|

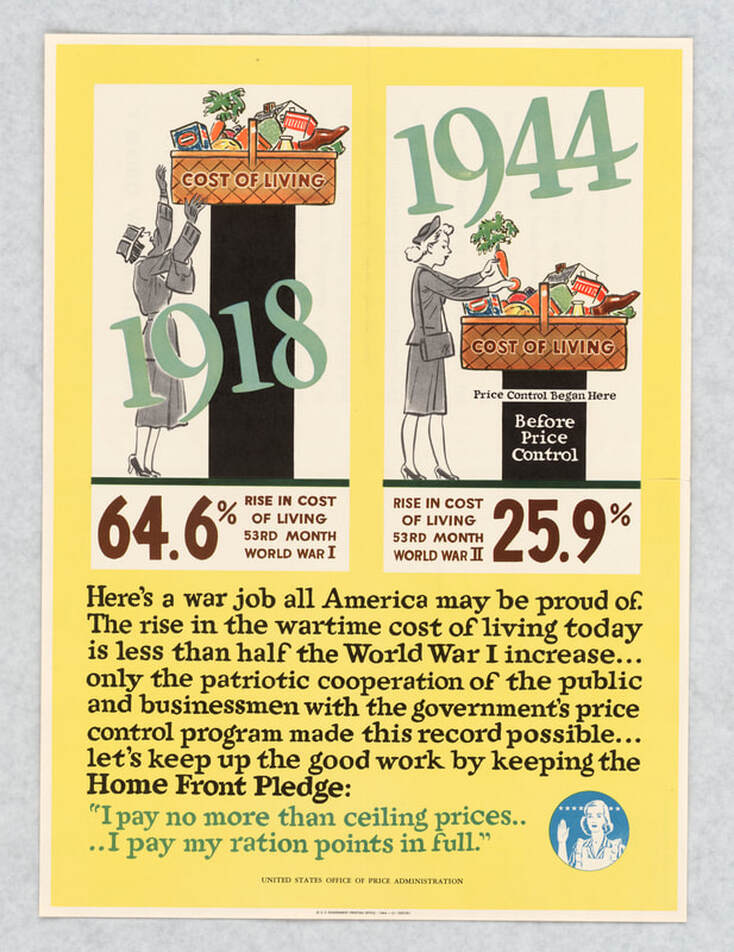

With all the talk of price increases and inflation these days, it's interesting to look to how these things were handled in the past. On a previous World War Wednesday, I talked about the differences between World War I and II and the "high cost of living," as it was called at the time. A big part of keeping prices affordable during the Second World War was not only mandatory rationing (it was voluntary in WWI), but also the Office of Price Administration (OPA) was able to freeze or set prices nationally for all consumer goods. Agricultural commodities were exempted from OPA control. Although the OPA was founded in 1941, it wasn't until 1943 that it settled on direct price control as the most effective means of regulation of consumer prices (The Oregon State Archives has a great overview of the OPA and price controls as part of an online exhibit on WWII). Although direct price control - "ceiling prices" they were called at the time - were extremely popular with the general public, retailers and especially manufacturers were constantly looking for ways around the regulations or to weaken them. The OPA used peer pressure and enlisted an army of housewives to report on those not adhering to regulations. This propaganda poster, one of many produced by the OPA, features a well-coiffed housewife holding a can of what appear to be tomatoes (or maybe cherries) smiling at a balding grocer, who in turn points rather wryly to a posted placard reading "OPA Price Ceiling List." The text of the poster read "Let's TEAM UP to keep food prices down for the sake of America's Future." Ceiling prices were published by the OPA and required to be posted in retail spaces, especially food, which was among the most price-controlled area of American life. Although small businesses could charge slightly higher prices than regional chains, the prices often differed by only a few cents, and were designed to help out the small businesses by giving them slightly higher profit margins. Much of the propaganda around price control and rationing both calls for cooperation between retailers and consumers, and this poster is no exception. Retailers were expected to follow regulations and consumers were expected to only patronize retailers who were following the rules. That didn't stop a huge black market from developing, especially around meat. Despite massive quantities of meat being used to feed the armed forces and sent overseas to support the Allies, ranchers and meatpackers were unhappy with price controls and in the aftermath of the war some actively withheld meat from the market in an effort to create false scarcity and anger voters, who would oppose the price controls. By the fall of 1946, meat production had fallen by 80%. Angry voters blamed the party in power - the Democrats - rather than the ranchers and packers who were colluding to manipulate the market, and delivered a Republican win in the election of 1946 - the first since 1930. The tension between food producers and food consumers has a long history. In the "free" market, farmers and ranchers are rewarded for low yields and production because prices go up. Getting producers to produce enough to feed people affordably while still ensuring they make a fair profit is a dilemma that plagued the early 20th century. Finally, during FDR's New Deal, government funds were used to subsidize farmers through low-interest farm loans and also direct payments to steady the supply on the market and protect farmland from the Dust Bowl. These were revoked in the 1970s under Nixon's Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz of "get big or get out" fame. Instead, the government maintained an agricultural price floor - if the market price fell below the floor, the government would make up the difference to the farmer. So what happened? Of course prices instantly fell below the floor - because they could. Food manufacturers benefitted from purchasing commodity crops for less than they cost to produce, our modern processed food production flourished (to the detriment of our health), and taxpayers footed the bill. In the modern era, many economists (including at NPR) have used the jump in post-war inflation as the OPA was dissolved wholesale (instead of gradually increasing prices as economists of the period recommended) as proof that the OPA was always a bad idea, doomed to failure. But the people who hated the OPA the most seemed to be the people who stood to profit the most from inflation - the manufacturers, packers, and retailers who could pad their bottom lines with price increases in the name of "scarcity." Sound familiar? It seems to me as though the OPA, behemoth bureaucracy though it was, was more the victim of those determined to see if fail, at all costs, than a violation of the "natural order." Because although economists like to talk about scarcity driving up prices, they have very little to say about price increases that are not caused by scarcity, and even less to say about price increases on goods that people cannot afford to do without - like food and housing and healthcare. The tension between pro-business forces who oppose regulation and pro-consumer forces who support regulation date back to the 19th century in the United States. The conflict was present in the fallout from the Panic (and subsequent 7 year Depression) of 1893, in the industrial recessions of the early 20th century, and especially in the handling of the Crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression. FDR's New Deal and a dramatic increase in government regulation of business and the economy helped pull us out of the Depression (wartime defense spending didn't hurt either). But the OPA caused a strong negative reaction among the pro-business, anti-regulation groups that shifted politics back toward the myth of the "free" market. But while inflation did increase by as much as 20% after the OPA was dissolved, strong postwar wages helped mitigate the effects. Whereas wages in the modern era have largely stagnated for over a decade, especially for workers on the lower end of the economic spectrum. A few economists have discussed the morality of price gouging, but should we rely on the morals of businesses in a capitalist society? The tensions between pro- and anti-regulation forces are still at play in modern politics. After decades of deregulation, the Biden Administration has begun re-regulating or executing new orders on the environment, consumer protections, and immigration, but has yet to address the modern "high cost of living," although it is trying to reduce meat monopolies. But corporate consolidation has continued unchecked for decades, belying the "free market" and hurting consumers. It's a problem that won't be solved overnight. As prices for housing, food, healthcare, and other essential goods continue to rise, will we return to the lessons of the Office of Price Administration? That remains to be seen. I, for one, wouldn't mind a return to the "fair price" lists published in WWI. If politicians can't stomach a return to government regulations, maybe we can at least shame food corporations into sacrificing some of their record profits to ensure Americans have enough to eat. What do you think? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

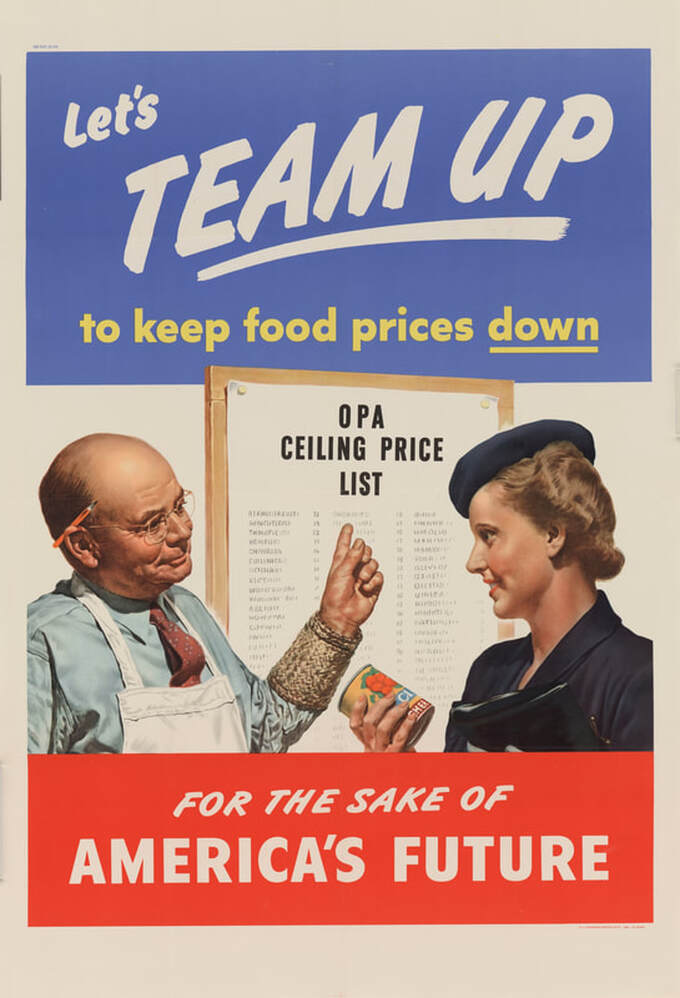

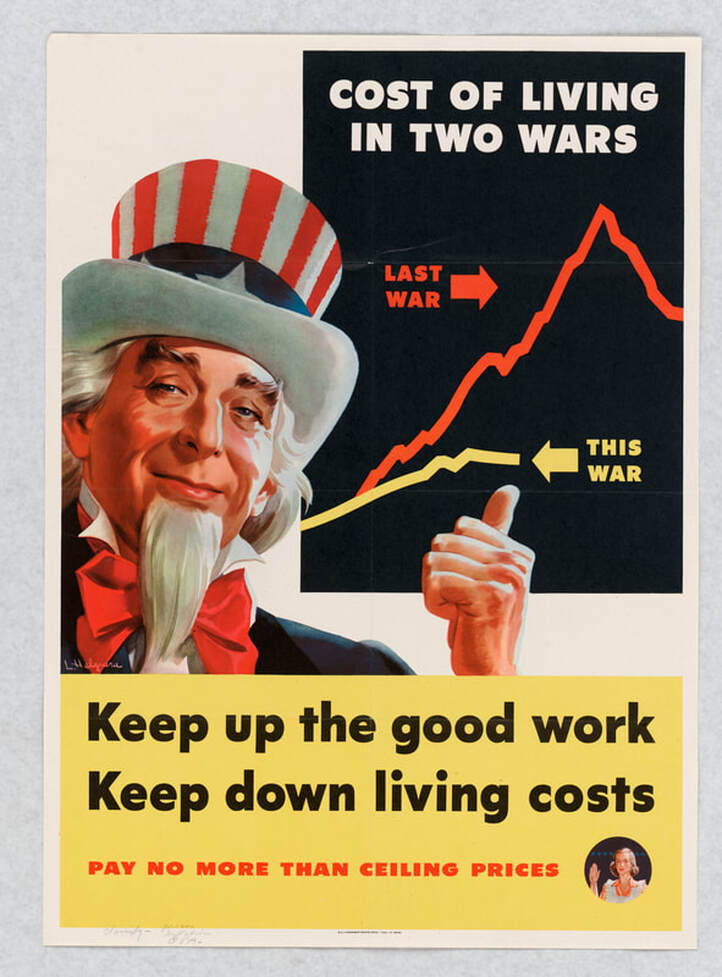

Last week we talked about the High Cost of Living in the First World War. Those memories were close at hand during the Second World War. During World War I, the federal government did little to control prices at the consumer level, and rationing was voluntary. The U.S. Food Administration did control whether or not retail establishments and manufacturers complied with rationing and other rules through a complicated system of licensing and oversight, but individual consumers were technically allowed to make their own food choices. During World War II, things were different. Rationing was mandatory, even if the stamps were often confusing, and black markets definitely existed. But the creation of the Office of Price Administration froze the official prices of a whole host of goods, including food, to try to offset wartime inflation. Once again retailers were being regulated by the government, but this time the OPA relied on consumers to help report violators. By enlisting housewives to help enforce "ceiling prices" by refusing to purchase goods at that exceeded the published price lists, the OPA got a free labor source, and the housewives ensured that their retailers were not cheating them. Black women, in particular, benefitted from this practice, as discrimination meant they were subject to being cheated.  "Here's a war job all America may be proud of. The rise in wartime cost of living today is less than half the World War I increase... only the patriotic cooperation of the public and businessmen with the government's price control program made this record possible... let's keep up the good work by keeping the Home Front Pledge: "I pay no more than ceiling prices... I pay my ration points in full."" Office of Price Administration, National Archives. This pair of posters, comparing the inflation of food from WWI to WWII, was designed to prove the effectiveness of the Office of Price Administration and its price control efforts. In the first one, Uncle Sam points to a chart that compares the rise of inflation over the course of both World Wars. In the second, two bar charts on inflation are compared. In the first, labeled 1918, a (suspiciously-1930s-attired) housewife tries and fails to reach a basket of food labeled "Cost of Living" as it rises on a bar chart of 64.6% inflation. Whereas the 1944 housewife can easily reach her basket at 25.9% inflation. Interestingly, her bar chart has a white line 3/4 of the way up which reads "Price control began here." The black bar below reads "Before Price Control," implying that inflation could have been much worse without the intervention of the OPA. Both statistics are attributed to the 53rd month of the war, which seems to indicate that the inflation statistics for World War I start in 1914, not 1917, when the U.S. officially joined the war, which tracks with the cost of living increases that began long before April 7, 1917. These two posters indicate just one of the ways in which the lessons of the First World War were applied to the Second. Some lessons, however, remained hard to swallow. During WWI, the United States Food Administration, although formed by executive order in May of 1917, received no funding from Congress until August, 1917, because a number of congressmen objected to the sweeping powers and controls it gave the executive branch. In an effort to avoid a bloated post-war bureaucracy, it was quickly dismantled in early 1919, despite the fact that the cost of living rose precipitously after the war. Similar sentiments about the power of the Office of Price Administration were debated during WWII, and numerous attempts by organized retail and manufacturing organizations to weaken it started as early as 1944. The OPA was allowed to temporarily expire in 1945, and prices jumped almost instantly. It was hastily reinstated, but in a weaker form, and was fully abolished in 1947. Some price control functions for sugar, rice, and a few other products were shifted to other agencies. In her article, "'How About Some Meat?': The Office of Price Administration, Consumption Politics, and State Building from the Bottom Up, 1941-1946," historian Meg Jacobs talks about how the Office of Price Administration helped Americans determine that high standards and low cost of living was their reward, nay birthright, for surviving two World Wars and a Great Depression. Caught between empowered consumers and producers and retailers anxious to throw off the yoke of government regulation, the OPA was at the center of post-war discussions about the future of the American economy. Given today's cost of living problems, I find it fascinating to study the economics of the first half of the 20th century, and how societal reactions and government policies continue to shape today's discussions about the future of our economy - whether people realize it or not. Today, economists are studying the impact of the Great Recession and COVID-19 on our economic future, just like historians and economists in the 1920s and 1940s did when they were looking back at the two World Wars. Further Reading

If you enjoyed this blog post, consider supporting The Food Historian on Patreon! Patrons get special perks, including members-only content, access to digitized cookbooks, and occasional snail mail. Patrons also help keep this blog free for everyone. Join today! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed