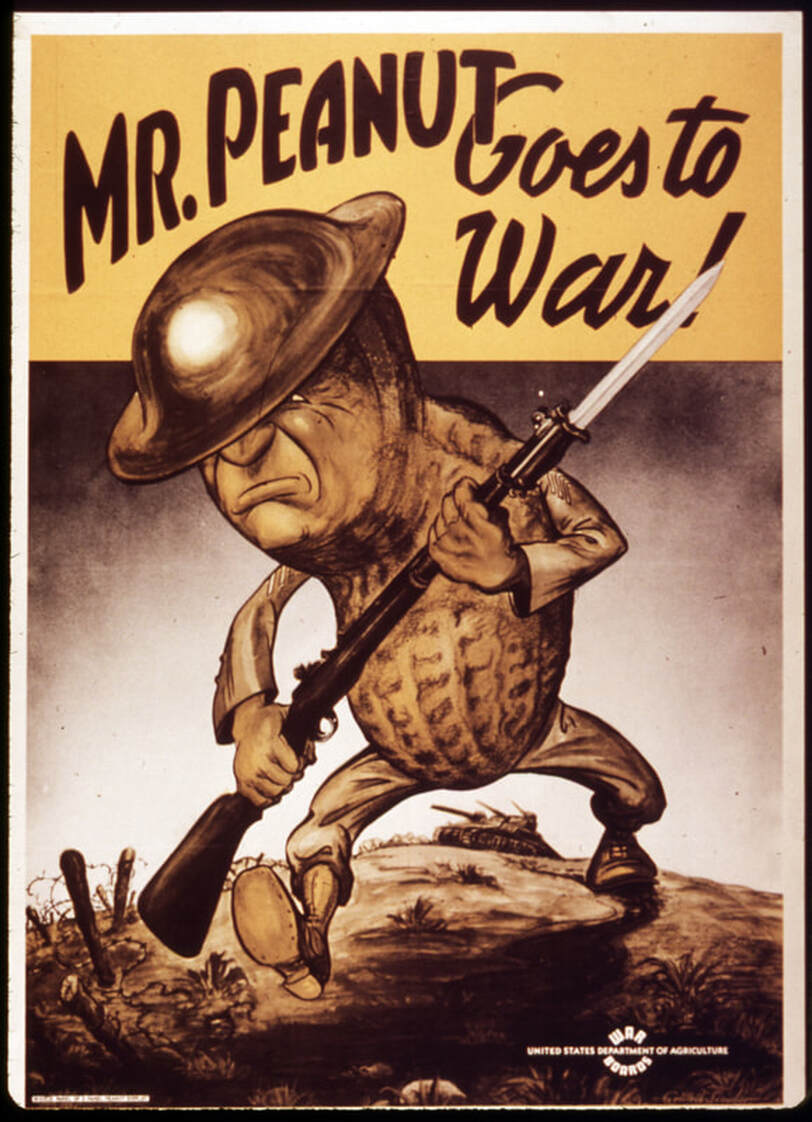

When you think of rationing in World War II, you may not think of peanuts, but they played an outsized role in acting as a substitute for a lot of otherwise tough-to-find foodstuffs, mainly other vegetable fats. When the United States entered the war in December, 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the dynamic of trade in the Pacific changed dramatically. The United States had come to rely on cocoanut oil from the then-American colonial territory of the Philippines and palm oil from Southeast Asia for everything from cooking and the production of foods like margarine to the manufacture of nitroglycerine and soap. Vegetable oils like coconut, palm, and cottonseed were considered cleaner and more sanitary than animal fats, which had previously been the primary ingredient in soap, shortening, and margarine. But when the Pacific Ocean became a theater of war, all but domestic vegetable oils were cut off. Cottonseed was still viable, but it was considered a byproduct of the cotton industry, not an product in and of itself, and therefore difficult to expand production. Soy was growing in importance, but in 1941 production was low. That left a distinctly American legume - the peanut. Peanuts are neither a pea nor a nut, although like peas they are a legume. Unlike peas, the seed pods grow underground, in tough papery shells. Native to the eastern Andes Mountains of South America, they were likely introduced to Europe by the Spanish. European colonizers then also introduced them to Africa and Southeast Asia. In West Africa, peanuts largely replaced a native groundnut in local diets. They were likely imported to North America by enslaved people from West Africa (where peanut production may have prolonged the slave trade). Peanuts became a staple crop in the American South largely as a foodstuff for enslaved people and livestock, but the privations of White middle and upper classes during the American Civil War expanded the consumption of peanuts to all levels of society. Union soldiers encountered peanuts during the war and liked the taste. The association of hot roasted peanuts with traveling circuses in the latter half of the 19th century and their use in candies like peanut brittle also helped improve their reputation. Peanuts are high in protein and fats, and were often used as a meat substitute by vegetarians in the late 19th century. Peanut loaf, peanut soup, and peanut breads were common suggestions, although grains and other legumes still held ultimate sway. George Washington Carver helped popularize peanuts as a crop in the early 20th century. Peanuts are legumes and thus fix nitrogen to the soil. With the cultivation of sweet potatoes, Carver saw peanuts as a way to restore soil depleted by decades of cotton farming, giving Black farmers a way to restore the health of their land while also providing nutritious food for their families and a viable cash crop. During the First World War, peanut production expanded as peanut oil was used to make munitions and peanuts were a recommended ration-friendly food. But it was consumer's love of the flavor and crunch of roasted peanuts that really drove post-war production. By the 1930s, the sale of peanuts had skyrocketed. No longer the niche boiled snack food of Southerners or ground into meal for livestock, peanuts were everywhere. Peanut butter and jelly (and peanut butter and mayonnaise) became popular sandwich fillings during the Great Depression. Roasted peanuts gave popcorn a run for its money at baseball games and other sporting events. Peanut-based candy bars like Baby Ruth and Snickers were skyrocketing in sales. And roasted, salted, shelled peanuts were replacing the more expensive salted almonds at dinner parties and weddings. Peanuts were even included as a "basic crop" in attempts by the federal government to address agricultural price control. They were included in the 1929 Agricultural Marketing Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, and an April, 1941 amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. Peanuts were included in farm loan support and programs to ensure farmers got a share of defense contracts. By the U.S. entry into World War II, most peanuts were being used in the production of peanut butter. And while Americans enjoyed them as a treat, their savory applications were ultimately less popular as an everyday food. But their use as source of high-quality oil was their main selling point during the Second World War. Peanut oil was the primary fuel in Rudolf Diesel's first engine, which debuted in 1900 at the Paris World's Fair. Its very high smoke point has made it a favorite of cooks around the world. During the Second World War peanut oil was used to produce margarine, used in salad dressings and as a butter and lard substitute in cooking and frying. But like other fats, its most important role was in the production of glycerin and nitroglycerine - a primary component in explosives. Which brings us to our imagery in the above propaganda poster. "Mr. Peanut Goes to War!" the poster cries. Produced by the United States Department of Agriculture, it features an anthropomorphized peanut in helmet and fatigues, carrying a rifle, bayonet fixed, marching determinedly across a battlefield, with a tank in the background. Likely aimed at farmers instead of ordinary households, Mr. Peanut of the USDA was nothing like the monocled, top-hatted suave character Planter's introduced in 1916. This Mr. Peanut was tough, determined to do his part, and aid in the war effort. The USDA expected farmers (including African American farmers) to do the same. Further Reading: Note: Amazon purchases from these links help support The Food Historian.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed