|

If you're at all involved in small historical organizations, however peripherally, you know that talking about digitization can sometimes be a dangerous subject. People think that by "giving our stuff away for free," internet denizens will steal it, publish books, and profit. Alas, nothing could be farther from the truth (seriously - the research, and the metadata, backs it up). But there's another important angle here that isn't often discussed.

It's one I realized the other day when I was writing a research proposal for a fellowship. Until now my research has been confined to photographs of an archival scrapbook (that I took myself) and whatever digital scraps I can find. From journal articles you can now (kind of) read for free on JSTOR (there's a 3 article per 14 day limit) to Google Books to archive.org and all the digitized archival material in between (from university archives, library archives, and digital repositories the nation over). But wait, why can't I just spend all my free time in an archive, poring over records, you ask? Two reasons: 1. I'm not in a PhD program nor am I a college professor, so I don't have research funding. Although even my friends in PhD programs don't necessarily get research stipends. 2. Because I'm not in a PhD program, and I'm not a professor, nor am I retired, that means I have a "real" job. Which means taking time off to visit archives, which are often only open limited daytime hours on weekdays, is not really an option. Even though I'm currently applying for a research stipend, if I get it I will not be able to take advantage of the full 6 weeks they offer to study at the archive. Because I just can't take 6 straight weeks off from work. I'm not even sure I can take 2 weeks off from work. But the fellowship is designed for college professors with summers off. SIGH. I'm hoping they'll allow me to guerrilla-photograph most of it and study from home. We'll see. If I get it. And that made me realize - digitization is really effing important. Not just for historical organizations to share their collections with the public (which is the whole point of having collections in the first place), but for researchers too poor and/or too busy to visit the archives in person. Small historical institutions have proven, time and again, to have collections that are nationally significant, rare, and/or which illuminate previously unstudied bits of history. And that makes them incredibly important. Because the future of historical study is not going to be the 1950s style of history where you write sweeping, 1,000 page histories of the Roman Empire anymore. The future of historical study is finding these small stories and fitting them, and their significance, into the larger context. Which is what I'm trying to do. But it would be a whole lot easier if everything was digitized. So the next time you hear someone complain about digitization, tell that person they are fueling the fevered research of time- and cash-impoverished researchers everywhere.

0 Comments

Happy Presidents' Day, everyone! Originally celebrated on February 22nd, which is George Washington's birthday, President's Day was consolidated with Abe Lincoln's in 1971 and every year food blogs are inundated by everything cherry in George's honor (poor Abe gets little mention at all, and you can just forget about all the other Presidents). The story goes that little George "barked" a cherry tree as a child and couldn't "tell a lie" to his father, admitting the deed. Cherries have been a symbol of George ever since. But did the poor barked cherry tree actually exist? Most historians say no, given that the story first appeared in a later edition (but not the first) of a biography published some years after Washington's death. Although some historians argue that it is, in fact, likely to be true, given that none of George's (i.e. Martha's) children ever disputed it. But did George ACTUALLY like cherries? The story goes that cherry pie was his favorite, and thus cherry pies are served in his honor all over the country. But was it? A search of Washington's papers for "pie" brings up only a couple of mentions, all referring to "Christmas pie." Searching for "cherry" brings up hundreds of hits - all about Washington planting cherry trees of all difference varieties at Mount Vernon. So he certainly liked cherries. But cherry pie? Pie was a common way to turn fruit into dessert in the 18th century and was much easier to make in the days of open-hearth cooking than the more complicated cakes. Cakes were also much more expensive, being leavened with numerous, long-beaten eggs and calling for large amounts of butter, sugar, and spices. Pies, on the other hand, were made with lard and a little flour, with a cooked fruit filling, which may or may not have been sweetened. Pies could also be sweetened with the much cheaper honey, molasses, or maple syrup. They were also a lot faster to make and less likely to scorch in a dutch oven over coals or inside a beehive oven. So it is possible that Washington ate a fair number of cherry pies in his day. But the thing about cherries is that they aren't even remotely in season in February. Martha Washington did record a recipe for preserved cherries. And cherry bounce, a sort of homemade cherry brandy, was popular in the 18th century. But cherry pie for George's birthday? Not likely, unless it was made with those preserved cherries. If you ask the folks at Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site in Newburgh, NY (not too far from where I live), they'll tell you that Washington's favorite food was walnuts. Which crops up (no pun intended) in the tree planting sections of Washington's papers just as often, if not more so, as cherry trees. Another Washington legend says he could crack walnuts with his bare hands. Which with English walnuts (his favorite) is quite easy. Native American black walnuts, however (those most readily available to George), are a different story. Most people crack those by running their cars over them. With their British heritage, George and Martha may have made pickled walnuts, which are made in June when black walnuts are still green and the nut hulls haven't fully formed yet. The pickled green nuts (recipe here) are eaten whole (hull and all!) with cheese. In the 18th century cheese and nuts with fruit was a common "dessert course." They'd probably go great with some preserved cherries and cherry bounce. If you'd rather celebrate George with a dessert, try the slightly more accurate Martha Stewart's walnut pie (though what you'd substitute for corn syrup I'll never know). Or bake Martha Washington's "Great Cake," which would have been eaten at Christmastime (maybe a few slices were left by February?). But keep in mind that, according to Martha's grandson Custis, George may not have even liked dessert all that much. Custis wrote, "He ate heartily, but was not particular in his diet, with the exception of fish, of which he was excessively fond. He partook sparingly of dessert, drank a home-made beverage, and from four to five glasses of Madeira wine." Maybe fish in Madeira would be a better dish to celebrate Washington? Certainly cherry bounce counts as "a home-made beverage." Really, whole walnuts, cheese, and preserved cherries with a glass of cherry bounce or Madeira would be the most accurate "dessert" to reflect George's predilections. If you'd rather, go ahead and celebrate Abe Lincoln instead. Apples, corn cakes, bacon, and gingerbread men were among his favorites. If you'd like to know more about Abe and his penchant for helping Mary in the kitchen, check out Rae Katherine Eighmey's Abraham Lincoln in the Kitchen or listen to this interview from NPR. However you celebrate our past Presidents, just remember that when it comes to the past, culinary or otherwise, our American mythology isn't always accurate. Happy eating. Happy Presidents' Day. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! No really.

You would think that with a field title like "food history," that historians writing books on that topic would be a given. Not so. In fact, I think it would be safe to say that at least 50% of the books marketed today as "food history" books are, in fact, written by people with little to no historical training at all. Journalists, scientists, home cooks, chefs, literature majors who like food, and people who think history is cool. Which is great! I love people who love history. I just don't think that they should necessarily be writing authoritative food histories. Maybe that makes me a heretic. After all, I'm also the type of historian who refuses to use the word "an" before the word "historian." I can't help it - I'm an Americanist. We pronounce the aitch. But frankly, with a few notable exceptions, most food history books I've read as of late have been disappointments. In fact, the whole field is a bit of a disappointment. Many publishers seem to think that the history of a particular ingredient qualifies as "food history." Or the history of a recipe, or an ethnic cuisine. And these books may, indeed, be writing about the histories of these individual bits. But that does not, in and of itself, qualify as food history. Because unlike most books published today, REAL food history is history first. If you wrote a science book about the ocean and spent more time describing the marine wildlife than you did actually presenting your research, you'd be laughed out of the academy. But this happens to food history all the time. Authors get caught up in describing things without actually analyzing them. And that's where the trouble lies. History is all about taking primary sources, putting them in context, and drawing inferences about the lives of the people who lived in the past, and what their lives and actions mean for the present. The missing "ingredient" from most modern food histories? The people. After all, what is the history of the tomato without people? Tomatoes didn't domesticate themselves. In fact, without the context of humanity and its quest for edibles, tomatoes really don't matter at all. True history answers the "so what?" question in a way that many modern food histories just don't seem to. Even some of the better histories written by academics which try to make themselves relevant by making connections to modern issues don't do a particularly good job of it. These attempts at relevancy often seem like something tacked on the end of the book at the behest of the publisher, rather than being rooted in the inquiry itself. Because I'm more public historian than true member of the academe, for me the study of food and especially food history should help us illuminate our own ideas, pre-conceived notions, and biases about food, agriculture, and eating. WHY did we domesticate tomatoes from a tiny wild fruit? WHY did our food production system shift from home-based production to factory-based? WHY do we struggle so much with figuring out what is "healthy" to eat? Food history is not an island. You need the context of agricultural history, transportation history, culinary history, ethnic history, political/policy history, the history of what is in fashion, the history of etiquette and manners, women's history, slave and servant history, the history of science.... I could go on. Food is an inextricable part of our lives. It is literally the ONE THING that connects all humans across all times and spaces. Even the deaf, blind, mute, and/or paralyzed still need to eat and drink. It connects us in a way that language, art, music, dance, storytelling, and just about any other form of communication cannot. To analyze it without context is just criminal. In summation - if you want to write about food history, please do! But give the study of history just as much or more attention as you do the study of food. And publishers? Please vet your food history manuscripts by academic historians. Everyone, including future researchers, will thank you.

Okay folks, after over a month of intensive research, part ONE of a two-part episode is now ready. January and New Year's resolutions was the original inspiration for this examination of health food in America, but then I went down the rabbit hole of research and still haven't finished (which is what part two is for).

Recipes

Despite being a bit of a quack, I really like a lot of Gayelord Hauser's cooking, if not his medical advice. Here are a few interesting recipes that seem more "modern" than 1940s.

Avocado Cream Dressing - The Gayelord Hauser Cookbook 1 cup avocado pulp pinch of vegetable salt 2 tbsp. honey 1 cup heavy cream Rib the avocado through a sieve or fruit press. Add the salt and honey and mix thoroughly. Whip the cream and fold in the avocado pulp. Serve with fruit salads. Especially delicious on molded grapefruit. Complexion Salad - The Gayelord Hauser Cookbook 1 cup carrots, finely shredded 8 tbsp. pineapple juice 1 cup celery, finely chopped 1 cup cabbage, finely shredded 3/4 cup red apples, diced Saturate the ingredients with pineapple juice. When cold, arrange on crisp leaves of lettuce or escarole and garnish with sprigs of water cress. Pine-Nut Steak - The Gayelord Hauser Cookbook 3/4 cup finely shredded carrots 1/2 cup ground or crushed pine nuts 2 eggs, well beaten 1/2 cup dry whole-wheat bread crumbs 1/2 tsp. dried sage 1/4 tsp celery seed 1 tsp. vegetable salt 2 tsp. melted butter Add the carrots and nuts to the well-beaten eggs and mix thoroughly. Add the remaining ingredients and mix well. Turn out onto a small greased dripping pan and spread in a sheet, or drop by heaping serving-spoonfuls onto a buttered pan for individual steaks. Bake in a moderate oven (350 F) until nearly firm - 15-20 minutes. Finish cooking under the broiler to brown on top. Garnish with any fresh greens and serve with lemon butter. Hauser Broth 1 cup finely shredded carrots 1 cup finely shredded celery, leaves and all 1/2 cup shredded spinach 1 tbsp. chopped parsley 1 large onion, chopped 1 large celery root, chopped (whenever you can get it) 1 heaping tsp. vegetable salt 1 qt. water Put all these shredded vegetables in cold or warm - not hot - water. Simmer over a low flame for not more than 30 minutes. Then turn off the heat, add your heaping teaspoonful of vegetable salt, and let stand 10 minutes. Strain. This gives you the basic stock from which you can concoct endless varieties of vegetable broth. Bibilography

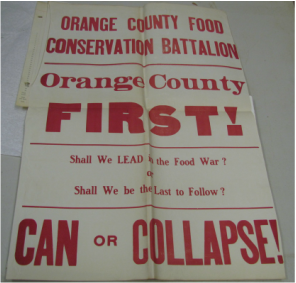

The History of the Calorie in Nutrition

A History of Rickets in the United States In Raising the World's IQ, the Secret's in the Salt For that Healthy Glow, Drink Radiation! The Strange Fate of Eben Byers How Cultists, Quacks, and Naturemenschen Made Los Angeles Obsessed with Healthy Living California: For Health, Pleasure, and Residence - a book for travellers and settlers by Charles Nordhoff Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science by Martin Gardner Eat and Grow Beautiful by Gayelord Hauser The Gayelord Hauser Cookbook, by Gayelord Hauser Gayelord Hauser New York Times Obituary  I am proud to announce that I will be doing a talk entitled, "Can or Collapse: The Orange County Food Preservation Battalion and Their 1917 Erie Railroad Demonstration Train." The talk will be one of several World War I focused talks and part of the Great War Commemoration at Museum Village in Monroe, NY on Saturday, April 4th, 2016. No specific time yet, but I may or may not also be coordinating with Red Cross and canning reenactors and giving tastings of dehydrated and rehydrated spinach and carrots (which the Orange County Food Preservation Battalion actually did on their demonstration train). Other activities that day include costumed WWI reenactors and displays of WWI historic artifacts. The event takes place from 11 am to 3 pm. Cost is $12 for adults, $10 for seniors, $8 for kids aged 4-12. Kids 4 and under and veterans get in free. Stay tuned for details! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed